INSIDER 30 | A GENERAL WITHOUT A NATION (OR MEDALS)

by Edward Hilary Davis

Few will have heard of Richard Guyon, a soldier originally born in Walcot near Bath in 1813, the fifth generation of a military Huguenot family. Nor will anyone know him by his other names and titles: General Le Comte de Guyon, Gróf Guyon Richárd, or Kurshid Pasha. Yet this relatively overlooked Brit witnessed, and took part in, some of the historic moments of mid-19th century Austro-Hungary, Turkey and the Crimea. His story is certainly one worthy of a good blockbuster. He is also possibly the only Brit to be awarded a rare and short lived order – the Hungarian Order of Military Merit.

Guyon, known as ‘Dick’ to his family, was the son of a Royal Naval Commander, John Guyon, whose own Napoleonic war tales couldmatch the exploits of ‘Lucky Jack’ in Patrick O’Brian’s Master and Commander. Richard Guyon received a brief military education; commissioning into the Surrey Militia, he served in the Portuguese Liberal Wars. In 1832 he entered the service of the Austrian regiment of Archduke Joseph’s 2nd Hussars – a ‘smart regiment’. This may have been because he had struggled to purchase a good commission in the British Army. Nevertheless he appears to have been a successful socialite in the world of the Austrian court, becoming ADC to his commander Field Marshal Baron Ignaz von Splény de Miháldi, who was Privy Councillor and Chamberlain to the Emperor and King, and Grand Captain of the Hungarian Noble Guard. Guyon later marrying the Field Marshal’s daughter, Marie. His social status in both Austrian and Hungarian circles rose yet again when, through his friendship with the French Ambassador to the Austrian Court, who provided documents, he was recognised in his French ancestor’s title of Count, something which had not been possible in England.

Gróf (Count) Guyon, now married to the cream of Hungarian military aristocracy, enjoyed a life of a country gentleman on his inlaws’ estates near Komárom. 1848 was a year of revolutions in Europe. In London, Italy, France, the German Confederation, the Netherlands and the Austrian Empire, populations began to demand democracy, freedom of the press and the upsurge of nationalism. This was particularly explosive in Hungary, which, hitherto, had been the ‘second nation’ in the Austrian Empire – it quickly became a war of independence from the Habsburg-ruled Empire. Count Guyon entered the service of the new National Government Forces and served in several early battles against the Austrian forces, discovering that he had a flair for command, a great care for his troops, and often showed indomitable courage.

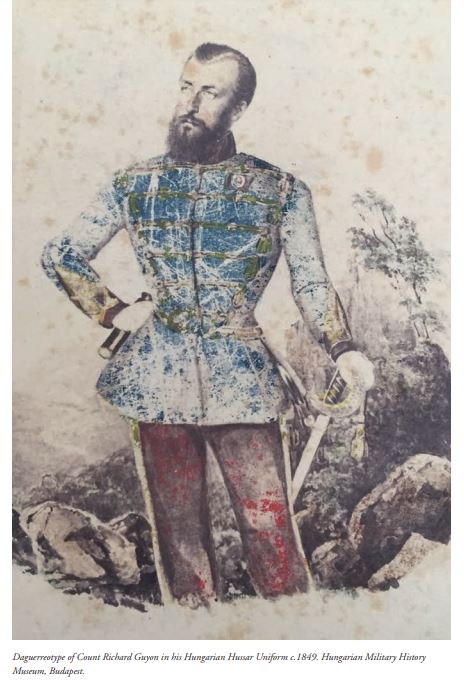

He was made a General and commanded several victories against the Austrians, defeating Count Josip Jelacic at the Battle of Hegyes in 1849. While Governor and defender of the castle town Komárom, he heroically rescued the town from total destruction. In a famous incident he spoke to fleeing Hungarian troops - he urged them on, ‘call yourselves Hungarians? You are not Hungarian, you’re sh*t!’ This apparently helped! Guyon, like many other new Hungarian Generals, was awarded the Order of Military Merit, first as a knight then commander. As all the honours and decoration hitherto where in the gift of the Habsburgs, including the Royal Hungarian Order of St Stephen established by Maria Theresa; the revolutionary government had made designs for a new, uniquely Hungarian order, with civil and military divisions. Plans were made but as the war took priority, they were not able to award any actual medals of the original design. The temporary way of wearing these medals was to sew on a piece of ribbon (red for military, green for civil) and attach a silver circlet of laurel – for knights, and a further golden Hungarian cross – for commanders.

These two grades can be seen on Guyon’s uniform at the Hungarian Military History Museum in Buda. After the war’s end, while in exile, some Hungarians were actually able to have their medals made, but only by local jewellers (in Italy for example), so there is little uniformity on surviving editions. Today’s Hungarian Order of Merit is a derivation of the original order and is not dissimilar to the first design. Despite a brave action of self-sacrifice by Guyon’s battalions at the Battle of Szőreg, 5th August 1849, the War of Independence failed at Temesvár a few days later – partially due to the Austrians obtaining the help of the Russian Imperial Army. Guyon, his family and many other revolutionaries went on the run eventually escaping capture and fleeing to the Ottoman Empire. Having lost almost everything in the plight, Guyon entered the service of the Sultan being made a general of division and appointed Governor of Damascus – as such he was awarded the title of Pasha (akin to a Peerage in the UK). The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography claims that he was the first Christian to obtain the rank of Pasha without having to convert to Islam. As the Crimean war began in 1853, Guyon was mobilised and helped liaise between the Turks, the French and the British. He did much to prepare the Ottoman forces for European ‘conventual war’ and defended Kars against the Russians. However, at what seemed to be the turning point of his career and the moment where it seemed he would enter the pages of history, he died of cholera at Scutari, along with many other soldiers.

Family rumours of poison by jealous Turkish officers exist, although it may well have been the Austrians. He remains a ‘what might have been’ character – had there been a British born senior Turkish General commanding in the Crimea, who knows which country he would have ended up serving next. There were discussions about him being offered a command in the British forces, though it seems unlikely he would have been trusted. Many mourned his death in several nations.

His now poverty-stricken family eventually travelled to France where their care was highly regarded by Napoleon III, who curiously paid for the two boys’ education. The younger son, Count Edgar, returned to Hungary where he died, bequeathing items to the Military Museum. British Newspapers mourned Guyon too. The Turks lost a valuable leader but they had a number of experienced Hungarian generals on their staff. He is best remembered in the country he adopted as home.

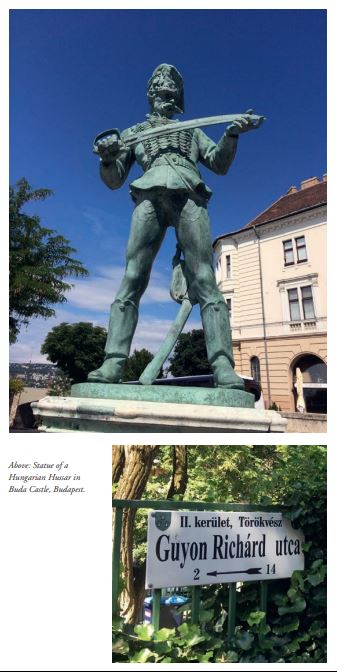

Several Hungarian streets are named after him as well as ‘blue plaques’ where he lived, and his words are sometimes quoted by politicians. The Military History Museum in Buda has some of his things on display, and in 2015 the President of Hungary presented a statue of Guyon to the Military History Museum in Istanbul. It is unclear whether this general, like his fellow exiles, was awarded the Order of the Medjidie, or the Turkish Crimean medal, or the British Crimea medal or indeed any French honours.

Only the small strands of ribbon sewed to his old uniform remain – the tokens of a courageous yet somewhat tragic military career.