Auction: 17002 - Orders, Decorations and Medals

Lot: 391

Sold by Order of the Family

'At 3 a.m. on 7 June [1940], Cross spotted in the Arctic daylight four Heinkel III bombers beginning a shallow dive attack on their airfield. He damaged one himself, then the port tank on his Hurricane was blown to pieces and a bullet hit the side of the windscreen; but it missed Cross's head because he had failed to put on his harness and was crouched forward over the control column; he managed to glide back from a height of 4,000 ft. to the airfield.

Since 'Glorious' was not equipped with arrester hooks for Hurricanes, Cross had sandbags placed in their tails when 46 Squadron's 10 remaining aircraft landed on the flight deck. Eventually all arrived safely, and Cross turned in at 4.30 a.m. after a warming mug of cocoa. He was awakened by the sounding of actions stations.

Cross reached the flight deck as a shell tore a hole 15 ft. away, and more landed around him as he made for the quarterdeck at the stern of the carrier. The hangars caught fire. "Bad luck your Hurricanes got it with the first salvo," shouted a passing Fleet Air Arm pilot over the din of the continuing crashes and explosions. Then the public address system packed up, and the word to abandon ship was passed from man to man.

Inflating his Mae West, Cross jumped overboard and swam to a Carley float, where he was joined by his New Zealand-born Flight Commander, Squadron Leader Pat Jameson, with a "Permission to come aboard, sir?" Soon they were joined by 35 other survivors. Attaching a shirt to an oar for a sail and mast, they found there was no food or water; then a naval warrant officer came up with a small tin of brown sugar. By 11 June, after they had spent 70 hours exposed to the Arctic weather, a Norwegian fishing vessel picked up Cross, Jameson and the four other survivors. They were taken to the Faroes where they joined the destroyer 'Veteran'.

Suffering from considerable pain in their feet, Cross and Jameson were landed at Rosyth a week later, and sent for treatment at the Gleneagles Hotel which had been turned into a military hospital.'

High drama over and off Norway: The Daily Telegraph's obituary notice for Air Chief Marshal Sir Kenneth 'Bing' Cross, K.C.B., C.B.E., D.S.O., D.F.C., refers.

The outstanding post-war K.C.B., Second World War C.B.E., D.S.O., D.F.C. group of sixteen awarded to Air Chief Marshal Sir Kenneth 'Bing' Cross, Royal Air Force, whose remarkable career embraced gallant squadron command in Norway in 1940 - and his miraculous survival from the controversial loss of the carrier H.M.S. Glorious - to unprecedented pressure as Bomber Command's C.O. at the time of the Cuban missile crisis in 1962

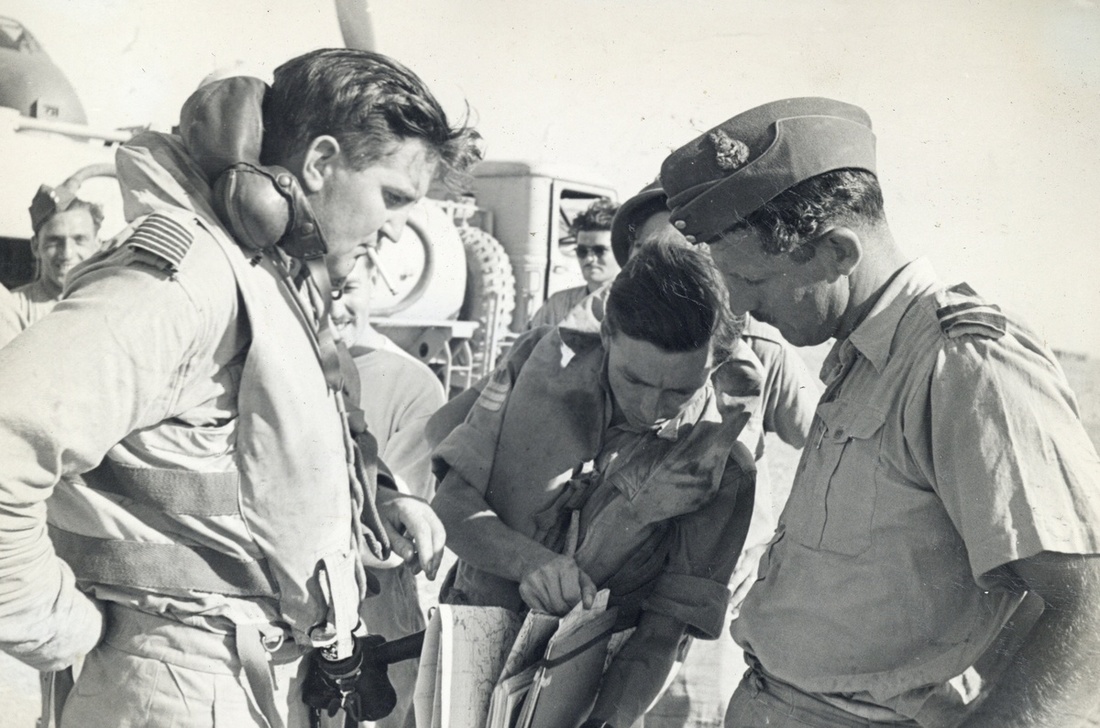

No stranger to onerous command, 'Bing' Cross had in the interim served as a Wing and Group Leader in North Africa and Italy in 1941-44, a period in which he displayed 'indomitable courage': it is an inspiring story of leadership and gallantry, vividly - yet modestly - recounted in his appropriately entitled autobiography Straight and Level

His stoicism in facing much bereavement is also a part of that story, from the loss of most of his fellow pilots in the Glorious in June 1940 to the Gestapo's murder of his brother, Squadron Leader Ian Cross, D.F.C., following his part in the famous 'Great Escape' at Sagan in April 1943

(i)

The Most Honourable Order of the Bath, K.C.B. (Military), Knight Commander's set of insignia, comprising neck badge, silver-gilt and enamel, and breast star, silver, with silver-gilt and enamel appliqué centre, in its Collingwood Ltd. case of issue

(ii)

The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire, C.B.E. (Military) Commander's 2nd type neck badge, silver-gilt and enamel, in its Garrard & Co. case of issue

(iii)

Distinguished Service Order, G.VI.R., silver-gilt and enamel, the reverse of the suspension bar officially dated '1942'

(iv)

Distinguished Flying Cross, G.VI.R., the reverse officially dated '1940'

(v)

1939-45 Star

(vi)

Air Crew Europe Star

(vii)

Africa Star, clasp, North Africa 1942-43

(viii)

Italy Star

(ix)

War Medal 1939-45

(x)

Coronation 1953

(xi)

France, Legion of Honour, Commander's neck badge, silver-gilt and enamel, in its case of issue

(xii)

France, Croix de Guerre 1939, with bronze palm

(xiii)

Norway, War Cross 1941

(xiv)

The Netherlands, Order of Orange Nassau, Commander's neck badge, with swords, silver-gilt and enamel, in its J. M. J. van Wielik case of issue

(xv)

United States of America, Legion of Merit, Officer's breast badge, gilt and enamel, the reverse engraved 'Kenneth B. B. Cross', mounted court-style as worn where applicable, lower point of left arm on K.C.B. star slightly bent and usual damage to Legion of Honour arm points and enamel, otherwise generally good very fine (16)

K.C.B. London Gazette 13 June 1959.

C.B.E. London Gazette 8 June 1944. The original recommendation states:

'Since February 1943, this officer has been in command of the Group which has been responsible for the Air Defence of Tunisia, the protection of convoys passing through the central Mediterranean from air and submarine attack, for offensive action against the enemy shipping running locally to Sicily, Corsica and Sardinia, and for air sea reconnaissance. The Group played a most important part in attacking enemy shipping and air transport moving to and from Corsica and Sardinia. After the landing in Italy its operations have been particularly successful in stopping enemy shipping running to and from the Adriatic. All these operations have been most successful and this is attributable to the outstanding ability, leadership and drive of Air Commodore Cross.'

D.S.O. London Gazette 13 February 1942:

'Since the commencement of operations in the Libyan campaign, this officer has displayed inspiring courage and leadership. In spite of his onerous duties on the ground, Group Captain Cross has constantly participated in the air operations and his indomitable courage and skill have contributed materially to the fighting efficiency of the force he commands.'

D.F.C. London Gazette 13 September 1940. The original recommendation states:

'This officer commanded No. 46 Squadron from 30 October 1939 to 8 June 1940. By his enthusiasm and personal leadership he maintained a very fine offensive spirit in his squadron. He led many convoys patrols in all weathers. He took the Squadron to Norway and whilst operating there they shot down 19 enemy aircraft. Since Squadron Leader Cross has been in command, his squadron has destroyed a total of 26 enemy aircraft. He is one of two survivors of No. 46 Squadron who embarked in H.M.S. Glorious.'

Covering remarks:

'Squadron Leader Cross was previously recommended by Wing Commander Hutchinson as follows:

During the evacuation of Norway on 8 June 1940, Squadron Leader Cross was responsible for leading his squadron to H.M.S. Glorious, and for the successful landing-on of all aircraft by pilots who had never previously landed on a deck while flying Hurricanes. This officer also displayed resolution and courage after the sinking of H.M.S. Glorious under what seemed hopeless circumstances, by leading and encouraging 29 survivors who were on a raft in the North Sea for two days and three nights. When rescued there were only five survivors remaining. On 5 June 1940, Squadron Leader Cross assisted in shooting down an enemy aircraft over Bardu Foss.'

Kenneth Brian Boyd Cross - universally known as 'Bing' - was born at East Cosham, Hampshire on 4 October 1911, the son of Pembroke and Jean Cross. His father was an estate agent and surveyor in Portsmouth and young Kenneth attended Hilsea College before moving to Kingswood School in Bath in 1927: in common with many great warriors, he excelled at sports but failed dismally in the classroom.

Wings - Bader - Hendon Air Display Team

His father having fallen on hard times, he had to leave school at 16 and found work at a local garage. On reaching 18, he opted for a career in the Royal Air Force and made a successful application for a short service commission in April 1930. Following at least one impressive prang, he qualified as a fighter pilot and was posted to No. 25 Squadron at Hawkinge, Kent. On attending a course at Sutton Bridge, in May 1931, Cross had a memorable encounter with Douglas Bader. Straight and Level takes up the story:

'He was indeed a most exceptional character and meeting him made such an impression on me that today, more than 60 years later, I remember the occasion as clearly as if it were yesterday. We introduced ourselves and, chatting about this and that, quickly found that our interests were very much the same, flying and games, most especially rugby. As he was already playing for the Harlequins at this time I remember much of the conversation centred round the 'great game'. My first impression was of a young man with complete confidence in himself and with absolutely no doubt that all his beliefs and opinions were correct. We started a friendship.'

Another shared interest was participation in the Hendon Air Displays and in that respect Cross quickly displayed a talent for aerobatics. On his squadron being re-equipped with the Hawker Fury, he was among those selected to undertake the squadron formation display at the 1933 and 1934 Hendon Air Displays: during this period Cross was part of 'C' Flight which perfected a barrel roll in formation, the first time such a manoeuvre had been achieved.

In June 1936, he was delighted to obtain a permanent commission in the rank of Flight Lieutenant, and was attached to the Cambridge University Air Squadron. Owing to the excellent golfing facilities at Cambridge, he was reluctant to leave when ordered to join H.Q. No. 12 Group as an Auxiliary Liaison Officer under Leigh-Mallory.

Norway

In October 1939, and having been advanced to Squadron Leader, Cross was appointed to the command of No. 46 Squadron, a Hurricane unit based at Digby, Yorkshire. A flurry of convoys patrols over the North Sea ensued, together with a period of ineffective night fighter sorties. Then in May 1940, 46 was ordered to join the carrier H.M.S. Glorious in support of the Norwegian campaign. Fledgling Eagles takes up the story:

'That same evening [26 May 1940], Glorious arrived again off the coast with six Hurricanes ranged on deck, but there was some initial doubt as to whether there was sufficient wind or enough deck length for a safe take off. The Commanding Officer of 46 Squadron, Squadron Leader K. B. B. Cross, made the first attempt however, and got into the air without difficulty. At once the others followed, and the first flight landed at Skaanland at 2130, although one Hurricane nosed over on a patch of soft ground. The second flight followed, but the first of these to go in also nosed over, and the rest flew off to land at Boardufoss instead.'

In the short period of operations that ensued, prior to being evacuated in the Glorious - and notwithstanding the quality of landing grounds - 46 Squadron flew no less than 249 sorties, including 19 interceptions with a resultant bag of 11 victories: it was a remarkable achievement and Cross, as C.O., was much to fore, flying twice as many sorties as any other pilot.

On 5 June 1940, he was flown out to Glorious in a Walrus to discuss the fate of 46 Squadron's Hurricanes. He had been ordered to organise their destruction on the completion of the evacuation for no-one believed that could be landed on the carrier without 'arresters': he begged to differ and by means of employing sandbags as ballast in the rear fuselages of his aircraft he was proved right.

The surviving Hurricanes aside, nine of 46's pilots were embarked with Cross in the Glorious; three others and the Squadron's ground crew in the M.V. Arandora Star.

In making her way independently back to Scapa on 8 June, Glorious ran into the mighty Scharnhorst and Gneisenau. The enemy opened fire at 20,000 yards range at 1630 hours, quickly gaining direct hits and, hopelessly outranged, the Glorious was all but dead on the water by 1720 hours: crashes and explosions were now continual and fires raged out of control with billowing clouds of black smoke enveloping the carrier.

The order to abandon ship having been given, Cross removed his shoes, jumped overboard and swam to a Carley float. Much to his delight, he was quickly joined by one of his pilots, Pat Jameson. Straight and Level takes up the story:

'It is difficult to estimate from sea level, but Glorious seemed to stop about a mile away with a heavy list to starboard and then two enormous German ships, which we now know were the Scharnhorst and Gneisenau, came past quite close to us. I thought they were certain to pick us up so I threw my file of squadron records and my logbook into the sea. Alas, I need not have worried about security. The German ships didn't stop and, having passed us, turned away and were soon out of sight. I did not actually see the Glorious sink as I had my back to her at the time. Our hopes were now pinned on the remaining destroyer, Acasta, which was in sight but soon disappeared. We know now that she was sunk after gallantly attacking and hitting the Scharnhorst with a torpedo.

So now there were no ships, either of our own or the enemy. All around there were Carley floats, rafts and wreckage with figures clinging to them. The sea was rough and very cold - we were after all about 100 miles inside the Arctic Circle. We had 37 on our float but they began to die one by one within a few hours. Strangely, it was some of those who looked physically toughest who went first. A stoker, partially unclothed, gradually became unconscious and slipped into the well of the float. We held his head above the water but he died soon afterwards. There was nothing for it but to push him over the side. This sad proceeding was repeated at intervals. Men would slide into the well, we would pick them up and push them over the side. Again and again. Most of the deaths took place in the first few hours, due rather more to people giving up hope than wounds or lack of clothing. Owing to the perpetual daylight we had no idea of the passage of time, but periodically it would get colder and we assumed that this was night. It was real misery and the rough sea and wind meant we were constantly wet through and cold. Our companions continued to die … Sadly only seven now remained, and surprisingly one was Geordie, the marine, who had nothing to keep him warm but his tunic. Our party now consisted of Geordie, a Warrant Officer R.N., three sailors, Jameson and myself.'

Salvation finally arrived in the form of the S.S. Borgund, a small Norwegian fishing vessel:

'Gradually she got larger and then came the ecstatic moment when she was so near that we knew she must have seen us. We all started shouting our heads off and waving anything we could lay our hands on. We forgot entirely our thirst and the pain in our feet. At last she stopped right by us, a rope was thrown, seized and we were pulled alongside where a rope ladder was hanging. I seem to remember I was first up and was grabbed by willing hands at the top. Soon we were all aboard and led away to resting places. The day turned out to be Thursday, 11 June and the time about 3.15 p.m., so 70 hours had passed since the Glorious went down about 5.30 p.m. on Saturday, 8 June. All seven of us had survived, though one died later in hospital of gangrene' (ibid).

A long period of recovery ensued, latterly at Gleneagles Hotel, which had been taken over for use as a military hospital: 'the doctors did relent a bit when the pain was at its worst and we were given morphia injections which helped us sleep'.

He was awarded the D.F.C., in addition to the Norwegian War Cross (London Gazette 6 October 1942, refers).

In late August 1940, Cross was advanced to the acting rank of Wing Commander and passed fit for light duty and, still wearing carpet slippers on his feet, reported to Fighter Command's 12 Group H.Q. as a Group Controller: he was warmly greeted by Leigh-Mallory, who congratulated him on his D.F.C.

However, as Cross later recounted, 'the position of Group Controller soon began to pall with me and I longed to be back on flying. My feet were improving and the medicos said that another month would see them all right for a medical board inspection.' Emboldened by this promising prognosis, he enlisted the assistance of a former Harlequins friend at the Air Ministry and gained a posting to the Middle East: he was embarked in Glorious's sister ship, the Furious, which left him feeling a little uneasy.

North Africa and Italy

Originally earmarked for a Staff position, he was in fact appointed to command No. 252 Wing and given the onerous responsibility of overseeing the air defence of western Egypt.

Then in late 1941, and having been advanced to the acting rank of Group Captain, Cross was appointed to the command of No. 258 Wing at Sidi Barrani. He subsequently led Hurricane sorties 'over the wire' in support of Operation "Crusader" and proved instrumental in engaging an armoured column Rommel had sent out behind our forward troops: 'We found the column without difficulty because of the enormous cloud of dust it was kicking up by its high speed.'

A week or two later his Hurricane was hit in a sweep over Gambut airfield and, as a result of the damage incurred, it somersaulted on landing. Cross took a crack on his head was admitted to hospital. He was mentioned in despatches (London Gazette 1 January 1942, refers).

When 258 Wing was upgraded to a Group, he returned to 252 Wing at Alexandria and, following the advance from El Alamein in October 1942, commanded it in support of 1st Army's operations in Tunisia. Such onerous ground duties aside - and as cited in the citation for his subsequent award of the D.S.O. - 'he constantly participated in the air operations' and his 'indomitable courage' contributed materially to the fighting efficiency of his Wing.

During his command, Cross was invited to a 'desert lunch' with Winston Churchill:

'Within a few weeks I had met Churchill, Smuts and Trenchard, three men to whom the adjective great could rightly be attached. I had already met many military figures, Cunningham, Longmore, Tedder, O'Connor, Freyberg, Dowding, Park and Coningham. I was to meet and observe at close quarters Eisenhower, Alexander, Montgomery, Bradley, Patton, Portal, Slim, MacMillan and Attlee. All were impressive men in their way but none of quite the same greatness as Smuts, Trenchard and Churchill. All very different, but all with an aura about them. There was one quality that they had in common: an instant ability to assess a situation when meeting a number of people, even an unexpected audience, and then the ability to address them with authority' (ibid).

In early 1943, Cross assumed command of No. 242 Group, in which capacity he lent valuable service in support of the Tunisian campaign and Operation "Husky" - the Sicily landings. On moving to the Italian mainland, the Group's brief expanded from air defence and tactical support to embrace shipping strikes and reconnaissance work. He had meanwhile been appointed to the temporary rank of Air Commodore. He was awarded the C.B.E.

H.Q. Allied Expeditionary Air Force and Director of Overseas Operations (Tactical)

In March 1944, Cross returned to the U.K. to work under his old boss, Leigh-Mallory, who was now the Air C.-in-C., Allied Expeditionary Air Force. In this capacity, together with his American counterpart, he was tasked with the conversion of R.A.F and U.S.A.A.F. fighter squadrons from an air fighting role to that of ground attack. With the invasion of France underway the training requirement was reduced and he requested to return to operations in a reduced rank: Portal had other ideas and he was posted to the Air Ministry as the Director of Overseas Operations (Tactical), in which capacity he ended the war.

In addition to being appointed a Commander of the French Legion of Honour and awarded the Croix de Guerre in 1944, Cross was awarded the American Legion of Merit (London Gazette 11 April 1944, refers), and appointed a Commander of the Order of Orange Nassau (London Gazette 18 November 1947, refers).

Post-war - Head of Bomber Command - Cuban missile crisis

Now marked out for senior command, and having attended the Imperial Defence College, Cross was appointed to the substantive rank of Group Captain at Operations, H.Q., B.A.F.O., Germany: this phase of his career included being closely involved in the planning of the Berlin airlift.

In the early-to-mid 1950s, and on being advanced to Air Commodore, he served as Director of Operations, Air Defence, in which capacity he was awarded the C.B. (London Gazette 10 June 1954, refers). He next served as A.O.C. No. 3 Group, Bomber Command (1956-59), when he had charge of the Group's new Valiant and Victor nuclear deterrent V-bombers.

Advanced to Air Vice-Marshal in January 1956, Cross reached the pinnacle of his career on being appointed A.O.C.-in-C. Bomber Command. It was an inspired choice in which he established close relations with the leaders of the U.S. Strategic Air Command: this was fortuitous for his period of command embraced the Cuban missile crisis of 1962, when he brought his Vulcan and Victor crews to unprecedented and prolonged states of quick reaction alert.

He was appointed K.C.B. and promoted to Air Marshal.

His final appointment was as A.O.C.-in-C. Transport Command and, having attained the rank of Air Chief Marshal in October 1967, he was placed on the Retired List.

Cross courted his future wife Brenda in typically forthright fashion: having bumped into her at the War Room in Whitehall in 1944, he married her within a month. It was a happy liaison cruelly curtailed by her murder at a Chelsea antiques shop in 1991.

Always a keen sportsman - he had played rugby for Harlequins as well as the R.A.F. - and a man who knew his own mind, Sir Kenneth died on 18 June 2003, aged 91.

Sold with an impressive supporting archive of photographs and documentation, comprising:

(i)

The recipient's R.A.F. Pilot's Flying Log Books (Form 414 types) (6), covering the periods May 1930 to June 1932; July 1932 to April 1935; May 1935 to May 1937; January 1941 to December 1957; January 1958 to April 1960; and January 1958 to January 1967, this last privately bound: as described by the recipient in Straight and Level, his Flying Log Book covering the period June 1937 and June 1940 was purposely discarded at the time of Glorious's loss and he didn't return to flying duties until January 1941.

(ii)

The recipient's warrants for his K.C.B., dated 13 June 1959, and C.B. dated 10 June 1954, both in their Central Chancery forwarding envelopes.

(iii)

Wartime - April 1940 - group photographs of the pilots of No. 46 Squadron and of the entire squadron, including ground crew, both on titled card mounts, the former particularly poignant in view of coming events in Norway.

(iv)

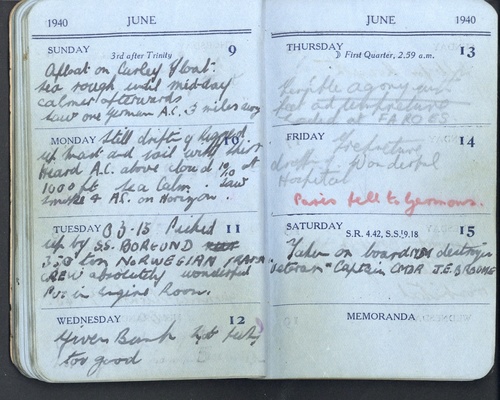

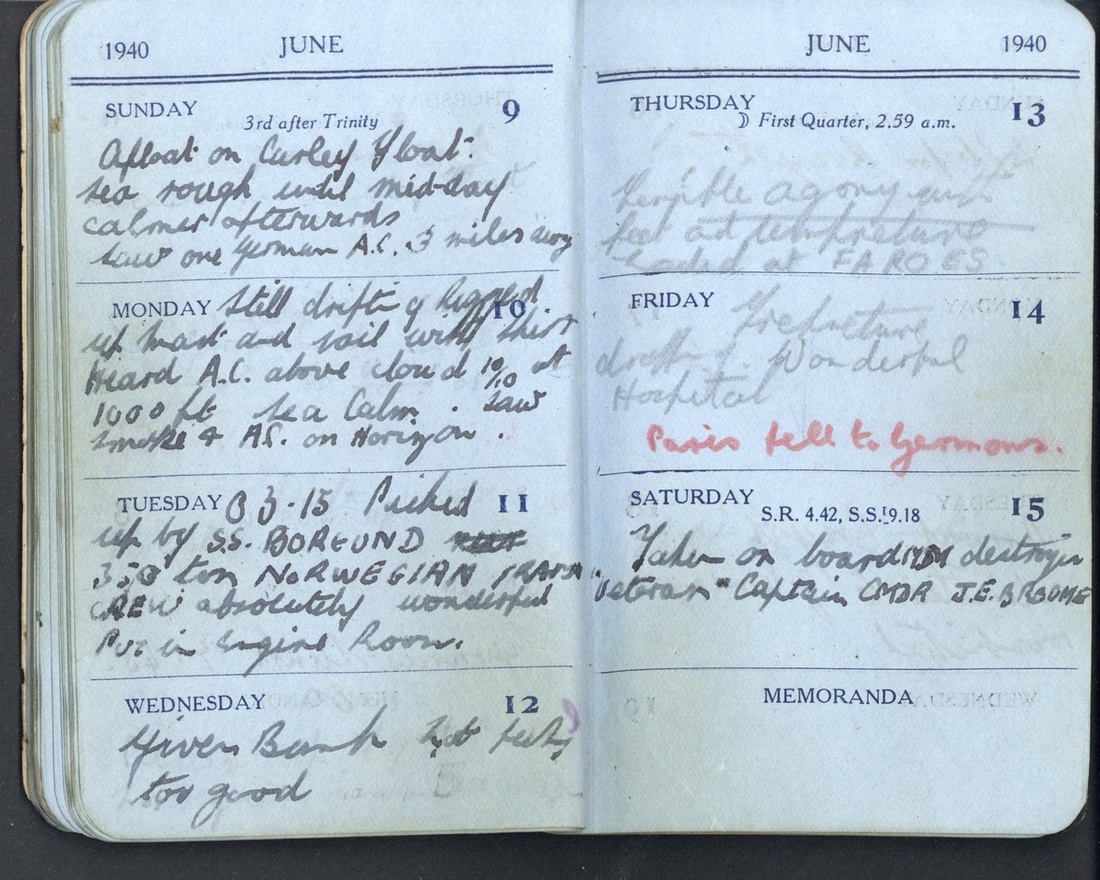

An emotive 'survivor' of the loss of Glorious: the recipient's water-damaged 1940 pocket diary, with a number of entries pertinent to the Norwegian campaign, contained in its original leather wallet.

(v)

Four scrap books containing a mass of photographs, newspaper cuttings, invitations, telegrams and letters, the first three albums dated 'January 1930 to December 1934', '1935-43' and '1943'; the letters including a message from Leigh-Mallory in respect of No. 46 Squadron's departure for Norway, in addition to a letter of condolence on learning that the recipient's brother had been murdered Gestapo, dated 20 May 1944, and likewise a congratulatory message on the award of the recipient's C.B.E. in June 1944; letters of thanks from Lieutenant-Generals L. W. Allfrey and K. Anderson, G.O.C. 1st Army, in respect of the recipient's leadership and command in North Africa; an Air Ministry letter to the recipient's father, reporting that his son had been admitted to hospital at Gleneagles, dated 3 July 1940, and much besides.

Additional reference sources:

Cross, Air Chief Marshal Sir Kenneth, K.C.B., C.B.E., D.S.O., D.F.C., with Professor Vincent Orange, Straight and Level (Grub Street, London, 1993).

Shores, Christopher, Fledgling Eagles (Grub Street, London, 1991).

The Daily Telegraph, 19 June 2003; obituary notice.

Subject to 20% VAT on Buyer’s Premium. For more information please view Terms and Conditions for Buyers.

Sold for

£17,500