Auction: 24001 - Orders, Decorations and Medals

Lot: 98

(x) The outstanding campaign group of six awarded to Lieutenant A. L. Kennedy, Australian Imperial Forces, a pioneering Antarctic Explorer from the 'Heroic Age'

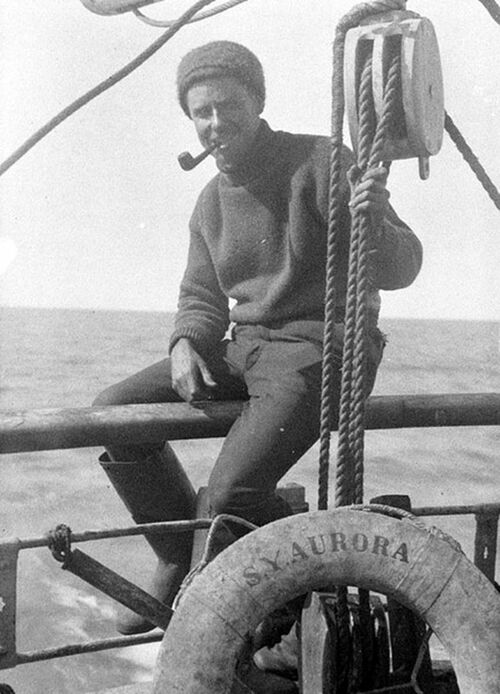

Kennedy was completing his studies at Adelaide University when being selected by Sir Douglas Mawson as Magnetician for his first Antarctic Expedition, being a key member of the Western Party, whilst further serving on Frank Wild's Eastern Journey; Kennedy answered the call of duty during the Great War, being wounded in action for good measure, before returning to the fold for a further Antarctic foray - once again under Mawson - for the BANZAR Expedition, in the course of which he earned the extremely rare combination of the Polar Medal in both silver and bronze

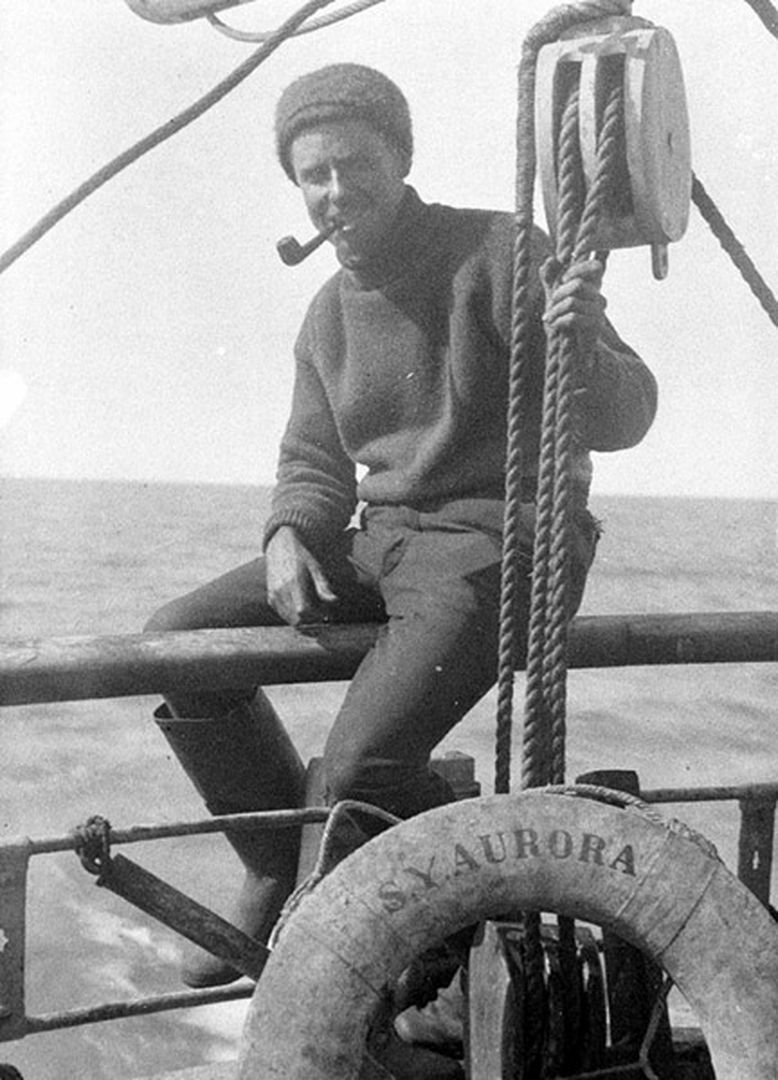

British War and Victory Medals (Lieut. A. L. Kennedy. A.I.F.); War and Australian Service Medals 1939-45 (S31419 A. L. Kennedy.); Polar Medal 1904, G.V.R., silver issue, 1 clasp, Antarctic 1912-14 (A. L. Kennedy, "Aurora"); Polar Medal 1904, G.V.R. crowned head, bronze issue, 1 clasp, Antarctic 1930-31 (Alexander L. Kennedy.), good very fine (6)

Provenance:

Spink (Nobles Australia), March 1992.

When it was introduced in 1904, the Polar Medal in silver was awarded to men who had wintered while the bronze Polar Medal was given to the officers and crew of the relief ships. The two Medals are separate awards and thus both may be worn. Only 18 men, including Alexander Kennedy, have been awarded both.

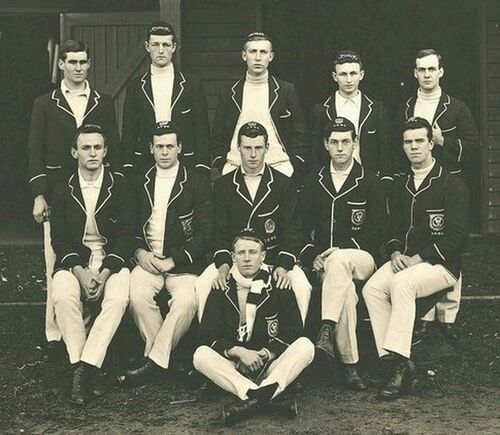

Alexander Lorimer Kennedy was born in Woodside, South Australia, on 23 April 1889. His father was the Headmaster of North Adelaide School, thus young Kennedy was educated by his father and then at St Peter's College and the University of Adelaide, from which he graduated in 1911. While at University he was a prominent member of the Boat Club, taking his Blue in 1908. He was the stroke of the University VIII - Cecil Madigan (another Australian Polar explorer) rowed at bow - that won the inter-University competition, besides being on the Intervarsity Rifle Shooting Team.

Antarctic - first foray

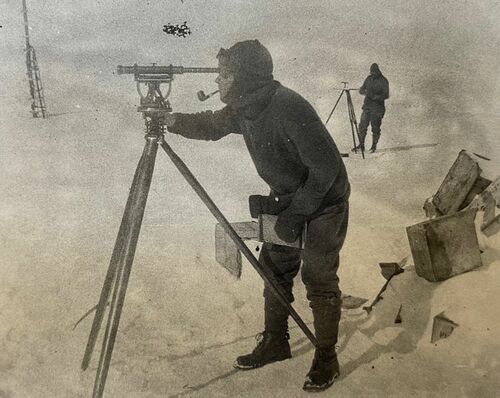

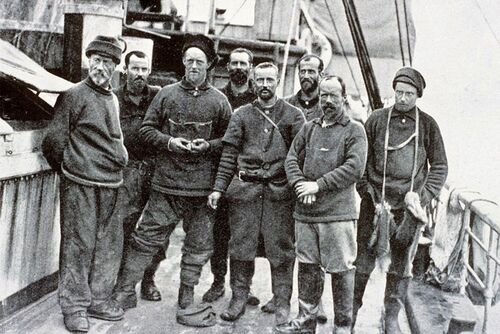

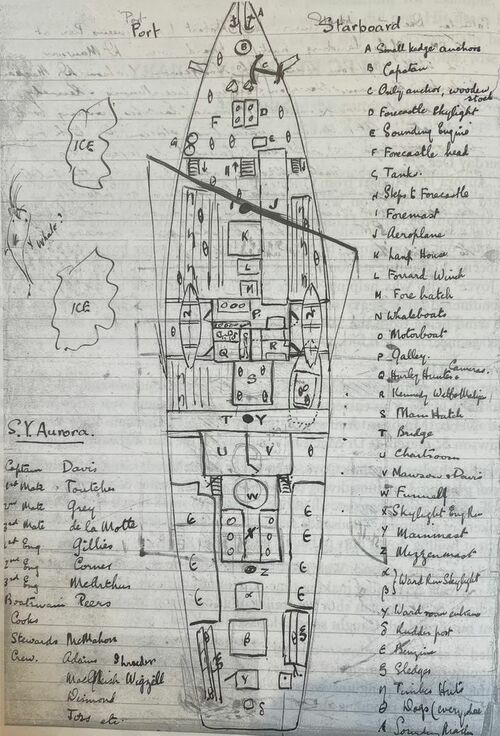

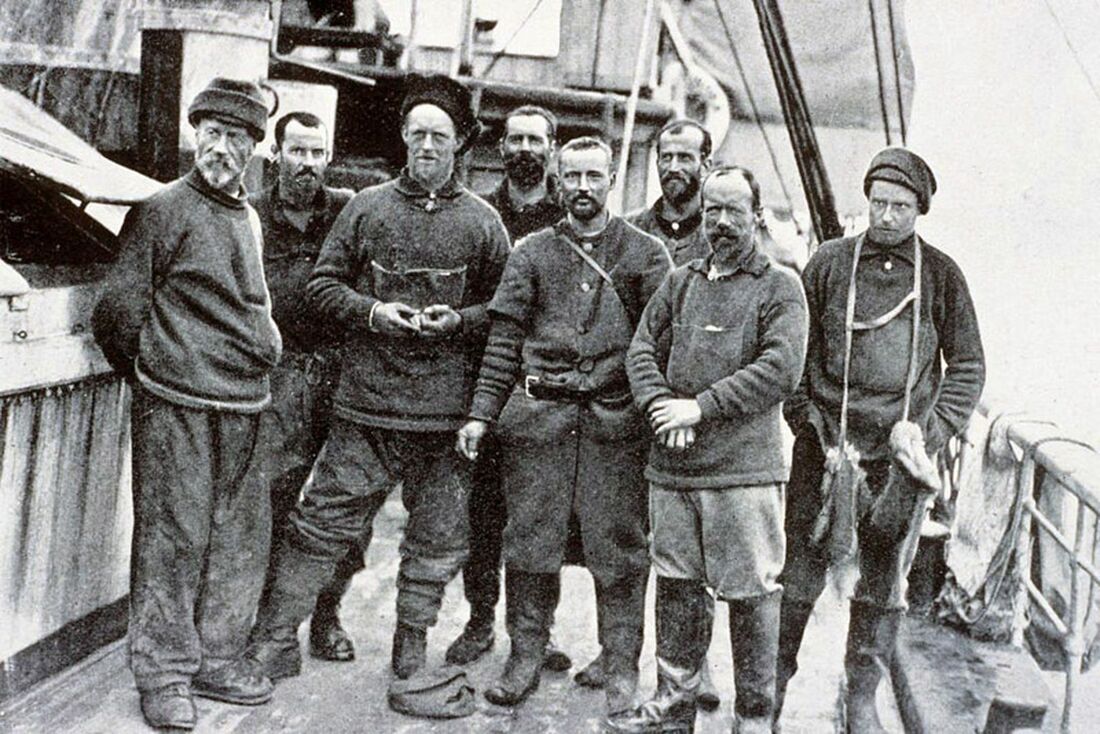

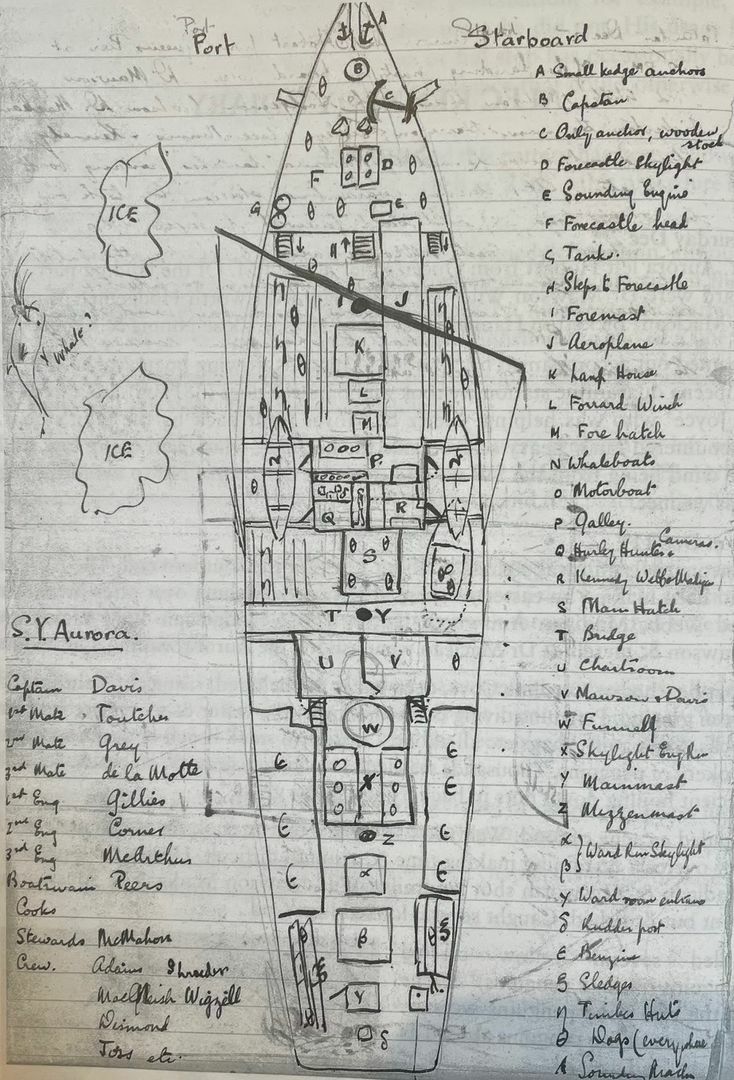

Later that year, Kennedy joined Mawson's Australasian Antarctic Expedition (AAE) as physicist and navigator with the Western Party led by Frank Wild, which spent a year on the Shackleton Ice Shelf. He had taken a number of magnetism classes whilst still at University in order to prepare for what was required of him on the expedition. Frank Wild was the leader of the eight-man Western Party, Sydney Jones, medical officer; Charles Hoadley and Andrew Watson, geologists; Morton Moyes, Meteorologist; George Dovers, Cartographer; Charles Harrisson, Biologist and Alexander Kennedy, Magnetician. The site of their base on the Shackleton Ice shelf was precarious and chosen in some desperation. Ever since the Aurora left Commonwealth Bay, Captain Davis had been looking for a suitable location for the Western Party. They had come west some 2,500km without finding a suitable landing place. It was then early February 1912 and, with only a few days' coal in reserve, Captain Davis was thinking of abandoning the search and heading for Hobart and home. However on 15 February they sighted a massive ice shelf that they named the Shackleton Ice Shelf, after Sir Ernest, whose birthday it was that day. Now, an ice shelf is not the best place to site an expedition hut as they have a tendency to break up and float away, but Frank Wild thought it would be safe enough, and far better than an ignominious return to Hobart. Over the next few days, the crew of the Aurora deposited 40 tons of stores and equipment, including 12 tons of coal, onto the ice shelf.

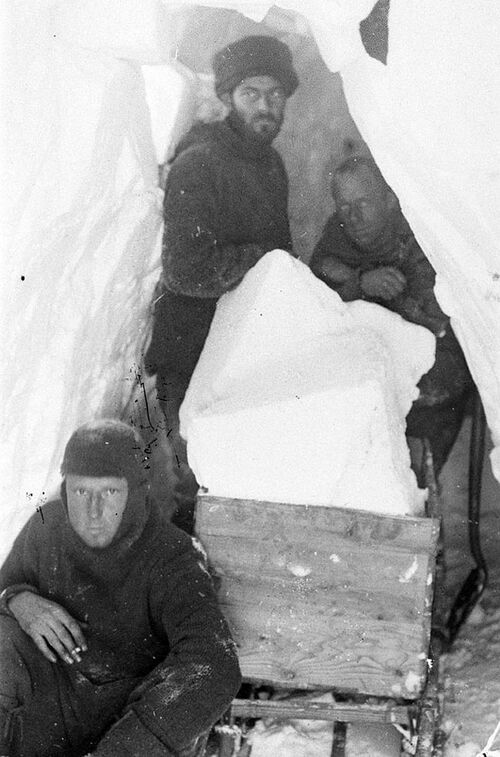

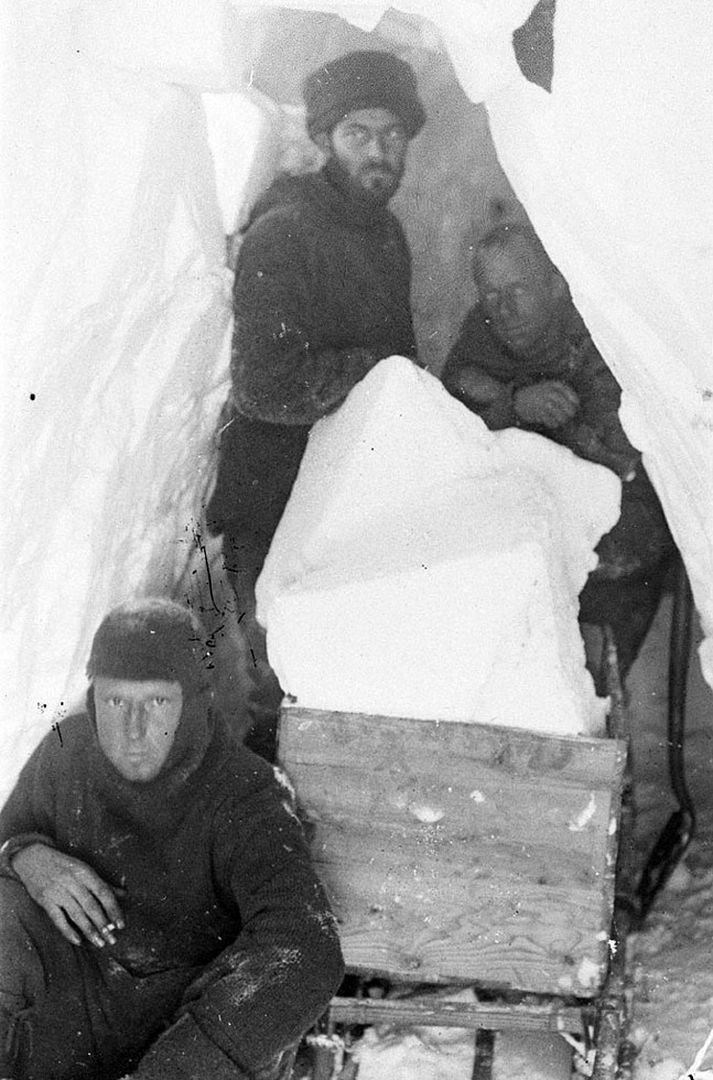

Wild thus selected a spot some 585m inland from the ice cliffs for the location of the hut and work began immediately on its construction. The hut was designed for eight men. It was 20 feet (6.1 m) square, with a 6 foot (1.8 m) wide veranda around three sides, and entry was through a vestibule with an outer and inner door to keep the weather out. Unfortunately, the bolts that were designed to hold the prefabricated sections together had been left behind in Australia and they had to make do with nails. Any concerns they may have had about the stability of such construction were unfounded. Within a very short time the whole structure was engulfed in snow up to the eaves as the building became part of the ice shelf. They dug blind tunnels and passageways into the accumulated snow to use as store rooms and tunnels and named the finished warren of a habitation 'The Grottoes'. Frank Wild, the only man with any polar experience, decided to take the men man-hauling and teach them how to work the sledges, cross crevasses and generally cope with the environment. This was a familiarisation exercise, albeit a harsh introduction to what would be expected of them next spring. The nine Greenland dogs they had brought with them would not be fit to haul sledges for some months and took no part in these early training exercises.

The Western Party was the happiest of the three AAE bases, without the personality clashes of Macquarie Island or Mawson's unfounded expectation that all the men at Cape Denison shared his driving passion and enthusiasm. This was due to Frank Wild's laid back, consensus style of leadership. During the winter, they got up late, worked on their individual projects from 1000hrs until 1300hrs - there was not much for a biologist and two geologists to do on an ice shelf during winter! Only the meteorologist, Moyes, was kept busy taking regular readings through the day and night. During their copious free time they all took on additional tasks, with the exception of Moyes who was excused because of his meteorological duties. Hoadley acted as the storekeeper; Jones and Kennedy serviced the acetylene plant; Harrisson took care of the hurricane lamps; Watson looked after the dogs; and Dovers was the 'odd job man' who covered for whoever was on cook or night watch. Every Saturday they had a scrub-out to tidy up the base and of course there was a traditional church service on Sundays. During the winter they prepared the food and equipment for next spring's sledging season, including hand-sewing several hundred calico bags in which to store food and other items - the sewing machine the base had been supplied with came without needles and spools. They also sewed their own sledging harnesses under Wild's careful tutelage and made harnesses for the dogs. For entertainment they played cards - bridge was very popular - chess and draughts. Outside they devised a sort of 12-hole golf course around the hut. Played with hockey sticks and with many of the greens located in crevasses, a round of 'gokey' often proved an unexpectedly hilarious activity when the crusty ground beneath their collapsed or the ball suddenly disappeared down a crevasse.

The winter was not without its mishaps: Jones was slightly burnt when the acetylene generator he was filling burst into flame, Kennedy dislocated his knee whilst skiing, and Harrisson and Watson were very lucky when a cornice broke off and crashed down narrowly missing them.

During the winter, adverse weather in the form of recurrent blizzards kept them holed up in 'The Grottoes' for days at a time, however, unlike the Main Party at Cape Denison they experienced a number of fine, bright days that enabled them to get out and about laying-in depots for use the following summer.

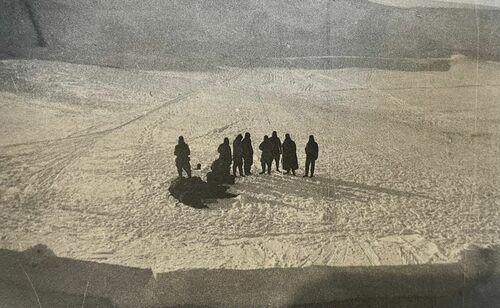

Wild planned two major sledging trips that summer. He would explore and chart the eastern coast of Queen Mary Land with Kennedy and Watson, collecting geological samples and making magnetic observations; while Jones, Dovers and Hoadley would explore out into Kaiser Wilhelm II Land as far as Gaussberg, which had been mapped by Drygalski in 1902. This left Harrisson and Moyes behind to continue the scientific observations at the winter quarters. However, Harrisson was keen to observe the snow petrels at the Hippo Nunatak, and Wild was persuaded to let him accompany the eastern sledging party. Harrisson was then to return to the winter quarters with the spare sledge and dogs.

Unfortunately, when they arrived at the Hippo Nunatak the depot they had previously stashed there had been destroyed and there was no sign of the sledge. Wild did not want to go on with only one sledge so the plan was changed and Harrisson remained with the sledging party. Back at the hut, this caused Moyes serious concern. He was expecting Harrisson's imminent return and, naturally thinking an accident had befallen him on the way back, set out to look for him, venturing as far as Henderson Island.

Wild, Kennedy, Watson and Harrisson continued in an easterly direction until they met impassable conditions associated with the Denman Glacier. With their way ahead blocked, Wild turned inland and went high up on to the ice cap before giving up and returning to 'The Grottoes'. In their nine weeks away, Wild and his party sledged more than 300 miles (a fraction under 500km).

Meanwhile, Jones, Dovers and Hoadley were still away exploring the coast to the west. They skirted round to the south of the Helen Glacier and spent five days at Haswell Island on account of a snow storm but in between times managed to explore the immense emperor penguin rookery nearby (about 7,500 birds) and collect all sorts of biological and geological specimens from this island. They spent Christmas at Gaussberg, where they found two cairns and numerous bamboo poles left by the German Antarctic Expedition ten years earlier. They were then 215 miles (346km) from 'The Grottoes'. On Boxing Day they turned for home. The unexplored terrain ahead of them appeared, as far as the eye could see from the summit of Gaussberg, similar to the terrain they had already traversed with very few prominent features by which to navigate.

Whereas the outward journey had taken seven weeks, they made their way back to 'The Grottoes' in half the time. Soon thereafter, the sea-ice started breaking out and although they did not know it, the Aurora would be with them in a little over a month. They went out to the edge of the sea-ice hunting. Seals were taken both for food and as biological specimens. Harrisson made a number of fish-traps which he lowered through the ice to rest on the bottom. On retrieval the traps yielded a mixed bag of fishes, amphipods and an octopus. The Aurora hove into view on 23 February 1913 and the men of the Western Pary were soon onboard and on their way home.

Great War - Somme

On his return to Australia, Kennedy established and operated a magnetic observatory in Western Australia for the Carnegie Institution, Washington, D.C. With the outbreak of the Great War, he joined the Australian Imperial Force and served in France as an officer in the 2nd Australian Tunnelling Corps and was wounded on 1 July 1916, the First Day of the Battle of the Somme. Returned home by 1919, from 1921 he worked at Adelaide Observatory for four years, followed by two years at the newly built Mount Stromolo Observatory in Australian Capital Territory.

Antarctic - Second Innings

Kennedy latterly served as Physicist on the second voyage of Sir Douglas Mawson's BANZAR Expedition. Set up to claim a large slice of Antarctica Kennedy joined Captain Scott's old vessel, the noble Discovery, on 19 November 1930 at Hobart. Three days later she set sail for Cape Denison, the site of the main base on Mawson's Australian AAE in 1912-14, via Macquarie Island. The Discovery then proceeded westwards and charting the coast of Adélie Land and spotting from the Gipsy Moth seaplane Banzare Land and Sabrina Land in January 1931 and Princess Elizabeth Land and MacRobertson Land spotted from the air the following month. With coal reserves running low, the Discovery returned to Hobart. In 1936 some 40% of the Antarctic continent from 45°E to 160 °E with the exception of the French Adélie Land was claimed as the Australian Antarctic Territory.

During the Second World War Kennedy served with the Australian Motor Vehicle section, until discharged in October 1942. A mining engineer throughout his life, Kennedy retired in the 1960s and died at Perth, Westen Australia in August 1972.

Two locations in the Antarctic, these being Cape Kennedy, a cape on the eastern side of Melba Peninsula, Queen Mary Land and Mount Kennedy, a peak, 2km south of Mount Rivett in MacRobertson Land, are named in his honour.

Sold together with his pressed card identity tags for both the Great War and the Second World War (4) and a copy of his Antarctic Diaries, covering the Australasian Antarctic Expedition, besides copied research.

Subject to 5% tax on Hammer Price in addition to 20% VAT on Buyer’s Premium.

Sold for

£17,000

Starting price

£7000