Auction: 24003 - Orders, Decorations and Medals

Lot: 209

Sold by Order of a Direct Descendant

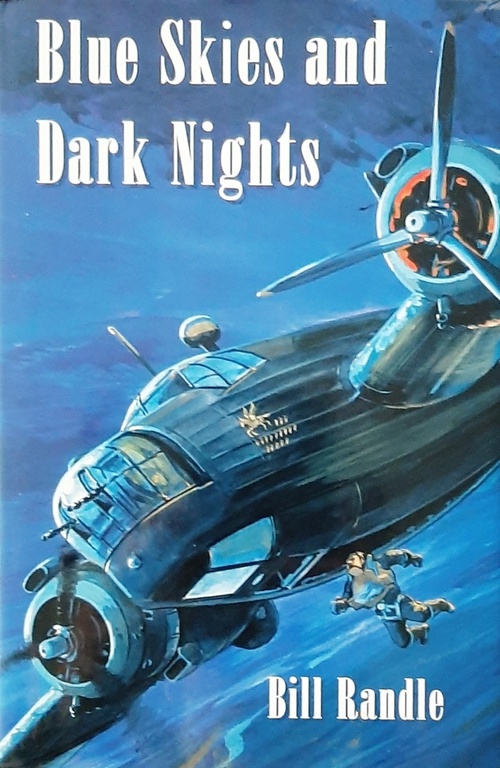

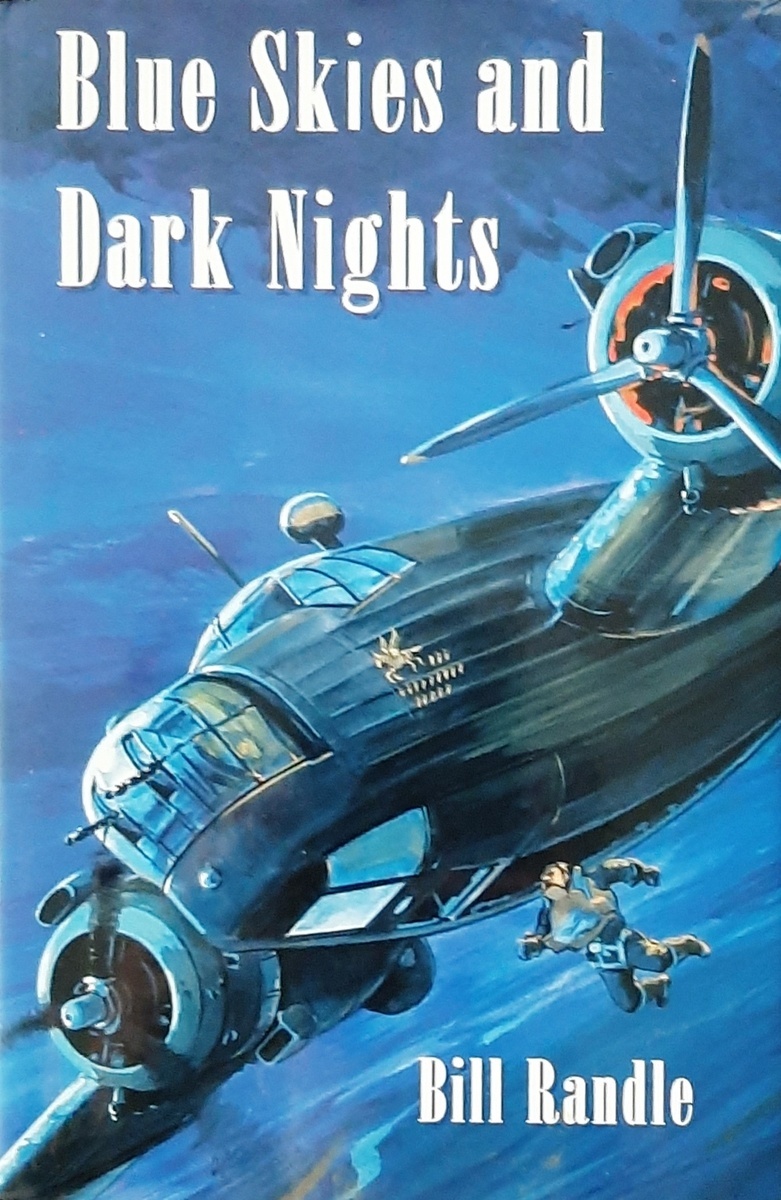

The outstanding 1967 C.B.E., Second World War A.F.C. and 'Evaders 1942' D.F.M. group of fifteen awarded to Group Captain, late Flight Sergeant (Pilot) W. S. O. Randle, Royal Air Force, who was further 'mentioned' and awarded the United States Air Medal after service in Washington and during the Korean War - his remarkable career is recorded in his well-known work Blue Skies and Dark Nights

Having been shot down after a raid on Essen on 17 September 1942, he made his way back to Britain via the famed Comete Line, flying back via Gibraltar just a month after his journey had begun, he was later to be Technical Consultant to the 1970's television programme Secret Army; he was made C.B.E. for his many years of charitable work, including raising millions for the Royal Air Force Escaping Society and being a key player in the establishment of the Royal Air Force Museum, Hendon

The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire, 2nd Type, Military Division, (C.B.E.) Commander's neck Badge, silver-gilt and enamel, with its case of issue; Air Force Cross, G.VI.R., reverse officially dated '1945' and additionally engraved '144393 W. S. O. Randle D.F.M. Bomber Command May'; Distinguished Flying Medal, G.VI.R. (1385872. F/Sgt. W. S. O. Randle. R.A.F.); 1939-1945 Star; Air Crew Europe Star, copy clasp France and Germany; Defence and War Medals 1939-45, with M.I.D. oak leaf; General Service 1918-62, 1 clasp, Malaya (Sqn. Ldr. W. S. O. Randle. R.A.F.); Korea 1950-53 (Sqn. Ldr. W. S. O. Randle. R.A.F.); U.N. Medal for Korea 1950-54; General Service 1962-2007, 1 clasp, Borneo (Gp. Capt. W. S. O. Randle. R.A.F.); Coronation 1953; Silver Jubilee 1977; Belgium, Croix de Guerre 1939-45; United States of America, Air Force Medal, mounted court-style as worn, light verdigris to sixth and seventh, very fine or better (15)

C.B.E. London Gazette 1 January 1967.

[O.B.E. London Gazette 31 December 1960.

[M.B.E.] London Gazette 1 January 1952.

A.F.C. London Gazette 7 September 1945. The original recommendation states:

'This officer has been engaged on instructional duties for 2 1/2 years. He has displayed outstanding keenness and enthusiasm and has been responsible for imbuing those working alongside him with a confident and cheerful spirit. He has always desired further operational work, but has never been allowed this to overshadow his work as an instructor. Never has he failed in his duties and he has maintained a high pressure in order to keep up the good quality of his pupils. This officer has served as deputy flight commander with success.

D.F.M. London Gazette 8 December 1942. The original Recommendation states:

'Flight Sergeant Randle has participated in 19 sorties. On 16th September, 1942, he captained an aircraft detailed to attack Essen. When nearing the target area, the aircraft was hit by anti-aircraft fire. One of the engines was put out of action but Flight Sergeant Randle flew on to his objective and bombed it. His aircraft sustained further damage by fire from the ground defences and could no longer be flown. The crew were forced to leave it by parachute. Flight Sergeant Randle descended safely and, evading capture, returned to this country in a remarkably short time. Throughout, this airman displayed high qualities of leadership, fortitude and determination.'

Recommendation from Wing Commander, Commanding 150 Squadron, dated 21 November 1942:

'Flight Sergeant Randle joined the Squadron on the 7th. July, 1942, since when he carried out 19 operational sorties, including sorties to Hamburg, Bremen and Essen.

He carried out all these attacks with persistent skill and courage and has shown superb captaincy and airmanship throughout his operational tour. His outstanding determination to press home his attacks, often in the face of heavy odds, has been a magnificent example to the rest of the Squadron. On the occasion of his last sortie on the 16th. September, 1942, he was detailed to attack Essen. When approximately 20 miles from the target, which he was approaching from the North, his aircraft was hit by anti-aircraft fire at 16,000 feet. The port engine was hit and failed completely but Flight Sergeant Randle, showing complete disregard for enemy opposition, and without considering his personal safety, continued on to bomb the target on one engine. Almost immediately after the bombs were released over the target, his aircraft received several more hits from enemy anti-aircraft fire and some time later the starboard engine also began to fail so Flight Sergeant Randle and crew were forced to abandon the aircraft. He has since managed to escape to this country in a remarkably short space of time. I consider that Flight Sergeant Randle's gallantry has justly earned him the award of the Distinguished Flying Medal.'

M.I.D. London Gazette 8 June 1944.

United States Air Medal London Gazette 10 August 1954.

William Samuel Oliver Randle was born on 17 May 1921 at Devon and was educated at Exmouth Grammar School and on completion of his studies joined Lloyds Bank working as a Bank Clerk living in Lympstone, Devon, prior to joining the Royal Air Force in 1941.

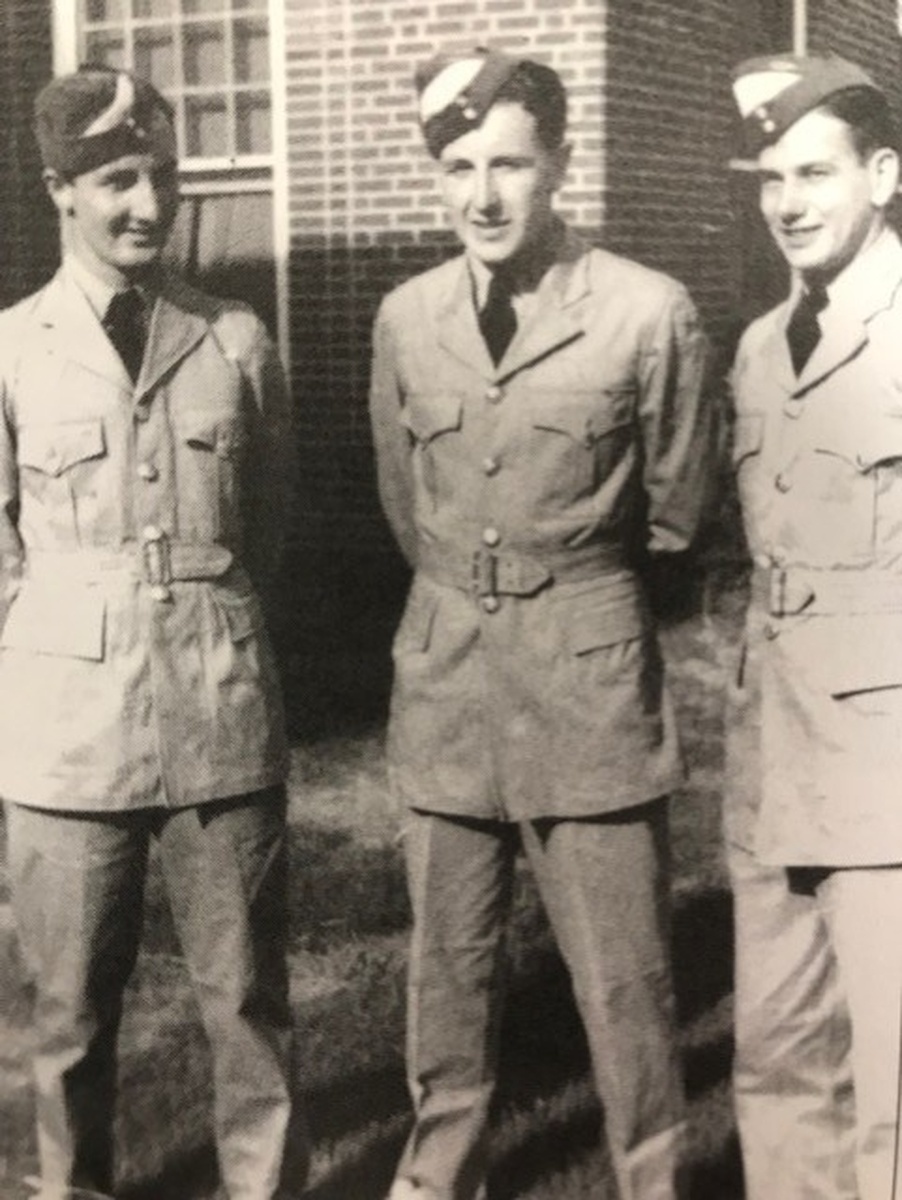

Training

Randle began his flying training in June 1941 at the No. 3 British Flying Training Schools at Tulsa, Oklahoma, U.S.A., in a Fairchild P.T.19. Moving to Miami, Florida in August he learned to fly the Vultee BT13A and finally the North American AT6 (Texan) on 29 September 1941. Returning to Britain in November of that year, he was stationed at No. 1 Advanced Flying Unit at Ternhill, Shropshire, flying Miles Master aeroplanes.

Moving to No. 1517 Beam Approach Training Flight based at Ipswich in January 1942, Randle flew Airspeed Oxfords the before moving swiftly on to No. 12 Operational Training Unit at Chipping Warden where he became to fly Wellingtons, his first Solo trip being on 4 April 1942. He suffered from a string of bad luck having a Forced landing on 16 June as a result of the engine seizing up due to oil starvation. Worse was to come on 21 June when the Wellington he was flying caught fire in Mid-Air and crashed at Dittington, the casualties were noted as follows in his Flying Log Book '...1 cow, 15 chickens, 1 barn, and 1/2 a house', with the crew sustaining cuts and bruises and frayed nerves. The aircraft was a write off.

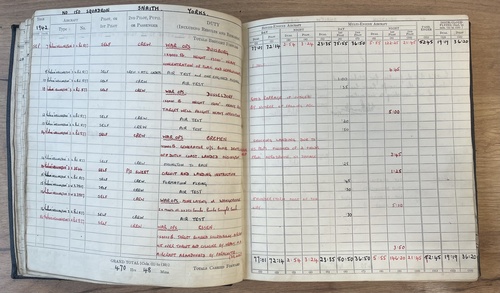

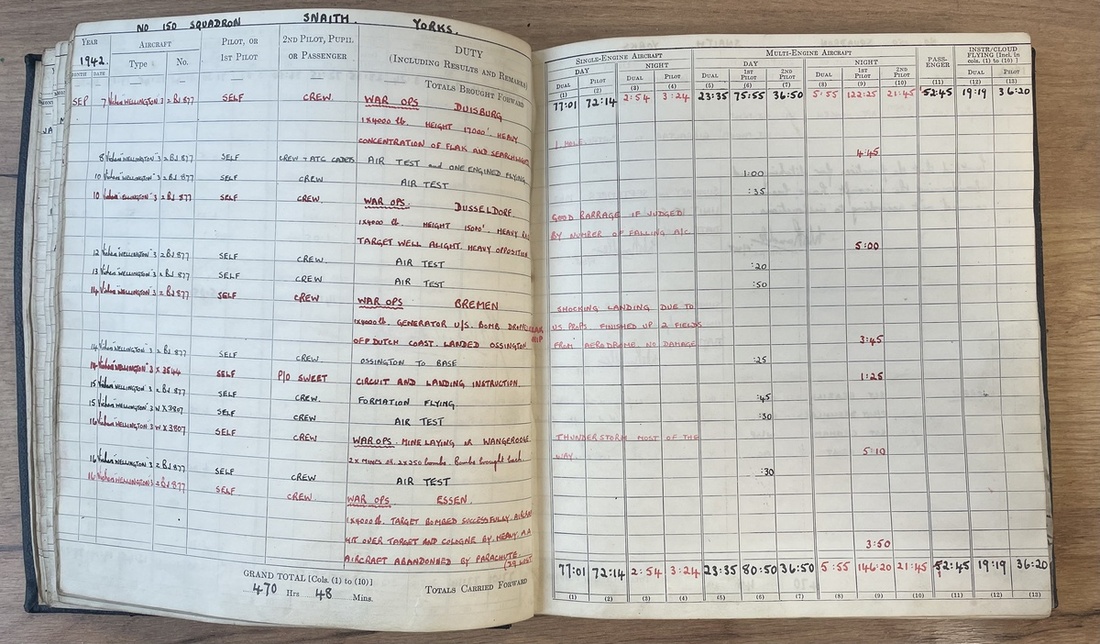

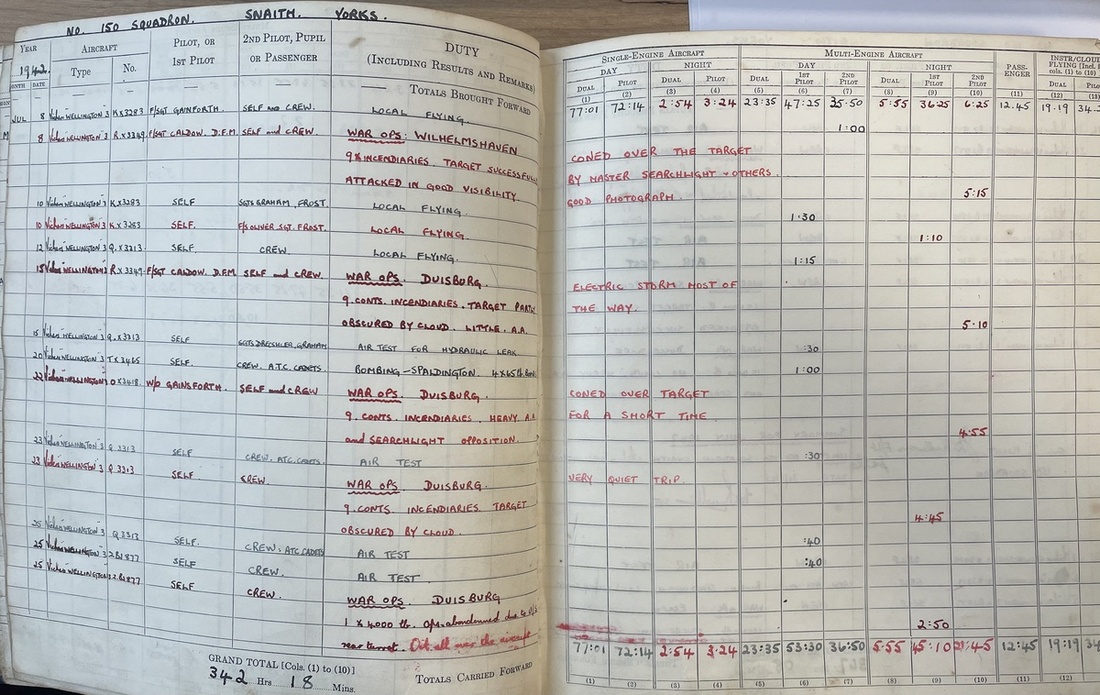

Operational Flying - 'The Best Raid to Date'

Despite this Randle moved to No. 150 Squadron based at Snaith, Yorkshire and flew his first Op on 8 July to Wilhelmshaven with 9 containers of incendiaries, during the raid he found himself coned over the target by searchlights. Two further Ops to Duisburg followed on 15 July and again on 22 July with both Ops each delivering 9 containers of incendiaries. Taking charge of his aircraft as Pilot on 23 July, again to Duisburg, he repeated the raid for a fourth time two days later on 25 July.

After a failed raid on Hamburg they flew a raid over Saarbrucken on 29 successfully dropping a 4,000lb bomb over their target, the crew repeating the feat over Dusseldorf two days later, again with a 4,000lb bomb. Randle's next Op was on 5 August with the target being Essen, however they suffered from severe icing and couldn't complete the journey, instead hitting the secondary target near Emden.

The following night he returned to Duisburg with incendiaries and then on 9 August hit Osnabruck, however during the attack the port engine suffered with Oil Starvation, his log book notes 'Returned to Base (Only Just)'. Targeting Maintz on 11 August with a 4,000lb bomb, the logbook notes 'This is about the best raid to date, target in flames'. This was repeated the following night with the comment 'Almost as Good as Above'.

His next Op was not until 24 August, over Frankfurt, followed by Kassel the next day and Saarbrucken the day after that. In the latter raid Randle found himself chased by a Me110 over the French Coast, noting 'Aircraft needs a wing change due to a fracture.'

Returning to Saarbrucken on 1 September 1942 this time with 6 containers of incendiaries and followed by a raid the next night over Karlsruhe. The pace of his flying increased steadily over the autumn with an impressive roster starting with an attack on Bremen on 4 September, Duisburg on 7 September, Dusseldorf on 10 September, Bremen on 14 September, each Op delivering a 4,000lb bomb. This may have taken a toll on Randle's aircraft, the last Op ended with his propellors failing resulting in an emergency landing two fields away from the Aerodrome.

Evader

In a change to his normal routine, the crew carried out Mine Laying at Wangerooge before undertaking what proved to be his final Op. They set out on 16 September for Essen, carrying a 4,000lb bomb, the target was bombed successfully but the aircraft was hit over the target and again over Cologne by heavy Anti-Aircraft fire with the crew being forced to rely upon their parachutes.

Randle's M.I.9 report takes up the story:

'M.I.9. Report: Interviewed 26 October 1942

Our aircraft took off from SNAITH, near DONCASTER, at 2028hrs on 16 Sept 42, and crashed on the return journey from ESSEN. The other members of the crew, whom we believe to be P/W, were:-

F/Sgt. DRESCHLER, W., front gunner; Sgt. BRAZILL, W., observer; and Sgt. GRAHAM, N., wireless/air gunner.

After bailing out I came down in the middle of an orchard at LOXBERGEN, S.E. of DIEST, Belgium, about 0030 hrs on 17 Sep. The parachute got caught in a tree, but I landed safely on the ground. I could not get the parachute off the tree, so I unstrapped myself and left it hanging. I scouted the village, and found no one about. I walked to a farm and saw down in a barn, where I stayed till dawn. Going out then, I found a peasant on a bicycle and stopped him. When I had convinced him I was British, he took me to a shack and later brought me food and an old pair of trousers, shoes, coat and a cap, taking away my uniform. I learned that the villagers had destroyed my parachute.

That morning the peasant guided me to HAELEN, where I bought myself a railway ticket to MONS. About 0900 hrs I got a train to TIRLEMONT. There I found the next train to MONS did not leave for another six hours. It took me about a quarter of an hour to get out of the station, and I then walked out of TIRLEMONT towards HUY. I returned to TIRLEMONT and sat for two hours outside the local German Kommandatur. Afterwards I walked North for bit. About 1546 hrs I got a train from TIRLEMONT as far as NAMUR, where I found the next train for MONS did not leave till after dark. I decided to spend the night in or near NAMUR. I left the town, crossing the river, and walked about 4km. I saw two men digging, and asked them for a bed. They guessed I was British and took me in, gave me food, and allowed me to sleep in a barn. After about two hours I was wakened by a man who asked me a number of questions, apparently designed to establish my identity. Another man came later and questioned me, and then a third man. The latter, who asked me if I wanted help to get back to BRITAIN, returned about 2200 hrs and we walked back to NAMUR, where he had arranged shelter for me. My host at NAMUR put me in touch with an organisation.'

A further extract from Blue Skies and Dark Nights takes up the story:

'I stayed in the safe house occupied by Madame Davreux and her two daughters for just four days. I did not realize at the time that I was already in the hands of the Comete Line, the most successful of all escape routes operating to return shot-down aircrew. The Davreux added the finishing touches so I was ready to travel. I was already well-dressed and was in pretty good physical condition; I just had to be equipped with papers to enable me to pass from safe house to safe house, and to be given some sort of identity. Madelaine, one of the daughters, took me into Namur to have my photograph taken. It surprised me just how easily the job was done. I was photographed in a chemist's shop by someone who obviously knew why it was being taken. Afterwards, we walked into the town where we sat in a cafe and ate croissants and drank coffee. Madelaine bought me a copy of the German magazine Der Spiegel which I thumbed through, glancing at the contents. It contained photographs of the slaughter of the Canadians on the Dieppe beaches. I was struggling to hide the distress which must have been showing on my face when I looked up to see a young Wehrmacht soldier, who was sitting at the next table, obviously approving my choice of magazine.

My 'laissez-passe' was ready the next day, complete with photograph and stamped to indicate that it had been issued in Antwerp. I was now a Flemish commercial traveller, Andre de Voulgelaar, born in Hasselt, but living in Diest. I was selling agricultural machinery and fertilizers. There was also a work permit which enabled me to travel in the Low Countries and in France. It even had a special visa for me to travel to Biarritz, of all places.

The Davreux family provided me with a small commercial diary and clothing coupons and instructed me how to respond to challenges in both French and German when asked for documents. I was reassured to learn that the Germans seldom spoke or understood French, they apparently just checked one's face against the photograph. The French police also took little notice of any papers, but to be on the safe side, it was best never to speak - just to hold out the document. My table manners were altered were altered in that, although knives and forks were used to eat, it was customary to leave them together, after the meal, diagonally across the plate, and not, north and south, as in England. They didn't like the way I walked, far too upright, they said, as though I was a soldier on the march. And I had to stop whistling and humming tunes, as most were American or British, and unknown on the Continent.

On my last day in Namur, I met a young girl who was to save my life. She was Andree de Jongh, only a little older than I, yet she was impressive with her firm purpose and ability. She spoke English quite well and briefed me to the letter on a journey to Brussels for which she would be my guide. I was full of questions, most of which she ignored. She emphasized the rules that applied when an evader was being guided and warned me that, if anything went wrong, I would be left on my own. I had to follow her to Namur railway station where I would present the ticket she gave me and then board the train to Brussels, making sure that I got into the same carriage, but to sit nowhere near her. On arrival in Brussels, there would be a change of guide, made in the entrance of the station. Another woman would take me to a large church where I was to sit in the third row of chairs on the right of the aisle. Then, I would be contacted by a man wearing a Belgian red, black and yellow boutonniere in his lapel. He would lead me to the next safe house.

She then answered the question that was uppermost in my mind. What should I do if anything went wrong? Where should I go? Her answer was abrupt, I should use my common sense and find my way back to Namur. My few belongings were packed into a fine leather attaché case and I was given a stylish Homburg hat to wear. I must have looked the part of an earnest commercial traveller. I paid my heartfelt thanks to the Davreux family, all of whom embraced me and wished me 'bon voyage'. I followed Andree as briefed, walking briskly about twenty yards or so behind her, down into Namur. At the railway station barrier, I presented my ticket to an uninterested collector and went in, carefully watching Andree as she boarded the train. I followed and took a seat at the end of a third-class compartment from where I could keep her in sight.

The journey to Brussels was uneventful. For the first time, I felt that I was keeping abreast of events, confident I knew what to do, and that I had a good chance of getting safely back to England. On demand I twice presented my ticket to an inspector. No one spoke to me or bothered me and just before mid-day we arrived at Brussels Midi.

I followed Andree through the crowds leaving the station. In the forecourt, she appeared to meet a friend. They walked for a while together and then parted company at a street corner. I switched my attention to the other guide, another young girl. Taking up a position some distance behind her, she led me on what seemed to be a conducted tour of the city. It was all a enjoyable revelation to me. We stayed for a while in the Place des Princes looking at the flower stalls and mingling with sightseers, many of them German soldiers. We then made off into the old part, stopping just for a moment to stare at the Manikin Pis which was being photographed by a couple of Luftwaffe aircrew. After a while, we came out into a market place, at the top of which stood an imposing church. I watched carefully as my guide went in. I then went to the foot of the steps at the main entrance where I could see from a notice board that the church was Notre Dame du Sablon. I paused for a while, then went in, taking the Holy Water from a sculptured basin set in the place I had been told it would be. I self-consciously crossed myself as I paid my respects. I then went around a heavy wooden screen and walked slowly up the aisle towards the altar, passing my guide who was sitting at prayer, head covered and bowed. I stopped at the base of the altar set under a magnificent window with a large cross hanging overhead; genuflected, and then withdrew to sit in the third row of chairs to the right of the aisle. As I did so, I noticed that the guide was already on her way out of the church.

I sat there waiting for a while and then began to pray, giving thanks for my salvation and for the remarkably successful events of the past few days. I knew that I did not deserve such blessings and hoped that my due deserts as an avenging bomber pilot would be set aside by the Almighty. I prayed earnestly for the safety of my crew.

Almost as an answer from above, a portly, well-dressed man came to sit near me. I noticed that he was wearing the Belgian boutonniere. We sat alongside each other in silence for a minute or so, and then he got up and left. I counted off a minute, and followed him outside into the broad daylight, waiting at the top of the entrance steps and watching him cross to the other side of the road. When he got there, he turned and waved his hand in my direction, then walked off slowly to cross a busy main road and enter an ornamental garden shrouded with trees. I followed him into the garden, around a large stone pond in which goldfish were swimming, and up a semi-circular flight of steps at the back of which, in ivy covered alcoves, stood statues of ancient notables. We left the garden and I followed him along a narrow street which took us past a busy military headquarters, teeming with German soldiers. After about a quarter of a mile or so, we came to the entrance of an apartment block. The lift was not working so we climbed slowly up a staircase to the fifth floor. There the guide knocked on a door which was opened to allow him to speak to someone inside. He beckoned me forward and I was ushered in to meet a lovely, smiling, middle-aged lady. The guide kissed her on both cheeks and left.

My third "safe house" was a well furnished apartment, the home of a lady who greeted me as a guest, and spoke excellent English. She reminded me that I was a fugitive about to be hidden in a busy house in the very heart of Brussels. The Boche were in and out of the building every day, visiting their friends, mostly women. 'One always has to be on the lookout for them', she said, 'and for the wretched collaborators who are worse'.

I was shown around the apartment in which my hostess lived alone. We went through the various rooms where I was cautioned not to go near the windows which were overlooked from taller buildings across the street. She explained that if the apartment was raided, I should make my escape through the bathroom window, out down the fire escape or across the roofs of adjacent houses. She showed me how to open the window and then pointed to a trapdoor in the ceiling, a devious smile appearing on her face. She picked up a long bamboo rod, reached up, and rapped three times on the trapdoor. The door was opened and I found myself looking up in amazement at the beaming face of my rear-gunner, Bob Frost. "Pleased to see you, Bill," he said, "you certainly took your time." He came down followed by a broad-faced man, blond-haired man, who looked very Germanic. then, unbelievably, down came Sergeant Dal Mounts, the American whom we had taken on his first flight over Germany.'

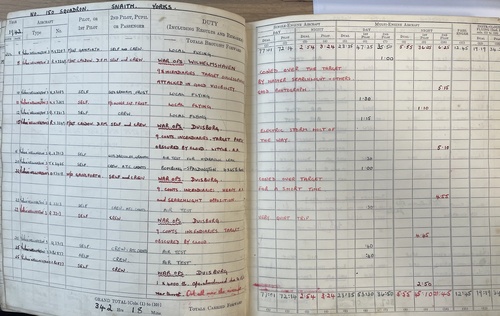

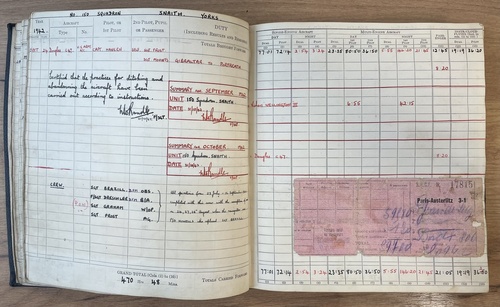

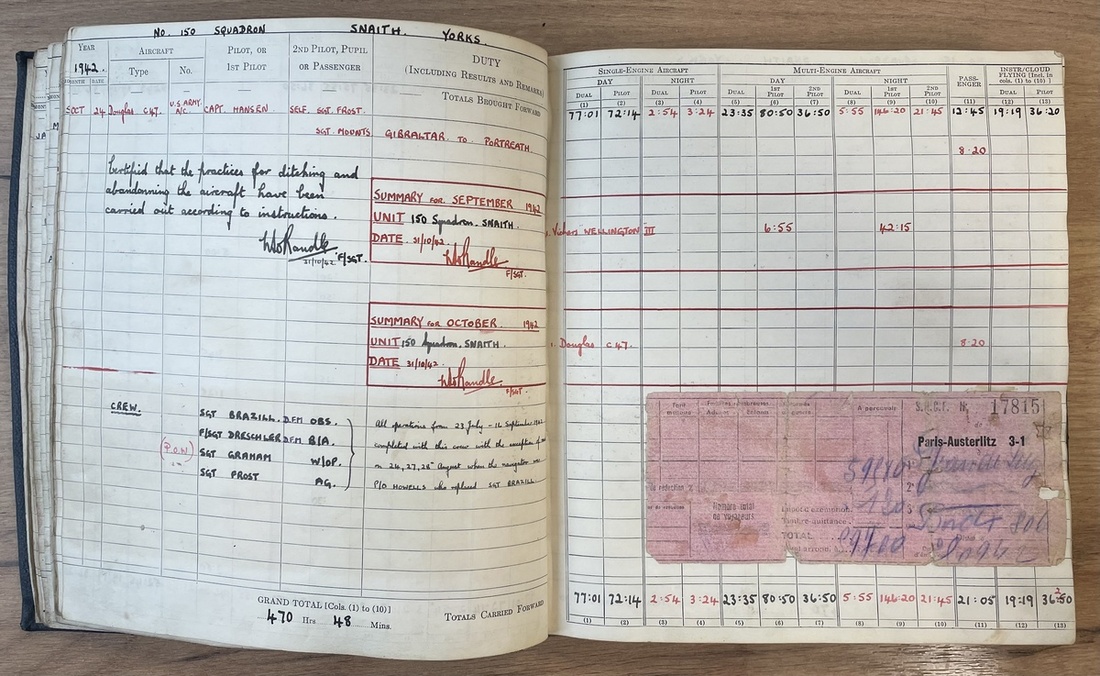

Randle's Flying Log Book recommences on 24 October 1942 with the flight from Gibraltar to Portreath, Cornwall in a C47.

Back in Blighty

Posted to Atherstone with 23 Operational Training Unit, based at Pershore, as an instructor flying Wellingtons. Randle transferred to 20 Operational Training Unit based at Lossiemouth in February 1944 having racked up over 1,000 hours of flying. He transferred again to 16 Operational Training Unit based at Upper Heyford in June 1945 with some flights on Oxfords. The unit moved to Barford St.John in July where Randle began flying on Mosquito IIIs.

Returning to operational flying, he transferred to No. 692 Squadron based at Gransden Lodge in September 1945, taking his first flight in a Lancaster on 26 September with a brief trip to Berlin (Gatow). Transferring again to 1552 (Radio Aids Training) Flight based at Melbourne, Yorkshire, this unit relocated to Membury and then on to Snaith in April 1946 and then to Full Sutton, Yorkshire.

Post War and The Far East

Randle was posted to Staff Duties at the Air Ministry in London on 26 July 1948 however, he kept his hand in with some flying at Hendon. Travelling to the United States in 1949 he explored the West Coast and even visited the Boeing factory at Seattle. Over the next year he travelled to the Far East, visiting Singapore, Malaya and Vietnam returning via Malta.

His time at the Air Ministry came to an end in December 1951 and he was sent as part of an exchange programme to the Headquarters of the United States Air Force in Washington later that month. Here he was to fly various types of aircraft, including the Mitchell and the Expeditor. Randle's first helicopter flight occurred in September 1952 in a Sikorsky H-19 helicopter, and this was followed by flights on a Bell H.13 on 25 October.

With the Korean War in full swing he left the United States and went via Honolulu and Wake Island at the end of November, landing at Tokyo International on 28 November. Posted to the 3rd Air Rescue Group stationed in Japan and Korea, his first Combat Mission was flown on 6 December aboard a Superfortress. This was a rescue sortie from Komaki to Nan-Do, Yo-Do and Orbit in Wonson Harbour carrying one inflatable lifeboat.

This was followed by a second mission later the same day with a rescue sortie from Komaki to Orbit in Wonson Harbour Area in support of front-line B.29 Bombers. He was to fly a further 11 Combat Missions from 13-21 December, carrying out Dumbo Orbit Ops in Albatross aircraft. His 14th Combat Mission took place on board a Dragonfly on 22 December, with a front-line evacuation and this was repeated the following day. Christmas Eve saw him carry out four further Combat Missions, the first dropping blood supplies to the front lines and later three front-line evacuations.

Having completed his tour Randle left for to the United States again on 13 January 1953 from Tokyo, returning to serve in Washington. He completed his service with them arriving home in April 1954 to be stationed at the R.A.F. Staff College at Andover, before being transferred to the Ministry of Defence in London in April 1955.

Randle began to fly jets from 1 July 1957 with a spell at 89 Refresher Flying Course at Feltwell in a Provost. He continued to learn between 1957-64 on a series of Refresher and Familiarisation courses during which he flew several kinds of jet including Vampires, Valettas, Meteors and Varsitys. Continuing to fly regularly, his third Flying Log Bok ends on 20 April 1960, with an impressive 3,040 flying hours listed. Deploying to Zambia on 1 December 1965, he returned to Britian on 28 February 1966, transferring to the Ministry of Defence. Appointed President of the Cranwell Board at the Officers and Aircrew Selection Centre at R.A.F. Biggin Hill, Randle finally retired from the Royal Air Force in April 1972.

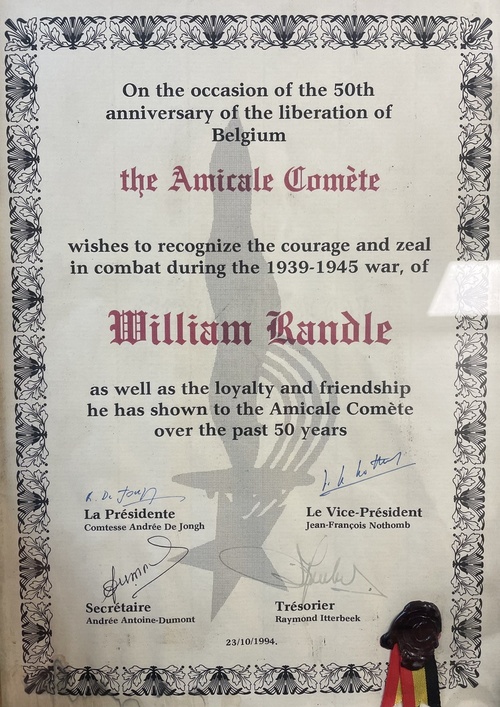

Epilogue - Escaping Society and Secret Army

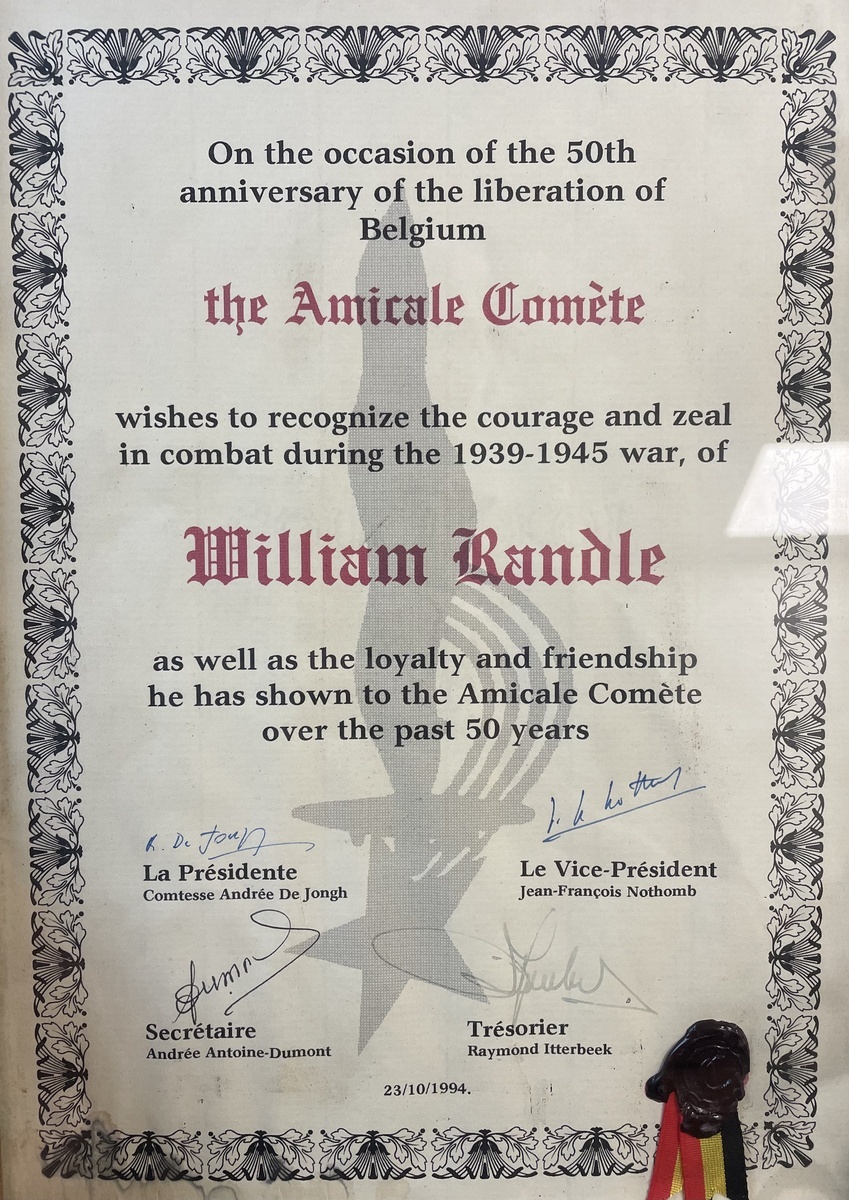

The Royal Air Force Escaping Society was founded in 1946 with Randle as a Founder Member, he used his contacts from his wartime escapades and as a committee member to arrange a visit to the base by some of the most famous figures of the Comete Line, including Andree de Jongh. He was appointed Chairman of the Society between 1974-77 and remained a member until it was disbanded on 17 September 1995 with the laying up of the standard at Lincoln Cathedral.

In addition to his work with the Escaping Society, Randle was involved with the early stages of the intended R.A.F. Museum to be based at Hendon, he began to take on fundraising roles and initiated flown covers which became a good fund raiser which over the years has raised millions of pounds for charity.

When he finally retired in 1972, he was approached to join the team engaged in the setting up of the Museum first as Public Relations Officer, then as Education Officer, Keeper of the Battle of Britain Museum, Curator of the Bomber Command Museum (at the opening of which he was reunited with his Wellington crew for the first time in 40 years) and finally as Director of Appeals, a post he left at the end of 1986. In addition he became Governor of the Royal Star and Garter Home between 1981-87 and a Fellow of the Royal Aeronautical Society.

Meeting the television producer Gerald Glaister in 1977 - a former photo reconnaissance pilot who made his name with the television programme Colditz - Randle attended a meeting at the BBC Television Headquarters at Wood Green. Following this, he became Technical Director of a series which was to be known as Secret Army the first four episodes of which were based on his experience.

The series ran for three years with Randle even appearing in the 36th episode dressed as a German infantry officer Oberleutnant Rath with two words to say, 'Mortars fire'. Firing his Luger he was 'shot' by an advancing company of Coldstream Guards who used their Sten guns to despatch him. Once Secret Army was completed he worked with Glaister again on a six-part series called 'Fourth Arm' a story about the training of agents in the Special Operations Executive.

Randle died at Tadworth, Surrey on 12 August 2012, with his obituary being published in the Daily Telegraph and The Times.

Sold together with a comprehensive original archive including:

i)

His four Flying Log Books.

ii)

Warrant for promotion to Pilot Officer, dated 13 March 1943 and Warrant for promotion to Flying Officer, dated 1 July 1946.

iii)

Certificates for the awards of the M.B.E., O.B.E. and C.B.E.

iv)

His original Comete Line pin Badge, together with Certificate for the 50th Anniversary of the Liberation of Belgium.

v)

Pingat Jasa Malaysia Medal, in box of issue.

vi)

A post-War United States Flying Suit, type 'Very Light', with Group Captain rank on the shoulders and an R.A.F. Odiham badge on the left shoulder.

vii)

Two R.A.F. sweetheart brooches.

viii)

An R.A.F. ring.

ix)

A For God and Empire brooch.

x)

A Belgium, Order of the Crown neck Badge.

xi)

A Nijmegen Cross with '50' on riband with miniature (without 50).

xii)

A large painting style photograph of him in No.1 uniform.

xiii)

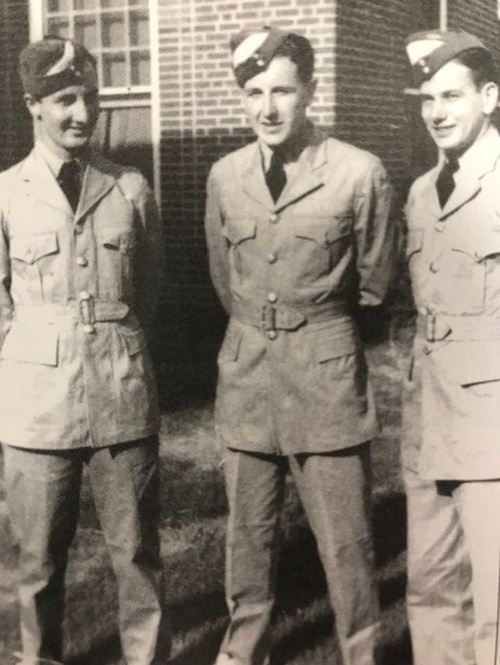

A black and white photograph taken at R.A.F. Odiham wearing full No.1 uniform.

xiv)

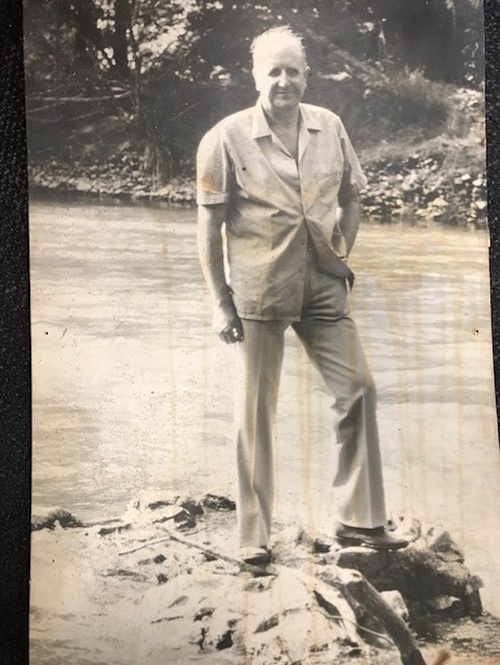

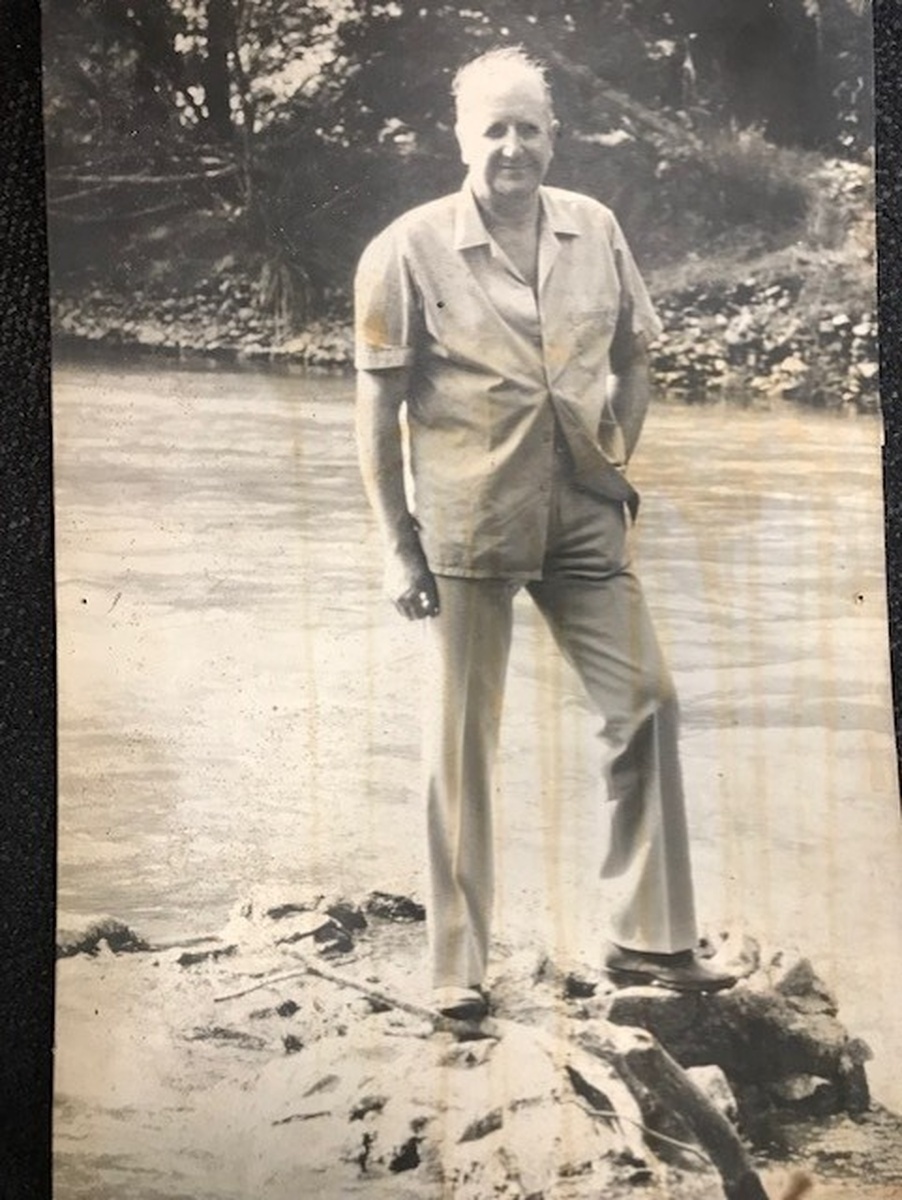

A large photograph of him in civilian clothing taken in the Pyrenees.

xv)

A copy of Blue Skies and Dark Nights (signed) with a further unsigned copy.

xvi)

A copy of Kondor.

Subject to 20% VAT on Buyer’s Premium. For more information please view Terms and Conditions for Buyers.

Sold for

£21,000

Starting price

£5000