Auction: 24001 - Orders, Decorations and Medals

Lot: 50

Sold by Order of the Recipient

'If my photographs evoke memories then my job has been done. I’m proud to be counted as a member of the Class of '82 and have the tattoo to prove it.’ - Haley reflects.

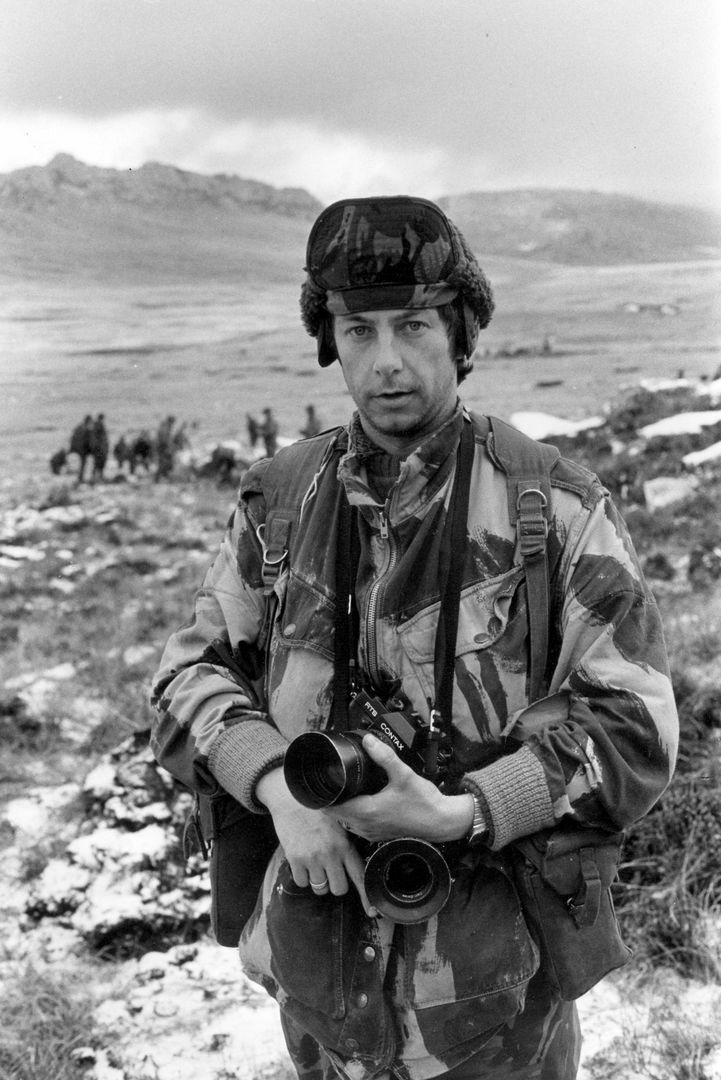

The well-documented South Atlantic Medal awarded to P. R. G. Haley, Senior Photographer for Soldier magazine during the Falklands War; he was attached to 5th Infantry Brigade throughout the conflict and served with the 2nd Battalion, Scots Guards during the Battle of Mount Tumbledown, before capturing the iconic photograph of 7 Platoon, 'G' Company at the point of victory on 14 June 1982 - it remains as perhaps the most famous image of the entire conflict

South Atlantic 1982, with rosette (P R G Haley Photographer Soldier Magazine), mounted as worn, minor official correction to magazine name, good very fine, in its named box of issue (Lot)

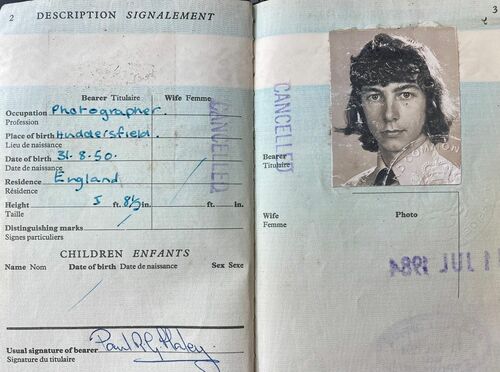

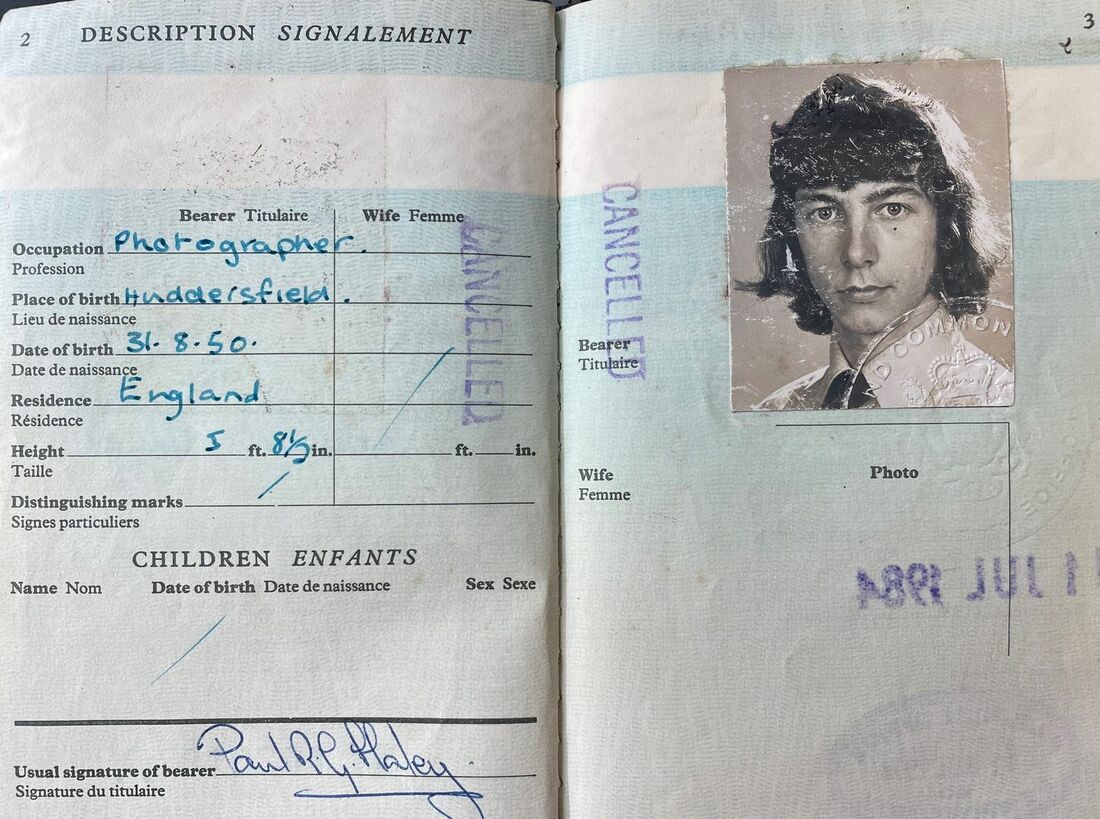

Paul Richard Graham Haley was born at Huddersfield on 31 August 1950, the only son of Harry and Joyce. Young Haley went to Colne Valley High School in Linthwaite and left school at 15, whilst having a weekend job of being a wedding photographer. This would lead him to take up an apprenticeship with a local portrait studio. Having learned the ropes, by 1971 he had applied to join the Ministry of Defence and was firstly posted to the Royal Artillery at Larkhill. Three years later an advert caught his eye stating:

'...must be prepared to travel anywhere in the world at 24hrs notice.'

This was the post of Senior Photographer for Soldier magazine and unsurprisingly there were over 100 applicants for such an opportunity. Such was the scope of his work in the previous years that despite his tender age, Haley was given the posting, becoming the youngest photographer to be given this senior job.

Learning the ropes

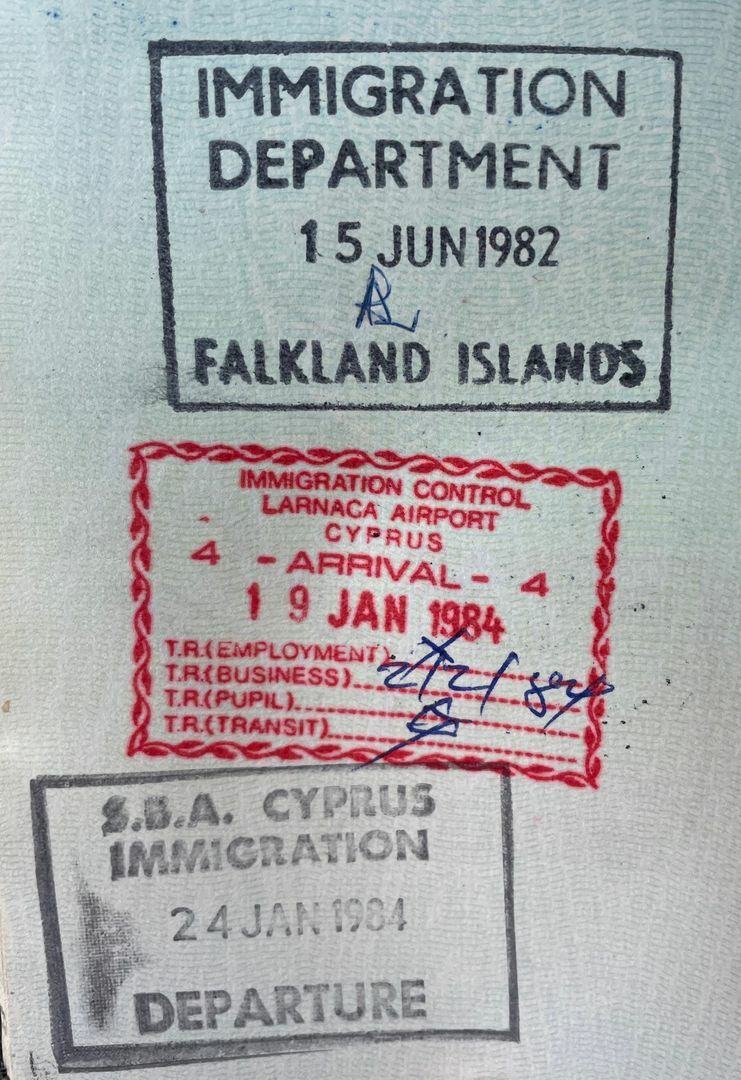

As his Passport confirms, the opportunities at Soldier saw Haley earn his fair share of air miles. From 1974-82, he went off to various countries to document the military involvements in Germany (numerous), Cyprus, Hong Kong, Gibraltar, Kenya and Malaysia.

Falklands - opening 'shots'

With the invasion of the Falkland Islands by Argentine forces on 2 April 1982, the British Task Force was swiftly raised. It is no surprise that this conflict would be a new frontier for the media in telling the story of war. However, at this point the MOD were not interested to have reporters and photographers too close to events. The team at Soldier was soon on the case, trying to convince the powers that be to give them an opportunity. They were firstly permitted to capture images of various units training and packing for the conflict at home, before seeing them off to port. Haley was tasked with travelling with 5 Brigade to Southampton and seeing them off on the Queen Elizabeth 2, capturing images of the units being loaded and the transformation of their transport. Having developed the images and passed them onwards, a call came through that would certainly change his life. It was that Brigadier Sir Mathew John Anthony Wilson, 6th Bt., had personally requested he join the Task Force. Haley had met the Brigadier in Wales several weeks prior during a training exercise. He was down at Southampton at 1030hrs the following morning and came aboard in time for her departure. He gives more detail:

'....I was allocated a room. It was a double cabin above the waterline with sea view (Cabin 2094). Very nice and possibly the best way to go to war. The sea view didn't last for long as we had to black out all the windows with bin liners and black army tape soon after leaving Freetown.'

Having left port, opportunities for unusual and unique scenes to be captured on film were plenty when you consider that it was a luxury cruise liner that was to take a military Task Force on campaign. He was under the watch of Lieutenant-Colonel Dunn, onboard with the MOD PR Department and someone he had worked closely with before. Haley was also afforded all the benefits of the Officers on board, giving access to all areas of the ship. He went and made himself known to the Skipper, Captain Jackson who have him freedom on the Bridge. It was from there he watched them leave Southampton, although '...the feeling of the ship's foghorn sounded loosened my fillings almost.'

Things got underway, the soldiers on board kept fit, training continued apace and all knew the pressure was starting to rise. The first casevac also required a Sea King to land and take off the patient. Haley swiftly bagged up some spent rolls of film and addressed them to Soldier HQ. He entrusted the bag to a nurse who accompanied evacuation and in several weeks the images he had taken found their way into the National Newspapers and television channels across the world.

Knowing they would be stopping at Ascension Island, Haley took his fears of being 'thrown off' once things got serious to the Brigadier. The reply he got was that he considered Haley just a member of the Brigade as anyone else afloat and that he would land with them if he so wished. Haley continues:

'...‘I was a press photographer – of course I wanted to! Every one of my photographer friends would have jumped at the chance. I certainly wasn’t going to turn it down. I cross decked to Canberra in Gritviken, South Georgia then landed at San Carlos.’

His call sign was to be 'Sunray, SolMag' and Haley managed to source some kit for the time ashore, boots from a Rapier Corporal, wet weather gear from an injured Gurkha, besides webbing, water bottle and sleeping bag from the QM Stores, who '...felt sorry for me'.

Haley then found himself attached to as many forward units as he possibly could during the conflict. His first night was spent in a shelter with the Gurkhas, as the helicopter he had flown in had come into contact whilst they tried to push forward to Darwin or Goose Green. In the coming days he managed to catch up with the Brigadier in Darwin, capturing the famous 'Darwin pig' on film, it insisted on using an unexploded bomb as a scratching post and was denied its use when the Royal Engineers Bomb Disposal Team came into town. Haley went onto Goose Green in the first days of June 1982 and walked the steps that the gallant men of 2 Para had done a couple of days before, carefully recording all that he saw. It was a moving scene, with '...the Gorse bushes still burning and the remains of Battle very evident.'

In those days, Haley was busy from dawn till dusk, capturing important images of battlefield burials, wreckages and similar scenes. Moving forward to Fitzroy on 7 June and then Bluff Cove, he came under the Skyhawk attack, which could not be stopped by the Scots Guards. The enemy aircraft then went to the east and turned to attack the Sir Galahad and Sir Tristam. Black smoke rose as evidence of the costly hits which had been made.

Battle of Mount Tumbledown

As the charge for Stanley continued, Haley ensured he was close to the units which would share in the actions soon to follow. He went up onto Goat Ridge with the 2nd Battalion, Scots Guards. They were preparing to take Mount Tumbledown by force. Haley recalls:

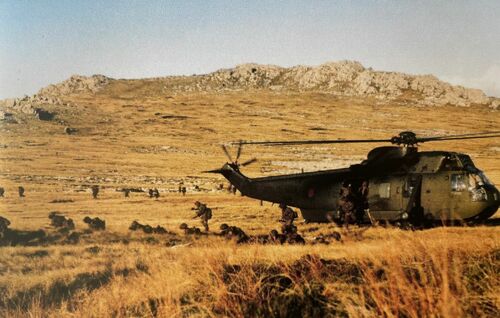

'...I went forward in a Sea King and started to dig in with the rest of the troops. We came under sporadic shell fire and one man was injured when a shell exploded setting off a phosphorous grenade attached to his webbing which he'd taken off while digging his trench. I'd often thought on exercises that each man carrying his own spade was a bit of a waste of time and that one between two should have been ample. It's only when under shell fire that you realise you wish you had your own rather than waiting for someone to finish using theirs.'

He managed to get a helicopter ride back to Fearless, as Canberra was not in the bay. Dropping off film and gathering supplies, early the next morning Haley '...blagged another helicopter ride back to Goat Ridge with a Section of SAS guys.'

That afternoon, Lieutenant-Colonel Scott briefed his Company Commanders with their orders for the attack. Tumbledown was to be taken, the men to keep moving at all times and take no shelter no matter what came at them, for if they stopped it would be all but impossible to get moving again. He recalls what he saw:

'That night I watched from the top of the hill from the start line for the Battle for Tumbledown and they did just that. Walking forward through a hail of gunfire and shells with parachute flares lighting the way.

I saw for a while with Angus Smith the Chaplain of the Scots Guards. We were in a trench which was gradually filling with ice cold water. There was sporadic shelling from the Argentine guns around Stanley. The crump sound of the explosion appearing to come after the bright, almost firework-ish, flash of the exploding shell and shrapnel, some of which dug itself into the peat between us. "I think we should pray" said Angus as I dug the still burning hot metal out. I told him I didn't believe but for him to go ahead by himself if he felt he needed to. He said that my own faith must be very strong as most people in that situation would have prayed whether they believed or not, just to hedge their bets. He was a nice man.'

The Scots Guards further gilded their laurels for their actions on 13-14 June 1982. Lance Corporal Rennie gives his own account:

'Our assault was initiated by a Guardsman killing a sniper, which was followed by a volley of 66mm anti-tank rounds. We ran forward in extended line, machine-gunners and riflemen firing from the hip to keep the enemy heads down, enabling us to cover the open ground in the shortest possible time. Halfway across the open ground, 2 Platoon went to ground to give covering fire support, enabling us to gain a foothold on the enemy position. From then on we fought from crag to crag, rock to rock, taking out pockets of enemy and lone riflemen, all of whom resisted fiercely.'

Major Kiszely, who was to become a senior general after the war, was the first man into the enemy position, personally shooting two enemy conscripts and bayoneting a third, his bayonet breaking in two. Seeing their company commander among the Argentinians inspired 14 and 15 Platoons to make the final dash across open ground to get within bayoneting distance of the marines. Kiszely and six other Guardsmen suddenly found themselves standing on top of the mountain, looking down on Stanley under street lighting and with vehicles moving along the roads.

The 2nd Battalion, Scots Guards lost eight dead and 43 wounded during the Battle for Mount Tumbledown and in consequence of gallantry shown that day its men were rewarded with one DSO, two MC's (including one to Major Kiszely), two DCM's (including one posthumous, sold in these rooms) and two MM's.

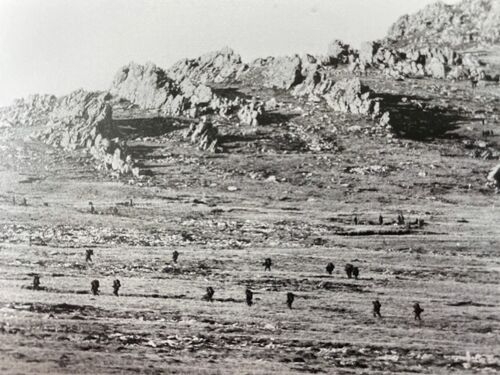

Haley was to capture perhaps the most famous photograph of the whole conflict shortly after 1122hrs on 14 June. He was with the men of 7 Platoon, 'G' Company when the radio of Guardsman MacAskill confirmed the Battle had been won. They were nearing the peak of Tumbledown and snow was starting to set in. Gathering the Guardsmen together and bringing his camera to focus, he perfectly captured the moment of victory. That image still resonates today and as soon as it had been taken, a snowstorm closed in.

Jumping into a Wessex helicopter, Haley was focussed on getting towards Stanley as soon as possible. It was clear to all that 14 June 1982 would be the final day of the conflict. Dropped off to join some Marines, Haley then found himself having been placed into a minefield. The Marines were awaiting some Engineers to clear the field, whilst he could see the Moody Brook and the road headed to Stanley. Rather than await clearance, Haley took the decision to trace the footsteps of the Marines in and then take to the road himself. Thankfully it passed without issue!

He flagged down a lift in a Snowcat, which sped towards Stanley and caught up with the men of 3 Para. Commandeering bunks in some bungalows west of the Stanley War Memorial, he dropped his gear and headed for the town itself. At that moment he caught something that had remained under embargo until 2011. It was a helicopter, with Colonel Mike Ross and Captain Rod Bell of 22 SAS, draping a white flag underneath it. Haley caught the helicopter going into Stanley to negotiate the surrender. Despite submitting the negative in 1982, the image was never published in the public domain.

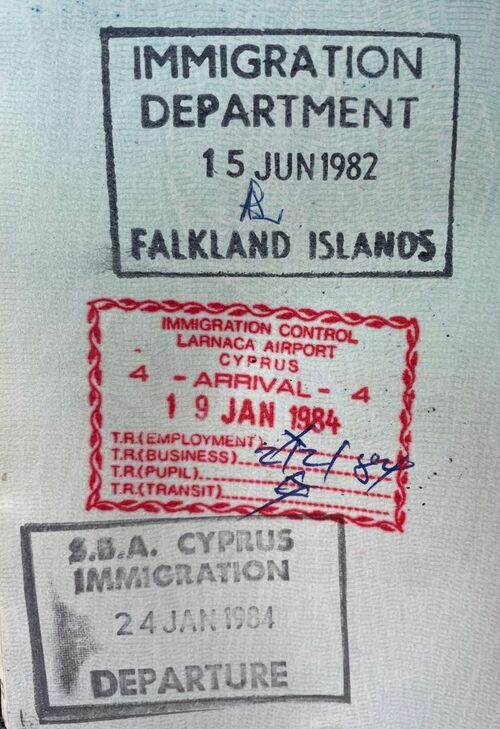

Once the surrender came, there were further duties for Haley to record scenes of surrender and the state in which war had left the Falkland Islands. The sheer amount of materiel which had found its way there was staggering. So what the job in returning all the Argentine prisoners home. Time had also come to get a stamp in his Passport, dated 15 June 1982, from the Falkland Islands Immigration Department to formally acknowledge his arrival. The press in the Falklands had several ways to try and get home. Many of the vessels were sailing long routes home and places were limited on the Hercules aircraft which needed to take 22 SAS home. Lots were drawn for the spots and Haley came out on the third lift that left. He went out with three other journalists and sixteen men of the Special Air Service. They made it home to Brize Norton with no attention drawn to their arrival.

Haley returned to work the next day with quite a lot to catch up with. He had taken over 2,000 images during the conflict. His Editor requested his process the films he had with him, prepare captions and then perhaps take 3 days leave. Disputes followed with the Civil Service Pay Department who requested that he produce receipts for the accommodation whilst he was overseas. Eventually £1.20 per night was agreed for a 'hard lying allowance' - it made no special arrangement for the digging of his slit trench or the shells which came in his direction. Haley went up to the Depot of the Parachute Regiment to receive his Medal and Rosette. Whilst sharing a beer after the presentation in the Sergeants Mess, a chirpy Para piped up '...all you need now is a chest to pin it on.'

Haley remained with the MOD for a further five years, making further visits to Belize, Beirut, Canada, Norway and The Gambia. He opened his own studio in Yorkshire in 1987 and took up freelance work. Since the conflict, he has twice returned to the Falkland Islands.

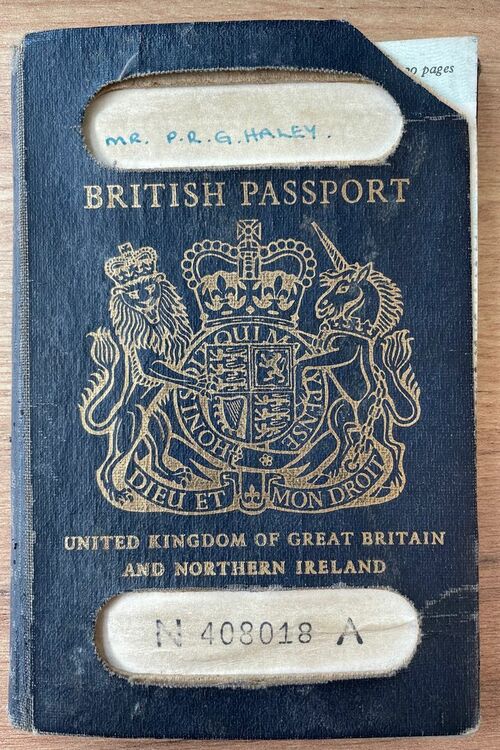

Sold together with the following original archive comprising:

(i)

His Passport, covering the period 1974-84.

(ii)

An Argentine bayonet and bullet from the conflict, together with two stones from Mount Tumbledown.

(iii)

A signed copy of One Man's War.

(iv)

Approximately 200 original hand printed images from the conflict, each 250mm x 200mm, together with a large folder with twenty-eight larger-format mounted and signed photographs, these an important archive.

(v)

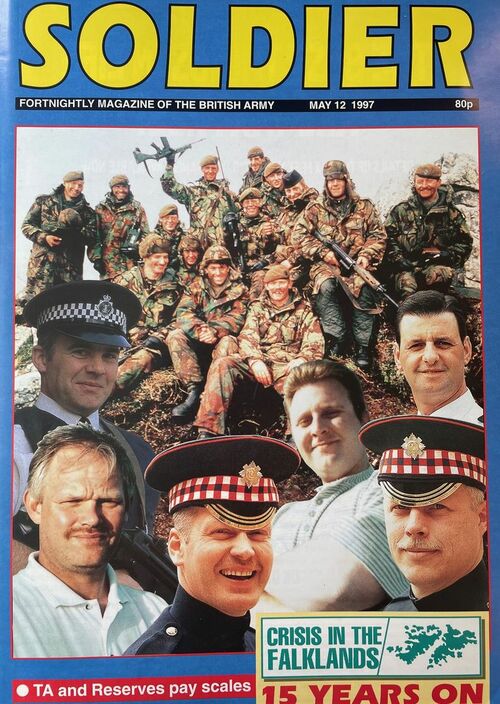

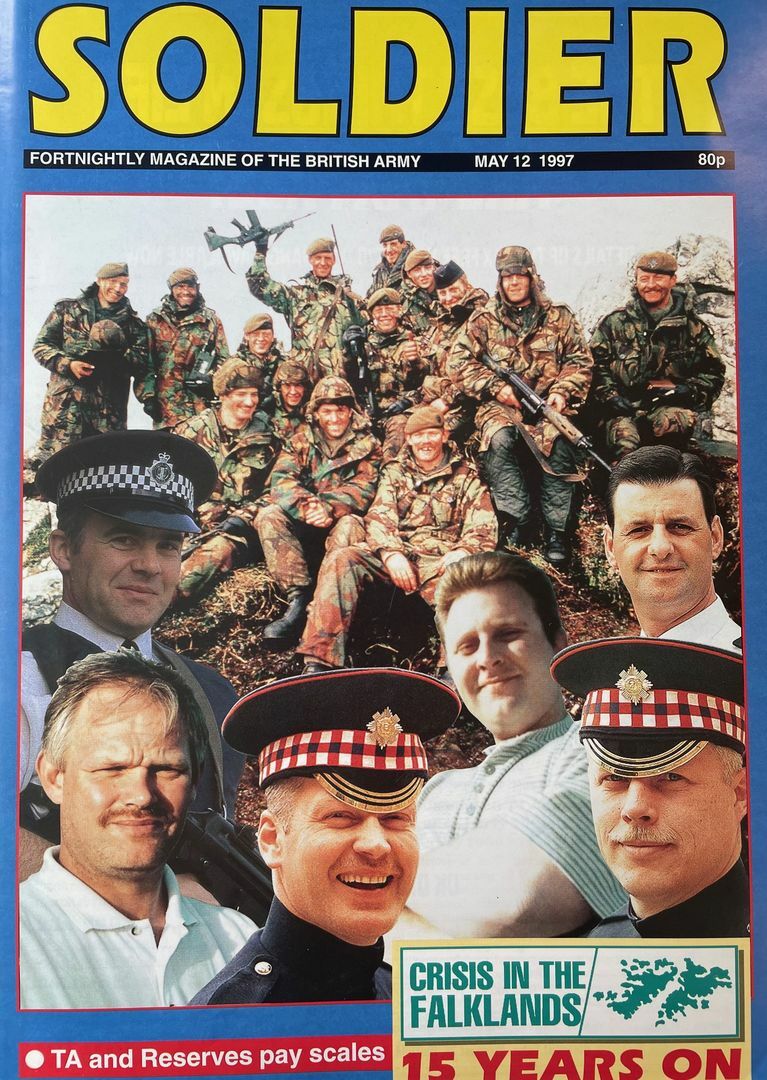

Copy of Soldier, 12 May 1997, featuring a report on the men who were photographed in the famous 'Tumbledown Victory' image.

In 2024, the Imperial War Museum published War Photographers, with an image of Haley on the front cover. He also published One Man's War in 2011:

www.blurb.com/bookshare/app/index.html?bookId=5673217

Haley was also recently interviewed on his career:

soundcloud.com/jonathan_kempster/radio-walks-podcast-interview-with-paul-haley

www.youtube.com/watch?v=4VD0562_6ko

A good biographical entry, together with several quotes have been sourced from the Falklands35 Blog:

https://falklands35blog.wordpress.com/2020/11/22/falklands-35-paul-r-g-haley/

Subject to 20% VAT on Buyer’s Premium. For more information please view Terms and Conditions for Buyers.

Sold for

£6,500

Starting price

£1800