INSIDER 29 | SPECIAL FEATURES | Ninfa, Caetani and Coins

By Esme Howard

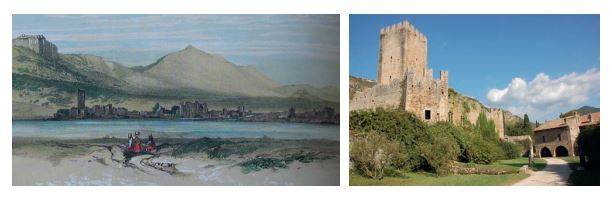

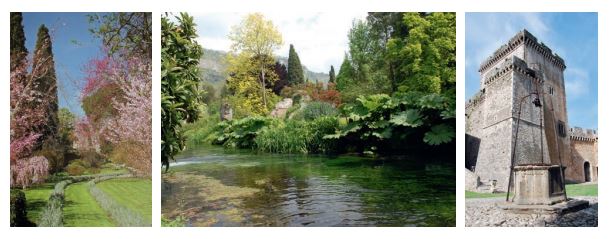

The romantic garden of Ninfa, just 65 miles south of Rome, was created by the Caetani family almost one hundred years ago, and lies among the eloquent ruins of a small but affluent medieval town, which in turn grew out of Roman and papal settlements, and passed to the Caetani in the early fourteenth century. Their family history marks every stretch of the Tyrrhenian coastland – from Pisa, Rome, Cisterna, Ninfa, and Sermoneta and on down to Fondi, Gaeta and Naples. In the family history Domus Caietana, the ninth-century Anatolio, Lord of Gaeta, is the first of the Caetani to gain regional prominence. By the thirteenth century, the Caetani were a powerful Latium dynasty, with two family popes, several cardinals and considerable military prowess. They held sway over the entire Pontine region to the south of Rome.

The history of Ninfa is therefore almost a history in coins; whether in display cabinets or lying deep in the pockets of the ordinary man, coins have spoken in the course of history of the power and authority of sovereigns, emperors, popes, anti-popes and even a minor cardinal here or there. Most civilisations have been affected by the actions of those entitled to be ‘minted’, so to speak, or by the volatility of their coinage in terms of economic value. The medieval relationship between empire and papacy in the minting of coins, indeed in the exercise of power, was often fraught, and few of Italy’s dynastic families can have been more affected by that relationship than the Caetani, who were never far removed from the actions of those whose heads appeared on the portrait coins of their times.

Pliny the Younger, writing in the first century, records the existence of a small Roman temple dedicated to the water nymphs, close to an abundant spring at the foot of the Lepini hills. By the end of the Roman Empire, with the Appian Way in disrepair and repeatedly flooded by the famous Pontine marshes, the stretch between Cisterna and Monte Circeo was abandoned and ‘re-sited’ inland, a few meters above sea level, at the foot of the Monti Lepini and passing close to those alluring spring waters. A settlement inevitably grew up there, travellers rested, watered their horses, and paid a toll. The spring waters were dammed and harnessed for milling and other purposes. Ninfa ceased to be an imperial possession in the eighth century, when the Holy Roman Emperor Constantine V (718–775) made a gift of it to Pope Zacharias (741-752), one of the earliest popes in whose honour a coin was minted.

The little town grew in size and in commercial importance. Mirroring Rome, seven churches were built, the most imposing of which was Santa Maria Maggiore, whose ruins date from the tenth century and are imposing to this day. Holy Roman emperors were often at odds with the papacy, the Holy See being twice occupied by the Caetani. In 1118, Giovanni da Gaeta succeeded Paschal II to become Pope Gelasius II. Persecuted by Emperor Henry V (1086–1125), whom he fruitlessly excommunicated, Gelasius lasted just one year as pope, dying in exile in 1119. In 1159, the elected pope, Alexander III (c. 1100–1181), escaping from the Roman supporters of Emperor Frederick I’s anti-pope Victor IV, took refuge in Ninfa where he was formally consecrated on 20 September 1159 in Santa Maria Maggiore. Frederick, or Barbarossa as he was known (1122–1190), took his revenge and wrecked the town, but it rose up again, adding further to its fortifications. Alexander died in 1181.

Caetani history gives way now to Benedetto Gaetani (1235–1303), whose family had settled in Anagni, between Gaeta and Rome. In 1294, succeeding the hermitic St. Celestine V, he was elected pope and took the now notorious name of Boniface VIII. A competent canon lawyer and patron of the arts, he founded the Rome University of La Sapienza and renewed the Vatican Library. His pontificate, however, was mired by constant disputes with Philip IV of France (1269–1314).