Auction: 23003 - Orders, Decorations and Medals

Lot: 245

Sold by Order of a Direct Descendant

'On 7th December [1918], the Lowland Brigade crossed the border to the tune of Blue Bonnets. As we stood at the frontier post and watched the old Brigade swing by we could not help thinking of all those gallant souls who had gone west, owing to whose gallantry on many a stricken field we were still able, at the end of the war, to maintain our high standard of efficiency. For we always felt that those who had fallen in action were still with us in spirit, and that it was by reason of their presence that we had always been able, under the most trying conditions, to do our duty. It is a good old simple belief which has carried us right through the war...

Oh, make no mistake about it, religion is the mainspring of the Happy Warrior.

For those who have lost their dearest, to whom life must be a blank, it may possibly be some slight comfort to know how we all felt in the Lowland Brigade to those who had died with us. And it was the custom, in at least one battalion, after every battle, for the Battalion to parade as strong as possible, in close column.

Then the buglers played the Last Post while the Battalion presented arms.

There is little more to tell. But a saying of General Foy's, in his history of the Peninsular War, may be of interest. He has said, writing nearly a century ago, that the condition of the British soldier never retrogrades; but that, retaining all the good qualities that his pre-decessors had acquired, he superadds to these, from generation to generation, whatever of improvement each may have happened to produce. The history of the British Army in this last Great War fully bears out the assertion of the French writer.'

Brigadier-General Croft in reflective mood.

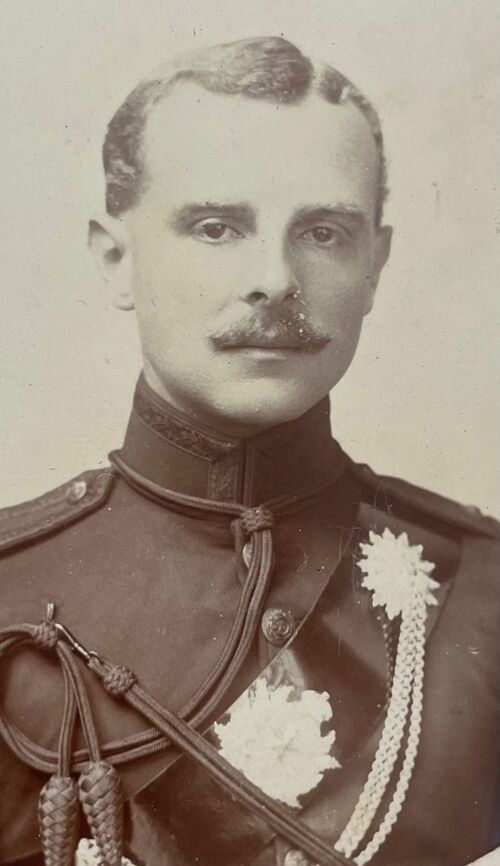

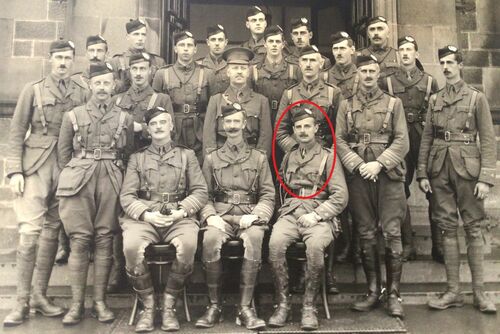

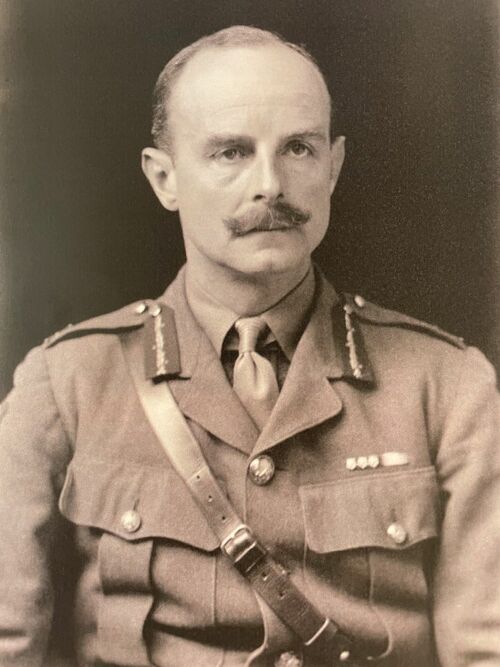

The unique 1935 C.B., Great War C.M.G., D.S.O. and Three Bars group of eleven awarded to Brigadier-General W. D. Croft, Scottish Rifles (Cameronians) and Royal Scots

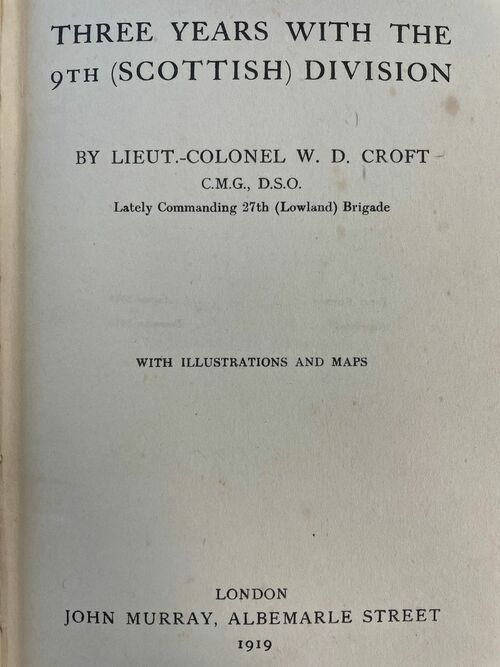

Croft cut his teeth on secondment in Nigeria, earning his first Medal & clasp - besides surviving being severely wounded by a poison arrow to the hand in a tense bush action; he thence had a truly remarkable Great War, rising to command his Battalion - crossing paths with Winston Churchill in the trenches along the way - and thence the 27th Infantry Brigade in the 9th (Scottish) Division, leaving an important first-hand account of their famous actions

Croft twice ignored perfectly acceptable 'Blighties' to remain in the thick of the action and earned the D.S.O. four times over, a feat achieved by only sixteen men in history to date, latterly becoming Commandant of the Royal Tank Corps and commanding a Brigade during the Mohmand 1933 operations; he returned to the fold during the Second World War as a Group Commander in the Cornish Home Guard and earned the 'Silver Fox' award for services to the Scouts

The Most Honourable Order of the Bath, C.B., Military Division Companion's neck Badge, silver-gilt and enamel, with full neck riband as worn; The Most Distinguished Order of St Michael & St George, C.M.G., Companion's neck Badge, silver-gilt and enamel, with full neck riband as worn; Distinguished Service Order, G.V.R., with integral top riband bar, with Second, Third and Fourth Award Bars; Africa General Service 1902-56, 1 clasp, N. Nigeria 1903 (Lt. W. D. Croft. Cameronians.), officially impressed naming; 1914 Star, clasp (Capt: & Adjt: W. D. Croft. Sco: Rif.); British War and Victory Medals, with M.I.D. oak leaves (Brig. Gen. W. D. Croft.); India General Service 1908-35, 1 clasp, Mohmand 1933, with M.I.D. oak leaves (Brigadier W. D. Croft. C.M.G., D.S.O.); Defence Medal 1939-45; France, Republic, Legion of Honour, breast Badge with rosette upon riband, gold and enamel; Scout Association, Silver Fox Award, hallmarks for Birmingham 1948, with full neck riband as worn, mounted as worn where applicable, good very fine (11)

Since the establishment of the Distinguished Service Order in September 1886 by Queen Victoria, a little under 17,000 awards have been made. Of those, just 1,910 have earned the Second Award Bar. Of those, just 143 earned the Third Award Bar. Of those, just 16 to date have earned the Fourth Award Bar. 7 Fourth Award Bars were made during the Great War, 8 Fourth Award Bars during the Second World War and 1 for Korea. Our research suggests just 9 such awards remain with the family or Private Collections.

Numismatically, they are the rarest of the rare when considering the award is open to all services and since 1993, available to all ranks. The list of those awarded the D.S.O. and 3 Bars reads like something of a Who's Who:

Great War -

Commander A. W. Buckle, Royal Naval Division. Medals held by the Imperial War Museum.

Brigadier General W. D. Croft, British Army.

Lieutenant-Colonel W. R. A. Dawson, Royal West Kent Regiment.

Brigadier-General A. N. Strode-Jackson, C.B.E., Loyal North Lancashire Regiment. Medals sold by DNW, December 2007 (Hammer Price £40,000).

Lieutenant-Colonel R. S. Knox, Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers. Medals sold in these Rooms, December 1997.

Brigadier-General F. W. Lumsden, V.C., C.B., Royal Marine Artillery. Medals held by the Royal Marines Museum, by whom they were purchased in 1973.

Brigadier-General E. A. Wood, C.M.G., King's Shropshire Light Infantry. Medals held by the Soldiers of Shropshire Museum.

Second World War -

Air Chief Marshal B. E. Embry, G.C.B., K.B.E., D.F.C., A.F.C.. Medals sold in these Rooms, April 2007 and now held in the Lord Ashcroft Collection

Lieutenant-General B. C. Freyberg, 1st Baron Freyberg, V.C., G.C.M.G., K.C.B., K.B.E.. Medals held by the family.

Captain E. A. Gibbs, Royal Navy.

Lieutenant-Colonel R. B. 'Paddy' Maine, Special Air Service Regiment. Medals held at Regents Park Barracks.

Admiral R. G. Onslow, K.C.B., Royal Navy.

Brigadier A. S. 'Jock' Pearson, C.B., O.B.E., M.C., Parachute Regiment

Group Captain J. B. 'Willie' Tait, D.F.C. & Bar, Royal Air Force. Medals held by the Imperial War Museum.

Captain F. J. Walker, C.B., Royal Navy.

Korea -

Major-General D. A. Kendrew, K.C.M.G., C.B., C.B.E., Leicestershire Regiment. Medals held by the Regimental Museum.

C.B. London Gazette 1 January 1935.

C.M.G. London Gazette 1 January 1919.

D.S.O. London Gazette 1 January 1917:

'For conspicuous gallantry in action. He showed great courage and initiative in organising and supervising a successful attack. He established posts before dawn and joined them up the following night under heavy fire. He has previously done fine work.'

Second Award Bar to D.S.O. London Gazette 10 January 1917.

Third Award Bar to D.S.O. London Gazette 27 July 1918:

'For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty. He constantly showed the greatest courage and skill during many days' operations in command of a brigade. His H.Q. were placed close behind the firing line, as he rightly judged that the situation required his closest supervision. Owing to the movements of troops on his flank, it was necessary for the brigade, already weakened by many casualties, to hold a much-extended front. Without resolution of the highest

order, and constantly exposing himself to machine-gun and rifle fire, it would have been impossible to hold the line so long and withdraw as a fighting organisation.'

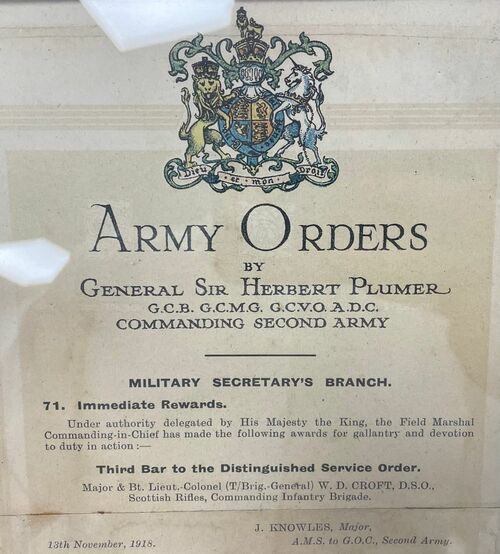

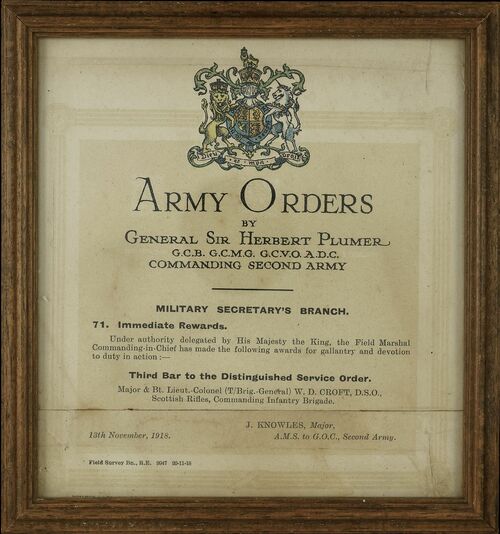

Fourth Award Bar to D.S.O. London Gazette 15 February 1919. The citation followed on 30 July 1919:

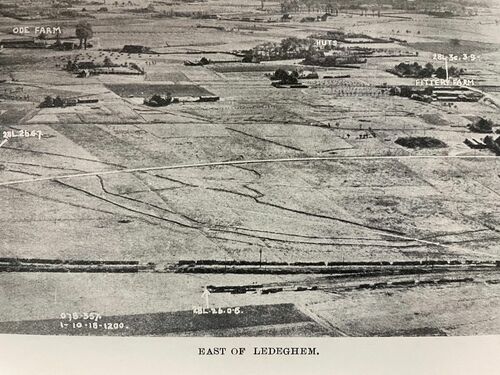

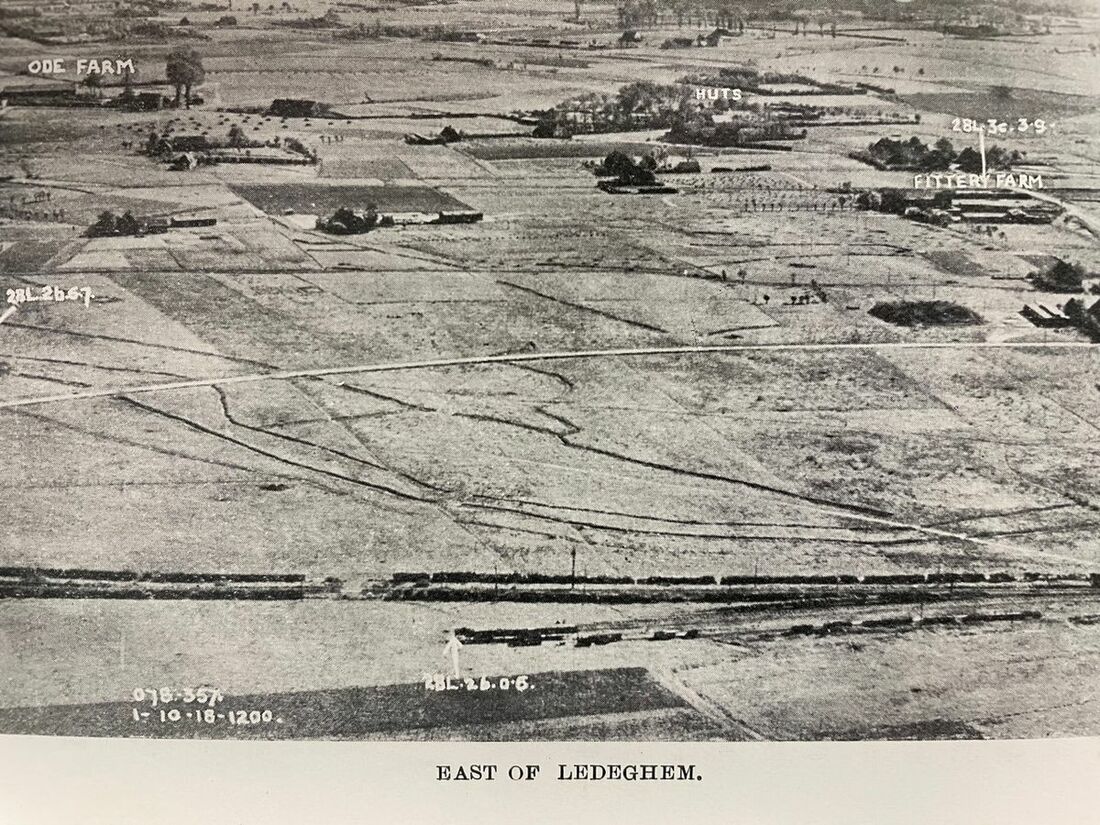

'As General Officer Commanding 27th Infantry Brigade. From 28 September 1918 onwards he displayed the utmost energy, skill and gallantry in the command of his Brigade, notably on 1 October, when his right flank was exposed and heavily attacked at Ledeghem. His handling of his brigade on 15 October, recovering in his overcoming all opposition and reaching the line of the Lys, and thus attaining all his objectives.

On the occasion of the crossing of the Lys on the night of 16-17 October, which necessitated his crossing in daylight under heavy machine gun fire at close range to visit his Battalions on the eastern bank, his example and confidence inspired his troops, who though strongly counter-attacked and heavily shelled, maintained their position until relieved.'

French Legion of Honour London Gazette 21 August 1919.

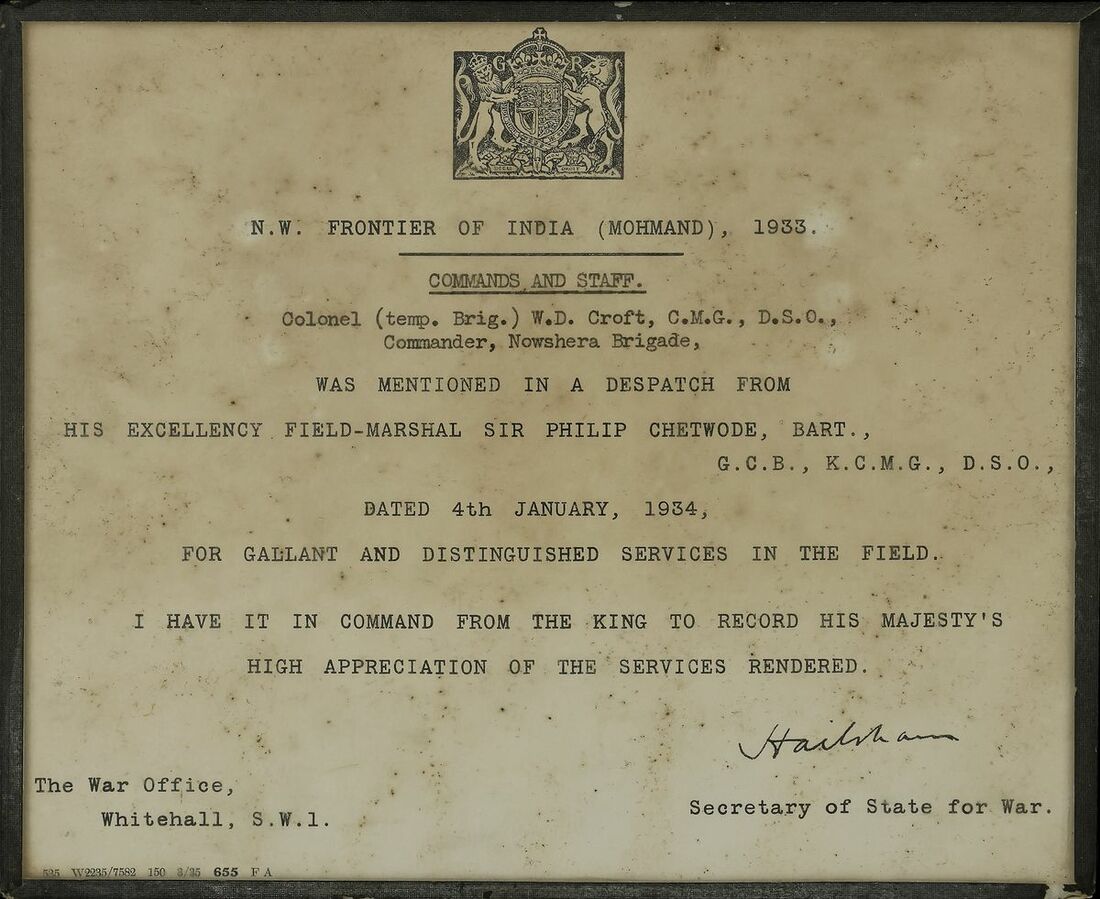

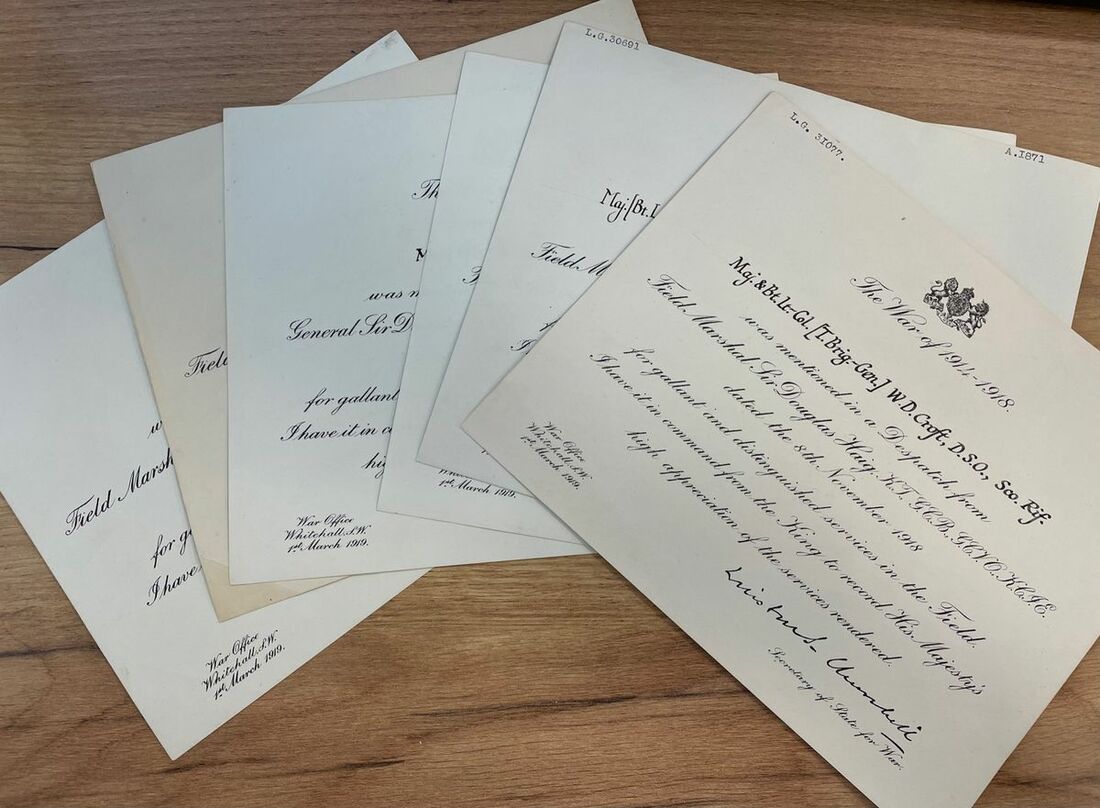

M.I.D. London Gazette 22 June 1915, 1 January 1916, 4 January & 22 May & 11 December 1917, 20 May & 20 December 1918, 5 July 1919, 4 January 1934 (Mohmand - N. W. Frontier).

24 'N. Nigeria 1903' clasps issued to European Officers.

Of the four Brigade Commanders who earned the clasp 'Mohmand 1933', this example is unique to the British Army, the others all being from the Indian Army. The others were issued to Brigadier (later General Sir) Eric de Burgh, Brigadier (later Field Marshal Sir) Claude John Eyre Auchinleck and Brigadier The Hon. (later Field Marshal The Right Honourable The Earl Alexander of Tunis) Harold Rupert Leofric George Alexander.

William Denman Croft was born on 15 March 1879, the third son of Sir Herbert Croft, 9th Baronet, of Croft Castle, Leominster and the Conservative MP for Herefordshire. Young Croft was educated at the Oxford Military Academy.

Initially commissioned 2nd Lieutenant into the 4th (Militia) Battalion, King's Shropshire Light Infantry in February 1898, he was advanced Lieutenant on 28 June 1899. He received a commission in the Regular Army when transferred to the Cameronians (Scottish Rifles) as a 2nd Lieutenant on 7 March 1900, replacing an officer who had been killed in the Boer War.

Seconded to the Colonial Office in 1903, Croft shared in the expedition and campaign in the areas of Kano, Sokoto and Birni from in 1903 in Northern Nigeria, with Lieutenant W. D. Wright of The Queen's (Royal West Surrey) Regiment earning himself the Victoria Cross in the action on 26 February. He clearly was not made aware of the fact he had earned his first - and uniquely named to the Cameronians - Medal & clasp with the 2nd Northern Nigeria Regiment, for it was not until January 1956 that he claimed it (WO/100/391). Croft remained in Nigeria from 1903-07 and was severely wounded in the right hand by poisoned arrows when out on patrol in 1907, which ended his posting.

Returned to the 2nd Battalion, Scottish Rifles, he was then selected in April 1911 for appointment as A.D.C. to the Governor & Commander-in-Chief of Sierra Leone, a position held until July 1912. Just before his departure, Croft displayed his athletic skills in settling a bet with a brother Officer. In an hour he completed a mile walking, running, cycling, riding, skulling and swimming.

Promoted Captain in March 1912, he was made Adjutant of the 5th Battalion in the Territorial Force in January 1913. It was with this unit that he first landed in France on 2 November 1914 following the outbreak of the Great War. It wasn't long before he was identified as being more than suitable for higher command and assumed command of the 11th Battalion, Royal Scots in December 1915. As part of the 27th Lowland Brigade in the 9th Scottish Division, he gallantly led his Battalion through the trials they would face until 13 September 1917.

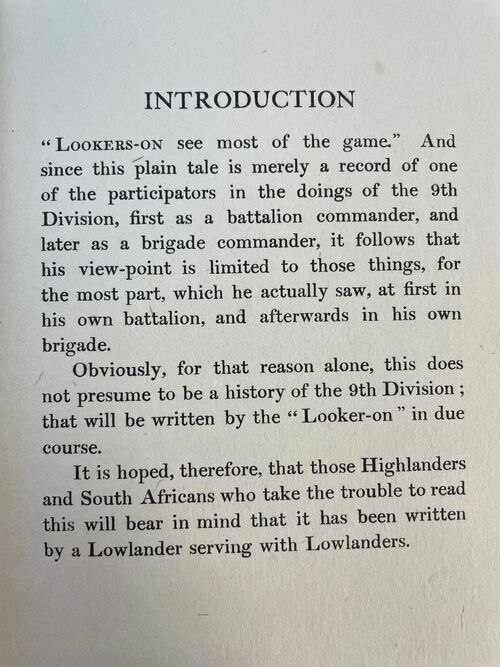

In this period he would lead them through the Battles of Somme, Vimy Ridge and Arras to name but three that stand out in his excellent work Three Years with the 9th (Scottish) Division. His views on his joining the Division:

'"Major Croft to proceed at once to command the 11th Royal Scots, 9th Division."

The orderly-room sergeant handed in the message at our somewhat battered house, or remnants of a house. I greeted the news with mixed feelings. In the first place it had been my fortune to bring a certain famous territorial battalion out to France in the autumn of 1914; also I had been two years with this battalion before the war, and consequently had a pretty shrewd idea of the good points and the bad.

The quality of that particular battalion was of a very special kind, and I didn't feel inclined to start new friends and all that kind of thing. On reaching the divisional headquarters I got shock number one-nothing less than a long and intimate talk with such an exalted personage as the divisional commander.

Now we had been an attached brigade before coming to the 9th Division, a no-man's-child among divisions, and consequently we didn't see much of divisional commanders, who naturally paid more attention to their own families. I was told all that there was to be told about my new battalion by a pretty shrewd observer.

Next morning I had my first experience of the Salient. It was the least happy of the four trips the 9th Division took to that delectable spot, because on the other occasions things were too exciting to give one time to "think of being a dog."

And dogs we were in 1915 - the under dog!

Pah! How we loathed it all from the moment we got inside that bloody Salient: overlooked everywhere; shelled from every quarter; and it rained all the time.

Next morning we went up through Ypres in pouring rain - what an abomination of desolation - the brigade headquarters, a snug little place on Zillebeke Lake, rather like a ship's cabin. At this time Ian Hay, with his First Hundred Thousand laurels thick upon him, was machine-gun officer. The brigade never fared better than when he was mess president.

Sanctuary Wood in 1915 was indeed a wood and not a mere collection of half-burnt matches, which it became during the Passchendaele show two years later.

It is always an unpleasant job taking over a new battalion. One doesn't know a soul; moreover, battalions being usually conservative often resent the intrusive C.O.

Let it be remembered that the division had lately come out of the biggest battle [Loos] so far known in the world's history, these men who not a year before had never thought of war; and with no time to stop and lick their wounds, they had been moved straight up into the Salient, for very good reasons doubtless. But it was a bit stiff on half-trained troops such as we were at that time; for we had no real discipline in us, only a splendid keenness to go all out and die game.

Don't think for a moment that one belittles such a spirit-it won the war, there is no doubt of that; but discipline is necessary, and we who have it now are the first to admit the need of it. Battalion headquarters was a "Bairnsfather" dug-out near the cemetery on the edge of the wood; its shelter was purely moral, and none but fools would have built it, much less have lived there; for it was under full view from the Boche, and was a datum for his 5.9's when he felt in a playful mood, which was pretty often.

I mind me of a place called the Birdcage, which gazed proudly down on our communication trench from battalion headquarters to the front line. For days the enemy would never interfere with the trivial round; and then - the best man in the battalion would die by a sniper's bullet.

In civil life it is extremely difficult for the average man to discover and sort out the Men from the Monkeys: in war there is no such difficulty; for when death is a near neighbour the mask of convention is torn away, and one can gaze into a man's soul. Three A.M. in the front line on a cold winter's morning was therefore selected as a suitable time for an introduction to the company commanders.

Reader, come down the line and be introduced to two of them; one who survived, and one whose "name liveth for ever."

"The Bart.," a Scottish baronet with a long pedigree and a lean purse, unravelled his lanky form from the leaky shelter and sank up to his fetlocks in mud.

"Rather a long line for a weak company."

"But there's a swamp on my left flank, sir, and the wire is good in front." Always an optimist was Old John.

"The Boche are right underneath us"-this to a question about the hostile mining operations - "but Kirky" (one of the subalterns temporarily employed on tunnelling) "has the situation well in hand."

"Any sniping?"

"Not much, and they're damn bad shots."

"You are rather an unfortunate height." He stood over six feet.

"Oh, they won't get me; I'll watch it."

They got him shortly afterwards in that very spot, but luckily only a temple graze.'

He also crossed path with another Battalion Commander who would gain laurels with the 9th Division:

'At the end of our five weeks we were reviewed by our Army Commander, General Plumer, and that always meant fighting. To our intense astonishment, however, we were sent into a very quiet bit of the line: but the knowing ones knew that Windy Bill had not earned his sobriquet for nothing.

And they were perfectly right. Relieving another division is always a loathsome business, and this relief was no exception. I went up to take over my little bit with Winston Churchill, who described himself as cavalry soldier run to seed; all the same the Service lost a good soldier when Winston took to politics.

It was indeed a peaceful spot. I saw only one shell-hole near the front line, and I was told in an awed whisper that it had arrived but the day before!

We went into Plugstreet Wood with our tails well up and pipes playing, for we were fit and hard, and ready to cope with the Boche on level terms once more, thanks to that Heaven-sent rest; and God help the Boche when taken on under such conditions by a Scottish division.'

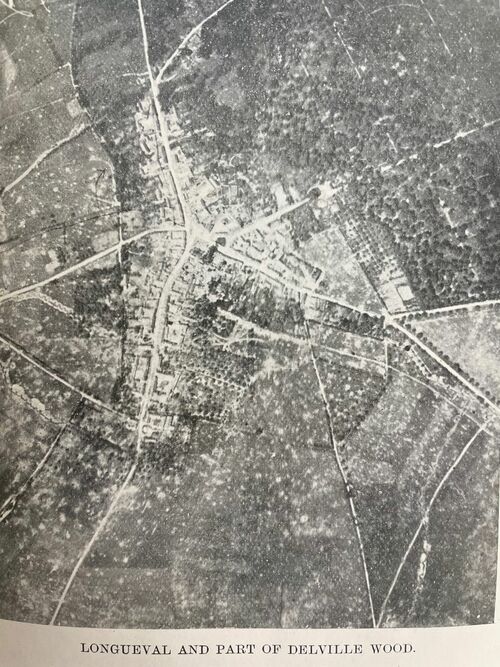

Churchill himself commanded the 6th Battalion, Royal Scots Fusiliers for some 125 days, in a period which saw them take 138 casualties. Croft himself was gaining in confidence and skill with his new charge, it was proven to be vital in the crucible that his Battalion would face during the Battles of the Somme the following summer. His unit would be held in Reserve during the First Day of the Battle of the Somme, after which Croft and his unit moved up and he found himself as Commandant of Montauban. Their next test came when they were given the leading role at Longueval:

'Shelling in a wood, as everyone knows who has tried it, is far worse than anywhere else, not excepting a village. As Montauban was the first village which we had taken and held in the war, it was naturally an object of considerable interest to brass hats.

They came in swarms, and notably there came an ex-minister of war whom I had much pleasure in carpeting before our divisional commander for walking about my preserves without so much as a "by your leave." After a week of this existence we were relieved by our old friends the Watch, and we went back to Billon Wood to wash and brush up for the coming battle. Here I was ordered to go sick by our brigade commander.

However it wasn't likely that one would go back with our big battle in prospect, and so I managed to keep out of the way until we started for our night march. And the dear old chap was too busy to notice me. Never would I have forgiven myself for missing that battle.

For on the 14th July 1916, the British Army performed one of the finest feats which have ever been done in war; to wit, a night march to a position of deployment within 500 yards of a vigilant enemy, then a crawl forward on hands and knees, to be followed at zero by the assault of a strongly wired and entrenched position which had suffered no previous bombardment to shake the moral of the defenders. And, in addition, Trônes Wood on our right rear, in fact very nearly directly behind us, was as yet uncaptured!

The cool daring of the thing ensured its success. And how it appealed to our lads! This was the sort of business for which they had joined up, not brutal, bloody murder, to which they had been accustomed for over a year.

"Always endeavour to surprise and mystify your enemy," should be, and must be, the soldier's first maxim, otherwise he is not likely to be much of a success in war. I shall never as long as I live forget starting out on that great venture.

On nearing Montauban, where the Boche was indulging in his usual antics - how he hated villages, the Boche - the whole brigade got into single file. We were leading battalion, and were fortunate enough to miss the shelling of the western outskirts of the village. But alas, it came down on the 12th Royal Scots who were immediately behind us, and got their colonel - Budge.

Incidentally it converted what would have been a complete success into a partial one. For Budge had been entrusted with rather a complicated wheel which was eventually to clear the village.

Had he lived, his fine battalion under his able leadership would have undoubtedly succeeded in the task; but it was not to be, and Longueval was not finally cleared of the enemy for some weeks.

Even now I cannot speak without deep regret and sorrow for one of the finest regimental officers in the army. He knew he was to die, knew it perfectly well; his one hope was that he would die in the hour of victory.

On reaching Caterpillar Valley, 1000 yards in advance of our front line, we met Norman Teacher, our brigade major, cool and alert as even. He had been engaged throughout the night in watching the Boche trenches with a party of scouts; a ticklish job, and he was mightily relieved to see us. There wasn't much time to waste, and we were barely in position before the move forward began. As I had a last look round, and passed a word or two with old friends, one little thought how few would be standing up in a short time. I spoke to Lemmy about his communications - he was now signalling officer - and I never saw him alive again.

Our C.R.A. gave us a creeping barrage on this occasion, the first time, I believe, that such a thing had ever been attempted. In this, as in many other matters, the 9th Division were the pioneers for that most successful form of attack.

For the benefit of those who do not know, a creeping barrage does not really creep at all. It consists merely of a succession of lifts at certain short intervals of time, and thus enables the infantry to keep quite close, and to smother the hostile trenches before the enemy has time to lift his head and function as a foe.

We found our wire uncut, all in the dark, remember, when men's nerves are prone to falter. But the officers and N.C.O.'s went gallantly forward to the business of wire-cutting in face of a cruel machine-gun fire, promptly taken on by Winkle-gallant old Winkle-with his two Lewis guns. In less time than it takes to write about it he had them cold, firing high over our heads at first, and later silent.

The Argylls were on our right, and I shall never forget their old pipe-major strutting up and down a certain well-sniped road near the village, while we cowered in a ditch alongside.

Someone pulled him down eventually, and his colonel sent him back to the transport lines, from which he made several attempts to get back to his battalion.

Our leading companies were right on their mark; but the wheel of the 12th Royal Scots did not come off, as Budge and most of their officers were knocked out. The men went forward, a gallant mob with no leaders, into the village. But they did not know what to do when they got there.

We found the Scottish Rifles had secured our left flank. And so, under galling fire from snipers in the apple-trees, we dug ourselves in with speed. We had sustained heavy losses, for Henry and Jack Cowan had been killed at the wire; L and the Bart. were wounded and missing respectively. Then Mabin, temporarily commanding the Bart.'s company, was killed later on in the morning, in the place where he knew he was fated to die. And the Highlanders had suffered even more than we had. What their casualties were I never knew; but Scotland knew, and so did South Africa; for later on the South Africans came into it at Delville Wood.

Remember this is not a history of the 9th Division, but merely the rough notes of one who was with that division: only a battalion commander with view-point necessarily confined to those happenings which he himself saw.

One is always chary of writing about things concerning which one had but second-hand knowledge.

The casualties of my battalion in that first Somme battle were over 600, and 24 officers; and the great majority took place from zero to zero plus one hour-practically at dawn.

No sooner had we consolidated our line than our troubles began. At first we blazed away, with much expenditure of ammunition but with little result at fleeing Boches and snipers.

It struck me pretty forcibly that there was something uncommonly like a rout in the opposition. For they were most obviously "hareing" shamelessly for home, and those who were not were likewise obviously "getting their skates on." I begged and implored someone to send cavalry to complete the victory.

But no doubt there were strong reasons against this course; reasons which we simple soldiers could not see, for all away up beyond High Wood were fleeing Boches.

That was the first of three occasions on which I asked for cavalry; the other two being at Arras on 9th April 1917, and again at Broodseinde Ridge on 28th September 1918, though really on the last occasion I was merely a spectator, the divisional commander doing the asking.

Masses of cavalry are normally too unwieldy for the fleeting opportunity. And so it seems to me that we need to hark back to the old days of divisional cavalry, seeing that on those three occasions a squadron would have been of priceless value. The employment of cavalry must be left to the man on the spot, not to the man-however great a genius he may happen to be who sits about 20 miles back.

It is not a mere question of numbers, but of moral effect, which a squadron of cavalry is quite big enough to ensure. For the larger the number of troops who abandon their arms the greater the panic; and we just wanted someone to keep them on the run and not let them get their heads up, and then their hearts up, and then start shouting, "Let us die for the Fatherland," and then give it us all to do over again!

Well, we soon saw that the foe, since he found that no one followed him, began to come back; first in twos and threes, then in larger numbers. Then a party began wiring on the high ground just above High Wood.

There were some subterranean passages right through the village of Longueval against which it was rather difficult to compete. The Boche had entrances well on his side of the village, and when things got a bit too warm for him down he would pop like a sewer rat by means of bolt-holes in most of the houses.

He nearly got the combined battalion headquarters of the Seaforths and Watch. It was at night, and they were having food, when one of the battalion runners who had been nosing about suddenly rushed in to say that the Boches were next door. As their front line was some considerable way in advance this was particularly cheering intelligence.

My battalion was ordered to take the northern end of the village. It was very difficult to reconnoitre owing to the sniping; however, we gave them a real good doing with Stokes and that funny old trench mortar which looked like half a dumb-bell, and then we attacked with one company, while another was ready to exploit as soon as the leading company gave them room to manoeuvre. South Africans were attacking on our right, in Delville Wood; as a matter of fact we had to finish up at the bottom of the hill.

And as we were already commanding that more side of the village it was not a particularly necessary operation from our point of view.

We tried and tried all that day to cut

through the impenetrable undergrowth stuffed with machine guns, but our progress was slow and slight. The South Africans had no better fortune in the tangle, and late in the afternoon we gave up the attempt. Tuner and Sergeant A-, afterwards adjutant of the 11th Royal Scots, had worked like Trojans, and I was satisfied that they had done all that was possible in the way of leadership.

The men were splendid too, always responding gamely to the call of their leaders. When these two got back they found that

they had left a man out, and they knew that he was wounded. Then Turner and A-, with-out the slightest hesitation, went back to get him; went back into that horrible tangle with machine guns shooting at point-blank range; went back to absolutely certain death, so far as they knew, in order to rescue a comrade from the tender mercies of fiends. Remember, these two had been on the rack for three days and three nights, and on the top of that they had been fighting all day under close machine-gun fire which had killed several of their men.

In all V.C. stunts the conditions are as important as the deed itself, and this deed was on all fours with many a pre-war V.C.

Turner got the D.S.O., and was killed at Arras next year. A got the D.C.M., and a commission. He survived the war.

It poured with rain all that evening, and when it got dark we had another try. This time Wheatley, and Tredgold, and Sergeant-Major P- were the heroes of the night.

The Borderers attacked on our right through the wood itself, and, taking advantage of the darkness, we tried a house-to-house visit. It was, as I said before, a pouring wet night, and the Boche, who did not expect us, was taken completely by surprise. A Company got in some dirty work with the bayonet; the Borderers got their objectives too. Then the same old game started again. The Boche popped up behind our fellows and gradually we got fewer and fewer. Wheatley was killed by a sniper at the north end of the village; a better or more conscientious officer never died for his country.

Then Tredgold, his subaltern, had a fearful time in keeping his end up, in maintaining touch with the Borderers who were on the other side of the main street-to cross which one had to run the gauntlet of a machine gun-and in getting his wounded away. At ten o'clock that morning we got them back to the top of the hill, from where we could shoot the Boche instead of the Boche shooting us.

I always thought that we were too prone to fight for each square yard instead of waiting till we were absolutely ready, involving fresh troops, and then going for the acres. It's not a bit of good asking stale troops to come with a wet sail.

Next morning I had a most happy shoot with Usborne. He had managed to get some wire up, and from our trenches we had a perfect view of the battlefield round High Wood. We made particularly good practice on the junction of an open track with a sunken road. Usborne got this Boche thorough-fare absolutely taped. And, letting the innocent Boche come gaily along the track all unsuspecting of evil, he would give his fire order so that the shell arrived at the junction just about the same time as the Boche. We must have avenged a few of our people during that shoot.

After some days of this sitting down in battle trenches and getting battle shelling we began to wonder when a relief was due, including even that most blatant fire-eater, the Bart., for to my great relief he had turned up eventually after getting "wandered" from his company and mixing himself up in a side scrap with a party of Argylls. He was blown up and knocked out for a bit, but it didn't prevent the hardened old sinner from rejoining for duty with his beloved Don Company as soon as he could remember things.'

A remarkable first-hand account of an action for which historians have spilled plenty of ink attempting to cover. Removed from the line, they went into Reserve on the lee side of Mountauban and were lucky when the German gas bombardment passed over them. The Division were replaced two days later.

Having reformed and got back to strength, they were put back onto the Somme and were thrown back towards High Wood, with the Royal Naval Division and a Division of London Territorials for company. The Naval Division '...caused some perplexity and considerable amusement, for they were very nautical.'

His gallant Scots forged on and captured Snag Trench, at great cost to the 104th Saxon Regiment which they came up to. Unsurprisingly, they also came across a great many South Africans who had made the ultimate sacrifice, including '...a large party at full stretch with bayonets at the charge - all dead; but even in death they seemed to have the battle ardour stamped upon their faces. They were led by their Officer, a magnificent specimen of manhood.'

Through it all, they eventually made it and captured Bapaume, being personally thanked by the Corps Commander for their work. Quite a relief it must have been that Croft and his charges were provided transport by way of London Omnibuses to remove them from the front. As often happens in War, it went from the sublime to the ridiculous and the unit were selected to immediately scrub up and provide a Guard of Honour of the King of Montenegro. So it was 'The Bart.' was in command of the Guard when the King '...made some remark to him which sounded like Malayan, so he answered in the same language. The Bart. did not receive a decoration on that occasion.'

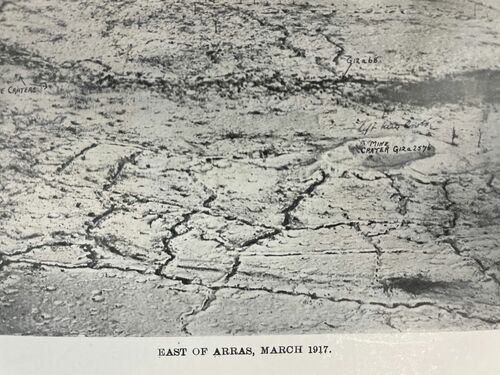

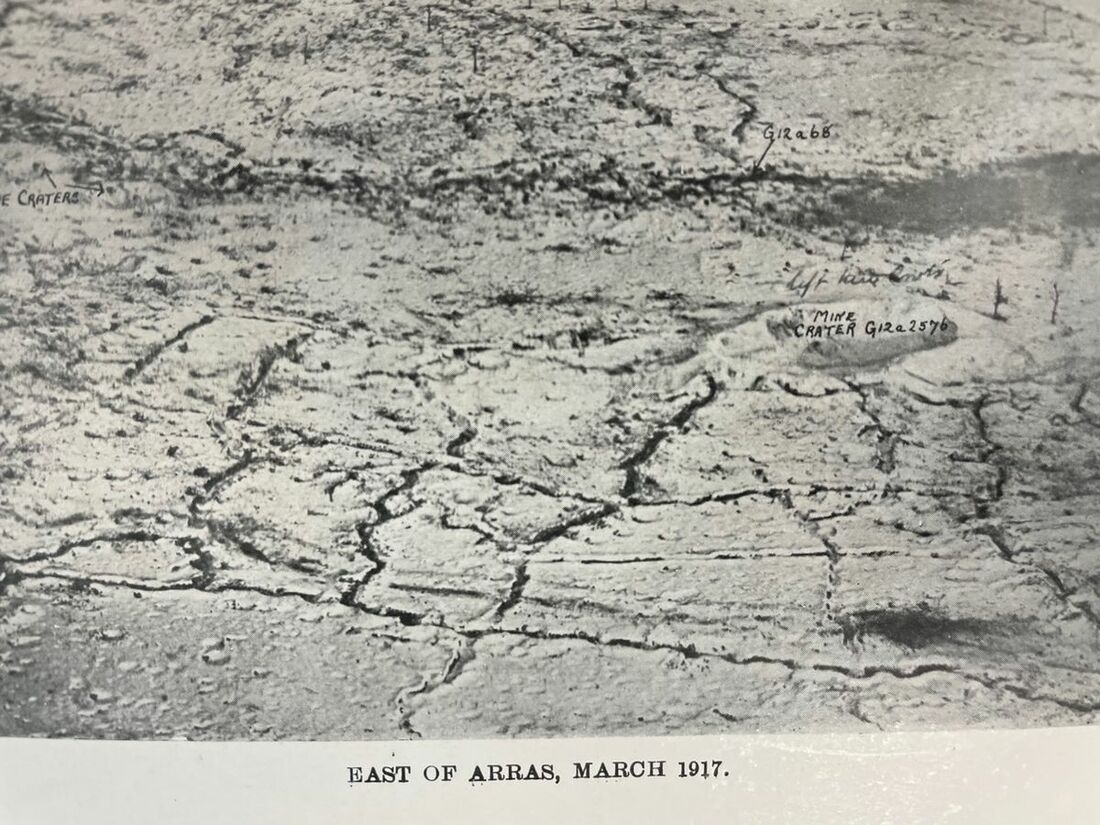

Croft did however earn his first two D.S.O.'s, these coming less than three weeks' apart in early 1917, together with further 'mentions' for his laurels. Most accounts of his career state Croft earned 10 during the Great War, of which this cataloguer has been able to trace eight. He remained in command of his Battalion until September 1917. Perhaps the most striking action came when he led the unit at the Battle of Arras on 9 April 1917:

'When our turn came to cross No-Man's-Land we found the most appalling mix-up of the division. Even at that early hour there were Highlanders who had wandered on my left, and also South Africans.

Most of my people were too much to the right, and it was all one could do to get them back into their proper places in time for the advance on our second objective, the railway line.

As we walked along we noticed Thorne, who commanded the 12th Royal Scots, lying dead. He was a fine fellow and, curiously enough, he had lost his brother, a wing commander, a few days before.

Losses had been heavy, and we were getting it in the neck from M.G.'s on the railway it was at this time that poor Loftus dropped by my side, knocked over by a machine-gun bullet. We made him as comfortable as we could, but we had to get on, for the attack was just due to start. Then down the slope went that splendid throng of lads, and up they climbed to the railway close under our barrage.

Nothing could stop them that day, though there were Boche machine guns everywhere, and skilfully placed too. In some cases they were placed in tunnels under the embankment.

In that advance Jimmy, who commanded a company of the 12th Royal Scots, was wounded for the second time that day. Part of his hand was dangling, quite a nasty wound, and he calmly shot it away with his revolver. In the attack on the second objective, where he had no business to be except through his keenness to be in at the death, he was very badly wounded all round the groin by a shell, which burst at his feet.

Though he was suffering agony he refused to be taken down on the stretcher till all his men had been first attended to. So great were his agonies during this waiting period that a sergeant twice prevented him from turning his revolver on himself. The doctors all told me that Jimmy was bound to die, but he walks about, with help, to this day.

It took us some time we were on the left flank of the division to clear the railway cutting, which was stiff with dug-outs and contained many Boches.

We got hundreds of prisoners here. One of our sergeants who was inclined to look upon the wine when it was red, managed to procure, by means best known to himself, some Boche liquor. A Boche officer looked out of the dug-out and politely offered to surrender. The sergeant promptly chucked a bomb at him and got a direct hit, but only slightly wounded the Boche. I fully expected to see the officer represented by x!

Railway cuttings are unpleasant neighbours in battle. They are too well shown on the map, and consequently they make excellent data points for Boche gunners: the railway on our second objective was no exception, and the Boche punished it thoroughly. So we got well out in front and consolidated there. We were allowed to dig in comparative peace until two low-flying Boche planes spotted us.

Boche planes received a pretty good run for their money, for the whole brigade was firing at them. And by that time the whole brigade knew how to use their rifles. But they got away, unfortunately; and then the Boche gunners shortened on to us, and we began to suffer casualties which we couldn't afford. Shells sometimes play horrible tricks on their victims.

I remember seeing one of our poor fellows get a direct, or nearly a direct, hit by a 4.2-inch. The body shot up into the air like a rocket, describing a complete parabola. And I saw a tiny speck come down from far above until it was near enough to recognise the head which was following the body!

In the middle of our long halt at the second objective - we stayed there about four hours - we suddenly saw heavy columns of our infantry wending their way across the ridge to their assembly positions near the railway cutting.

The Boche observers must have seen them too, for as one of the battalions crossed the ridge a 5.9-inch opened on them. The third shot found the head of the column, and that third shot must have caused at least thirty casualties.

At a brigade conference held at the cutting to decide on which battalions were to assault in the third attack, Frank Maxwell put the Scottish Rifles on the right, and we were on the left, supported by the Borderers, with what was left of the 12th Royal Scots in brigade reserve. Things were not too bright; for the 9th Division had a big gap on its right. But the wind was in the best quarter, and so the C.R.A.(T.) was able to put down a smoke screen which apparently gave the Boche the impression that we were using gas.

Anyhow the result was that he cleared out in that quarter and enabled the advance to continue.

But we cast many an anxious look to the right rear during the first half of the battle, for we could see with half an eye that things were not going quickly across the river. It was bitterly cold during that advance to our third objective. And we all of us expected to have a pretty tough opposition, for our artillery could not possibly have cut the wire which defended the Boche system round the Point du Jour. But as we advanced the Boche fire appreciably lessened, and as we approached that formidable belt of wire it died down altogether. Even the pill-boxes seemed to show no sign of life.

What could it mean? Some trap, no doubt, and we set our teeth and went for the wire. It was a tough job getting through the wire, even with little or no opposi- tion, and then we saw an inspiriting sight -a mob of Boches hareing away out of the trenches.

It was too much for our fellows: with a wild view - halloa we were after them. It was too much for the Borderers, who raced us for the Point du Jour. What a sight it was when we got there! One could see half the world, and everywhere one looked were fleeing Boches.

Victory, victory! Even far away Monchy

seemed covered with fugitives.

The telephone spoke to Frank Maxwell;

"Are the Boches on the run ?"

"Yes."

"Is cavalry good business?"

"Yes, ten thousand times yes, but it must be done now. Too late to-morrow....Why can't we go on?" And so forth.

Then the 4th Division came through us. They had been marching all day with-out the excitement of battle to buoy them up.

On they went and disappeared into the Blue. What a victory! We had bitten in 3 miles into a strongly defended line held by the Boche's best troops, the Bavarians. On ground of his own choosing we had trounced him well and truly beyond the very shadow of a doubt.

We all thought the war was over - and then a sniper hidden a few yards away in a shell-hole shot one of our best officers! He died - that sniper.

Looking back was almost as fascinating as looking forward. For far below us lay Arras poor, beautiful, mutilated Arras, lying down there in the hollow like a dead swan. Every- one asked his neighbour, "How the devil did the Boche allow us to exist in such a place?"

For it was completely commanded from the Point du Jour, and one could see every move ment in the town. No wonder orders were strict about no movement by day; no wonder I we had been shelled when we skated in fancied security during the winter.

An inspection of the Boche dug-outs showed us that he did himself pretty proud in this sector; but then heavy gunners always do, whatever their tribe.

As the excitement died down I got colder and colder - no coat, and it came on to snow.

At dusk we were relieved by the Seaforths of the 4th Division: but it wasn't much relief, for all sorts of rumours of counter-attacks by the Kaiser in person kept us waiting. It's bad business passing men to the rear when that sort of talk is toward: so we stayed. Then it began to snow, as if nature would blot out our handiwork. "Ugh, the cold," as we shivered in our sweat-begrimed garments.

After some hours I went forward to see if I could get any news. I met a sergeant of the 4th Division coming slowly back with a Blighty. "Yus, they counter-attacked at Fampoux," he answered in response to my query. "And we didn't 'alf put it acrorst them neither." That settled it. "Fall in-home." And we marched back by the light of the moon, for which we had been waiting, to Obermeyer trench, our first objective of the morning.

We got into Boche dug-outs and slept -

how we slept! But the rightful owners of that filthy dug-out prowled and prowled around: we were all of us crawling in lice.'

At this point of total elation, Croft was struck down'...my own worthless carcase began to trouble me; that infernal Trench Fever got me in its grip; the result of exposure and many years in West Africa. In vain I battled against it.'

Carried in the snow, the bearers themselves assumed he would expire due to the '...perisher in the spine' he was suffering. The next day he managed to escape the Field Ambulance and made his way back to the unit, despite clearly in the grips of a severe illness. A fellow Officer ordered him home for 5 days' rest, instead he took 3 days in Hospital and then walked back to the unit who were then at Gavrelle. He was not of a fit state for the action on 3 May and was kept at Brigade HQ when the costly attack went in. The unit left Arras with a bloody nose and next they would prepare for close quarters actions in wooded areas. He also gave comment on two items of note:

'The writer has had some experience of wood fighting in West Africa, and on one occasion at least he is sorry that he did not use the methods quoted at wearisome length above.

For a poisoned arrow in the hand, at four yards, without even a sight of the man who did the deed, is a high payment for experience, even valuable experience of that nature. Believe me, as one who knows the bush pretty well, firing with the rifle tucked well under the arm-pit as one advances, has much to recommend it in bush fighting. And as one doesn't hold the opinion that the gentle savage will welcome the League of Nations just yet, it is hoped that the above tips regarding the discomfiture of that slippery customer may be of use.

I had a sporting bet with my battalion one Sunday afternoon when it became obvious that they were getting a bit too beany. We organised a paper-chase, and I offered a franc to every man who could catch me I was one of the hares.

The whole battalion had to turn out, and, thanks to a well-organised system of mounted officers, the whole battalion had to do the course. Apparently the men got restive after half the time allotted for our start had gone, and suddenly B Company made a dash for the gate they were standing in a field. Don Company, not to be outdone, swept over the hedge, and the whole pack went down the village in full cry on a breast-high scent. And as I toiled along the hot and dusty road carrying, in addition to my own bag, the bag of a hare who had dropped out, I suddenly heard this shouting mass running almost to view. Luckily we soon gained the shelter of the woods, and after that we shook them off, coming in at no cost to my privy purse.'

Returned to the trenches near Havrincourt Wood, Croft was not to remain there for long, for higher command called. He was withdrawn from the line on 13 September 1917. The following day he was made Brigadier-General in the 61st Division but was duly given command of the 27th Brigade in his beloved 9th Division a week later. On 20 September the Brigade won its first Victoria Cross at Frezenburg Ridge, when remarkable bravery was displayed by Captain Harry Reynolds:

'...I saw his kit afterwards; every part of him was punctured with bullet holes - his clothes I mean, for the Almighty was merciful to Reynolds that day, and he had not received a scratch.'

The remaining months saw Croft find his feet with a greater command and he led the Division through the actions at Ypres, including at Passchendaele (12 October) and St Julien. On finally settling down as the events begin to subside, Croft got a telegram:

'On getting back to our very comfortable dug-out in the canal bank I found a wire telling me of the arrival of a daughter, born during the Batte. She was asking to be called Ypres, absolutely asking for it, but with great magnanimity I let her off!'

They saw out the year in the costal sector held by the British, being '...bombed as we entrained at Irish Farm and again at Poperinghe', but were able to enjoy the relative quiet around Dunkirk. Keeping busy in the winter months, his unit were again in the thick of things when the German Spring Offensive was launched on 21 March 1918, for which the citation for his Third D.S.O. clearly reference. His book makes a smart reference:

'For in spite of what our theorists may lay down concerning the necessity of hanging on to the last, even though surrounded, it is quite another thing to stay where you are when you can see an irruption of field-grey crowding round your flank as you manfully struggle against the odds in front.

It doesn't take a Napoleon to guess the result of staying too long. Most of us have made sand-castles, on which, when completed, we have proudly stood watching the tide lap round us. But there came a time when we had to go, not on account of the castle subsiding, for that still had many inches of safety; but because the tide had crept so far in behind us that we must jump or get our feet wet. Apply all this to the retreat and you have the point of view of the poor old Fifth Army who, like the sand-castle in the tide, were simply overwhelmed by force of numbers.'

Croft was back onto the 'Bloody Salient' and was lucky to escape when an 8-inch shell made a direct hit at Scherpenberg. He was having a shave rather than taking breakfast with his comrades and that saved his life. The Division was also beginning the push-back against the losses of the Spring Offensive and were causing the enemy problems. Cracks were starting to tell and his charges were delivering damaging blows. Furthermore, the actions at Watou, when the French re-took Scherpenberg, Mont Rouge & Mont Noir further stunted any enemy momentum. The Division were then relieved and had a message from Sir Douglas Haig and Marshal Foch to thank the entire 9th Division for their work. It stated '...that it was due to their magnificent resistance that the Allies had not been forced to withdraw to a line in rear of St Omer and to flood the country in front of St Omer.

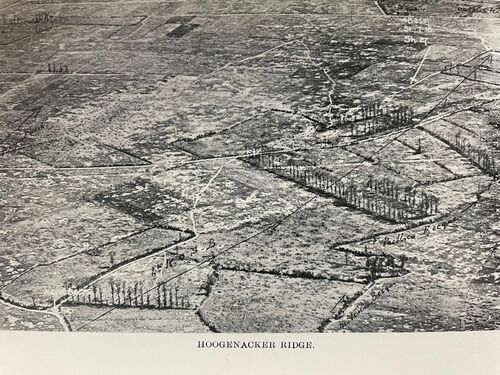

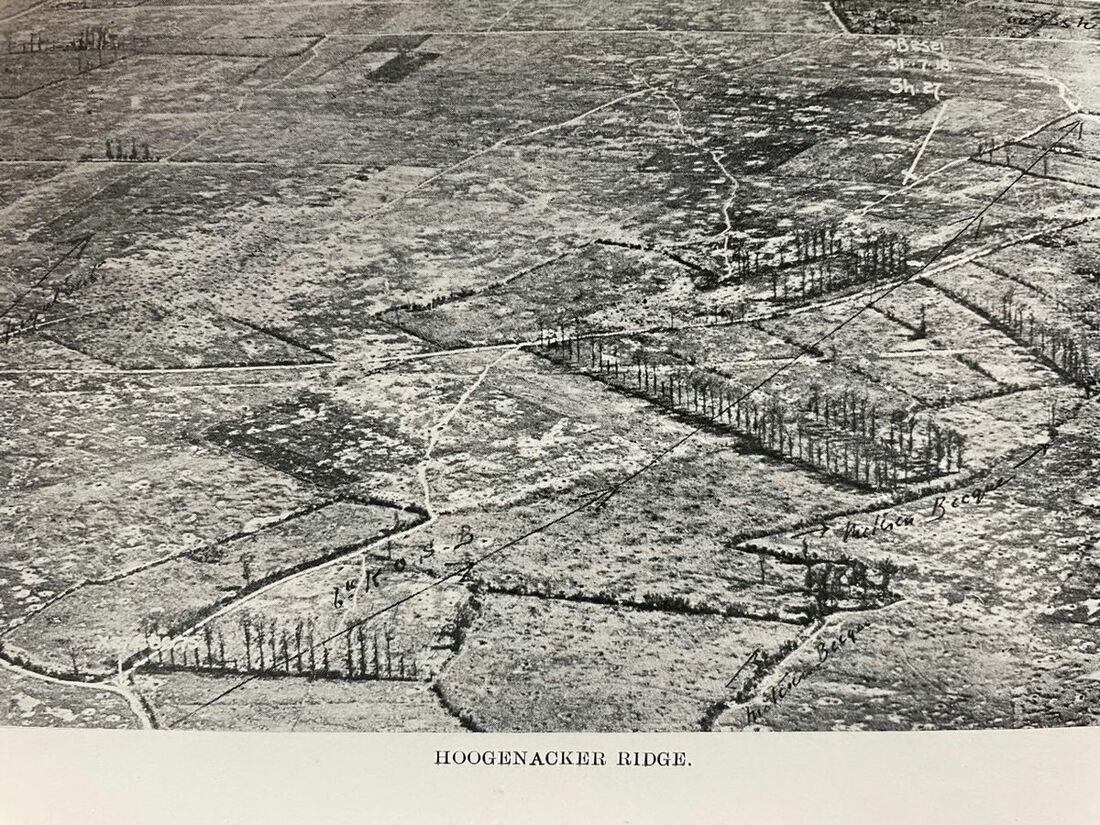

Their next posting was in the Meteren section, with the Australians to the right flank and the French to the left flank. It was cramped and a relatively stationary sector but their action at the Battle of Meteren in July 1918 captured valuable ammunition. Further action took place on Hoogenacker Ridge and then on Kit-Kat-Anzac-Broodseinde Ridge. That latter action got underway on 28 September and again cavalry was deployed to fine effect. The German Army was beginning to fall and the Division advanced across Hill 41 and latterly at Ledeghem in early October 1918. His cool command under fire was again testing at the crossing of the Lys, when several units found themselves under a hail of fire and putting up the SOS call. With careful management and a fine handling of the situation, the vital bridgehead was maintained with supplies and support ensuring the victory. It was for these actions that Croft earned his historic Third Bar (Fourth Award) to his Decoration. The final moments of the Great War and the reflections of Croft are best said by the man himself, thus Chapter XV is reproduced in full:

'By a happy coincidence "Blue Bonnets" is the regimental march of all three battalions of the Lowland Brigade; consequently it was adopted as our brigade march-past on those rare occasions when we indulged in ceremonial.

Such an occasion occurred during the first week in November when we were inspected by H.M. the King of the Belgians. All things considered it was a highly satisfactory turn-out; especially so on the part of the gunners, who had but just come out of the line. It was a treat to watch them, as we waited our turn to go by; for they marched past like a solid wall. Then came the Highlanders, swinging by in their kilts - what a show a kilt does make on a ceremonial parade! - then the Lowlanders; and lastly the 28th Brigade. A great crowd of Americans watched the performance, and their remarks, which were quite audible, were very much to the point.

Afterwards the King, accompanied by his Queen, both riding, made a speech to the senior officers, in which he thanked us for all we had done, and so on.

And all the time the rain splashed down on the aerodrome on which the parade was held, marring what would otherwise have been a magnificent pageant.

For it is not every day that one sees an entire division, horse, foot, and all assembled together in one place; guns, especially a division which has just come out of battle. Our divisional commander afterwards gave our divisional badge - everyone in the division wore a little white metal thistle on blue cloth on either shoulder - to the Queen, who promptly made a brooch of it. So far as we know the only other lady who has been given this badge is the Princess Mary, who received it from the Lowland Brigade on becoming Colonel of the Royal Scots.

Possibly, however, there may have been other presentations, to judge from the number of deficiencies of the badge on the part of returning leave men!

We were billeted at this time in Cuerne of bitter memory, and we soon became uncommonly comfortable. The extraordinary thing was that our Lowlanders could carry on a conversation with these Flemings, for many words were common to both races: not that we liked the Flemings particularly, for they are not half such good fellows as the Walloons who live for the most part on the east side of Belgium, and who showed their appreciation of us as we marched through their country later on.

Then came the Armistice like a bolt from the blue. None of us had any idea that the end was so near, but we all knew that the Higher Command was getting ready to administer the absolute final punch which would have caused an utter debacle. So we felt that it was a pity he didn't get his punch, the Boche.

And, since coming into Germany, we have found no cause to alter our opinion, for he has been lately talking very big about his unbeaten heroes.

Shortly after the Armistice was declared we, together with the 29th Division, were selected for the post of honour - to be nothing less than the spearhead of the British Army during its advance to the Rhine; and later these two divisions and the Canadians were selected to hold the bridgehead. So not only were we the only Scottish Division but the only Service Division in the British Army of Occupation.

On 7th December, the Lowland Brigade crossed the border to the tune of Blue Bonnets. As we stood at the frontier post and watched the old brigade swing by we could not help thinking of all those gallant souls who had gone west, owing to whose gallantry on many a stricken field we were still able, at the end of the war, to maintain our high standard of efficiency. For we always felt that those who had fallen in action were still with us in spirit, and that it was by reason of their presence that we had always been able, under the most trying conditions, to do our duty. It is a good old simple belief which has carried us right through the war.

In war, in order to stick it out day after day, winter and summer, in face of set-backs and disasters, religion is essential. This fact has been proved again and again in all wars. To quote but a few cases:

What made the warriors of Saladin invincible? Their religion.

What made the Ironsides of Cromwell the terror of Europe?

What made Fuzzy Wuzzy break a British square?

And, in the present war, why were the Scottish troops the best fighting material in the world? The same answer - Religion. Whether a man be a Ghazi or a Gloucester, a Hottentot or a Highlander, provided he is soaked with religious fervour which makes him forgetful of self, ready to offer himself willingly as a sacrifice, taking no count of his body as compared with his immortal soul, that man is invincible in battle, and an army of such men can rule the world.

But this religion must be no affair of mushroom growth-the religion which comes to a man who hears a crump for the first time. No, no; it must be ingrained; taught from babyhood.

Oh, make no mistake about it, religion is the mainspring of the Happy Warrior.

For those who have lost their dearest, to whom life must be a blank, it may possibly be some slight comfort to know how we all felt in the Lowland Brigade to those who had died with us. And it was the custom, in at least one battalion, after every battle, for the battalion to parade as strong as possible, in close column.

Then the buglers played the Last Post while the battalion presented arms.

There is little more to tell. But a saying of General Foy's, in his history of the Peninsular War, may be of interest. He has said, writing nearly a century ago, that the condition of the British soldier never retrogrades; but that, retaining all the good qualities that his pre-decessors had acquired, he superadds to these, from generation to generation, whatever of improvement each may have happened to produce. The history of the British Army in this last great war fully bears out the assertion of the French writer.

And now here we are in the heart of our enemies. We do not understand them, neither do we appreciate their manners, or lack of manners, as the following two incidents will show.

A padre -O- as a matter of fact - was coming back from Cologne by train. The carriage was crowded and O offered his

seat to a lady, who gladly accepted it. On getting out at her destination, instead of taking it for granted that O would resume his seat, she went out of her way to offer the place to one of her own countrymen who was also standing. O, who understood German perfectly, looked at the German; the German looked at O, and remarked that he preferred to stand. So much for their manners!

A funeral was passing one of our guards.

The sentry came to attention and saluted the funeral. A well-dressed man walked up to the sentry and remarked in English :-

"You are our enemies, but your manners are perfect."

And that is the motto of the British Army in Germany. Because the Hun is a Hun, that is no reason why we should copy him.'

So it was, that Croft ended the Great War with a C.M.G. to go with his Four D.S.O.'s and the plethora of 'mentions' showered down upon him. Croft had applied for his 1914 Star and clasp in December 1917 and the Medals in 1921.

Returned home, he went up to Staff College in 1919 and joined the 2nd Battalion, Tank Corps in February 1920. In October 1923 he was made Colonel of the Royal Tank Corps in India and served as an instructor at Senior Officers' School in 1927. He was made Commandant of the Royal Tanks Corps Centre from 1929-31.

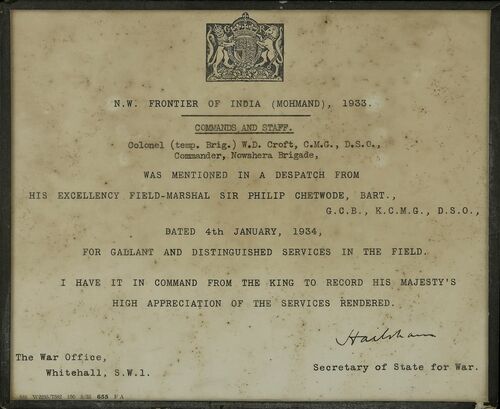

Posted as temporary Brigadier and commander of the Nowshera Brigade in India in 1931, this saw him share in the Mohmand Operations in 1933. He added a final 'mention' for good measure, before retiring in 1934 and was conferred the C.B. upon retirement. Living at The Anchorage, Mawnan, Falmouth, Croft called upon his old friend Winston Churchill for an active posting at the outbreak of the Second World War. By that time having just turned sixty, it was not meant to be and he was instead made Group Commander of the West Cornwall Home Guard. Latterly giving many years of service to the Scouts Association in Cornwall, he was conferred with their highest honour, the Silver Fox Award in 1951 by the Chief Scout Thomas Corbett, 2nd Baron Rowallan. The Brigadier-General died on 14 July 1968.

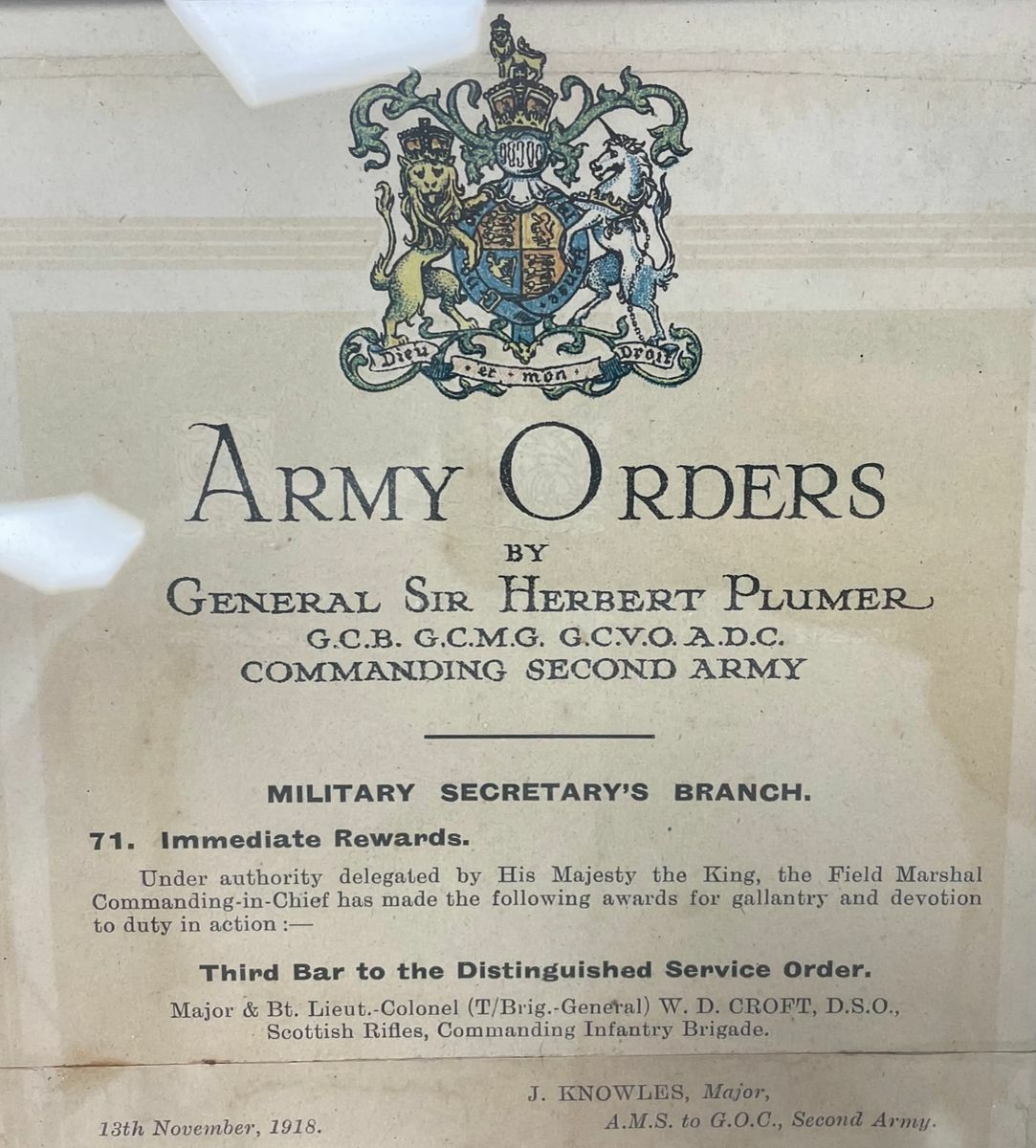

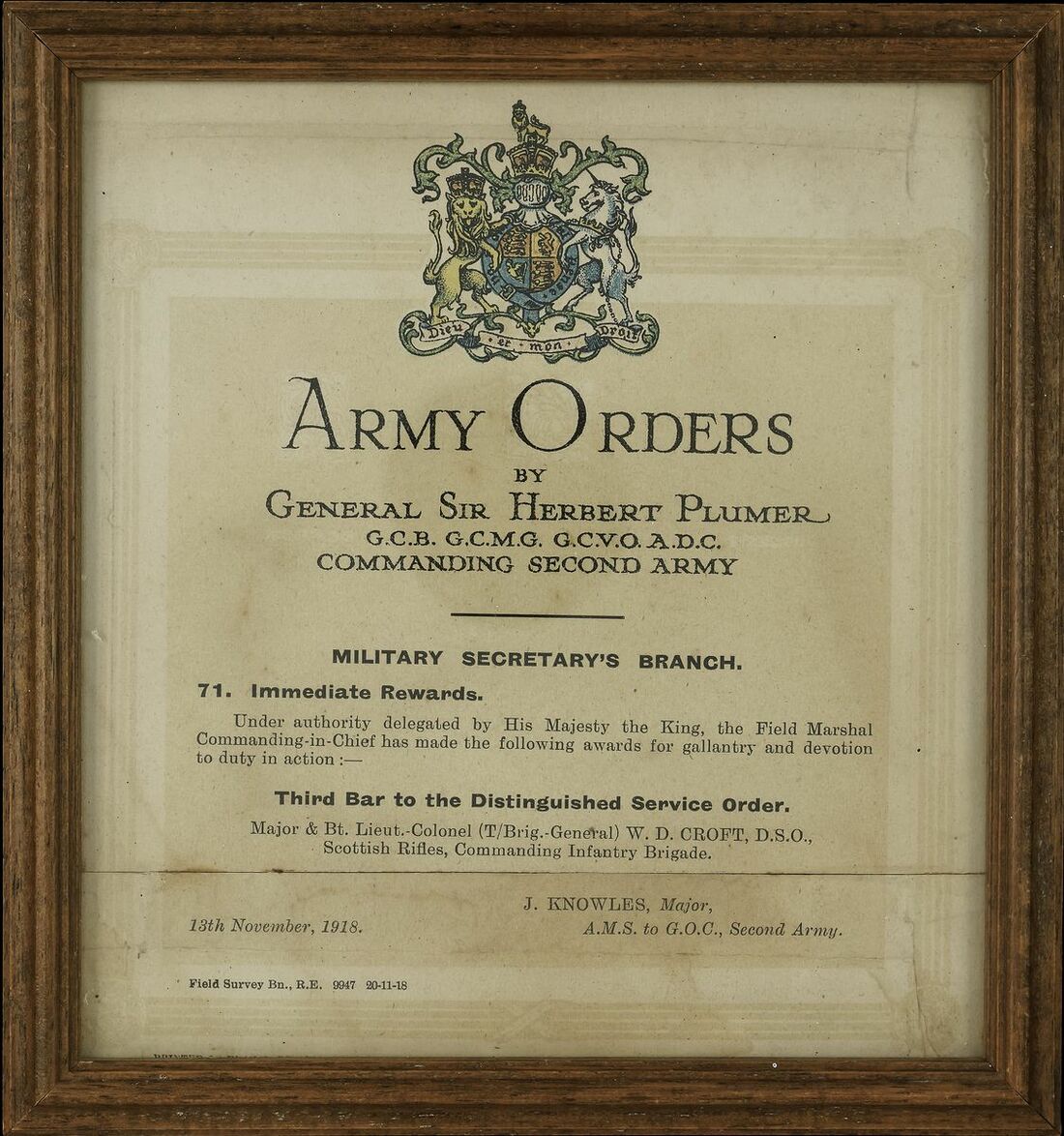

Sold together with Bestowal Document for the C.B., Legion of Honour, Army Orders for the Fourth D.S.O., six of his Great War M.I.D. certificates, his Mohmand M.I.D. Certificate, this last from Field Marshal Sir Philip Chetwode, Bt., two portrait photographs by Bustin, Hereford and the copy of Three Years with the 9th (Scottish) Division (1st Reprint, December 1919) he presented to his wife, Esme, which has since passed down the family. This edition includes several pasted articles and notes, presumably from the author.

For his miniature dress medals, please see Lot 328. For his sword, please see Lot 132. For his uniform riband bar, please see Lot 133.

Subject to 20% VAT on Buyer’s Premium. For more information please view Terms and Conditions for Buyers.

Sold for

£42,000

Starting price

£12000