Auction: 23112 - Orders, Decorations and Medals - e-Auction

Lot: 498

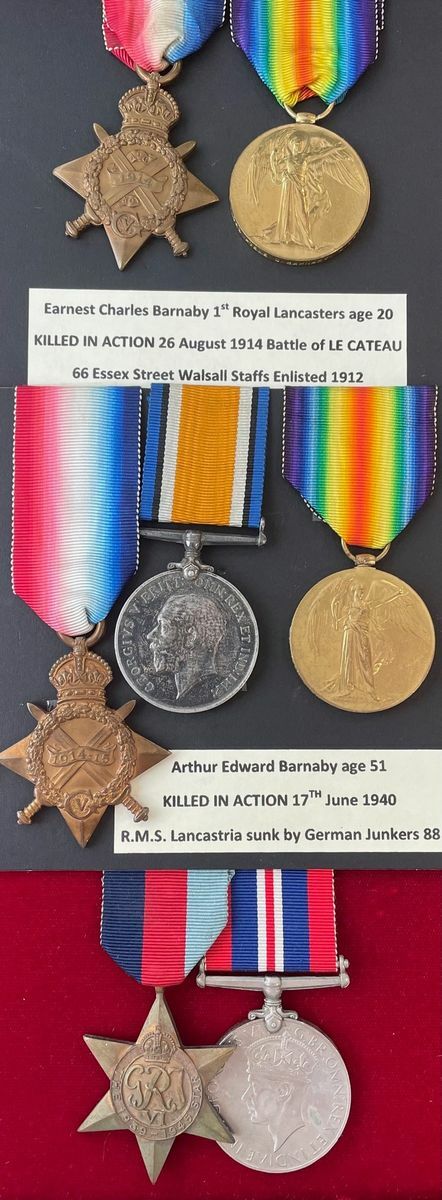

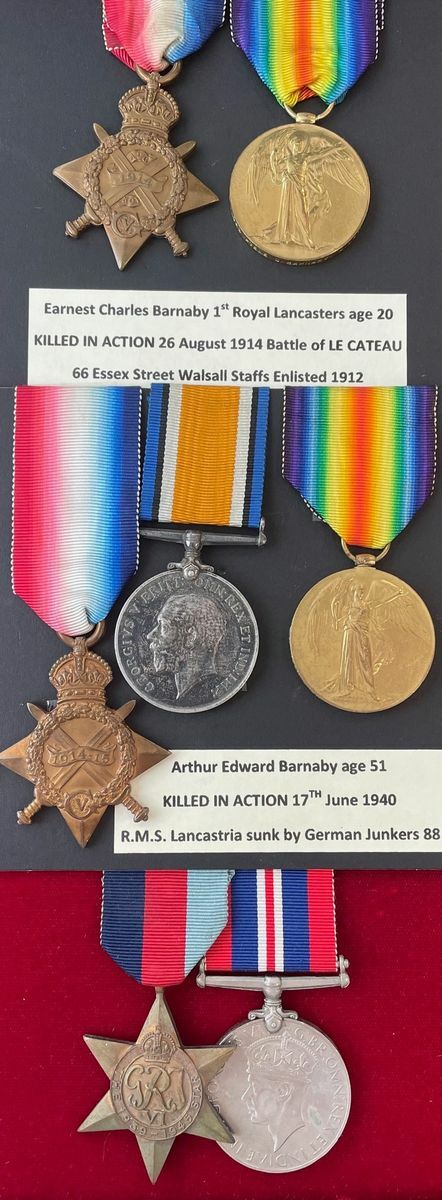

Family group:

Pair: Private E. C. Barnaby, 1st Battalion, The King's Own (Royal Lancaster Regiment) who was killed in action on the 26 August 1914 at the Battle of Le Cateau, when the Regiment suffered some 400 casualties in a single two-minute burst by German machine gunners

1914 Star (10743 Pte. E. C. Barnaby. R. Lanc: R.); Victory Medal 1914-19 (10743 Pte. E. C. Barnaby. R. Lanc. R.), very fine

Five: The poignant group of five awarded to Private A. E. Barnaby, Pioneer Corps, late 2nd Battalion, The King's Own (Royal Lancaster Regiment); re-enlisting in 1939 he was killed when the Lancastria was bombed and sunk off St. Nazaire on 17 June 1940

1914-15 Star (10650 Pte. A. Barnaby. R. Lanc: R.); British War and Victory Medals (10650 A-Cpl. A. Barnaby. R. Lanc. R.); 1939-45 Star; War Medal 1939-45, very fine (7)

Ernest Charles Barnaby was born on 8 July 1894 at Walsall, West Midlands and was a railway goods porter by trade. Barnaby and the 1st Battalion were mobilised on 4 August 1914 at Dover, arriving in France on 23 August 1914 after sailing on the Saturnai.

Following the retreat from Mons the Battalion found themselves on the Ligny Road at dawn on 26 August 1914. An account of the catastrophic following three hours is described by Captain G.R.R. Beaumont who was in B Company at the time:

'We arrived at dawn by the Ligny Road to a spot where subsequently we suffered so heavily. The Battalion was ordered to form close Column facing the enemy's direction of defences. Companies were dressed by the right, piled arms, and place equipment at their feet. There was a big stir because some of the arms were out of alignment and the equipment did not in all cases show a true line. A full 7 to 10 minutes was spent in adjusting these errors. The Brigade Commander rode up to the Commanding Officer and shortly afterwards we were told to remain where we were as breakfast would shortly be up. Everyone was very tired and hungry having had nothing to eat since dinner the day before. A remark was passed as regards our safety. My Company Commander replied that French Cavalry were out in front and the enemy could not possibly worry us for at least three hours.

Three Companies of the Battalion in close Column, the fourth company just about to move up to the left with a view to continuing a line with the 20th who had just commenced to dig in. Just about this time some Cavalry (about a troop) rode within 500 yards of us, looked at us and trotted off again. I saw their uniform quite distinctly and mentioned that they were not Frenchmen. I was told not to talk nonsense and reminded that I was very young. It was early in the morning and nobody felt talkative, least of all my Company Commander? The Cavalry appeared again in the distance and brought up wheeled vehicles; this was all done very peaceably and exposed to full view. We could now hear the road transport on the cobbled road and a shout went up "Here's the Cooker". New life came to the men and Mess Tins were hurriedly sought. Then came the fire. The field we were in was a cornfield. The corn had been cut. Bullets were mostly about 4 feet high just hitting the top of the corn stalks. Temporary panic ensued. Some tried to reach the valley behind, others chewed the cud; of those who got up most were hit. The machine gun fire only lasted about two minutes and caused about 400 casualties. The 4th Company moving off to the left was caught in columns of fours. Shell fire now started and did considerable damage to the transport, the cooker being the first vehicle to go. A little Sealyham terrier* that we had collected at Horsham St. Faith's before embarking, and that the troops had jacketed with the Union Jack was killed whilst standing next to the Driver of a General Service Wagon. I mention this as I saw the same Driver the day after still carrying the dog, he was very upset when he was ordered to bury it.

The Commanding Officer was killed by the first burst and the Second in Command rallied the Battalion; several of us taking up position to the right of the point where we had suffered so heavily.

An attack was organised at once, we re-took our arms and got in most of the wounded. The others were left and taken prisoner later at Haucourt Church that night.'

The above extract from a letter of an officer of the King's Own. As regards the last sentence of it, 4 Division (it should be remembered) had no Field Ambulance and it therefore had great difficulty in getting any of its wounded away. It was also deficient of signals, Cavalry, Cyclists, Royal Engineers Train and Divisional Ammunition Column.

The 4th Division Headquarters at Haucourt got the 'overs' from this firing, the General's ADC and several men being hit. Stragglers began to come back into the village where the Divisional Staff collected them and led them forward again to the position North of Warnelle Ravine.'

Barnaby is commemorated on the La Ferte-Sous-Jouarre Memorial.

Arthur Edward Barnaby, a native of Walsall, West Midlands, was born on 1 May 1882 and was an enameller by trade. Mobilised with the 2nd Battalion he left for India when war was declared. The Battalion was then sent to France arriving on 16 January 1915; the Walsall Advertiser reports that Barnaby was wounded in early 1915.

The Battalion took part in some of the most ferocious fighting of early 1915, including the bayonet charge at Zwartelen on 17 February 1915, repulsing an attack near Ypres on 21 February 1915. They were to witness the German gas attack on Allied troops at Gravenstafel on 24 April 1915. On 8 May 1915 the Germans attacked the Frezenberg Ridge as part of the 2nd battle of Ypres, The Battalion had been 1100 strong at the beginning but by the end of the day could only muster sixty-seven men. The final casualties for the day were recorded as 15 officers and 893 men.

Leaving for Egypt in November1915 the Battalion spent the remainder of the war in Salonika taking part in the battle at Doiran.

By 1939 Barnaby was a labourer, when he re-enlisted for the Second World War. He was posted to 50 Company, Auxiliary Military Pioneer Corps as part of the British Expeditionary Force in France at the age of 50. Having been taken off he was killed in action when the Lancastria was bombed and sunk off St. Nazaire on 17 June 1940.

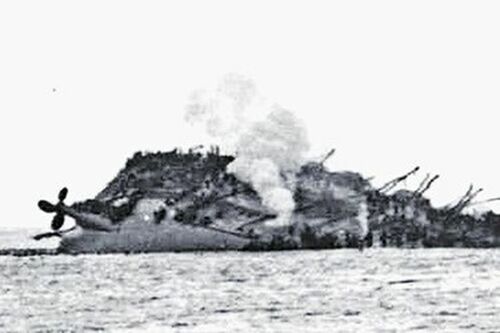

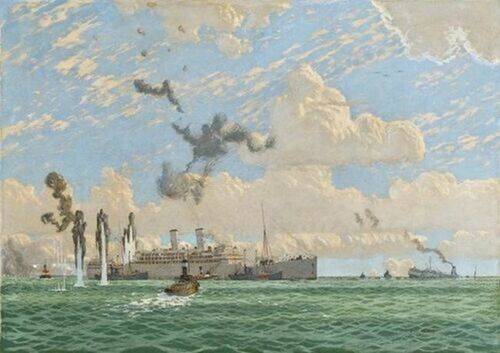

Loss of the Lancastria

Much has been written about the disaster that occurred off St. Nazaire on 17 June 1940, but by way of summary, the following extract is taken from Charles Hocking's Dictionary of Disasters at Sea:

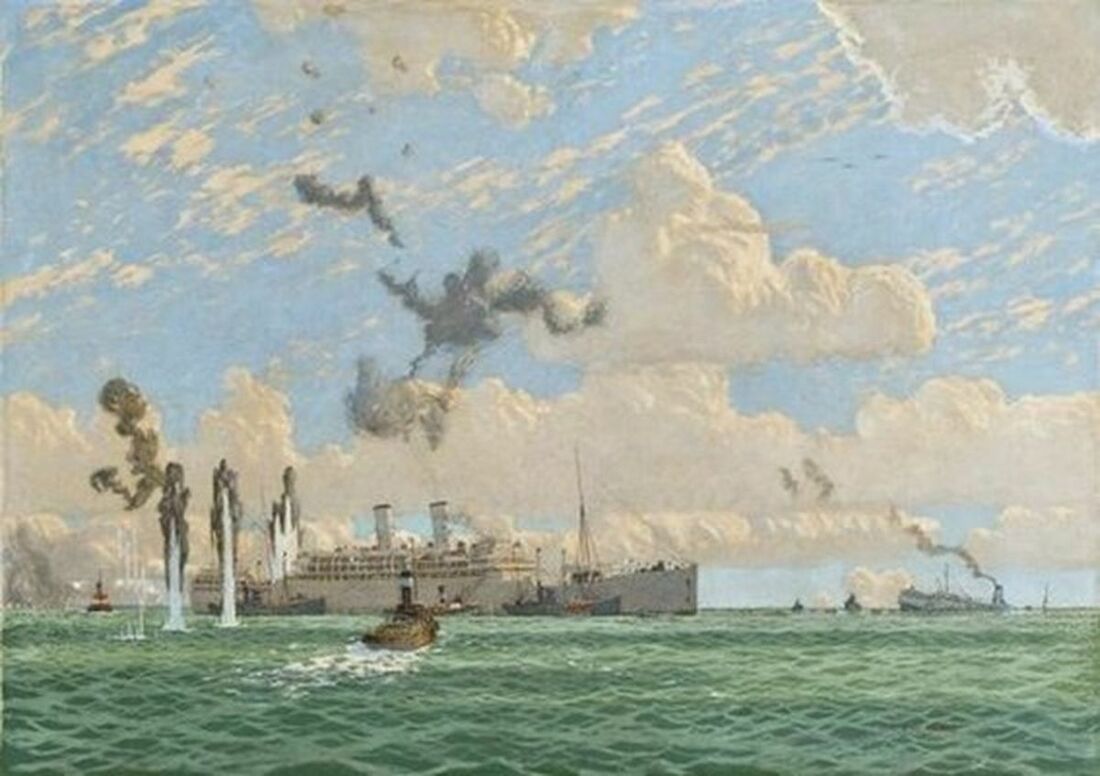

'On 17 June 1940, the Cunard White Star Line's S.S. Lancastria, Captain J. Sharp, was lying off St. Nazaire takin on board British troops who were being evacuated from France. The embarkation began at 8 a.m. and continued until 4 p.m., by which time the liner was ready to weigh anchor. In addition to the soldiers there was a small party of civilians, and their wives and children. As far as can be ascertained there were 5,310 persons on board, of whom 300 were crew.

The first attack by aircraft came about 2 p.m., followed after a short interval by a second raid. In these attacks the Orient liner Oronsay was hit and damaged but still remained seaworthy.

At about 4.30 p.m., in a third attack, the ship was struck by a salvo of bombs, one of which passed right through the dining saloon and burst in the engine room. The damage to the Lancastria was vital and she took a heavy list, and although the boats were got out with all possible speed it was evident from the outset that there was no hope of rescue for thousands of those on board. Only two lifeboats managed to get away, the others capsizing owing to difficulties with the falls or through being overloaded. Tugs and other small craft were quickly on the scene and picked up hundreds of men in the water.

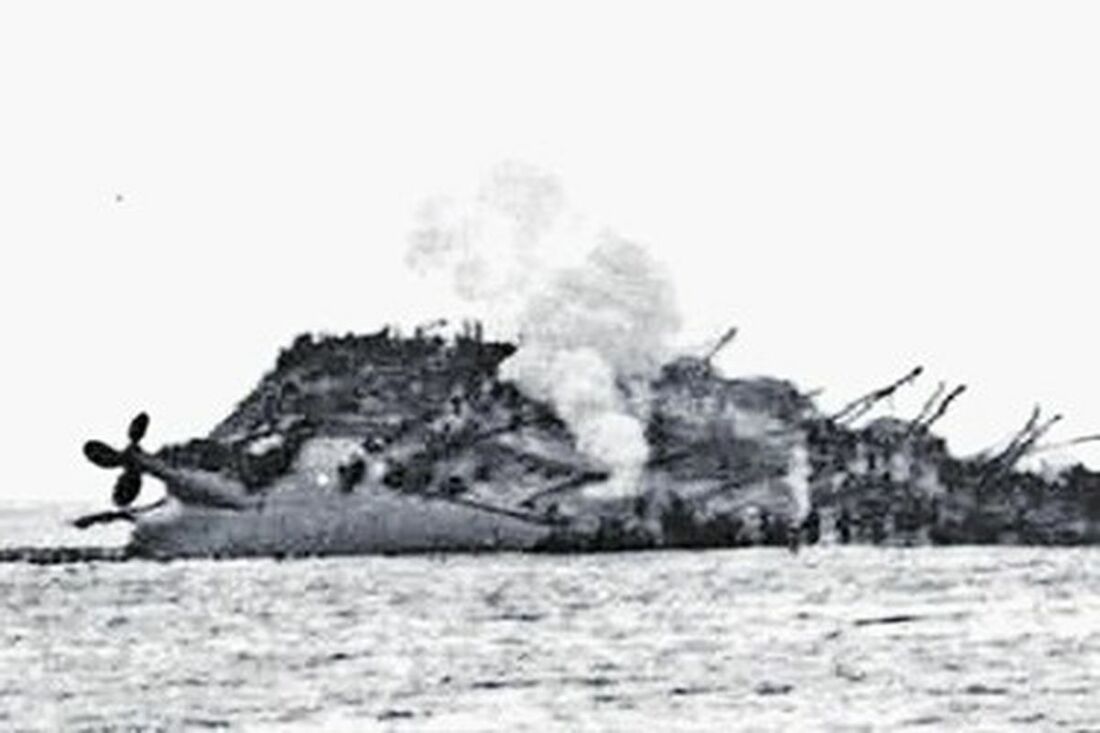

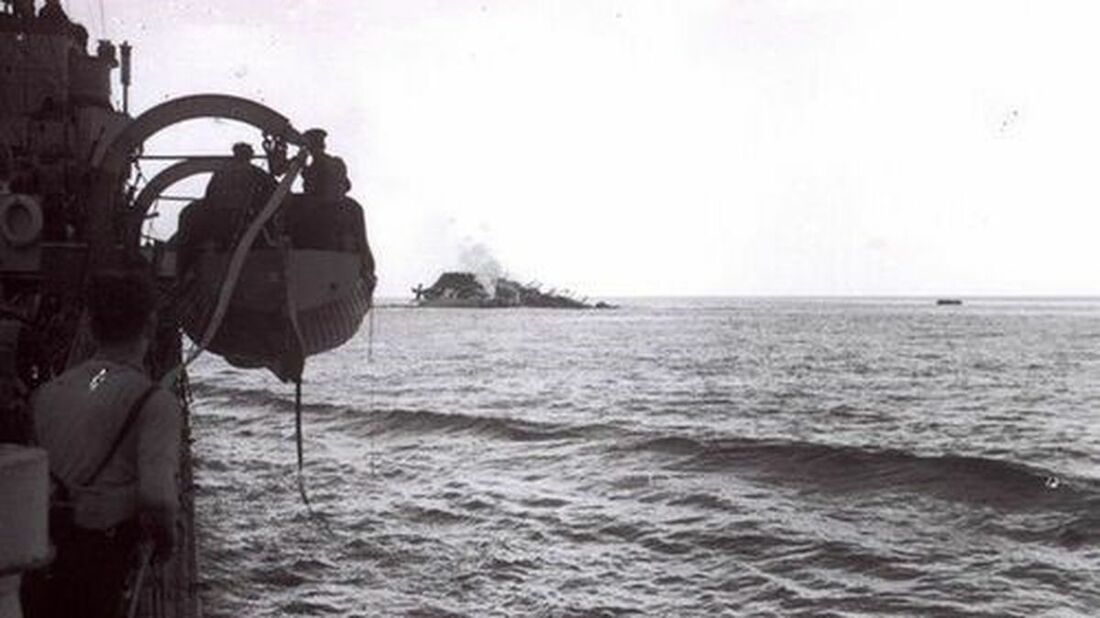

The Lancastria remained afloat for barely 30 minutes, turning gradually over to port so that those still on board were able to walk upon her side as she lay. After floating in this position for some time she capsized completely and went down by the head.

Meanwhile the German airmen occupied themselves by firing from their machine-guns at the men in the water, and by firing incendiary bullets which set fire to the oil floating on the surface.

Of those on board 2,477 were saved, including Captain Sharp, who was picked up some hours later, and most of the civilian passengers. There was also a small number of people who came ashore singly or in very small parties, some of whom were captured and interned by the Germans.'

Barnaby did not survive and now rests in the Pornic War Cemetery.

The Barnaby family thus lost a son to both World Wars.

Subject to 20% VAT on Buyer’s Premium. For more information please view Terms and Conditions for Buyers.

Sold for

£350

Starting price

£170