Auction: 24003 - Orders, Decorations and Medals

Lot: 124

'What happened when the shells struck a ship and that dull red glow appeared? Was everyone immediately asphyxiated, burnt or mangled? In another half hour would I be alive and unhurt, or would I be lying half-charred with the inside of me hanging in bits on the deck? I suddenly thought of an old instructor at Osborne who used to curdle our youthful blood with accounts of some of the nasty sights that he was alleged to have seen during the bombardment of Alexandria. That, luckily, made me smile. I felt very empty inside as though I hadn't had a meal for ages though I didn't feel hungry. My tongue was dry, and I smoked a cigarette hard, hoping that with its aid, an illusion of sang-froid and devil-may-carishness was accepted by my neighbours at its spurious value … '

Lieutenant D. Wainwright, A.M., R.N., of H.M.S. Nomad, contemplates a grim ending at Jutland.

A notable Great War and Second World War campaign group of seven awarded to Lieutenant-Commander J. E. Bellingham, Royal Navy, who was present at Jutland as a 'Gunner, R.N.' in the destroyer H.M.S. Nomad

Famously, in direct support of her consort Nestor - Commander Barry Bingham, V.C. - Nomad was deluged in enemy shellfire and sunk with a loss of eight killed and four wounded: plucked from the North Sea by the Germans, Bellingham proved to be a reluctant guest of the Kaiser, being commended for his escape work in a camp at Brandenburg

1914-15 Star (Gnr. J. E. Bellingham, R.N.); British War and Victory Medals (Gnr. J. E. Bellingham, R.N.); 1939-45 Star; France and Germany Star; Defence and War Medals 1939-45, generally very fine or better (3)

James Ernest Bellingham was born at Kenmare in Co. Kerry, Ireland on 2 March 1883 and joined the Royal Navy as a Boy 2nd Class in June 1902. Clearly a talented hand, he attained Petty Officer status in September 1906 and, having passed the relevant examinations, was appointed a Gunner (T.) in January 1913.

By the outbreak of hostilities in August1914, Bellingham was serving in the destroyer H.M.S. Tigress and, having been present in her at the battle of Dogger Bank in January 1915, he removed to another destroyer, the Nomad, in March 1916. Of Nomad's subsequent gallant part in the battle of Jutland, much has been written, including an account left by her gunnery officer, well-known to Bellingham, namely Lieutenant D. Wainwright, A.M., R.N.:

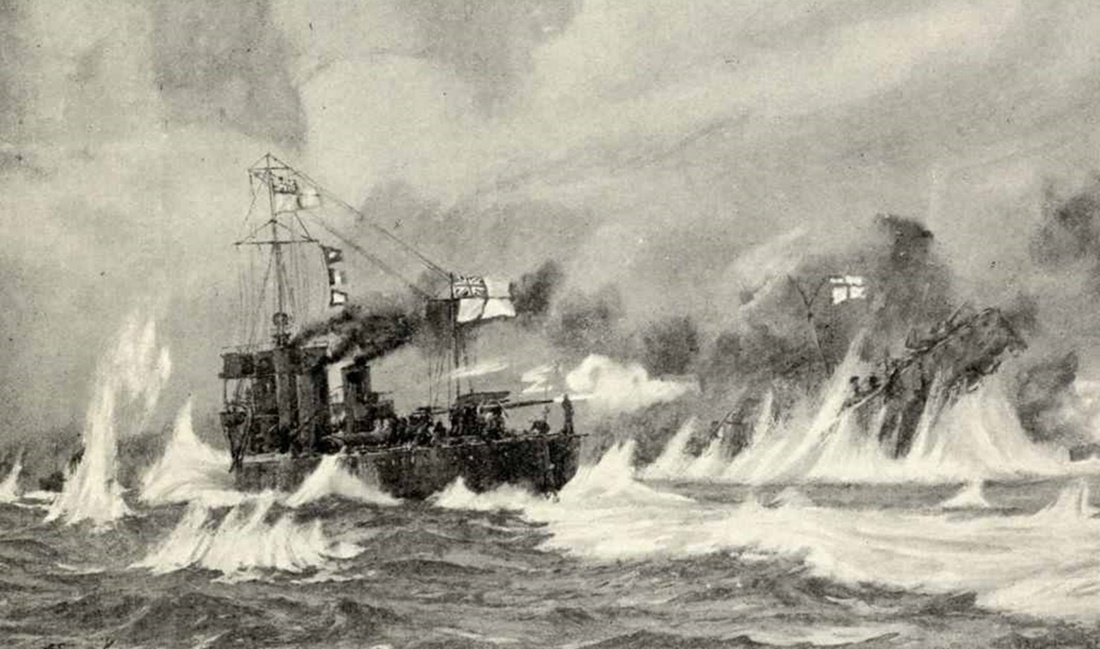

' … We were going nearly thirty-five knots and the whole ship vibrated with the strain. H.M.S. Nestor led us, then ourselves, then H.M.S. Nicator, but the latter going better than we did eventually took second place astern of Nestor. Simultaneously the German Destroyers moved out towards us, and we opened fire on each other. The din was ghastly. We were going all out, the ship shivering with speed; our three four-inch, one on the foc'sle, one aft and one amidships were all firing; the German Destroyers' shells were exploding round us, the projectiles from the big ships whistling overhead and the perpetual thunder of their guns rolling eternally. Control of our three guns from the bridge became a farce, what with the fact that our ever-changing course and the movement of the German Destroyers meant that each gun's target was continually shifting. The order for "Local Control" was given, which meant that No. 1 took charge aft, the gunner [Bellingham] took the midship gun and I went down to the foc'sle.

Events moved too quickly to get other than fleeting impressions. I remember ceasing fire on a Destroyer in the belief that she was a friend, then the smoke cleared, and we saw her colours plainly and got at her again until she started sinking. Every time we altered course the ship heeled over, but gradually I noticed that we seemed to be permanently listing to port. The German Destroyers had retired, and both the fleets had turned about to the North-North-West. We seemed to be moving very slowly, and gradually we stopped and the list to port increased.

Looking aft I saw clouds of steam amidships and going there found the deck a shambles. A shell had struck the starboard side, entered the engine room and severed the main steam pipe, effectively stopping our motive power. We had fired two of our torpedoes, one was left in a third tube with a merry little fire on the deck underneath it which was soon put out and the fourth tube was out of action. A shell had struck just by it and blown the man, whose job it was to sit astride the tube, clean over the side. The bilge pumps were out of action, we were leaking badly and only two men were alive in the engine room. This was our position at about 4.30 p.m.'

Generous offers of a tow from Nicator were declined, and preparations for the inevitable end sped up. Wainwright continues:

' … When a ship is in danger of sinking or capture by the enemy all confidential books and documents must be destroyed, and I spent five minutes in the chart room routing out signal books, cyphers and charts and dumping them over the side. Meanwhile all boats were lowered to the deck level and rafts were cast loose. We still had one torpedo left, but in order to train the tube on the leading enemy ship it would have been necessary to turn. As we couldn't do this we had perforce to wait until the target ship came into line of sight instead.

Just then the three leading battleships opened fire on us. The rough idea of fire control by spotting corrections is this. If the first round fired lands well over the target, then the sights are lowered say 800 yards. The next shot is probably short and then the order of "Up 400" is given. If this is over "Down 200," and so on, always correcting half the amount until the target is hit. Similarly, the deflection is corrected for directional errors by giving orders "Right 20", "Left 10", "Right 5", etc. until direction is correct. With a sitting target a hit should be obtained after very few spotting corrections have been given. Like everyone else in the Navy I have many times watched from a ship the effect of spotting corrections on gunfire, but never previously had I watched from the target!

Our foc'scle gun would not bear and the rest were out of action, so we waited. No. 1 and I stood on the foc'scle. Between us and the enemy was a piece of painted canvas, and its moral support was enormous. "What the eye don't see, the heart doesn't grieve about," was our motto then. The first salvoes passed over us. "Down 800", said No. 1, laconically. The next were short - "Up 400," said I, and so we kept this farce up until "Next one," said I. By the grace of a bit of dust that must have got in some Hun's eye the next salvo was wrong for direction, though the range was right. "Damned rotten shooting,", said No 1. We went aft and watched the last torpedo fired but alas it missed.

At this moment they got our range, and things began to happen. As we sank lower the order "Abandon Ship" was given. The whaler and motorboat were miraculously unhurt and dead ahead of the sinking ship. The dingy was splintered but looked as if it would float. I was sent forward and the skipper went aft to see that no-one wounded was left on deck. The stern was now under water and the whole hull was an inferno of smoke, steam, explosions, and hailstorms of splintered metal. The skipper returned staggering and badly wounded, but we got into the dinghy and pulled clear. She had lain alongside with nine men in her waiting quite uncomplainingly for the captain to return. Suddenly we saw two wild figures on deck. We went back and took them in the dinghy, two stokers both scalded and half raving with their agony. They must have been knocked out and missed the order to abandon ship.

Only the fore half of Nomad was afloat now but the ensign still flew at the masthead. All this time the dinghy had been making water steadily and now she gracefully sank under, and we swam away. One by one we were picked up by the motorboat and as I was hauled over the side I turned and saw Nomad take her final dive. The Germans put a few parting salvoes into the middle of the survivors in the water and then disappeared into the northwest leaving two Torpedo boats to collect us as prisoners … '

As stated, Bellingham proved to be a reluctant prisoner, his service record noting that he was recommended by Captain C. V. Fox, Scots Guards, 'on his escape from Brandenburg … good work done there.' Alas, although Bellingham made the Dutch border, he had to wait until November 1918 to be repatriated.

Fox, a well-known pre-war rower, got home earlier, and provided evidence of an atrocity at Brandenburg camp, when a fellow internee was burnt to death because the guards would not let him escape a burning building.

Later career

Promoted to Lieutenant in February 1931, Bellingham was placed on the Retired List in March 1933. Having then been advanced to Lieutenant-Commander (Retired) in February 1939, he was recalled on the renewal of hostilities and appointed Local Naval Officer (L.N.O.) at Yealm in South Devon. And a stint of duty on the Staff of the C.-in-C. Plymouth in 1940-41 aside, he appears to have remained employed as an L.N.O. for the duration of the war, but, from late 1941, as a Lieutenant in the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve.

He died at Newton Ferrers in September 1963, aged 80; sold together with copied ship photographs and research.

For the medals awarded to his son see lot: 129.

Subject to 20% VAT on Buyer’s Premium. For more information please view Terms and Conditions for Buyers.

Sold for

£580

Starting price

£240