Auction: 22002 - Orders, Decorations and Medals

Lot: 188

(x) A fine Great War D.S.M. group of seven awarded to Major, late Colour Sergeant T. Boffey, Royal Marines

Distinguished Service Medal, G.V.R. (Ply. 9579. Col. Sergt. T. Boffey. R.M.L.I., H.M.S. Eskimo); 1914-15 Star (Ply. 9579 Sgt. T. Boffey. R.M.L.I.); British War and Victory Medals (R.M. Gnr. T. Boffey. R.M.), the BWM without unit; Defence and War Medals 1939-45; Hong Kong Coronation 1902, sometime silvered (Ply. 9579 Cpl. T. Boffey. H.M.S. Tamar 1902), this last fitted with straight-bar suspension and with engraved naming, mounted court-style as worn, very fine (7)

D.S.M. London Gazette 6 August 1915.

'For service on Eskimo with the 10th Cruiser Squadron, 1914-15. Served since the outbreak of the war and carried out most valuable work and whose services are deserving of recognition.' (ADM137/185/487 refers)

Thomas Boffey was born on 27 March 1879 at Knutsford, Cheshire, the second of the five children of Philip and Emma Boffey. In the 1881 census his father's trade is recorded as hay and straw dealer; ten years later, he was a greengrocer. His religion was Wesleyan, and he was originally a painter by trade.

In February 1899 Boffey enlisted as a Private in the Royal Marine Light Infantry (Plymouth Division) at Liverpool. For some reason he took a year off his age, giving his date of birth as 22 April 1880. After training at the RM Depot at Deal, he was posted to Vivid, the Plymouth Depot, where he quickly obtained promotion to Lance Corporal and then Corporal in July 1901. In November 1901 he began a two year tour of duty in Tamar, the depot ship in Hong Kong. During this period he participated in the ceremonies to mark the Coronation of King Edward VII in 1902, and was promoted to Lance-Sergeant.

On his return from the Far East he returned to Plymouth, where he served as a Drill Instructor. In 1902 and 1904 his character was rated only "Good" and this was sufficient to render him ineligible for the L.S. & G.C. Medal. In January 1905 he married his wife Edith at the Wesleyan Chapel, Saltash. In October 1905 he was awarded the Bronze Medallion of the Royal Life Saving Society for demonstrating proficiency in life-saving techniques and artificial respiration. He was promoted to Sergeant in 1906, and from then until the outbreak of the Great War he saw service in Blake, Arrogant, Hannibal and Gloucester.

In December 1914 Boffey was posted to Eskimo, attached to the 10th Cruiser Squadron. Eskimo was built in 1910 as a small passenger ship of 3,326 tons and was operated by the Wilson line between the British and Scandinavian ports. This was not her first service with the Royal Navy; in 1911 she had been chartered by the Admiralty for carrying official guests at the Coronation Naval Review at Spithead. In November 1914 she was requisitioned by the Admiralty, fitted out as an Armed Merchant Cruiser at Liverpool and allocated to the 10th Cruiser Squadron. The Squadron was engaged in enforcing the blockade of Germany in the seas between Scotland and Norway. The primary duty of the ships was to intercept ships and examine their passengers and cargo, to prevent Germans of military age returning to Germany, and to confiscate contraband.

The officers and ratings of the ships in the squadron came from a variety of sources; for this reason the squadron was often referred to as 'Fred Karno's Navy.' The Captain, Executive Officer and Gunner were officers on the Active or Retired lists of the Royal Navy; the remainder of the ship's company were from the Royal Fleet Reserve (former members of the regular Navy, often pensioners), the Royal Naval Reserve (merchant marine), Royal Marines, members of the Newfoundland Division of the R.N.R. and merchant navy volunteers. Depending on size each ship carried between twenty-five and forty-five Marines, who were often used as boarding crew and the Newfoundlanders, famed for their skills at small boat handling in heavy seas, manned the boats carrying the boarding crews to the ships they had intercepted.

Before taking up her duties on the blockade, Eskimo was sent on a mission to Russia. She sailed from Peterhead on 9 January 1915 and arrived at Alexandrovsk, near Murmansk, on 17 January. She began her return passage on 25 January and arrived at Scapa Flow six days later.

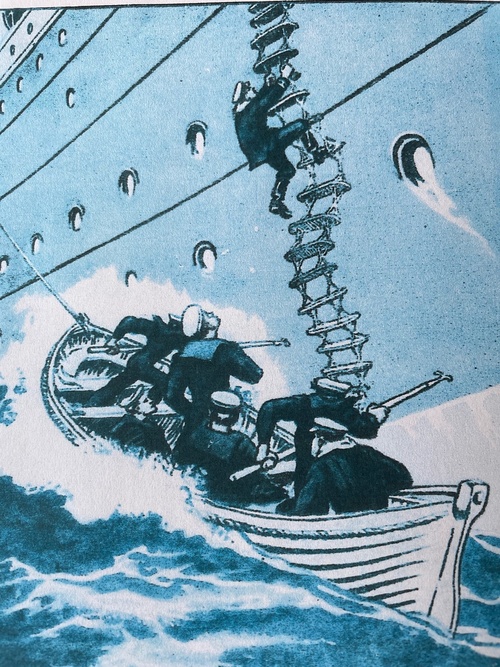

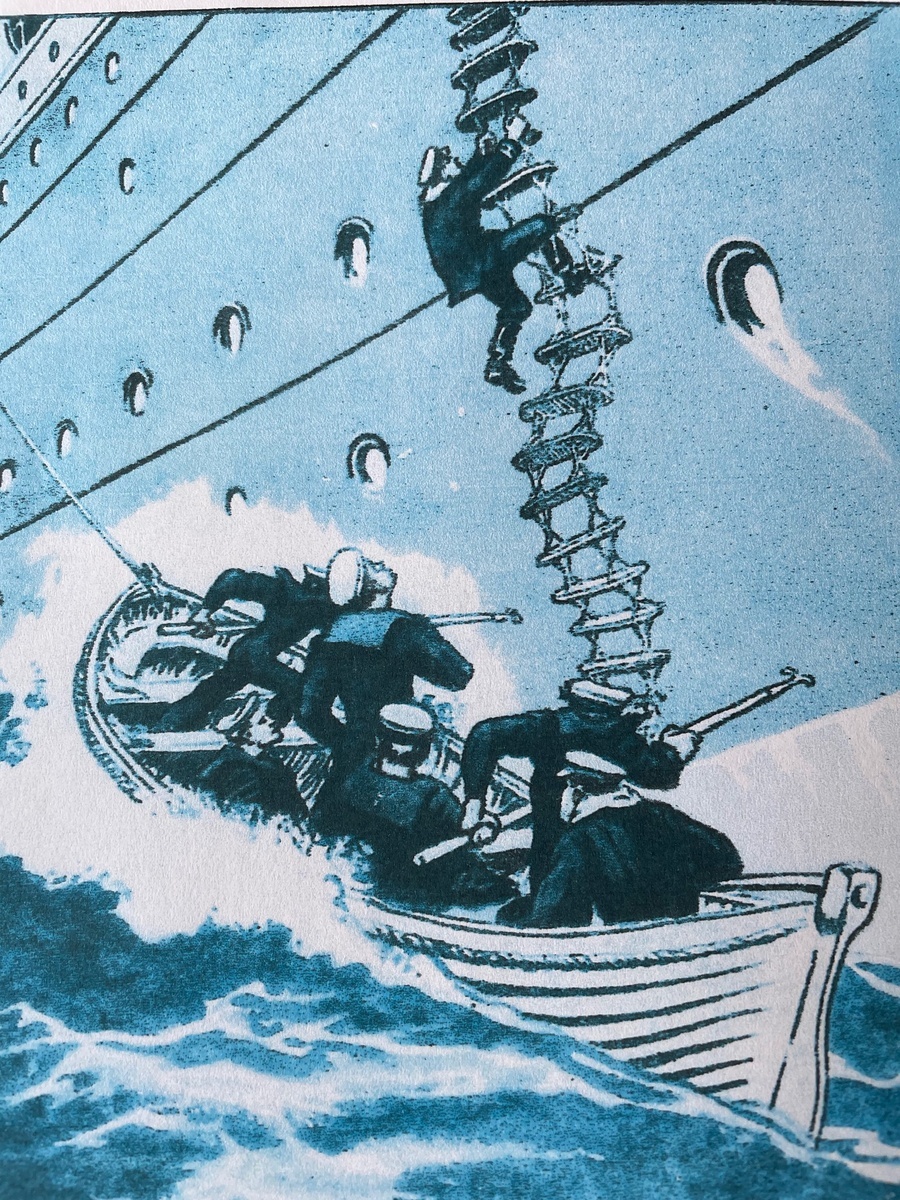

The ships were deployed on patrol lines; the Eskimo was on line 'D', running north-west from the Hebrides. The ships patrolled about twenty miles apart, each with lookouts high in the crow's nest scanning the horizon. Sometimes they had prior information of the approach of a neutral vessel, obtained from radio intercepts or intelligence sources. When a suspicious ship was observed, the patrol cruiser signalled to her to stop; not all complied, and some attempted to outrun them. The cruiser would then fire a shot across her bow. The patrol cruiser could not come too close to a suspicious vessel as she would risk being torpedoed if she were a German raider in disguise. One of the ship's boats would then have to row across a couple of miles of sea to the ship, where the boarding officer (a midshipman or sub-lieutenant) and boarding crew would have to scale the side of a strange ship. The crew might well be hostile and uncooperative. The officer would first conduct a quick check of the deck to verify that there were no concealed guns or torpedo tubes, which would then be signalled to the cruiser. He would then interview the skipper, check the ship's papers and, perhaps, check the cargo, although this could be dangerous and impractical at sea. If the ship were considered suspicious, a prize crew would be put aboard to bring her to a British port for a thorough examination. Boarding the vessels at sea was frequently very dangerous but, as Admiral de Chair, commander of the squadron noted in his despatch, "on the whole, very few accidents have occurred". Considerable tact and patience were required.

Winter in those northern waters was an arduous ordeal, with a succession of gales, freezing temperatures and mountainous seas. The ships were continuously at sea for three to six weeks, depending on their fuel capacity. Officers and men had to keep their watches and look-outs in blizzards of snow and hail and, when off watch, the violent movement of the ship often made it difficult to rest. Eskimo was one of the smallest ships in the squadron and the fact that she survived the winter of 1914-15 was regarded as remarkable. Some extracts from her Log:

'6 Feb (in Scapa Flow) Fore signal yard broken by force of wind. On the same day, she observed a destroyer that had been driven ashore.

17 Feb. at 00.30 hrs, a heavy sea struck the poop, carried away the shot rack and washed overboard nine 6-inch projectiles. At 03.00 the ship was labouring heavily and shipping large quantities of water.'

Despite this, she continued to patrol and send her boats away to check suspicious vessels. On 18 February there was an accident when hoisting in the boat and all the boat's gear was lost, but there was no mention of injuries.

That same month another of the squadron's ships, Clan McNaughton, was lost with all hands. The cause of her loss was unknown but many believed that she had foundered in a gale. The Navy then recognised that small ships were unsuitable for patrolling the exposed waters north of the Hebrides and the two smallest ships of the squadron, Eskimo and Calyx, were decommissioned and returned to the Wilson Line. In 1916 Eskimo was captured by the Moewe, and taken to Germany.

The blockade was successful. Between 24 December 1914-11 May 1915, some 926 ships were boarded and examined; 258 of these were found to be carrying contraband and were sent with prize crews to ports in the Shetland or Orkney Islands. In his despatch of 11 May 1915 Admiral de Chair noted that the men under his command had carried out their trying duties with unfailing cheerfulness and devotion, and displayed very high qualities of seamanship. He recommended forty-one men for decorations; this was later whittled down to twenty-four. According to Britain's Sea Soldiers his award was for '...services in patrol cruisers, where (he was) engaged in the hard and dangerous work of boarding and armed guards of the suspected ships.'

By this time Boffey had been promoted to Colour-Sergeant and posted back to Plymouth. In December 1915 he was sent to Excellent, the gunnery school at Whale Island and, in June 1916, was promoted to Royal Marine Gunner (a Warrant Officer rank). In September 1916 he was appointed to the battleship Temeraire, deployed in the Grand Fleet at Scapa Flow. Towards the end of 1918 she was transferred to the East Mediterranean Squadron. Following the surrender of Turkey, she was sent to Russia to protect British interests in the civil war, and entered Sevastopol on 26 November 1918. Boffey left the ship in May 1919, then served briefly in the battleship Colossus and battle-cruiser Glorious.

In his confidential reports of this time his conduct was described as satisfactory, while his ability was rated average or above average. He was described as zealous, capable and reliable, but at times lacking in tact. He was a crack shot with rifles and revolvers and a skilful instructor. He was recommended for further advancement '...in due course'. In June 1926, while serving in Valiant, he was commissioned. He retired with the rank of Lieutenant in April 1930.

Despite being 60 years old Boffey was recalled for further service on the outbreak of hostilities in 1939. He was promoted to Captain and appointed a Company Commander in the 19th Battalion, Royal Marines. Few of those who served at Scapa Flow recalled the place with any pleasure - the foul weather, rough seas, almost constant darkness in winter, boredom and the total lack of amenities and shore facilities. At the end of the Great War Boffey probably experienced a feeling of relief that he would never have to see the place again, and must have been dismayed when the 19th Battalion was employed throughout the war in the Orkneys and Shetlands. He was commended for good service by the Vice Admiral Commanding. He was released in 1945 with the rank of Captain, Acting Major. The Major died in December 1969, aged 90; sold together with his engraved Royal Life Saving Society Medal.

Subject to 5% tax on Hammer Price in addition to 20% VAT on Buyer’s Premium.

Sold for

£1,500

Starting price

£1000