Auction: CSS41 - The Numismatic Collectors' Series sale

Lot: 331

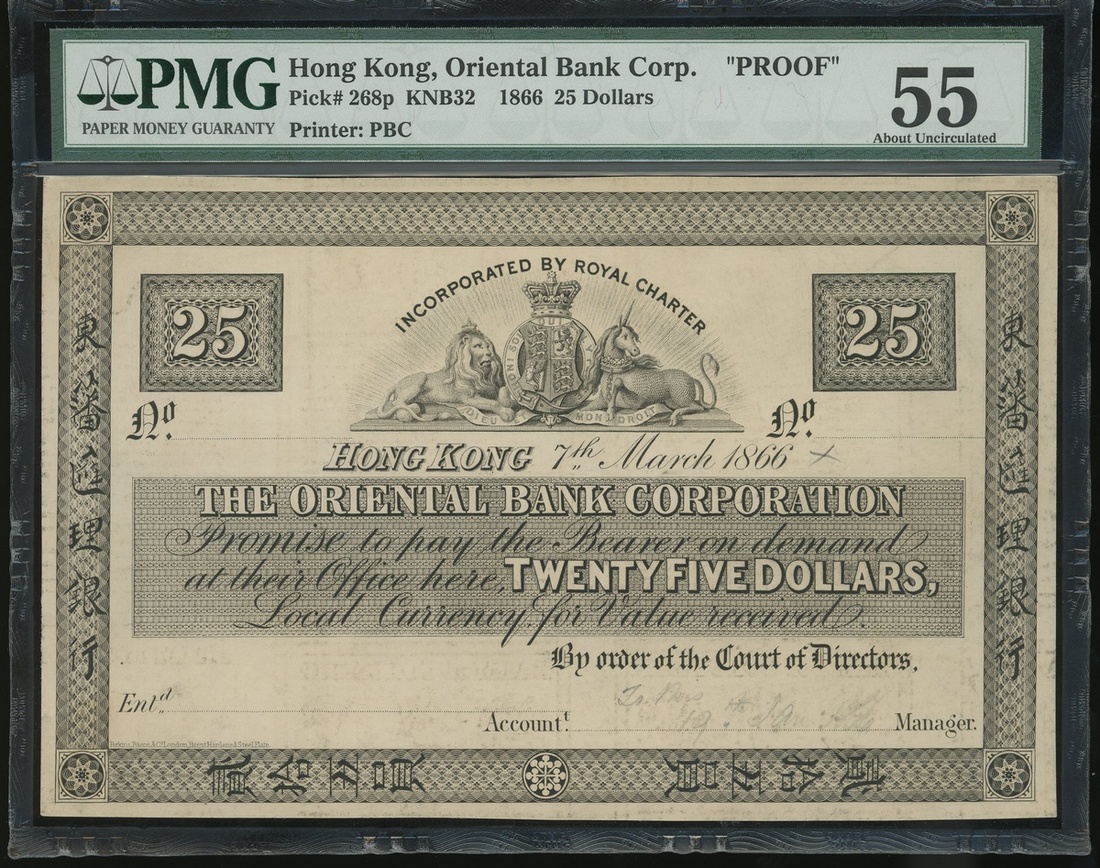

The Oriental Bank Corporation, Hong Kong Office, $25, Hong Kong 7th March 1866, proof on India paper by Perkins, Bacon & Co. With ‘No....’ at left and right under denomination tablets before the serial number spaces, the bank name in Chinese in borders at left and right, the denomination also in Chinese in bottom border to left and right, the inscription at centre including the words ‘At their office here, Twenty Five Dollars, Local Currency for Value received,’ the signature spaces engraved ‘Ent’d...........Account’t...........Manager.’,

(Pick 268p), PMG 55 About Uncirculated (Printer’s Annotations, Previoulsy Mounted). A fabulous note bearing the rarest denomination and from a series that is notorious for being rare. In recent years all available notes from the Oriental Bank are the issued $5’s from 1879 with no other denominations offered. This is a once in a generation opportunity to acquire the Oriental Bank $25.

* From the Archives of Perkins Bacon & Co. London (1935).

* Inscribed ‘To this 19 Jan.66’ by the printer in pencil in the space for the Manager’s signature, and with an ‘x’ in pencil beside ‘1866’, apparently signifying that the date was altered (from ‘1864’?).

* Of the highest rarity, believed to be one of only two examples printed.

* From the Spink/Christie Hong Kong sale of 29 November 1994 (Lot 72), where it brought HKD $308,000 (US$39,740).

* The Oriental Bank Corporation in this period issued notes in denominations of $5, $25, $50 and $100 in Hong Kong, of which the $25 is considered the most desirable, and -- for all banks -- is much the rarest denomination. The $10 was only to be issued fifteen years later, just prior to the Bank’s failure.

* Only five issued Hong Kong Oriental Bank notes are known to exist, two of which are in the Hong Kong Museum of History and the other three -- all $5 -- reside in private collections.

Perkins Bacon & Company were from 1817 the world’s foremost banknote printer, essentially inventing steel plate engraving, and in doing so revolutionizing the printing of banknotes. Unlike other printers such as the American Bank Note Company, which kept “specimen” sheets of each note ordered, Perkins Bacon maintained a policy of printing the absolute minimum, i.e. essentially one proof and no “specimens” -- apart of course from the quantity of currency notes ordered by the client.

Accordingly Perkins Bacon’s archives, much of which fortuitously survived until the 1970’s -- despite Blitz (bombing) damage during World War II -- clearly illustrate Perkins’s procedures.

When a new note was ordered, a plate would be engraved through Jacob Perkins’s patented process. If the plate was satisfactory a single proof note would be “pulled”. This note would normally bear the printer’s pencil inscription “To this” and the actual date, indicating that on this date the plate was accepted, and that the currency order should be printed to the design of the proof.

This unique proof would be glued on four corners and mounted in a record volume, apparently chronologically rather than by any other criteria.

If no further revision was subsequently required to the plate then the single proof pulled on the first day would be the only record kept, and thus absolutely unique.

However, should another order be received and alterations to the plate be required, a second proof would be pulled from the plate. On this proof a pencil ‘x’ would be marked in the vicinity of the feature to be altered. For example the ‘x’ might be over the date or part of the date; it might be over the title of one of the signatories to indicate a change of title; it might be over the last word of the Bank’s name, for example when ......Bank became ......Bank Corporation, an ‘x’ would normally have been marked at the end of the original Bank’s name.

The words “From this” would be added in pencil, indicating that changes were to be made to the plate.

The engravers would then alter the plate to produce the desired current wording, and on satisfaction a proof of the (by now) modified plate would be pulled. This proof would be marked in pencil “To this” together with the date, and the process would repeat itself. The modified plate proof would be dabbed with glue on the four corners and mounted in the record book.

Accordingly every plate would normally have a “To this” proof and possibly also a “From this” proof which would also have been kept. This meant that each Perkins plate would have had at least a single proof note in existence, and possibly a second proof note with the “From this” marking in existence as well.

Remarkably, special instructions were provided by clients as to how even this unique (or one of two) proof was to be preserved:

a) the client might have given permission for a full proof to be kept by the printer;

b) the client may have instructed that the signature area on each proof be cut out for security;

c) the client may have ordered that each proof have the bottom section cut off for security;

d) in some cases such as with the British Linen Bank of Scotland instructions were given not only for the bottom be removed for security but also the top, leaving only with strip with the middle design, this considered enough to show the important data relating to the note and any changes.

That these notes were cancelled or made secure in this fashion at the time of printing is simple to verify: merely turn the proof over. It can be seen that no matter whether the full proof survives, or a cut-signature proof or a proof with the bottom cut off, or a proof with the top and bottom cut off, each would show the four glue marks on the back of that proof!

Thus some Perkins notes are only known by the centre section of the note.

As the vast majority of Perkins clients remained solvent and the notes were ultimately fully redeemed and paid, in the great majority of cases the proof that survived in whatever form may be the only “proof” we have today that a note was actually printed and presumably issued.

Thus while American Bank Note Company for example kept two full sheets of every new note ordered, or of every subsequent order, and British printers Bradbury Wilkinson and Waterlow & Sons prepared sample books of proofs and specimens for presentation or to illustrate their current work, Perkins maintained a strict system for minimizing the number of proofs prepared. This avoided the possibility a proof note might be stolen and somehow fraudulently placed into circulation (enormously irritating the client!).

This $25 is the only note of this denomination certified by PMG.

Historical records made available to Spink China show circulation figures for the Oriental Bank Corporation. At the time of the issue of this note in 1866 the Bank’s circulation ran to slightly less than $1 million. However, with the great banking crash during the summer of 1866, its circulation dropped by November to only $156,000.

The last month for which a circulation figure shows for the Oriental was March 1884 when the circulation appears as $848,635. In April no circulation appears! Indeed the Bank while surviving a banking crisis had to reorganize, and became the New Oriental Bank Corporation, which was not permitted to issue notes at Hong Kong.

Sold for

HK$750,000