Auction: 24002 - Orders, Decorations and Medals

Lot: 176

(x) A Great War D.S.C. group of three awarded to Lieutenant F. C. Smith, Royal Air Force, late Royal Naval Air Service, who flew as an Observer as part of the crews that attacked the Breslau and Goeben on 20-21 January 1918

Distinguished Service Cross, G.V.R. (Lieut F. C. Smith. R.A.F. January 1918.), hallmarks for 1917; British War and Victory Medals (Lieut. F. C. Smith), nearly extremely fine (3)

D.S.C. London Gazette 14 September 1918:

'Acted as observer for Flt. Cdr. Sorley during a determined and successful bombing attack on the "Breslau" on the 20th January, 1918, and also during subsequent day and night attacks on the "Goeben".'

One of ten such awards for this action.

Frederick Charles Smith was born on 26 April 1896, the son of Charles and Kate Smith. He was educated at Sir William Borlase's School, Marlow and listed his address 3 Boscombe Road, Shepherd’s Bush. Joining the R.N.A.S. at Eastchurch he was posted to the 2nd Aegean Group where he joined the raid on the Goeben and Breslau.

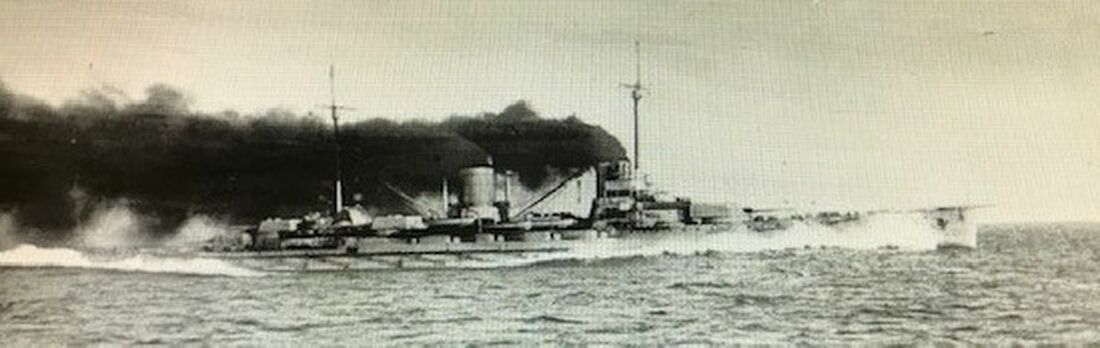

The Sortie of Goeben and Breslau

The Goeben and the Breslau, with four destroyers in attendance, got under way at 4.00 p.m. on 19 January, and at half-past three on the morning of the 20th they were at the Nagara net. At twenty minutes to six they were at the entrance to the Straits off Sedd el Bahr, and a quarter of an hour later, when they were on the outer edge of the channel reported clear by the German sweepers, they turned to the south-west. The new course was to carry the Germans between the two lines marked in pencil on the captured chart. Actually it took them on to the southern end of the complex of fields to the westward of the entrance; and at ten minutes past six the Goeben struck a mine.

The damage done to the Goeben was not serious, so the German Admiral did not allow the accident to deter him, and held on. It was a misty morning, and he seems to have been fairly certain that he had not yet been reported; this was indeed the case, for the look-out on Mavro Island had seen nothing. Soon after the mine exploded, the two German ships turned north; the Breslau was sent ahead to prevent any ships that might be in Kusu Bay from escaping. The destroyers had already turned back. In this order, the German ships passed Kephalo lighthouse at a distance of about two miles. The mist was still thick, and though the officers in the German ships seem to have sighted the lighthouse, the look-out men did not see them and it was not until a few minutes later that the enemy were sighted by the ships off Kusu Bay. The two drifters on the nets, the officers in the Raglan, the look out situation, and the commanding officer of the destroyer Lizard, which was patrolling northeast of the bay, all sighted the enemy more or less simultaneously; the code word "Goblo" was made by the Lizard and repeated by the Raglan. The word signified that the enemy were out. It was sent to commanding officers of ships and squadrons, who had always understood that the signal would be preceded by definite warnings. Before any action could be taken, indeed, before Admiral Hayes-Sadler could issue any orders, the Goeben opened fire upon the look-out station at Kephalo and some sunken ships in the bay (&.40). Simultaneously or nearly so the Breslau brought the Lizard under a well-directed fire, and drove her northwards. After that the German light cruiser opened upon the Raglan. The enemy's shooting was accurate and rapid; the Raglan's gunners answered with the six-inch gun and from the turret, but before they could get in range the German shells had found their target. The foretop and the director-top were hit in rapid succession, and all the control gear was at once put out of action. The engine-room was struck by two more salvoes, all the lights went out and the telephone communications were cut and destroyed, nor did the other monitor-M28- fare any better. The commanding officer held his fire for a brief interval, and by the time he opened upon the enemy they had his range. By now both the Goeben and the Breslau were firing upon the monitors and in a few minutes they were helpless. The drifter skippers endeavoured to cover the doomed ships with a smoke screen, but the enemy's fire was far too heavy for them to get into position.

Meanwhile Lieutenant-Commander J. B. Newill in the destroyer Tigress, which was patrolling to the westward of the Lizard, intercepted his colleague's signal and steamed off rapidly to join him. When he rounded the point he saw the Raglan had already sunk, and that the small monitor was blazing. The Lizard was again closing Kusu to render assistance. Soon after he had taken stock of the position, Lieutenant-Commander Newill came under fire from the Breslau (8.20), which was to the southeast of him and steering south. He was then steering southwards and hugging the land fairly closely. The Breslau's salvoes fell close, but none hit his ship, and he continued to dog the enemy until he was near Cape Kephalo. He then steered north for a short distance and was soon afterwards joined by the Lizard (8.40). By now the alarm was general. Admiral Hayes-Sadler at Salonica received the first news of the raid just before eight o'clock; Captain P. W. Dumas at Mudros took in the signal at about the same time, and ordered steam to be raised in the Agamemnon, the Lowestoft, the Skirmisher and the Foresight. Throughout the Aegean the commanding officers of the detached squadrons gave the necessary orders for bringing the convoys into port, and for sending out their available forces to the patrol stations allotted them in Admiral Fremantle's orders.

When the German Admiral saw that the two monitors were destroyed and that the look-out station at Kephalo was badly damaged, he determined to execute the second and more hazardous part of his programme: the bombardment of Mudros and the ships inside the harbour. It was with that object that he was directing his course when Lieutenant-Commander Newill and his colleague in the Lizard had come together and begun to follow him. A sudden disaster turned the Germans from their plan. They had intended to keep strictly to the track which had carried them clear of the minefields since the early morning; but the detonation in the Goeben had put the compasses out of action. The navigator was now fixing the successive positions of the ship by simultaneous sextant angles of prominent objects. In ordinary circumstances this is a difficult and hazardous method of steering, and the German ships evidently got some way to the eastward of their intended track. Their new course took them well into the minefields between Sedd el Bahr and Cape Kephalo, and at half-past eight the Breslau struck a mine. At the moment she was passing ahead of Goben; she did not at once come to a standstill, but continued to move forward along the minefield.

The look-out men reported that they were in the middle of a large field; the mines were visible all round in the clear, blue water. The Goeben was carefully manoeuvred to take the Breslau in tow, but before the towing hawser could be passed she also struck a mine (8.55). A few minutes later, Lieutenant Commander Newill in the Tigress and Lieutenant N. A. G. Ohlenschlager in the Lizard, who were now approaching, saw a succession of explosions round the Breslau. She detonated four more mines and began to settle down fast. Admiral von Rebeur-Paschwitz realised that his flagship was in grave danger; the damage done by the last mine was serious, the Goeben was being attacked vigorously by aeroplanes and was a fine target for any British submarine that might be about as she lay motionless in the minefield. He now gave up all thought of bombarding Mudros and decided that the Breslau must be abandoned. His navigator extricated the ship from the surrounding mines with great skill and a few minutes after the Breslau sank, the Goeben was being steered to the southwest so that she might be taken round the minefields by the route followed on the way out. As the Goeben made off for the entrance to the Straits, the destroyers that had been left behind early in the morning came out to rescue the survivors of the Breslau. Lieutenant Commander Newill and his colleague pressed on to engage them, and at about 9.30 shots were exchanged. The enemy destroyers did not join action, but retired, and after a short unsatisfactory stern chase the Tigress and the Lizard came under fire from the shore batteries, and so close to the shallow minefields that further pursuit was impossible. Meanwhile the Goeben had turned eastwards towards the Straits. Her new course took her into the fields for the third time during the day and she again struck a mine as she crossed them at 9.48 a.m.. She now listed over to port; but in spite of her injuries was still able to steam at a fair speed.

Whilst the Goeben was making her way back into the Straits our forces at Mudros were leaving harbour. They were too late to intervene and Admiral Hayes-Sadler, who was making preparations against a protracted raid lasting for many days, ordered Captain Dumas to meet him off Cape Paliuri at the southeastern entrance to the Gulf of Salonica. By now our air forces were hovering over the crippled Goeben and reporting her movements. As she approached Nagara Point two planes were observing her closely; the officers in them saw her turn suddenly and unaccountably towards the land and run fast aground. The German captain had made a mistake about the positions of the buoys marking the passage through the net, and had given a wrong order to the helmsman. It was now about 11.30 a.m.

The news that the Goeben was aground was received at the air headquarters in Imbros and Mudros soon after the aeroplanes had seen the accident, from then onwards the German battle cruiser was bombed without respite. These attacks, though executed with the utmost daring and pertinacity, did practically no damage; but they made the salvage work extremely difficult.

Admiral Hayes-Sadler steamed into Mudros at 1.45 p.m. on the 21st, some time before he reached his anchorage he knew that the Goeben had retired. The Admiralty had also received the news and wired to the Commander-in-Chief telling him that every effort should be made to destroy the Goeben, and instructing him to go in person to the Aegean. He reached Mudros in the Lowestoft on the 25th. The Goeben was stil ground, the attacks from the air were being continued with the greatest vigour but an attempt to bombard her by indirect fire from a monitor had not been successful. Submarine attack was the only possible means of damaging her beyond repair.

There was only one submarine off the Dardanelles at the time, and one of her propeller shafts was out of action. E14 (Lieutenant Commander G. S. White) was therefore ordered into the Aegean from Corfu, and on the night of the 27th she sailed for the Straits. The obstructions off Chanak were far more formidable than they had been in the early days of the Dardanelles campaign, when British submarine commanders entered the sea of Marmora almost at will; but Lieutenant Commander White passed them, although with great difficulty. When he reached the position where Goeben had been aground he found that she had gone. The German battle cruiser had been worked free and towed off two days before. Lieutenant Commander White turned back. On his way to the net he sighted a Turkish auxiliary and fired a torpedo at her, this seems to have warned the Turks that a submarine was in the Straits and to have put them on their guard, for E14 was attacked almost immediately by a depth charge which did considerable damage. From now onwards the British submarine was very difficult to handle and when Lieutenant Commander White was at last compelled to bring his boat to the surface, the Turkish batteries at once opened up on her and she sank in deep water. Lieutenant Commander White was killed by the bursting shells and his body, terribly mangled, rolled into the sea just before his submarine went down.

As soon as the raid was over, the Commander-in-Chief urged that the minefields at the entrance to the Straits should be reinforced; the Admiralty agreed, and the necessary orders were issued. But, although no one on our side could know it, there was no chance that the Goeben would break out again. Her damages were far too great to be repaired in the dockyard at Constantinople, all that the Germans could do was to build coffer-dams and improvise bulkheads round the rents in the battle cruiser's hull and keep her in harbour. Apart from this, the raid caused great excitement in Constantinople. When Admiral von Rebeur-Paschwitz first laid his plans before the Turkish authorities, Enver Pasha had warned him to be careful and to remember that the Goeben and Breslau were as valuable to Turkey as the Grand Fleet to Great Britain. As soon as it was known that the Breslau was lost and the Goeben in grave danger, the Turks were bitterly indignant. It seemed to them that the German naval staff had been reckless with the national property entrusted to them, for the Goeben and Breslau had sailed under the Turkish flag and had long since been regarded as part of the Ottoman navy. Enver and his colleagues were quite determined that the Goeben should never again be risked in what they regarded as a foolhardy enterprise. The German U-boats were, in fact, a far more serious menace, actual and potential, than the damaged Goeben. The repairs on Goeben repairs lasted from 7 August to 19 October.

Before the repair work was carried out, Goeben escorted the members of the Ottoman Armistice Commission to Odessa on 30 March 1918, after the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk was signed. After returning to Constantinople she sailed in May to Sevastopol where she had her hull cleaned and some leaks repaired. Yavuz and several destroyers sailed for Novorossiysk on 28 June to intern the remaining Soviet warships, but they had already been scuttled when the Turkish ships arrived. The destroyers remained but Goeben returned to Sevastopol. On 14 July the ship was laid up for the rest of the war. While in Sevastopol, dockyard workers scraped fouling from the ship's bottom. Goeben subsequently returned to Constantinople, where from 7 August to 19 October a concrete cofferdam was installed to repair one of the three areas damaged by mines.

The German navy formally transferred ownership of the vessel to the Turkish government on 2 November. According to the terms of the Treaty of Sèvres between the Ottoman Empire and the Western Allies, Yavuz as she became known was to have been handed over to the Royal Navy as war reparations, but this was not done due to the Turkish War of Independence, which broke out immediately after World War I ended, as Greece attempted to seize territory from the crumbling Ottoman Empire. After modern Turkey emerged from the war victorious, the Treaty of Sèvres was discarded and the Treaty of Lausanne was signed in its place in 1923. Under this treaty, the new Turkish republic retained possession of much of its fleet, including Yavuz.

Epilogue

Confirmed in his citation has having joined the Royal Air Force as a Lieutenant by 1918 he was posted to No. 220 Squadron on Imbros. Smith was flying with them in July 1918 when he died, Smith is buried at the Lancashire Landing Cemetery; sold together with copied service papers.

Note there are three men named Lieutenant Frederick Charles Smith flying with the R.A.F. in 1918 however only one has previous service with the R.N.A.S.

Subject to 5% tax on Hammer Price in addition to 20% VAT on Buyer’s Premium.

Sold for

£2,500

Starting price

£800