Auction: 25002 - Orders, Decorations and Medals

Lot: 167

Sold by Order of a Direct Descendant

Peter was killed in action at about noon yesterday, Friday, April 23rd, towards the end of one of the most gallant and courageous actions, led by himself, which I am ever likely to see…

By himself, he & his 25 men put up a most marvellous show, re-establishing the whole position & capturing a lot of prisoners. At this point, I had to come back here to make a report, and it must have been only 5 or 10 minutes after I left that he was killed.

He died fighting, and I am not making an overstatement when I say that the whole Bn, and the Brigadier as well, honour him for his bravery & magnificent effort. His CO has just put him in for a posthumous VC.

Renee, what can I say? It is useless for me to try and express my feelings on paper, as they go far too deep for that. All I know is that I, and we all, have lost one of the finest and bravest of us all, and that he died as he always lived, in the highest interpretation of courage and honour.'

So wrote Lieutenant Edward Deakin on the 24th of April to his sister, Irene, now a widow, on the acts of her late husband, his brother-in-law, Lieutenant Sandys-Clarke.

The unique, important and well-documented Operation Vulcan posthumous Victoria Cross group of five awarded to Lieutenant W. A. Sandys-Clarke, 1st Battalion, The Loyal Regiment (North Lancashire) - the only recipient in that famous regiment in the Second World War of the ultimate award for Valour

Sandys-Clarke hailed from a line of highly decorated soldiers, and could count no less than four relatives as holders of the Victoria Cross

In September 1940 he was severely debilitated after a serious in service motorcycle accident which cost him most of his vision and hearing on the left side; against his surgeon's advice he refused an honourable discharge, but the long and painful recovery also spared him the fate of his 5th Battalion comrades who went 'in the bag' at the Fall of Singapore

Having been twice refused front line service by the Medical Board on account of his grave injuries, he succeeded, on his third and final attempt, in persuading them to let him return to active duty, and potentially a frontline posting

Landed with the 1st Battalion in North Africa in March 1943, he would go into battle in the knowledge that his young wife was expecting their first child

Thrown into the crucible of action during the attack on the important Gueriat-el-Atach feature on 23 April 1943 - that being both Good Friday & St George's Day that year - it was to be a fateful few hours in which he displayed a character of steel, carving his name into the history books

Sandys-Clarke emerged after a fierce German counter-attack, as the sole remaining officer in B Company; he was himself wounded in the head by shell splinters but refusing to be taken to the Regimental Aid Post, he wiped the pouring blood from his eyes and was roughly bandaged with field dressings before gaining approval to form a composite platoon of volunteers to re-capture the important ridge which controlled the line of the advance

Having then, single-handedly, cleared three machine-gun posts and an anti-tank pit, he was killed at the point of victory when stalking and attacking a sniper who had cost his men dearly

Just twenty-three years old, he would never meet his son, who was to be born eight days after the V.C.-winning exploits in which he sacrificed his life

Victoria Cross, the reverse of the suspension bar engraved 'Lt. W. A. S. Clarke (86517). The Loyal Regiment.', the reverse of the Cross engraved '23rd April 1943.', with original investiture pin and in its Hancocks & Co. Ltd., 9 Vigo St, London case of issue; 1939-45 Star; Africa Star, clasp, 1st Army; Defence and War Medals 1939-45, nearly extremely fine (5)

This is the unique award for the Second World War to The Loyal Regiment (North Lancashire).

V.C. London Gazette 29 June 1943:

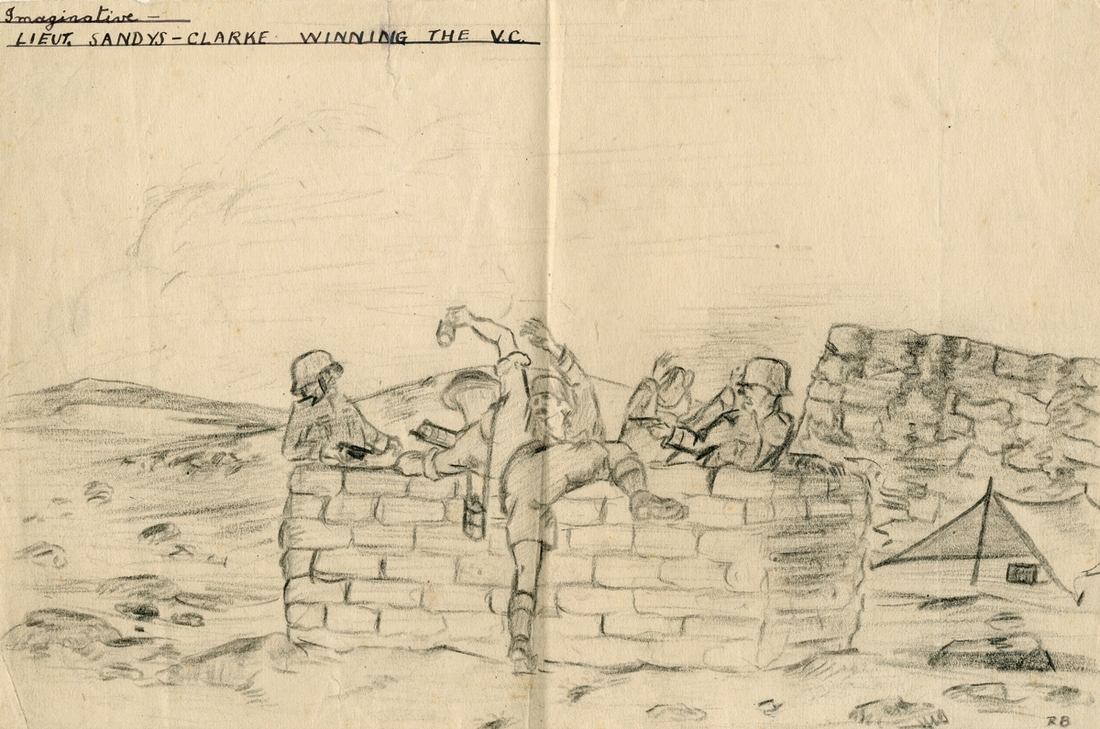

'For most conspicuous gallantry in action at Guiriat El Atach on the 23rd April, 1943. By dawn on that date, during the attack on the Guiriat El Atach feature, Lieutenant Clarke's Battalion had been fully committed.

"B" Company gained their objective but were counter-attacked and almost wiped out. The sole remaining officer was Lieutenant Clarke, who, already wounded in the head, gathered a composite platoon together and volunteered to attack the position again. As the platoon closed on to the objective, it was met by heavy fire from a machine-gun post. Lieutenant Clarke manoeuvred his platoon into position to give covering fire, and then tackled the post single-handed, killing or capturing the crew and knocking out the gun. Almost at once the platoon came under heavy fire from two more machine-gun posts. Lieutenant Clarke again manoeuvred his platoon into position and went forward alone, killed the crews or compelled them to surrender, and put the guns out of action.

This officer then led his platoon on to the objective and ordered it to consolidate. During consolidation, the platoon came under fire from two sniper posts. Without hesitating, Lieutenant Clarke advanced single-handed to clear the opposition, but was killed outright within a few feet of the enemy.

This officer's quick grasp of the situation and his brilliant leadership undoubtedly restored the situation, whilst his outstanding personal bravery and tenacious devotion to duty were an inspiration to his Company and were beyond praise.'

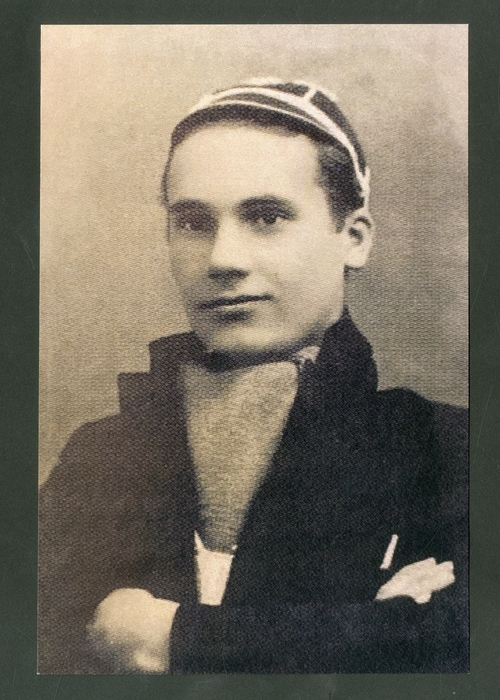

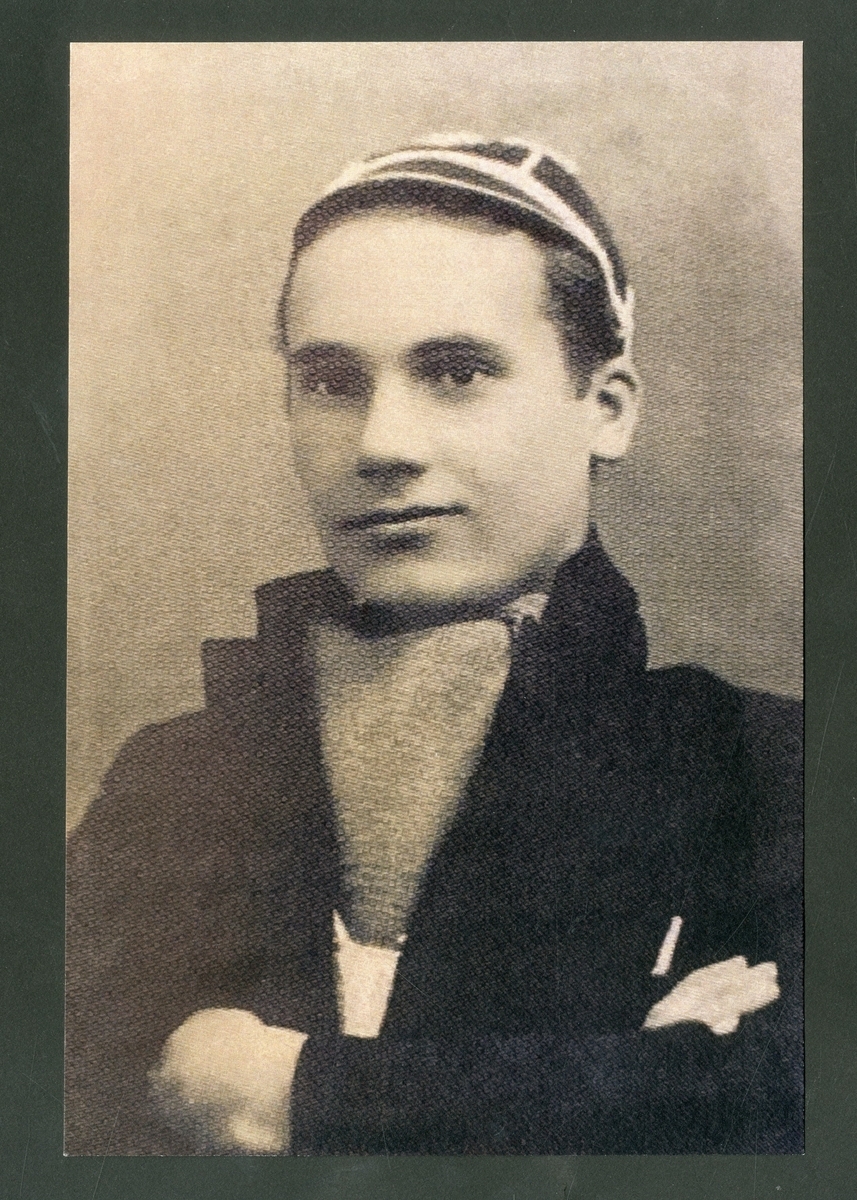

Willward Alexander Sandys-Clarke - who always went as Peter to his family, friends and comrades - was born on 8 June 1919 at Southport, Lancashire, the son of William Edward and Edith Isobel Congreve (née Sandys) Sandys-Clarke. His father was serving in the Royal Naval Air Service and the family lived at Challen Hall, Silverdale, on the North Lancashire coast. The family had a successful cotton mill business.

As so often is the way with the Victoria Cross, it seems gallantry ran through the family, for young Sandys-Clarke could count himself related to no less than four recipients: his maternal grandfather was Colonel Francis Robert Sandys, a cousin of Lord Roberts V.C. (Indian Mutiny, Khudaganj) and General Congreve V.C.(Second Boer War, Colenso), both of whom had sons who each followed their fathers to earn the ultimate award for Valour. Lieutenant The Hon. Frederick Roberts took a posthumous V.C. at Colenso whilst Major Billy Congreve won a posthumous V.C. on the Somme in 1916. The bar was set rather high.

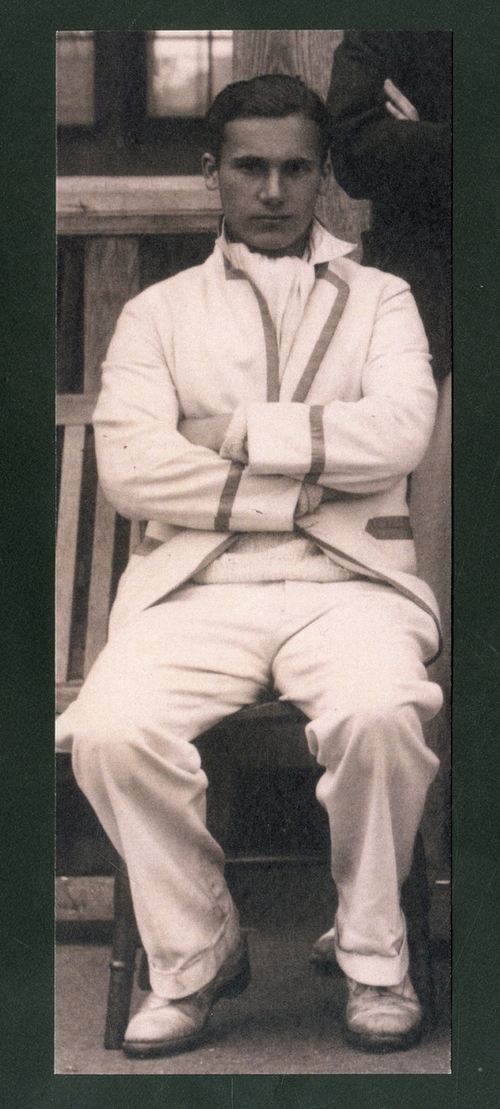

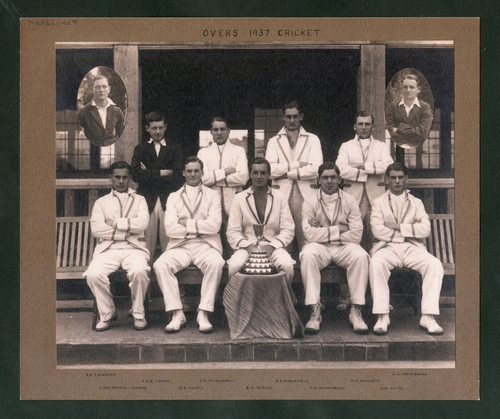

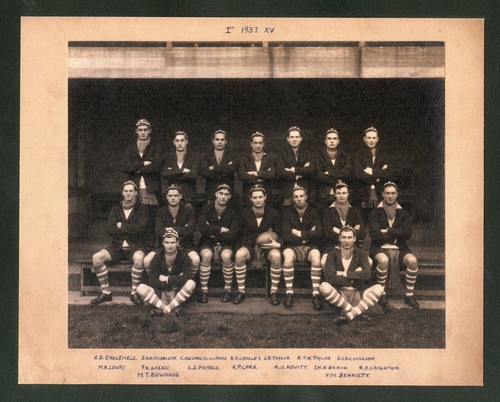

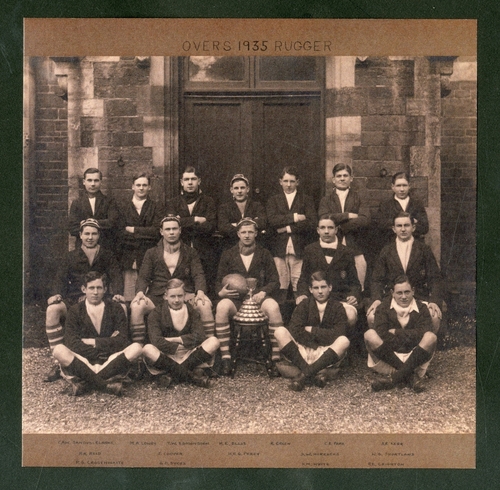

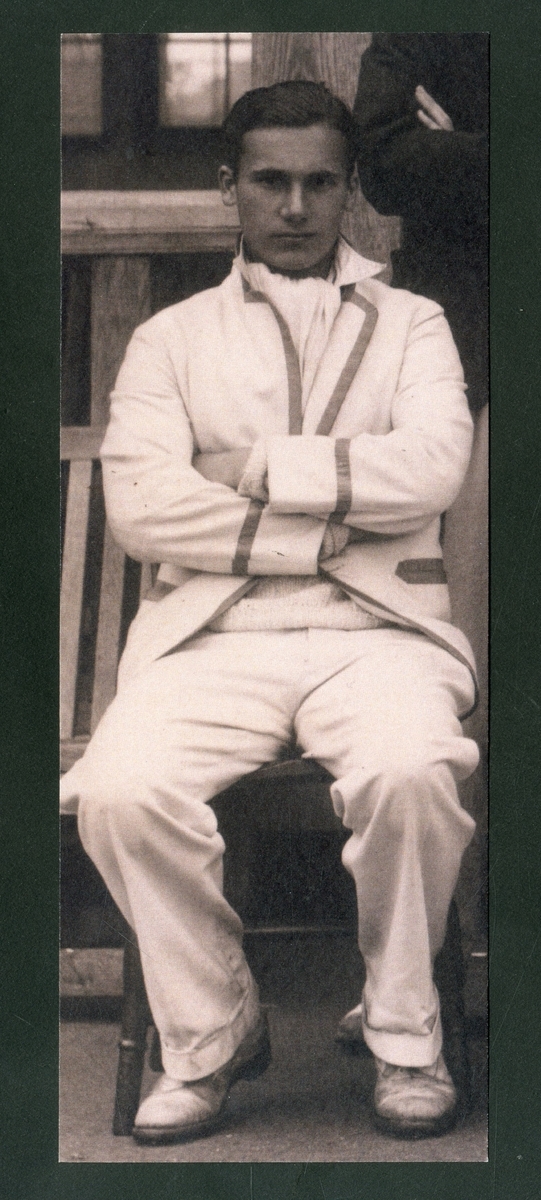

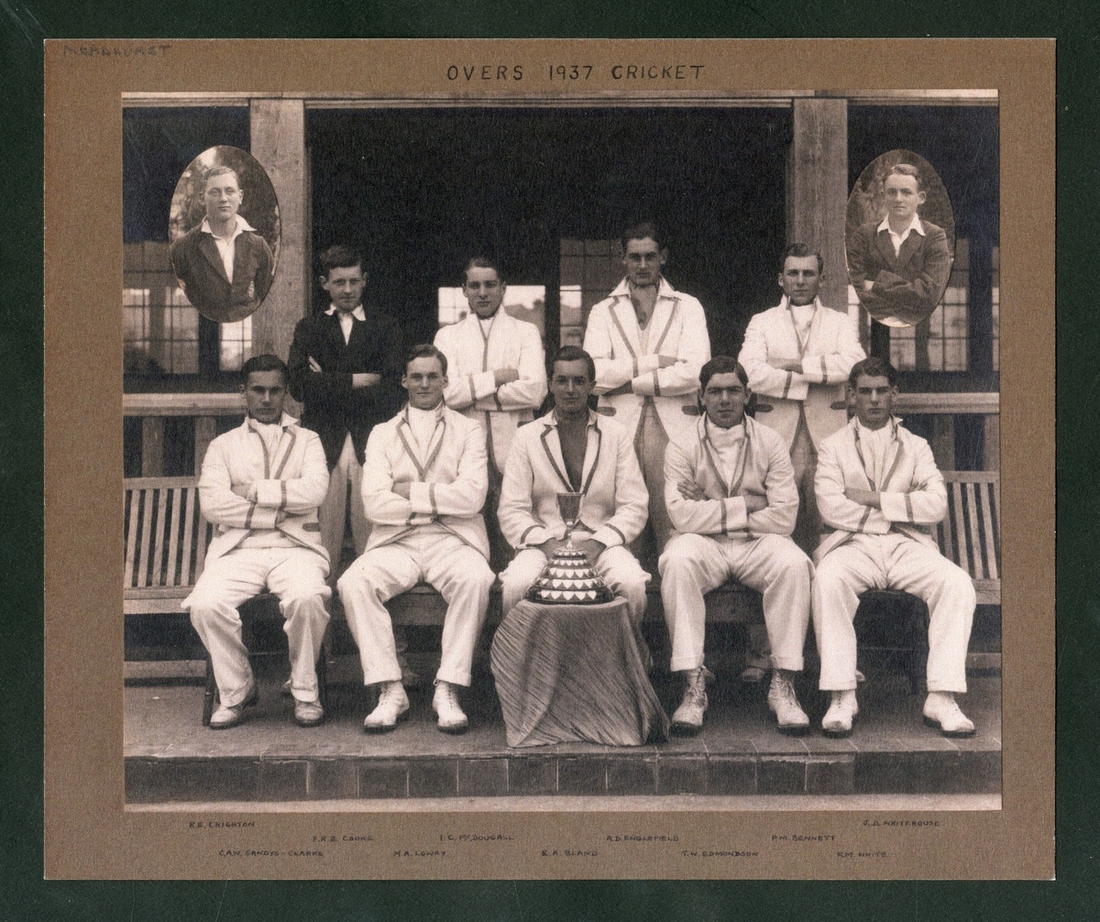

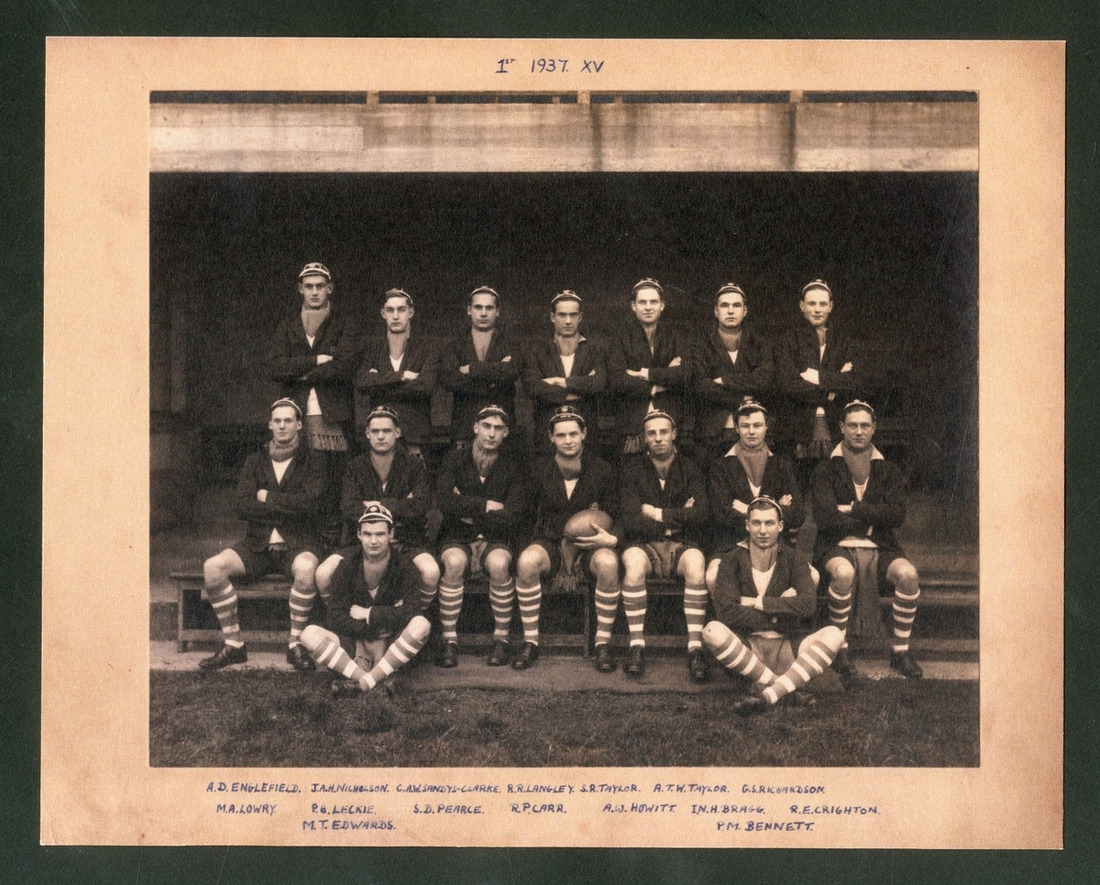

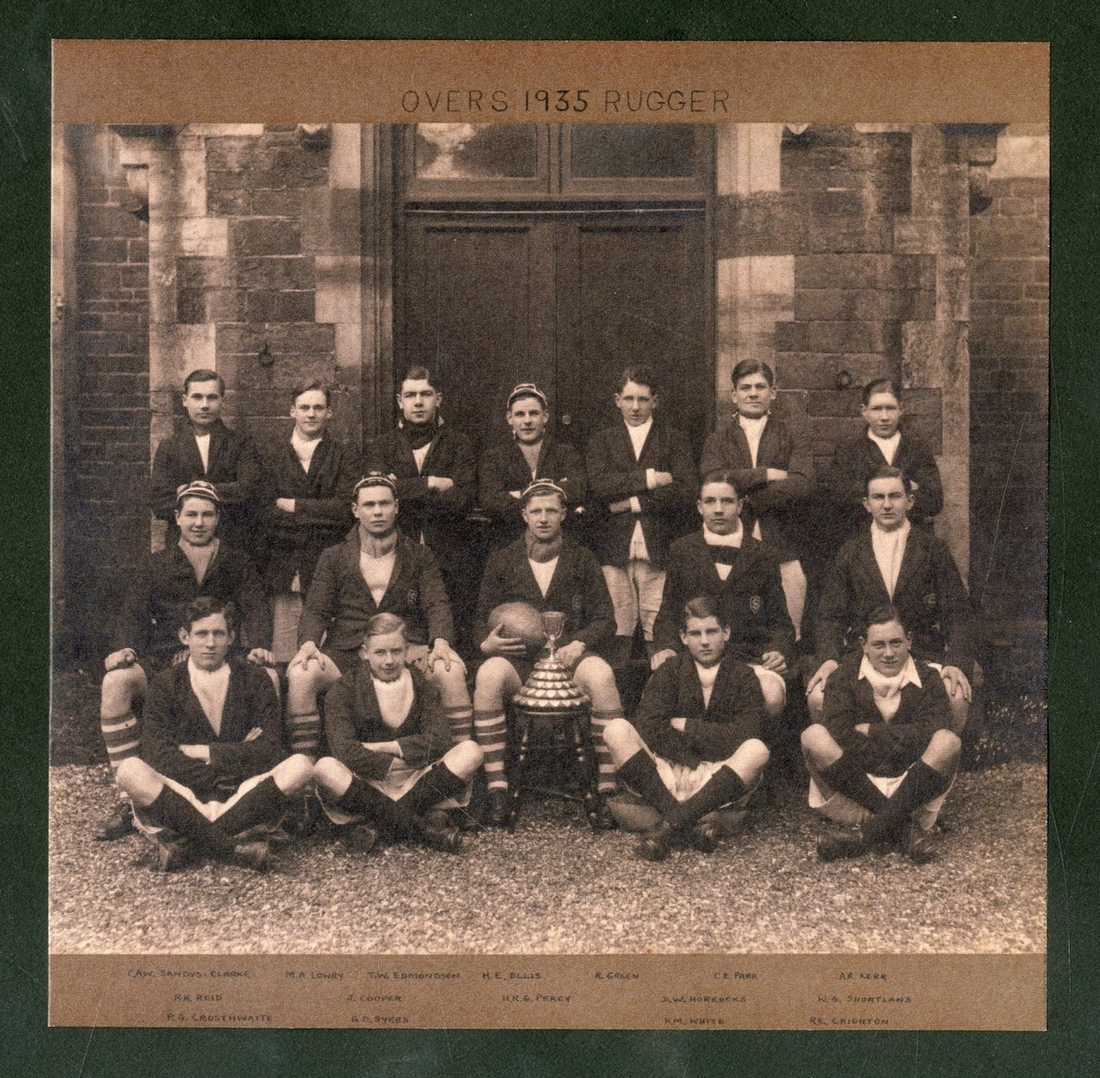

The family moved to Darwen in 1924, and young Sandys-Clarke was educated at Moorland House Prep School and then Uppingham School from September 1933. While at Uppingham, he proved himself a fine sportsman, playing in the Cricket XI, Rugby XV and Fives team - also featuring in a Lords XI with bowling figures of 5-1-7-1 and 4-1-12-1 at the Home of Cricket - leaving in late 1937. Following the death of his mother, along with his father and sister he moved to the home of his grandfather at Harwood Lodge, Turton, near Bolton.

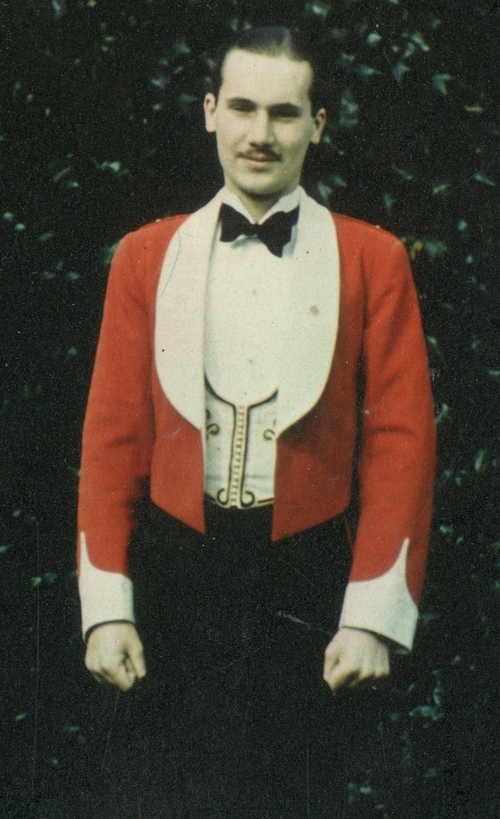

Without much enthusiasm Sandys-Clarke went to work for the family business and also joined the Territorial Army, being proudly commissioned into the 5th Battalion, The Loyal Regiment (North Lancashire) in late 1938.

Sliding doors

With the outbreak of the Second World War, his unit was mobilised and put onto Home Defence duties as they came to strength, being also converted into a motorised reconnaissance unit.

Whilst stationed near Tunbridge Wells in September 1940, Sandys Clarke was involved in a dreadful motorcycle accident. Rushed to the Kent & Sussex hospital, he suffered severe damage to his head and eyes which required numerous operations and a long recovery period. The young man was left with significantly impaired vision in one eye, deafness in his left ear and a total numbness on the left side of his face. Having been examined by Sir Stewart Duke-Elder, the nation's foremost eye specialist, he was told he had '...not a cat in hell's chance' of seeing active service given the severity of his injuries.

As a result, still undergoing recovery and attempting to pass the Medical Board, Sandys-Clarke was forced to wave his comrades off when the 5th Battalion was shipped out to the Far East in late 1941. Redesignated the 18th Battalion, Recce Corps, they made Singapore on 5 February 1942 and were taken Prisoners of War at the Fall of Singapore two weeks later. They lost 55 killed in the Battle of Singapore, whilst a further 264 died as prisoners at the hands of the Japanese.

Second Innings - into action

Having twice failed at the hands of the Medical Board, he kept trying in the forlorn hope of getting the opportunity to serve on the front line. On the third and final attempt, entering the Board, his heart must have stopped when faced again by Duke-Elder. "Can you feel this?" "Yes, Sir." "Can you see that?" "Yes, Sir." The surgeon knew very well that the answers ought, truthfully, to have been "No, Sir." However, having looked hard at the young officer and perhaps sensing his determination and courage, Duke-Elder permitted his passing, recommending that he be rated A1 by the Board.

In the summer of 1940 he had met, through his sister, Alys, Irene Deakin, whose family lived at Dimple Hall, Egerton, near Bolton. They were married on 12 July 1941, by which time Irene was serving as a driver in the First Aid Nursing Yeomanry.

Returned to duty in early 1942, he joined the 1st Battalion, The Loyal Regiment which had been operating on Home Defence duties since its role in the rearguard fighting at Dunkirk. A year later, in March 1943, the Battalion embarked at Liverpool to join the 1st Army in North Africa, as a part of the 78th Battleaxe Division. A fellow officer in the Battalion was Lieutenant Edward Deakin, Peter's friend and now brother-in-law. Watching the English coast slip away, Sandys-Clarke knew that his wife was carrying their first child, due to be born in but a few weeks.

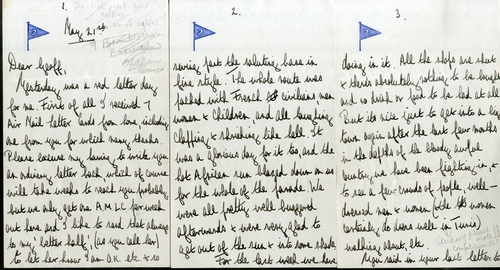

Having landed at Algiers by 9 March, they were taken along the coast by LCI to Bougie and thence Bone. Disembarked, they marched for Medjez-el-Bab and came up to their lines. Settling down to their duties, they were tasked with the removal of enemy mines, placing new counter-mines when possible and patrolling. The conditions were rather primal, as recalled in a letter to his father, dated 8 April 1943:

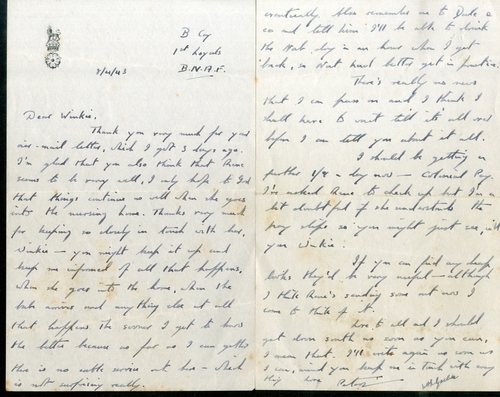

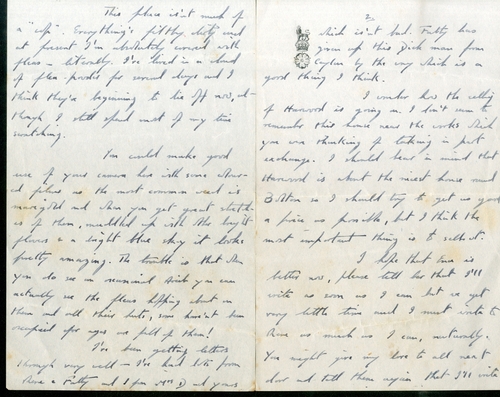

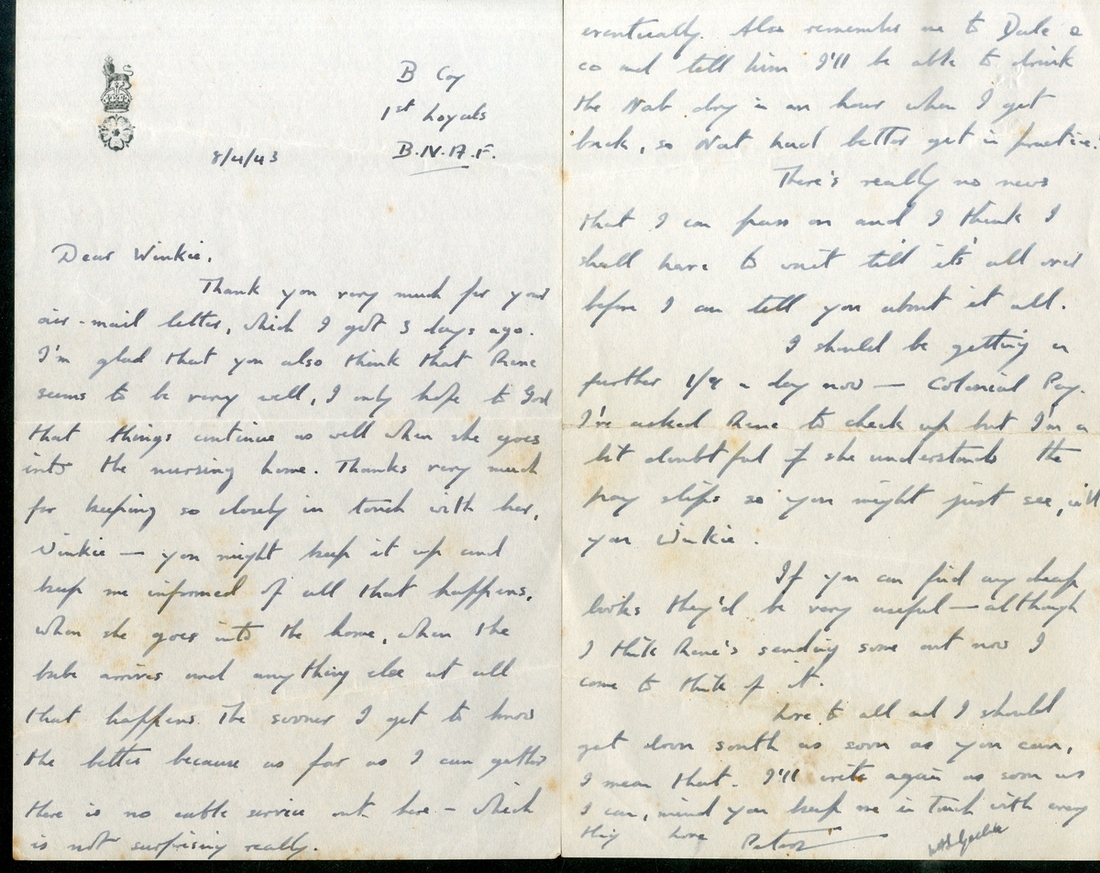

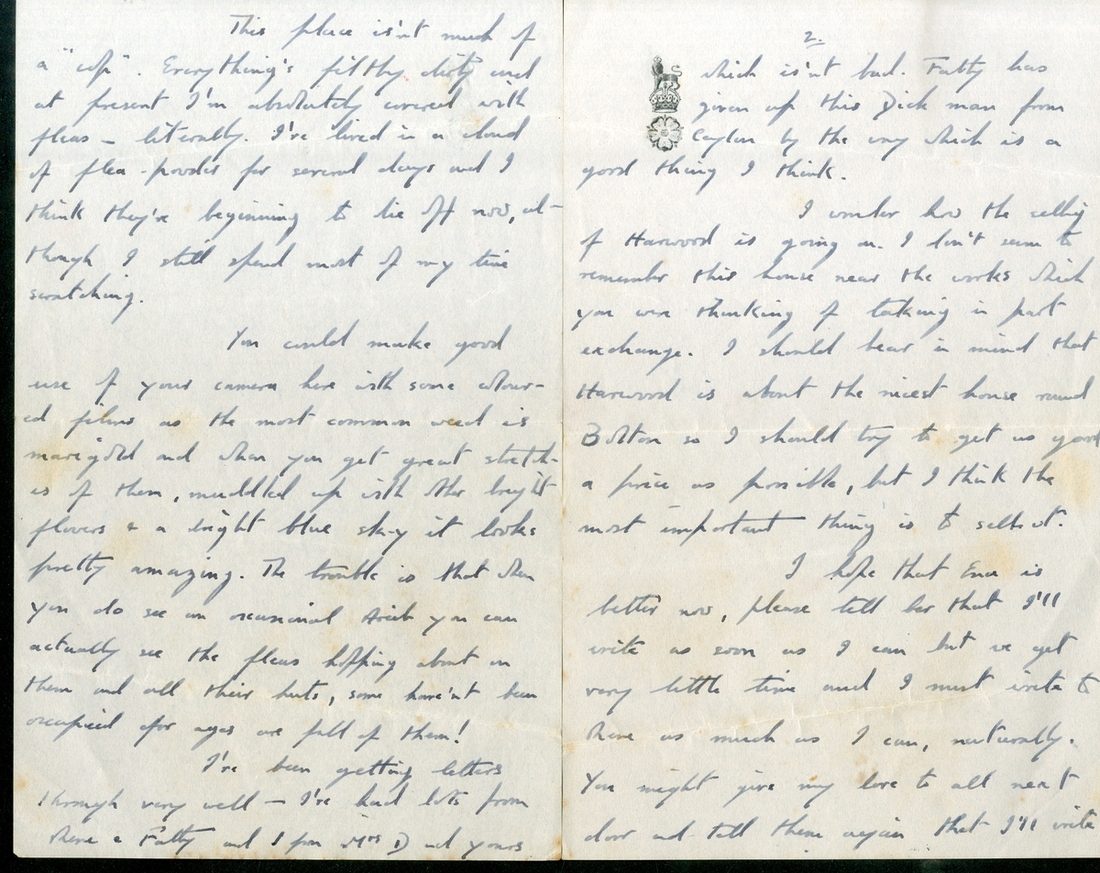

'Dear Winkie,

Thank you very much for your air-mail letter, which I got 3 days ago. I'm glad that you also think that Rene seems to be very well, I only hope to God that things continue as well when she goes into the nursing home. Thanks very much for keeping so closely in touch with her, Winkie - you might keep it up and keep me informed of all that happens, when she goes into the home, when the babe arrives and anything else at all that happens. The sooner I get to know the better because as far as I can gather there is no cable service out here - which is not surprising really.

This place isn't much of an 'up'. Everything's filthy dirty and at present I'm absolutely covered with fleas - literally. I've lived in a cloud of flea-powder for several days and I think they're beginning to die off now, although I still spend most of my time scratching.

You could make good use of your camera here with some coloured films as the most common weed is marigold and when you get great stretches of them, muddled up with the other bright flowers and a bright blue sky it looks pretty amazing…

There's really no news that I can pass on and I think I shall be here till it's all over before I can tell you all about it… I'll write again as soon as I can, mind you keep me in touch with everything. Love, Peter.'

A vast German attack was launched against their positions starting on 20 April from around 2200hrs. A battle of some twelve hours played out, with Allied tanks coming up through The Loyals; Sandys-Clarke and 'B' Company found themselves in the thick of events. They held their high ground in the west admirably - in what would be the first of several hot contacts with their Afrika Korps enemies in the coming days.

Gueriat-el-Atach - V.C.

On what was both St. George's Day and Good Friday, 23 April 1943, Sandys-Clarke and the 1st Battalion, The Loyals, with the 2nd Battalion, North Staffordshire Regiment on their right, were charged to take Gueriat-el-Atach. This was the formidable feature of high ground some five miles from Medjez-el-Bab. It was made up of no less than eight known Points for capture, together with a number of lesser positions. It stood as one of the strongest points in the line of German defences on the route to Tunis and was a key proponent of Operation Vulcan.

Commenced at 0200hrs, a creeping barrage and smoke shells helped cover the infantry - now making up the point of the spear - in their advance. By 0400hrs, 'B' Company were making good ground and had 16 prisoners for the bag at the cost of one killed and six wounded. The other companies had not made such light work of things: 'A' Company was pinned down in the face of a strongpoint and Forward Battalion HQ found themselves in a minefield, which cost the lives of the C.O., Lieutenant-Colonel Gibson and Major Coles, both mortally wounded.

As the British artillery fell quiet, the German artillery came to the party with great effect, together with an infantry counter. 'B' Company found itself faced by six armoured cars attempting to come up to their Point to drive them off. Command of 'B' Company devolved upon Sandys-Clarke when Captain Grant was killed. He answered the call of duty in the finest style, bringing up assistance with Churchill tanks. The determined band who remained on the hill (Point 174) inflicted as many casualties as they could on the enemy before themselves being driven off. They pulled back to the Forward Battalion HQ, or all that remained of it, where Sandys-Clarke found himself the only officer standing from those who had gone on to the hill that morning.

Sandys-Clarke was wounded himself, his glasses being shattered and blood pouring from his wounds, as recalled by his comrade, Colin Rushton, in a letter to the family many years later:

'…I can see it as if it was only yesterday when your father called for assistance because he had been wounded and blood was getting in his eyes, I helped him into a shallow gully where our three inch mortar was and I said we would get him back to the Medics. But he refused, he said just bandage it up. So I put my Field Dressing round his head roughly I may add, then he said he must go and help Captain Grant because he was alone and away he went. He was a brave man.'

Convinced of the fact that he could retake the objective and drive the enemy off Gueriat-el-Atach, Sandys-Clarke was granted permission to form a Composite Platoon. It was a truly selfless act from a soldier who had so many genuine reasons and opportunities to fall back in honour, from his damaged eye, which would have stopped most from even entering the field of battle, to the wounds which he had suffered, which must surely have further debilitated him. It was in this moment of resolution that Sandys-Clarke embodied the fact that those who earn a Victoria Cross are of a unique breed.

The acts which are stated in the citation are the stuff of legend and were observed by many comrades, including his brother-in-law who now wished him luck and watched as his intrepid group of soldiers began to make their way across the arid and battle-scarred Tunisian ground.

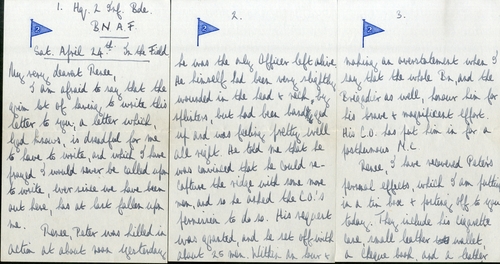

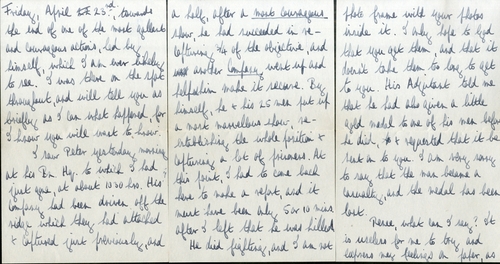

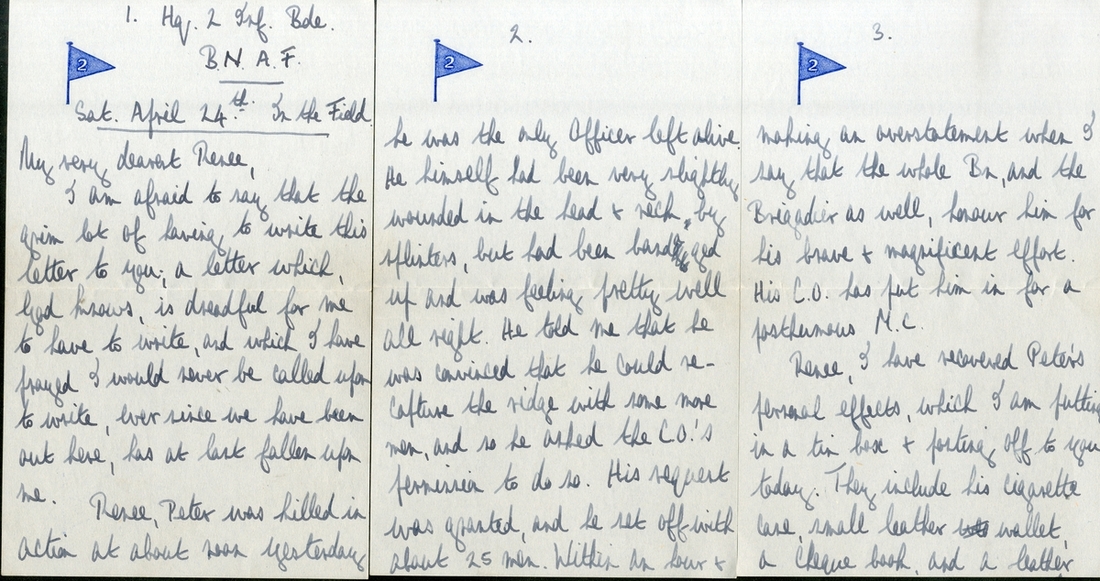

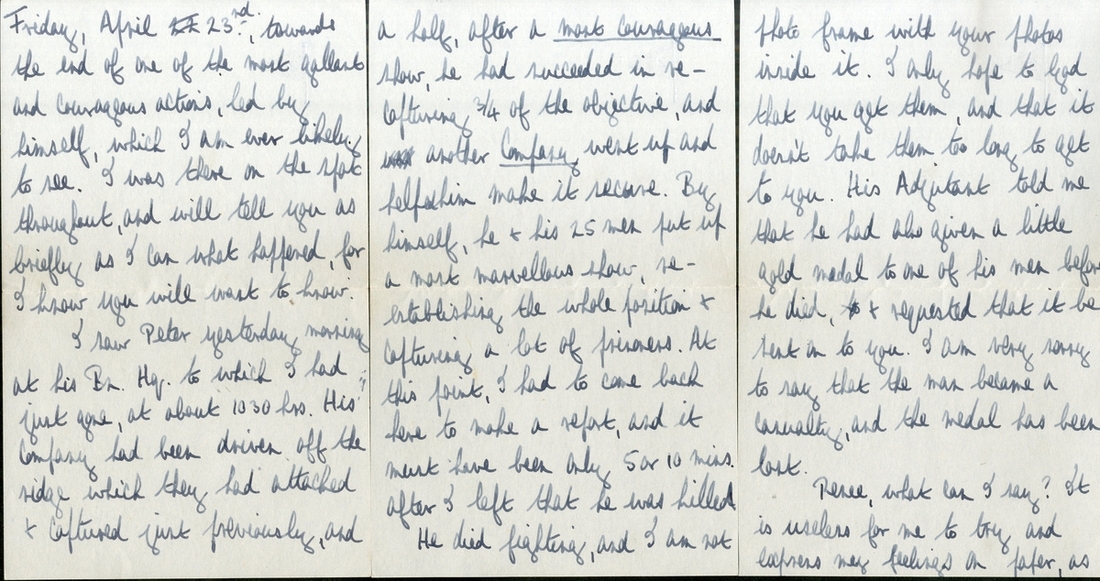

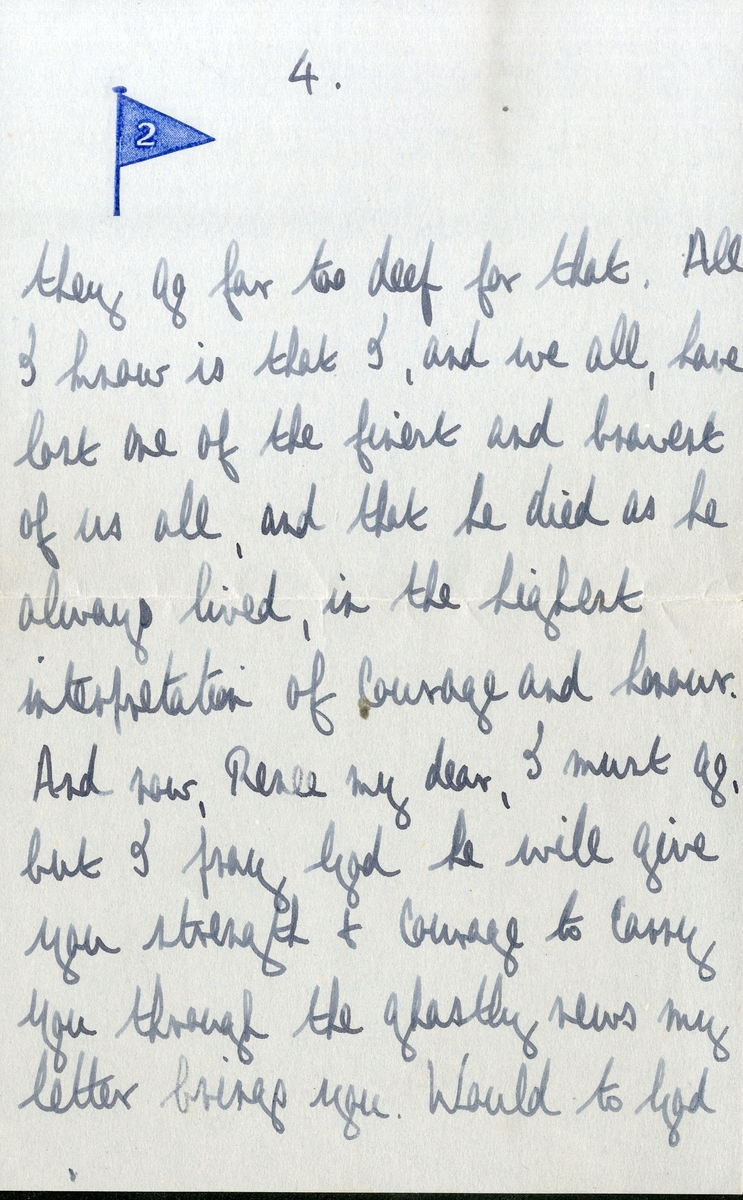

The following day, Easter Saturday, Edward Deakin sat down to write to his sister:

'24th April - In the Field

My very dearest Renee,

I am afraid to say that the grim lot of having to write this letter to you; a letter which, God knows, is dreadful for me to have to write, and which I have prayed I would never be called upon to write, ever since we have been out here, has at last fallen upon me.

Renee, Peter was killed in action at about noon yesterday, Friday, April 23rd, towards the end of one of the most gallant and courageous actions, led by himself, which I am ever likely to see. I was there on the spot throughout, and will tell you as briefly as I can what happened, for I know you will want to know.

I saw Peter yesterday morning at his Bn HQ, to which I had just gone, at about 1030hrs. His Company had been driven off the ridge which they had attacked & captured just previously, and he was the only Officer left alive. He himself had been very slightly wounded in the head & neck by splinters, but had been bandaged up and was feeling pretty well all right.

He told me that he was convinced that he could re-capture the ridge with some more men, and so he asked the CO's permission to do so. His request was granted and he set off with about 25 men. Within an hour & a half, after a most courageous show, he had succeeded in re-capturing ¾ of the objective, and another Company went up and helped him make it secure.

By himself, he & his 25 men put up a most marvellous show, re-establishing the whole position & capturing a lot of prisoners. At this point, I had to come back here to make a report, and it must have been only 5 or 10 minutes after I left that he was killed.

He died fighting, and I am not making an overstatement when I say that the whole Bn, and the Brigadier as well, honour him for his bravery & magnificent effort. His CO has just put him in for a posthumous VC.

Renee, I have recovered Peter's formal effects, which I am putting in a tin box & posting off to you today. They include his cigarette case, small leather wallet, a cheque book, and a leather photo frame with your photos inside it. I only hope to God that you get them, and that it doesn't take them too long to get to you. His Adjutant told me he had given a little gold medal to one of his men before he died, I requested that it was sent to you. I am very sorry to say that the man became a casualty, and the medal has been lost.

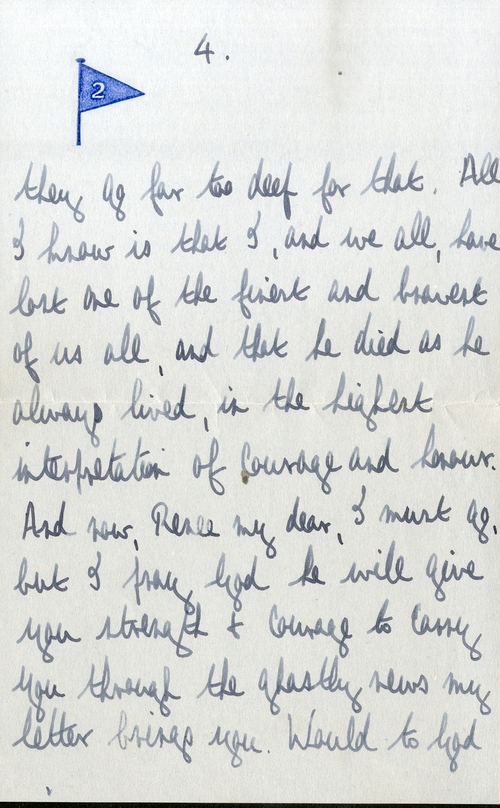

Renee, what can I say? It is useless for me to try and express my feelings on paper, as they go far too deep for that. All I know is that I, and we all, have lost one of the finest and bravest of us all, and that he died as he always lived, in the highest interpretation of courage and honour.

And now, Renee my dear, I must go, but I pray God he will give you strength + courage to carry you through the ghastly news my letter brings you. Would to God I had never had to write it. If there is anything that I can do for him, I will do it, and if you want any information about anything write to me and I will always do my utmost for you.

Always your very devoted brother, Edward.'

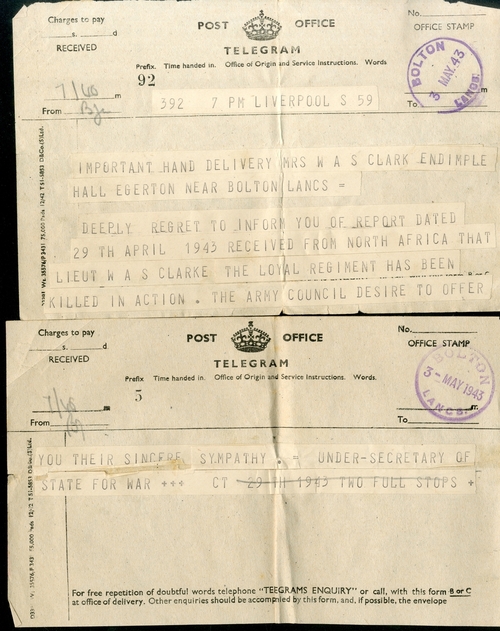

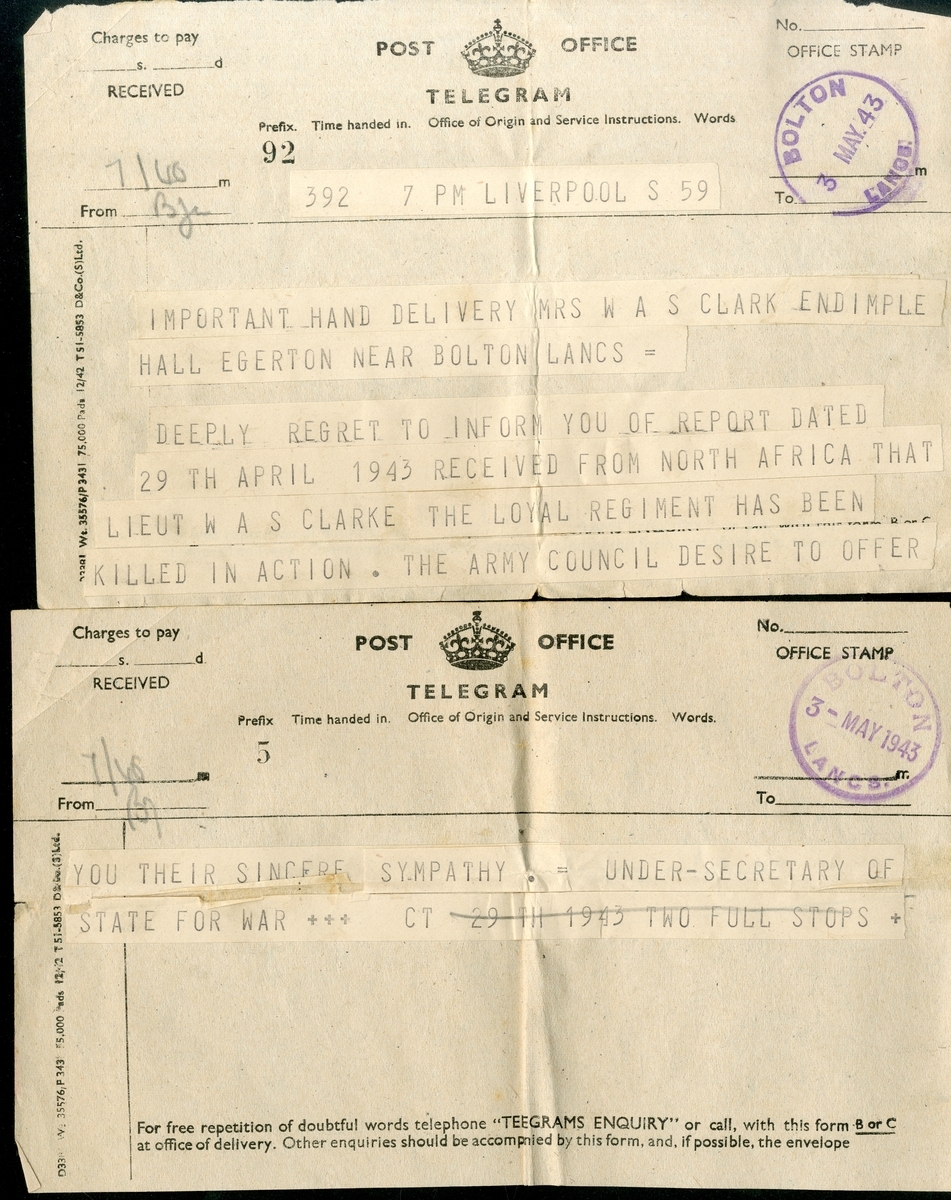

Irene's mother, Dorothy Deakin, would receive the official telegram of Sandys-Clarke's death dated 28 April 1943 and she would keep the secret of it from her daughter for a week until the baby had been born and mother and child were considered safe, visiting the nursing home daily and smiling through plans for a future she knew was about to be torn apart. Irene and Peter's son, Robin Peter, would be born on 1 May 1943, eight days after the death of his gallant father.

Sandys-Clarke was buried in the Massicault War Cemetery, his gravestone bearing the Regimental motto LOYAUTÉ M'OBLIGE (Loyalty Binds Me). He certainly lived up to that, and it is an interesting echo of one of his favourite quotes from Shakespeare:

"This above all: to thine own self be true,

And it must follow, as the night the day,

Thou canst not then be false to any man."

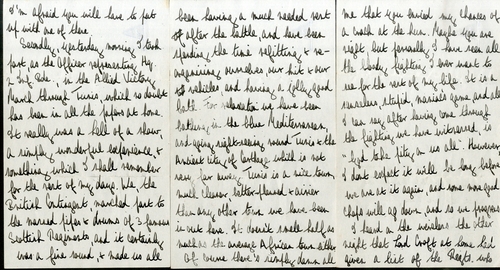

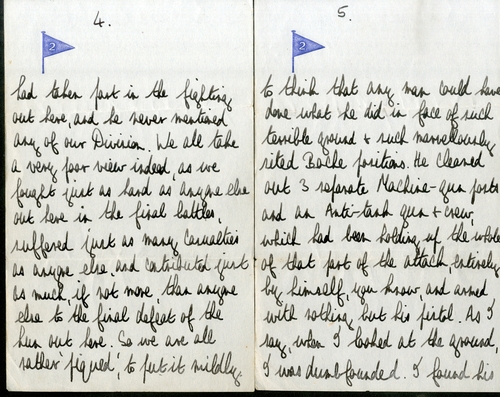

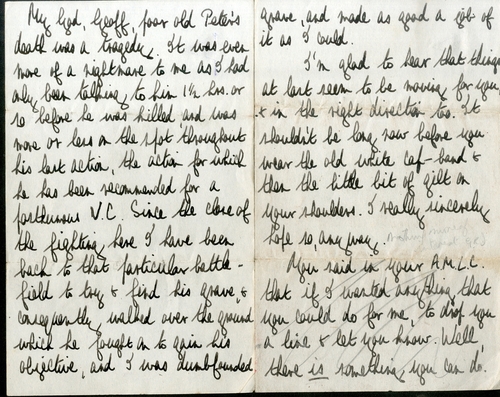

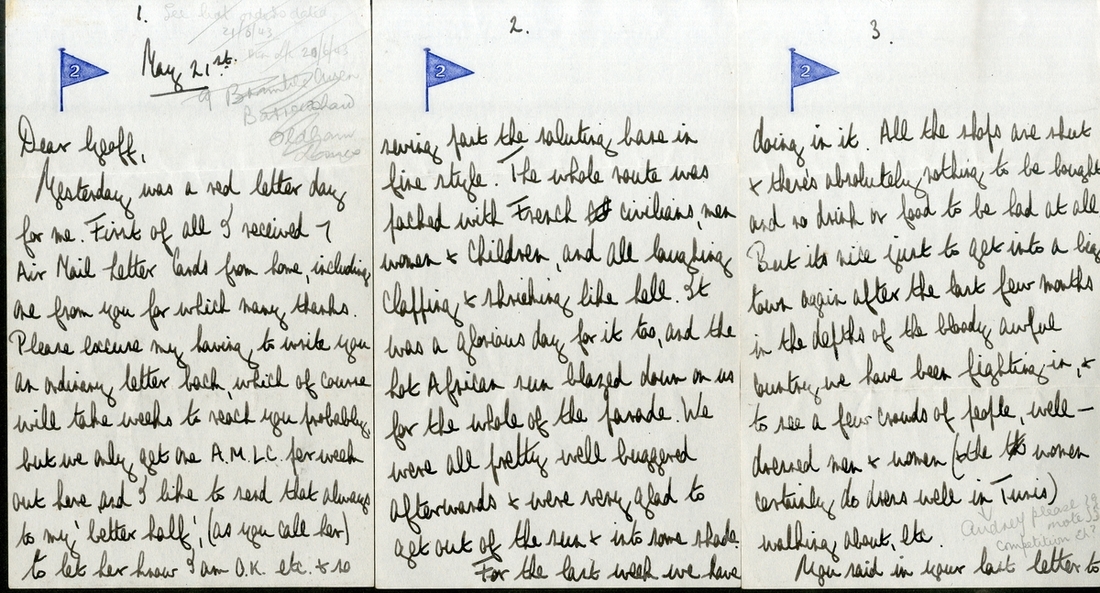

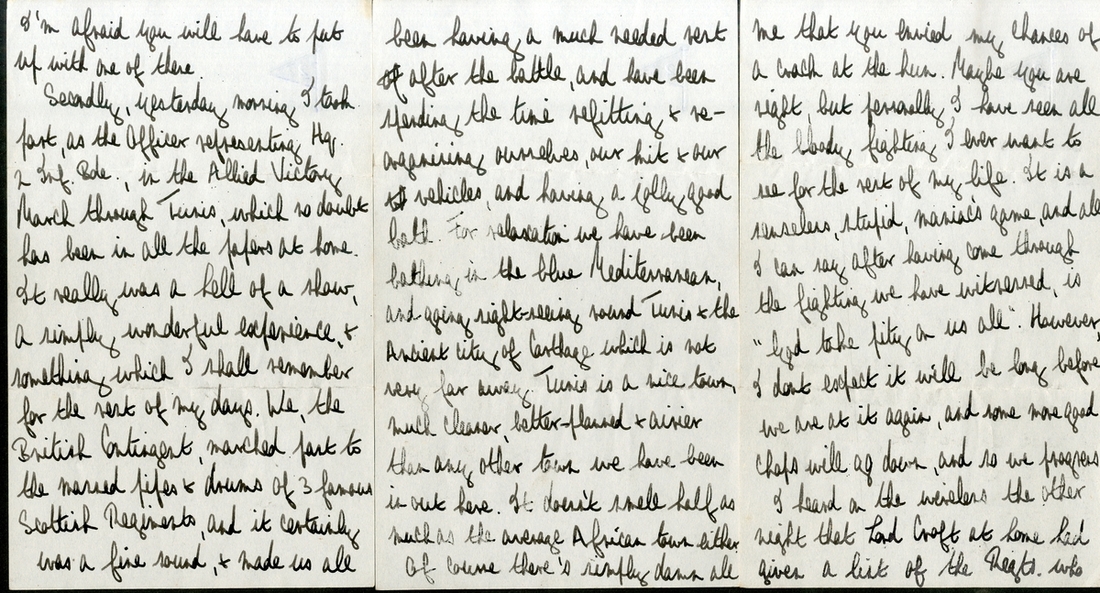

On 21 May, Edward wrote again, after the fall of Tunis, this time to his brother Geoffrey, a Subaltern in the Welch Regiment, destined for the 19th Indian Division in Burma, and gave more comment:

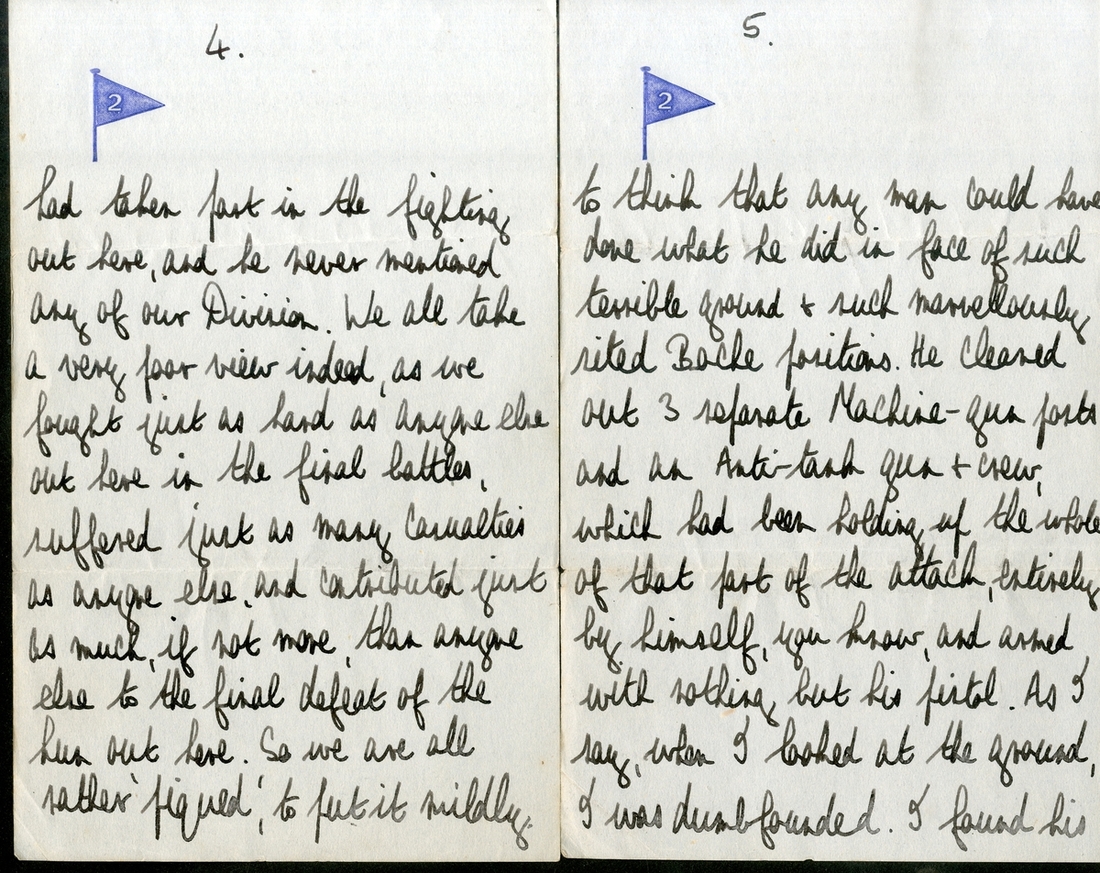

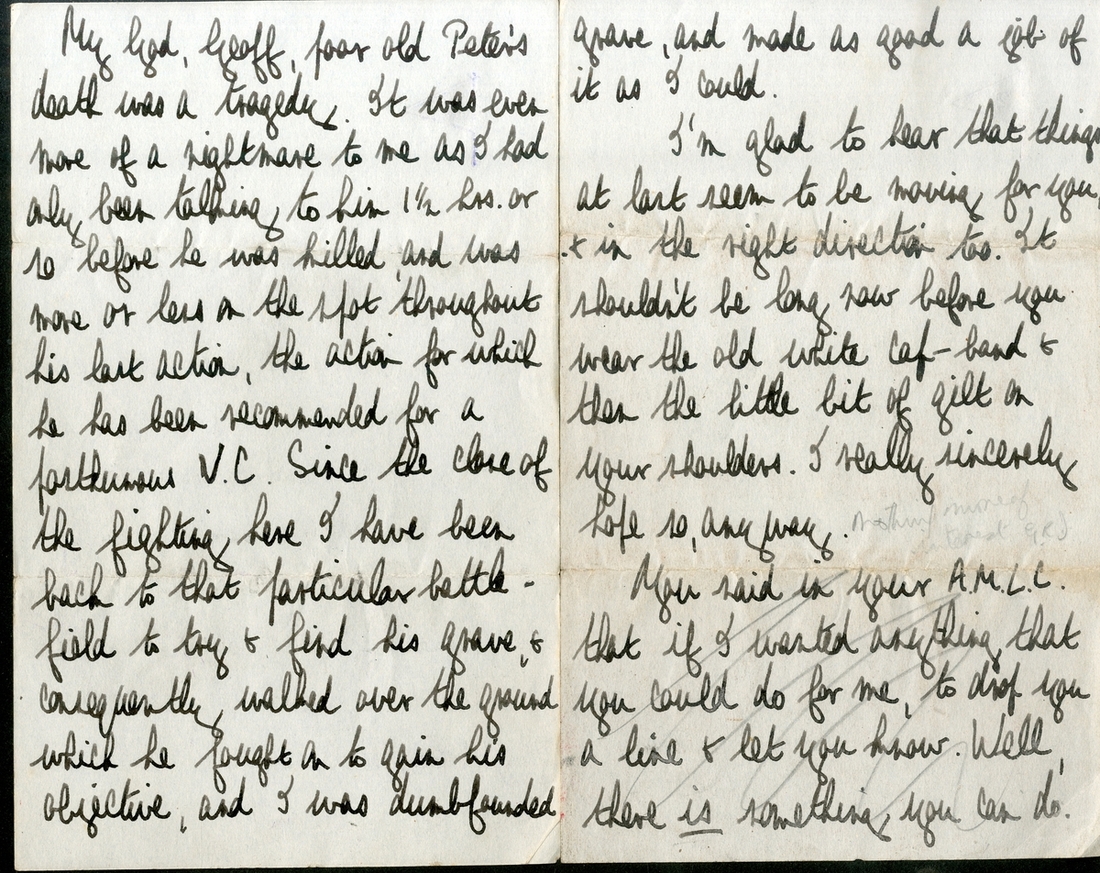

'…My God, Geoff, poor old Peter's death was a tragedy. It was even more of a nightmare to me as I had been talking to him 1.5hrs before he was killed and was more or less on the spot throughout his last action, the action for which he has been recommended for a posthumous V.C.. Since the close of fighting here I have been back to that particular battle-field to try and find his grave & consequently walked over the ground which he fought on to gain his objective, and I was dumbfounded to think that any man could have done what he did in the face of such terrible ground & such marvellously sited Boche positions.

He cleared out 3 separate Machine-Gun posts and an Anti-tank gun & crew, which had been holding up the whole of that part of the attack, entirely by himself, you know, and armed with nothing but his pistol. As I say, when I looked at the ground, I was dumbfounded. I found his grave, and made as good a job of it as I could.'

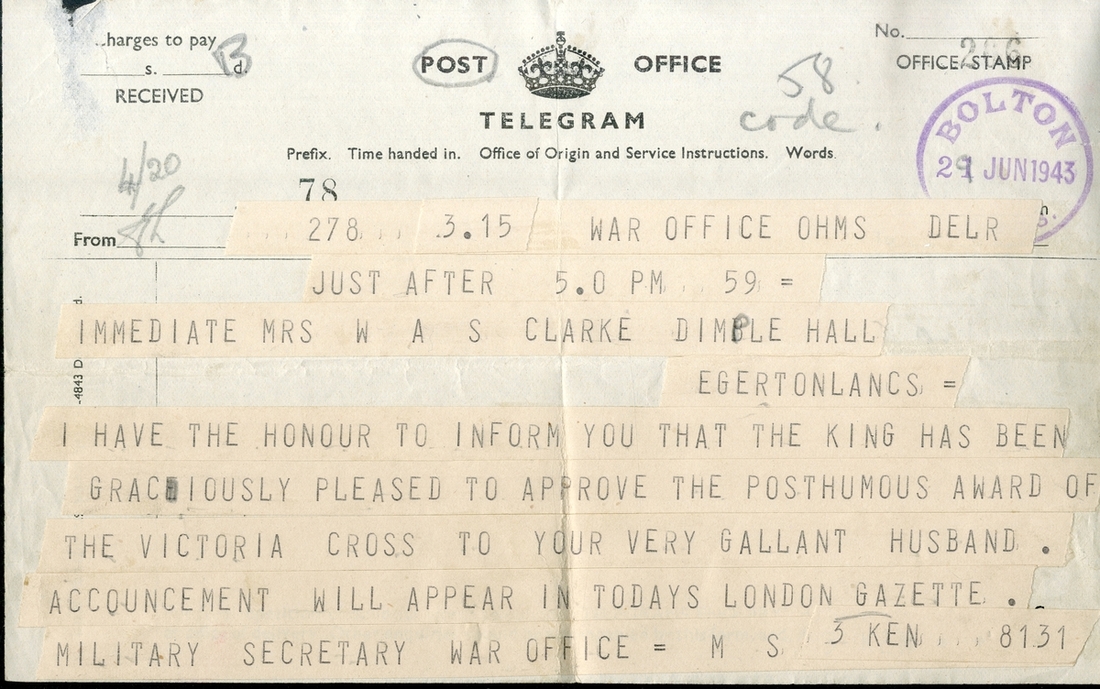

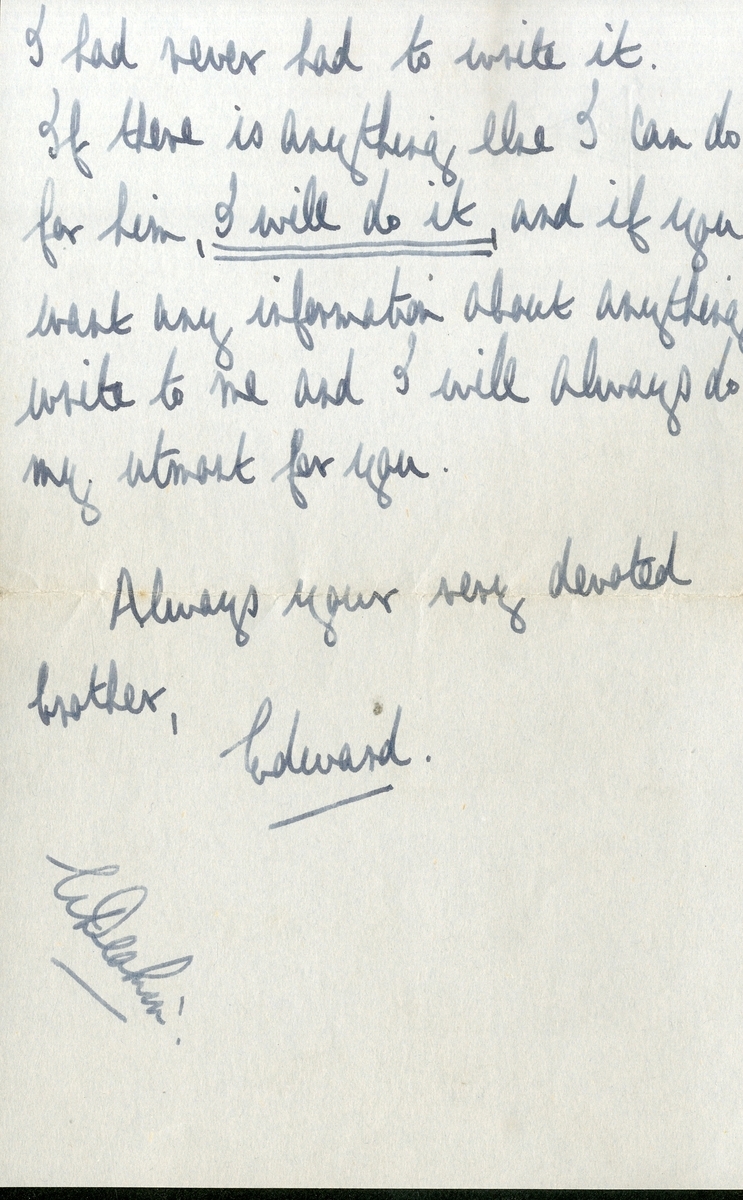

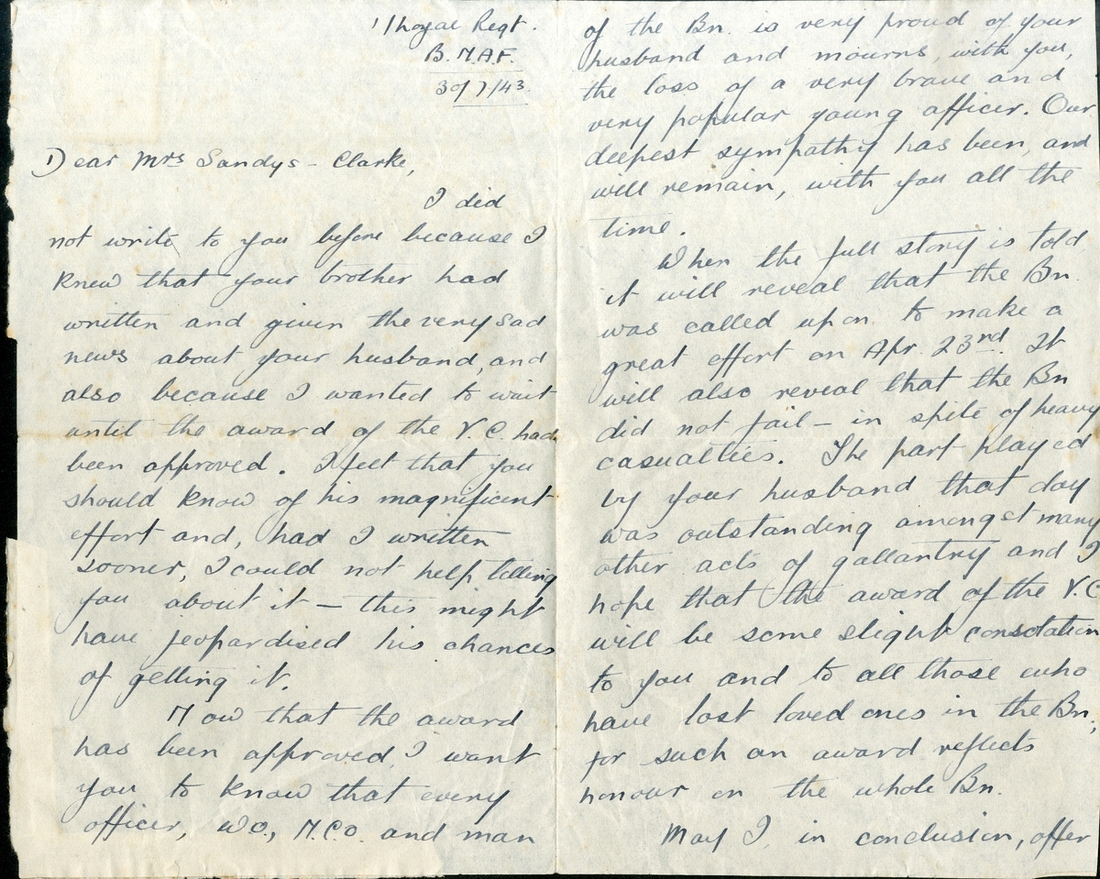

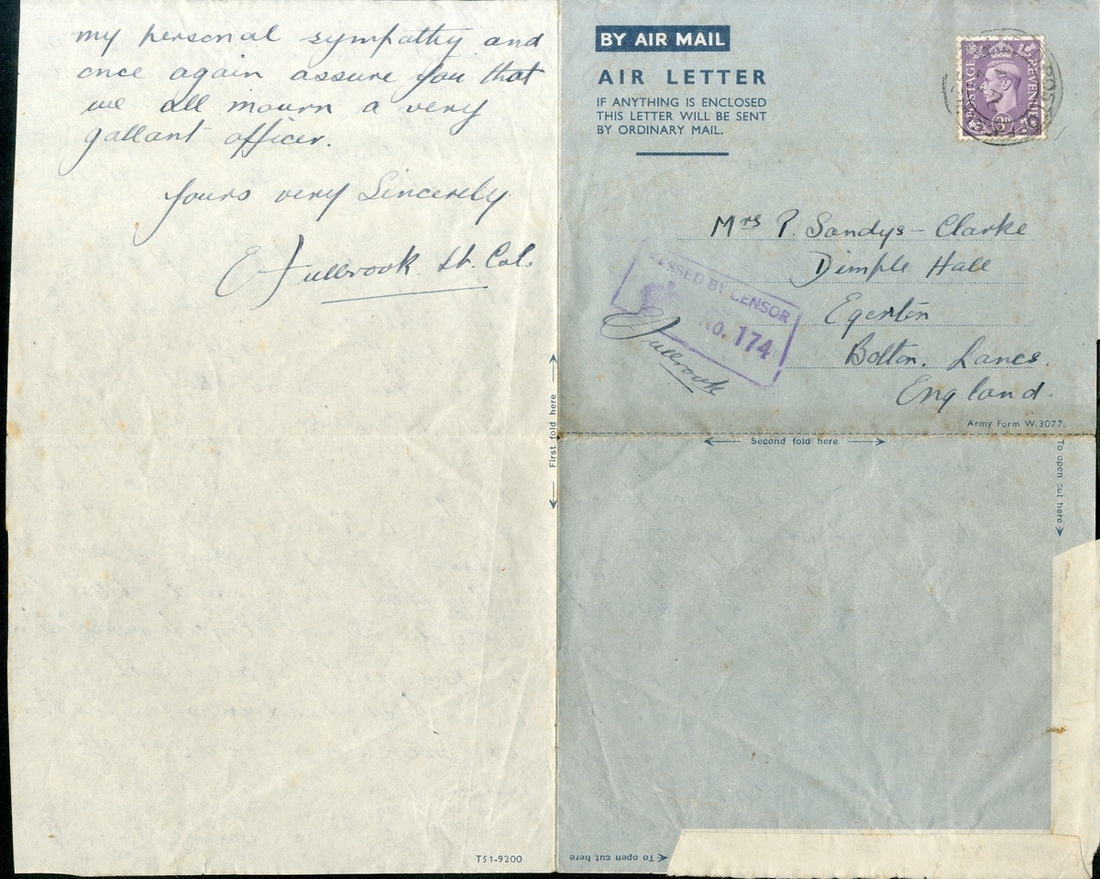

With final approval of the award of his Victoria Cross being published in June 1943, Mrs Sandys-Clarke, accompanied by her sister-in-law Alys, went to Buckingham Palace to receive the award from the hands of The King on 14 June 1944. On 26 June 1956, on the 99th Anniversary of the first award of the V.C. by Queen Victoria at Hyde Park, Lieutenant Sandys-Clarke's now 13yr old son, Robin, would go with his grandfather to share in the Victoria Cross march-past before Queen Elizabeth II. Some three hundred holders and their families, with over 20,000 spectators turned out for the historic event.

Sandys-Clarke is further commemorated upon the family gravestone at Bollington Church, Lymm, where a lectern in his honour was presented; in Preston, the home of The Loyals; at Uppingham School; in a painting at The Lancashire Infantry Museum; and at Southport where a paving-stone in the park commemorates the five V.C. holders born in the town.

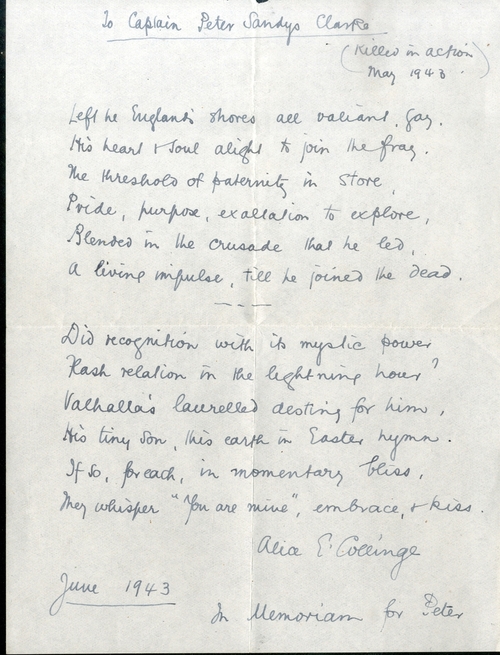

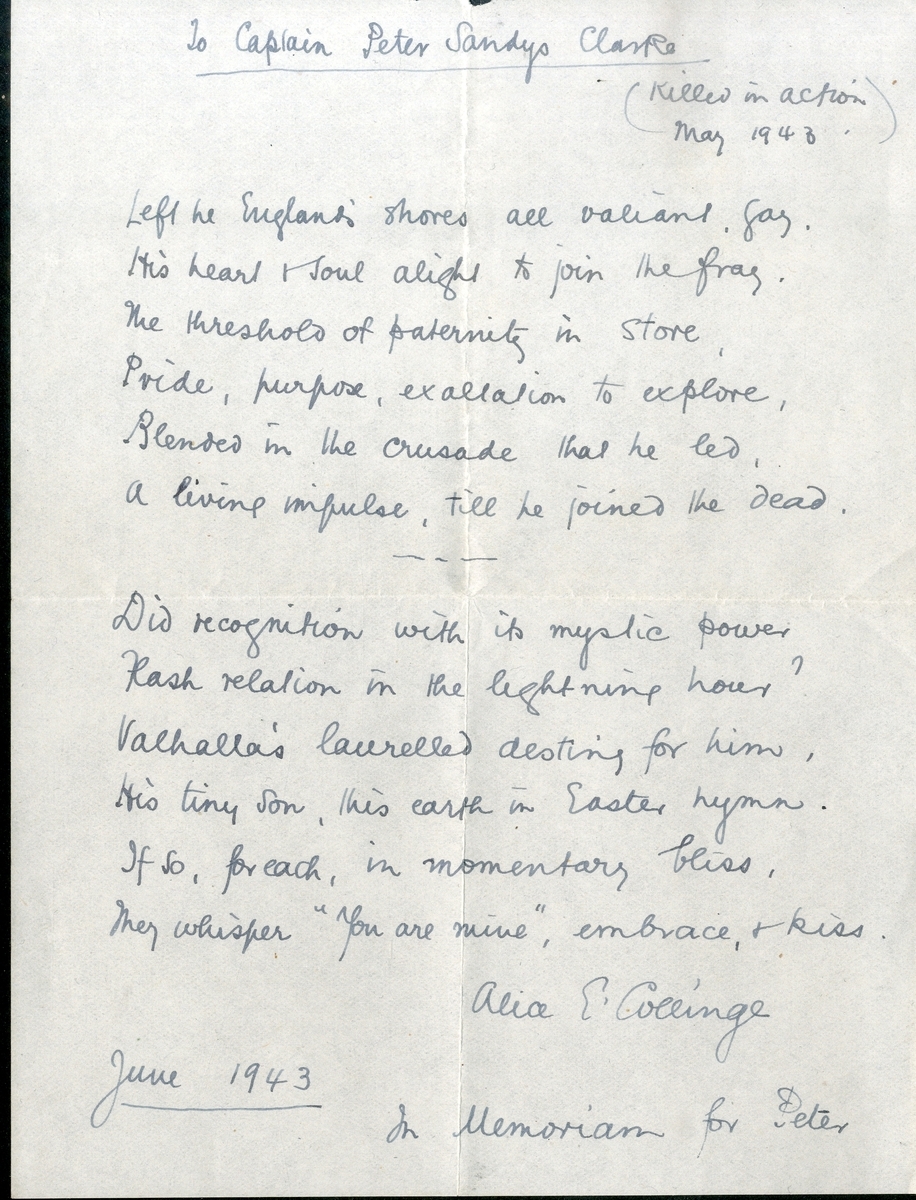

The following poem was sent to the family, penned by local poet and prominent suffragist Alice Collinge in June 1943, in his memory:

In Memoriam For Peter

Left he Englands' shores all valiant, gay,

His heart & soul alight to join the fray,

The threshold of paternity in store,

Pride, purpose, exaltation to explore,

Blended in the crusade that he led,

A living impulse, till he joined the dead.

Did recognition with its mystic power,

Rash relation in the lightning hour?

Valhalla's laurelled destiny for him,

His tiny son, this earth in Easter hymn,

If so, for each, in momentary bliss,

They whisper "You are mine", embrace, and kiss.

After the birth of their child, Robin Peter, Sandys-Clarke's widow, Irene, would write back to her brother Edward in May 1943:

"…No-one knows or understands better than I what it meant to Peter to get the chance, after his accident and everything it brought with it, to go out with you all to fight himself for all he held most dear in his heart. He used to be so anxious sometimes, that perhaps his chance might be denied him, and he always hated and shunned the thought of having to leave what he deemed as the great privilege to the other fellows. You may know those famous lines which were such favourites of his - " I could not love thee dear so well, loved I not honour more." Realising all this, Edward, as I do so clearly and utterly, how can I find it in my heart to wish that things had been otherwise? When I first heard, I knew that it would be something great that he did. And, of course, it was. His action has not surprised me. It was typical of Peter. Since I received your letter I have lived it all over, with him, and it is strange, my dear, but it seems to me I hear his voice in my heart, as I do so, and he is saying - "You would not wish it any different, Ree, would you?"… We have very often to pay very dearly for the things that count the most. The greater the value, the higher the cost. When I look back at all the incredible, perfect happiness I knew with Peter, Edward, once again I seem to hear him saying - "Is this too big a price to pay for all that we knew and shared together, Ree?" and again, there seems only one answer. " No, of course not." We have had what few people have had; what most people never never will have. We understood the true meaning of the word "Happiness"…. As Peter's wife I would be ashamed if I could not face the future. As Peter's wife I am proud to hold my head high…He is here with me now, as he always told me he would be, and in this sure knowledge I find my strength. He fought his battle upon earth, and he won."

Sandys-Clarke was a courageous warrior, no doubt; but also a young man on the edge of parenthood with his whole life ahead of him who made, as so many did, the supreme sacrifice for the free world, for King and country, for his fighting comrades and ultimately for the future of his family.

There is no typical Victoria Cross winner, and yet Lt. W.A. 'Peter' Sandys-Clarke embodied all the strengths and virtues which seem to set those men apart: selflessness, an instinct for action, and, above all, valour.

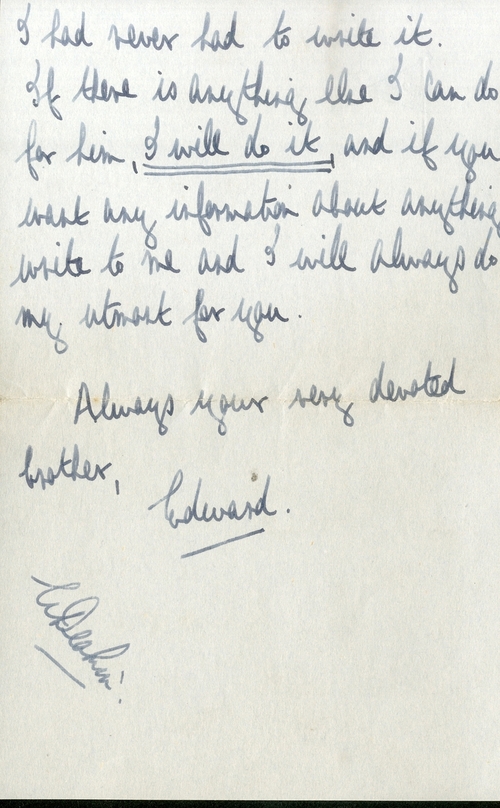

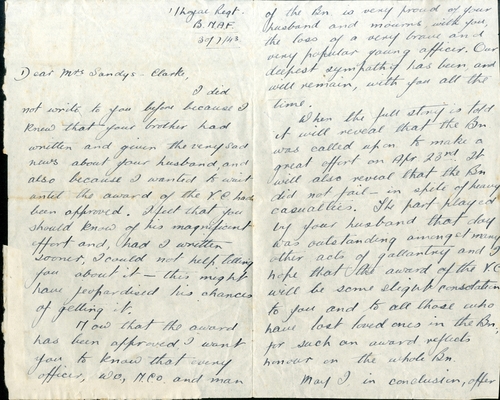

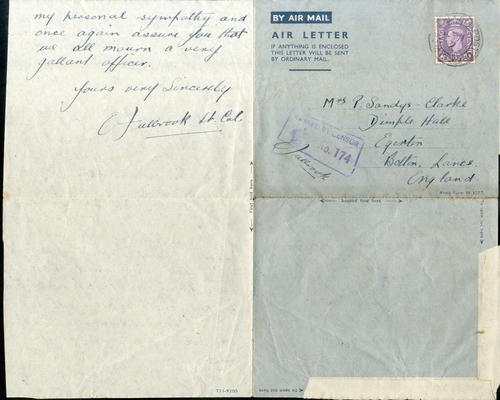

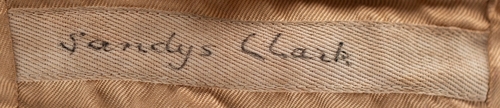

Sold together with a comprehensive original archive comprising:

i)

His Uppingham rugby cap by xxxx, the inner label with ink inscription xxxx, together with his OTC swagger stick.

ii)

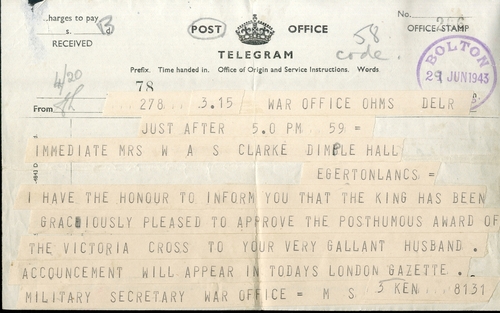

Telegrams to his wife, reporting the recipient as having been killed in action, dated 29 April 1943, and upon the award of his V.C., dated 29 June 1943.

iii)

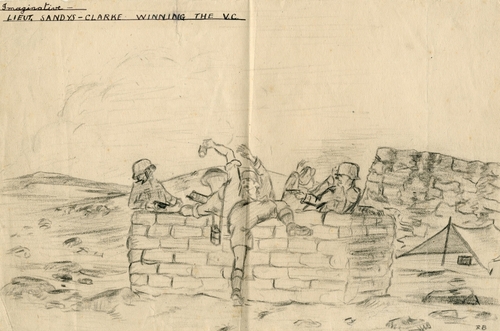

A finely leather bound album of newspaper cuttings and extracts relating to his life, death, award of the Victoria Cross, which also includes a sketch of his V.C. action, besides the account of his unit in Tunisia, by 'A War Correspondent'.

iv)

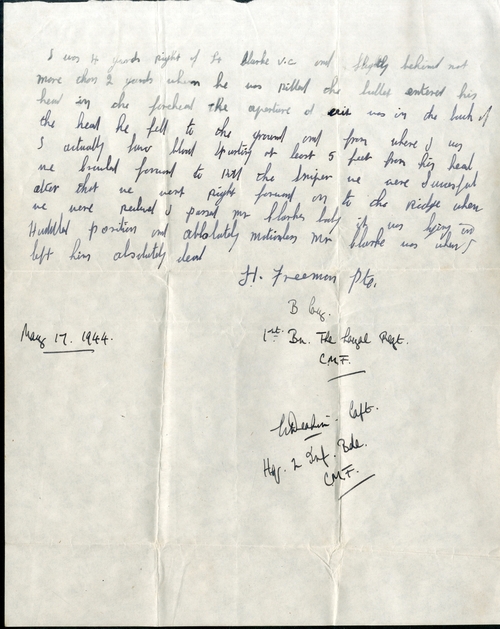

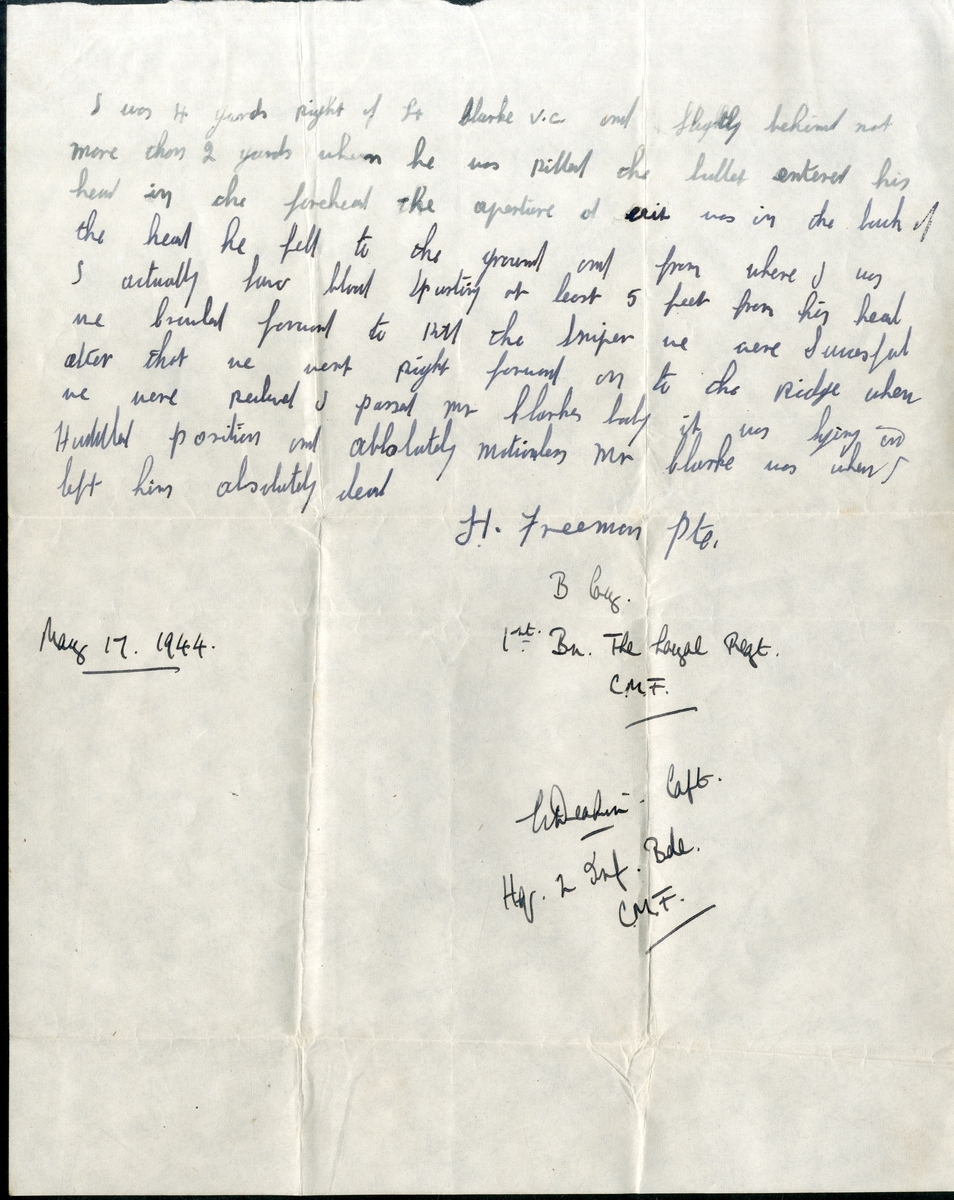

Various original photographs, including a statement, signed in May 1944 by Private H. Freeman, who gives his account of the final moments:

'I was 4 yards right of Lt Clarke VC and slightly behind not more than 2 yards when he was killed. The bullet entered his head in the forehead the aperture of exit was in the back of the head. He fell to the ground and from where I was I actually saw blood spurting at least 5 feet from his head. We crawled forward to kill the sniper we were successful after that we went right forward on to the ridge when we were relieved I passed Mr Clarke's body it was lying in a huddled position and absolutely motionless Mr Clarke was when I left him absolutely dead.'.

v)

Copies of several letters, poem quoted above and photographs.

Subject to 20% VAT on Buyer’s Premium. For more information please view Terms and Conditions for Buyers.

Sold for

£350,000

Starting price

£280000