Auction: 24002 - Orders, Decorations and Medals

Lot: 123

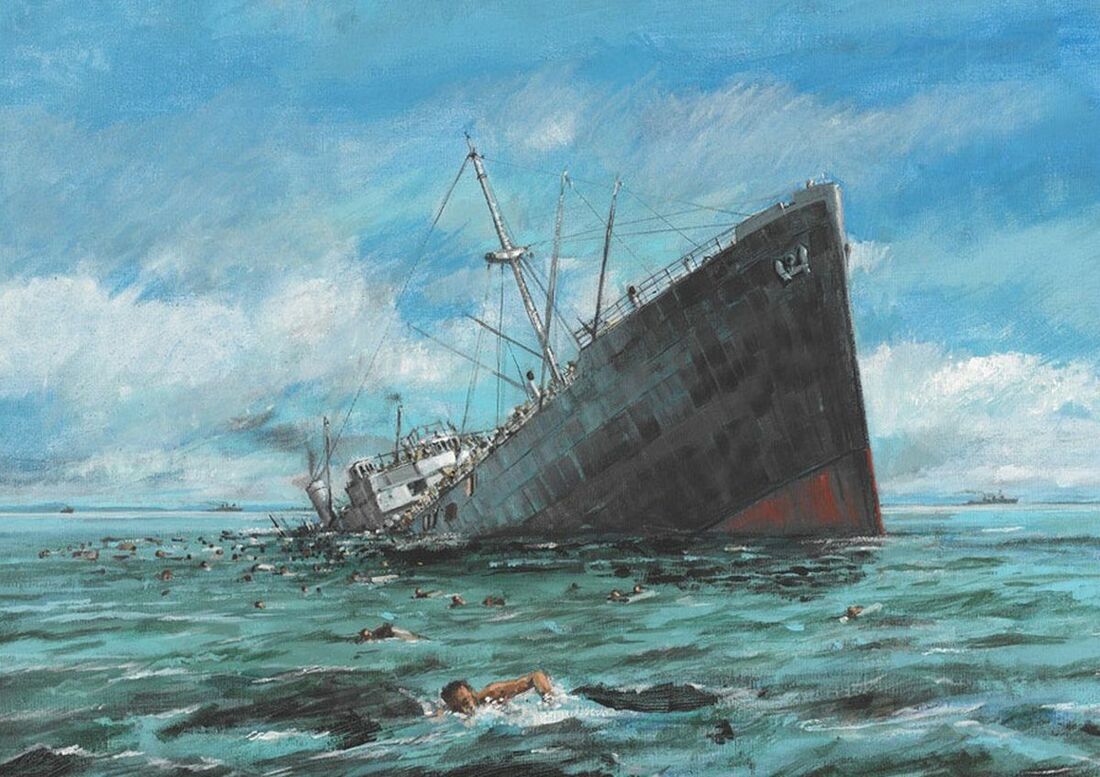

'It was pleasant on deck in the sunshine of a bright October day. Some men sat quietly down in the bows of the ship and discussed what they should do next. Some produced rare cigarettes.

About five miles to the west were some islands; this looked like a long swim for men in poor condition. Moreover, a large proportion of the men had no life belts. Major Walker, Second-in-Command of the Royal Scots, gave his life belt to a non swimmer and was not seen again.'

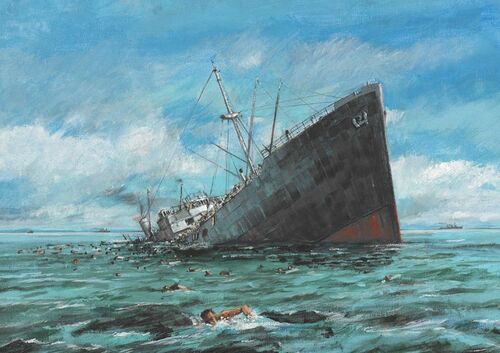

The Sinking of the Lisbon Maru by G. C. Hamilton, refers

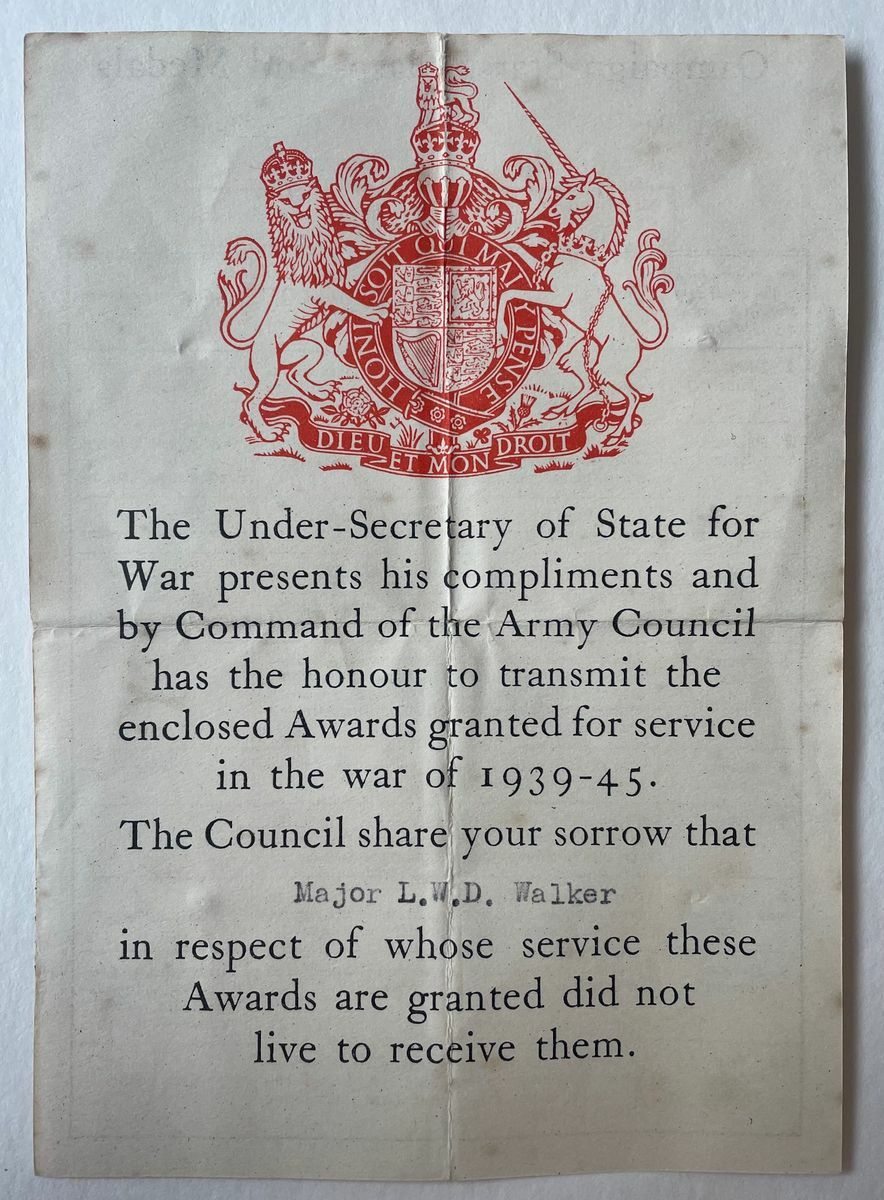

The poignant campaign group of four awarded to Major L. W. D. Walker, 2nd Battalion, Royal Scots, who was wounded in action during the Fall of Hong Kong and taken a Prisoner of War, he lost his life in captivity on 2 October 1942 after the Japanese cargo liner Lisbon Maru was torpedoed and sunk, along with over 1,800 other Prisoners of War - he was the Senior Officer of his Regiment on board that famous day

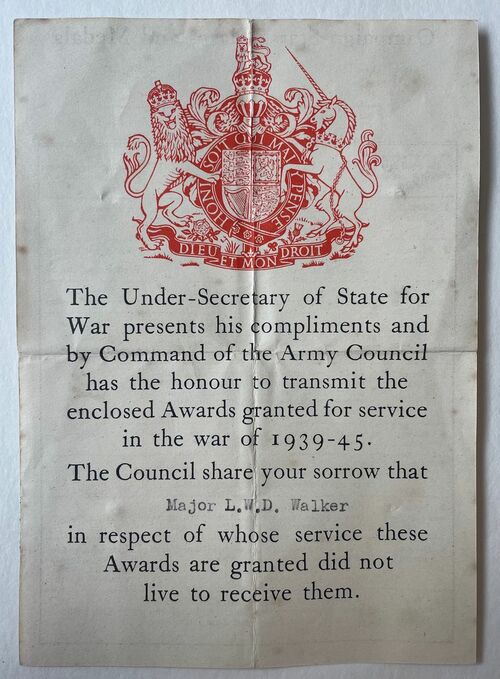

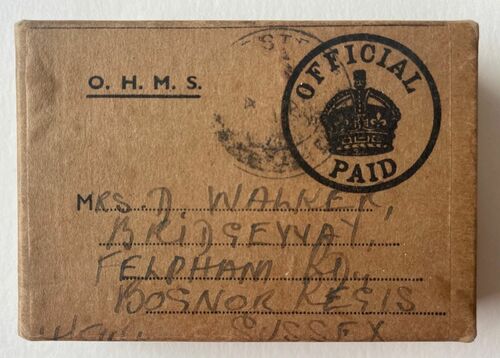

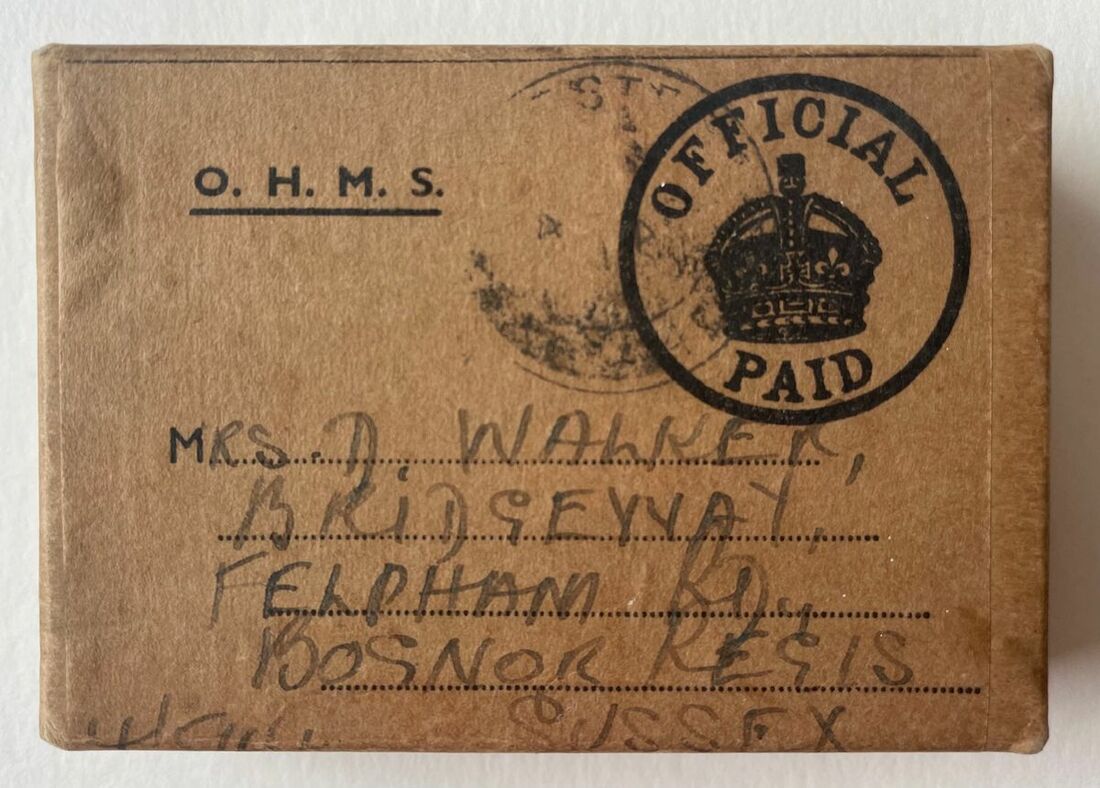

1939-45 Star; Pacific Star; Defence and War Medals 1939-45, in their waxed envelopes of issue, with Army Council Condolence slip in the name of 'Major L. W. D. Walker', confirming '4' Medals and postage box named to 'Mrs D. Walker, Bridgeway, Felpham Rd., Bognor Regis, Sussex', extremely fine (4)

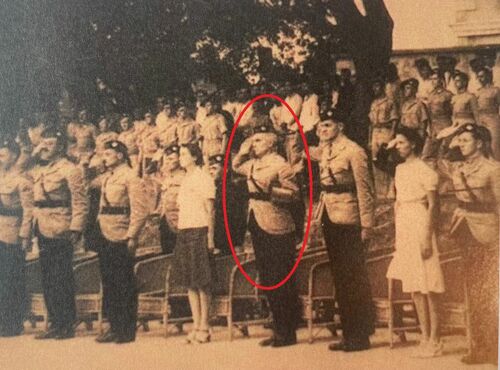

Leighton William David Walker was born on 1 April 1901, the son of The Rev. William W. Walker and Mary. Commissioned 2nd Lieutenant on 24 December 1920, by the outbreak of the Second World War he was with the 2nd Battalion, Royal Scots. The unit were out in Hong Kong and Walker was photographed with his brother Officers taking the salute at a Beating Retreat in September 1941. He had married Dora, who was living in Bognor Regis.

Little did they know the unit would be thrown into the Battle of Hong Kong soon after. Walker and his comrades put up a fine performance in spite of the dreadful odds against then - he being wounded in the stomach and thigh on 22 December 1941 - but were captured and taken prisoner of war at the Fall of Hong Kong on Christmas Day 1941. By 26 September 1942 his Regiment was transferred from the Shamshuipo Camp, Hong Kong.

Lisbon Maru - Hellship

The Lisbon Maru sailed from Hong Kong on 27 September 1942, bound for Shanghai and labour camps on the Japanese coast. She was armed, and carried 1,816 British Prisoners of War, 778 Japanese troops and a further guard of 25 men for the prisoners. There was nothing that identified her cargo as Prisoners of War.

379 Royal Navy personnel were accommodated in No. 1 Hold at the front of the ship. A further 1,077 troops were crammed into No. 2 Hold, forward of the bridge, including the Senior British Officer on board, Lieutenant-Colonel H. W. M. Stewart, Commanding Officer of the 1st Battalion, Middlesex Regiment, whilst 380 men of the Royal Artillery were placed in the stern. Conditions were appalling, made worse by a lack of sanitation and the sea conditions. At the base of No. 2 Hold, Dennis Morley, a 22-year-old Private in the Royal Scots Regiment, later recalled being 'showered by the diarrhoea of sick soldiers above him…swimming in excreta, virtually.'

On 1 October 1942, the American submarine Grouper fired six torpedoes at the Lisbon Maru off Dongfushan in the Zhoushan Archipelago, to the south of Shanghai. Five of the unreliable Mark 14 'fish' either passed under the target or failed to detonate, but one exploded against the stern bringing the ship to a standstill. Grouper immediately came under retaliatory attack from enemy patrol boats and aircraft and departed the scene, enabling the Japanese troops aboard the Lisbon Maru to be taken off the stricken vessel. As they departed, they battened down the hatches, leaving their prisoners standing in the dark and running short of air to breathe.

Throughout the following night the prisoners remained trapped in the holds. Messages in morse code were rapped on the bulkheads between them, and gradually the stern began to fill with water. Something urgently needed to be done to prevent the men drowning or dying of asphyxiation. As the sun began to rise on the morning of 2 October 1942, the men felt the hull give 'a sudden drunken lurch', and a frantic escape effort began. Morley describes the scenes that he witnessed:

'Well, one chap, he was in the Middlesex Regiment, he was a butcher and the Japanese allowed him this knife, which he was able to put through the planks. He got through to the canvas, eventually - the whole lot. The canvas could be lifted out of the way and the planks moved which is how we got out.

A bit of panic started because everyone was trying to rush up to this ladder and everybody was fighting to get onto this ladder. Consequently, you're getting so far up and falling down into the bottom of this hold - until this officer, Captain Cuthbertson of the Royal Scots, stopped the panic and got them to quieten down.'

This account is challenged by another which states that Lieutenant Howell managed to cut his way out of the hold using a bread knife smuggled aboard ship, but whatever the case, the first P.O.W.s to reach the deck were fired at by a few remaining Japanese guards who were quickly dispatched. Then the British began to slide off the side of the ship into the water in an attempt to get away from the vessel, but they were targeted by machine-guns from the Japanese who were watching on.

It was only when Chinese fishermen started coming to the aid of the soldiers and sailors in the water that the firing ceased and the Japanese began to gather them up as well. At the stern of the ship, men of the Royal Artillery continued to hoist themselves up a ladder which eventually broke; in one of the most harrowing scenes of the tragedy, the survivors in the water listened with horror as dozens of trapped men of the Royal Artillery went down with the ship singing 'It's a long way to Tipperary'.

In total, 828 Prisoners of War died either aboard ship or in the waters around the vessel (The Sinking of the Lisbon Maru, Britain's Forgotten Wartime Tragedy, refers). Especially tragic was the fact that the ship had been sunk by an American submarine, whose crew were completely unaware that there were Allies aboard until they picked up a radio signal several days later. Of the survivors, only 748 returned to the U.K. alive following the cessation of hostilities.

As stated above, Walker gave up his own life vest to a comrade who couldn't swim and slipped below the waves. He has no known grave and is commemorated on the Sai Wan Memorial, Hong Kong.

Subject to 20% VAT on Buyer’s Premium. For more information please view Terms and Conditions for Buyers.

Sold for

£450

Starting price

£320