Auction: 23003 - Orders, Decorations and Medals

Lot: 308

'In 1951 I was a Flight Lieutenant in the Air Ministry responsible for Navigator training. And one June morning Squadron Leader Martin came into the office. He said he'd just been to see the Vice Chief and been told that he was going to be put in charge of a small band of people to do some special flying. For security reasons he wasn't able to tell me what this flying was about.

He said, 'I've come to you. I'd like to nominate or find me a good navigator.'

Well, Micky was well known for his exploits in the War. So I realised this was going to be an interesting project.

So I said to Micky, 'I nominate myself.' I'd be silly if I didn't. And happily he accepted.'

Sanders on his joining Operation Ju-Jitsu, as recalled by Paul Lashmar in Spy Flights of the Cold War

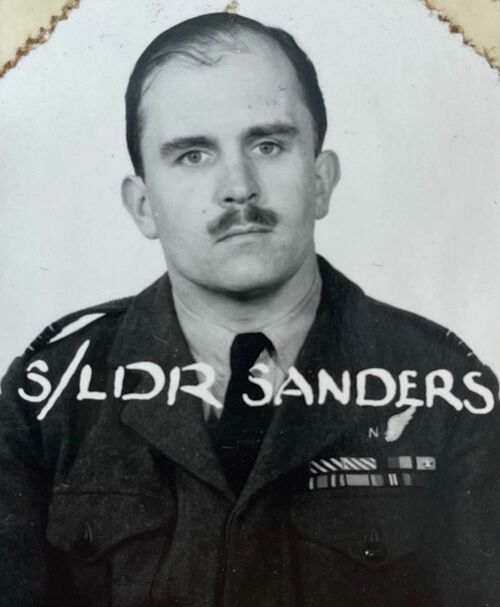

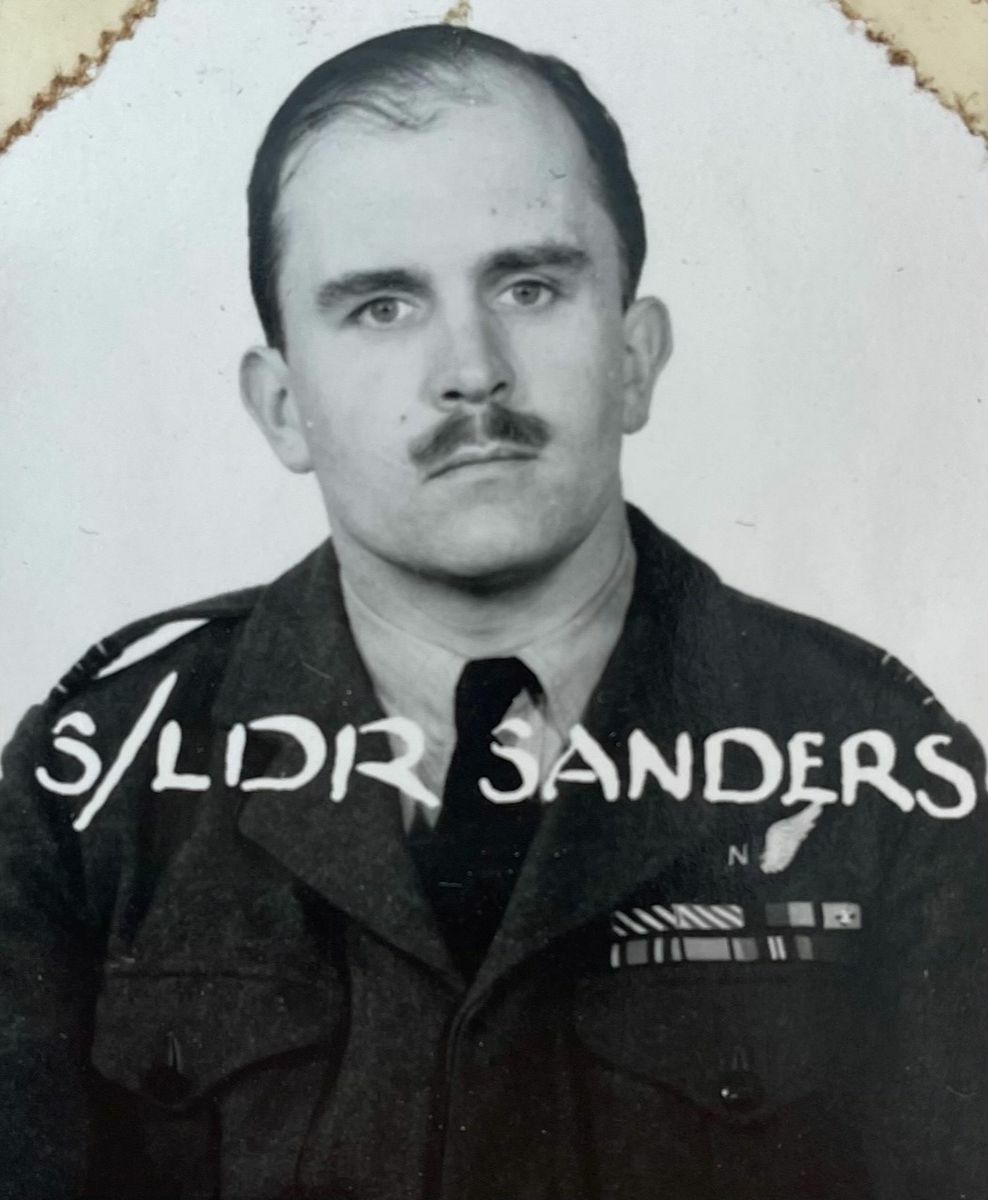

The important 1977 O.B.E., 1944 Bomber Command D.F.C., 'Operation Jiu-Jitsu' A.F.C. & Bar group of ten awarded to Wing Commander R. S. Sanders, Royal Air Force

Having cut his teeth on a full 34-Op tour over Europe, which saw him fly on at least four Ops to 'The Big City' - Berlin - and share in 'Big Week', his finest hours would come during the Top Secret flights over Russia during the Cold War, in collaboration with the United States

Sanders earned his immediate A.F.C. for their first flight deep into enemy territory in April 1952, and thence the Second Award Bar for good measure on the second foray in April 1954; these Missions were sanctioned and closely monitored by Winston Churchill himself

The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire, Military Division, Officer's (O.B.E.) breast Badge, silver-gilt, in its Royal Mint case of issue; Distinguished Flying Cross, G.VI.R., reverse officially dated '1944', with its case of issue; Air Force Cross, G.VI.R., the reverse officially dated '1953', with Second Award Bar, the reverse officially dated '1954'; 1939-45 Star, clasp, Bomber Command, this clasp with its case of issue, the base with label stating 'Wg Cdr R S Sanders 135043'; Air Crew Europe Star; Burma Star; Defence and War Medals 1939-45; General Service 1918-62, 1 clasp, S. E. Asia 1945-46 (Flt. Lt. R. S. Sanders. R.A.F.); France, Republic, Legion of Honour, breast Badge, by Arthus Bertrand, mounted court-style as worn apart from the first and last, good very fine (10)

O.B.E. London Gazette 31 December 1977. The original Recommendation, noted as 'Honours in Confidence', states:

'Wing Commander Rex Southern Sanders entered the Royal Air Force in April 1941.

For the last 5 years he has served in the Defence Operational Requirements Staff where his duties have included the examination and assessment of future equipment proposals and the provision of advice within the Central Staffs and to the Service Departments on Operational Requirement matters.

Sanders has acquired an outstanding depth of knowledge and understanding of a wide range of operational equipment topics which he has applied in a series of thorough and painstaking evaluations of successive complex and high cost projects.

The results he has achieved have been quite exceptional and have contributed significantly to the work of his Branch and to the benefit of the Services. Much of Sanders' success can be attributed to his undoubted intelligence, perception and imagination. However his achievements would not have been possible but for his sheer zeal and his willingness to work extremely long hours, often under considerable pressure, without thought for his personal interests and well beyond what could be reasonably interpreted as the normal call of duty. This selfless devotion has been all the more commendable in view of his approaching retirement.

Sanders outstanding abilities have earned much admiration from his colleagues of all three Services and he is a first class representative of the Royal Air Force. The Services have profited greatly from Sanders contribution, and his sustained, unflagging, efforts over an extensive period demand recognition. It is recommended most strongly that his outstanding services be recognised at this last opportunity prior to his retirement from the Service.'

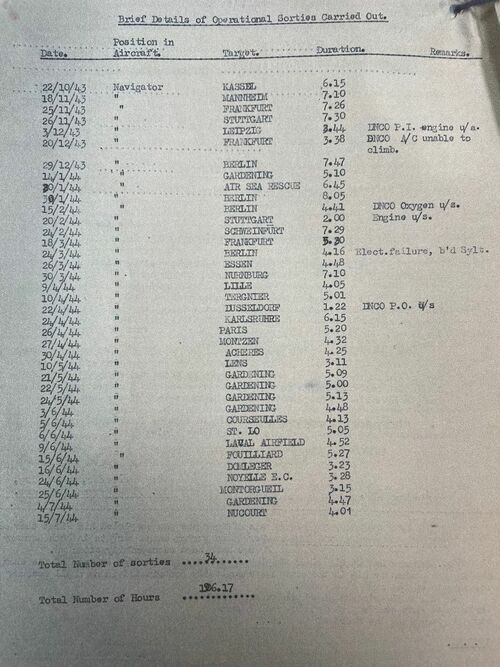

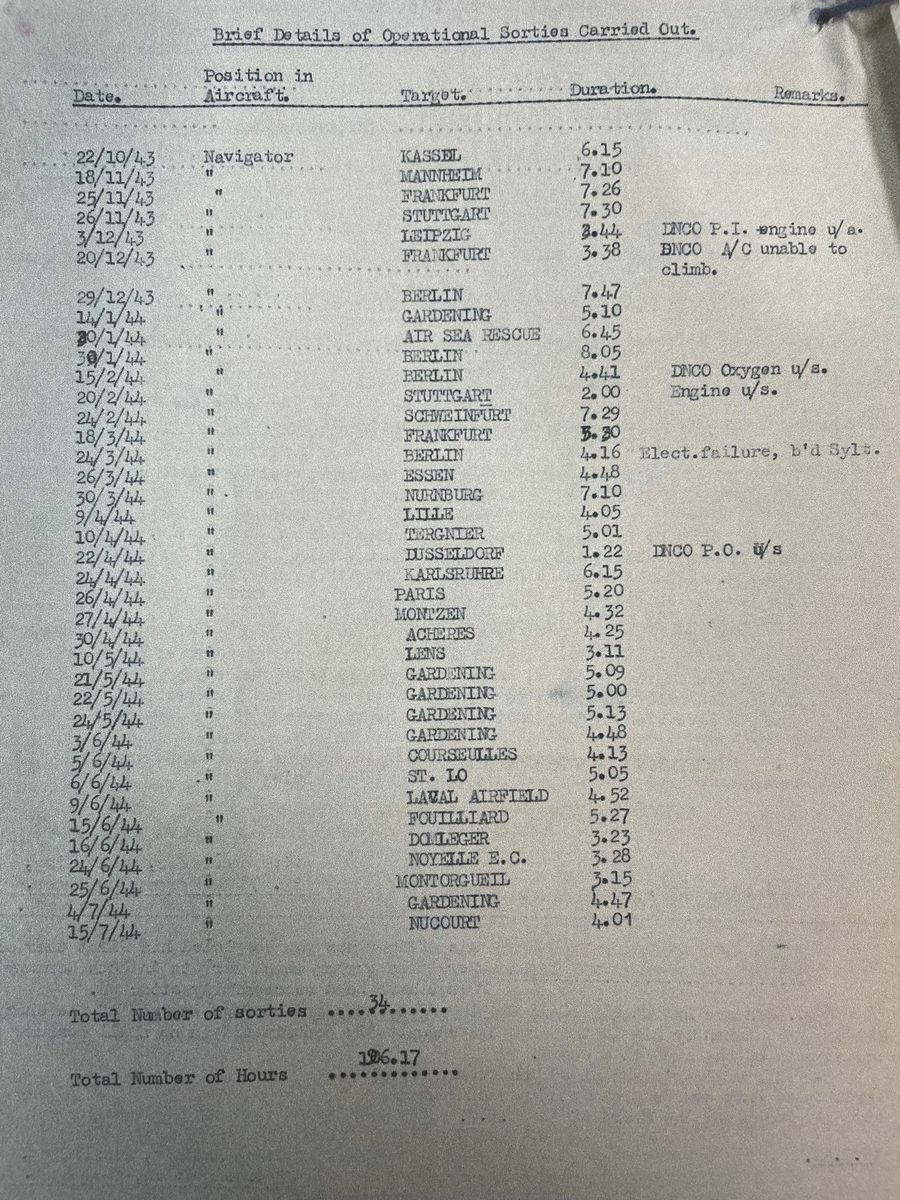

D.F.C. London Gazette 8 December 1944. The original Recommendation states:

'This Officer has completed his first operational tour consisting of 34 sorties, involving a total of 196 hours.

He has been outstandingly successful as a navigator, and has shown his ability on many raids against the most heavily defended targets. At all times he has shown the greatest coolness in face of the enemy, and his work on operations has been of an extremely high standard, as is proved by his night photographs.

He has done much to achieve the present standard of navigation on the Squadron, and has frequently acted as deputy Navigation Leader. His work in his section and his fine personal example have been an inspiration to the newer members of the Squadron.

For his outstanding devotion to duty he is most strongly recommended for the award of the Distinguished Flying Cross.'

A.F.C. London Gazette 1 January 1953.

Second Award Bar to A.F.C. London Gazette 10 June 1954.

A fine account of the life and times of Rex Southern Sanders was offered in his Daily Telegraph obituary, after his passing on 10 May 2017:

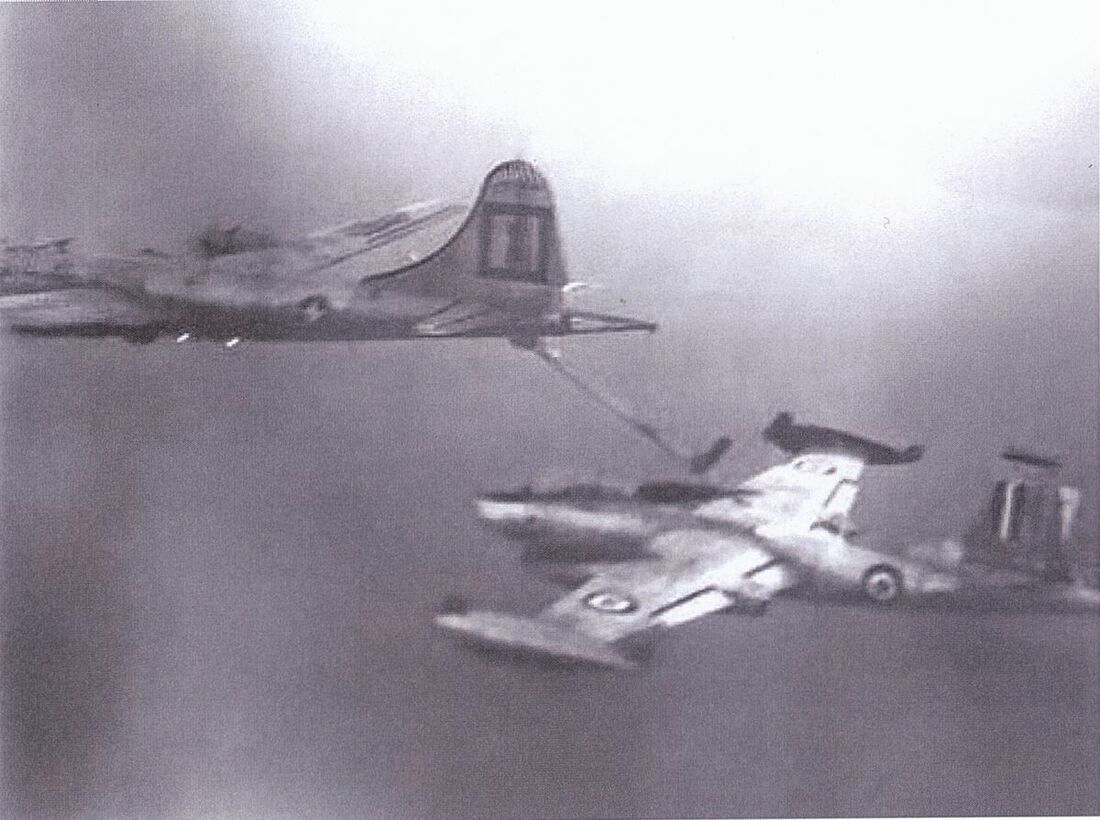

'Wing Commander Rex Sanders, who has died aged 94, was the lead navigator of a select nine-man RAF team that flew USAF reconnaissance aircraft on a series of top secret, and highly risky, spy flights deep into the Soviet Union in the early 1950s.

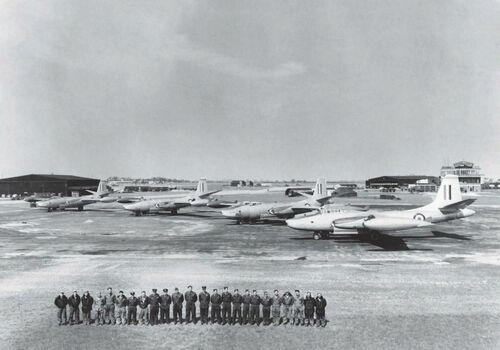

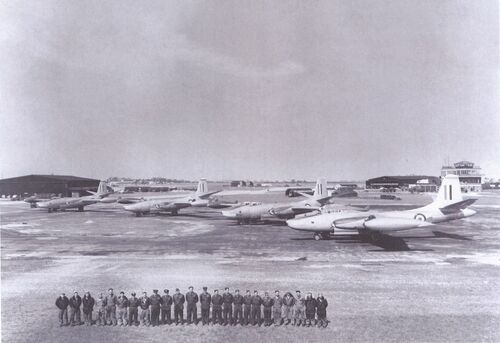

In August 1951, three RAF bomber crews flew to a USAF base in Louisiana to train on the North American RB-45C four-engine jet reconnaissance aircraft. The leader of the team was Squadron Leader John Crampton and Sanders was his navigator. The following February the crews were briefed on the operation code-named Ju-Jitsu.

After Crampton and Sanders had flown a practice flight – a high-speed, high-altitude sortie along the Berlin Air Corridor to test the Soviet reaction (there was none) – Winston Churchill, the prime minister, gave approval for the top-secret flights. Sanders recalled: “We went at full throttle … to try and stir things up. We were like ferrets going into a rabbit warren.”

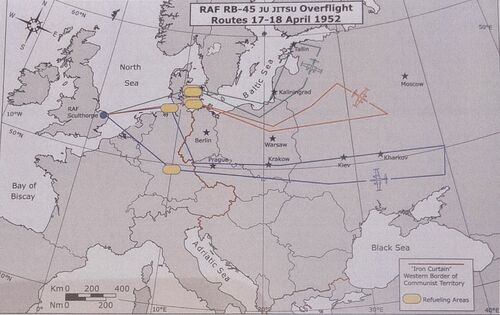

The three aircraft took off on April 17 1952 and headed for Denmark where they refuelled from airborne tankers. Crampton then turned south-east for Russia, flying at 36,000 ft. Electronic intelligence was gathered and photographs taken of the targets; the aircraft landed back at base after an uneventful 10-hour flight.

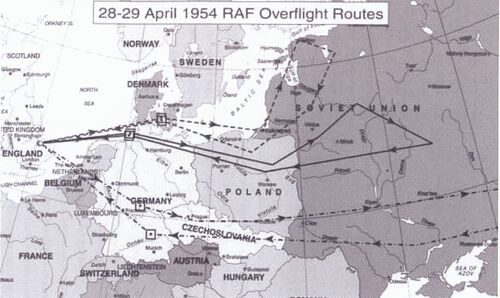

The three crews returned to normal duties, but the special unit was reformed in April 1954 for another series of flights. On the 28th, Crampton and Sanders headed for Kiev; the longest of the three flights. Sanders had just taken some photographs when the RB-45C came under anti-aircraft fire. Realising that his aircraft had been identified and was being tracked by ground radars, Crampton applied full power and turned west towards Germany, some 1,000 miles away.

Four RB-45Cs were flown to an RAF base in north Norfolk, where they were shorn of their USAF markings and repainted with RAF roundels (one aircraft was to act as a spare).

General Vladimir Abramov, commander for the Kiev region, revealed in later years that he had ordered MiG fighter pilots to try and ram the spy aircraft but they were unable to reach 36,000 ft to intercept the RB-45C.

This highly clandestine Cold War episode remained a closely guarded secret until 1994 when the BBC and The Daily Telegraph disclosed some details. Sanders was among retired RAF personnel interviewed on the BBC’s Timewatch programme a few years later. When asked for his views, he responded: “I think it was an amazing decision and very much reflects the character of Churchill. Had we gone down, there would have been quite a furore.”

The RAF and USAF commanders considered the flights valuable and Crampton and his crews were decorated, Sanders receiving the AFC, adding a Bar for the second flight.

The eldest of five children of a civil engineer, Rex Southern Sanders was born on December 14 1922 at Bridlington but brought up in Wandsworth, south London, where he attended the Central School. No great academic, Rex was a good sportsman and he ended up as the swimming captain. He left school at 15 and took a job as a draughtsman; he was working at an ordnance factory at Wrexham when war broke out.

There was no history of aviation in his family, but he was fired by dreams of becoming a Spitfire pilot, and in April 1941 he enlisted in the RAF Volunteer Reserve, training as a navigator in Canada under the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan.

On his return to Britain he discovered that his family had been evacuated from their home after it had suffered in the bombing of London. He completed a bomber training course and in October 1943 joined No 78 Squadron based in Yorkshire, operating the four-engine Halifax.

Within a few weeks of his arrival, Bomber Command embarked on its most intensive period of operations with the start of what became known as the Battle of Berlin. Sanders made a number of sorties to the “Big City”, which he described as “quite difficult”.

Nevertheless, before the first operation he had told the crew he was happy to bomb Berlin because his parents had been bombed out of their home in London. “We didn’t have any reservations,” he remembered. He also attacked other major cities before the bombers were switched to targets in France in preparation for the D-Day landings.

On the night of June 5 1944 he attacked gun batteries on the Channel coast, unaware that the air and sea invasion was about to begin. He recalled: “Coming back my radar showed the Channel chock-a-block with ships. I told the crew: ‘This is it.’ ”

Sanders was rested after completing 33 operations. In 11 months his crew were only the third in their squadron to complete a full tour of duty. More than half had been lost. He was awarded the DFC.

Having been a religious person before the war, by the end of it Sanders had lost his faith, and in later years he reflected: “When I look back on it now it weighs very heavily on me … I feel badly about dropping bombs on civilians but it just had to be I suppose. I’ve closed my mind to so much.”

He went to India in April 1945 but the war against Japan came to an end before he flew on operations.

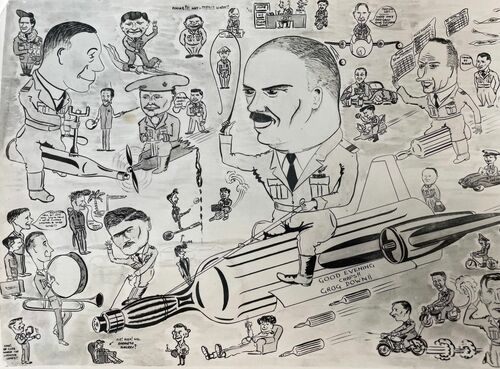

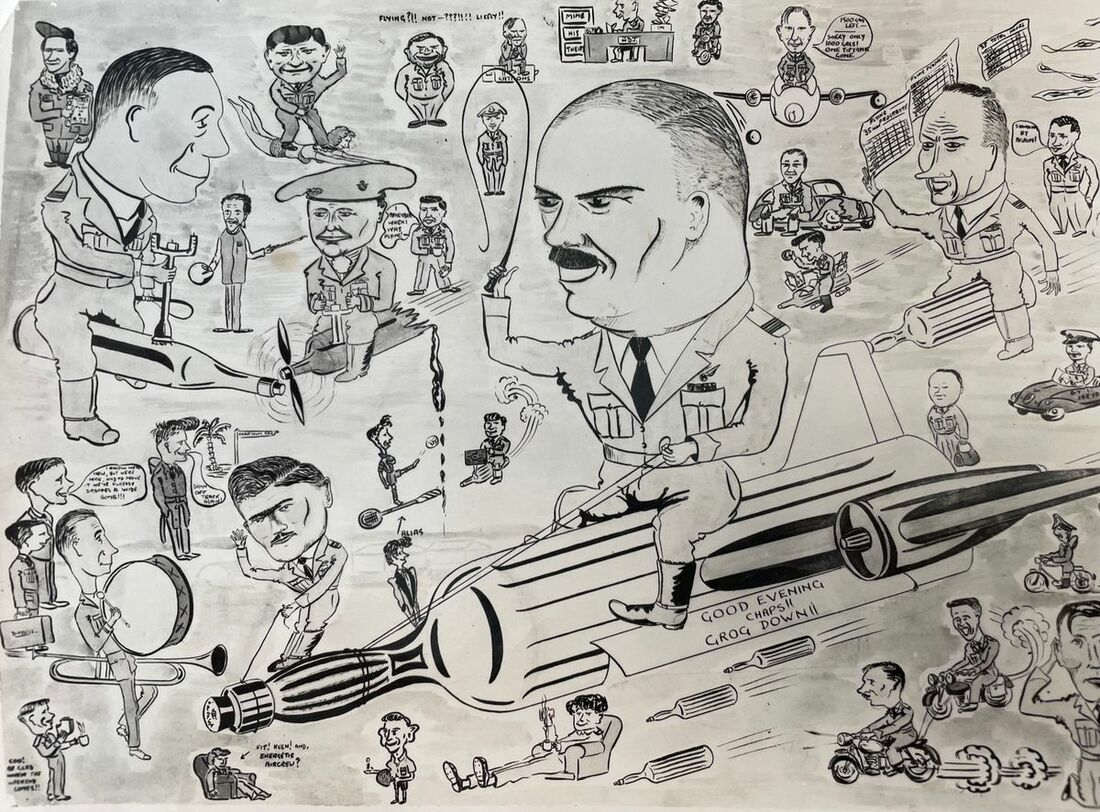

On his return to the UK he specialised in navigation before his clandestine flights and in August 1953 he assumed command of No 35 Squadron flying the US-built B-29 Washington, before the squadron converted to the Canberra twin-engined jet bomber.

After completing the RAF Flying College Course, when he made a hazardous flight to the North Pole in a Canberra, Sanders specialised in guided weapons before he served in charge of operations on a Thor Intercontinental Ballistic Missile Site in Norfolk.

After two years as the air adviser to the Pakistan Air Force he assumed command of RAF Aberporth on the Welsh coast from where air defence missiles, including the Bloodhound surface-to-air guided missile, were tested. His final appointment was a five-year tour in the MD Operational Requirements Directorate.

His secret work resulted in his being appointed OBE.

He retired in December 1977, after which he took up painting and lived quietly in Norfolk before eventually settling on the west Wales coast.

He had no children himself but became something of a mentor to his autistic step-grandson Tommy, patiently encouraging the boy in his considerable practical skills. Rex Sanders married his first wife Gloria in 1948; she died in 1986. His second wife, Rhiannon, survives him with a stepson.'

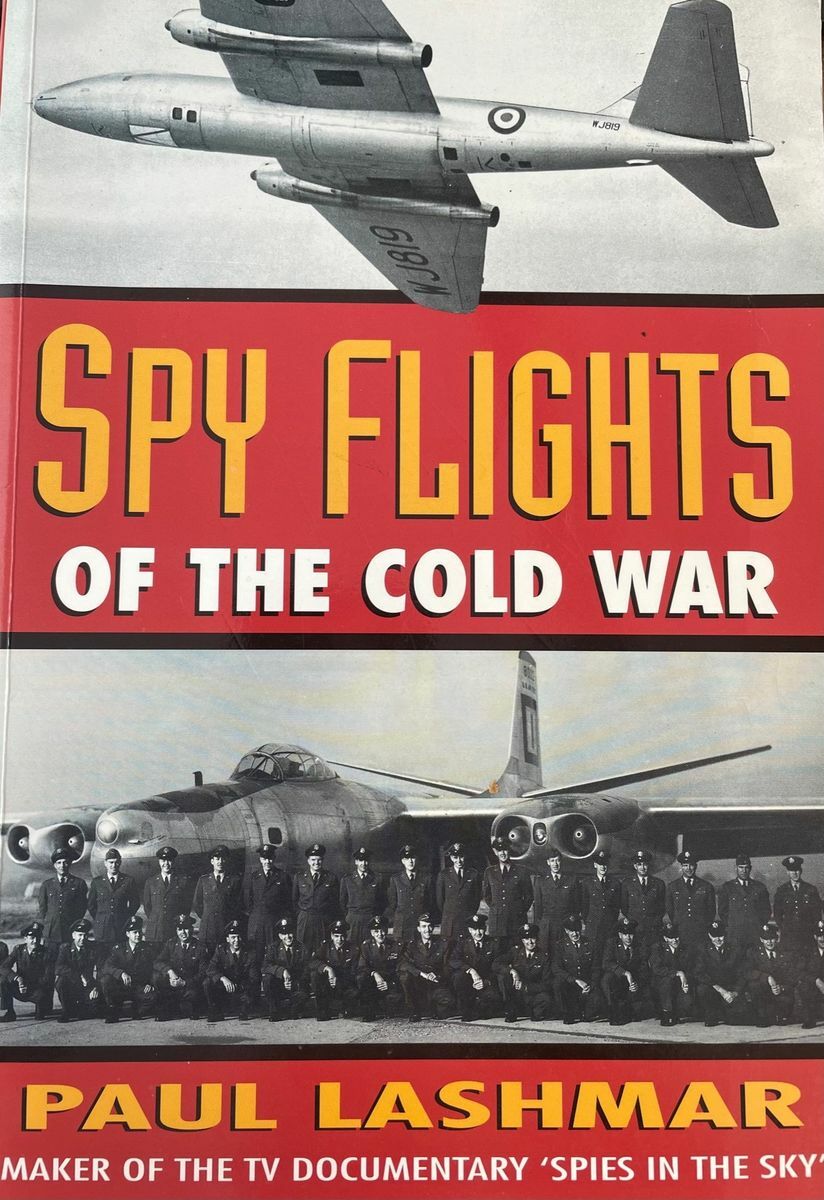

Details of his remarkable exploits during the Cold War were covered by Paul Lashmar in Spy Flights of the Cold War and also by Key Aero:

'In early 1952, preparations were well advanced for an audacious Cold War operation, as Sqn Ldr John Crampton and his colleagues from the RAF Special Duty Flight got ready to fly their US-loaned North American RB-45Cs on deep penetration missions over the Soviet Union. Highly secret at the time, Operation ‘Jiu Jitsu’ can today be seen as the start of a new period in aerial reconnaissance.

Three years after the detonation of the Soviet Union’s first atomic bomb in August 1949, US Air Force Strategic Air Command and RAF Bomber Command were fearful of a pre-emptive nuclear strike. Both wanted detailed target intelligence on the likely locations from which a Soviet nuclear offensive might be launched. The British priority was identifying Russian bomber bases, as these posed the most immediate threat to the United Kingdom. Also, it would be British airfields from which SAC was to mount any nuclear offensive against the USSR.

Lacking adequate targeting data, SAC’s 1951 war plan envisaged it being necessary to quickly deploy reconnaissance aircraft to Europe, to overfly likely Soviet nuclear bomber bases within 72 hours of hostilities commencing, probably incurring heavy losses. The radar scope imagery they collected would be used by SAC’s heavy bomber wings to launch nuclear attacks on those bases. However, if they assembled sufficient targeting data before hostilities, they would be in a better position to mount a retaliatory or pre-emptive strike.

To collect the target imagery in peacetime required making highly provocative overflights deep into Soviet territory. As SAC commander Gen Curtis LeMay said, the task required a “freedom of initiative not likely to be provided a military commander in a democracy”. The existing US shallow-penetration flight programme was inadequate and had already incurred significant losses. While the USAF had the resources to mount these missions, the RAF did not. The shooting-down of US Navy Consolidated PB4Y-2 Turbulent Turtle in April 1950, while engaged in a Baltic reconnaissance mission, and the approaching 1952 US presidential election have been cited as reasons why the Americans wanted the British to make the overflights. Some British policymakers viewed flying these sorties as a means of contributing to the Anglo-American intelligence collection effort. They would also provide invaluable intelligence ready for the service entry of the first RAF ‘V-bombers’.

Discussions during 1951 led to USAF chief of staff Gen Hoyt Vandenberg agreeing to train RAF personnel for flying high-level — around 40,000ft — reconnaissance operations on the RB-45C, to prepare them for possible missions over the USSR. Ahead of a firm political agreement to mount these deep-penetration overflights, HQ Bomber Command began searching for RAF crews to fly the RB-45C, a much-improved reconnaissance version of the B-45A Tornado bomber, which was just entering USAF service in early 1951. At the time it was the only aircraft suitable to undertake such missions.

RAF aircrew selection was headed by Sqn Ldr Harold ‘Mick’ Martin of Ruhr dams raid fame. He was personally chosen for the task by the Vice-Chief of the Air Staff (VCAS), ACM Sir Ralph Cochrane, who had himself been commander of Operation ‘Chastise’ as Air Officer Commanding No 3 Group, Bomber Command in 1943. Martin selected then-Flt Lt Rex Sanders, posted to the Air Ministry, to be his navigator. However, Martin had to withdraw when he failed a high-altitude depressurisation test, unable to meet the necessarily stringent medical requirements.

In July 1951, Sqn Ldr John Crampton was the CO of No 97 Squadron on the Avro Lincoln when he was called to HQ Bomber Command. As he said, “the Commander in Chief of Bomber Command sent for me and said I was to assume command of an RAF Special Duty Flight, under conditions of the utmost secrecy. The secret flight would be equipped with the North American RB-45C jet reconnaissance aeroplanes and the RAF crews would proceed almost immediately to the US to begin sixty days training.”

The SDF was to consist of three aircraft, each with a three-man crew comprising a pilot/aircraft commander, co-pilot/flight engineer and a photo-navigator. Within the mixed officer and NCO crews, Cochrane wanted at least one pilot with a photo-reconnaissance background and another to be a qualified flying instructor. He sought two navigators with experience on the B-29’s AN/APQ-13 radar or the British H2S MkIV, with two flight engineers being drawn from RAF B-29 Washington squadrons.

The aircrew assembled at RAF Sculthorpe and flew on a SAC Boeing C-97 Stratofreighter to Louisiana on 3 August 1951. After 10 days of conversion training with the B-45A at Barksdale AFB, they transferred to Langley AFB, Virginia for their introduction to the more advanced RB-45C. On 2 September they moved again, this time to join the 91st Strategic Reconnaissance Wing’s 323rd Strategic Reconnaissance Squadron at Lockbourne AFB, Ohio. At that time the wing’s other two squadrons were on rotation, one to Sculthorpe and the other to Yokota AB in Japan. During training, one RAF pilot made a very heavy landing at Lockbourne. He was summoned before LeMay and sent home to be replaced by another RAF exchange pilot, already flying the B-45. Crampton and his colleagues returned to the UK in December 1951 to form an additional flight within the resident 91st SRW’s RB-45C detachment at Sculthorpe. Tanker support was provided by six KB-29Ps of the wing’s own 91st Air Refuelling Squadron, also at Sculthorpe.

Mounting deep-penetration flights beyond the Iron Curtain required the highest level of political agreement. Winston Churchill had again become Prime Minister in the autumn of 1951 and was anxious to see President Harry Truman. In their early January 1952 meetings, part of their agenda was the discussion of “US strategic air plans”, which included American nuclear-capable bomber basing in the UK. In the run-up to his meeting with Truman, ACM Cochrane had met with Lord Cherwell, the PM’s close personal adviser, to discuss overflights and brief Churchill on the necessity for peacetime reconnaissance to make US wartime strike plans viable. As VCAS from 1950 and chairman of the HEROD (High Explosive Research Operational Distribution) Committee, Cochrane was instrumental in developing all aspects of emerging RAF nuclear policy in conjunction with the service’s most senior officers responsible for these weapons.

A rather overlooked event in the development of close aerial intelligence co-operation between the RAF and USAF is a key meeting between Cochrane and LeMay. The month after Churchill saw Truman, around 18 February 1952 Cochrane and Sir Kenneth Strong, head of the UK’s Joint Intelligence Board, visited LeMay at SAC headquarters at Offutt AFB, Nebraska. Their task was “to find out about American nuclear capability, the provision made for targets of special interest to Britain, and in more general terms other target systems the Americans were considering”. A four-page February 1952 paper entitled ‘The Counter-Offensive Against the Soviet Long Range Bomber Force’ was marked for the attention of the PM, and most likely authored by Cochrane. It explained the case for the RAF to undertake what was soon known as Operation ‘Jiu Jitsu’.

In this forward-looking document, Cochrane demonstrated a detailed understanding of contemporary US nuclear policy. It also recognised that until the RAF’s Valiants became operational, which was still some years away, only the Americans possessed a long-range nuclear strike capability. Before then Britain, and the RAF airfields housing the SAC strike force, would be vulnerable to a pre-emptive Soviet attack. If it were to stand any reasonable chance of success, any offensive US nuclear strike against Soviet bomber bases would almost certainly have to be mounted at night to reduce the likely heavy casualties among its aircraft and crews.

To be adequately prepared for that eventuality, it was necessary to collect radar reconnaissance imagery in peacetime. The best time of year to do this was assessed as being each April and November.

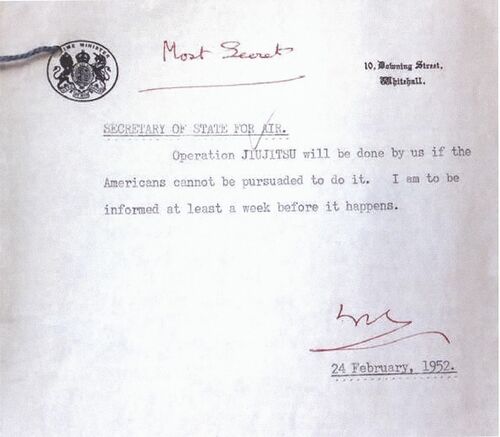

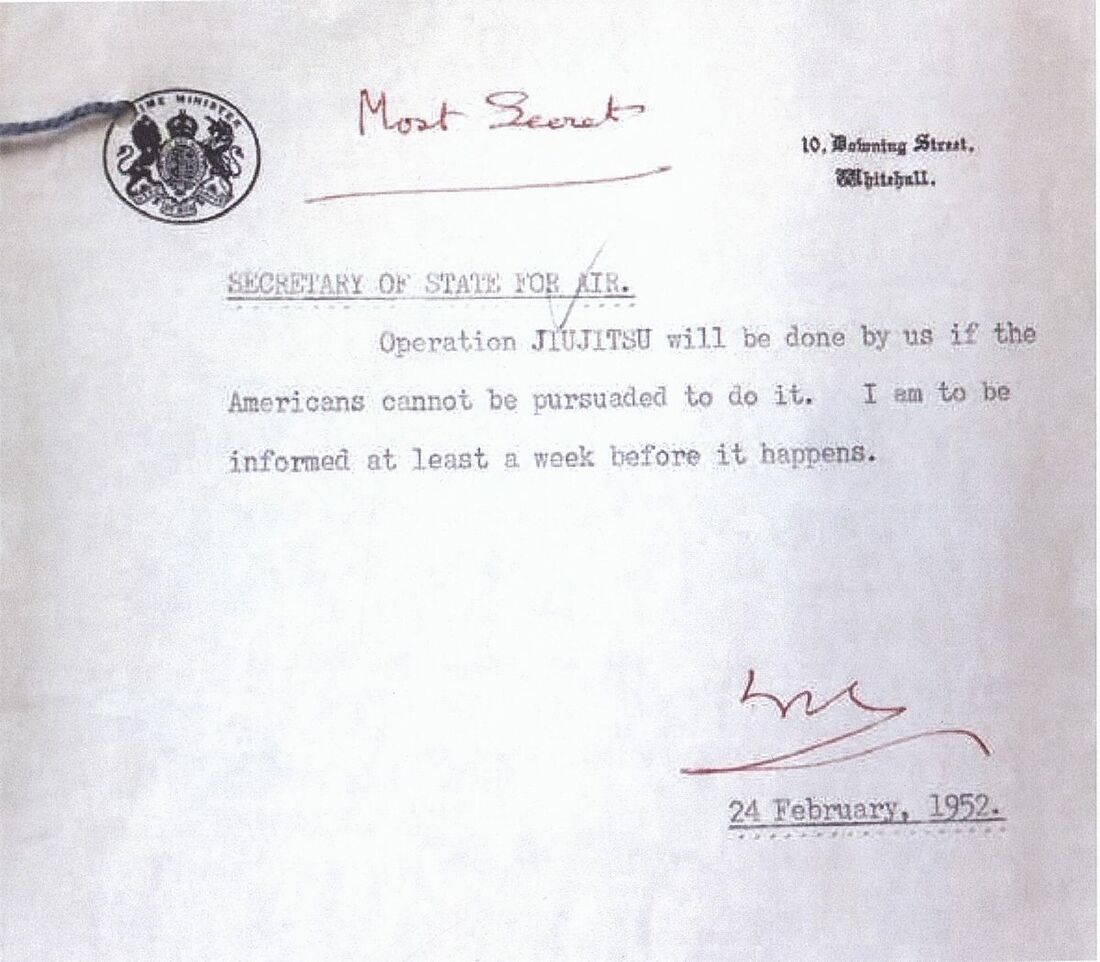

Churchill’s seemingly reluctant approval of Operation ‘Jiu Jitsu’, in the absence of US preparedness to do so, was given in a brief minute of 24 February 1952. It requested that he be notified a week in advance of the planned mission. In late February, Crampton was called to HQ Bomber Command at High Wycombe with Rex Sanders. Crampton recalled, “This was the moment of truth and I confess to some apprehension when the charts were unrolled, to show three separate tracks from Sculthorpe to the Baltic states, the Moscow area and central southern Russia”. He was told, “The deal was for the three routes to be flown simultaneously at night, departing Sculthorpe in rapid succession to rendezvous with the tankers north of Denmark. After top up, we were to climb at maximum continuous power, at Mach 0.68, to the highest altitude the night time temperature would allow… We were to fly without navigation lights and in radio silence.

“It was a relief to finally know what was expected of us, although I felt some concern at the thought of briefing my crews who, it must be remembered, were not volunteers”. His concerns appear to have been well-founded as one pilot, who had probably deduced what all their special training was really about, wanted no part in the operation and returned to his unit. Fortunately, an ideal replacement was found in Flt Lt ‘Bill’ Blair, an existing RAF exchange pilot with the 91st SRW. He had already flown a TDY (temporary duty) period at Sculthorpe from August-October 1951 and was quickly sent back to Norfolk from the US in order to join the SDF.

It was during a visit to Sculthorpe by the AOC-in-C Bomber Command, ACM Sir Hugh Lloyd, on 17 March 1952 that Crampton was fully briefed on the mission details. He was told that four aircraft were soon to arrive at Sculthorpe to equip the SDF. This would be done as part of a regular 91st SRW aircraft rotation. They duly landed on 20 March. Lt Col Marion ‘Hack’ Mixon, the 323rd SRS commanding officer, headed the detachment. Responsible for four 323rd SRS crews, six from the 91st ARS and Crampton’s SDF, he became a key figure in successfully enabling SDF operations. Four RB-45Cs were allocated to the flight: three mission aircraft and a spare. Mixon oversaw the temporary transfer of serials 48-019, 48-034, 48-036 and 48-042 to the RAF on 5 April 1952. Their USAF markings were removed and replaced with RAF ones — two of the RB-45Cs being repainted at nearby West Raynham — although none were allocated British serials.

With only a small number of nuclear weapons in the US stockpile, successful delivery was essential. Europe’s weather conditions made an accurate night and all-weather blind bombing capability vital. This could only be built around radar scope imagery, a technology still in its formative stages. During World War Two, one of the greatest problems for blind bombing was the difficulty operators faced in accurately interpreting their H2S displays. To be successful, bomb aiming required good-quality radar scope imagery of ground features approaching the target.

SAC had already begun its Radar Production Program to collect radar imagery on flights all over western Europe. On board RB-45C radar reconnaissance missions, a fixed mount 35mm camera took a photo on each sweep of the radar screen. Difficult to interpret, the imagery was developed and handled by a very small team of specialists. Its eventual value to operational crews would depend on the settings used by the reconnaissance aircraft’s AN/ APQ-24 radar.

While the USAF had undertaken considerable research and testing using standardised equipment settings, the British had exercised a more individual, flexible approach, led by the RAF’s Radar Reconnaissance Flight in the early 1950s. Initially based at Benson, the RRF moved to Upwood in March 1952 and later to Wyton. This little known unit was at the forefront of experimentation and developing advanced techniques for handling radar scope photography and its later operational application. Its work also included the development of systems and methodologies ready for the ‘V-bombers’. The RRF came up with techniques to ensure the successful and consistent processing of this imagery, known as ‘Peptone’. In preparation for these special flights American and British RRF personnel made a considerable effort to adjust the AN/APQ-24 radar on the RB-45Cs, so as to extract the best possible performance from it.

Rarely mentioned are Rex Sanders’ recollections of the April 1952 operation, which he provided in a 1993 interview with Paul Lashmar. Sanders explained some of the problems of radar scope photography at the time. “For all weather blind bombing you have to be able to recognise the radar picture of your target and there was quite a bit of unpredictability in how a target can appear on a radar scope. You could roughly recognise towns and cities, but the problem was being able to pick out particular features like a factory or an airfield. So you take these pictures and blow them up in a lab and you identify the radar responses from individual features. From that, you could train your crews in the recognition of specific targets.”

The USAF had airlifted a radar trainer to Sculthorpe in a C-97 transport. “[It was] built on a glass plate on which all sorts of materials, metal, dust and so on were placed to simulate the radar responses from a real target. When you had radar reconnaissance photographs to compare you could then reproduce a very accurate simulation. The bomber crews could then practice and that was how you would get accurate bombing.”

For the overflights, Sanders explained, “I wasn’t told what the actual targets were. I was given points to fly to and carry out simulated bombing runs on these points, [necessary] because as you got closer the radar picture changed. That would give the intelligence [people] the information they needed to reproduce it on a simulator for a bomber crew.”

Before the main operation, the British suggested a preliminary mission should be flown to test Soviet responses. As John Crampton said, it was agreed it should be carried out by “send[ing] one or two aircraft to go in a few miles only, and we would monitor the Russian reaction.”

Crampton did this with Sanders and Flt Sgt Gordon Acklam on 21 March 1952. However, this was much more than a shallow penetration. After the hasty application of RAF markings to an RB-45C, they departed at 19.15hrs, their route taking them to Hamburg and on into East Germany. Entering GDR airspace at 36,000ft, they headed over Parchim, Werneuchen, Finsterwalde, Merseburg and Eisenach. Crossing back into the west, the aircraft proceeded via Frankfurt and The Hague, landing back at Sculthorpe three hours 25 minutes later. Crampton said they were over “the Soviet zone of Eastern Germany for about an hour or so while our intelligence people monitored radio and radar activity”. With no major air defence response detected, it was judged that the crews were ready for a ‘live’ mission.

After the successful test flight, and with the routes now known, training became more sharply focused. The British crews began intensive flying, using mission profiles reflecting those required for the upcoming operation. There was a great deal of refuelling practice with the KB-29Ps. Following dress rehearsal missions, a final briefing was held at HQ Bomber Command on 16 April that involved ACM Lloyd.

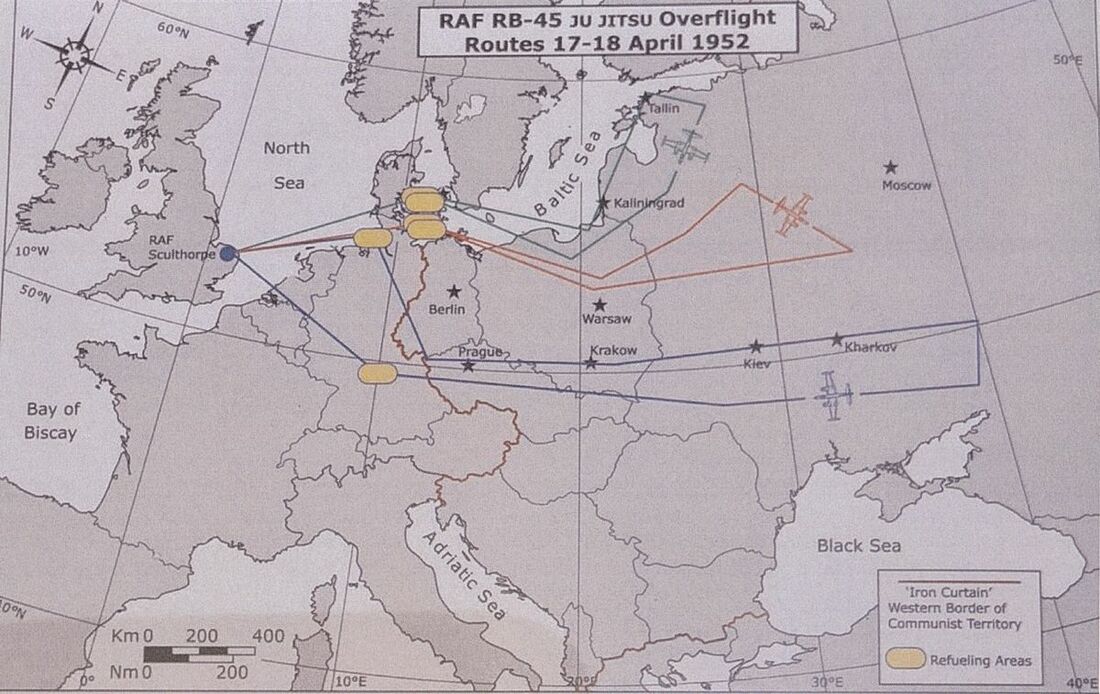

The three RB-45Cs left Sculthorpe on the late afternoon of 17 April and headed towards the Skagerrak, at the entrance to the Baltic Sea. Their spare aircraft had already gone unserviceable earlier that day and failed a later air test. With no room for further unserviceability, they needed to rendezvous with their tankers over Denmark and Germany just before dark, in radio silence. According to John Crampton, “We picked up our tankers, took on every pound of fuel we could, broke away, doused all the lights and headed south over the Baltic Sea into the black night.”

They split up to fly their three individual routes, an action intended to confuse Soviet air defences. In terms of the danger the aircraft faced, Rex Sanders recalled, “[Bomber Command] were relying on surprise as much as anything for our safety and I think they achieved it. We were not shot down, not even shot at.”

Blair, Flt Lt John Hill and Acklam flew the shortest route of some 2,500 miles, just over 1,000 miles of it above hostile territory. It was the most northerly route, covering targets in the Baltic republics and northern Poland. They made landfall at the eastern end of the Baltic near Kaliningrad, and turned northeast towards Tallinn on the Gulf of Finland prior to heading inland again. Completing their mission, Blair had to divert to Manston because of low cloud at Sculthorpe. They returned to Norfolk the following day.

The central route was flown by Sqn Ldr Gordon Cremer with Flt Sgts Don Greenslade and Bob Anstee. It took them across north-central Poland and into Belarus, where there was a major concentration of Soviet bomber bases relatively close to Minsk. They headed eastwards to Orel, about 180nm south of Moscow, where Anstee could see the glow from the Soviet capital on the night horizon. They returned via Poland following a similar route to their outbound flight. Experiencing engine problems, attributed to an iced-up fuel filter, Cremer headed to their agreed diversion airfield at Kastrup in Denmark. They later departed for home but were also foiled by the Sculthorpe weather, being forced to divert to Prestwick.

The more than 3,000-mile flight on the southern route was the longest, undertaken by Crampton, Sanders and Flt Sgt William Lindsay. It also reached furthest into the Soviet interior. They had taken off an hour before the other two missions. An outbound refuelling took place near Hamburg, from where they headed towards southern Germany, then across Czechoslovakia into Ukraine, beyond Kiev and close to Rostov-on-Don before making for home.

Rex Sanders said, “We just flew into the black. We cruised at .72 Mach — about 450kt, fully loaded with fuel. We started at about 31,000ft and finished at 37-38,000ft”. This was a consequence of the fuel load lightening. “Navigation was tricky, but the radar was very good. As long as the radar worked you knew where you were. It was difficult in that for reconnaissance, you have to play around with the radar settings to optimise it, so I was fiddling around like mad, but you knew where you were all the time.

It wasn’t a great feat of navigation. I was a bit of a one-man band because I had to navigate and do the reconnaissance as well.”

Sanders continued, “While we were doing our radar reconnaissance, all the other intelligence services were listening in and this is where ‘Jiu Jitsu’ became a large-scale operation. At our briefing, we were told that once the date was fixed we could not change it, because of everyone else who was involved. In that way, it was a very brittle operation, because of its complexity. The signals intelligence was as important to HQ Bomber Command as the radar photography.”

“My most abiding memory of the route is the apparent wilderness over which we were flying”, reflected Crampton. “There were no lights on the ground nor any sign of human habitation — quite unlike the rest of Europe… [We] covered our briefed route taking the target photographs as planned. It was all so quiet as to be distinctly eerie”. Their mission appears to have gone very smoothly and they successfully made their second KB-29P tanker hook-up over southern Germany, close to Fürstenfeldbruck, their nominated diversion airfield in case of problems. Improved weather over East Anglia enabled them to recover successfully to Sculthorpe.

It is now possible to make a clearer link between some of the likely key ‘Jiu Jitsu’ targets and the intelligence priorities of the day from a 1959 list compiled by SAC, declassified in recent years. This identified potential heavy bomber airfields in the western USSR that were then key to its own nuclear strategy. At least 15 of the top 20 of those airfields, described as priority one and two targets, were close to the routes flown by ‘Jiu Jitsu’, though it is not possible to be certain which were actually covered. Five were in Belarus including Orsha (Balbasava), Baranovichi, Babruysk, Minsk and Gomel (Prybytki). Seven were in Ukraine, most of them close to Crampton’s southern route, as far as the Sea of Azov including Pryluky, Poltava, Zhitomir, Stryi, Melitopol, Bykhov and Horokhiv.

For the northern route, three more included two in Russia, Pochinok and Soltsy, plus Tartu in Estonia. However, these were far from the only targets on their respective routes. The individual aircraft tracks as reproduced on small-scale maps are unable to capture the frequent changes of course the RB-45Cs made to capture, for example, the 126 air intelligence targets Crampton said they were assigned along the southerly route alone.

On their return, the SDF was quickly dispersed and the aircraft were returned to the United States. Within a few days, Crampton and Sanders flew one of the RB-45Cs, still in RAF markings, to Lockbourne AFB, as the 323rd SRS rotated aircraft back to the US. The following day they visited SAC HQ at Offutt. Sanders recalled, “We were debriefed a bit at SAC. Gen Curtis LeMay wanted to see us and say, ‘good show’. He was very pleasant to us and said, ‘you can go wherever you like, boys — we will take you in a Dakota for a week’s holiday’. We went to Washington DC”. Crampton and Sanders were both awarded the Air Force Cross and Flt Sgt Lindsay an Air Force Medal in the 1953 New Year’s honours list.

The SDF was reactivated in autumn 1952, although this was short-lived because British politicians were dissatisfied with the objectives. In particular, Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden strongly opposed this second mission plan, as he regarded it of greater importance to the “general American atomic offensive” than to British interests.

He also objected to the planned penetration as far as Moscow. Eden questioned again why the UK should undertake these highly risky flights when the US was not prepared to do so. Preparations were already very advanced when the cancellation came. USAF RB-45C pilot Stacy Naftel recalled bringing one of three aircraft to Sculthorpe in late October 1952, helping to requalify the RAF pilots, and saw the aeroplanes with their British markings applied during November. The missions were scheduled for 12-13 December 1952, but the aircraft returned to the US soon after they were called off, some still in RAF colours.

The flying logbook of navigator Flt Lt Richard Hales, who was due to participate in the December 1952 flights, is now on loan to the RAF Sculthorpe Heritage Centre. It records his training flight preparations, including profile and practice refuelling missions undertaken through November. His pilots included Naftel, Flt Lt Currell and Crampton.

The distance the three SDF aircraft had penetrated Soviet-controlled airspace in 1952 is astounding even today, especially in a relatively slow machine like the RB-45C. Operation ‘Jiu Jitsu’ demonstrated very clearly how closely the US and UK were prepared to integrate their efforts when there was perceived mutual self-interest. Nevertheless, it exposed the crews to significant direct danger.

A February 1954 minute requested approval for another ‘Jiu Jitsu’ mission that spring. It offered some insight into the 1952 flights and the Soviet response to them. “The Soviet air warning organisation is liable to error and delay; fighter reaction was slow; there was no evidence of an air intercept equipped night fighter, and […] height estimation was poor.”

Of the missions themselves, it added, “On the night of 17/18 April 1952 three successful flights were carried out over the Soviet Long Range Air Force bases in the Orsha and Poltava areas… Valuable results were obtained. Photographic cover was secured on 20 out of the known or suspected 35 Soviet Long Range Air Force airfields. Of the 20 airfields photographed, the material on nine was indifferent. There is still no cover on 15 airfields and nine with indifferent cover.”

Some of the poorer quality was probably because, unknown to the 1952 crews, a certain amount of their radar scope photography was degraded. The 35mm cameras mounted in two of the aircraft to photograph the AN/APQ-24 radar displays had been incorrectly focused. Even so, they had provided vital targeting materials for SAC and later RAF nuclear bomber forces.

One significant facet of ‘Jiu Jitsu’ that is largely overlooked was its long-term effect. It was the first post-World War Two aerial reconnaissance effort that involved deep co-operation between the RAF and USAF. Its organisation and conduct heavily influenced the pattern of future air reconnaissance and intelligence collection operations between the two air forces and governments that lasted throughout the Cold War, and continues to this day.;

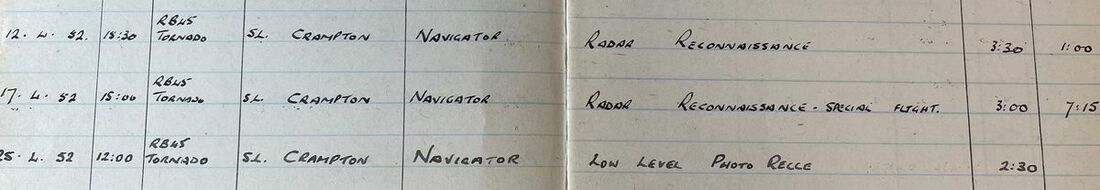

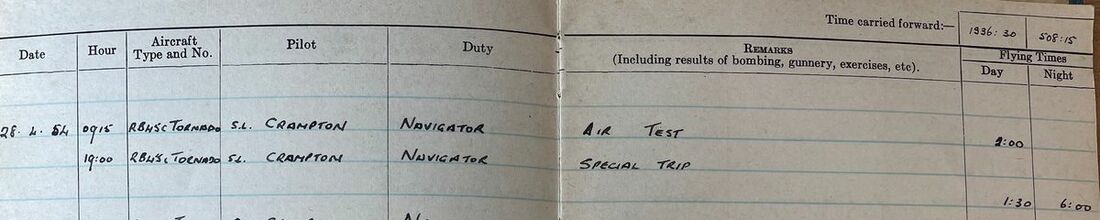

The Flying Log Books of Sanders clearly mark both Ops but unsurprisingly give no detail given the nature of their work:

'17.4.52. RB45 Tornado. [Pilot] S.L. Crampton. [Duty] Navigator. Radar Reconnaissance - Special Flight. 3hrs Day Flying. 7hrs 15mins Night Flying.

28.4.54. RB45c Tornado. [Pilot] S.L. Crampton. [Duty] Navigator. Special Trip. 1hrs 30mins Day Flying. 6hrs Night Flying.'

When his final Log Book entry was made in November 1962, Sanders had some 2,463hrs 20mins flying to his name. He was duly decorated by the French Government and claimed his Bomber Command clasp in later life, besides being presented with a Medal by the United States at a Symposium celebrating the 'Early Cold War Overflights' in Washington DC in February 2001; sold together with the following original archive:

(i)

His Flying Log Books (3), his Pilot's Flying Log Book (Form 414), covering the dates 18 November 1941-23 May 1942, his Royal Canadian Air Force Observer's and Air Gunners Flying Log Book, covering the dates 12 August 1942-29 July 1954, spine rather frayed and his Flying Log Book for Navigators, Air Bombers, Air Gunners and Flight Engineers (Form 1767), covering the dates 6 August 1954-21 November 1962, besides the aforementioned American Early Cold War Overflights bronzed Medal, 51mm and a good selection of copied research.

For his miniature dress Medals, please see Lot 343.

Subject to 20% VAT on Buyer’s Premium. For more information please view Terms and Conditions for Buyers.

Sold for

£20,000

Starting price

£12000

Sale 23003 Notices

'Credit for the research article observed below must also primarily go to Dr Kevin Wright, the details extracted from the original article he penned for the Aeroplane publication.'