Auction: 317 - The Collector's Series

Lot: 459

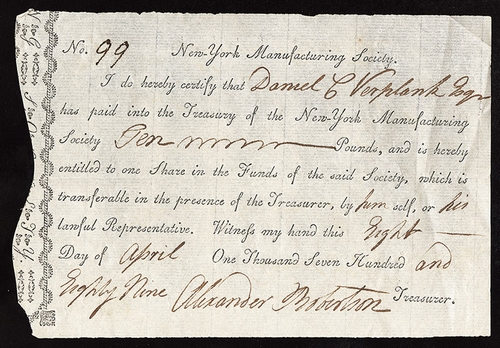

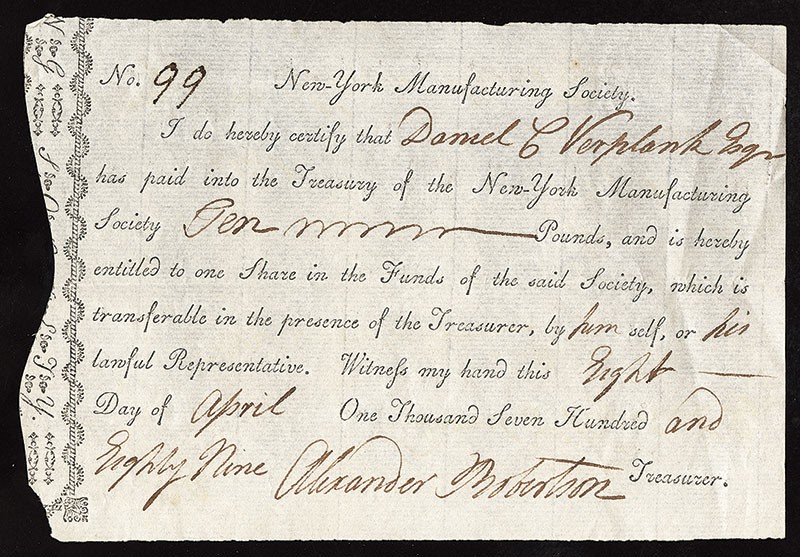

New-York Manufacturing Society. One share. April 8, 1789. No.99. 17cm x 12cm. Ornate counterfoil, left. Issued to Daniel C. Verplank, Esqr. Ornate counterfoil, left, to prevent counterfeiting. Signed by Alexander Robertson, Treasurer. Very Fine. Issued, uncanceled.

The text reads as follows:

"I do hereby certify that Daniel C. Verplanck, Esqr. Has paid into the Treasury of the New-York Manufacturing Society Ten Pounds, and is hereby entitled to one Share in the Funds of the said Society, which is transferable in the presence of the Treasurer, by himself, or his lawful Representative."

Daniel Crommelin Verplanck (1762-1834) was born in New York and lived most of the early part of his life in his family home on Wall Street. He attended Columbia College, and married Elizabeth Johnson, the daughter of the president of Columbia. In 1789, following the death of Elizabeth, he married Ann Walton, and had seven children. They lived on Wall Street until 1803, and then moved to Fishkill-on-Hudson, New York. He represented Dutchess County in Congress from 1803 until 1809.

Note that there is no corporate seal or date of incorporation on this certificate, as no corporations existed under New York law at this time. In the two years following the issuance of this example the New-York Manufacturing Society would be at the very heart of a great political controversy surrounding the granting of corporate charters by states. It is entirely possible that the Society was created by Alexander Hamilton as a test case for that issue.

One reason that no corporations existed in New York in 1789 had to do with the fact that some Americans felt that the Revolution was fought to throw off the yoke of the British corporations that desired to rule the Colonies for profit.

Alexander Hamilton took a different view. He felt strongly that the predominantly agrarian US economy needed to be industrialized. Hamilton argued that the granting of corporate charters was necessary in order to create an atmosphere that would entice investors. He recognized that any firm seeking a corporate charter needed go to the state legislature and prove the company might serve the public good by constructing roads, bridges, and canals, or creating some other public-works projects. Hamilton convinced the politicians that the purpose of the New-York Manufacturing Society was to provide jobs for the indigent, thus serving the public good. That, plus some political maneuvering, accomplished his goal, and a corporate charter was granted in 1791.

Much of the significance of this share certificate revolves around the fact that in 1791 there were exactly two state chartered New York business corporations - the New-York Manufacturing Society, and the Bank of New York, thus the Society was the very first manufacturing entity to receive a New York State corporate charter.

Just what was the New-York Manufacturing Society?

The New-York Manufacturing Society was organized on January 7, 1789, only two months before this certificate was issued. The directors resolved to raise a fund by subscription for the establishment of a woolen factory. Shares were to be £10 each. An article in The Daily Advertiser reported on March 17 that "the amount of the shares already subscribed is Two Thousand One Hundred Pounds." Alexander Hamilton was one of the supporters of the venture.

The Society built a large brick factory on Vesey Street in New York's West Ward, and produced cotton textiles using "Spinning Jennies." The Society hired an Englishman, Samuel Slater, to help them improve their operations. Slater found their equipment "not worth using" and also found the water power sources in

the area inadequate; He moved to Rhode Island Island to work with Almy & Brown, where he established

the first successful water powered textile mill in America.

While the Society failed to yield sufficient profits to its shareholders to remain viable for long, it blazed the way for other manufacturing enterprises to obtain corporate charters.

Museum quality, and perhaps the most significant early American manufacturing certificate. We know of only one other example in public hands.

Sold for

$7,500