Auction: 22002 - Orders, Decorations and Medals

Lot: 189

(x) A Great War ‘Caspian Sea’ D.S.M. group of four awarded to Able Seaman H. G. Clark, Royal Navy

Distinguished Service Medal, G.V.R. (J.11321 H. G. Clark. A.B. Caspian Sea 1918-1919); 1914-15 Star (J.11321 H. G. Clark. A.B. R.N.); British War and Victory Medals (J.11321 H. G. Clark. A.B. R.N.), together with his identity disc, very fine (4)

D.S.M. London Gazette 11 November 1919:

‘The following awards have been approved for services in the Caspian Sea 1918, 1919.’

Recommendation states:

'Venture Caspian Sea 1918-19. Brought to notice for the work done on behalf of the expedition.'

Harry George Clark was born at Leyton, Essex, on 18 May 1895, and worked as a gardener. He joined the Royal Navy as a Boy 2nd Class on 31 January 1911 and trained in the Impregnable at Devonport. Having been advanced Boy 1st Class on 15 September, he joined the armoured cruiser Leviathan for service with the Home Fleet. Clark's home depot was Pembroke, the RN barracks at Chatham, and he returned there between his drafts at sea. He was posted to Pembroke on 15 January 1912; two weeks later he joined the battleship Duncan. He was rated as Ordinary Seaman on his eighteenth birthday in 1913, and enlisted for twelve years' service. When he joined her, Duncan was part of the Mediterranean Fleet; in 1913 she was transferred to the 6th Battle Squadron at Portsmouth, where she was employed for gunnery training.

On 16 September 1913 Clark was drafted to the Lancaster, a Monmouth-class armoured cruiser which was recommissioned from the reserve. She was assigned to the 4th Cruiser Squadron on the North America and West Indies station, and she sailed for Bermuda a week or two afterwards. Over the following months she visited the British colonies in the Caribbean - St Kitts, Antigua, Barbados, Jamaica and Belize - and also Martinique and Haiti.

Mexico was in a state of serious unrest in 1914 with revolutions and coups d'etat. In April there was a confrontation between the Mexicans and the Americans, known as the Tampico Affair, and on 21 April US Marines and sailors seized control of the port of Vera Cruz. This provoked attacks on Americans in other parts of Mexico. Lancaster arrived at the port on the 24th; two days later she left for the nearby city of Coatzacoalcos, where she remained until 9 May. Her Log records the arrival of American refugees, including a train with 380 from Mexico City; some were taken aboard for a few days. A Mexican General was honoured with an eleven-gun salute. The cruiser then proceeded back to Vera Cruz and Tampico before returning to Bermuda.

Lancaster was still at Bermuda when War was declared on 4 August. A few days later she made a passage to St Johns, Newfoundland, and then carried out patrols off New York and in the western Atlantic, searching for German raiders. In mid-January 1915 she sailed for Plymouth, where she arrived on the 30th; she proceeded first to Queenstown, Ireland, then to Scapa Flow and Cromarty, from where she carried out patrols in the North Sea. She docked at Chatham in July 1915 and Clark (who had been rated Able Seaman on 1 October 1914) left the ship on 30 July. He was drafted to Pembroke and gained his qualification as a seaman gunner.

King Edward VII

In November 1915 Clark joined the ship's company of King Edward VII, flagship of the 3rd Battle Squadron. She was the name-ship of a class of eight, and had been laid down at Devonport in 1902, launched on 23 July 1903, and completed in 1905. She measured 425 feet long and had a displacement of 16,350 tons. As with all pre-Dreadnoughts she had a mixed armament, including four 12-inch guns, four 9.2 inch guns and ten 6-inch guns. She had a speed of eighteen and a half knots, and her complement numbered 777. She and her sisters were looked upon as being perfectly proportioned:

'The height of masts and funnels and their relative positions…were all calculated carefully to give an ensemble of balance and symmetry unique among the profiles of armoured ships.' (Parkes, British Battleships, refers)

On the outbreak of the Great War the 3rd Battle Squadron formed part of the Grand Fleet at Scapa Flow. The presence of the "Wobbly Eight", as they were known, greatly complicated the deployment of the Grand Fleet as their speed was three knots less than that of the rest of the Fleet. When the Fleet carried out sweeps, she and her sisters often steamed at the heads of divisions of the more valuable dreadnoughts where they could protect the latter by watching for mines - or by being the first to strike them. In November 1914, in response to German attacks on the east coast of the United Kingdom, they were transferred to Portland, where they would be better placed to respond to German raids or an invasion attempt. The 3rd Battle Squadron put to sea several times over 1914 and 1915 in response to German raids but on each occasion failed to make contact with the enemy. In fact, the "Wobbly Eight" had the sad distinction of never once having the opportunity of firing at the enemy throughout the war. Battleships from the squadron were sometimes deployed off Scotland to support the Northern Patrol.

On 16 January 1916 King Edward VII was on passage from Rosyth to Belfast for dockyard maintenance. At 07.00hrs, when off Cape Wrath at the northern tip of Scotland, she struck a mine, part of a very scattered field laid by the surface raider Möwe. The explosion occurred under the starboard engine room, and King Edward VII listed to starboard. There were no casualties. She was taken in tow but she settled deeper in the water and in a rising sea and strong winds she proved unmanageable. With darkness coming on, Captain Maclachlan ordered 'Abandon Ship'; he was the last man off, transferring to a destroyer at 16:10hrs. The King Edwards were remarkably stable ships and even after being abandoned she remained afloat for another four hours before capsizing.

Royal Oak

King Edward VII's company remained intact and on 1 May 1916 it was transferred to the Royal Oak at the beginning of her maiden commission. She was one of the five Revenge class battleships ordered under the 1913 Programme. She was constructed at Devonport Dockyard; laid down in January 1914, launched on 17 November 1915 and completed in May 1916. She had a standard displacement of 27,500 tons, a speed of 22 knots and a main armament of eight 15-inch guns and fourteen 6-inch guns. Her wartime complement was 997. There were only three boiler rooms which made it possible to combine their uptakes into one large funnel, giving the class a most distinctive and impressive profile. Royal Oak was assigned to the 4th Battle Squadron of the Grand Fleet at Scapa Flow. This squadron also included the fleet flagship, Iron Duke.

Royal Oak joined the fleet just in time to take part in the Battle of Jutland on 31 May. When the Battle Fleet deployed into one long line, she was fourteenth in line, immediately astern of Iron Duke. As the fleet deployed, it passed by the crippled light cruiser Wiesbaden and many of the battleships fired at her - it is estimated that between 18.20-45hrs at least 300 large calibre shells were expended on her, but only about ten hit and none caused fatal damage. At 18.29hrs Royal Oak fired five salvos at the hapless vessel and claimed one hit. Seven minutes later more suitable targets were observed and Royal Oak opened fire on the German battleships. Jellicoe succeeded in the classic manoeuvre of 'crossing the enemy's T' and nearly all the British ships were able to fire on the enemy, whilst the Germans could bring only a few of their guns to bear. None of the British ships were hit although Royal Oak was straddled at 18.33hrs. After being battered for about ten minutes the Germans skillfully executed a simultaneous 180 degree turn away and vanished into the mist. However, for reasons which have never been adequately explained, at 18.55hrs Scheer ordered another turn and led his fleet back towards the Grand Fleet. Within minutes, fire from the whole of the British line was sweeping the length of the German line at ranges of 10,000-14,000 yards. Under this torrent of heavy shells the German fleet faced imminent destruction. Scheer ordered his battleships to execute another battle turn away, covered by the battlecruisers and destroyers which charged the Grand Fleet.

At 19.15hrs Royal Oak observed three battlecruisers on her starboard beam and fired on one of them, the Derfflinger. Two of the shells struck her funnel and passed through without exploding. The target was then lost in the mist. Royal Oak shifted her fire to Seydlitz and at 19.27hrs one of her 15-inch shells hit one of the battlecruiser's guns, about eight feet from the turret. The gun was badly flattened and thrown violently to one side, distorting the cradle. The whole turret turning gear was disabled and there was significant splinter damage to a nearby rangefinder and a 5.9-inch gun. Fourteen enemy destroyers then charged the fleet at thirty knots; one flotilla managed to come within 8,000 meters and discharged a total of thirty-one torpedoes. They were met with a wall of fire from the 4-inch and 6-inch secondary batteries of the battleships - Royal Oak fired eighty rounds of her 6-inch ammunition. One destroyer was sunk and a number of others damaged but they achieved Scheer's purpose by forcing the cautious Jellicoe to turn the fleet away from the fleeing Germans rather than pursuing them. As night fell the Grand Fleet did not succeed in re-establishing contact and the German fleet was saved from annihilation. Royal Oak fired thirty-eight of her 15-inch shells. Although straddled by shellfire on one occasion, she was not hit herself and suffered no casualties. After the battle she was reassigned to the First Battle Squadron.

It appears that Clark then volunteered for the submarine service, for on 13 December 1916, only six months after joining the Royal Oak, he was transferred to Dolphin, the submarine training school at Gosport. However, he lasted only five days there and there is a note "medically unfit" on his record, indicating that he probably suffered from claustrophobia or some other condition which rendered him unfit for service in "the Trade". Clark returned to Pembroke. He was promoted Leading Seaman and had further training, qualifying as a gun-layer 2nd class in April 1917.

Clark returned to active service in June 1917 with a draft to Europa, a destroyer depot ship based in Mudros near the Gallipoli peninsular. This was soon followed by a transfer to Europa II, the depot ship for monitors. These were shallow-draft vessels equipped with heavy guns, deployed in shallow coastal water for bombardment of targets ashore. From August 1917-February 1919 he was assigned to the M22, a ship of 540 tons with a complement of sixty-nine officers and men. She was armed with one 9.2-inch gun (from the old cruiser Gibraltar), one 12-pounder and one 6-pounder anti-aircraft gun. She was deployed in the eastern Mediterranean and supported the operations in Egypt and Palestine. Clark committed some misdemeanour and in May 1918 was disrated to Able Seaman. On 2 February 1919 Clark was drafted to the depot ship Theseus II at Batum, on the eastern shore of the Black Sea. He then volunteered to join the small RN detachment in the Caspian Sea.

Caspian Sea Campaign - D.S.M.

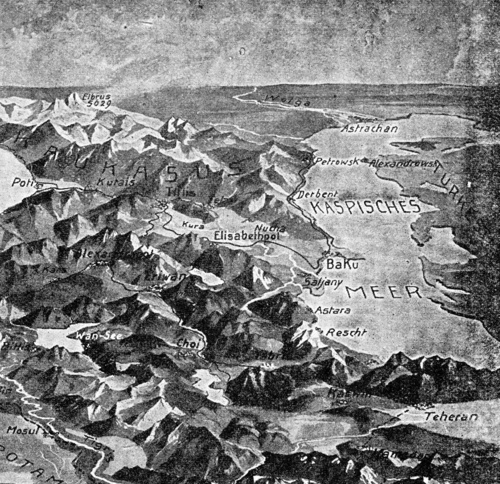

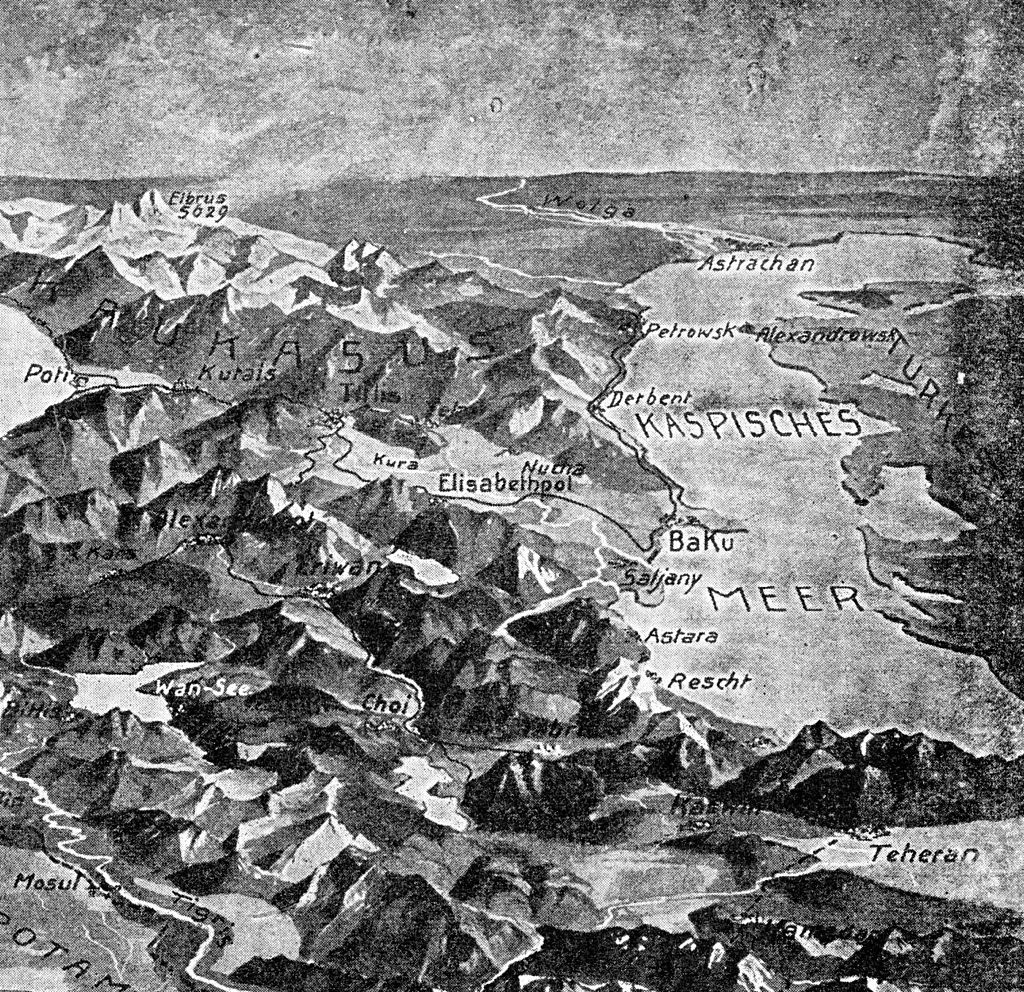

The Caspian Sea measures about 1,000 km from north to south, and about 250 km from west to east. This brief description uses the place names as at 1919, with the modern names in brackets.

The Volga River empties into the sea at its north-western end; Astrakhan lies in the Volga delta. On the western side is the Caucasus with a population of Azerbaijani Moslems (often referred to as Tartars), Armenians, Georgians and Russians. Baku was an important city and port, with extensive oil facilities. North of Baku was Petrovsk (Makhachkala) and, further north again was Chechen Island, at the northern tip of the Lopatin peninsular. The eastern side of the sea constituted Russian Turkestan. There was a port, Krasnovodsk (Turkmenbashi) roughly opposite Baku; this was the western terminus of a strategic railway which ran through Central Asia to the Afghan frontier. Further north was Alexandrovsk (Fort Shevchenko).

The southern shores of the Caspian lay within Persia (Iran). However, these provinces were in revolt and the Persian government exercised little control there. In 1918, the British established a small base at Enzali (Bandar-i Anzali) at the south-western corner of the sea. From this base there was a very rough, tortuous and mountainous road of some 650 miles to Baghdad, headquarters of the British forces in Mesopotamia.

British involvement in the area began in the summer of 1918. Following the Russian revolution, there was concern that the Germans and their Turkish allies would advance to the Caspian, capture Baku with its oil-fields and refineries, and Krasnovodsk with its huge stock-piles of cotton. Enemy forces might then advance along the Transcaspian Railway to threaten India. The British despatched a small expedition under Major General Dunsterville to assist the provisional government in Baku to defend itself against the Turks. Dunsterforce, as it was known, held off a Turkish attack on Baku. However, the local forces proved to be cowardly, undisciplined and unmotivated, and Dunsterville withdrew his forces to Enzeli.

The new regime also had a small navy, known as the Centro-Caspian flotilla, and Dunsterville's command included a small naval contingent under Commodore David Norris to provide support for the mission. Norris chartered some merchant ships and armed them with field guns. They flew the Russian ensign and most of the crew was Russian; Norris's men manned the guns and operated the army radio sets.

The situation changed after the surrender of Germany and the Ottoman Empire. Although the Turkish threat disappeared, the British government still wanted to see stable, friendly states on the borders of India and decided to support the White Russian forces against the Bolsheviks. As at the beginning of 1919, Bolshevik forces held most of the territory around the northern part of the Caspian Sea including Astrakhan, which had a naval base containing a dozen destroyers and a pair of submarines. There were anti-Bolshevik regimes in Baku and Krasnovodsk.

Radio intercepts proved that elements of the Centro-Caspian flotilla were in secret communication with the Bolsheviks and the flotilla was disbanded in March 1918. Norris took over the best ships and set up a Royal Navy flotilla, flying the white ensign. Most of the ships were coastal freighters, armed with 4-inch or 6-inch guns; these included the Kruger (Norris's flagship), Ventuir (anglicised to Venture), Emile Nobel, Windsor Castle, Dublin Castle, and a couple of others. There were two sea-plane carriers and two Coastal Motor Boat carriers, with a total of twelve coastal motor boats. However, the sea-planes and the motor boats could operate only when weather conditions were favourable. More officers and ratings of the Royal Navy made the long journey across the mountains to join the formation, including Clark, who joined the Venture on 1 April 1919. In July 1919, at about peak strength, the Naval contingent in the Caspian numbered 47 officers and 1,063 ratings. In addition, there were 307 locally enlisted personnel - Russians, Tartars, Armenians.

A number of shore installations were set up. An old paddle-steamer was moved to Baku as an accommodation ship but proved to be too small; a block of flats was then taken over as "RN Barracks Baku", complete with sick bay, dental surgery and cells. The RAF set up their sea-plane base nearby. As the main area of operations was in the north, a forward operating base was established at Petrovsk. There was also an anchorage off Chechen Island much used by the ships, and the RAF established an airfield on the island, from which they operated forty DH9 and DH9A aircraft.

By mid-April 1919 the northern Caspian was free of ice, though there was often heavy fog, and both sides began naval patrols. The RAF mounted air raids on the Bolshevik naval bases near Astrakhan.

In May Norris received intelligence that the Bolsheviks had either captured, or were just about to capture, Alexandrovsk, a large harbour on the eastern side of the sea, and were also planning an attack on Petrovsk or Baku to obtain oil. On 14 May the flotilla sailed from Chechen with the intention of carrying out a reconnaissance with the motor boats or sea-planes. The wind making this plan unfeasible, Norris then steered directly for Alexandrovsk. Soon after dawn on the 15th they sighted a small convoy of three steamers towing two barges, escorted by a destroyer. When the British ships opened fire the steamers abandoned the two barges, which were sunk, and made off. The British ships gave chase at a rather ponderous nine knots until the quarry disappeared into the fog, then returned to Chechen. Prisoners from the barges confirmed that the Bolsheviks had occupied Alexandrovsk and that most of their fleet had been concentrated there preparatory to an attack on Petrovsk.

On 18 May a sea-plane from Petrovsk carried out a very daring reconnaissance of Alexandrovsk and reported the presence there of eight destroyers, five armed ships, fourteen armed motorboats and two gunboats. (In addition, there were two submarines, a minelayer and two small depot ships). Norris decided to attack and arrived off the port in the early hours of 20 May 1919. His squadron consisted of eight ships, including the Venture. Despite the marginal weather conditions, a sea-plane was launched to carry out reconnaissance and bombing but was unsuccessful in both tasks.

The next day dawned bright and clear and Norris approached the harbour with his entire squadron. Two or three destroyers were observed just outside the harbour, close to the land and heading north. Norris attempted to intercept them but they returned to the harbour at high speed. Norris still hoped to intercept them and pursued them into the harbour, which was 'V'-shaped, with its mouth at the north, and about six miles long. Emile Nobel and Venture took the lead and soon came under fire from the Bolshevik ships; Venture was straddled at 12:13 hrs. The general signal 'Open fire' was made. Venture hit a destroyer, inflicting such damage that she ran ashore among the fishing boats. Emile Nobel hit a large barge, which caught fire and was abandoned, but was herself hit in the engine room; she suffered casualties and damage but remained in action. The other enemy ships retired to the southern end of the harbour and sheltered behind barges and smaller craft. Their fire was still accurate and heavy, and a shore battery joined in. Norris wished to close the range, accepting that his slow and unhandy ships would have less room for manoeuvre as the harbour narrowed, and at 13.03hrs the British ships steamed further into the harbour in single line. Many of the enemy ships were on fire and spotting became increasingly difficult due to smoke. Emile Nobel reported that she would be unable to remain in action for much longer. At 13.30hrs the order to withdraw came. As the squadron proceeded out to sea, the volume of smoke from Alexandrovsk seemed to increase and loud explosions were heard. Emile Nobel and a ship which had broken down were sent back to Petrovsk under escort, leaving Kruger, Venture and the three carriers.

On the 22nd Norris ordered the motor boats to mount an attack but was frustrated by a breakdown of the radio sets. Instead, the one sea-plane still in service carried out five air raids on Alexandrovsk and sank a destroyer. That evening, most of the surviving Bolshevik ships left port and returned to Astrakhan; the night was very foggy, and their escape was unobserved.

On the morning of the 23rd, Kruger and Venture were suddenly confronted by two large Bolshevik destroyers and there was an exchange of fire. Although the latter had the advantage of range and speed, they failed to destroy the two British ships and soon made off to the north. A sea-plane was launched to attack the destroyers; the pilot could not locate them and carried out another raid on Alexandrovsk instead. Whilst returning from this raid the plane ran into fog and crashed into the sea. The pilot and observer were extremely fortunate to be rescued after spending thirty-two hours in the water.

Norris returned to Petrovsk with two ships on the 24th, leaving the remaining ships to patrol between Alexandrovsk and Chechen. On 28 May the squadron returned to Alexandrovsk for a close reconnaissance. Venture and other ships took up defensive positions inside the mouth of the harbour whilst the motor boats proceeded south, torpedoing a large barge on their way. On their arrival, a white flag was hoisted and a deputation came out and surrendered. It was confirmed that nine larger enemy vessels had been destroyed, together with a number of barges. There were no further encounters with the enemy and, for the remainder of their time in the Caspian, the sailorsaw out their time carrying out patrols from their Chechen anchorage in very hot weather. The British ships were unable to pursue the Bolshevik ships into their refuge in the Volga delta due to the very shallow water there, but assisted their White Russian allies to outfit motor gunboats for this purpose. The British then handed over their ships and the British Caspian Flotilla ceased to exist.

The record of the Caspian Flotilla was a creditable one. Although the Bolshevik ships had great superiority in speed and fire-power, the British ships sunk several of them and drove the rest from the Caspian Sea. Awards were approximately as follows:

Commodore Norris was appointed to be a Companion of the Order of St Michael and St George.

7 D.S.O.'s and 2 Bars.

8 O.B.E.'s.

3 M.B.E.'s.

5 D.S.C.'s.

18 D.S.M.'s and 2 Bars.

8 Royal Navy M.S.M.'s.

Around 32 M.I.D.'s.

Clark was probably awarded his D.S.M. for his work as a gunlayer. He had recovered his rate of Leading Seaman on 7 May 1919, was drafted back to Chatham in August 1919. On 15 January 1920 he was drafted to the Dragon, a light cruiser of the First Light Cruiser Squadron deployed with the Atlantic Fleet and was promoted Petty Officer on 1 October 1920.

Despite having completed only nine years of his twelve years' engagement, Clark was released from the Royal Navy on 18 June 1922 as part of the great retrenchment exercise referred to as the 'Geddes Axe'. He was awarded a gratuity of £191 to ease his transition back into civilian life.

Subject to 5% tax on Hammer Price in addition to 20% VAT on Buyer’s Premium.

Sold for

£1,800

Starting price

£1600