Auction: 24005 - The Official Coinex Auction of Ancient, British and World Coins

Lot: 229

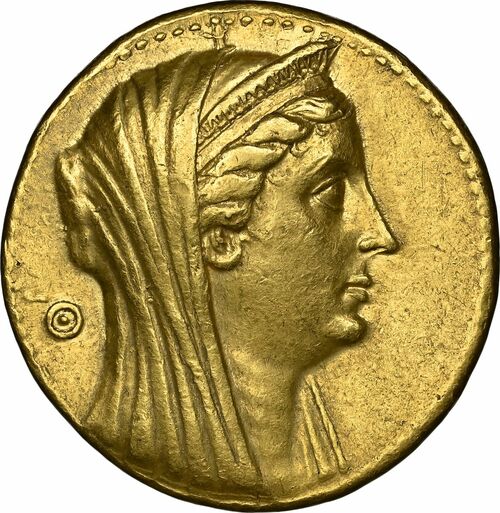

NGC Ch VF ~ Fine Style | Ptolemaic Kingdom of Egypt, Ptolemy II Philadelphos (282-246 BC), AV Mnaieion (Oktodrachm), struck in the name of Arsinoe II, c. 254-252, diademed and veiled head of Arsinoe right, theta before, rev. ARSINOIS PHILAEDELPHOY, double cornucopiae filled with fruits and bound with fillets, 27.76g (CPE 388; Svoronos 460, pl. 15, 12; Troxell p. 44, pl. 6, 2; Olivier & Lorber dies 1/30, 127-130; SNG Copenhagen 134), impressive portrait, perfectly centred, slightly softened to reverse but otherwise very fine to good very fine, in an NGC 'Ancients' holder, graded Choice Very Fine ~ Fine Style, brushed (Strike: 5/5, Surface: 3/5) [NGC Cert. #8221845-001]

Provenance

The "Estafefette No. 21" Collection of Ancient, English and World Coins

Spink 25, 24-25 November 1982, lot 141

A. J. Donald bt. Spink 1941

Minted by Ptolemy II as part of a vast commemorative coinage in tribute to his sister-wife Arsinoe II, this Oktodrachm (or Mnaieion), struck between 254 and 252 BC, is a wonderful example which perfectly showcases the depth of Ptolemaic portraiture. Contextually speaking, the Oktodrachm is bound up in the chaotic panoply of conflict with which the Hellenistic world was riven, and the frankly bizarre dynastic interweaving which characterised the successor Kingdoms of the Alexandrine Empire. Ptolemy II's first wife was Arsinoe I, daughter of King Lysimachos of Thrace and a distant cousin of his. As part of this marriage pact, made between Ptolemy I and Lysimachos against the Seleukid Empire, Arsinoe II was married off to Lysimachos, while another daughter, Lysandra, was married to Lysimachos' son, Agathokles. Ptolemy II had come to power following a vicious power-struggle with his half-brother Ptolemy Keraunos ('Thunderbolt') who likewise fled to the Thracian court in 287 BC, after which Ptolemy I named Ptolemy II his co-regent in 284.

Ptolemy Keraunos arrived at the Thracian court amid a personal power struggle between Lysandra and Arsinoe, as well as a wider dispute regarding foreign policy, relating to whether Lysimachos should press Keraunos's claim on the Egyptian throne, or continue supporting Ptolemy II. The chronology of this infighting is unclear, but the dispute culminated in the execution of Agathokles and the exile of Lysandra and, for the second time, Keraunos, this time to the court of Seleukid King Seleukos I Nikator, in 282. Seleukos, possibly encouraged by Ptolemy Keraunos and capitalising on this flurry of internal conflict in Thrace, invaded Lysimachos's lands in western Anatolia, culminating in the Battle of Corupedium in 281. Absolutely nothing is known for certain about this battle, other than that it ended in Seleukid victory and the death of Lysimachos. In the aftermath of his victory, Seleukos crossed the Hellespont into the Thracian heartlands. At this point, Ptolemy Keraunos had worked his way into Seleukos's inner circle, and murdered the Seleukid King, hoping he would be able to press his own claims on Thrace and Macedon. He established himself in the city of Lysimacheia, relinquished his claim to the Egyptian throne, and began the struggle for supremacy in the Aegean against the emergent King of Macedon, Antigonos Gonatas, whom he defeated at sea shortly thereafter.

Following Lysimachos' death, Arsinoe II had fled to the city of Ephesos. Popular riots erupted, supposedly due to the perception that Arsinoe had been responsible for the death of Agathokles and the subsequent collapse of Thracian control Keraunos had agreed to marry her and protect her young sons. However, Keraunos, who wished to push his own claim on the Kingdoms of Macedon and Thrace, had her two youngest sons killed. Her eldest son, Ptolemy Epigonos, has been argued by some historians to have re-emerged in the Illyrian Kingdom of Dardania, from which he launched a war to press his claim on the Macedonian throne, which occupied Ptolemy Keraunos for much of 280. Keraunos eventually met his end when he impetuously took on an approaching army of Celts in 279, without waiting for reinforcements. A deluge of Celts flooded into the Balkans and wreaked havoc for two years, until Antigonos Gonatas restored order and established himself has King of Macedon in 277. Arsinoe II, meanwhile, was forced to flee one last time, this time to Alexandria via Samothrace, and the court of Ptolemy II. It is unknown whether Arsinoe fled immediately after the death of her two younger sons, or after Antigonos took control of Macedon. Shortly after the arrival of Arsinoe II (although again, the chronology is patchy at best), Arsinoe I was accused of heading a conspiracy to oust Ptolemy from power and was exiled to the city of Koptos in Upper Egypt. Ptolemy then took the controversial decision of marrying his sister, Arsinoe II, in either 273 or 272 BC.

Such incestuous unions had been unknown in Egypt since before the days of the Persian conquest, but Ptolemy sought to imitate the Pharaohs of the old dynasties in resuming these 'sacred' marriages. Despite Ptolemy II's considerably effective and prosperous rule, which saw the construction of Alexandria's famous library and the lighthouse of Pharos, he was mercilessly criticised by the Greeks, who viewed the marriage as barbaric. They spurned Arsinoe with the nickname "Philadelphos" or "brother-lover" (a term charged with considerably more stigma in the third century BC than today), a title which both Ptolemy and Arsinoe adopted as part of their royal name. The double cornucopiae on the reverse of the Oktodrachm, a staple of later Hellenistic and Roman coins in the eastern mediterranean, pointed to the then immense wealth of Ptolemaic Egypt.

Subject to 20% VAT on Buyer’s Premium. For more information please view Terms and Conditions for Buyers.

Sold for

£9,500

Starting price

£4500