Auction: 23003 - Orders, Decorations and Medals

Lot: 260

'Without Colonels Cyril Wilson and John Bassett there would be no Arab Revolt. Without them there would be no call for Lowell Thomas to promote T. E. Lawrence as a hero, no iconic 1960s, film, and libraries around the world would have space for other subjects. Wilson and Bassett shored up the revolt when collapse was a serious threat. Their lost stories show that the Arab Revolt could not have had its success without their unsung interventions.'

So wrote Philip Walker in Behind the Lawrence Legend: the Forgotten Few who Shaped the Arab Revolt

The exceptional D.S.O., O.B.E., group of ten to Lieutenant Colonel J. R. Bassett, Royal Berkshire Regiment & 2nd Imperial Camel Corps

Bassett was one of the forty Officers listed by T. E. Lawrence - 'Lawrence of Arabia' - in the preface to Seven Pillars of Wisdom as being able to ‘tell a like tale’ to his

During the Second World War he would tragically be taken a Prisoner of War by the Japanese in the Solomon Islands and by all accounts, brutally murdered on Ballale Island

Distinguished Service Order, G.V.R.; The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire, 1st Type, Military Division, (O.B.E.) Officer's breast Badge, silver-gilt; Queen's South Africa 1899-1902, 3 clasps, Cape Colony, Orange Free State, Transvaal (Lieut. J. R. Bassett. Rl. Berks: Rgt.); King's South Africa 1901-02, 2 clasps, South Africa 1901, South Africa 1902 (Lt. J. R. Bassett. Rl. Berk. Rgt.); British War and Victory Medals, with M.I.D. oak leaves (Lt. Col. J. R. Bassett.); Turkey, Ottoman Empire, Order of Osmanieh, 4th class breast Badge, silver-gilt, silver and enamel; France, Legion of Honour, 5th Class breast Badge, silver-gilt, silver and enamel; Egypt, Kingdom, Order of the Nile, Second Class set of insignia, comprising neck Badge and breast Star, in Lattes case of issue; Hedjaz, Kingdom, Wissam Al Nadha (Order of the Renaissance), 1st Type, 2nd Class set of Insignia, comprising neck Badge and breast Star, gold, silver and enamel, some light enamel damage to the Legion of Honour and the Hedjaz Insignia, otherwise very fine, a very rare group (Lot)

D.S.O. London Gazette 4 September 1918.

O.B.E. London Gazette 3 June 1919.

M.I.D. London Gazette 25 October 1916, 7 October 1918, 24 March 1919.

Hedjaz, Kingdom, Order of Al Nahda, Second Class London Gazette 24 October 1919.

The history of the Arab Revolt during the Great War is well documented but less well known are the details of the Order of the Al Nahda (Renaissance) which was bestowed by King Hussain Bin Ali of the Hijaz upon British subjects for their services during this period. In addition to the Order of Al Nahda King Hussein also instituted the Orders of Al Istiqlal (Independence). Initially little was known about these orders. The Foreign Office in London were, by the early 1920's, being asked for information concerning the awards - but having no information appealed to the then British Agency in Jeddah. A letter from the Foreign Office dated 31 December 1924 gives some insight:

'We are receiving inquiries from various quarters as to the origin and general history of the Orders of El Nahda and Istiglal of the Hedjaz. I find that the Foreign Office have themselves no particular information on the subject: hence my appeal to you. Could you perhaps kindly let us know anything you can about these orders, their history, origin, purpose for which they were instituted, and membership? We shall then be able to satisfy the curiosity of such different personalities as the Danish Minister and a representative of Spinks.'

At this time the Kingdom of Hejaz was in terminal decline and the acquisition of information was difficult. The response dated 28 February begins:

'To produce a complete reply to your letter of December 31st I needed a few details from the Hejaz Government, and as they have been more deeply interested in shells (not the conchologist's kind) than in decorations the last few weeks, I have kept the Danish Minister waiting.

The Order of the Nahda was established to commemorate the revolt of the Hejaz against the Turks. The first distribution was made on October 15th 1918, when Sharif Hussein declared himself King. It is supposed to be confined to people who actually took part in the revolt.

The colours are those of the Hejaz flag, viz. white, black, green and red. White, black and green have been the colours of the Arab movement since it began; the red was added by Hussein...If the kingship of the Hejaz should cease to exist, would there be a slump in these decorations, or would they, like a limited issue of postage stamps, become "rare" and expensive? It is always possible that Hussein would consider himself a sort of king "in partibus" and continue in that capacity to grant decorations.'

Indeed upon the incorporation of the Hejaz into Saudi Arabia in 1925 both orders became Trans-Jordanian awards and awarded by King Hussein's son Abdullah, later King Abdullah of Jordan and they now have become Jordanian awards. The Order itself displays the Hejira year 1334 (period 9 November 1915-27 October 1916 inclusive), in the centre two crossed Hijazi flags with a five-pointed star in the centre and the inscription 'His Servant Ali bin Al Hussein'.

British recipients of the Order of Al Nahda were published in the London Gazette, although other awards known to have been made were not promulgated. It appears that notice of awards were announced by the Arab Bureau in Cairo who acquired details as published in Al Qibla, being the Royal Hijaz Official Gazette. In most instances it seems that the Arab Bureau then forwarded the brevets and decorations to the responsible authority for onwards transmission to the recipient. The awards were announced on nineteen occasions between 24 October 1919 and 2 September 1924.

One of those whose name does not feature was T. E. Lawrence, 'Lawrence of Arabia'. It is thought that he was awarded the Second Class of Order of Renaissance, in recognition of his services to the Hijaz Government. His name is believed to have been listed in Al Qibla No. 320 of 9 Muharram 1339, corresponding with 7 October 1919. However as it is known that Lawrence had no time for awards and decorations, it is quite possible that he refused the Order.

Just 20 appointments of the 2nd Class Order to British recipients were made.

France, Legion of Honour, Fifth Class London Gazette 10 October 1918.

John Retallack Bassett was born on 27 October 1878 at Leighton Buzzard, Bedfordshire, the son of Frederick Bassett and Elizabeth Phoebe Bull. Commissioned 2nd Lieutenant into the Royal Berkshire Regiment, he went on to first see active service during the Second Boer War with the 2nd Battalion, being present on operations in the Cape Colony, the Orange Free State, and the Transvaal, and was out there when promoted to Lieutenant on 12 December 1900. Appointed Battalion Adjutant on 5 August 1903, this appointment came to an end on 5 August 1906, and he was then seconded from regimental duty on 15 December 1906 and posted to the Egyptian Army. Bassett was still on seconded duty when he was promoted to Captain on 2 June 1909.

By the outbreak of the Great War, Bassett was a Major on the Staff with the Egyptian Army, and hence did not gain entitlement to the 1914-15 Star. He was promoted to Major in the British Army on 1 September 1915, and with the situation in Sudan created by the ongoing Great War, was then involved in operations there, being 'mentioned' for intelligence work on the administrative side. He was also gazetted as a Governor of a Province in the Sudan on 25 October 1916, where he became a trusted member of General Reginald Wingate's inner circle. He was also rated for pay purposes as a General Staff Officer 2nd Grade as of 2 October 1916. It was almost certainly for his work as a Governor of a Province in the Sudan that Bassett was awarded the Egyptian Order of the Nile, 2nd Class Grand Officer Grade.

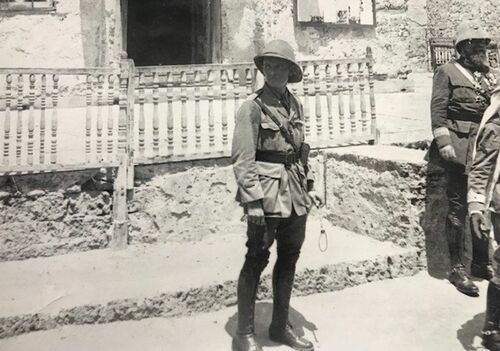

This position appears to have come to an end on 4 November 1916, and following this, he took up an important role as intelligence liaison officer with the French in the eastern Mediterranean, working closely with the British Eastern Mediterranean Special Intelligence Bureau. Bassett was then appointed an acting Lieutenant-Colonel, whilst in command of the 2nd Battalion, Imperial Camel Corps, from 23 January-12 March 1917 and seeing active service in the Sinai desert. During this period of command he is most noted for having led the Camel Corps into battle during the Raid on Bir El Hassana. The Raid on Bir el Hassana (Hasna) occurred in the Sinai Peninsula in February 1917. It was a minor action between an augmented Battalion of the Imperial Camel Corps on the one side and a score of Turkish troops plus some armed Bedouin on the other. The raid was the third of three actions fought by British forces seeking to recapture the Sinai Peninsula.

At this time British ships on the Mediterranean coast and the Gulf of Aqaba guarded the coast road via El Arish, and the road from Ma'an via Nekhl to the Suez Canal. Ottoman forces continued to occupy the area on the central way across the Sinai south from el Kossaima towards the Suez Canal, including Bir el Hassana and Nekhl.

General Archibald Murray, commander of the Egyptian Expeditionary Force, ordered attacks against both Nekhl and Bir el Hassana, which lay 40 miles north of Nekhl, between the Gebel Helal and the Gebel Yelleg. Three columns of cavalry and camelry set out with the goal of all attacking on 18 February. One column set out from Serapeaum, and another from Suez on 13 February 1917 to converge on Nekl. Bassett, commanding 2nd Battalion, Imperial Camel Corps, together with the Hong Kong and Singapore (Mountain) Battery, marched from El Arish, via Magdhaba. This column reached Lahfan on the 16th, and on the 17th advanced from Magdhaba. At dawn the next morning they surrounded the Ottoman Army garrison at Bir el Hassana, which consisted of three officers and 19 other ranks, reinforced by armed Bedouin. The Ottoman troops surrendered, but the Bedouin fired on the British, shattering Lance Corporal McGregor's ankle. One of the Turks who surrendered was Nur Effendi, who had commanded the Garrison at the unsuccessful British attack on Maghara on 15 October 1916. The troops searched Bir el Hassana and found 21 rifles, a few camels, and 2100 rounds of ammunition. After the surrender of Bir el Hassana, Bassett's force remained in position to capture any Ottoman force withdrawing back from Nekhl towards Bir el Hassana. On 19 February the Royal Flying Corps flew McGregor out with his leg in a box splint, while he sat in the observer's seat of a B.E.2c two-seater biplane. This was the first use of aeromedical evacuation by the British.

Bassett was next appointed a Deputy Assistant Quartermaster General as of 8 April 1917. It was then that he got involved with Lawrence of Arabia and the operations in the Hedjaz Desert of the then Trans-Jordan, now the Kingdom of Jordan during the Arab Revolt.

'Without Colonels Cyril Wilson and John Bassett there would be no Arab Revolt. Without them there would be no call for Lowell Thomas to promote T. E. Lawrence as a hero, no iconic 1960s, film, and libraries around the world would have space for other subjects. Wilson and Bassett shored up the revolt when collapse was a serious threat. Their lost stories show that the Arab Revolt could not have had its success without their unsung interventions.'

So wrote Philip Walker in Behind the Lawrence Legend: the Forgotten Few who Shaped the Arab Revolt. He continues:

'Bassett is one of the forty officers listed by T.E. Lawrence in the preface to Seven Pillars of Wisdom as being able to ‘tell a like tale’ to his. But Lawrence deliberately downplays the indispensable diplomatic and intelligence roles played by Wilson, Bassett and others in the Jeddah circle. Recognition of their essential roles would dilute the impact of the Lawrence-centred narrative.'

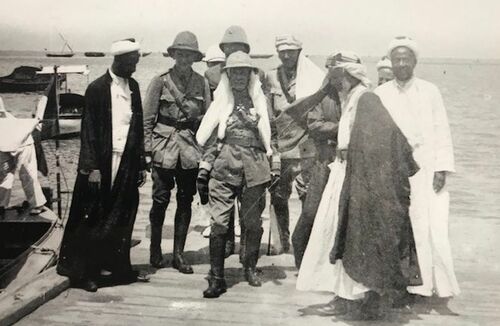

Bassett was sent to join the British Military Mission in the Hejaz where he met King Hussein and his son Feisal to discuss military strategy. Bassett gained information on Ottoman railway lines from a network of local spies, which even included the number of spare rails stockpiled at each station.

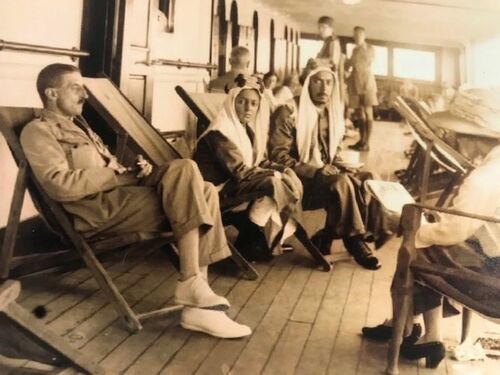

He was thrust into the high politics of the revolt almost immediately, deputising for Colonel Cyril Wilson, who was suffering from a life-threatening dysentery and evacuated for half a year to Cairo (he would later have to have a leg amputated). The British plans for the region had been leaked in the Sykes-Picot agreement, possibly direct from Lawrence to Prince Feisal. His father, King Hussein, was so shaken by what looked like British skulduggery that he not only threatened to pull the plug on the entire revolt but also talked despairingly of suicide. Bassett had to cope with this and the diplomatic fallout of the Balfour Declaration being made public. The British sent Bassett and Commander Hogarth, former Director of the Arab Bureau, to mollify King Hussein aboard Hardinge. General Wingate later expressed how much he valued Bassett’s key role in helping keep the revolt on an even keel:

‘From all Hogarth tells me you have “made good” with the King and are carrying on the Wilson tradition most successfully.'

Bassett stepped into the breach and brokered a number of vital meetings, sidestepping diplomatic snares before Hogarth’s arrival and helping steer Hussein back from the brink. On 8 February 1918, he delivered what was to become known as ‘The Bassett Letter’ from London Foreign Office to King Hussein. The letter, written in Arabic, dismissed the publication of the Sykes-Picot Agreement as an attempt by the Ottoman Empire to derail the Arab Revolt by creating mistrust between the Arabs and the British. It was this lie that eventually led Lawrence himself to alienation, disillusionment and depression. Bassett later shaped General Allenby’s approach after King Hussein had resigned in writing on 28 July 1918. Although Bassett thought this a bluff, he urged Allenby to press Whitehall to openly back the King against Ibn Saud incursion into Kurma. The Cabinet agreed, and the policy averted crisis and brought back Hussein once more.

Having cracked the cipher of the Ottoman intelligence secret service, Bassett analysed accounts that provided insight into a complex network of agents, deserters, tribal sheiks, factions and bribes that mirrored British activity. The reality of a hidden intelligence war was far removed from the legend of the Bedouin tribes rising as one behind ‘Lawrence of Arabia’. Following Ottoman surrender, Bassett was sent to interrogate Fahkri Pasha, the obstinate commandant of the Turkish garrison at Medina who had continued to resist after the official armistice. He explained to Bassett that it had been beneath his dignity to surrender to a mere Captain (Herbert Garland who was attached to Emir Abdullah’s forces). Bassett’s intelligence background persuaded him that Fakhri was hiding something and seized his diary and accounts, concluding that Fakhri had been intending a belated alliance with Ibn Saud against Hussein.

For his part in this pivotal period, he was rewarded with the D.S.O., O.B.E., French and Hadjaz awards, besides several 'mentions' to add to his laurels. In a bizarre twist, in 1929 Bassett married Evelyn Mary Gillman Burgess, a widow, and thus became stepfather to Guy Burgess, the future Soviet spy and defector. Andrew Lownie’s Stalin’s Englishmen provides an insight:

'The man Eve Burgess marries is a rather interesting man called Jack Bassett, a retired Army officer who’d served with Lawrence of Arabia in the Arab Bureau. He was an intelligence officer – indeed he had one of the first copies of Seven Pillars of Wisdom – but he and Burgess did not get on very well. You can imagine Burgess feels that this man has come between him and his mum, and he calls him The Colonel. He does everything he can to irritate The Colonel – there’s nothing you can do that irritates The Colonel more than passing the port the wrong way.'

To fellow scholars at Trinity College, Cambridge University, Guy always referred to his stepfather as a ‘professional gambler’. Although Bassett was a keen race-goer and lived near both Ascot and Newbury racecourses, it was likely that he funded Guy through the banking industry, into Eton and then one of the richest of Cambridge colleges, arguably sparking another of history’s great intelligence affairs, this time to Britain’s detriment.

Bassett was transferred to the Regular Army Reserve of Officers after the Great War, but ceased to belong to the reserve on attaining the age limit on 27 October 1933, retiring in the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel.

Journey's end

Bassett died whist e a Prisoner of War in the Solomon Islands. His death and those of the men under his command, are considered war crimes. The date of his death - 5 March 1943 - is the one ascribed by the Commonwealth War Graves commission. The actual date of his death is unknown. The following is an extract from the Report on War Crimes on Ballale Island by Major E.C. Millikin:

'A Japanese interpreter Higaki of No. 5 Compound RABAUL gave evidence about a party of 600 British Artillerymen from Singapore who left there by ship during Oct '42 arriving Rabaul 6 Nov '42. One man died on the voyage. The party staged at Kokopo (Rabaul) for about one week. 82 men were left here as too weak to continue their journey. This party was later put under the care of Higaki as he could speak English. These men, apart from 3 reasonably fit men left as cook and medical orderlies, were suffering from beriberi, malaria and other sicknesses. On 18 March '43 the numbers were down to 48 - Higaki took over at this stage. On Japanese surrender 18 men survived. Higaki states that the men told him that after a stay of one week at Kokopo the 517 fit men were put on a ship and departed for an unknown destination. He was unable, despite repeated inquiries, to find out anything about their fate.

This party of 517 appears to be the same one referred to in HQ First Aust. Army letter A27974 of 25 Jan '46 addressed to 23Bde, the differences being that the letter refers to a party of 512 leaving New Britain in Mar '43 by boat. Higaki is quite definite about the number 517 and the date approx. one week after 6th November 1942.

There is no doubt that a large number of the POWs were killed by Allied bombing, mainly as a result of the Japanese refusing to let them take shelter in slit trenches or air raid shelters. From evidence given by the Koreans, also that taken in other areas, it seems certain that the remaining PoWs round about June 1943 were killed and buried. The reason for this is not clear, the evidence pointing to :-

(a) The PoWs were of no further use due to being too weak for further work or else their task was finished.

(b) The Japanese feared an invasion by the Allies and did not wish the POWs to be discovered.

The method of killing is not clear, although evidence gathered in other areas is all to the point that at a certain time the PoWs remaining were killed. In the absence of an eyewitness the best evidence will be a complete report on the exhumation of the bodies. In view of the evidence gathered by me I am of the opinion that the only person who can be held responsible is the commander of the unit Lt Comd Ozaki.

Major E C Milliken NX.70429. 10th March 1946.'

Subject to 20% VAT on Buyer’s Premium. For more information please view Terms and Conditions for Buyers.

Sold for

£8,500

Starting price

£8000