Auction: 24003 - Orders, Decorations and Medals

Lot: 162

'The 5th Indian Division...had been overseas since August 1940 and had seen as much and as varied fighting as any Division. It had a spirit and self-reliance that came only from real fighting. It owed much to its commander, Major-General Briggs, and like all good Divisions - and bad ones - reflected its commander's personality.

The war had found him in command of a Battalion in this Division; a Battalion that in some extraordinary way was always where it was wanted, that always did what was wanted, and was ready to go on doing it.

So Briggs got a Brigade. His Brigade was just as steadily successful as his battalion had been. It went into the toughest spots, met the most difficult situations, and came out again, like its commander, still unperturbed and as quietly efficient as ever. So, while others fell by the wayside, Briggs got his Division.

I know of few commanders who made as many immediate and critical decisions on every step of the ladder of promotion, and I know of none who made so few mistakes.'

High praise indeed from none other than Field Marshal Sir 'Bill' Slim, a great advocate of Briggs

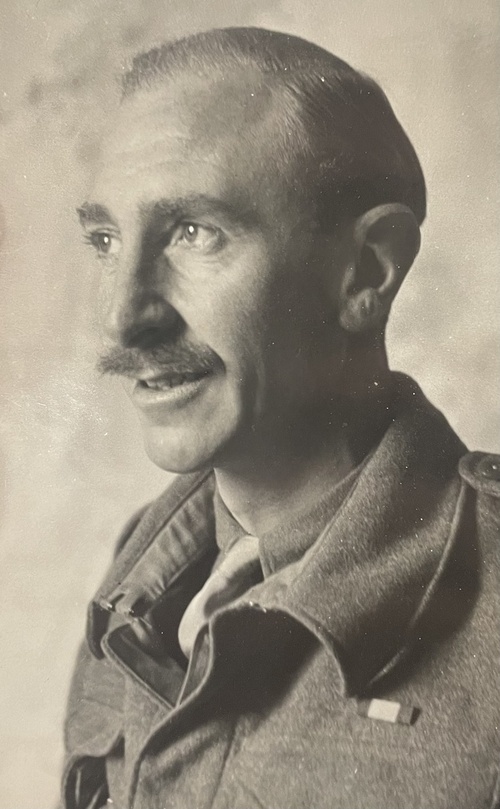

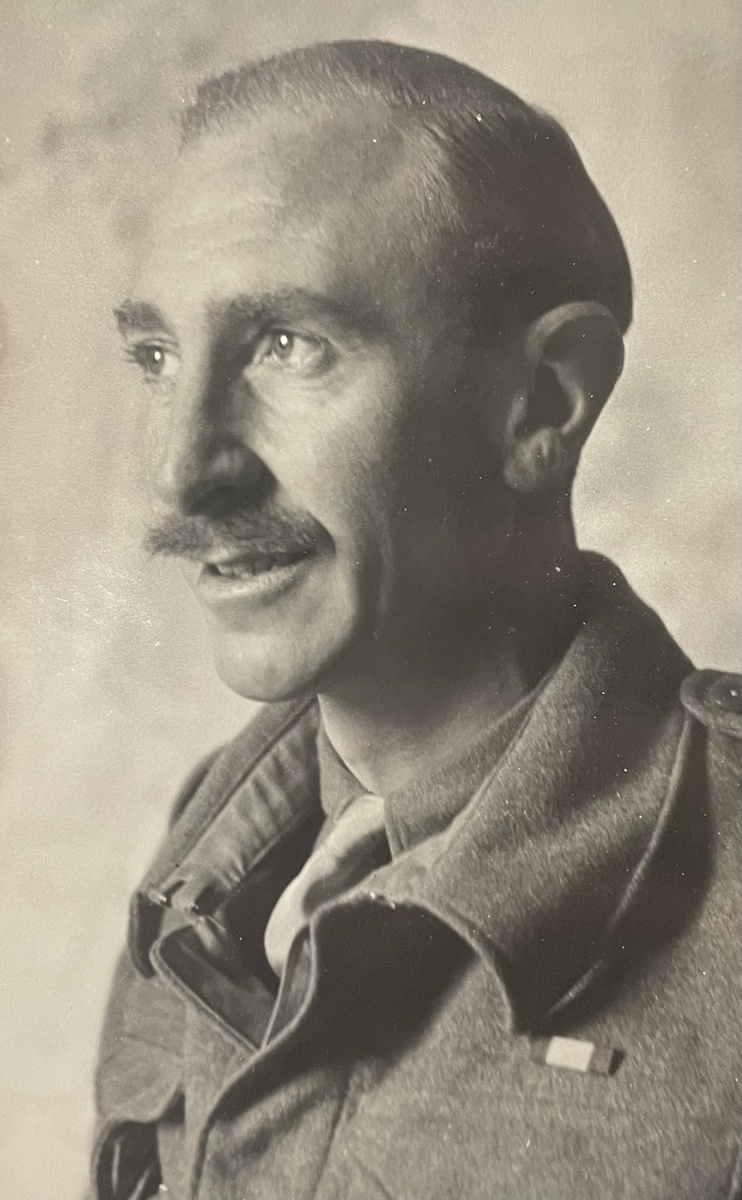

The remarkable '1950 Director of Operations, Malaya' K.B.E., '1948 Commander-in-Chief, Burma' K.C.I.E., 1946 C.B., D.S.O. and Two Bars awarded to Lieutenant-General Sir H. R. Briggs, Indian Army, who commanded the famous 5th Indian Division 'The Ball of Fire' from 1942-44

'Briggo' was a remarkable type who cut his teeth on the Western Front during the Great War - including being wounded in action - before earning a string of three Immediate D.S.O.'s during the Second World War - for Eritrea in 1941, for the Benghazi Breakout against Rommel's Force in 1942 and for Burma in 1945, during the famous actions in the Arakan and during the Admin Box Battle

He added the C.B.E. for good measure during the Siege of Imphal, when Messervy returned the favour of a good bottle of Scotch when their Divisions met on the Kohima Road on 22 June - one of the finest Divisional Commander's to serve the Allied Armies during the Second World War, Briggs also earned no less than four 'mentions' during his career, one in which 'Bill' Slim felt obliged to apologise for only being able to give him Immediate D.S.O.'s

The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire, 2nd Type, Civil Division, Knight Commander's (K.B.E.) set of insignia, comprising neck Badge, silver-gilt and enamel; breast Star, silver-gilt, silver and enamel; The Most Eminent Order of the Indian Empire, Knight Commander’s (K.C.I.E.) set of Insignia, comprising neck Badge, gold and enamel; breast Star, silver with gold and enamel appliqué centre, gold retaining pin; Distinguished Service Order, G.VI.R., the reverse officially dated '1941', with Second and Third Award Bar, these officially dated '1942' and '1944', top riband bar adapted for mounting; 1914-15 Star (2-Lt. H. R. Briggs, 31 Punjabis.); British War and Victory Medals, with M.I.D. oak leaves (Capt. H. R. Briggs.); India General Service 1908-35, 1 clasp, North West Frontier 1930-31 (Capt. H. R. Briggs. 1-10 Baluch. R.); 1939-45 Star; Africa Star; Burma Star; Defence and War Medals 1939-45, with M.I.D. oak leaf; Indian Independence Medal 1947, the early campaign awards a little polished, otherwise good very fine (14)

Just 59 awards of the Distinguished Service Order and Two Bars during the Second World War - 5 of these to the Indian Army during the Second World War - from a total of 140 made in the period 1886-1979.

K.B.E. (Civil Division) London Gazette 1 January 1952 (Director of Operations, Federation of Malaya).

K.C.I.E. London Gazette 1 January 1948 (General Officer Commander-in-Chief, Burma).

C.B. London Gazette 13 June 1946.

C.B.E. London Gazette 28 June 1945. The original Recommendation - for an Immediate award - states:

'Major General Briggs commanded 5 Indian Division from the time of its arrival by air in Imphal up to the close of the defensive battle and the launching of 5 Ind Div in pursuit of the Japanese on the Tiddim Road. During the battle he operated on three different fronts and handled all operations entrusted to his charge with determination and considerable tactical skill. His preparation for attacks was invariably good and undoubtedly saved many casualties. The successful operations in the Nunshigum area as well as those for the opening of the southern portion of the road Imphal-Kohima were due in no small measure to Major General Briggs's drive and tactical ability. He has once again proved himself to be a high grade commander and I consider his work merits recognition.'

D.S.O. London Gazette 30 December 1941. The original Recommendation - for an Immediate award for his command in East Africa of the 7th Indian Infantry Brigade - states:

'Brigadier Briggs commanded a force of all arms, comprising British, Indian, Sudanese and Free French Troops, which advanced, during the months of February and March 1941, from Port Sudan via the hills adjoining the Red Sea Littoral against Keren from the North. Owing to distance and difficulties of communication he had to operate independently, guided only by general instructions from HQ Troops in the Sudan. The country was mountainous and difficult with only one track for transport. The Force was based on the open beach of Merca Taclai devoid of any facilities, well over a hundred miles from the leading troops.

The advance was opposed by the enemy. In the vicinity of Cheren the force engaged as much as two Brigades of Italian troops that had to be diverted from the main front. The success of this force and its considerable contribution to the victory of Keren were due to the tactical ability, bold handling, energy and resource and administrative skill of Brigadier Briggs. Subsequent to the capture of Keren Brigadier Briggs' Force was moved to the plain of the Red Sea Littoral where it took a successful part in the capture of Massawa, again due to the ability of Brigadier Briggs as Commander.'

Second Award Bar to D.S.O. London Gazette 23 April 1942. The original Recommendation - for an Immediate award for the Benghazi Breakout - states:

'Brigadier Briggs was commanding 7th Indian Infantry Brigade Group at Benghazi on 28th January 1942. This Brigade Group was attacked firstly in front by Armoured forces and later by the 21st German Armoured Division on flank and rear. Brigadier Briggs throughout the day held off and beat back the frontal attack inflicting losses on the enemy and only giving ground under extreme pressure.

Towards dark the heavy attacks developed to flank and rear - in spite of the extreme gravity of the situation and the fact that his own HQ was attacked by tanks, by his skill in leadership, he managed to hold his ground outside Benghazi and so gained time for the evacuation of that place and completion of essential demolitions. Finally at night, realising that he was surrounded he at once ordered his force to break through the enemy's front and make for the Mechili area. He coolly organised this and carried it out, thus saving most of his Brigade Group. He himself led one column of the force 250 miles across the desert to Mechili.

This is one of the outstanding episodes of courage and leadership of this War and the facts are well known to all in the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force.'

Third Award Bar to D.S.O. London Gazette 18 May 1945. The original Recommendation - for an Immediate award for actions in the Arakan including the Relief of the Admin Box - states:

'For gallant and distinguished conduct at the battle of Ngakyedauk, Arakan, 4-26 February 1944. He was entrusted with the relief of the besieged 7th Indian Division and the re-opening of the Pass. He carried out these duties with skill and sound judgement. During the critical period when the enemy had taken Pt 1070 he showed determination under difficult conditions which resulted in complete success.'

A striking letter on this award came in from his great friend, 'Bill' Slim:

'My dear 'Briggo'

This is to congratulate you on the [Third Award] Bar to your D.S.O. Few have been better earned. It is not what the doctor ordered for you but it was the best immediate award that could be got. Anyway we can't go on giving you Bars to the D.S.O. I'll try for something else again next time.

5 Div as usual is more than doing its stuff - and it does get around, doesn't it. All the best to you and it and again my congrats.

Yours Bill'

M.I.D. London Gazette 5 June 1919 (31st Punjabis, Egypt Operations), 24 June (Middle East) & 5 August 1943 (Persia-Iraq) and 5 April 1945 (Burma).

Harold Rawdon Briggs - or 'Briggo' to his friends and comrades - was born on 24 July 1894 at Pipestone, Minnesota, United States to English parents who returned to England a few years after his birth. Thus young Briggs, who was educated at Bedford School and the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst, was an American citizen until receiving British naturalisation papers in 1914. He was commissioned into the 4th Battalion, The King's Liverpool Regiment and proceeded to France with them on 5 March 1915, serving alongside the Indian Corps. He shared in the attack on Hilltop Ridge which cost The King's Regiment 374 other ranks killed, wounded or missing, including 1 Officer killed and 8 wounded. Briggs was among the latter and his active service on the Western Front came to an abrupt conclusion. He had been in France and Flanders for just seven weeks.

Having recovered from his wounds, he was posted to India, proceeding to serve with the 31st Punjabis in Mesopotamia from 15 December 1915-May 1918. During this period he acted as Company Officer, Quartermaster, and officiating Company Commander.

From 21 May 1918-19 January 1919 Briggs was attached as a Company Commander to a new Battalion of a new Regiment just then being formed for service in Palestine, the 1/152nd Punjabis, taking with him a Company of Punjabi Mussalmen. Several months were spent in and out of the line in Palestine, then on 19 September 1918 the Battalion took part in an attack on Turkish positions at Tabsor village, which probably earned him his first 'mention'.

Second World War - opening shots

A Lieutenant-Colonel in command of the 2nd/10th Baluch Regiment and forty-five years in age at the outbreak of the Second World War, Briggs could not perhaps have expected the amount of experience he would gain in the coming years. He left his Regiment in August 1940 and assumed command of the 7th Indian Brigade. We can turn to the man himself for his views on this period:

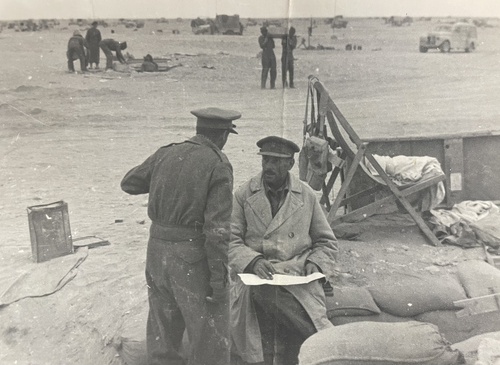

'"In September 1940 I was given command of the 7th Indian Brigade at Poona with orders to take it to join the 5th Indian Division in the Sudan. We left Bombay on 20th September in a large convoy, passing close to the coast of Eritrea, then in Italian hands and from which we were half-heartedly bombed from a great height. During the voyage our orders were changed and we were now to become the third brigade of the 4th Indian Division (General Beresford-Peirse) then in the Western Desert Corps (General O'Connor).

The Brigade concentrated at Mena in Egypt for equipping and training and I went up to report to the Division, which I found preparing two positions at Sidi Haneish and Bagush. In front of this were located the 7th Armoured Division, based on a composite garrison at Matruh. The Italians, about 300,000 strong, had just crossed the Egyptian frontier to occupy forward positions around Sidi Barrani, Sollum and Bardia. The enemy air force was very active and had air supremacy.

The General took me into his confidence as to future plans. General Wavell, Commander-in-Chief Middle East, intended to transfer 4th Indian Division to the Sudan to make a lightning attack on the Italians there, who were threatening an invasion. We were to reach there in early January 1941 on being relieved by an Australian Division. Prior to this, however, the Desert Corps was to make a heavy raid on the Sidi Barrani positions to delay their advance. If this raid was highly successful, the Australians would be in a position to exploit it.

In October, 7th Brigade joined its division at Bagush. The Brigade Group was composed of: Headquarters, Brigade Signal Section, 1st Bn Royal Sussex Regiment, 4th Bn 11th Sikh Regiment, 4th Bn 16th Punjab Regiment, 25th Regiment Royal Artillery, 4th Indian Sapper and Miner Company, 17th Field Ambulance and ancillary units.

On 8th December the expected attack was launched, after a previous rehearsal on full-scale model camps. 7th Brigade was given the task of forming a screen in No-Man's-Land to protect the deployment and through which the attack would pass; finally, to act as reserve.

The Italian dispositions are shown on the sketch and each one was in the form of a perimeter camp and walled - very unsuitable to modern armament. Nor were the camps, in all cases, inter-supporting. Our plans were based on the invulnerability of our Infantry Tanks (Matildas), a close follow-up by infantry in lorries, concentrated artillery support and surprise. Thanks to a dust storm and temporary air mastery surprise was complete throughout the one hundred mile advance. Whilst 7th Armoured Division held the ring, 11th Infantry Brigade captured Nubeiwa from the rear followed by the capture of Tummar West and East by 5th Infantry Brigade. 16th British Brigade (whom we were relieving in 4th Division) turned to the capture of Sidi Barrani. The rout was complete. 4th Indian Division captured 20,000 prisoners, tanks and much equipment. 7th Armoured Division, hard in pursuit and followed by the Australians, were finally to capture Benghazi. 7th Infantry Brigade, which had hoped to be in the battle, was by now en route for the Sudan, which it reached by 1st January.'

He would earn his first D.S.O. for the campaign in Eritrea, Asmara in early 1941 with 'Briggs Force':

'7th Infantry Brigade arrived at Port Sudan on 1st January 1941, to find that, instead of going straight into action, we were to relieve a brigade of 5th Division on protection duties at Port Sudan and on the Lines of Communication. The Sikhs joined 4th Indian Division on its arrival and the Punjabis moved to Khartoum and Senna. Our artillery was with 4th Indian Division. Brigade Headquarters and the Royal Sussex were ordered to bluff the enemy into thinking that at least a division was about to advance onto Massawa, thereby dissuading the Italians from attacking Port Sudan and drawing reserves into the coastal area. This was done to such effect that our ten carriers were reported as forty tanks and the dummy port construction at Aqiq, dumps of empty tins, tents etc. nearby received heavy attention daily from the air.

The situation at this time was that the Italians had invaded the Sudan and captured Kassala and it seemed likely that, having captured British Somaliland and freed their reserves, the capture of the Sudan was imminent. The active deep patrolling of 5th Indian Division and the enemy's bad appreciation of our pitifully slender strength had begun to make them nervous. As pressure was intensified by the arrival of 4th Indian Division, the Italians decided to withdraw into the hills towards Keren before our planned attacks could materialise. Their withdrawal was followed up so closely by both divisions that many thousands of troops were cut off and much equipment captured. Had the Italians not been so clever at demolitions it is quite possible that their occupation of the reputedly impregnable position of Keren might have been too late. 4th Indian Division in its efforts to capture it quickly, suffered very heavy casualties and it was found that Italians, especially their colonial troops, fought very stubbornly unless one could get in behind them, which in this case was impossible.

The Keren heights averaged 7000 feet above the plain and the roads and railway zigzagged up the passes. The hills were steep and the approaches often razorbacked and bare. Troops reaching the summit were met by a shower of Verey light grenades which exploded on percussion, causing bad wounds.

During this phase it was put to me that I should consider the possibility of making a landing from the sea thirty miles north of Massawa with two Sudanese Motor Machine Gun Companies, two squadrons of tanks and two Commandos, to be followed two days later by my Brigade. With this object in view I proceeded on a bombing raid on Massawa and flew at 2000 feet receiving much attention from anti-aircraft fire. I accepted the task though reporting on it as risky. Events, however, made the attempt unnecessary.

Having realised the strength of the Italian Army and of the Keren defences, General Platt, the Commander-in-Chief, asked 7th Brigade to take on the task of advancing along the Red Sea coast onto Keren with a view to drawing off some of the enemy divisions from the main front. For this advance I would be given a Free French Senegalese battalion about to arrive from Chad at Port Sudan, a battalion of the Foreign Legion due later, the 1st Bn Royal Sussex Regiment, 4/16th Punjab Regiment, 25th Field Regiment Royal Artillery, a Sudanese Motor Machine Gun Company, 20th Sappers & Miners and a Transport Company, all of which were south of Khartoum and had to be brought by rail to Port Sudan. In spite of the necessary delay in collecting these, could I please HURRY?

The situation opposite me was that an Italian brigade, which had been located in the area Elghena-Karora-Mersa Taclai had been lately thinned out to an estimated strength of one battalion whilst at Kubkub a second battalion was known to be located, covering the Keren approaches. The greatest obstacles to the advance were the roads between Suakim and Elghena, which were almost obliterated by sand dunes and almost impassable for heavily laden lorries. There were no telephones back to our base of Port Sudan and such wireless sets which we had were not constructed for such long distances. The distance between there and Keren was over 200 miles. However plans were already made for the capture of Elghena by the Royal Sussex (Lt Col Eadie) in the shape of taking Karora and Mersa Taclai with turning movements behind them, thereafter converging on Elghena. At Mersa Taclai there was a completely silted up rowing boat harbour, in which by sinking a lighter we might make a pier for local dhows in fair weather. It was hoped that our Lines of Communication might be possible through this. We immediately took steps to commandeer every available dhow in the Red Sea and I obtained the loan of the Royal Indian Navy sloop the Ratnigiri.

The capture of the Frontier posts went off as planned with few casualties and with the capture of 300 Italian Colonial troops, who were immediately put on to constructing the harbour and a road to Elghena through terribly heavy sand - so heavy that diversions had to be made almost daily. Within four days of receiving our orders the Chad Battalion was landed at Mersa Taclai and sufficient lorries sent there empty to move two companies towards Kubkub in the wake of the Carriers and one company of the Royal Sussex. They discovered a very strong enemy position among steep hills and protected by mines. Within two days this position had been reconnoitred and the whole of the Chad Battalion had been ferried up. No further reinforcements had as yet reached Port Sudan and we only had such stores as the troops could take with them. Petrol tins had to be floated ashore at Mersa Taclai.'

They advanced onto Kubkub, Mount Engahat and then took Massawa:

'7th Brigade was now ordered to concentrate on the coastal plain and capture Massawa. To do this it was essential first to cut the Massawa-Asmara road. This the Foreign Legion accomplished capturing 1500 prisoners. This success and the fall of Asmara without opposition persuaded the Commander-in-Chief to send a brigade of 5th Division with tanks and artillery to make a joint attack with us on the town. Within six hours of our launching our combined attack Massawa surrendered. The race for the town was won by 7th Brigade by a matter of minutes. We captured 11,000 Italians and very many guns, but the enemy had scuttled all his ships in the harbour.

By this time a disastrous defeat had occurred in the Western Desert and 4th Indian Division was already on its way back. We were to follow. Keren had fallen on 27th March and Massawa twelve days later. It may be claimed that by this date the Italian Empire had ceased to exist.'

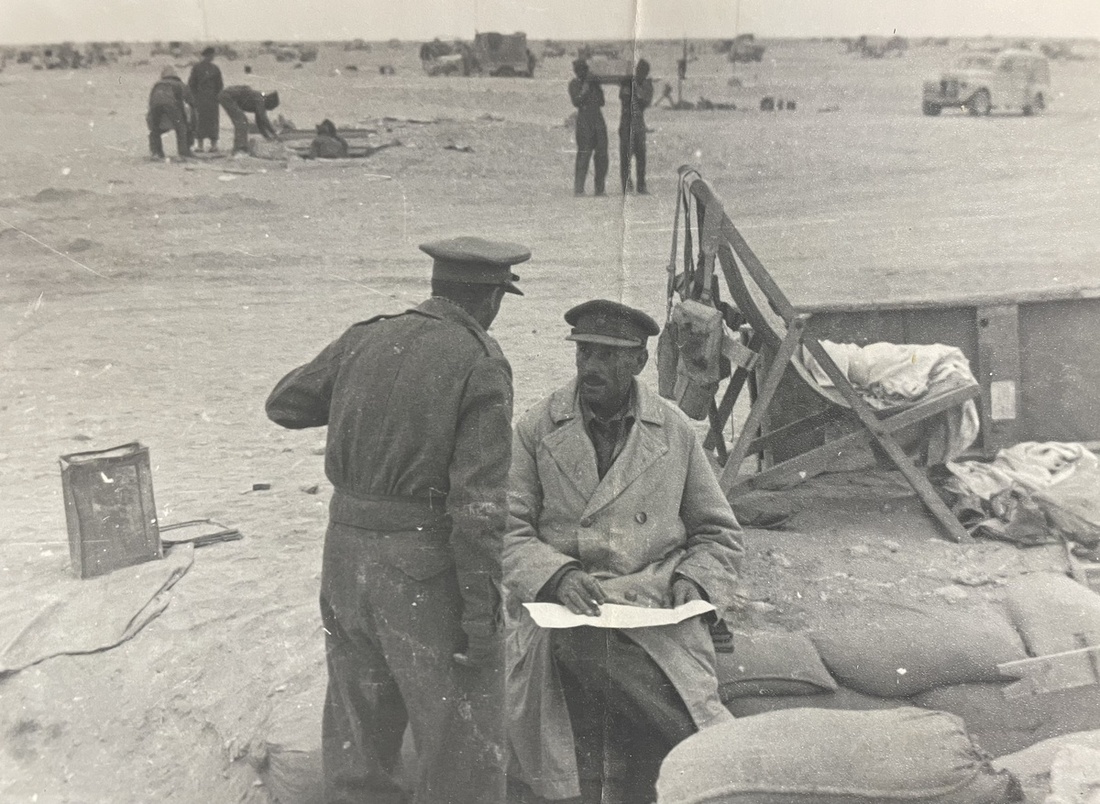

Western Desert - Bar to D.S.O.

After a short rest, his Brigade were then called up to press on with Op Crusader:

'On 18th November 1941 the offensive started with an advance by 30 Corps, consisting of the Armour and 1st South African Division, onto Tobruk and together with its garrison search out the enemy and destroy his Afrika Korps. 13 Corps, consisting of the New Zealand Division, 4th Indian Division and 1st Army Tank Brigade was to protect the Lines of Communication and isolate the enemy Frontier defences. Of 4th Indian Division's three brigades, 5th Brigade was still out of action, 11th Brigade was deployed on the coast opposing Sollum, which left 7th Brigade to deal with the Omar positions along the frontier wire. The New Zealand Division moved round behind Bardia and Gambut.

The first orders which 7th Brigade received were to mask Cova with one battalion (the Sikhs) and Libyan Omar from the south-east and north-west until the result of the armoured battle became clear. As this appeared at first to be going well, 7th Brigade was ordered to attack and capture the positions of Libyan Omar and Omar Nuovo whilst still masking Cova from the south. We were to be supported by 42nd Battalion Royal Tanks and the Divisional Artillery. Surprise was by now impossible, but reconnaissances proved that the Germans were feverishly mining the north of their positions and it might just be possible to attack before Omar Nuovo was completed.

My plan was for the Royal Sussex to attack Nuovo from the north with two squadrons of tanks in support. They were to approach the minefield in their lorries, debus close up behind the tanks and rush the position. The time chosen was mid-day to take advantage of the heavy mirage. Behind the Royal Sussex would be Brigade HQ, closely followed by the reserve tank squadron and the 4/16th Punjabis. Once Nuovo was taken this latter battalion was to swing towards Libyan Omar after passing through the minefields, and capture that position. The concentrated fire of the artillery would cover each advance.

The dash of the Royal Sussex was magnificent and, though only 400 strong, they had succeeded in capturing all their objectives including 2000 Germans and Italians and much equipment. The 4/16th were then launched onto Libyan Omar, where they succeeded in penetrating the position deeply.

Unfortunately darkness overtook them before their task was completed and they were swamped by the mass surrender of about 1500 Italians. At nightfall a strong force of Germans and picked Italians remained to be attacked. The infantry casualties were fairly heavy but the losses of tanks from 88-mm guns in Libyan Omar, which then remained intact, was serious as, to avoid these, the tanks ran onto a minefield on their flank. It was to be a week before this enemy pocket was eliminated as our attention was directed elsewhere.

Meantime, further west the 8th Army had had a serious reverse. The 5th South African Brigade had been destroyed and the 7th Armoured Division had suffered serious losses. Rommel then turned onto the communications of the Armour. This course would have been as effective as beating them in battle, had he still got control of the Frontier defences, but our possession of Omar Nuovo made a route for our supply vehicles still possible though much confusion had already been caused among them. The first intimation we had of Rommel's presence was a report from 7th Brigade rear echelons that enemy armour had captured our Field Ambulance, where their wounded were receiving attention, and that they were thus halted for the night within one mile of them [the rear echelons] at Bir Shefersen. Orders were immediately sent to this echelon to close into the Omar defences.'

Desmond Young comes in:

'In the twilight of that winter evening I walked over the battlefield with Brigadier H.R. Briggs. I saw a sad number of our dead, but never one who had not fallen with his face to the enemy. Action had ceased but a sniper was paying us some attention, and a machine-gun was firing at close range. 'We must get those birds out before dark,' said the Brigadier.

Two tanks were despatched to sweep the ground with infantry accompanying them. In the dusk their tracer bullets splashed red and green against the apparently deserted trenches. Then came the bright yellow crashes of grenades thrown into dug-outs by the Royal Sussex. Back came the tanks with their tails behind them - tails of two hundred more prisoners who trudged in as night fell.'

After the action on the Jebel in December 1941, one of his finest moments must have surely been the part in the Beghazi Breakout in early 1942 played by his Brigade in the way they smashed Rommel's force. It earned the Bar to his D.S.O. and the reader is implored to study this action further, various excellent sources exist, including the Official History The Tiger Kills. Briggs again:

'It was now decided that 4th Indian Division should be given the chance to refit and rest and that 5th Indian Division should replace them. Little did I realise that, within six weeks, I should return to command 5th Indian Division in the same area of the desert.

7th Brigade moved to Cyprus, where I found myself commanding the island, taking over from General Mayne, who was moving out with 5th Division. During my five weeks in Cyprus I had to attend discussions in Cairo on action in case the Germans invaded Turkey. Also I had to convert the defence plans of the island to plans against a sea landing as opposed to an air landing only.

On my departure I was sad at having to say 'good-bye' to all my comrades in 7th Brigade, who were later to earn still further laurels from Alamein to the capture of Italy.'

Ball of Fire

Briggs now took on command of the 5th Indian Division (also known as the 'Ball of Fire Division' - and to others less polite, mainly in other formations, as the 'flaming arsehole') in Army Reserve at Sollum, on the Egyptian side of the 'wire,' in early May 1942:

'Rommel's initial advance onto El Adem was however held up and it appeared that, his petrol being exhausted, he would suffer a serious loss of tanks many of which were already stranded and destroyed, but he made a bold move in occupying an undefended part of our minefield, afterwards known as the 'Cauldron,' from where he opened up a supply route back to Tmimi. Rommel, from this position struck at and over-ran one brigade position of 50th Division to the north, then began to turn his attention towards Bir Hakeim. This is the essence of good tactics with an armoured formation, viz, to use your armour for manoeuvre to capture a feature which you can make so vital to the enemy that he must attack you. When he does, he meets an anti-tank gun, infantry and artillery screen, behind which your armour is free to manoeuvre in safety. This is what happened here and why we lost so many tanks and with them the battle.

There was, however, another answer, which was to cut Rommel's communications between the Cauldron and Tmimi, preferably by 50th or 1st South African Division.

The first suggestion put was for 5th Division to be collected at speed, formed up behind the South African Division and attack through the South African Division to capture Tmimi itself. To do this satisfactorily over ground unknown to us and against a mined position defended by one German infantry division and half an armoured division - all within thirty-six hours - seemed to me too costly and unlikely to succeed. I countered this with a proposal that the South African Division, who knew the ground well, should carry out the attack, whilst we took over their defences or, preferably that I took 5th Division by the desert, which I knew well, south of Bir Hakeim and, retaining my mobility, attacking Tmimi and Rommel's communications west of the minefields. I asked that our armour should protect my right flank from Rommel's tanks. This latter plan was agreed to and was being put into operation, then without consulting me it was changed and the fatal plan was adopted.'

The deployment of Briggs and his command into 'The Cauldron' has forever drawn raised eyebrows and even the enemy thought it strange. The disaster which follows cannot be attributed to Briggs:

'In this new plan 10th Brigade was relieved in its position and was to make a night attack to capture and hold the 'rim' of the Cauldron, three miles west of Knightsbridge. This under orders of 5th Division. It was successful against Italian opposition. From then on the whole operation was placed under 7th Armoured Division. Whilst 2nd Armoured Brigade was to remain to protect our left flank, the 4th Armoured Brigade, supported by 9th Brigade was to pass through 10th Brigade and engage Rommel's armour. They met, as must have been expected, heavy artillery and machine gun fire and were forced to withdraw with heavy losses in tanks. The enemy tanks followed up the withdrawal, penetrating into the position of the Highland Light Infantry of 10th Brigade. Here they were halted and a long range tank duel took place, much to the advantage of the German tanks with their heavy armament. Worse was however to follow. The commander of 7th Armoured Division [Messervy] ordered, not only all the artillery of both divisions up into the battle, but also the 2nd Armoured Brigade, thus exposing our left flank.

The enemy tanks, moving behind the minefield appeared at the Bir El Harmat gap, broke through its garrison, now bereft of artillery, and came in from the left onto 10th Brigade's headquarters and the tactical headquarters of 7th Armoured and 5th Divisions, finally to surround the whole attacking force, dividing them from their ammunition reserves. The tank brigades were able to extract themselves but not so the infantry and artillery, who had to fight it out.

Meanwhile, by a lucky chance, I had gone forward on a reconnaissance of the battle area and found a terrible collection of massed lorries, guns and tanks. I decided, without referring to 7th Armoured Division, to withdraw 9th Brigade out of the battle, where they were being heavily 'Stukaed' and shelled to no purpose. They thus escaped destruction, which fate befell the rest of the force, including 10th Brigade and all the artillery, after fierce resistance but without support. I returned to my tactical HQ, quite unaware of the course events had taken, to find it occupied by enemy tanks. These chased me for many miles but I succeeded in reaching my main HQ safely.'

They were then asked to stand and give it to Rommel:

'On 5th July HQ 5th Division moved into the area with 9th Brigade, who had to be re-equipped and brought up to strength. A few days afterwards we received as reinforcements 5th Indian Brigade of 4th Indian Division. By 14th July I was ready to start offensive operations and that night 5th Brigade stormed the main feature, Point 64, of the ridge. Two battalions of the Brescia Division were overrun and 1000 prisoners taken. Next evening the expected counter-attack of Rommel's tanks arrived, but we were ready for it. By this time a brigade of our tanks had arrived and were located 'hull down' behind our position. The enemy attack failed miserably and daybreak found derelicts strewn over the ground, including twenty-four tanks and six armoured cars. On 19th July, 9th Brigade was launched and captured a further 3000 yards of the ridge, but it was noticed that by now the Germans' position had strengthened greatly and spasmodic attacks were likely to become more costly. Reports kept coming in that the Germans were exhausted and suffering from water shortage. This persuaded General Auchinleck to try one more strong attack along the ridge together with an attack by the New Zealand Division with armour on our left. This failed owing to stiffened defences and lack of time for preparation. Thereafter there was a temporary stalemate on the front whilst each side re-organised and awaited reinforcements.

Owing to Rommel's access to all the captured supplies at Tobruk it was realised that he would be able to attack first. In fact he was so confident of capturing Egypt that Mussolini came over to make an official entry. At this moment Churchill arrived in the Desert and arranged for Generals Alexander and Montgomery to take over the Middle East and 8th Army respectively. The latter immediately changed certain aspects of General Auchinleck's plans for defence, which were to have a great bearing on Rommel's defeat. Anticipating that Rommel would attack round the south as usual, he asked for and received 44th British Division, which was just disembarked, to occupy a position facing south behind which he placed our tank force with orders that the enemy tanks must be made TO ATTACK US. Only if the enemy tried to bypass our position and strike at Egypt were our tanks to engage him and his communications. At last we had learnt our lesson as to how to employ armour.

Rommel made his great bid on August 30th. He ran into an inferno of gunfire at the expense of sixty of his tanks and 600 vehicles. He withdrew slightly in the hope that our tanks would charge his guns in their turn but this was not permitted and he suffered such heavy and continuous bombing from our Royal Air Force that he finally had to withdraw and his last bid for Egypt was abandoned. During this battle the Germans launched an auxiliary attack onto 5th Division on the Ruwaisat Ridge, the forward end penetration was made but in anticipation of this I had the Essex Regiment of 5th Brigade and a squadron of tanks previously rehearsed in a counter-attack role who dislodged the enemy before dawn.

At this period the German forces in Russia were threatening an invasion of Persia and PAIFORCE was being formed in Persia and Iraq. This coincided with a demand by 4th Division to get its 5th Brigade back again. It was therefore decided that 5th Division should be relieved by 4th Division in the desert and that 5th Division should move to Iraq. This took place on 9th September 1942.'

Having managed to come out of it somehow, they fell back to El Alamein and were relieved in their positions on Ruweisat Ridge by General Tuker's 4th Division. They went as part of PAIFORCE from September 1942-April 1943 and then moved to India from June-September 1943.

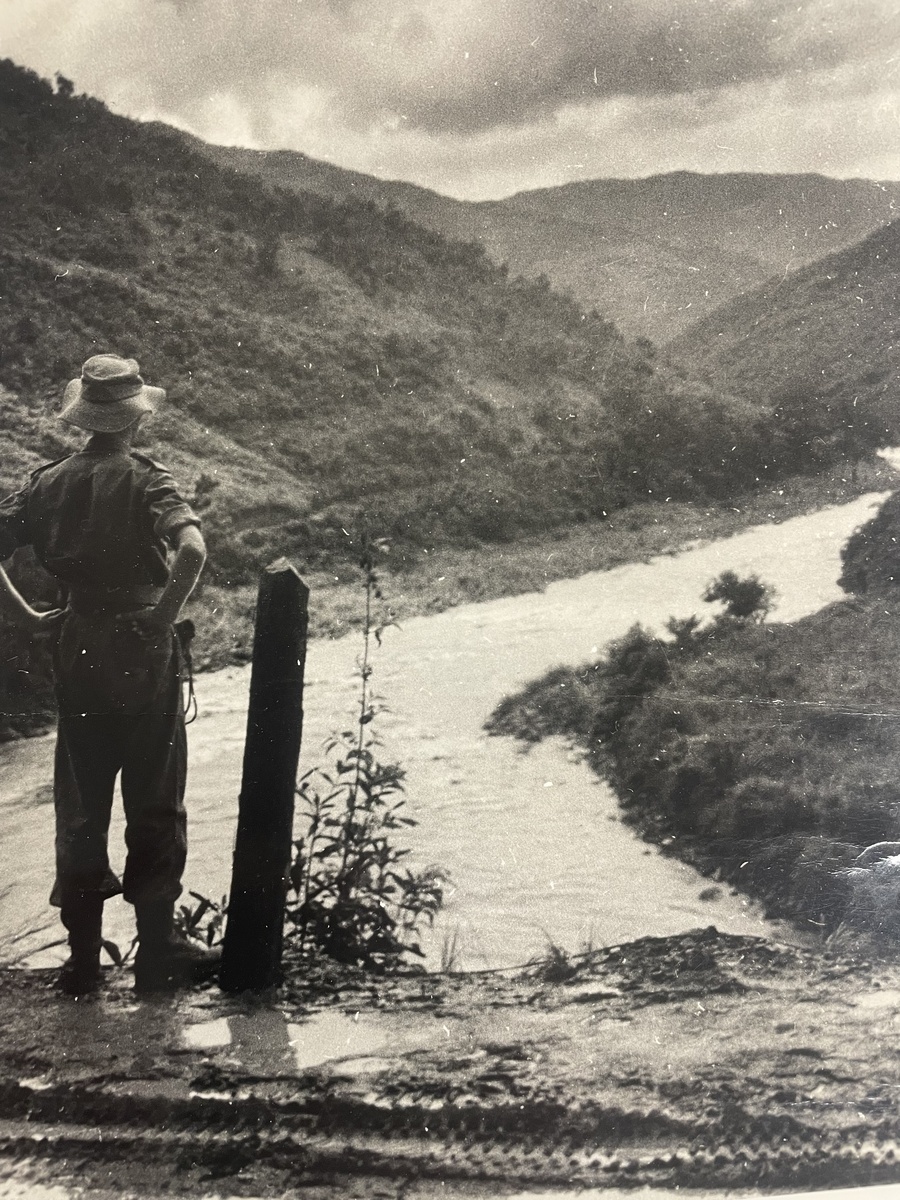

Arakan - Third D.S.O.

Together with his Division, the gallant band gave invaluable service in Burma from October 1943-March 1944:

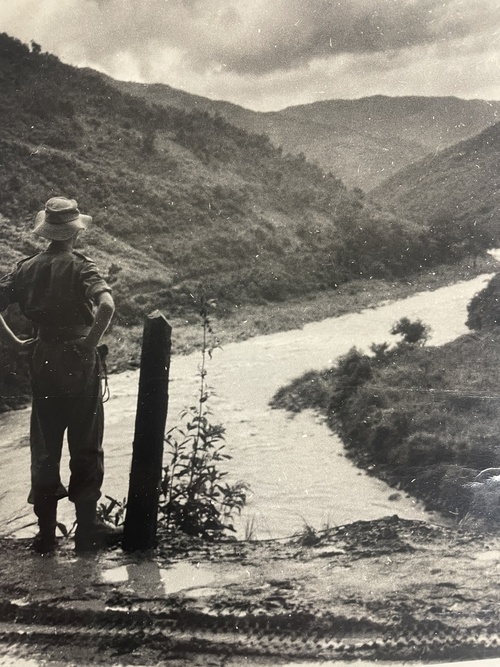

'5th Indian Division headquarters, 123rd Brigade (Winterton) and 161st Brigade (Warren) arrived in the Arakan in October 1943 and during November 123rd Brigade took over the front opposite the Japanese who were occupying the area of Maungdaw-Buthidaung. Operations for the winter 1943-44 were for 4 Corps primarily to hold the Imphal area whilst 15 Corps attempted to clear the Arakan and capture Akyab. This was modified to an advance as far as Rathedaunge owing to the lack of landing craft which were intended to enable a further landing on Akyab Island.

The first objectives of 15 Corps were the capture of Maungdaw and Buthedaung and the Tunnels area between these two places. This position was known to be held by the Japanese 54th Division and to be very strongly fortified. 55th Japanese Division was known to be in the area of Indin-Akyab. A Japanese cavalry regiment was also located near Paletwa on the Kaladan river. To deal with this latter and to protect the Corps left flank 81st West African division was to move via Mowbok onto Paletwa and Kaladan. This division had 'porters' as supply carriers and would be supplied by air.

The main Corps thrust was between the Naf and Kalapanzin rivers with 5th Indian Division on the right and 7th Indian Division (Gen Messervy) on the left. Between the two divisions and parallel to the line of advance lay the Mayu Range approximately 3000 feet high and very thickly treed. On each side of this range were very densely bushed low hills whilst near the rivers were rice paddy fields interspersed with tidal 'chaungs' or inlets. It was in these low hills that the Japs had their strong defences, as also on the top of the Mayu Range itself. The crest of the Mayu Range was made the responsibility of 5th Indian Division.'

They then came to the fore in the Battle of Admin Box:

'As soon as I had appreciated the situation I had to act quickly. In the hope of preventing the Japs cutting the Ngakedauk Pass I ordered the reserve battalion of 9th Brigade on the other side to move back to the eastern end to engage the enemy. This arrived too late but it reached the Admin Box in time to save it. This battalion, the West Yorkshires, acting directly under Brigadier Evans, was the only fighting formation in the neighbourhood. He performed up to three counter-attacks daily to counter Japanese penetration. Later 25th Dragoons and 7th Division's reserve brigade were called in also.

To the west end of the pass I ordered my on my reserve battalion, but only half were available as Corps Headquarters asked for the rest to prevent enemy crossing the Goppe Pass into their headquarters near Bawli. This battalion succeeded in reaching the top of the pass and holding it securely.

I then had to collect in another battalion to clear the Bawli-Maungdaw road. This was accomplished though the Japanese remained in the Mayu Range behind me. Next day these rear commitments were taken over by elements of 26th Division brought up from Cox's Bazaar. My own supply position was secure as I was using marine transport in the Naf River. I had however to lay on air supply details for the whole of 7th Division as their wireless sets were captured when their headquarters were overrun. I alone had communications by wireless with General Messervy through the 25th Dragoons. 7th Division's casualties were mounting up and my old Desert comrade was in trouble so some risks had to be taken to open the pass to his relief. I decided to thin out my front to the strength of one brigade and collect together a striking force. The main strength of the Japs was on Hill 1070 in the middle of the pass. This was captured, lost, recaptured and finally completely encircled through very dense jungle and captured after very tiring and stiff fighting.

There were still two more strong hills to capture, one Sugar Loaf which dominated the Admin Box. This task was given to the 1st Punjabis, who made a surprise move round the north and with most effective air support were completely successful. Troops from the Admin Box cooperated and the enemy fled from the pass back towards the Tunnels, hundreds being trapped by our forward battalions and our artillery on the way back. Except for snipers, the pass was open, and these were quickly put out of action. Much joy was expressed when I arrived in the Admin Box in a tank with some whisky and certain toilet articles for Messervy and Evans. That day we had evacuated all the casualties from the box.

Shortly after the relief 26th Division, which had been driving down from the north, also made contact and the Japanese were in full retreat. This was the first Japanese defeat in Burma and was to be followed by many more.'

It is no surprise Briggs took his third Immediate D.S.O. and further admiration from 'Bill' Slim.

Imphal - C.B.E.

As the pivotal campaign in Burma moved on, the Siege of Imphal saw Briggs take further laurels:

'On arrival at Imphal I found the situation as follows: General Mutaguchi, the Japanese Army Commander planned to cut all our communications to Imphal (Kohima Road and Bishenpur Track to Silchar), hold off reinforcements by capturing Kohima, capture the Imphal plain and, using captured British equipment, invade Assam and Bengal. The moves of Japanese 15th, 31st and 33rd Divisions are shown on sketch.

It was now mid-March 1944 and to meet this threat, 20th Indian Division was ordered to withdraw to south of Palel and 17th Division from Tiddim to the entrance of the Imphal plain towards Bishenpur. Orders for the latter were received too late and the road was cut near the Burma Frontier. 17th Division had to fight hard to get through and 23rd Division had to move out to its assistance. At this moment too, 50th Parachute Brigade had just been overrun at Ukhrul to the north-east by the Japanese 31st Division.

I found that 123rd Brigade, which had preceded me, had been ordered to recapture Ukhrul. This seemed to me to be asking for its being surrounded by having its communication cut with Imphal, so I cancelled these orders except to send one battalion to help 50th Brigade's transport back into Imphal. I ordered the Brigade to prepare a position on dominating features just inside the plain, where water was available and round which it could use its tanks and artillery to the best advantage.

The second Brigade to arrive (161st under Warren) was diverted to Kohima to help the Assam Rifles to stem the Japanese advance. Here it fought an epic defence, although when it arrived the dominating features were in Japanese hands. It held firm to be joined later by 33 Corps (General Stopford) with 2nd British Division and later again 7th Indian Division, under whose command it came.

By the time 9th Brigade (Salomans) arrived, 123rd Brigade was heavily attacked on the Ukhrul Road. It inflicted heavy losses on the Japanese who withdrew from the plain. It was necessary to deploy 9th Brigade on a very broad front where it could only hold the most vital hills and operate mobile and with tanks on both sides of these. The first attack came down both sides of the Iril valley from the north. Though one hill (Nunshigum) was captured it was retaken next day, the tanks assisting by climbing 2000 feet to the crest. This tank regiment was the 3rd Carbineers...

The next threat was already developing down the main Kohima road. When I arrived in Imphal I found numerous administrative units strung along this including two General Hospitals. These I ordered-in quickly but there was left the main ordnance dump with a perimeter of nine miles and guarded by numerous untrained personnel. We succeeded daily in clearing the war-like stores and closing in the perimeter, but finally the Japanese succeeded in penetrating the dump at night. Next morning the West Yorks with tanks drove them out, but it was then time to evacuate the dump altogether and withdraw closer into the plain. The only items left for the Japanese was clothing, which they found better, and perhaps cleaner, than their own.

17th Division (General Cowan) succeeded in reaching Imphal and was located on the north front, one of his Brigades taking over the local defence of the Kohima road. This freed a portion of 9th Brigade and permitted us to turn to a limited defensive in the Iril valley and the Ukhrul Road, along both of which we forced the Japanese to withdraw some miles until the pre-monsoon rains made it impossible to maintain more than one battalion in the Iril valley.

The higher command now planned to take to the offensive. 17th Division commenced operations down the Tiddim road, 23rd Division from Palel, 20th Division took over the Ukhrul road and 5th Division the Kohima Road and Iril valley. At last 123rd Brigade (Evans) was released and in addition I was lent 89th Brigade (Crowther) of 7th Division to replace my 161st Brigade which was under 7th Division at Kohima.

I was permitted to take the offensive towards Kohima. I formed a secure base with 89th Brigade, one of whose battalions were however to operate deep up the Iril valley against the Japanese communications using air supply. This battalion's (Sikhs) efforts were magnificent and most successful, causing much disruption amongst the Japanese.

9th and 123rd Brigades, operating in depth, seizing vital features behind the enemy with air supply and forcing the Japanese to counter-attack with losses and then withdraw, advanced steadily until the enemy gave up even trying to counter-attack. He just withdrew, suffering casualties as he did so. We had as good as got him routed when news came that the Japanese at Kohima had withdrawn and a mobile column of 2nd Division was moving rapidly towards us. We met at the 109th milestone and the siege was over.

Our fighting on the Imphal plain was not yet over. It was now June 1944 and the Monsoon had been with us for over a month. 17th Division were in trouble with 33rd Japanese Division which had bypassed Bishenpur and threatening 17th Division's communications. 17th Division were fully deployed. We offered to help by clearing the Japanese off the high hills above Bishenpur. These were hidden in cloud and the troops found it difficult to keep touch. The Japanese, who were in effect covering the withdrawal of their 15th and 31st Divisions, refused to meet us and withdrew - sometimes quicker than they hoped. Once we were astride the Bishenpur-Silchar Track I offered to take on the pursuit. 17th Division did their last attack in the plain at Pots and Pans (easier than the real name: Postangam) and won a final victory though costly to both sides. We carried on the pursuit, the enemy withdrawing from the plain along the Tiddim Road.

Knowing that we were to stop under orders of 4 Corps at the 49th milestone, I decided that I was getting rather stale after four years hard fighting. I alone had had no break since the beginning of the war. I voiced this to General Scoones, commanding 4 Corps. This coincided with a request from Field Marshal Auchinleck for me to take over Ranchi training district in India, where 200,000 troops were training and refitting, including 30,000 Chinese under American instructions. I accepted and although sorry to leave such a wonderful Division after all these campaigns, I felt that I was right. I was able to hand it over to someone worthy of it in the shape of General G.C. Evans, who had served with me in 7th Brigade and in command of 123rd Brigade, and had meanwhile spent one year as Commandant of the Quetta Staff College. He possessed two Bars to his DSO.

5th Division was to perform a magnificent advance to recaptured Tiddim and drive the Japanese across the Chindwin. Later it was to advance through Burma to Rangoon. The first to land in Malaya and finally to occupy Java until empire troops were withdrawn in 1947. A really wonderful record!'

In a touching moment, when the 5th & 7th Indian Divisions met on the Kohima Road on 22 June:

'Messervy was quite delighted when he was able to signal the raising of the siege of Imphal in an exactly similar way to Briggs's gesture at the end of the battle of the Admin Box. He went through in a tank to the HQ from which Briggs had directed the fight-out of his men, emerged grinning from the hatch with a bottle of Scotch in his out-thrust hand, and called cheerfully: 'Here you are, Briggo. I'm returning the compliment'.'

It had been a remarkable few years and the Divisional Historian summed it up:

'General Briggs asked for a rest... Having had no break since the beginning of the War. General Auchinleck had asked for either Messervy or Briggs to command Ranchi area, the training ground for Burma... Briggs accepted the new post... If ever a man deserved a rest, it was Briggs, but for the Division he had led for two years in Desert and Jungle his departure was a tragedy...He did his best to say farewell, but as he fumbled for words I thought of four speeches that he might of delivered; yet what did it matter, for he was departing, and we were sorry, because we liked him much, he was a very good General.'

Journey's End - a brace of 'K's'

In January 1946, Briggs was made General Officer Commanding-in-Chief, Burma Command, with his Headquarters at Command House in Rangoon. That posting was certainly a tough one, the nation was attempting to recover from the ravages of the Second World War and unrest bubbled just below the surface. Reconstruction, maintenance of order and protection of borders all at once required serious effort. Briggs added the C.B. in the summer of 1946 and was made K.C.I.E. upon retirement, after what was another draining posting and headed for Cyprus. It was only to last two years.

With the outbreak of the Malayan Emergency, it is fair to say the the response of the British Government and its troops and the Federation of Malaya was far from clear. Briggs found himself appointed as the civilian Director of Operations, a co-ordinator under civilian control. He landed into Kuala Lumpur on 5 April 1950 to prepare and deliver the 'Briggs Plan' for the prosecution of the conflict. Sir Robert Thompson continues:

'Briggs hardly altered a word, particularly in the statement of four vital suggestions for conducting the war:

(a) to dominate the populated areas and to build up a feeling of complete security therein which will in time result in a steady and increasing flow of information coming in from all sources.

(b) to break up the Communist organization within the populated areas.

(c) to isolate the bandits from their food and information supply organizations which are in the populated area.

(d) to destroy the bandits by forcing them to attack us on our own ground.

A master-stroke of power and simplicity, the Briggs Plan meant briefly that from now on security forces would protect the unpopulated areas, cut the enemy lines of communication between CTs and villagers, and force the CTs out to battle. Briggs planned to give the populated areas the confidence which only protection could bring, to implement Gurney's squatter plans, and by resettling half a million people, isolate the CTs from their food supplies.

It was a gigantic task, and it might well have failed had not Briggs and Thompson singled out the one factor which would prevent military escalation, the Briggs Plan confirmed that the authority for running the war must rest squarely on the shoulders of the civil government and the police. The troops were there to help. With one stroke Briggs allayed the fears of both the police and the civilian administrators that a new general might not realise that this was a war of intelligence, of CT defectors leading the police to others; a war demanding patience, in which a military patrol blundering into the jungle could in a day ruin months of painstaking work.'

Despite providing a framework to victory, the power Briggs needed was not at his hand. He remained until November 1951, went to London to 'debrief' the posting, before Sir Gerald Templer took over the posting and his mantle. Briggs was elevated to K.B.E. for his efforts and taking retirement for the second time, died at Limassol on 27 October 1952.

He was surely one of the finest Divisional Commanders to serve the British or Indian Armies; sold together with a number of original photographs and a copy of The Life and Campaigns of Lieutenant-General Sir Harold Rawdon Briggs by Tom Donovan.

Subject to 20% VAT on Buyer’s Premium. For more information please view Terms and Conditions for Buyers.

Estimate

£28,000 to £32,000

Starting price

£26000