Auction: 25002 - Orders, Decorations and Medals

Lot: 214

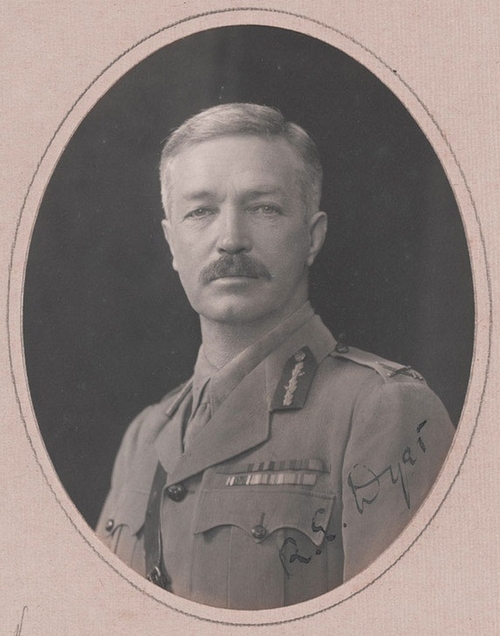

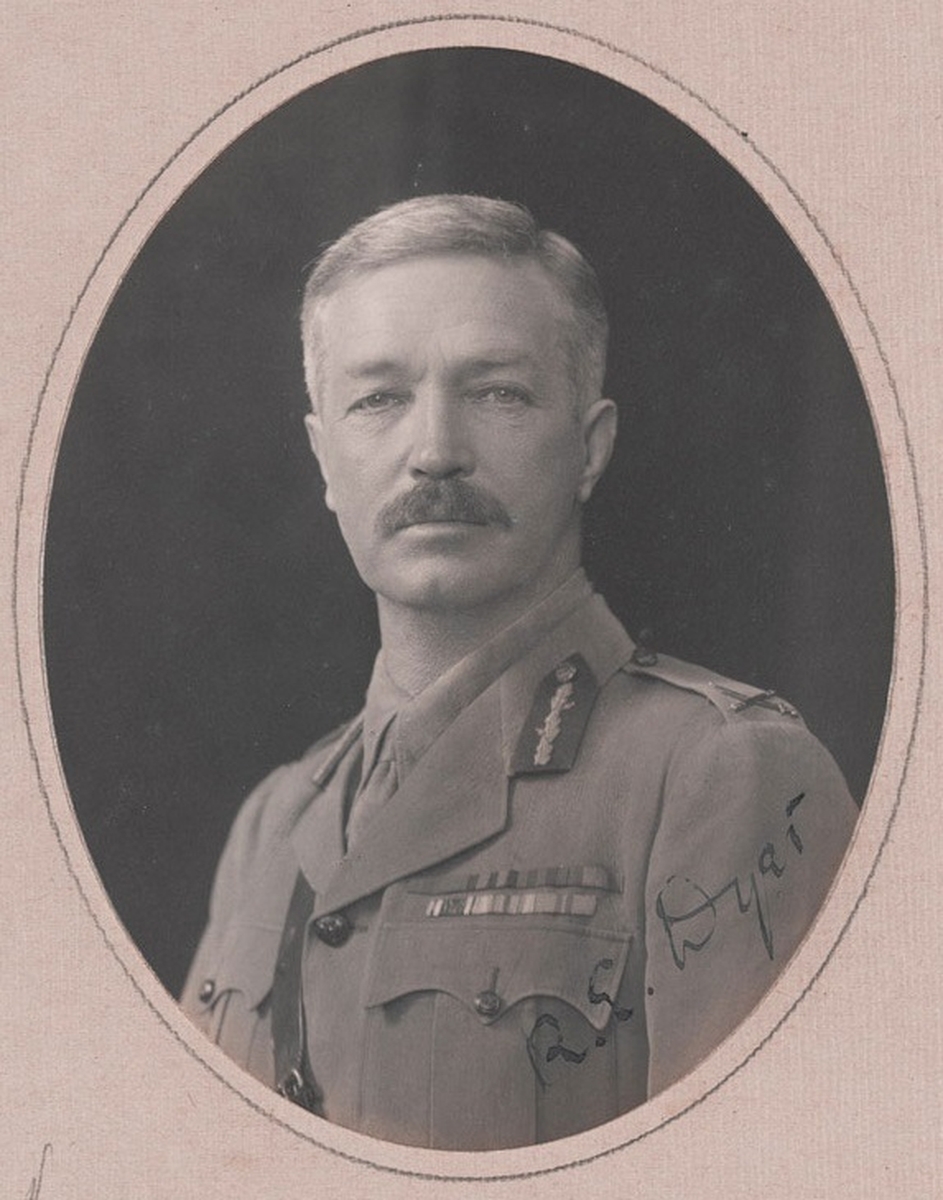

The gold pocket watch presented to Brigadier-General R. E. H. Dyer, C.B., Indian Army, from the 'Dyer Appreciation Fund', following his infamous command in April 1919 at the Amritsar (Jallianwala Bagh) massacre

Gold half hunter pocket watch, by J. W. Benson, Ludgate Hill, London, movement No. 32291, variously marked for 18ct gold throughout, the inner with attractive engraved dedication:

'Brig. Genl. R. E. H. Dyer, C.B. from The Dyer Appreciation Fund in Gratitude for the Courage & Energy by Which he Saved India from Anarchy at Amritsar in 1919', in working condition at time of cataloguing, good very fine and a timepiece of undoubted historical significance

Reginald Edward Harry Dyer was born on 9 October 1864 at Murree in the Punjab, his father being the manager of the Murree Brewery. Educated at Lawrence College Ghora Gali, Murree, Bishop Cotton School in Shimla, before going to Midleton College, County Cork and a brief stint at the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland. The military life was the chosen one for Dyer and he went across to the Royal Military Academy at Sandhurst, being commissioned into The Queen's (Royal West Surrey) Regiment in August 1885. Seeing active service in the Third Burmese War, he transferred to the Bengal Army in 1887.

Dyer would see plenty of action on the frontiers of India and during the Great War commanded Seistan Force, being Temporary Brigadier-General in February 1916.

By early 1919 he was Commandant of the Infantry Brigade in Jalandhar, at the time in which fears of the overthrow of British rule from the local population went into overdrive. Mahatma Gandhi called for a national hartal (strike action) for 30 March (later moved to 6 April), whilst Muslims of India gave its own review of the events on the centenary of the events that followed:

'By April 6, the anti-Rowlatt satyagraha was at its peak in Punjab. "Practically the whole of Lahore was on the streets," historian Hari Singh has recorded. "The immense crowd that passed through Anarkali was estimated to be around 20,000."

The trial and martyrdom of the Ghadar Party leadership in the Lahore Conspiracy trial, and the internment of some 1,500 of the emigrants in India, proved an abiding symbol for a younger generation of radicals. News of young Muslims who had left to fight for the restoration of the Turkish Caliphate (Tehrek-e-Khilafat) but ended up struggling in the ranks of the Red Army during the defence of Kirke, also trickled in. In Punjab, the doubling of prices of wheat, rice and bajra, and the tripling of salt prices fuelled discontent, particularly among artisans and peasants.

In Amritsar, over 5,000 people gathered at Jallianwala Bagh. By April 9, a new spirit seemed to be in the air. Hindu and Muslim protesters drank water from the same glass. British authority appeared to be collapsing. "The Khan Bahadurs and Rai Sahibs are dead," Amritsar Deputy Commissioner Miles Irving wrote, explaining his lack of control over events, "and are not fresh corpses at that."

On April 10 1919, over 15,000 people gathered at the Carriage Bridge. The enraged crowd, armed with lathis, turned on British officials. Four British residents were killed and two were seriously injured; one, missionary Marcella Sherwood, was left for dead. Government property was burned and looted, with persons from the Katra Kanhaiya red light area and members of the Pherna and Safeda communities ("criminal tribes", in colonial nomenclature) joining the revolt.

When Brigadier General Dyer arrived in Amritsar from Jalandhar at 9 p.m. the next day, his fellow British residents had convinced themselves that the events of 1857 were about to repeat themselves. Irving had called Maqbool Mohammad and asked him to inform the city that it was under military occupation.

In Lahore, the uprising had yet to subside. The Danda Fauj (stick-army) of impoverished Muslim artisans led by Chanan Din marched through the streets with sticks and toy guns, declaring their loyalty to the Amir of Afghanistan and the German Kaiser. Crowds of students proclaimed the death of King George, while rumours were spread that Indian troops had mutinied in the Lahore cantonment.

More dangerously for the Raj, the 4,000 Indian railway employees in Lahore went on strike. Even in rural Kasur, which had earned the wrath of Amritsar and Lahore by failing to join the hartal of April 6, huge demonstrations were held. "This is our last chance," local leader Nadir Ali Shah told the gathering. "We must remove the knife around our throat."

On the morning of April 13, Baisakhi day, Dyer's troops marched through Amritsar, proclaiming that all assemblies would be "dispersed by force of arms if necessary." Shortly afterwards, two people walked through the city banging tin cans to announce a rally at 4:30 p.m. at Jallianwala Baug. By afternoon, a peace gathering of over 20,000 people was in place, hearing a succession of speeches condemning the Rowlatt Act and the recent arrests and firings. (Many of those who had gathered at the maidan, however, were villagers, who were on a visit to Amritsar on the occasion of the Baisakhi fair, and were probably unaware of the morning's drama).

No effort, Dyer later admitted, had been made to prevent the gathering from taking place. An aircraft briefly hovered overhead as five speeches were completed before Dyer arrived at Jallianwala Bagh, along with two young officers, Briggs and Anderson, 50 Indian and British rifle-men, 40 Gurkhas, and two armoured cars.

Dyer was convinced that a major insurrection was at hand. He banned all meetings, and hearing a meeting of 15,000 to 20,000 people had assembled he marched his fifty riflemen to a raised bank and a few minutes before sunset, ordered them to shoot at the crowd which included men, women, and children.

The first of 1,650 rounds were fired into the crowd. Dyer kept the firing up for about ten minutes. Bodies were falling all around and no warning was given to disperse before Dyer opened fire. Many died when they jumped into the well at the left-hand side of the maidan, only to be crushed by others who desperately dived on top of them. The wounded cried for help, but there was no aid at hand.

"I fired and continued to fire until the crowd dispersed," Dyer told the official Lord William Hunter Committee of Inquiry set up to probe the violence, "and I consider this is the least amount of firing which would produce the necessary moral and widespread effect it was my duty to produce, if I was to justify my action."

To this day, no one knows how many died. The Punjab Government first asserted that 291 people were killed. An enquiry by Amritsar Deputy Commissioner F. H. Burton later raised the official toll to 379, and some alleged inaccuracies. It is not impossible that the figure could have been higher, given the turmoil and poor communications of the time. Even, casualty number quoted by different sources was more than 1,500, with approximately 1,000 killed.

Mr. Muhammad Ali Jinnah, with another leading Lawyer, C. R. Das proceeded to Lahore to defend the leaders who were being prosecuted. The Governor of Punjab banned their entry in the province. However, after a year on 13 April 1920 a huge meeting was held in Bombay. Mr. Jinnah presided and said that Dyer was a butcher, and the massacre at Amratsar would move even the stones. The great poet Tigore sent a moving message. Mahatma Gandhi moved the Resolution of condemnation.'

In the aftermath, Dyer went on to see further active service on the Afghan North-West Frontier but his career was in tatters. The Committee of Inquiry into the events raged and so did debates in the House of Commons over his actions, besides the shame it had thrown onto the country. Churchill widely condemned the acts and as Secretary of State for War, wanted him to be punished for it. In the events the Army Council superseded by him decided to allow Dyer to resign with no plan for further punishment, something which was upheld by the vote in Parliament on 8 July 1920, with MPs voting by majority of 247 to 37 in favour of the Council.

Nonetheless, there were many who wished to give their support to Dyer. The Morning Post (which later merged with The Telegraph) was fully behind him. It used the following to welcome donations to the fund:

'There are thousands of men and women in England who realise the truth - that the lives of their fellow-country-men in India hung upon the readiness of General Dyer to act as he acted. It is to those men and women that we appeal, to do what is in them to redress the callous and cynical wrong which has been done. General Dyer has been broken.'

Donations swelled and a 'Thirteen Woman Committee' was constituted to present '...the Saviour of the Punjab with the sword of honour and a purse'. Large contributions to the fund were made by civil servants and by British Army and Indian Army officers, although serving members of the military were not allowed to donate to political funds under the King's Regulations (Para. 443). It is said that Rudyard Kipling donated £10. In the end, he was presented with in excess of £26,000, together with the fine gold watch offered for sale today.

The command of Dyer at Amritsar on that infamous day will go down in history, the cataloguer wishes to close with the words of Gandhi, written in a piece on the morals of violence in 1927:

'General Dyer himself surely believed that English men and women were in danger of losing their lives if he did not take the measures he did. We, who know better, call it an act of cruelty and vengeance.

But from General Dyer’s own standpoint, he is justified. Many Hindus sincerely believe that it is a proper thing to kill a man who wants to kill a cow and he will quote scripture for his defence and many other Hindus will be found to justify his action. But strangers who do not accept the sacredness of the cow will hold it to be preposterous to kill a human being for the sake of slaying an animal (sic).'

Subject to 20% VAT on Buyer’s Premium. For more information please view Terms and Conditions for Buyers.

Sold for

£7,500

Starting price

£2500