Auction: 23003 - Orders, Decorations and Medals

Lot: 316

(x) Sold by Order of a Direct Descendant

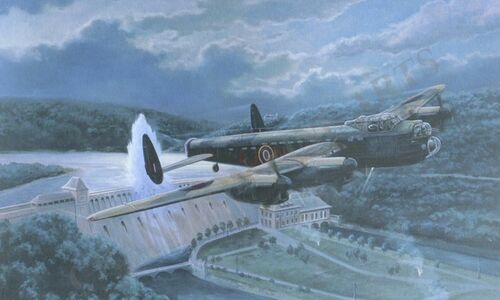

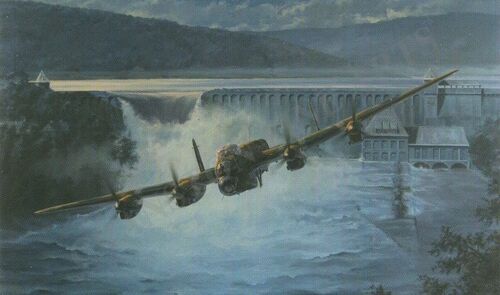

'Then we were instructed to bomb and I think we made perhaps three trial runs before we made our final attack. Les Knight was very good and got us down quickly to a low level, and we had a good run-in. I could clearly see the towers and I was quite happy with my bomb-sight and position – and I released the bomb...

I didn’t actually see the Dam burst because I was out of sight, being in the front of the aircraft – but it was obvious what had happened by the noise on the intercom from the rear gunner, and everybody else who could see anything was going mad on the intercom, because the centre had fallen out of the dam and the water was absolutely pouring down this narrow river, causing a veritable tidal wave, and we forgot all about safety and going home and we were trying to follow the water down the river to see what happened. It was a terrifying sight. We could see cars being engulfed, then Gibson called up and said, ‘Well, it’s all right boys, you’re having a good time – but we’ve still got to get back to base. Let’s go.’

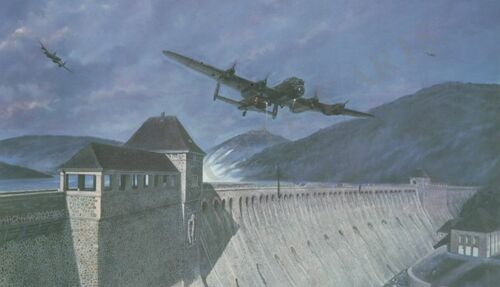

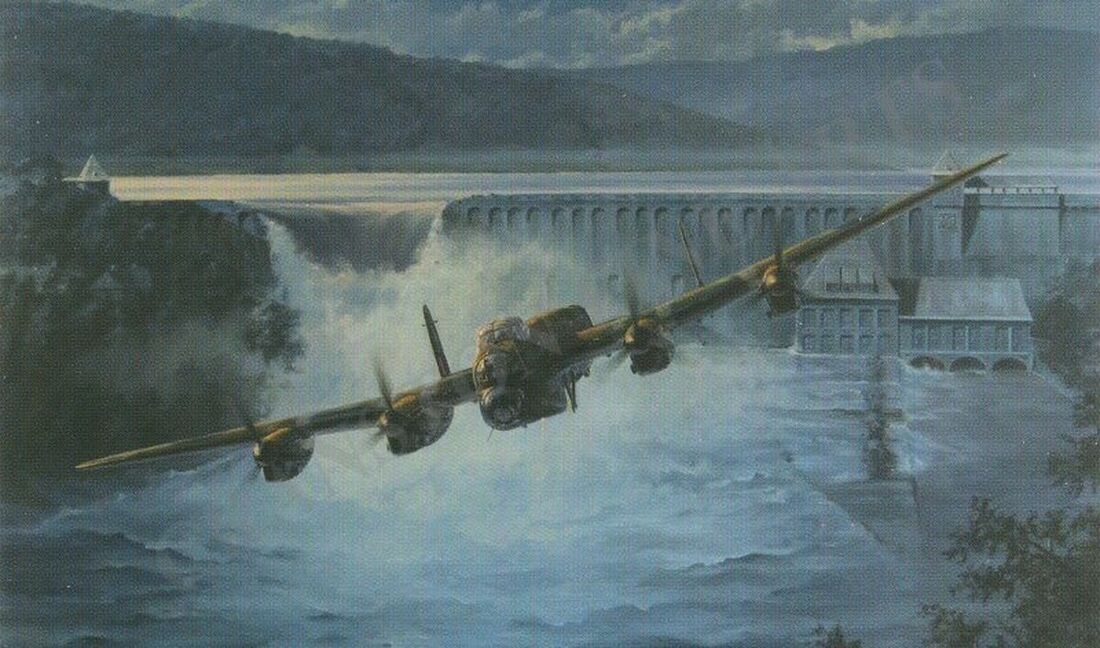

Johnson recalls the famous 'bouncing bomb' he delivered perfectly to breach the Eder Dam

The historically important immediate 1943 'Operation Chastise' D.F.C. group of five awarded to Flight Lieutenant E. C. 'Johnnie' Johnson, No. 617 Squadron, Royal Air Force

Having begun his career with a full Tour in No. 50 Squadron in the crew of Sergeant (later Flight Lieutenant) L. G. 'Les' Knight, Royal Australian Air Force, Johnson soon established himself as a Bomb Aimer of considerable skill, being marked out as a member of an 'Ace Crew' and gaining early appointment as Squadron Bombing Leader; the outstanding ability of the crew was recognised and they were soon recruited for the Dams Raid by Guy Gibson, under whom Johnson had served earlier in his career

Considered one of the 'grandads of the Squadron', Johnson soon made a valuable contribution to the overall operation when inventing the 'Johnson Sight' which would be used to great effect to provide the precise delivery of the new invention of Barnes Wallis - namely his bouncing bomb

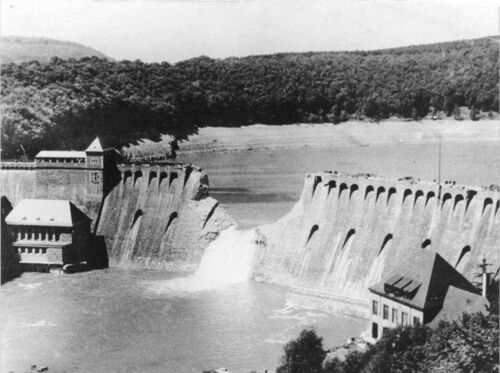

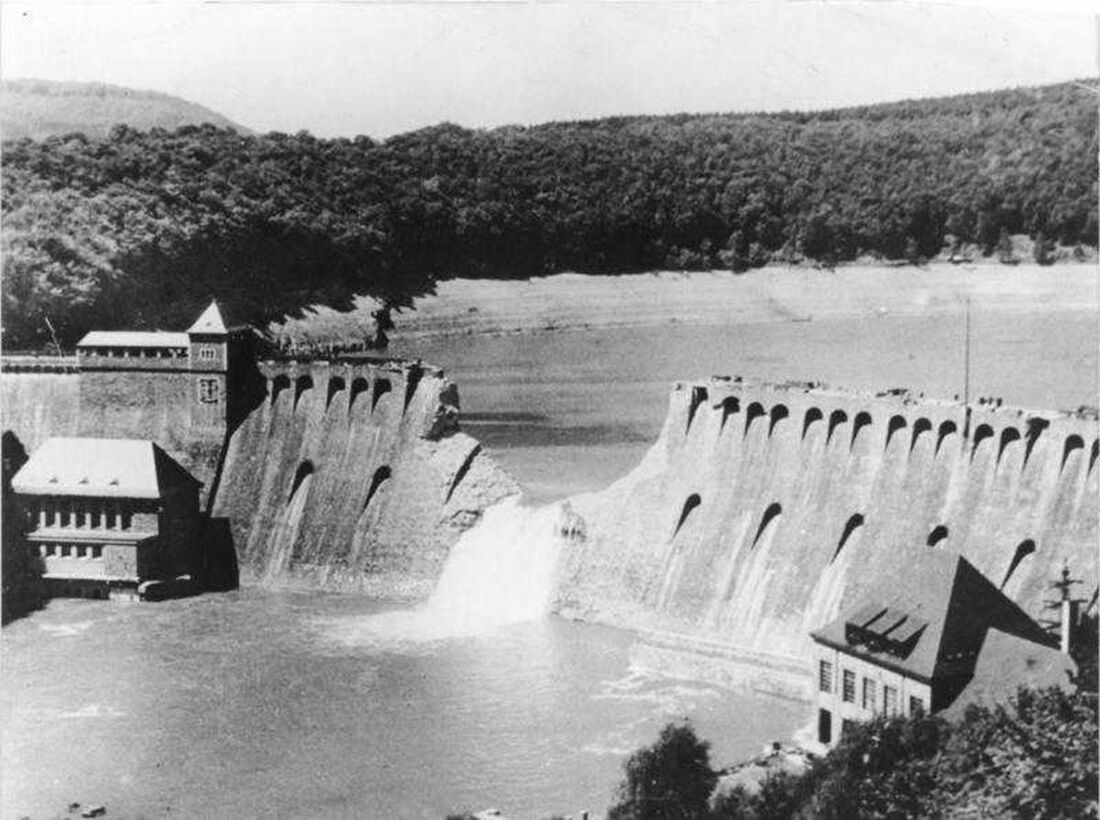

On that famous night Johnson was part of the main Strike Force under Gibson himself and was a witness to the breaching of the Möhne; his opportunity soon presented itself when Knight's crew were called to centre stage

They made several low-level dummy runs into the Eder Dam, each pass being a hair-raising event of high danger due to the steep climb required to bring the aircraft away from the surrounding terrain; their final run was pitch-perfect and Johnson delivered his Upkeep with total precision to score the direct hit that breached the Eder Dam, earning his immediate D.F.C. in the process and also keeping a remarkable souvenir from that night

Recovered from '...the biggest party of all time', Johnson would be required to take to his parachute to save his life during the costly raid on the Dortmund-Ems Canal (Operation Garlic) in September 1943, making his way back to London after assistance from the good folk of Holland, Belgium and France and their underground networks

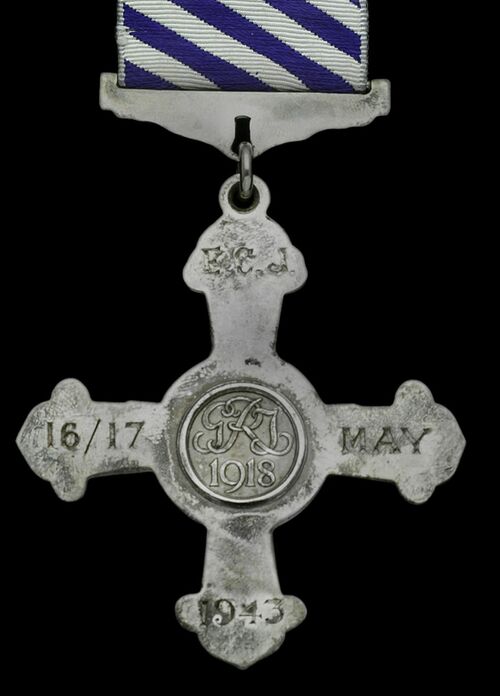

Distinguished Flying Cross, G.VI.R., the reverse officially dated '1943' and additionally inscribed 'E.C.J. 16/17 May', on its investiture pin; 1939-45 Star; Air Crew Europe Star; Defence and War Medals 1939-45, the campaign group mounted as worn, good very fine (5)

D.F.C. London Gazette 28 May 1943:

'On the night of 16th May, 1943, a force of Lancaster bombers was detailed to attack the Mohne, Eder and Sorpe dams in Germany. The operation was one of great difficulty and hazard, demanding a high degree of skill and courage and close co-operation between the crews of the aircraft engaged. Nevertheless, a telling blow was struck at the enemy by the successful breaching of the Mohne and Eder dams. This outstanding success reflects the greatest credit on the efforts of the following personnel who participated in the operation in various capacities as members of aircraft crew.'

The original Confidential Recommendation for the award - in a joint Recommendation with Knight and Hobday - state:

'Pilot Officer Knight was Captain, Flying Officer Navigator and Flying Officer Johnson Bomb Aimer of an aircraft detailed to attack the Eder Dam.

By making several dummy runs over the target at extremely low level, until they were quite certain that their mine would hit the objective, they subjected themselves to constant risk, but by skill of high order on the part of the pilot and by excellent timing on the part of the Air Bomber, and the Navigator, they succeeded on the last run in breaching the Dam.

I strongly recommend that the outstanding work of this crew be recognised by the immediate award of the Distinguished Service Order to Pilot Officer Knight, and of the immediate award of the Distinguished Flying Cross to Flying Officers Hobday and Johnson.'

Air Chief Marshal Sir Ralph 'Cocky' Cochrane concurred with the recommendations and the awards were thus signed off by Air Chief Marshal 'Bomber' Harris.

Edward Cuthbert Johnson - or Johnnie' to his friends, family and comrades - was born at Lincoln on 3 May 1912 and was just two years of age when his father was killed in action on the Western Front in December 1914. As a result he moved with his mother to Gainsborough and was educated at Lincoln Grammar School.

In the period that followed Johnson found employment as a Woolworth trainee and later as a wholesale salesman with Joe Lyons. In 1936, he married May Beckwith, whose family moved from Leeds to Blackpool and established a boarding house business before the outbreak of the Second World War.

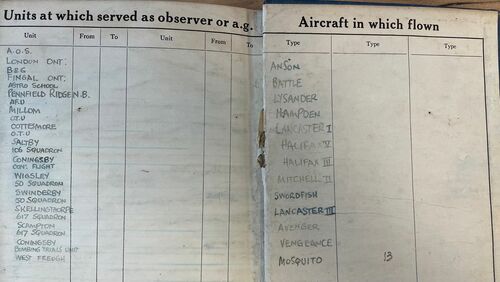

Skyward - First Ops

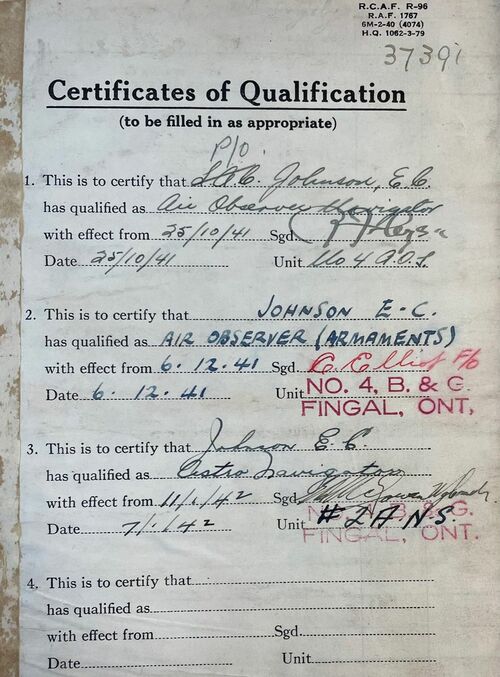

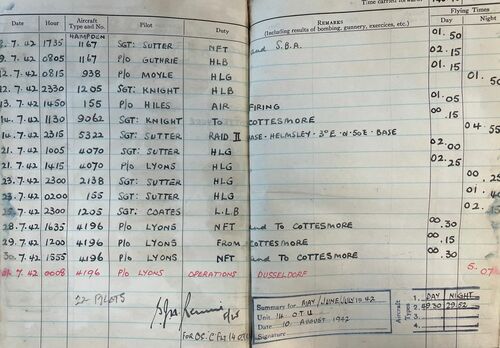

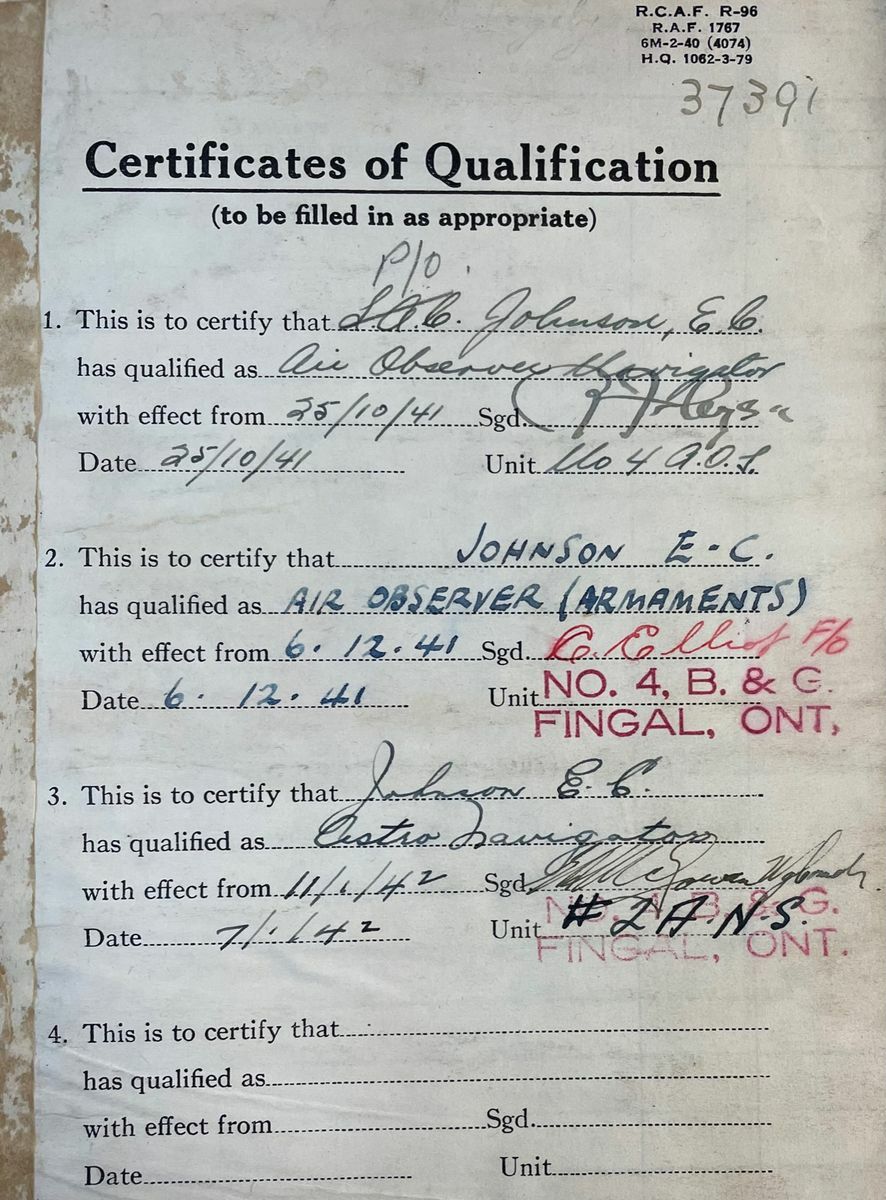

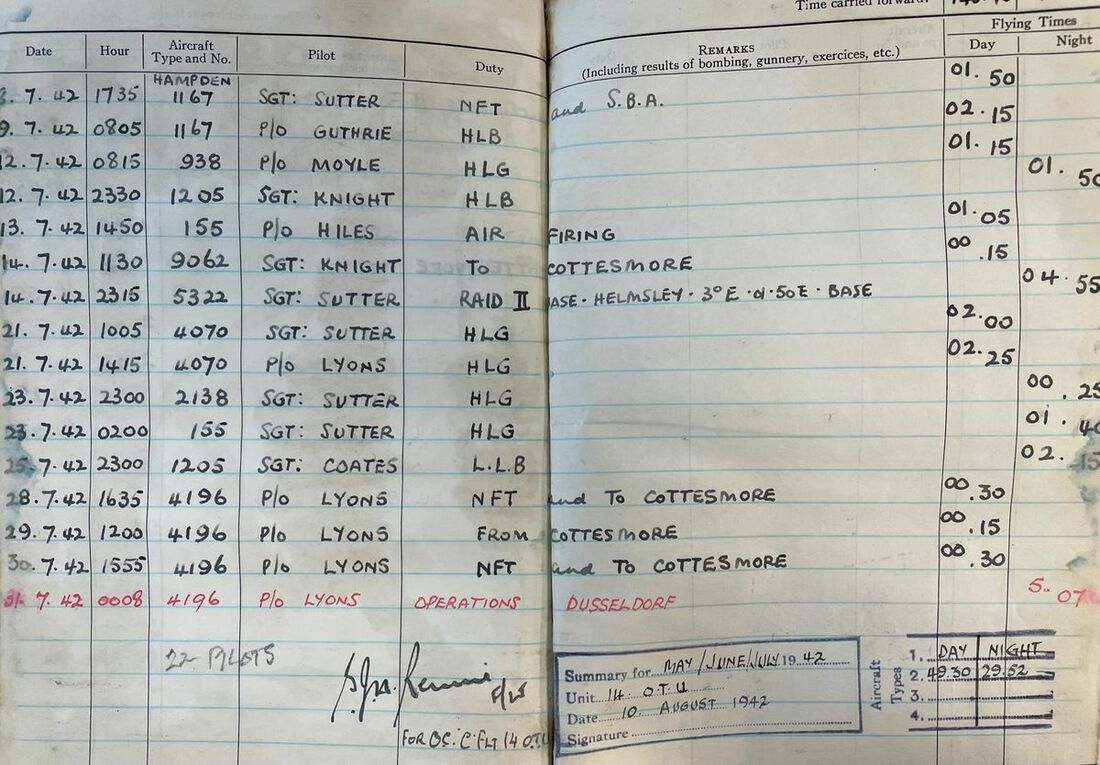

After enlisting in 1940, he went over to Canada for instruction and qualifyied as an Air Observer Navigator on 25 October 1941 and as a bomb aimer on 6 December 1941. Passing as an Astro Navigator on 7 January 19142, Johnson was commissioned at the beginning of 1942 he flew his first Op in Hampden 4196 with Pilot Officer Lyons on 31 July 1942. This was a raid on Dusseldorf and was completed whilst he was still with No. 14 O.T.U.

Johnson served with No. 106 and 50 (Lancaster) Squadrons. In September 1942 he had 'crewed' up under Sergeant Les Knight and flown with him for the first time in Lancaster 7540. Knight had been born in Camberwell, Victoria in 1921 and was serving with the Royal Australian Air Force. The crew would remain together for the fateful events that would follow and formed that unique bond amongst comrades. Despite the fact he was unable to ride a bicycle or drive a car, Knight would prove to be an exceptional Pilot in whom they all put their full trust.

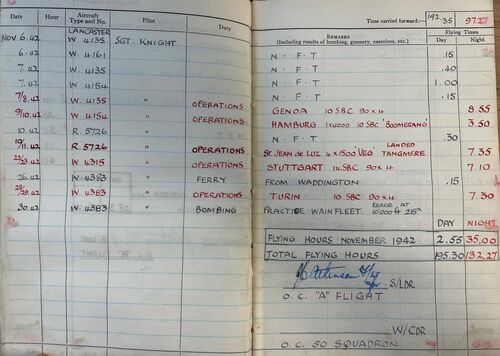

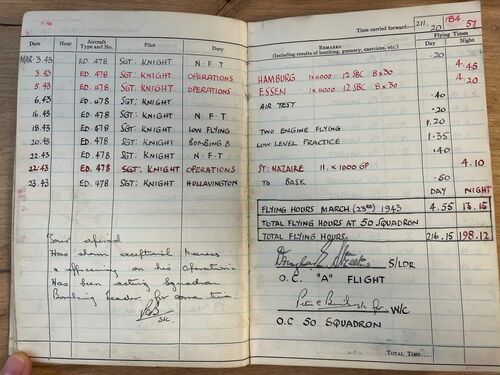

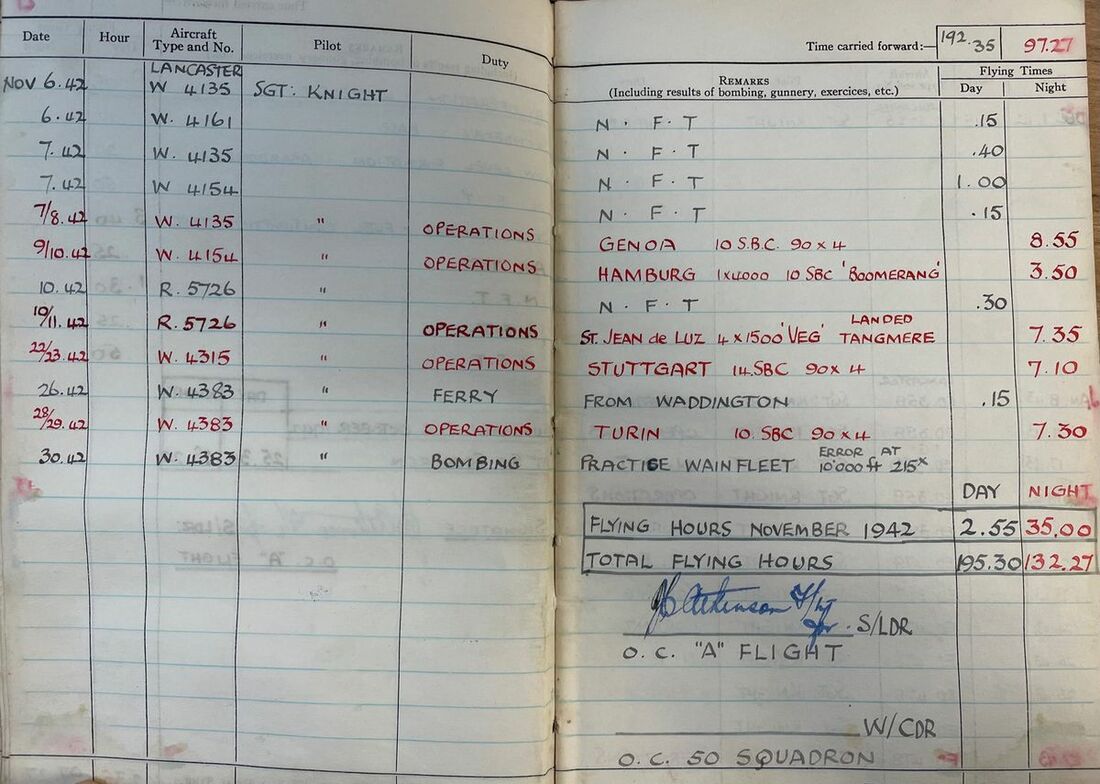

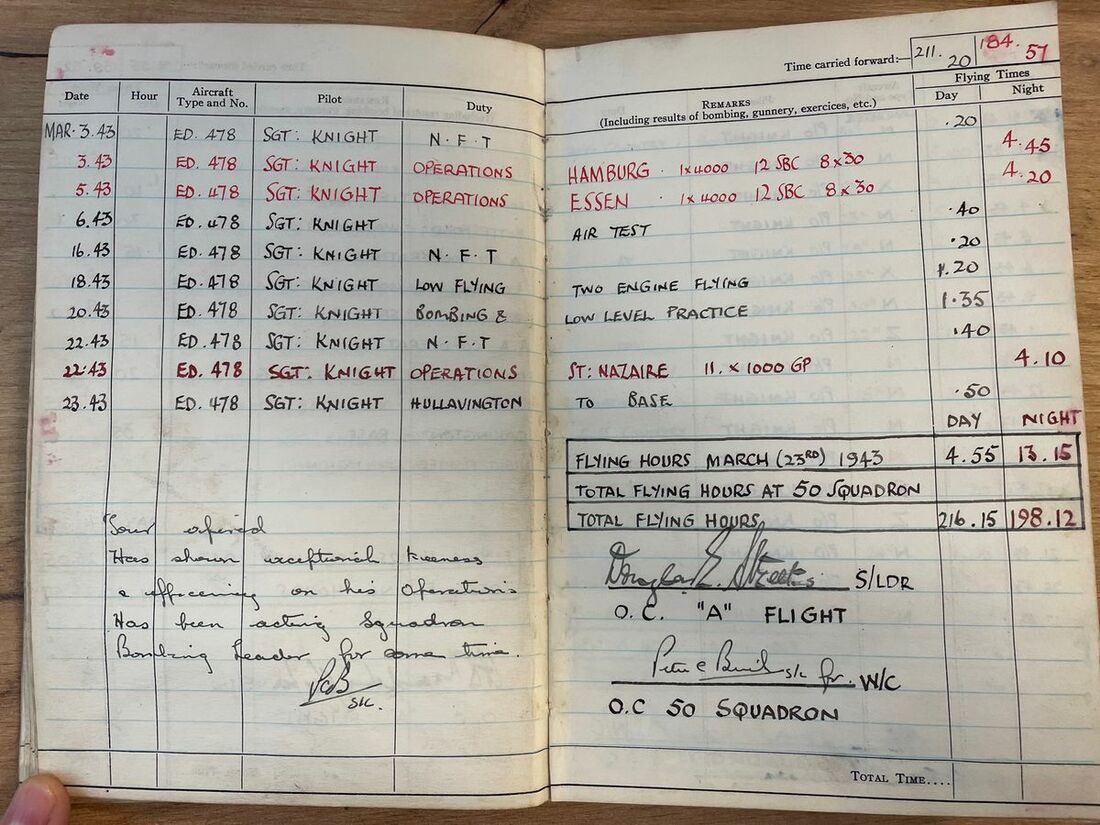

October 1942 saw the crew fly on three Ops, before notching up five more in November, namely raids on Genoa, Hamburg, St. Jean de Luz, Stuttgart and Turin. The same number followed in January 1943, twice rounding on Essen, before making for Berlin -The Big City - on 17/18 January, before closing out with Ops on Dusseldorf and Hamburg. The pace remained high and Johnson flew his final Op on St Nazaire on 22 March. Tour Expired, his CO gave a glowing review:

'Has shown exceptional keeness & efficiency on his Operations. Has been acting Squadron Bombing Leader for some time.'

Higher calling - No. 617

Despite having fulfilled their duties, Johnson and his crew were clearly keen to see more action and a fateful opportunity presented itself. None other than Guy Gibson approached Les Knight and the crew to select them to join No. 617 Squadron. Johnson himself gives some insight in Max Arthur's Dambusters, A Landmark Oral History:

'I volunteered for the RAF and was accepted to train as an Observer, which was a general category then for navigation, gunnery, wireless – but later split into Navigators, bomb-aimers and separate trades. So then I trained as an observer and got my flying ‘O’ badge.

I met up with this crew at 50 Squadron, some of whom I knew, and they needed a bomb-aimer, so with Group’s permission I went flying as a bomb-aimer.

We’d just finished a Tour of Ops with them and we had a good reputation for getting there and getting back – and we were more or less invited to join 617 Squadron. Everybody in the crew was in agreement to going because we didn’t want to split up – which is what happened if you finished a tour and had to go on training duties, you’d probably come back with a new crew – which none of us fancied at all. It seemed a good move to keep on flying together.

Initially nobody knew what the role of 617 Squadron was to be. There were all sorts of rumours flying about – about it being for special duties – but nobody had the vaguest idea what it was actually going to do. All the people joining it were very experienced pilots – mostly decorated or having done one or two Tours of Operations, so it was obviously something rather special to have all these well-known bods.'

On their home base:

'Scampton was a typical pre-war aerodrome with good hangars and good accommodation – and a nice mess. The only drawback to it was that it was a grass field with no runways. But certainly it was a first-class aerodrome.

We were a mixed crew of young and older men – of practically all nationalities. The pilot was the Australian, Pilot Officer Les Knight, and very young – just twentyish. The rear gunner and mid-upper gunner were both Canadians and very young too – one nineteen and the other twenty or so. The wireless operator was also Australian and the navigator and I were British – and we were much older than the others in the crew. But there was never any difficulty about that. Relations among the crew were excellent and all of us very mixed characters got on very well together. Les Knight didn’t drink or smoke and was a bit religious, while the two Canadians liked to drink, and so did I – and the others. But the pilot always went with us and had a lemonade, and this proved important as time went on. The pilot, navigator and bomb-aimer were all commissioned and the rest were sergeants, but we all mixed socially.'

Hobday on the crew:

'I reckon we were a first-class crew. The CO of our previous squadron, 50, used to call us ‘the Ace Crew’. The mid-upper gunner was an absolute ace at shooting – but we were all very dedicated – and all very young except the bomb-aimer, Johnson, and myself, who were the oldest in the crew. I was thirty-one, as was he, so we were like the granddads of the Squadron, because thirty-one was pretty old for aircrew in those days.

We were quickly taken over to Scampton and met Gibson – had a bit of a mess party that night – the first night we were there. After that we knuckled down to some very serious training.'

Johnson offers good insight into Gibson himself:

'I had met Gibson previously at 106 Squadron, where he was the CO. He was very efficient, very straightforward – and I think everybody liked him. He wasn’t a bully or a show-off, but he liked things to be done right, and he also liked you to keep fit (sometimes a sore point) with runs round the aerodrome and so on. After a night out on the tiles these weren’t always frightfully popular – but I think he was on the right lines.

He was strict about work, but he was a great mixer – not so much during the working day, but always at night – he could sup his ale with anybody.'

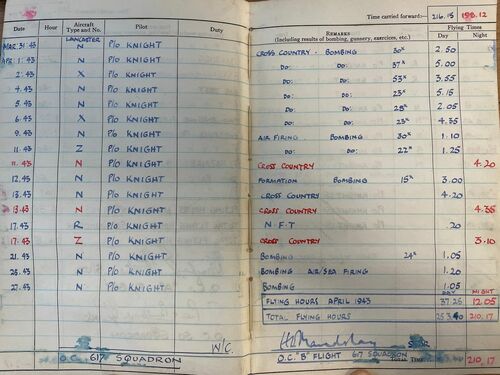

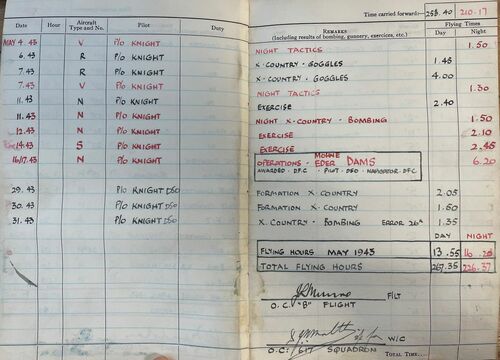

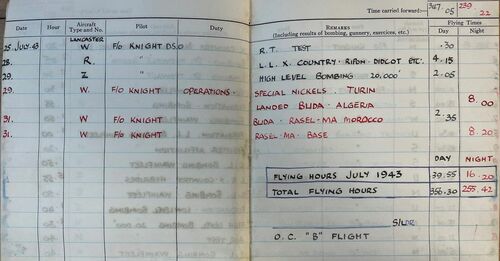

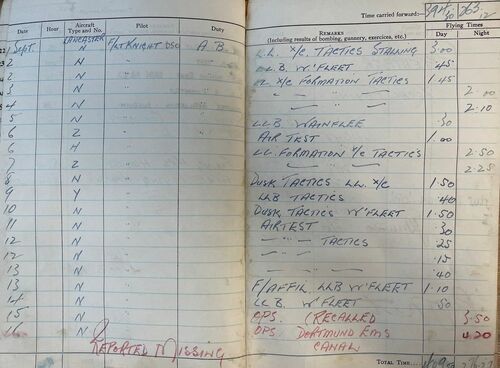

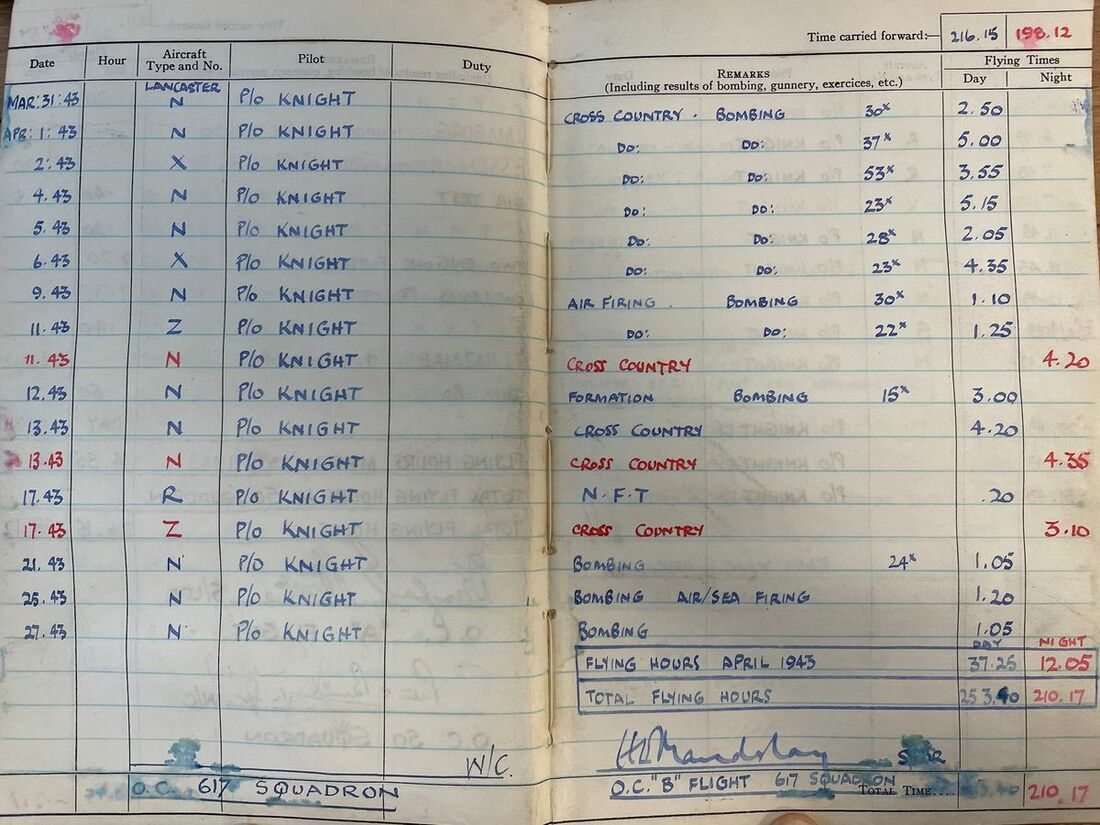

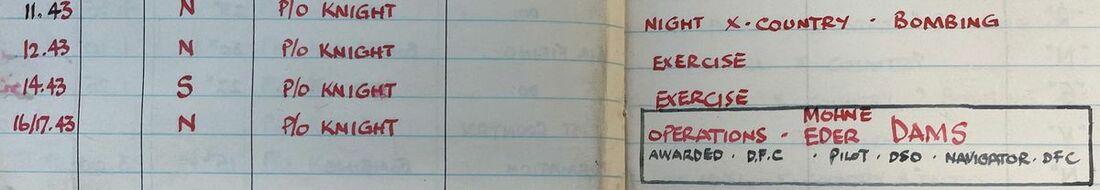

Johnson and the crew first flew with No. 617 on 31 March 1943, we now know they had just six short weeks to prepare before they would play a central role in perhaps the most famous Operation ever completed by the Royal Air Force. His Fly Log Book evidences the testing period of training which was undertaken to perfect their skills. From 31 March-11 April they shared in eight training Bombing training sorties. Johnson continues:

'We worked to get used to flying at low level in very big aircraft – in daylight, then at night. At first this was simulated night with screens blocking the natural light and wearing dark glasses, leaving just one fellow who could see out in case anything went seriously wrong. This was usually the flight-engineer. He didn’t wear the glasses so he could see out in case anything came up that the pilot hadn’t seen, so he could warn him of any danger. Then finally we went flying at night – and then in formation at night. As far as I was concerned, I had to learn a new bombing technique, because there was no bomb-sight of any consequence that could operate at the height we were going to have to operate. It meant doing a lot of low-level bombing to develop techniques to drop the bombs – which was made more difficult because we didn’t know the target.'

His Flying Log Book twice makes reference to daylight X-Country sorties with 'GOGGLES'. The fact that the Squadron didn't know their target also made life very difficult. Guy Gibson on the issues of low-level flying over water:

'We tried to get practice by judging height. To do this we put a couple of men on the side of a hill overlooking a lake with a special instrument to measure aircraft height. One by one we dived over the water and were told afterwards whether we had been right or wrong. This was all right for daylight, but proved impossible at night. Then one day the problem was solved. Mr Lockspeiser of MAP paid the SASO a visit. He said, ‘I think I can help you.’ His idea was an old one – actually it was used in the First World War. He suggested that two spotlights should be placed on either wing of the aircraft, pointing towards the water where they would converge at 150 feet. The pilot could see these spots, and when they merged into one he would then know the exact height. It all seemed so simple, and I came back to tell the boys.

A party of men descended on our workshops and all the aircraft were fitted within a matter of days. Night after night, dawn after dawn, the boys flew around the Wash and the nearby lakes and over the aerodrome itself at about 150 feet, while others with theodolites stood on the ground and measured their heights. Within a week everyone had got so good that they could fly to within two feet with amazing consistency – but as I stood there and watched them with their lights on, I knew that whatever losses there might have been before, we were certainly going to make it easier for the German gunners flying around with lights on.'

Johnson also made a personal contribution to the overall mission. James Holland's Dam Busters, The Race to Smash the Dams, 1943 continues:

'There were also a number of technical issues that needed resolving, and resolving quickly.

The first related to bomb-aiming. He had been making enquiries, because he now knew after his second visit to see Wallis that the Upkeep would have to be released at a fairly precise distance from the dam, but there was no bombsight in existence within the RAF that would work for an operation of this kind. On 2 April, however, he had been in his office when he suddenly received an unexpected visitor. This was Wing Commander Dann of the MAP, who immediately began telling him about the sighting difficulties on the Möhne and Eder dams, and warned him that a new anti-submarine bombsight would not do either.

Gibson, who had repeatedly stressed to everyone the importance of security, was absolutely horrified to hear Dann talking about the dams so openly.

‘How the hell do you know all this?’ he snapped.

Dann explained himself. He was, he told Gibson, the Supervisor of Aeronautics at the Aircraft and Armament Experimental Establishment, and had been told about the project specifically so that he could help. He had spoken to no one about it. Gibson began to calm down and to listen to what he had to say. Taking out a piece of paper, Dann began drawing various lines and at first Gibson wasn’t sure what he was driving at. But eventually he realized Dann was describing a very simple range-finder. Aerial photographs of the Möhne and Eder had shown there were two towers on each, which proved to be around 600 feet apart. It should be possible, Dann explained, to build a simple triangular device, like a two-pronged fork. The bomb-aimer would look through an eyepiece at one end and on each of the prongs would be a nail. By working out the scales mathematically, it would be possible to make the device to precisely the right scale so that as they approached the dam, when the two nails lined up exactly with the two towers, that would be the exact distance to drop the Upkeep. It was simple, but ingenious. Gibson called in one of his ground personnel and asked him to make one right away. ‘Within half an hour,’6 noted Gibson, ‘the instrument section had knocked up the prototype of the bombsight.’

That afternoon he took Dann up to Derwent Reservoir, where there were also two sluice towers. The trial showed the simple wood device worked well, and, having landed back down at Scampton, Dann headed back to London, one problem seemingly solved. Gibson was delighted and told Bob Hay, the Squadron Bomb Leader, to brief all the bomb-aimers about the device.

These wooden, hand-held bombsights were quickly made and handed out, while at Wainfleet poles were rigged up to simulate the towers – not that the crews knew what they represented. They also used the two sluice towers on the Derwent Reservoir for aiming.

George Johnson found the device worked well for him, but not all the crews were happy with it. Len Sumpter, bomb-aimer in David Shannon’s crew, found that, when trying it out, he could not keep his arm steady. There was the vibration and movement of the Lancaster, and he had one hand over the bomb-release button, and at the same time was trying to hold the device. He talked it over with Les Knight’s bomb-aimer, Johnson, and they worked out an alternative. The Perspex on the vision panel was held in by screws. They realized they could loosen these, tie a bit of string around each screw, then tighten them again. On the Perspex itself, they used a grease pencil to make two marks. They then brought the string back to their eye to make a triangle like the wooden bomb sight. This could be adjusted to exactly the right depth from the target, then when the marks on the Perspex lined up with the flags at Wainfleet, they knew when to release the bombs. ‘This worked just as well,’ says Len Sumpter. ‘And you could lean your arm on the arm rest, and just lie there with this against your eye, without wobbling.’

So the 'Johnson Bomb Sight' came to be. It would not have to wait long to see action, although Johnson had the final word on its invention:

'We worked to get accuracy, dropping the bombs at low level by eye, judging the distance. Our height and speed were pretty well fixed, so you got used to gauging distance for releasing the bomb. This changed as soon as we knew the type of target – we were able to think about how we were going to make these distance judgements.

The way they worked out was to have a T-shaped piece of wood with two pins on the end of the T and an eyepiece on the stalk of the T which formed a triangle which represented the triangle made by the towers on the dam walls. I personally didn’t use this method – I found it clumsy and inconvenient and not very accurate.

I developed my own technique of using a long piece of string, fastened each side of the clear bombing panel, and some marks on the panel itself in grease pencil, which did two things when the time came to do the raid. It enabled me to have two marks – one to suit the Möhne tower distances and another to suit the Eder tower distances – which weren’t the same.

I believe it goes the rounds that Flight Sergeant Sumpter also claimed to have invented the string device, but I think he was a little bit later than me using it. It worked very well because I had a bigger triangle than the official one, and it was stationary rather than having to be held.'

The training continued to ramp up:

'We had a few scrapes in training – like picking up treetops. That was fairly common when flying so low. But this didn’t do much damage to the aircraft – sometimes a few branches got sucked up oil coolers, but it was nothing serious. The low-level flying was frightening at the beginning, but it’s surprising how accustomed you become to these things. You begin to think it’s normal and you adjust yourself to the new circumstances. We didn’t consider it hazardous by the end.

There were certain areas that were stipulated by the Air Ministry as being OK for low flying, so we did quite a lot of preliminary bombing training at the Uppingham Reservoir in the Midlands. Sometimes there were complaints from the public – but never to individuals – rather to the Squadron.

There weren’t generally any flying pranks – it was a fairly free and easy squadron, but we all knew that we were doing a job and while we were doing it, we were serious. Afterwards we were a light-hearted squadron – lots of fun and talking and maybe a few pranks in the mess.

The training was serious – and interesting to the nth degree, because it was progressive. You started high and got lower, then you start formation flying – which in itself is quite hair-raising at the beginning. It was fascinating, right to the end.'

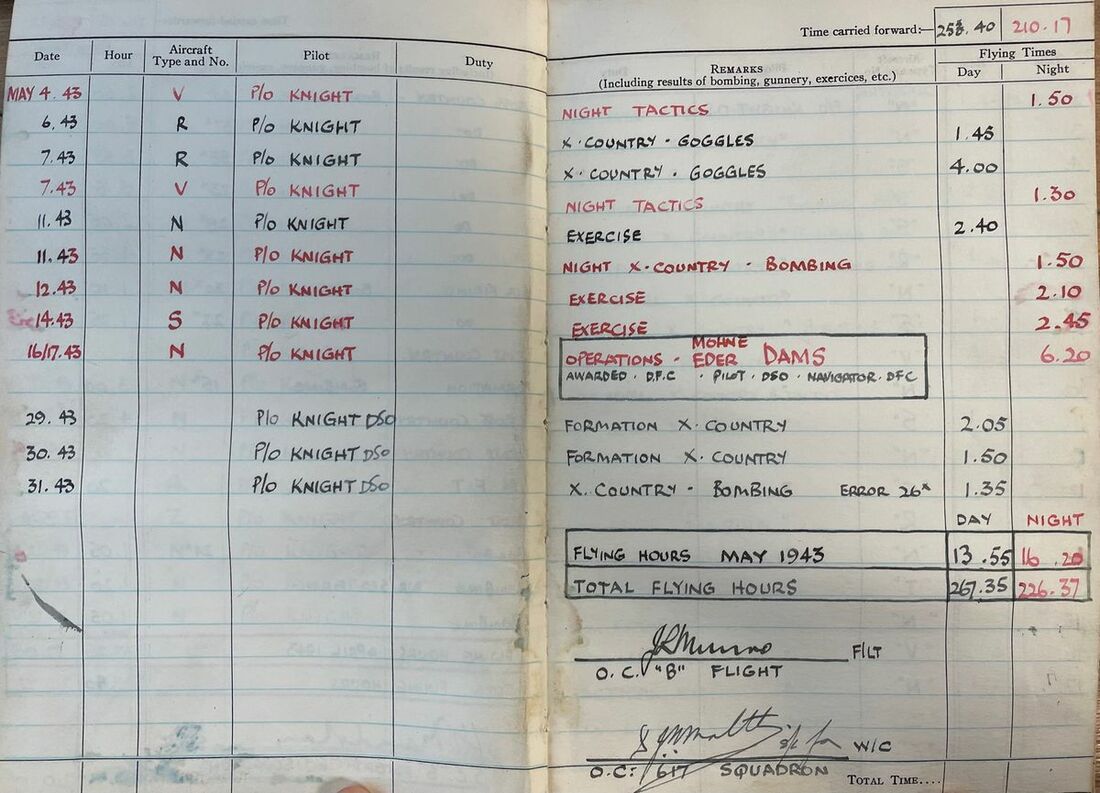

As May rolled into its second week, the Squadron executed two important exercises on 11 May, one at day and the other a bombing practice at night. Two more night Exercises took place on 12 & 14 May. The crews surely knew they were about to be sent forth to strike a blow into the heart of the enemy. The briefing came on the afternoon of 16 May, Johnson recalls:

'We only learned the purpose of our raid on the afternoon before – that was 16 May. Barnes Wallis, the inventor of the bomb was there, along with the CO, Gibson, Cochrane, and a couple of assistants with him as well.

They had models of the Möhne and Sorpe dams and they drew on blackboards, as they did at all briefings, showing the construction of the dams so we could appreciate what was going to happen when the bomb was released. We were then able to look at the models after the briefing to study the terrain and try to identify what we were looking for when we got there. We also had maps to prepare for the route because until then we didn’t know the route we were flying on. Most people adopted a roller-towel technique of cutting up a map out of successive maps and mounting on a roller so that you could unfold it a bit at a time – rather than having a lot of maps all open in the bomb-aimer’s compartment, where you’re not blessed with all that much room. The tracks were marked on that – and perhaps the distances, ten or fifteen miles each side of the track and no more. This saved you from looking at things you didn’t want to see.

This map-reading is quite tricky at low level when you’re whizzing over the ground – features you might see from high up are absolutely no good to you when you’re low down.

Almost everybody spoke at the briefing – the AOC and Gibson, and Barnes Wallis, and the weatherman – a meteorologist. And the wireless operator would be there to say what the wireless drill was to be for the wireless operators. There was a little briefing on the flak situation on the routes we were to take. Not everybody was flying the same route because it was split up into several sections of operation. We were in the main wave – the one that went to the Möhne Dam. If we managed to crack that, we were to fly on to the Eder and attack that.

We could ask questions if there was anything important we couldn’t understand – but there were not many questions. I think we were all a bit overawed at what the target was – it came straight out of the blue. Nobody had the slightest inkling before, and it took them a bit of time to digest what was going on. But it was all hubbub after the briefing was over.

After that most people were giving a sigh of relief that it didn’t seem as dangerous as some of the other targets we’d been thinking about. It was short notice, but I don’t think there was anything lost by that. The training we’d done was totally adequate to cope with what we were given at the briefing – and I don’t think anything would have been gained by briefing us earlier. It would certainly have been bad for security, because there’s always a chance, if it’s out, that somebody will talk about it.

The briefing was in the afternoon and we took off around seven in the evening, so we had perhaps four hours to sort ourselves out and make maps, talk to each other if we wanted to discuss tactics, or what we might do in the event of particular contingencies. We’d plenty of time for that – no rush or panic.

I worked very closely with the navigator, Harold Hobday – we were very close friends, he and I, so we always got on and understood one another very well. Being trained as a navigator and observer meant I understood his problems as well as my own.

Before we took off, if anything we were slightly more elated than usual, knowing it was a very special target that had never been attacked before, and the fact that we were pioneering a low-level attack.'

Hobday on his own take on the briefing:

'Barnes Wallis came along to the briefing and explained the functions and how the bomb was going to work. He described the action of the bomb, skipping along and dropping down just at the parapet – then exploding at a depth of 30 feet – and hopefully the explosion would crack the parapet of the dam itself. He was very enthusiastic about it, and explained it in minute detail, using a blackboard. He drew on it rather than using slides – but we had models of the two dams, and we studied those minutely to try and see what we were up against as regards terrain. On the Eder Dam it was particularly bad because there were hills on both sides which we had to scale, then drop down, and then we had to flatten out to 60 feet. Then as soon as the bomb had gone we had to climb to a thousand feet or so – it was very minute timing needed to get to the right place at the right time and the right height – and then get out of it alive without crashing. Barnes Wallis came across as a very kindly man – very dedicated, frightfully clever – but rather a fatherly type. We were very impressed with him and thought he was a marvellous man – everybody did.

We were absolutely astounded that he could have invented something which was unknown before. There had been nothing like it before, so it was just one of those innovations which one wouldn’t expect. Who would expect a 9,250-lb bomb to bounce on water? I certainly wouldn’t. But we weren’t sceptical – we trusted him implicitly. We never dreamed that it wouldn’t work. After all his efforts we didn’t ever dream it would fail – and it didn’t.'

So they got underway in Lancaster AJ-N 'N for Nuts' and were part of the main attack force under Gibson that headed for the Mohne.

Chastise - Eder Dam breached - D.F.C.

After a thankfully uneventful flight over to the heartland of Germany, Johnson and his comrades in N for Nuts were in the reserve for the first attack that was put into the Mohne. He had a front-row seat for the start of a legendary night of Ops:

'We watched Gibson attack. He went in first, and we were perhaps a bit shattered at the amount of flak there was – rather more than anyone had anticipated. They were very active and kept it up quite stoically after the bombs had started going off, which I thought was quite heroic, because it must have been quite terrifying to be on the dam wall or in the vicinity when things started going off.

We saw the bombs bouncing quite clearly in the moonlight – at that time our bomb was stationary and the others had been starting theirs up successively as their turn came to bomb, to get it going before their attack. When the Möhne Dam was breached, Gibson gave instructions for those who’d actually dropped their bombs to go back to base. The other three, including ourselves, Henry Maudslay and Dave Shannon, went on to the Eder together with Dinghy Young who was Deputy Controller, and went with Gibson in case anything happened to him on the way to the dam, or when he arrived there.'

Barnes Wallis, whose invention was being put to the test was waiting back in the Operations Room at Scampton. The excitement and stress must have been at fever pitch:

'We had a code by which Guy Gibson, in charge of the raid, would Morse back ‘Goner’, every time an aeroplane had dropped a bomb, and if you’ve seen a live bomb explode, you would see an immense column of water that goes up to a height of about a thousand feet. Gibson, after he’d dropped his own bomb, which dropped short and sank short of the dam, would be several miles away and would have seen this tremendous column of water go up – and he’d have Morsed to us, ‘Goner’. And if the dam had broken, then the codeword was ‘N****r’. N****r was Gibson’s dog. We had three messages, ‘Goner’, and obviously the dam wasn’t broken, and I could see Sir Arthur Harris and Sir Ralph Cochrane, who was Commander-in-Chief of Number 5 Group, looking suspiciously at me – and I was thinking it wasn’t going to work – when the very next call that came through was ‘N****r’, and the dam had gone. It must have been a marvellous night for Gibson. He said that after every bomb had exploded, the pilot of the aircraft was to fire a red Very pistol. This immense column of water was mostly spray, and he said it was illuminated blood red by the light of the Very pistol, and you saw a blood red column 1,000 feet high going up. It must have been a very marvellous sight.'

With the first target breached, Gibson and the crews who had bombs left went onto their next target, the mighty Eder Dam. David Shannon gives the best introduction to what came next:

'We flew east-south-east to the Eder Dam. The flight time was only about ten or fifteen minutes, but it was terribly difficult because by now it was well after midnight, and early summer fog was coming up. It was difficult to navigate because the lake had two arms. I ran down the wrong arm to start with and said, ‘I’m not there.’ Gibson was right over the dam by then, and he fired a Very light. We saw that and moved over.

The Eder Dam was not protected by any anti-aircraft defences at all. I think the Germans must have thought it was so difficult for anybody to deal with because of its natural surroundings that it was quite secure. It was way down in a very steep valley, and we were flying there above the hills, above the level of water behind the dam, at about 1,000 or 1,500 feet. There was a castle at one end of the lake over which, we judged from our briefing, that we had to drop down immediately over the side of the hill, level out over the water, go over a spit of sand jutting out into the lake and on to the dam wall beyond that.

The Eder Dam was a bugger of a job. For a start, it was much larger than the Möhne Dam. I was first to go; I tried three times to get a ‘spot on’ approach, but was never satisfied. To get out of the valley after crossing the dam wall we had to put on full throttle and do a steep climbing turn to avoid a vast rock face. My exit with a 9,000-lb mine revolving at 500 rpm was bloody hairy! Then Gibson told us to take a breather and Henry Maudslay went in. On his third run he dropped his mine, and it was the same as with Hopgood: his bomb hit the top of the wall, bounced over, and got the power station below.

Gibson told me to have another run. It seemed pretty satisfactory and we dropped. We made a breach way down under the wall and the rear gunner shouted out that there was a bloody great hole below and the water was pouring out. But the top was still intact. Now only one aircraft remained – Les Knight.'

The following moments remained fresh in the mind of Johnson:

'The first one instructed to attack was Dave Shannon, and he made several attempts, perhaps four or five, to try and get down to the level from the high ground over which we were flying – to get levelled out in time to give his bomb-aimer a chance to get squared up and say, ‘right’, ‘left’, ‘up’, ‘down’ – to get himself in position for dropping. He didn’t succeed, so Gibson told him to stop and rest, just circling, and let the second man, Henry Maudslay, have a try. He had two attempts, I think, and didn’t succeed.

Then we were instructed to bomb and I think we made perhaps three trial runs before we made our final attack. Les Knight was very good and got us down quickly to a low level, and we had a good run-in. I could clearly see the towers and I was quite happy with my bomb-sight and position – and I released the bomb. I forgot all about the bomb from that moment on, because we were flying directly into this large piece of land, which was only just across the river from the dam. Being in the front of the aircraft, it’s quite terrifying to see this looming up at high speed. I was very anxious that we should get pulling the stick back and get over the top which he did, and pushed the throttle right through the emergency gate to get the maximum power – and we skimmed over the top of the hill.

I didn’t actually see the dam burst because I was out of sight, being in the front of the aircraft – but it was obvious what had happened by the noise on the intercom from the rear gunner, and everybody else who could see anything was going mad on the intercom, because the centre had fallen out of the dam and the water was absolutely pouring down this narrow river, causing a veritable tidal wave, and we forgot all about safety and going home and we were trying to follow the water down the river to see what happened. It was a terrifying sight. We could see cars being engulfed, then Gibson called up and said, ‘Well, it’s all right boys, you’re having a good time – but we’ve still got to get back to base. Let’s go.’'

Gibson himself recalls:

'Meanwhile, Les Knight had been circling very patiently, not saying a word. I told him to get ready, and when the water had calmed down he began his attack. He had some difficulty too, and after a while, Dave began to give him some advice on how to do it. We all joined in on the R/T and there was a continuous backchat going on.

Les dived in to make his final attack. His was the last weapon left in the squadron. If he did not succeed in breaching the Eder now, then it would never be breached – at least not tonight. I saw him run in. I crossed my fingers. But Les was a good pilot and he made as perfect a run as any seen that night. We were flying above him and about 400 yards to the right, and saw his mine hit the water. We saw where it sank. We saw the tremendous earthquake which shook the base of the dam and then, as if a gigantic hand had punched a hole through cardboard, the whole thing collapsed. A great mass of water began running down the valley into Kassel. Les was very excited – he kept his radio transmitter on by mistake for quite some time. His crew’s remarks were something to be heard . . . I called them up and told them to go home immediately. I would meet them in the mess afterwards for the biggest party of all time.'

It was time to head back, with one final look at the mess they had created:

'We put everything through the throttle and went back to the Möhne Dam, because that was the approved route for going home. We could see the floods that were forming on the low side of the dam, as the water was still pouring out. We could clearly see that it was emptying – all the sand was showing around the fringes of the lake, even in that short time, and the water was still pouring out in great volume. We could also see that the power station had disappeared below the dam wall. You couldn’t see it at all, and there were all sorts of large lumps of masonry lying about down the valley and water as far as you could see.

We set route from there to go home with full throttle, which the engineer, Ray Grayston, said we could use because we’d got petrol and didn’t mind wasting it. We had a fairly uneventful journey home – nobody shooting at us. We’d been flying for some time then, it was getting quite late in the night, and we were very relieved to see the North Sea and think that we might be home shortly.

When we got back there was a fairly comprehensive debriefing – a fair bit of excitement that we’d been successful in doing at least two of the dams. We didn’t know much about the others at that time, because the waves that were to attack the Sorpe and the Ennepe, and one or two other dams didn’t go off until after us. As it turned out, they didn’t do an awful lot of damage. They were a different type of dam – not the same construction as the Möhne and the Eder, so I don’t think they could have been expected to do too much damage with that type of bomb.

After debriefing we didn’t go to bed – there was a good deal of boozing went on through the night. I haven’t the faintest idea what time I went to bed.'

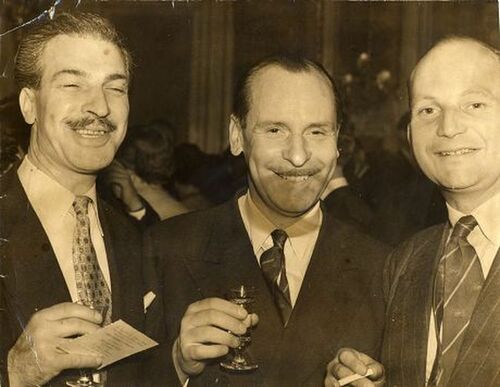

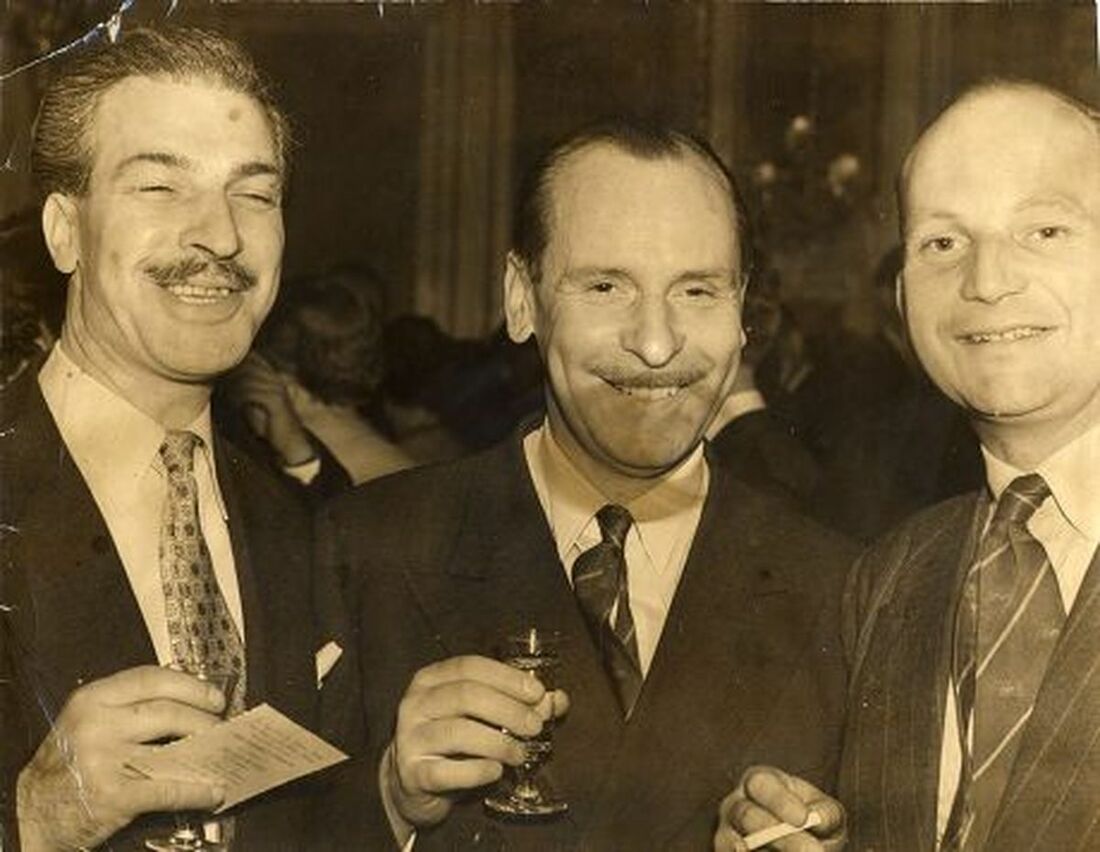

The morning after the night before and surely with a few sore heads amongst those who had lived to tell the tale, the historic photograph of 'The Dambusters' was captured, Johnson is of course present. The human cost of the raid also began to hit home. Of the 19 Lancasters which set out, 8 had been lost, with 53 Airmen killed and 3 more taken a Prisoner of War. Besides that, Guy Gibson's beloved Squadron mascot, his black labrador, was killed by a car that same night. She was buried at Scampton at midnight as the attacks were going in.

The decorations for their remarkable contributions followed the next month, with Johnson going up to Buckingham Palace to receive his D.F.C. from the hands of The King on 22 June with his comrades.

As Les Munro recalled:

'The Squadron then went through somewhat of a hiatus period. We gained the impression that Bomber Command didn’t know what to do with this special Squadron.’

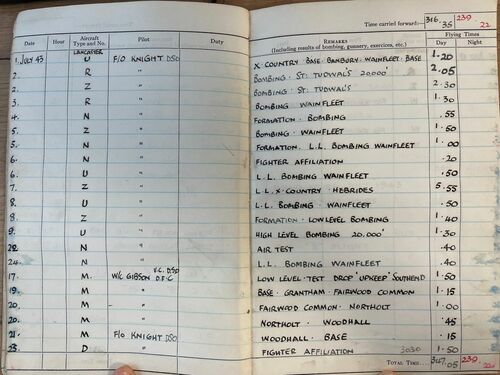

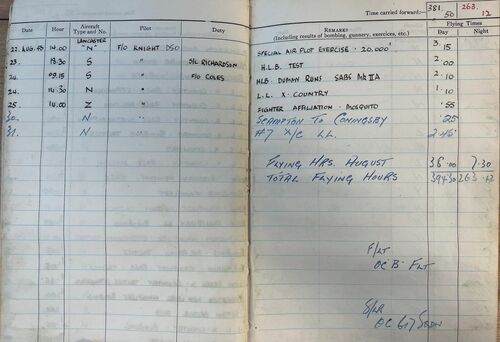

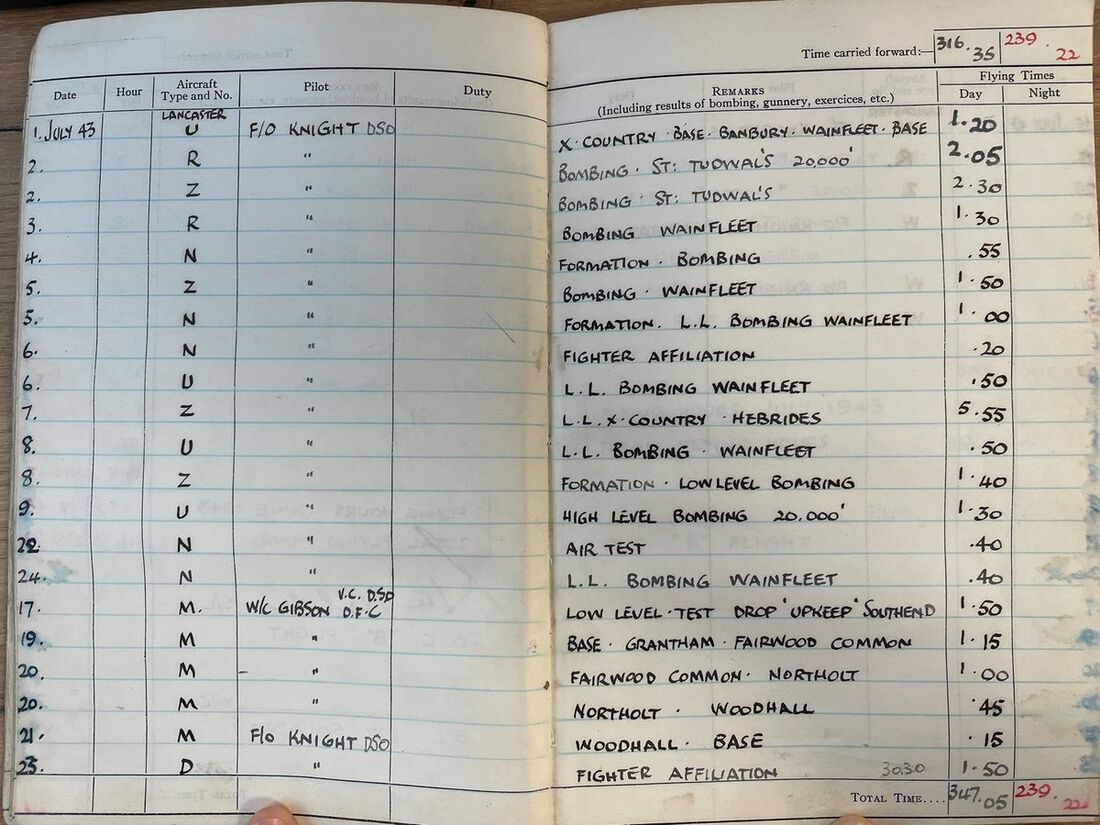

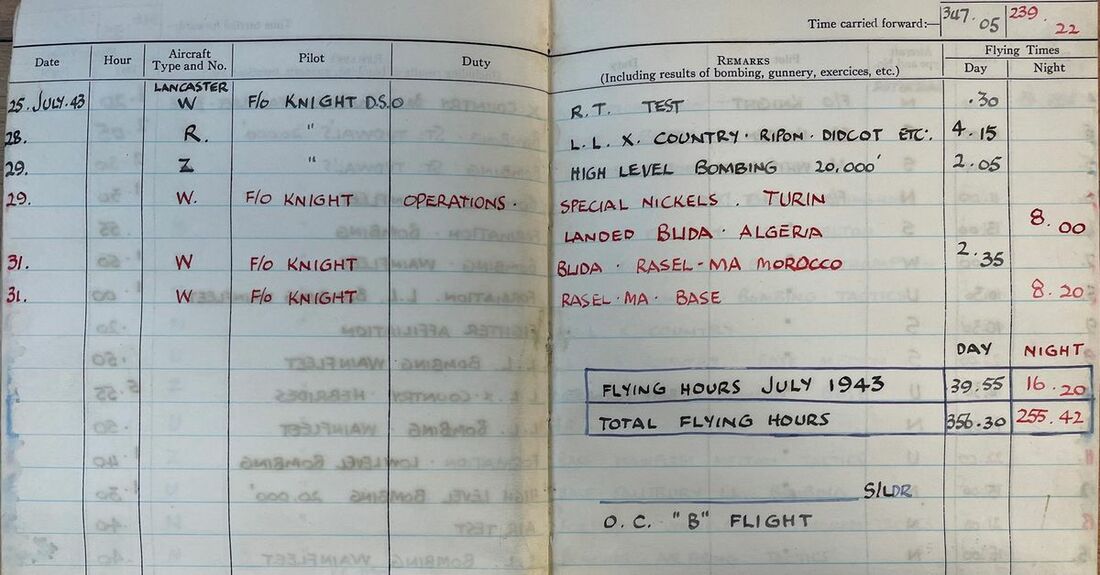

No further operations were flown for two months, with Guy Gibson departed for the U.S.A. and Canada to undertake a lecture tour and Wing Commander George Holden assuming command. Training flights continued unabated however. The crew remained together and undertook a plethora of low-level bombing practice sorties in June and July. Johnson was also selected to crew up with Gibson for a series of four flights on 17-20 July in Lancaster M. No doubt on account of his proven abilities, the Log Book refers 'Low Level - Test Drop 'Upkeep' Southend'.

Once again with Knight at the controls, Johnson flew his next Op on 29 July, dropping 'Special Nickels' on Turin and thence landing at Blida, Algeria. Nine aircraft had set off from Scampton to drop leaflets on Milan, Bologna, Genoa and Turin and all made it to their designated landing spot on Algeria.

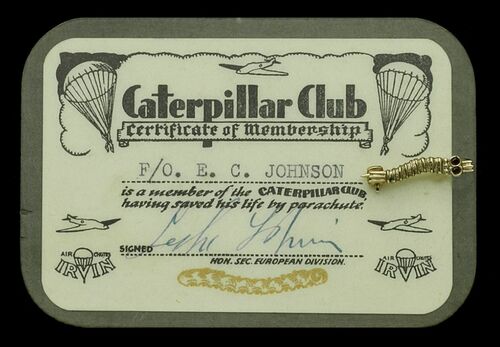

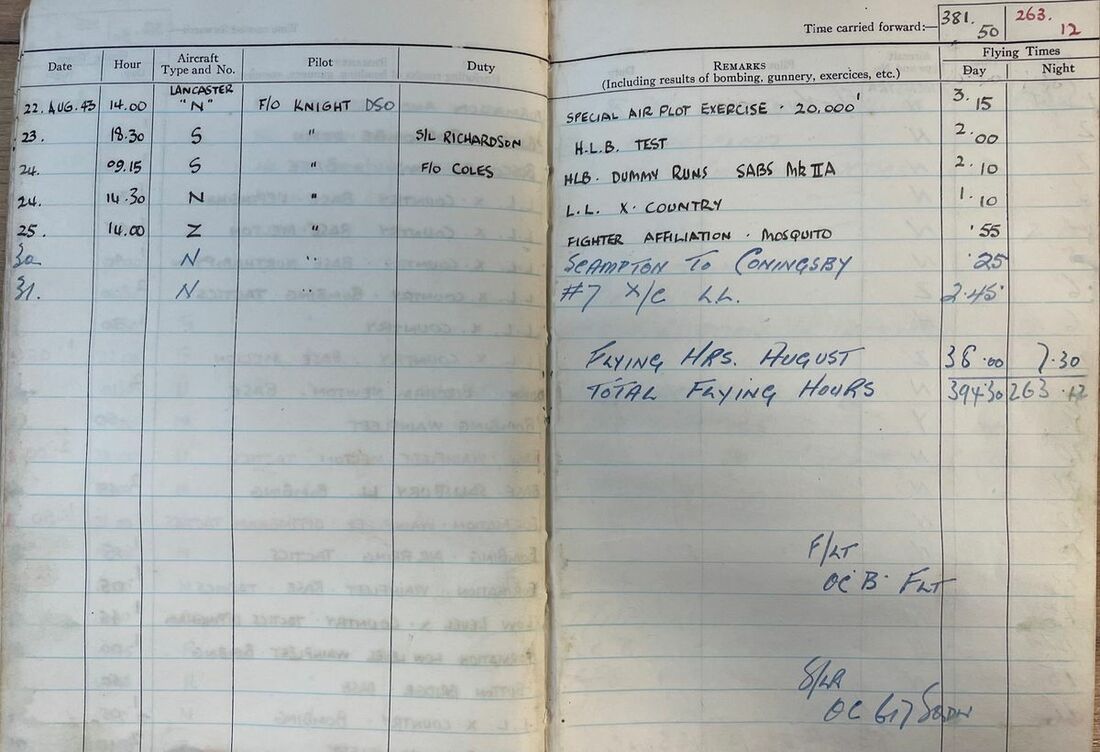

Op Garlic - Caterpillar Club

Continuing to hone their skills, No. 617 were next to be utilised for precision bombing jobs using the 'Tallboy' and 'Grand Slam' bombs. Towards the end of August 1943, they commenced training with the SAB’s Mk. 11A bomb sight, an exercise assisted by Squadron Leader Don “Talking Bomb” Richardson, an expert who flew with each crew on their practice flights. He took to the skies alongside Johnson on 23 August. Moreover, the Squadron transferred lock, stock and barrel to Coningsby on 30 August.

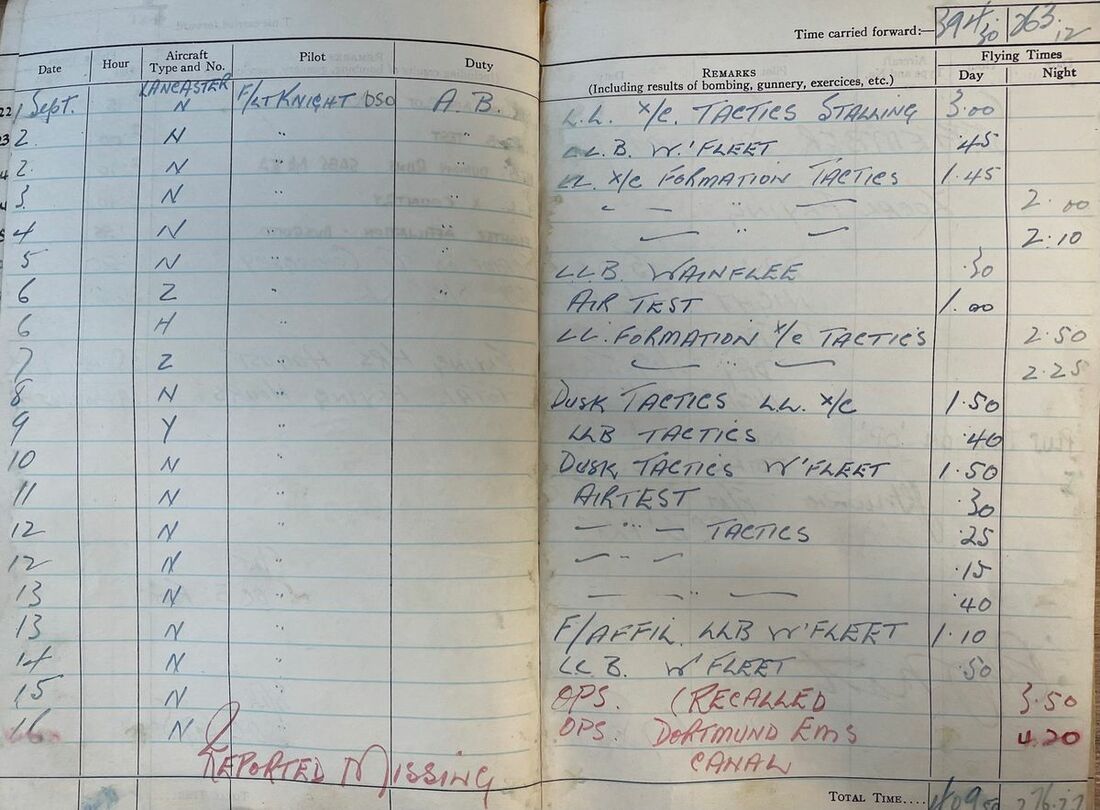

Next in their sights was the Dortmund-Ems Canal, the aim being to deliver 12,000lb bombs to blow the aqueduct on this vital highway for German industry. No surprise that No. 617 got the job.

On 15 September eight Lancasters, with half a dozen Mosquitos for cover set off for the job but found heavy fog over the North Sea. The Op was now impossible and Squadron Leader Maltby, who had famously breached the Mohne Dam just months prior, crashed into the sea with the loss of all the crew. Flight Lieutenant Shannon circled for two hours in vain, with only Maltby's body ever being recovered. Johnson and Knight returned to base.

Flight Lieutenant 'Micky' Martin and his crew had the unfortunate job of stepping into the shoes of the departed Maltby when the Op was re-launched the following night.

It can only be considered as a total disaster, with six of the eight being shot down. Poor visibility hampered them again and despite several bombs going close, it would be another year before No. 617 would drop a 'Tallboy' that finally finished the job.

As for the events of that night, Johnson's Telegraph obituary sheds light:

'Johnson was in the nose viewing the target area in poor visibility when he was horrified to see some trees ahead - and higher than the aircraft.

He yelled: "Up, up, for God's sake up." Knight reacted quickly, but Johnson remembered: "There was a horrible crunching sound as we swept through the tops of the trees at 250 mph."

The situation was dire, with furious flak and fire in two port engines, as Knight, hoping to make it home, coaxed the Lancaster to some 1,200 feet. Johnson had already jettisoned the huge bomb to gain more height and was throwing out guns and all heavy gear to lighten the load.

The bomber had reached the Dutch border when Knight, realising it was impossible to go on, ordered the crew to bale out. He remained at the controls until his crew of six others had jumped but the skipper had left it too late and went down with the burning bomber.

Johnson jumped, yelling: "Cheerio boys. Best of luck. See you in London." He landed in a ploughed field, and recalled: "The farewells were a little hasty but lacked nothing in sincerity for that."'

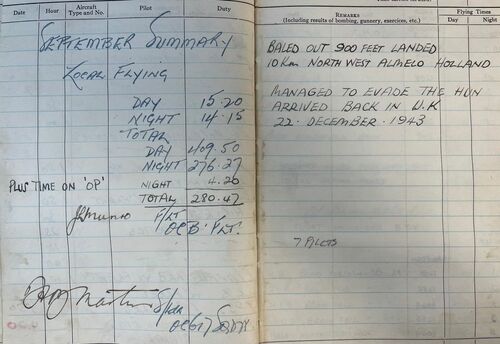

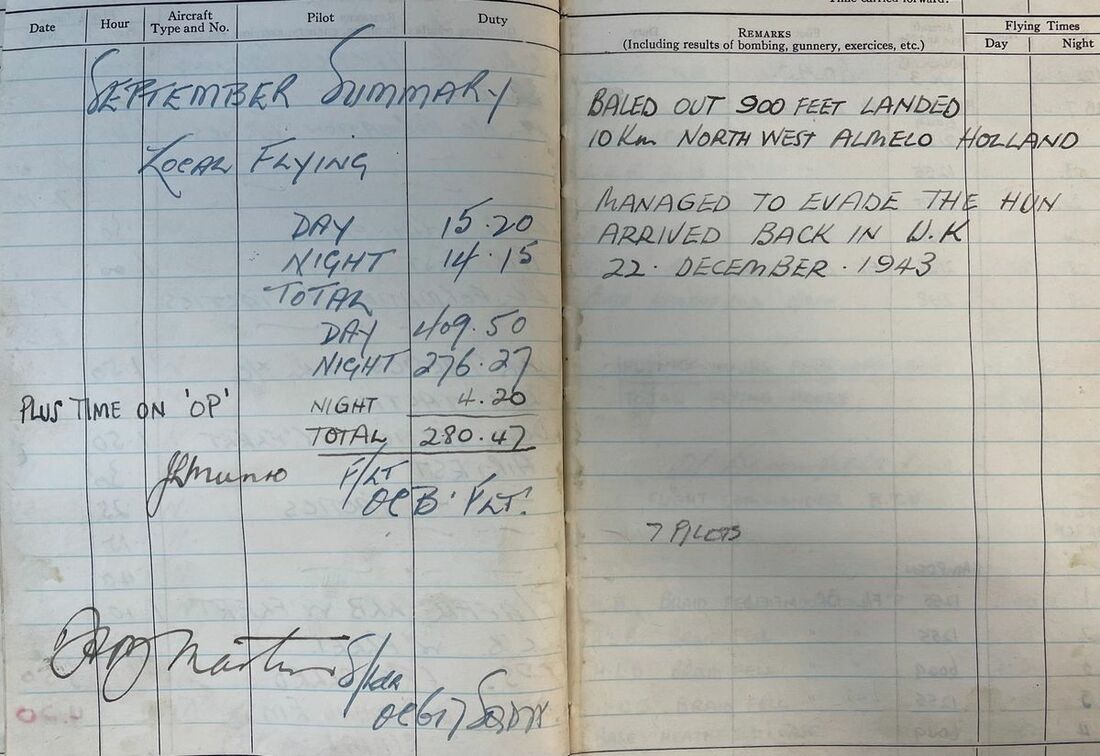

His Flying Log Book records the details which account for his gaining membership to the Caterpillar Club:

'Baled out 900 feet landed 10km North West Almelo Holland.

Managed to evade The Hun arrived back in UK 22 December 1943.'

Upon arriving back he gave the following de-brief to M.I.9. (WO208/5582 refers):

'I remained at the farm near ELST for about five and a half weeks (19 Sep-31 Oct 1943). A bed was rigged up on the upper floor of the barn, and it was arranged that I should hide in the cellar of the barn if the Gestapo made a search. During the day I worked in the orchard. With me was a student from AMSTERDAM who was hiding from the Gestapo, having been in two concentration camps.

The girl, who worked for a Company called NEDERLANSCHEHEIDEMATSCHAPPI, she thought she could help me. She appeared the day after my arrival, and asked me for some particulars, which I gave her, such as name, number, route etc.

That evening, I was visited by a man of about 22 years of age, who said that he would help me to get away and warned me that the girl was not to be relied on. He said that if she returned to the farm I was to hide and the farmer was to tell her that I had left. He took down my details, and throughout my stay here, visited me about twice a week. He also told me that he was in touch with two other R.A.F. men in the district. The girl came about once a week, but was told that I had gone.

After a week, the young man said he was going to UTRECHT to see someone who would be able to help me. When he got there, he found that his contacts had been arrested by the Gestapo. A few days later, he went to AMSTERDAM with the same plan, but found that his contacts there had also been rounded up by the Gestapo.

About 24 Oct the manager of the GRONINGEN branch of the company with which the girl worked - he lived in ARNHEM - asked the farmer where I had got to as none of his organisation had heard of my whereabouts. When I heard this, I came out from where I was hiding and told him what I had heard about the girl. He took down my particulars and promised to get in touch with me in a few days' time.

On 26 Oct two men and the girl arrived. They told me that they had made arrangements for me to go by train to WEERT. On 31 Oct I left for that town with the manager of the WEERT office. I remained here one night at the manager's flat.

On 1 Nov a Dutch policeman, accompanied by a civilian, took me to MAARHEEZE by bicycle, I stayed in a caravan for the night. Here I met several policemen and civilians who belonged to the organisation. The head of the organisation was called VERMAAZEN.

On 3 Nov I cycled across the border into BELGIUM accompanied by VERMAAZEN and a civilian and his wife, We crossed in open country and were not challenged in any way.

We were met on the Belgian side of the frontier by a Customs officer with whom I walked a short distance, until we met a man who supplied me with another bicycle. We then cycled to HAMOT, where I was taken to the house of a local manufacturer called WIJNEN. I was given two rooms at the top of the house. I remained here for about ten days.

On 13 Nov I was taken by cycle to NEERPELT where I stayed with the local shoemaker. Here I met Lt MILLS, U.S.A.A.F. I was provided with an identity card.

On 18 Nov we were sent by train to ANTWERP. We were met at a suburban station by GUSTAVE, who took us by tram to a small cafe near the docks. We remained here for that day, and in the evening, were taken to a flat in the town.

The next day GUSTAVE took us to another cafe called "Du Swan", Klapdoro Street owned by MARCEL MEAZ. We stayed here for two nights. While we were here, we were taken to a store and photographed.

On 21 Nov two men came and said that we would be going to BRUSSELS the next day. We travelled to BRUSSELS with the guide, F/O CLEMENTS (S/P. G. (-)1657) and F/O ELLIOTT (S/P. G. (-)1662). On arrival there we were taken to a house owned by a wealthy widow, whose son works for the Germans and types for the underground movement.

On 24 Nov Lt MILLS, S/Sgt JOHNSON, U.S.A.A.F., and I were taken by train to TOURNAI, and from there to a small frontier village. From here, with several more escapers, we walked across the border into FRANCE. We were escorted by a border policeman in civilian clothes.

We stayed that night at the policeman's house, and were given new identity cards. We also handed in all our Belgian money. On 25 Nov we left by train for LILLE and then PARIS. On arrival, we were taken to a church where we met Mme CHARMAINE and a man with a lot of gold fillings in his teeth.

Lt MILLS and I were taken to an apartment in the rue des Tombes, where we remained for several days. While here we were given new identity cards.

On 1 Dec Lt MILLS, S/Lar PASSY(S/P. G. (-)1630), F/O CLEMENTS (S/P. G. (-)1657) and I left by train for BORDEAUX. From this point my story is the same as that contained in Appendix C to S/Ldr PASSY's report.'

The Telegraph fills in a few gaps and adds detail to his remarkable evasion:

'He buried his parachute and walked until dawn before settling into the top of a haystack in a farmyard and sustaining himself with "escape kit" condensed milk and chocolate. In the morning he removed all RAF uniform insignia and called on the farmer whose family produced hot food.

The farmer equipped him with overalls and shaving gear and Johnson set off on a trek which was to take him through Holland, Belgium, France and Spain, before reaching home from Gibraltar.

In Holland Johnson was helped on his way by a village policeman, who provided a suit, and members of the underground, who couriered him to Belgium and on to France.

There he was sheltered in a Paris flat by a woman trading in black market food. Travelling on in a succession of trains Johnson neared the Pyrenees and cycled until, reaching the hills, he was guided by a smuggler into Spain, where he was picked up by a British Embassy car and driven to Madrid.

After lodging in the embassy Johnson was smuggled across the border at La Linea and on to the Rock, whence he was flown home in a Catalina flying-boat, arriving some four months after baling out.'

Journey's end

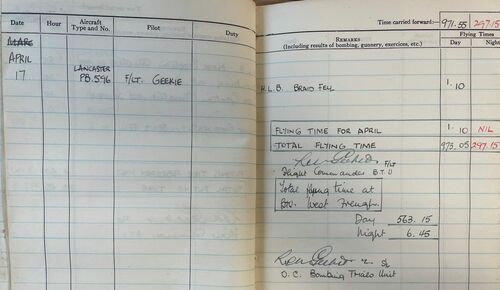

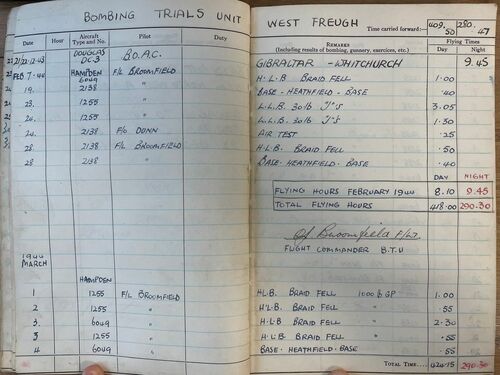

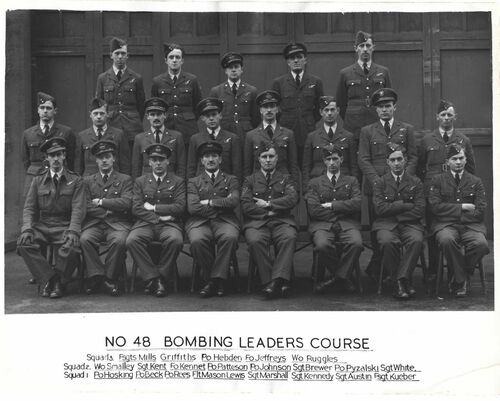

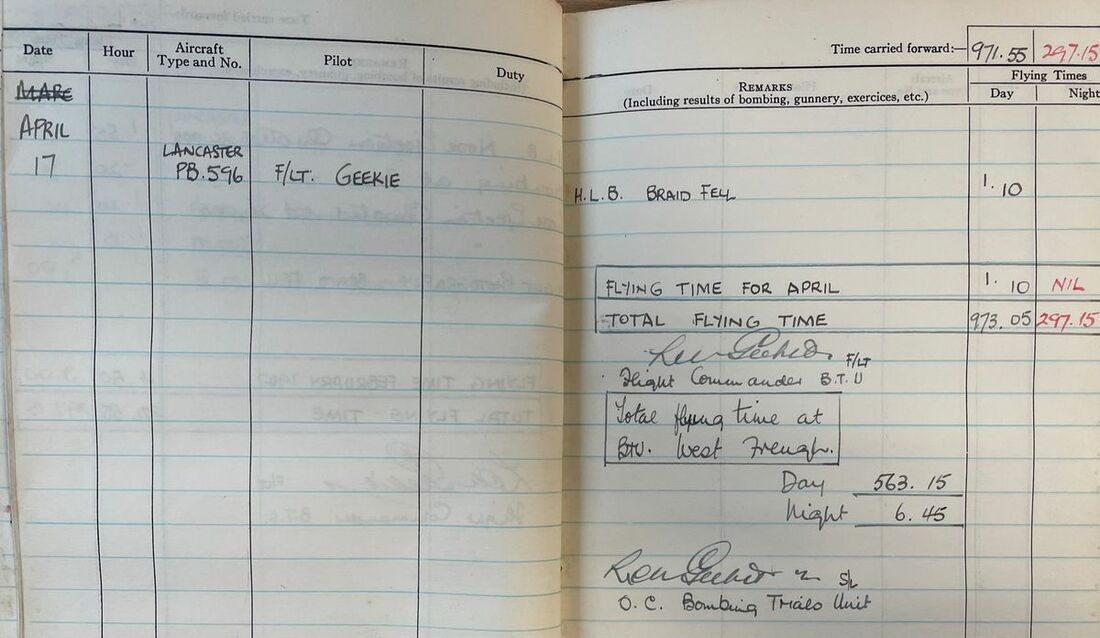

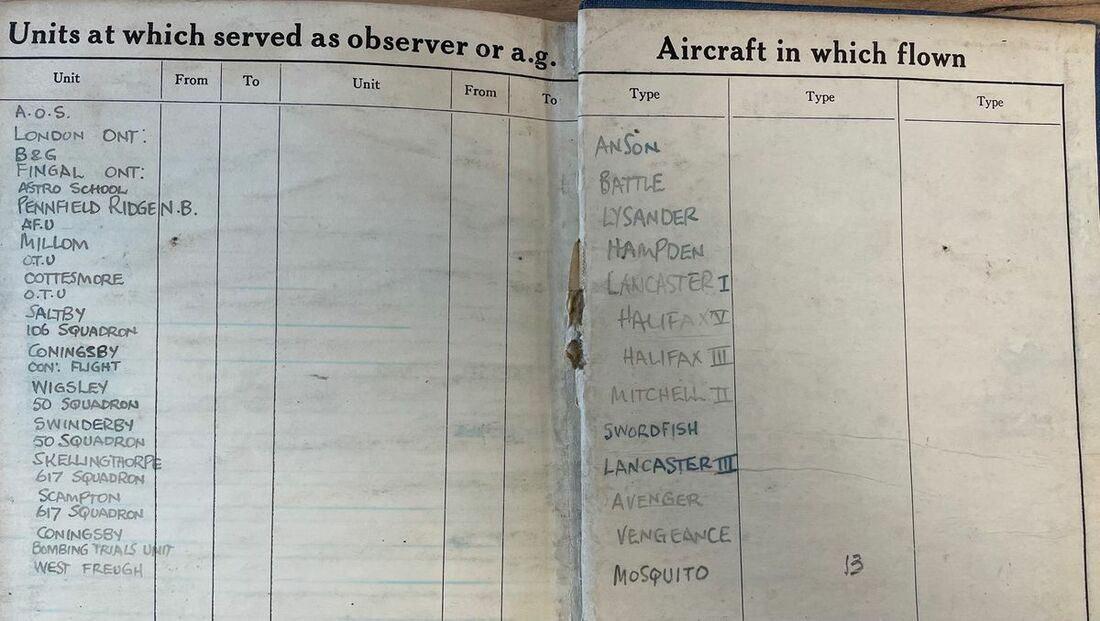

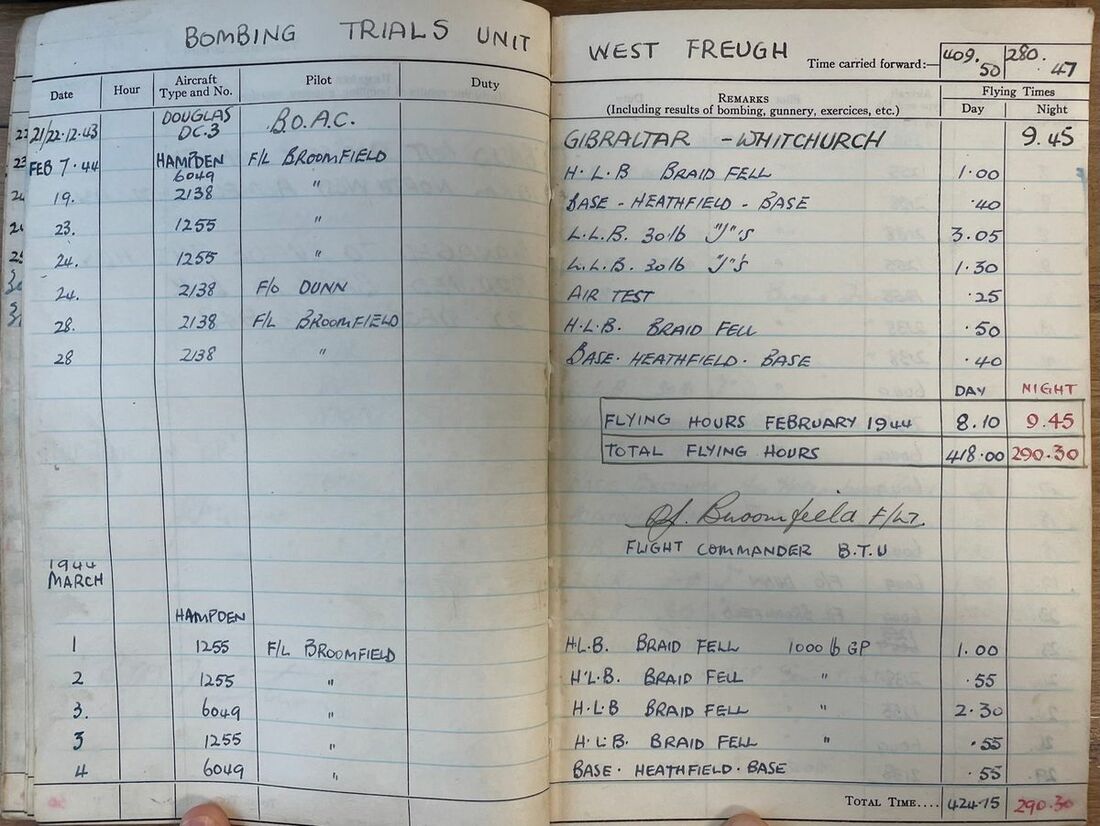

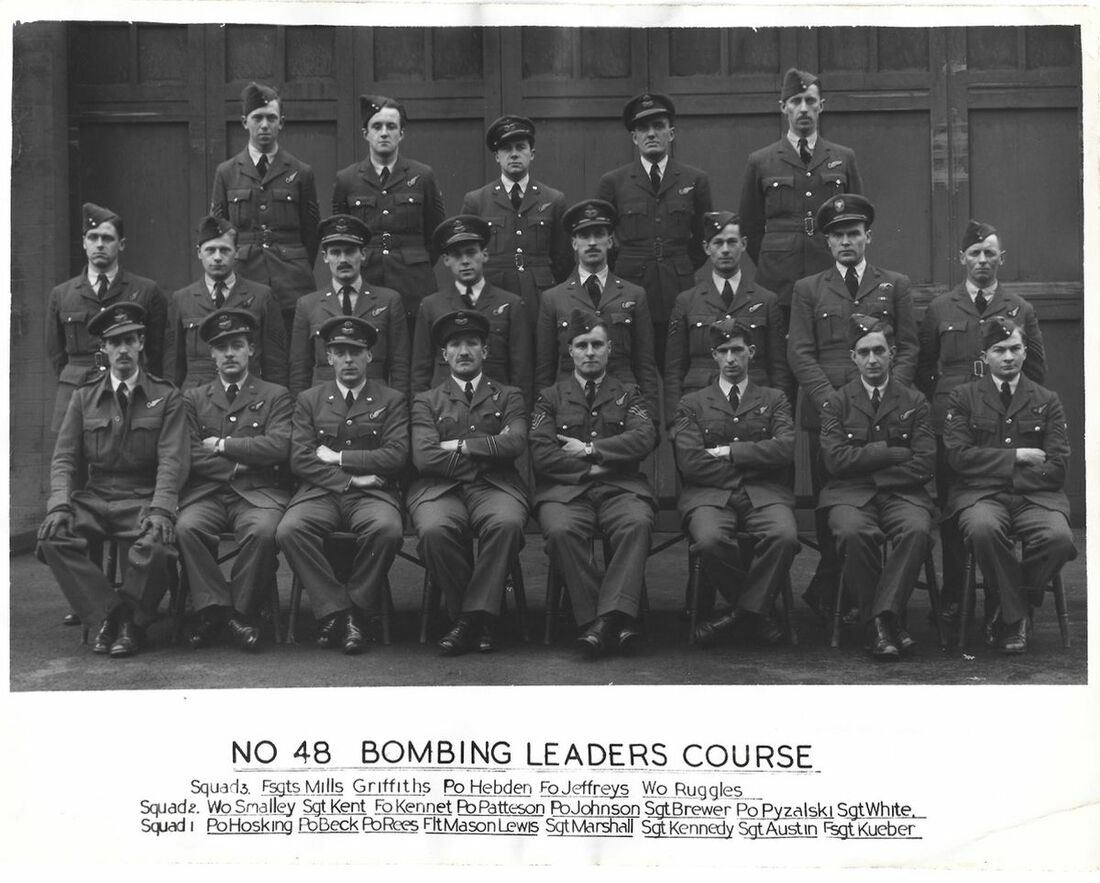

Following a richly-deserved rest over Christmas 1943, Johnson joined the Bombing Trials Unit at West Freugh in February 1944 and formed a good crew with Flight Lieutenant Broomfield. By the time Johnson was released in April 1947, he had some 1269hrs 10mins to his name across 13 different aircraft.

Returning to Blackpool, he became a Sales Manager of Sellers Fireplaces and introduced a popular line of fireplaces using marble imported from Italy. He eventually retired as a Director of the Company.

Johnson was a regular attendee of the Dambusters events in the years that followed and made many visits to Germany and Holland to the places which he had given such vital contributions to the Second World War. He died on 1 October 2002, aged 90.

Sold together with the following remarkable and complete original archive comprising:

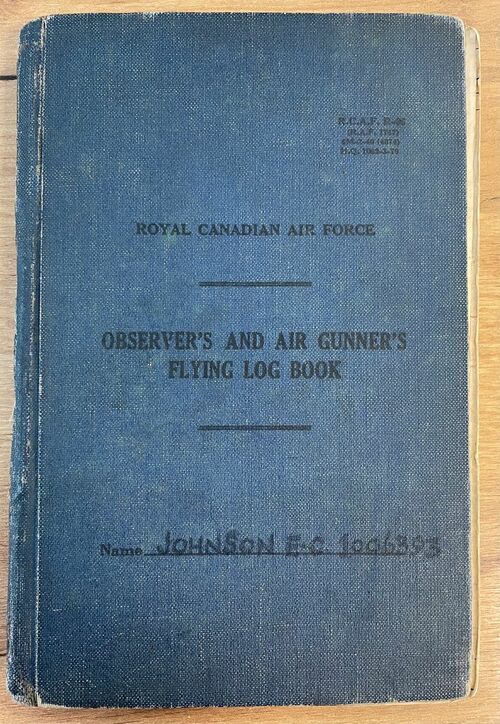

(i)

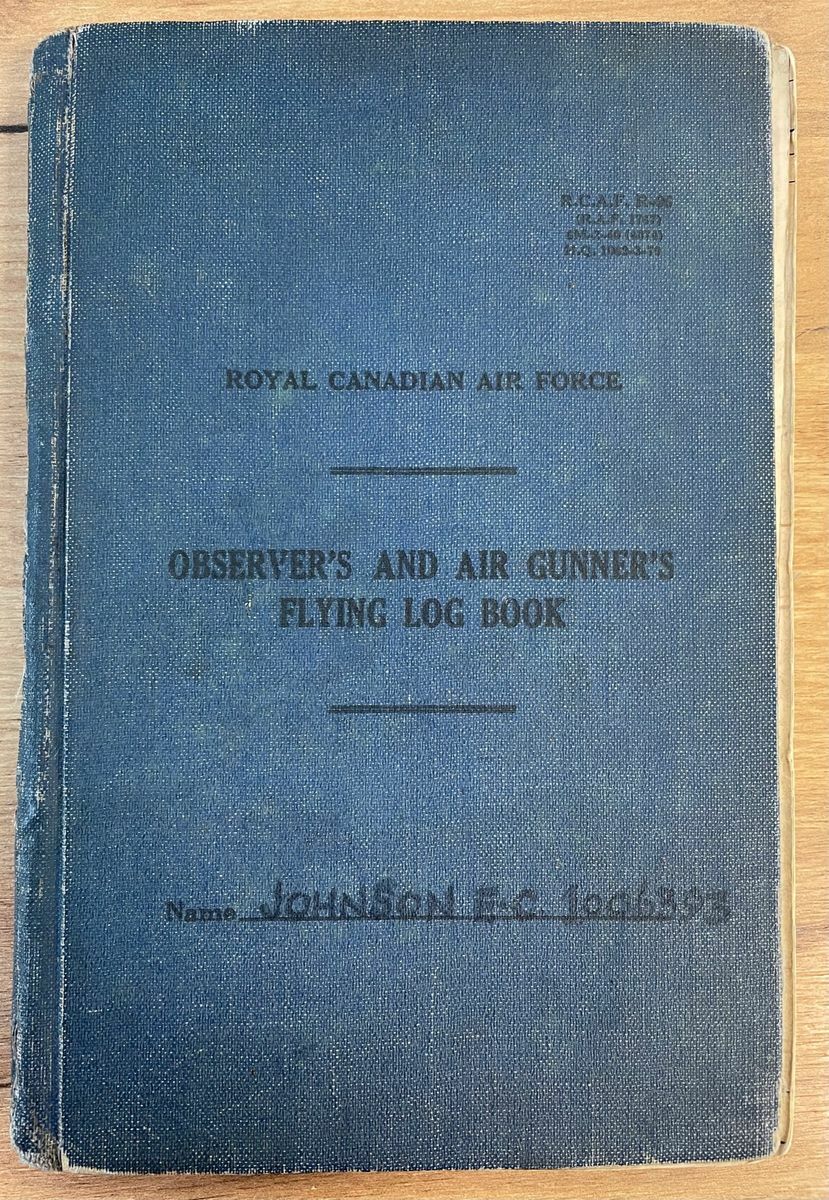

His Royal Canadian Air Force Observer's and Air Gunner's Flying Log Book, covering the dates 11 August 1941-17 April 1947.

(ii)

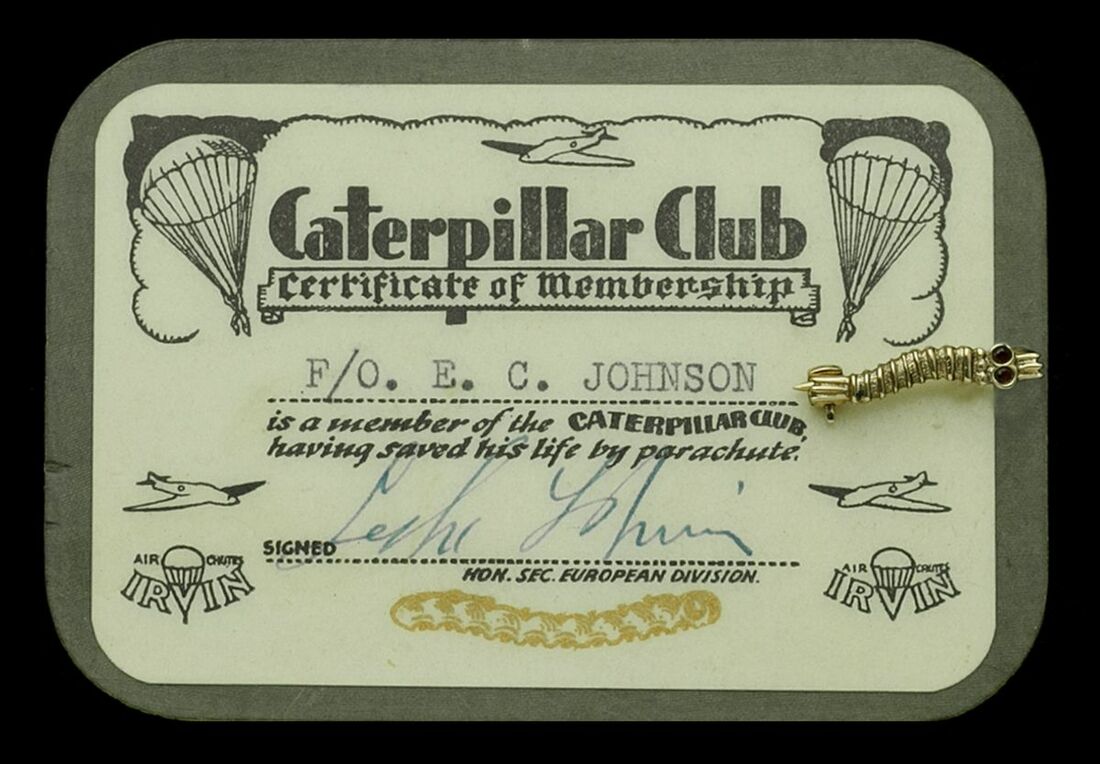

Caterpillar Club Badge, gold and 'ruby' eyes, the reverse officially engraved 'F/O. E. C. Johnson.', together with his Certificate of Membership card and Caterpillar Club Association (U.K.) North West Branch Membership card.

(iii)

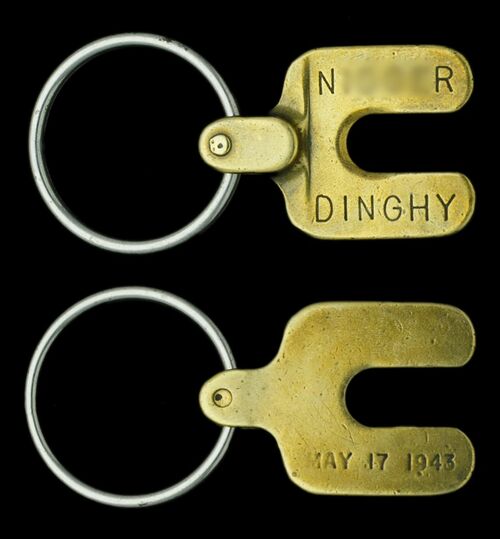

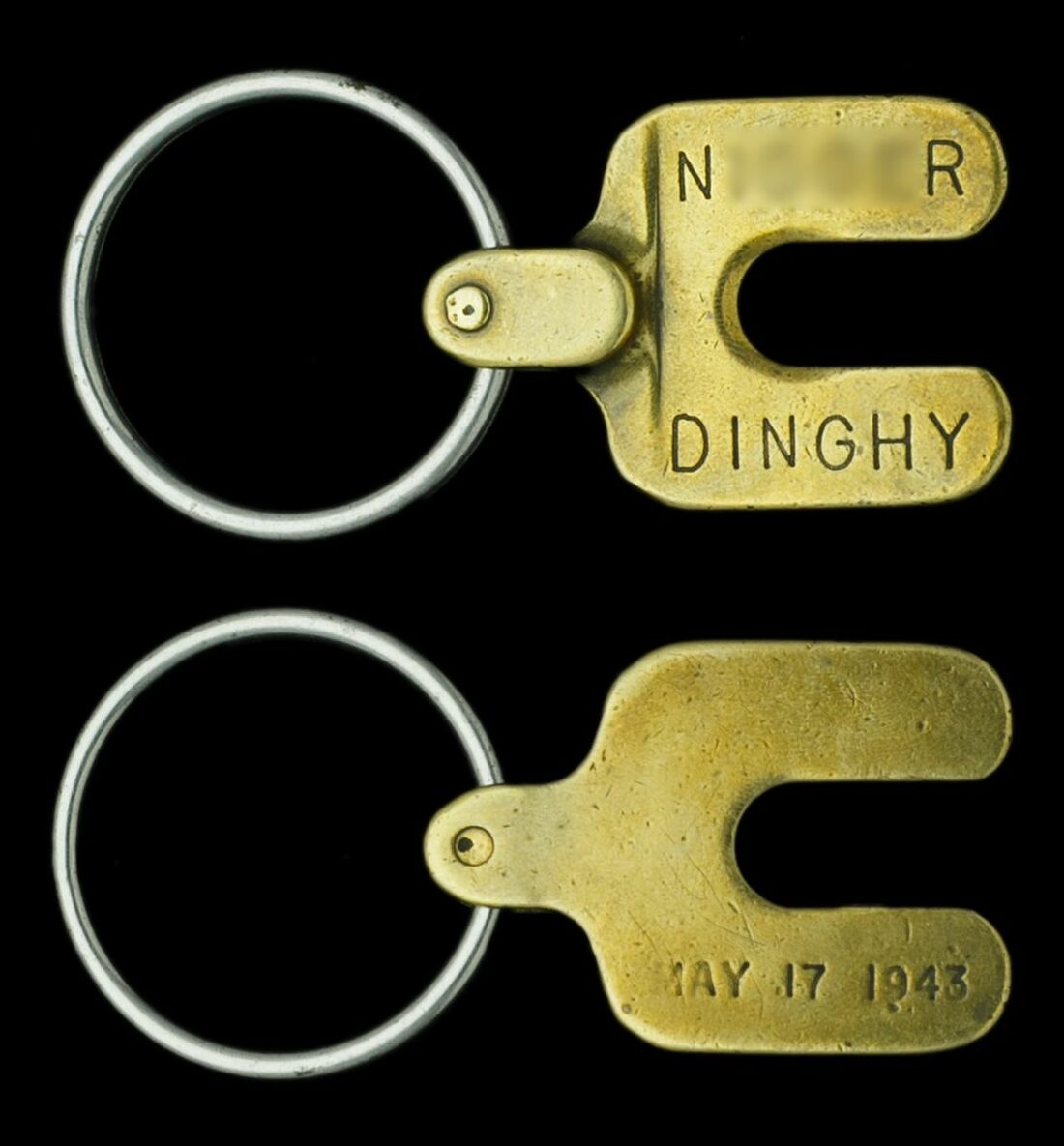

The original arming fork from the 'bouncing bomb' which breached the Eder Dam, brass, 45mm x 34mm, engraved 'N----R DINGHY', denoting the morse signals for the successful breach of the Mohne (the code being the name of Guy Gibson's dog) and the Eder (DINGHY), the reverse engraved 'MAY 17 1943', with split ring as carried as a key ring by the recipient for the remainder of his life, a remarkable relic of this legendary action. With a hand-written note from Johnson stating:

'This is a one off and could be very valuable. It is the 'arming fork' from the delayed action fuse in the Barnes Wallis bomb which breached the Eder Dam. Attached by wire to the aircraft body - it was recovered by the Bomb Aimer (me) on the return to base - the code names were put on later.'

(iv)

The Erasmus Medal, 50mm, bronze, in its case of issue, presented to Johnson as a Member of No. 617 Squadron in August 1985 (No. 14736) to commemorate the 40th Anniversary of the Liberation of Holland, together with the related issuance letters.

(v)

Royal Air Force Flying Clothing Card (Form 667B.) and National Registration Identity Card.

(vi)

Letter from Sir Barnes Wallis C.B.E., dated 20 July 1972, thanking Johnson for his letter and apologising he could not join him on a recent visit to Canada. He closes the letter:

'If ever you are in London, do let me know, as I would love to meet you and talk over old times.

Affectionally yours, Barnes Wallis'

(vii)

Two drilled core sections from the Mohne and Eder Dams, as presented to Johnson.

(viii)

Relics recovered from an inspection of the crash site of Lancaster-N for unexploded ammunition, which crashed on 16 September 1943, namely a cockpit lamp (AM Ref. No. 5c/366) and a rivet section.

(ix)

His No. 617 Squadron tie, upon which his Caterpillar Club Badge was proudly worn for many years.

For his miniature dress medals, please see Lot 342. For the medals of his father, who was killed in action in December 1914, please see Lot 92.

Subject to 5% tax on Hammer Price in addition to 20% VAT on Buyer’s Premium.

Sold for

£105,000

Starting price

£45000

Sale 23003 Notices

'Now further accompanied with additional original papers, including his copy of the film script for 'The Dambusters', with forwarding letter, two signed Programmes for the premiere evenings and also his written and typed account of his operational career, these last of an unpublished nature and a good primary account.'