INSIDER 29 | SPECIAL FEATURES | Some British Awards for the Peninsular War, 1808-14

By Peter Duckers

Between 1808 and 1814 - a period of time as long as the Second World War - British armies in association with their Portuguese and Spanish allies fought an almost continuous series of campaigns in the Iberian peninsula. Some of their sieges and battles, like Talavera, Badajoz, Albuhera and Salamanca, have gone down in British military history as amongst the greatest of victories; at least one - the battle of Vittoria in June 1813 - had Europe-wide repercussions, such was its military and political significance. The Duke of Wellington’s triumph in the battle, in which the French occupation forces of King Joseph Bonaparte were comprehensively defeated, demonstrated forcibly that Napoleon’s power in Europe, already shaken by the disastrous Russian campaign of 1812, was perhaps coming to an end. The victory was celebrated as far away as St. Petersburg and in Vienna Beethoven was moved to compose his “Wellington’s Victory or the Battle of Vittoria”. As a direct result, the Austrians declared war on France and both the Emperors of Russia and Austria offered Wellington command of their armies - which he declined.

Yet is seems remarkable that for all their battles, engagements, sieges and defences, British soldiers received no official medals for the fighting or for their gallantry or meritorious service. Quite simply, there was at that time no nationally established system of awarding campaign medals per se - although the East India Company had begun the general process of giving such awards to its Indian soldiers over twenty years earlier.

It is quite clear that this lack of rewards in the face of a major war caused concern in some quarters, since one of the medallic features of the Peninsular War period is the sudden appearance of regimental medals. These were instituted under the auspices of a commanding officer, a group of officers or other individuals as rewards for their own soldiers, recognising gallantry in action or meritorious service or simply participation in a notable regimental action. By no means all regiments or units produced these awards, but some that did created attractive and highly-regarded medals (then and now) which, if they are named to the recipient, offer a distinctive and interesting possibility of research.

The only “campaign” awards produced at the time were the very elegant and distinctive gold crosses and medals granted to officers. The first example, perhaps establishing a precedence, came in 1806 in the form of the Gold Medal awarded by order of the Commander in Chief, the Duke of York, to 17 officers for their service at the battle of Maida in Calabria. This featured on its obverse the profile and titles of Prince George as Regent, while its reverse bore the name of the battle and a bellicose Britannia advancing with spear and shield, being crowned with laurel by a “Winged Victory”. For some reason, this design prototype was not continued - the Army Gold Medals eventually established in 1810 were plainer, carrying on the obverse an image of Britannia seated on a globe, proffering a laurel wreath in her right hand, and in her left hand, which rests upon a Union shield leaning against a globe, a palm leaf; at her feet lies the “British lion”. The reverse simply carried the name of the action being commemorated, enclosed within a laurel wreath.

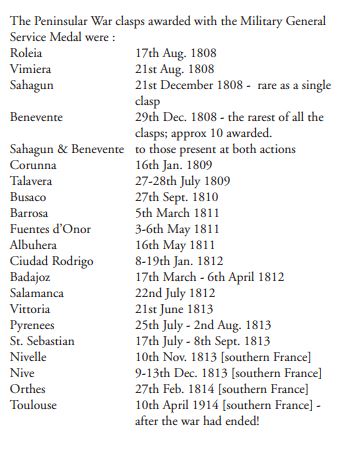

Apart from the distinctive Maida version, there were eventually three types of award - the Large Gold Medal (restricted to General officers), the Small Gold Medal (to lower ranking officers) and the Army Gold Cross. They originate from an Order of 9th of September 1810 which authorized the bestowal of a gold medal on 107 senior officers for their distinguished service at the battles of Roleia and Vimiera (1808), the cavalry actions of Sahagun and Benevente (1808), Corunna and Talavera (1809). The awards were added to (later battles commemorated) as the war progressed.

Both the Army Gold Cross and the Gold Medal were only awarded, with just a few known exceptions, to Field Officers (i.e. those who commanded a unit) or higher-ranking staff officers, such as Divisional or Brigade commanders. They really represent rewards for distinguished service in command “under fire”, rather than being specifically gallantry or general service medals - though undoubtedly many recipients did display gallantry in the relevant action.

It was originally intended to give a separate gold medal for each action to which the recipient became entitled (i.e. one officer could wear more than one medal) but in 1813 it was announced that gold clasps would be awarded to the original medal, just carrying the name of the battle. Each medal was enclosed in glass lunettes whose frame bore the name of the recipient engraved on its rim. They were worn from what became known as “the Military Ribbon of Great Britain” - dark red with narrow blue edges; the Army Gold Crosses and Large Gold Medals were worn around the neck and the Small Gold Medal on the breast. They were awarded with extra clasps, as earned, these taking the form of chunky gold bars simple bearing the name of the action within a decorative foliage surround. The Gold Cross was awarded to officers who already possessed the Gold Medal with two clasps (i.e. rewards for three actions); the Cross then showed on its obverse arms the names of the initial three actions and the fourth for which the Cross became the reward. The reverse was the same. It too could be awarded with extra clasps, if earned - the Duke of Wellington’s carried no fewer than 9 extra clasps (i.e. representing 13 awards) and can now be seen at his residence, Apsley House, in London.

In all, only 165 Crosses and clasps, 88 Large Medals and clasps, and 596 Small Medals and clasps were awarded. The medals ceased to be conferred after the re-organisation of the Order of the Bath in January 1815 to create a new lower tier, the grade of “Companion” (CB), to which military officers could be admitted for distinguished service - “to the end that those Officers who have had the opportunities of signalising themselves by eminent services during the late war may share in the honours of the said Order”.

The “Other Ranks” of the British army had to wait more than a generation before they too were awarded an official medal for their previous service. By the mid 1840s, general campaign medals were at last beginning to be awarded (e.g. for China and Afghanistan) and while “the Great War” - as the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars were once known - faded into the past and into the realms of nostalgia, there was a growing public awareness that the surviving veterans had nothing to show for their often arduous service so many years ago. Under the auspices of the Duke of Richmond, a public and press campaign to grant a medal to surviving veterans finally bore fruit. What became known as The Military General Service Medal was authorized by a General Order of 1st June, 1847 and, once rolls had been laboriously compiled, issued in 1848. Many clasp claims by individuals were denied on investigation and many more must have gone unclaimed by old men who simply could not recall where they had served!

The medal rewarded participation in a large number of military actions between 1793- 1814, encompassing service in the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars and the Anglo-American War of 1812. Of the 29 clasps eventually authorised, the majority (21) were granted for the battles of the Peninsular War, with others conferred for service in Egypt (in 1801), at Maida in Italy in 1806, on the Canadian frontier 1812-14, in the West Indies (Guadeloupe 1809 and Martinique 1810) and even the far east (Java 1811). Each recipient would receive the medal with one or more battle clasps to commemorate his presence in a particular action. Remarkably, up to 15 clasps are known to one medal (2 known from the rolls), while 12 men qualified for fourteen clasps and 44 for 13 clasps; 10 or more clasps would be considered rare, whilst medals with 4-9 clasps are frequently seen. The medal, like the earlier officers’ gold awards and the Waterloo Medal of 1815, was worn from “the Military Ribbon of Great Britain”.

It was observed at the time that many significant Peninsular actions were not included - e.g. the sizeable battles at Arroyos-dosMolinos, El Bodon or Almaraz, to name but a few - and that the majority represented actions at which the Duke of Wellington commanded. This is not strictly true; at Barrosa near Cadiz in 1811, Lt. General Thomas Graham was in command, while at Albuhera in 1811, it was Lord Beresford. But there may have been some truth in the observation that Wellington dominated - it is interesting that the medal itself bears on its reverse the figure of Queen Victoria (who was not born at the time of any of the actions!) crowning with a laurel wreath a kneeling figure of the Duke of Wellington. In general, Wellington did not agree with the award of simple campaign medals - he is on record as stating that soldiers were paid to do their duty!

The medal was awarded only to surviving claimants; next of kin could not apply on behalf of a deceased relative, although the medal was issued to the next of kin of those who had died in the period between application and issue. There were only some 25,650 applications in total and there must have been many old, illiterate or incapacitated veterans who never knew about it or simply never claimed.

Interestingly, those veterans who were not present in one of the designated actions received no award, even though they might have spent years on active service or been wounded or injured on campaign. The idea of giving a medal without clasp to these men does not seem to have occurred.

Nowadays, the Peninsular regimental medals and MGS, with its multiple clasps, are a very popular collecting theme. Whilst examples of the MGS are easily available on the collectors’ market, they can be very expensive if they carry rare clasps (e.g. the single “Sahagun”) or clasps which are rare to a particular regiment or those with 10 or more clasps. Needless to say, all the Gold Medals - Large or Small - and the Army Gold Crosses are very rare and command high prices on the occasions that they do occur in auction.