INSIDER 29 | SPECIAL FEATURES | Jean Renoir: The Cinema of Life and Art

By Christopher Faulkner

Two questions. What makes Jean Renoir a great filmmaker? What makes his work of the nineteen-thirties pertinent to us today? Both questions admit of the same answer, which is addressed in what follows.

Jean Renoir (1895-1979) says he became a filmmaker to satisfy his first wife, Catherine Hessling (Pierre-Auguste Renoir’s last model), who wanted to be a movie star. His earliest films were financed by the sale of valuable paintings bequeathed him by his father, an action he later came to regret. The eight films he made at the end of the silent film period between 1924 and 1929 were an eclectic mix of melodramas, experimental short subjects, costume dramas, and a comedy. There was little here that showed much promise, and he failed to make his wife a movie star.

All that changed with the nineteen-thirties and the advent of sound to motion pictures. Sound (voice, effects, music) grounded Renoir’s filmmaking in the realism of character and everyday life. Footfalls on a flight of stairs, radio music resonating across a room, voices cascading in conversations on-screen and off, whenever possible Renoir recorded with direct sound, sound which originated from within the story space of the fi lm rather than being recorded in the studio and post-synchronized. Renoir argued that the practice of dubbing actors’ voices was a religious heresy, akin to dividing the body from the soul. Every voice is unique, with its own rhythms of speech, accent, and social definition. Furthermore, when characters are anchored by the space or environment from which they speak, then that space or environment is part of what lends them their identity.

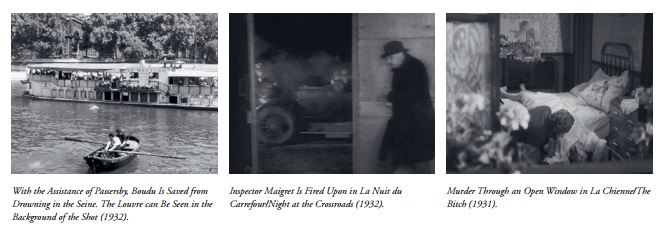

To that end, wherever possible Renoir shot on location rather than in the studio. He favoured long takes and a moving camera. His signature stylistic effect is shots with great depth of field, so that the foreground, middle ground and background may all be equally in focus. This permits a number of actions to take place simultaneously at different planes within the picture space, actions which may conflict with or complement one another. Another characteristic of Renoir’s thirties style is a propensity for shooting through doors and windows to enlarge the playing space, open up a scene, and connect inside and outside so that they become co-extensive. For example, many of Renoir’s films of the thirties feature a murder as their climactic scene and in every instance Renoir has his camera make this private act an affair with public implications. Private and public life are never separate worlds in a Renoir fi lm. There is always the sense that what we see or hear on screen at some particular moment is always part of a larger whole which can be revealed to us at any time by a movement of the camera, a sound off-screen, or a window flung open in the background of the shot. The ways in which Renoir uses sound and image to embed his characters in the environments which define them are an important dimension of what makes his cinema a profoundly social cinema.

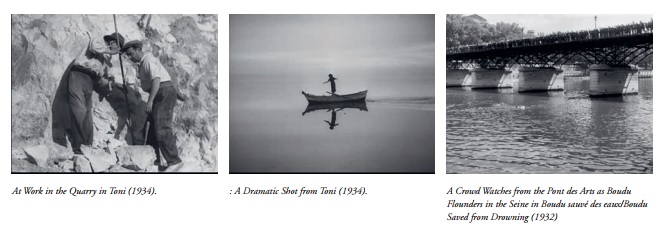

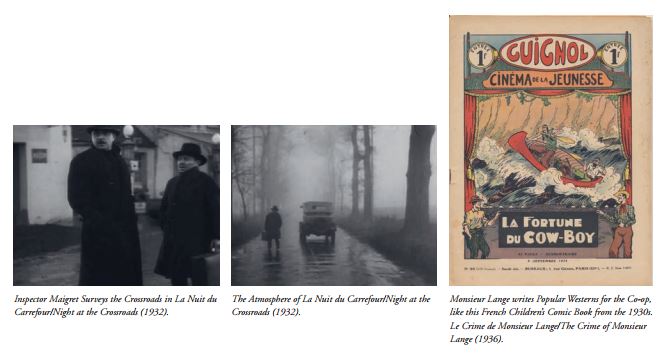

One historian said of the fifteen films which Renoir directed between 1930 and 1939 that they comprise a “social inventory of our time.” Quite properly, this remark makes him the Balzac or Dickens of his era. Renoir’s output in the course of those ten years was remarkable, with many of the films among his greatest achievements and at least two films at the end of the decade widely considered masterpieces in the history of cinema. In La Chienne/The Bitch (1931), which is set in Montmartre, the scene of pleasure and crime, a petit-bourgeois cashier is snared in the sordid web of deception spun by a prostitute and her pimp, until he realizes he has been their gullible prey and is driven to extricate himself through murder. La Nuit du carrefour/Night at the Crossroads (1932), a murky narrative involving a theft of jewels and suspected spies, the first film to be adapted from a Georges Simenon novel with Inspector Maigret, was shot largely at night in rain and fog on location at a crossroads north of Paris. This atmospheric precursor of film noir was followed the same year by Boudu sauvé des eaux/Boudu Saved From Drowning, a wide-awake comedy about a down and out tramp who is taken in by a sympathetic, middle-class Paris bookseller, only to turn around and expose the hypocrisies of bourgeois life and its pretensions to culture.

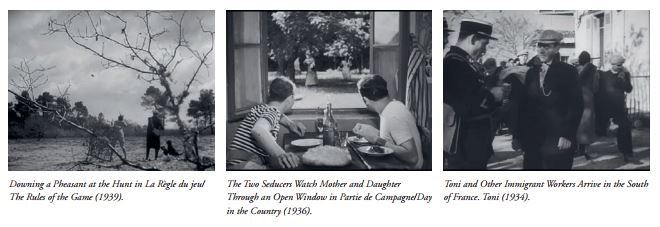

With the support of Marcel Pagnol, Renoir went to the south of France in 1934, where he shot the prescient Toni, a film which deals with the circumstances surrounding a crime of passion among Spanish and Italian immigrant workers in an environment hostile to their culture and way of life. Stylistically, and in its choice of subject matter, Toni anticipated Italian neo-realism of the post-war years. (As it happens, two years later Luchino Visconti would assist Renoir with his minor masterpiece, Partie de campagne/A Day in the Country.) In late 1935, Renoir undertook Le Crime de Monsieur Lange/The Crime of Monsieur Lange, about a co-operative which is set up by a company of typesetters after the flight of their owner, who is a sexual and financial predator. When the owner unexpectedly returns, he is shot by the day-dreaming Monsieur Lange who writes the popular stories – like the film we are watching – which the co-operative now prints. Lange’s action presumably saves the co-operative while ridding the world of an unscrupulous capitalist. The Paris courtyard setting of this film becomes metaphor and metonymy for the whole of French society.

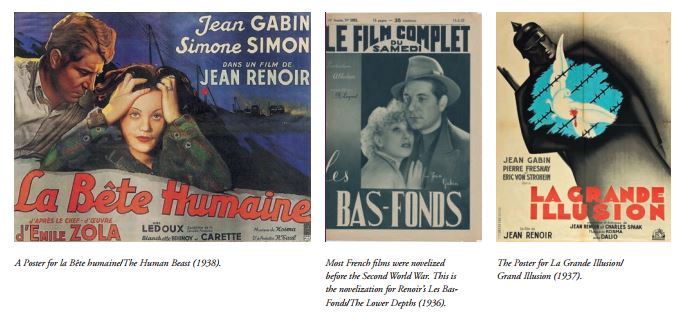

In the context of an increasingly divisive nineteen-thirties, both nationally and internationally, films such as Toni and Le Crime de Monsieur Lange suited the interests of the political left and Renoir worked to espouse its causes. More particularly, he loaned his support to the French Communist Party for whom he wrote articles, a regular newspaper column, gave speeches, and in the spring of 1936 directed La Vie est à nous/Life Is Ours, which was made to help the party in the 1936 elections and shown at party rallies. While continuing his support for the Popular Front coalition which came to power in June 1936 on behalf of the rights of the working class and in opposition to the rise of Fascism, Renoir made La Grande Illusion/Grand Illusion in the winter of 1936-37. Renoir’s most popular film to this day, it received world-wide attention from the moment of its release. Set during the First World War (although we see nothing of the fighting), it exposed the futility of war. Against the threat posed by the renewed militarism of Nazi Germany, its pacifist message was extremely powerful. In the (newly?) militarised world of today, we can still understand the power of that message.

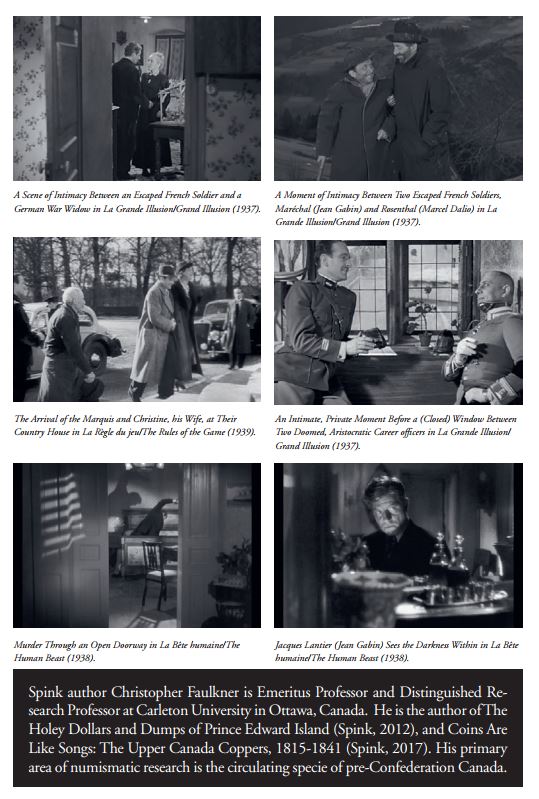

But the strength and beauty of the film cannot be reduced to its “message.” It displays all those characteristics of style with sound and image mentioned above, and it also features extraordinary performances from its actors who embody their characters with an incomparable rightness of gesture and accent. Further, La Grande Illusion is a war film that is also a love story or, in truth, a number of love stories. There is the story of the (hopelessly idyllic) relationship at the mountain farm near film’s end between the escaped French prisoner, Maréchal, and the German war widow, Elsa, neither of whom speaks the other’s language. There is the story of the equally tender relationship between Maréchal (played by the great Jean Gabin), a working-class mechanic, and his fellow escapee, Rosenthal, an upper middle-class French Jew. In the prison from which they have escaped, we are witness to the powerful bond between two aristocrats, one a French prisoner, the other his gaoler. They belong to a world of privilege and prejudice which is being left behind, the film says, in favour of a world which bridges class differences, crosses national and linguistic barriers, and overcomes dangerous prejudices such as anti-Semitism. The film’s success in conveying the deeply felt nature of the relationships between its characters encourages us to believe that this is our future too.

In the fall of 1938, Renoir directed another international success, La Bête humaine/The Human Beast, adapted from the novel by Emile Zola. Set among railway workers, this film stars Jean Gabin as Jacques Lantier, a train engineer who witnesses a murder in a passenger compartment but keeps quiet so as not to implicate the wife of the murderer, a classic femme fatale with whom he has fallen in love. When urged to kill her husband, he cannot do so, but in a fit of madness kills her instead, and then commits suicide by jumping from his engine as it hurtles down the track. During the making of the film, Renoir wrote a number of articles in support of the railway workers and their union, but the film is a dark, unsettling tale which is less about the rights of workers and more about masculine obsession, its ties to the technologies of power (embodied by the railroad), and sexual violence against women. Once again, a film which may seem to belong to its moment can also speak to us in our present moment with chilling insight.

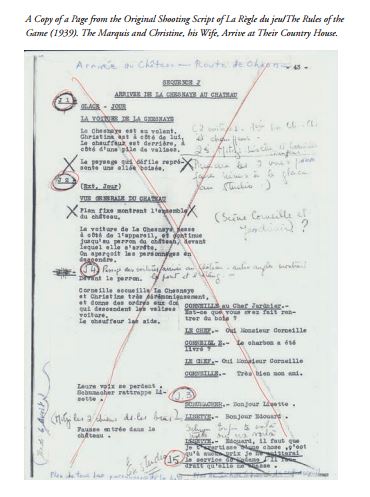

Renoir’s undoubted masterpiece is La Règle du jeu/The Rules of the Game, the film which crowned his thirties career. In its ten-year critics’ polls from 1962 to 2002, Sight and Sound ranked La Règle du jeu as either the second or third greatest film in the entire history of world cinema. In 2012 it ranked fourth. The film has been greatly admired by other filmmakers, from Orson Welles, through François Truffaut, to Robert Altman, and it has been much borrowed from, virtually plagiarized (“the sincerest form of flattery”) with respect to themes, plots, situations, character types, stylistics, and much else besides in films such as The Shooting Party (1984) and Gosford Park (2001), among others. Something of the film’s reputation arises from the fact that it was released on July 7, 1939, less than two months before the outbreak of the Second World War, a war everyone knew was inevitable. Although it makes no mention of the war, La Règle du jeu is a brilliant account of French society “dancing on a volcano” (to quote Renoir himself).

La Règle du jeu is both a comedy of manners and a murder mystery (in this case the question is not ‘whodunnit’, but why it was done at all). The characters represent the haute bourgeoisie of French society and their servants, led by a minor aristocrat who is Jewish. The film draws on that hoary staple of both comedies of manners and murder mysteries, the country house, to which it takes its characters to play out their fates. There are upstairs and downstairs intrigues, a masked entertainment, mistaken identities, a shooting party (a massacre of the innocents) and, in its conclusion, a murder which is framed as an accident. La Règle du jeu is a film of great complexity because, impossible as it may seem, the death at the film’s end is both a murder and an accident. As though to emphasize the intractable situation of a society in crisis, this is but one among many irresolvable contradictions in the film. Truth and falsehood, reality and illusion, theatre and life are presented not so much as either/or contrasts but as both/and paradoxes. Certainty of meaning is indeterminate, unstable. Renoir has suspended the hopes for social transformation to which he had committed himself earlier in the nineteen-thirties. What the film shows us instead is a society closed in upon itself, defensive, hypocritical, cynical, and willing to do anything to preserve its way of life. This is, as it were, the last gasp of a society unwittingly bent on self-destruction. At the same time, there are characters in this society who are charming, generous, and intolerant of xenophobia and anti-Semitism. (La Règle du jeu and La Grande Illusion are the only two pre-war French films made after 1936 which feature a major Jewish character played by a Jewish actor – the delightful Marcel Dalio). Audiences found La Règle du jeu difficult because of its mix of genres, because of its shifts of tone from witty comedy to slapstick farce to tragedy, because it is an ensemble film with eight important characters instead of a single protagonist, and because it is stylistically demanding, with Renoir having reached the peak of sophistication in his use of sound and image. It demands its audience’s sharp attention, but the reward is the pleasure and intelligence that comes with a masterwork on the order of a Mozart opera.

Curiously, the more time passes so increasingly Renoir’s films of the nineteen-thirties come to seem like documents of everyday life. That’s not what we usually say of fiction films, and of most such films it cannot be said. In a period in which Hollywood and Europe confined most of their production work to the studio, Renoir was one of the few Euro-American filmmakers of the nineteen-thirties who took his work into the streets. His films are thickly textured with the density of the quotidian, with the ebb and flow of people, places, things, ideas and feelings. However, to say that Renoir’s films may be documents is not to say that they are documentary films. As they breathe the life of their particular moment in time, its great events and its minutiae, they body it forth into a living narrative, a moving picture. By unfolding the personal and social lives of his characters in a fictional narrative, Renoir is able to give his films that depth of feeling which lets them speak to us today.

No matter when a film was made, what one values about it is always contemporary with the moment at which one experiences it (or writes about it). We only make meaning out of movies in the context of our everyday existences. Fortunately, because most of Renoir’s films are readily available on DVD, with English subtitles, and superior sound and image quality, we can each test that assertion at our leisure.