Auction: 23003 - Orders, Decorations and Medals

Lot: 238

Sold by Order of a Direct Descendant

'At 0930 it was, "All hands to action-stations". My action-station was in the ship's Chapel; I think it was with two cooks and three Supply Ratings, in the capstan flat forward of "A" Turret, a small place with only about eight chairs.

Then it was up anchor and we steamed up river for about a quarter hour and stopped. Nothing had happened so we decided to proceed again, and all hell broke loose.

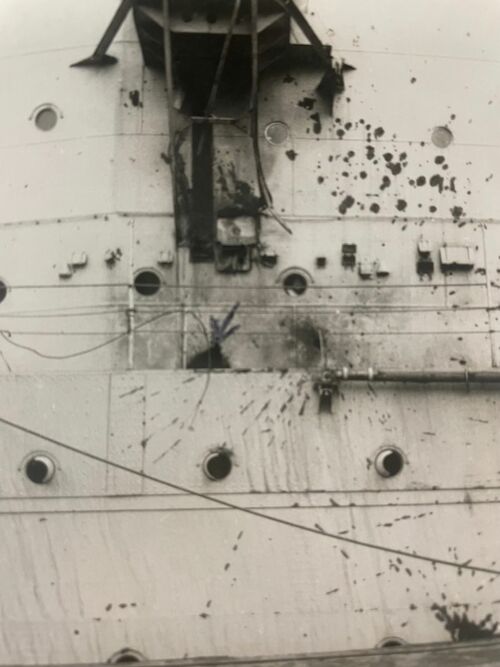

The mobile guns had caught up with us, and where possible we answered their fire power. We knew that the bridge was being hit and the turret above us came in for its share, but we had no idea how much damage was being done. The fan light in the Chapel was shattered; this was like a porthole in the deck-head, made of glass about two inches thick, but strangely it did not splinter.

Enough to say that it was frightening. One of the cooks said "Bandy, can we have a smoke?" I reminded him that we were in Church, but he said that he did not think that Jesus Christ would mind. So we all lit up....

In the dim light I saw someone on the deck. He touched my leg. I spoke to him and he told me his leg was gone. It was now getting unbearable down there so I went to the hatch, and they passed me a Neal-Robinson stretcher. I felt his leg but could not see: I got two handkerchiefs and tied them together and put them around his leg. I got a piece of wood twisted it round, and put the end of the wood under his belt. I got him up the hatch, took him to the PO's Mess and laid him on the table. I had a word with him and he was still conscious. I told him to wiggle his toes: he did, or thought he did and then passed out.'

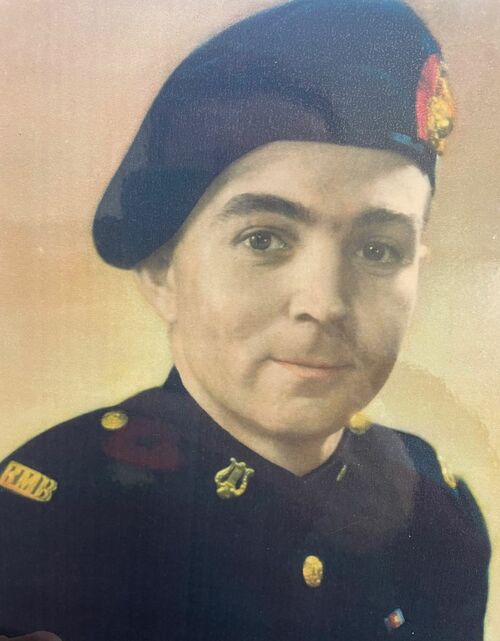

A few moments of terror recalled by Bandmaster Fred Harwood, Royal Marines

The unique 'Yangtze incident 1949' D.S.M. group of twelve awarded to Bandmaster F. G. Harwood, Royal Marines

During a devoted career of three decades in the service of the Royal Marines Band, Harwood observed a remarkable array of action; this began with playing at the funerals of the German seaman killed when the Deutschlandwas bombed during the Spanish Civil War

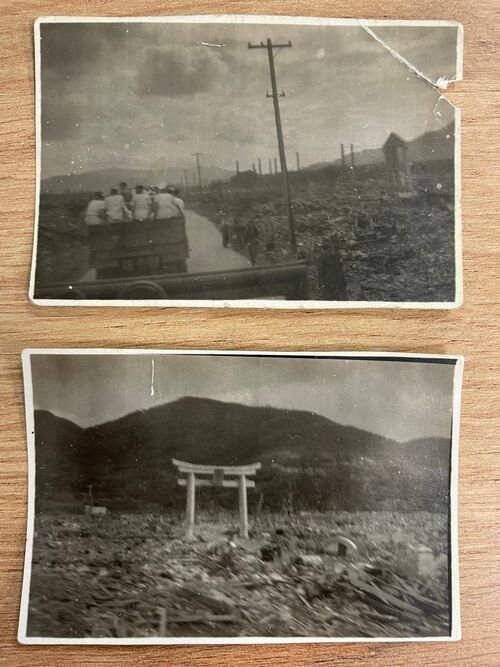

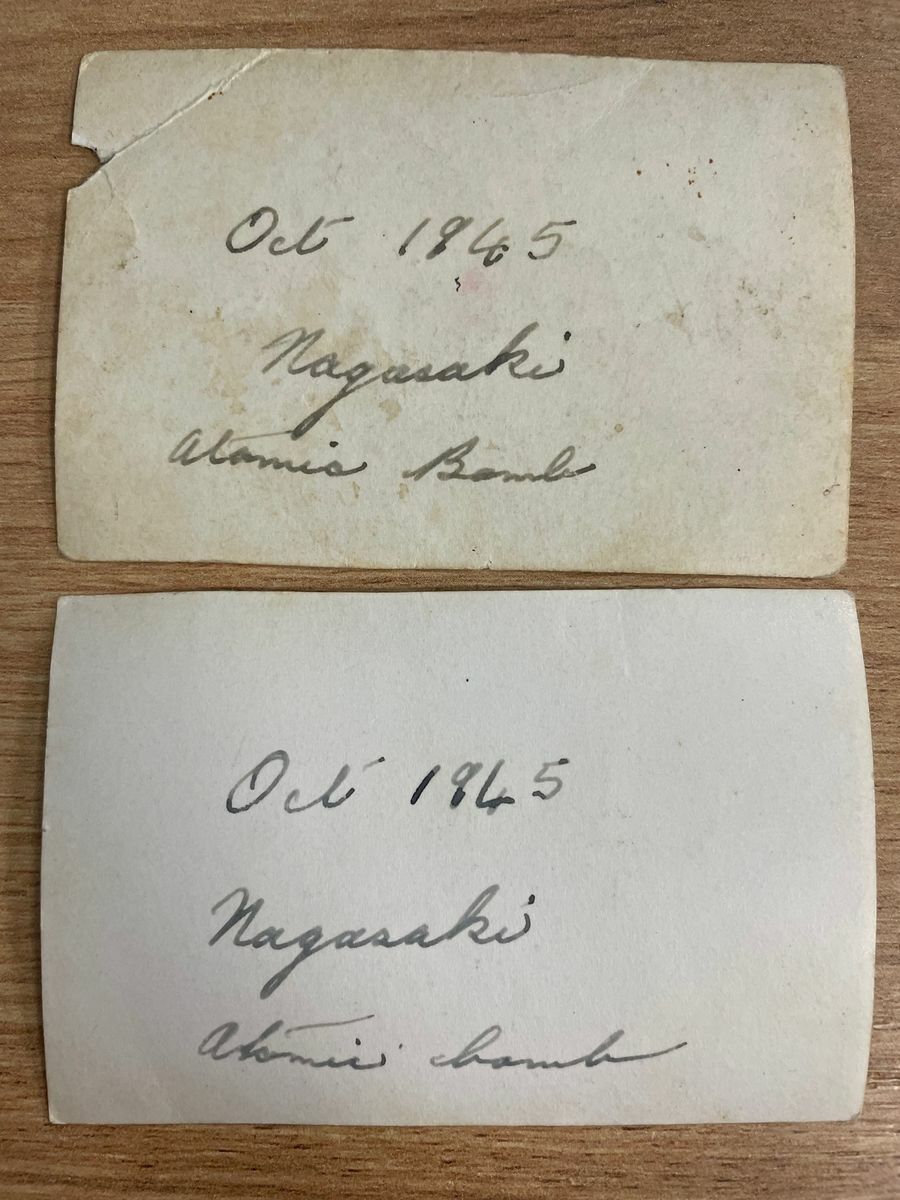

During the Second World War he was aboard the Norfolk for the famed action with the Bismarck, before going on Arctic & Malta Convoys, sharing in Operation Torch and thence serving on Swiftsure in the Pacific, being a witness to the devastation at Nagasaki in the aftermath of the dropping of the Atomic Bomb - besides capturing photographs of the harrowing scene

His finest hours came during the legendary Yangtze incident - for which he left a detailed unpublished account - when he commanded the Stretcher-Bearer Parties of London, transferred the casualties of Consort, in doing so inspiring and comforting the wounded and dying, besides assisting the Surgeons in their grisly work; Harwood worked tirelessly for some sixty hours without rest and was rewarded with the only D.S.M. to the Royal Marines for the action

Distinguished Service Medal, G.VI.R. (Bndr. F. G. Harwood. R.M.B. X.368. R.M.); 1939-45 Star; Atlantic Star; Arctic Star; Africa Star, copy clasp, North Africa 1942-43; Pacific Star; Defence and War Medals 1939-45; Naval General Service 1915-62, 1 clasp, Yangtze 1949 (RMB/X 368 F. G. Harwood. Bandmtr, R.M.); Royal Navy L.S. & G.C., G.VI.R. (RMB.X.368 F. G. Harwood. Band. Sgt. R.M.B.); The Order of St John of Jerusalem, Service Medal; Malta Commemorative 1992, contact marks from Stars, very fine (12)

Just 7 D.S.M.'s awarded for the Yangtze incident, 6 awards to the Royal Navy and this a unique award to the Royal Marines.

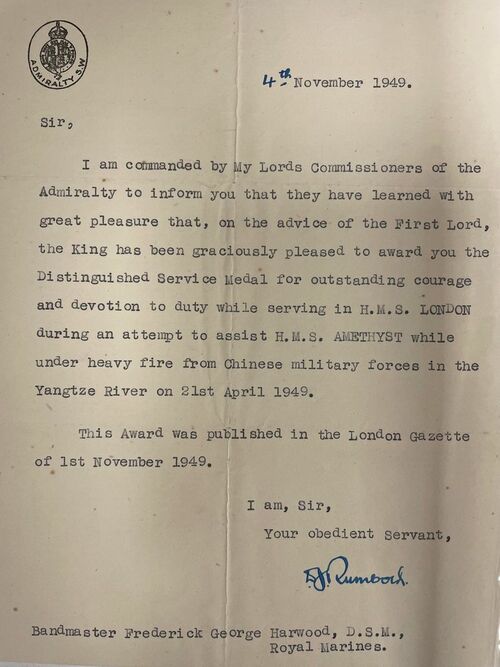

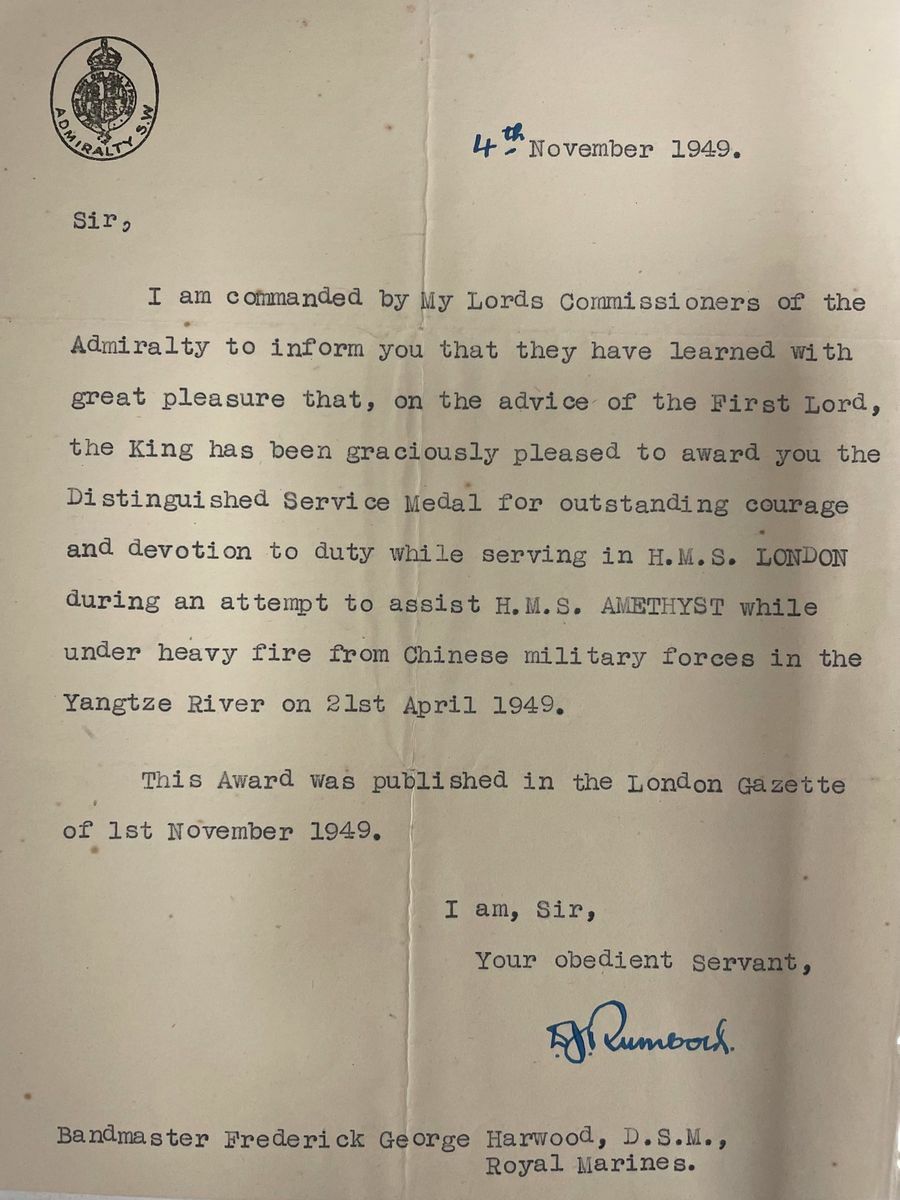

D.S.M. London Gazette 1 November 1949:

'For outstanding courage and devotion to duty while serving in HM Ships London, Consort and Black Swan during their attempts to assist Amethyst while under very heavy gun fire on 21-21 April 1949.

The original Recommendation states:

'Harwood was in charge of the Royal Marine Band stretcher-parties and worked all the night of 20-21 April supervising in the removal of Consort's casualties to London and giving encouragement and comfort to them. On 21 April, during the action, he worked continuously among the wounded in various places indifferent to danger, giving first aid and comfort and displaying marked initiative and level headedness. This he continued to do all through the night for 21-22 April. He then went with the wounded to the US Hospital Ship Repose and remained with them until they were settled in, not returning until that evening. He then had no sleep for 60 hours. His effect on morale was quite outstanding.'

Frederick George Harwood was born at St Peters, Plymouth, Devon on 20 October 1915. Young Harwood enrolled in the Plymouth Company, Royal Marines Cadet Corps on 7 October 1924 whilst also being at school. As part of the Cadet Corps, he learned the bugle and from there on in, the only aim in life was to become a Bugler in the Royal Marines. In his own words:

'The papers were brought for my father to sign and he signed me away for 15 years and 348 days. For good or bad I was in the service until I was 30 years of age.'

Discharged from the Cadet Corps on 6 November 1929, he joined the Royal Marines as a Band Boy, going up to the Royal Navy School of Music. Remaining there until 12 October 1932 he thence joined Berwick, being promoted Musician on 20 October 1933. He went with her on her tour of the Far East, that saw them go into Wantow. An amusing incident took place:

'The Band went on a trip to the Great Wall of China, we were taken there by a mule truck on lines. We went on top of the wall, a very rough top not like I've since seen on TV....Charlie Patridge said "while we are here piss over the top and what's more you'll come back again."

It's great to say I pissed over the Great Wall of China and I did return twice more.'

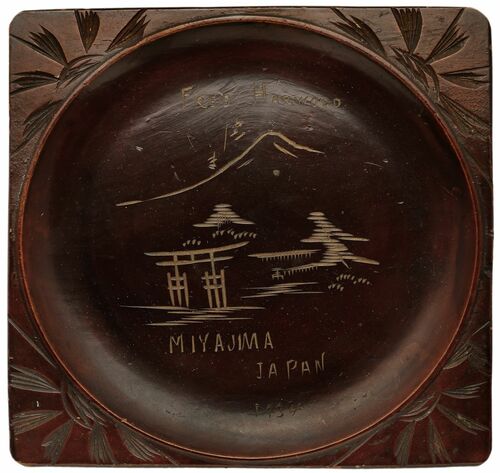

The tour also included a visit to Nagasaki. He recalled:

'I will never forget that. The harbour had a narrow entrance but we went in stern first. We were told that this was to avoid going past the dockyard to see the building of ships. They were friendly people but my next visit there was to be totally different - more about that later.'

During the 1930's he had various postings with the School of Music and afloat aboard St Vincent and Devonshire. It was in this period that the Spanish Civil War was in full flow. The Deutschland (later renamed Lützow) was officially designated an ‘armoured ship’ or ‘heavy cruiser’ but was actually a light battlecruiser, popularly referred to at the time as a ‘pocket battleship’. During the Spanish Civil War the ship was deployed along the Spanish coast, ostensibly as a part of an international force charged with keeping the sea lanes open but actually supporting Franco and the Spanish ‘Nationalists’. On 29 May 1937, the ship was at anchor off Ibiza in the Balearic Islands, when she was bombed by two ‘Republican’ bombers. The aircraft dropped 12 bombs, two of which hit - one of which hit the unprotected mess quarters in the forward part of the ship causing heavy casualties. Early reports listed 23 dead, 19 severely wounded and 30 plus less seriously wounded. Needing specialist facilities to treat many of the wounded, the ship made for nearby Gibraltar. As it was, Harwood found himself there and he formed part of the two massed bands, their drums draped in black, that played at the funerals for the German seamen.

Just before the outbreak of the Second World War, Harwood joined the books of Norfolk, in what would be the start of an action-packed period. Quickly deployed in pursuit of the Gneisenau, Scharnhorst and Admiral Scheer, Norfolk was damaged by the detonation of 'near-miss torpedoes' from the U-47 and made for repairs at Belfast. Re-joining the Home Fleet at Scapa Flow, he had the opportunity to perform in this period:

'Every time the patrol finished it was back to Scapa Flow; a massive fleet was massed there. We occasionally went ashore to the canteen for massed band practise. Tommy Lang was the WO Bandmaster for the fleet and we flogged Rachmalinof's piano concerto. In the end we had two great musicians arrive, the pianist Pussinoff and the violinist Yehudi Menhuin. We performed a concert in which Pussinoff plated Rachmalinoff's piano concerto. This was of course the reason we had practised so much. We had one rehearsal with him before the concert. He controlled everyone but we took great pride in saying that we have played in that concert...As you can see at the beginning of the War we still used our musical instruments.'

She sustained further damage in a heavy air raid on 16 March 1940, as Harwood recalls:

'About the second week, a German bomber came over Scapa; no shots were fired at it and it dropped a bomb square on the stern of Norfolk - quite a bang - it went right through the Midshipman's flat. When the mess was cleared away we had to put ropes up to stop us falling in the water. 48hrs later we went to sea.'

Promoted Band Corporal on 1 April 1940, Harwood went to Deal where a new band was formed, also being called upon to ferry the sick and wounded from Dunkirk from Deal to Folkestone. Then it was back to sea with Norfolk from 14 June 1940-25 August 1941. In that period she shared in the Battle of the Denmark straight and also spotted the mighty Bismarck:

'All the TS and guns in full readiness. It was pouring with rain, blowing a gale and through all this a ship was sighted. We were signalling "WELL DONE RODNEY - GLAD TO SEE US!". Captain Ruffa in the Director said, "IT'S THE BISMARK!".

One great blast from the guns that could line up on us so we swung around about 180 degrees, lost every cup and saucer aboard and everything went over as were now firing our after turrets.

Soon the heavens lit up, the big ships firing their 16 inch guns. We returned and joined in again. I had a running commentary from Captain Ruffe. She was still firing but less and less coming back there were fires everywhere on board her and they were working as hard as they could to try and keep the ship going. The weather that morning was the worst I had ever seen.

All our torpedoes fired (8) - only one hit. The Bismarck was listing by now and we were told to disengage and proceed back to the Clyde right up through the Irish Sea.'

Returned ashore, Harwood was put to work on a tour of music engagements, fine-tuning his skills with the flute and French horn, quite the contrast to his previous posting. They played around the country and performed with Walter Widdop, Ann Zeeglar and Webster Booth.

Returned for duties with the aircraft carrier Argus on 30 July 1942, Harwood remained with her until 16 April 1943. This period saw Argus assist in the Malta Convoys and in November 1942 she was assigned to the Eastern Naval Task Force that invaded Algiers, during the 'Torch' landings with some 18 Supermarine Seafires of No. 880 Squadron aboard. The ship was hit by a bomb on 10 November that killed four men. Harwood saw it all:

'That evening about 1700hrs the dive bombers came. I was on the wing bridge and the Captain was on the flight deck looking up at the planes. When he saw the bombs leaving them, it was change course. There were lots of near misses, big bangs and shrapnel flying everywhere. Then Captain Phillips had a better idea, laying back in a deck chair saying '10 to port, centre wheel hard to starboard etc.'. The master piece of all down went the lift to the hanger floor, smoke bombs set alight then slow flares, lift came half way up, smoke and red flares mixed a lovely sight, up a little more, Stuka dive bombers satisfied that we were sinking, no more bombs wasted.

Later that evening I saw phosphorous crossing our bow, shouted torpedo coming in starboard Sir, Catain shouted "you are too bloody late, it passed hard to port!"'

Thus his tour with the vessel closed out, with further postings to Bristol from 20 May-16 December 1943. Whilst there, his wife was also posted to the NAAFI and with Russia coming into the Second World War, the Band often played the 'Red Flag', which '...the lads loved marching to.'

Posted to Swiftsure on 2 June 1944, Harwood would see action in the Pacific theatre for the conclusion of the Second World War. She participated in the Okinawa Campaign of March-May 1945 and in June took part in the carrier raid on Truk:

'Our journey took us to Truk in the Pacific, which was the biggest natural harbour in the world, Indomitable was the carrier. We went inside the inner harbour to bombard, and after the first broadside, the split-pin fell out of the drive in the transmission, then it was all guns controlled by the Blue Control Position, we took over, did our job, go out and left the planes to do their best. During this attack I had a signal that my mother was dead and had been buried.

The next phase was off the coast of Japan, no opposition now; they had very little petrol, no food, no ships coming out, so our only opposition was Kamikazes. In this particular action there were seven of them, only enough petrol for the action, then die at sea, no undercarriage.

They set for our carriers twice, coming from the stern and dropping a bomb. It slipped through the flight deck like a flat stone skimming across the water, over the bow and exploding. This happened twice, but the third time one came from the port side which hit the bridge and superstructure, she reduced her speed to nine knots, we stayed with her, and then when her speed increased we caught up with the fleet.'

Next she went into Hong Kong and at this time was the flagship of the British Pacific Cruiser Squadron. Thus she was selected by Admiral Cecil Harcourt to hoist his flag for the Japanese surrender. Despite the surrender, there was still work to be done:

'Next day I was sent ashore to look after the Law Courts and Museum, two days after I was stationed at Repulse Bay Hotel with two Royal Marines who all had Tommy guns. We were not far from Stanley Prison Camp, we saw some terrible sights. Sikhs with both hands cut off by the Japanese and had leather cups over the ends....We moved south to Nagasaki early on 18 October and thanks to the co-operation of the US Marines, everybody got the opportunity to visit what was left of the City. Pictures and articles in the newspaper had taught us what to expect, but nevertheless the sight of such complete devastation came as an unpleasant shock to many of us. The newspapers had in no way exaggerated the damage; only a few twisted buildings stood amongst the acres of rubble, and although a few roads had been cleared the rest was as it had falled, with charred bones, and even skulls amongst the rubble. Here and there amongst the wrecked building could be seen a torpedo warhead and other evidence of war plants, but the presence of so many small, unbroken ornaments and china were amongst the rubble had been small Japanese homes. Most of us returned on board from our visit in an extremely depressed state of mind.'

Harwood captured photographs of that dreadful sight and was advanced Temporary Bandmaster 2nd Class on 18 September 1945. Returned home he went up to Lympstone and the Royal Marines Band Infantry Training Centre, confirmed Bandmaster 2nd Class on 7 December 1945 and Band Sergeant on 31 October 1947. His L.S. & G.C. Medal was issued on 20 October 1948. Harwood joined London from the Royal Navy School of Music on 12 October 1948 and was made Bandmaster on 31 March 1949. No finer account of what followed can be offered than by the man himself. A copy of his full, unpublished memories of the events are thus reproduced in full for the first time:

'A first-hand account, by Bandmaster F G Harwood DSM., of the valiant attempt, under heavy fire, by the cruiser HMS LONDON to rescue the disabled British Sloop HMS AMETHYST from under the guns of the Chinese Communist shore batteries on the River Yangtse.

HMS LONDON was to have gone to Shanghai for St George's day, though it was known that the communists were advancing fast on Shanghai, but the plans were still going ahead, mainly I suppose to show the Flag and, if necessary, to be some form of security for the British nationals in the area. On board, preparations were being made for this event.

On 17th April I was told by the Captain Royal Marines that Admiral Madden and his Staff were coming aboard, but with all the activity going on, it seemed that it was far more than a visit to Shanghai for St George's Day.

We stored ship, fuelled and took on board ammunition; lorries and land rovers were on the upper deck, so it became apparent that the situation was getting worse. Early on the 18th we sailed and outside the harbour we increased speed to thirty knots. Our bow went up, and the stern tucked down in the water; twelve thousand tones travelling at such speed must have been an impressive sight.

On the afternoon of the 20th the captain cleared lower deck, and told us that the AMETHYST had been attacked and that she was aground on the south bank of the Whang-Poo River. Permission had already been granted for HMS AMETHYST and HMS CONSORT to use the river and exchange duties as the guard ship at Nanking, so why HMS AMETHYST was fired on we may never know.

CONSORT left Nanking, hoping to assist AMETHYST, but after three attempts, heavy damage and loss of life, she had to disengage. Our ship now became very busy. Issuing anti-flash gear, fusing shells, preparing the ship for action, and soon we were in a high state of readiness.

We steamed right up to the Nationalist anchorage, right in the centre of the fast-running river, Communists on our starboard side and Nationalists on the port side. Then it was down awnings, stow them away and take all electric lights down as these had been rigged up ready for illuminating the ship on St George's Day.

At about 2000 HMS CONSORT came down the river, did a 180 degree turn, and tied up alongside LONDON, on our port side. As soon as HMS CONSORT was secured, her Captain came aboard, met by Admiral Madden in the port waist. HMS BLACK SWAN had secured on our starboard side; her Captain came aboard as well, and all the commanding officers went below to the Admiral's quarters. Incidentally, HMS BLACK SWAN had come from Shanghai.

Now it became our turn. The band had mustered in the port waist to bring the wounded aboard and we had to rig a gangway from our upper deck to the top of the destroyer's bridge. The worst cases brought aboard, and Doctor Taylor got down to work. Our young doctor and two SBA's went aboard the destroyer and stayed with the SBPO.

At about 0500 we finished making them comfortable, and it was time to replace the dressings we had used and get the wounded back aboard CONSORT. How different she looked, as our tradesmen had welded plates over the holes and made her look quite different.

One of her crew did not go back on board; he was their wireless operator. The wireless office underneath the bridge had been hit, and he was burned from under the chin to his toes. He just lay on his back in the cot, eyes moving but not speaking, and it looked as though he was going to do the journey again.

Our ship's painter had painted Union Jacks on canvas and draped them over the side: he also painted a large one to go over the front of the bridge. Then it was goodbye to CONSORT, and she steamed off to Shanghai.

When it was light we could see the communist's on our starboard side, so if there was any trouble it would be this side of the ship that would catch it. The Admiral had tried to contact the Communist Commander but all to no avail, so in the end, he alone had to make the decision.

Our Captain spoke to the ship's Company, and told us that we were going to try to bring the AMETHYST down river. We hoped there would be no trouble but if there was, he knew that we would all give of our best.

The band had no official action-stations, so they all volunteered for various duties; some went to Damage Control Stations, others to Shell Handling. Cordite Rooms. 4 inch Ready-use Lockers, and myself to First Aid.

At 0930 it was, "All hands to action-stations". My action-station was in the ship's Chapel; I think it was with two cooks and three supply ratings, in the capstan flat forward of "A" Turret, a small place with only about eight chairs.

Then it was up anchor and we steamed up river for about a quarter hour and stopped. Nothing had happened so we decided to proceed again, and all hell broke loose.

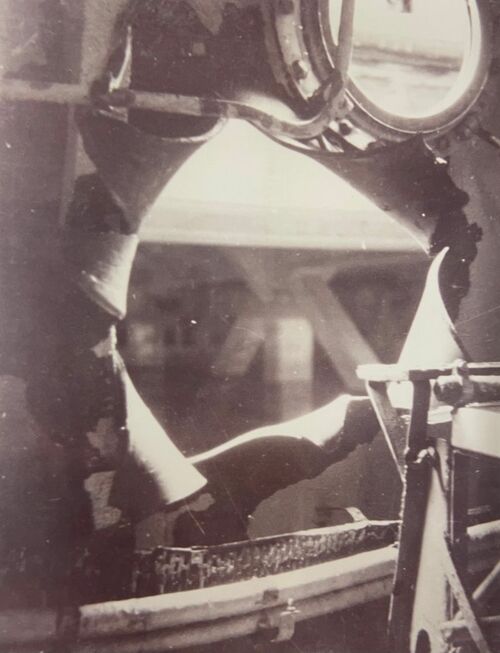

The mobile guns had caught up with us, and where possible we answered their fire power. We knew that the bridge was being hit and the turret above us came in for its share, but we had no idea how much damage was being done. The fan light in the Chapel was shattered; this was like a porthole in the deck-head, made of glass about two inches thick, but strangely it did not splinter.

Enough to say that it was frightening. One of the cooks said "Bandy, can we have a smoke?" I reminded him that we were in Church, but he said that he did not think that Jesus Christ would mind. So we all lit up. Not long after that the cleats on the main bulkhead door were being undone, and the lad on the phone shouted "Padre's coming". You should have seen those fags go out but you could not take the smell away! He had come to pray so we all prayed, and when he was leaving he said "Bandy, you would be more use in the sick-bay" so we went back together.

As we got to the sick-bay, the ship's Commander and damage control party were there. Some were below fighting a fire and the Commander said he thought there might be wounded there. My First-Aid kit was still in the Chapel, and thick smoke was coming out of the hatch. I did not know what I would find down there but everyone seemed to watching me so down I went. It was the lower steering position.

What a mess! Men fighting the fire by secondary lighting, hardly able to see very much. One thing I did see was a young lad on the wheel conning the ship and listening to orders on the voice pipe, surrounded by men putting out the fire. He was brave. What I did not realise at the time was that the main control of the rudder had gone, and that all of us were in his hands. When you think that we were in a river which was getting narrower and all of us were relying on him. One young lad. It was hard to describe that scene.

In the dim light I saw someone on the deck. He touched my leg. I spoke to him and he told me his leg was gone. It was now getting unbearable down there so I went to the hatch, and they passed me a Neal-Robinson stretcher. I felt his leg but could not see: I got two handkerchiefs and tied them together and put them around his leg. I got a piece of wood twisted it round, and put the end of the wood under his belt. I got him up the hatch, took him to the PO's Mess and laid him on the table. I had a word with him and he was still conscious. I told him to wiggle his toes: he did, or thought he did and then passed out.

The mess was full of wounded so I had a quick word with those that wanted to talk and lit their cigarettes. The I went back to the sick-bay. Nothing much could be done here. It was full of wounded, with the Padre holding the hand of the rating from CONSORT, Doctor Taylor working on a massive blister, and the sick-bay still on the bad side of the ship.

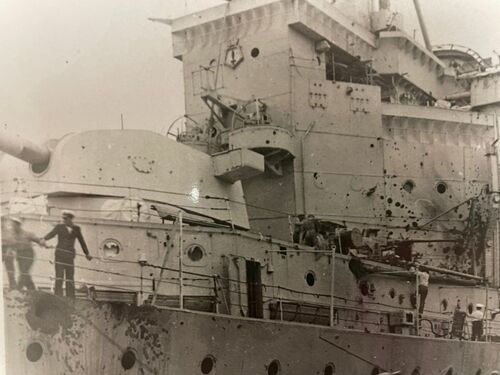

Our bridge had been hit, the Chinese Pilot killed, our own navigator seriously injured and the Captain wounded. The river was now getting narrower and a decision had to be made to withdraw for in no way could we go much further and turn this 12000 ton Cruiser.

We felt the ship's bow rise and then we hit the sand bank. Then full-astern, and we were on our way down the river. All our steering was now being done from the lower steering position; no errors could be allowed with no open-sea to rectify them, and our Captain was still on the bridge.

Our 4 inch guns should now have fresh crews, but so many had been wounded, it meant that those who were still fit just manned the other side. It was fortunate for us that no one fired at us when the ship was turning. The journey down was a lot easier, mainly I suppose because the flow of the river put about another seven knots on our speed and this gave HMS BLACK SWAN a better chance of keeping up with us. Anyway there was little ring.

The sick-bay now became a busy place. The Padre was still holding the hand of the man from CONSORT, and Doctor Taylor was over in the Petty Officer's Mess, deciding who was going to be brought into the sick-bay for treatment. It was the lad that I had brought from the lower steering position. His foot had gone, so Doctor started work. The first big snag was no water, as the pipes had been blown apart and all we had in the sick- bay was a tank with about ten gallons of distilled water in it. We poured into the basin a gallon of dettol for washing the instruments.

Our Sick Berth Petty Officer showed me how to give pentathol and what to look for while doc was operating, and he went to see to our navigator. All of us knew he could not live. His eyes were open and there was no blood; all that was missing was his hat. My thoughts went to the bridge. He still looked so clean, you would have thought that he was ready to go on watch. We ran out of Pentathol and Doctor Taylor said. "It's ether now Bandy" and believe me I got worried. Then what was music in our ears, the order "Fall out from Action- stations came over the speakers. We could now at least try in a small way make our injured more comfortable.

We had ratings lining up outside the sick-bay only to be told "go away, we will pipe when we want you"; shrapnel did not count as a wound on that day!. Our young Doctor (Australian) had only been on board for a week. His first ship. What a christening! He came in, took over from me. And together they got down to work.

One young lad in there called Warwick had his buttock shot away. This we packed with gauze, and then it was plastered but we knew he could not live as gangrene had set in.

The ship tied up at Holt's Wharf in Shanghai for temporary repairs, and work was to continue on the wounded for in no way could we land them in Shanghai.

Our Captain came down from the bridge and went around the ship thanking ratings as he met them. He came to the SB, thanked us all, and then he was taken to his quarters for treatment. The Admiral relieved him of his command, and promoted the Commander to Captain.

My time during the first night was spent making dressings and tea, talking to the wounded while they waited for treatment, and when morning came I think that all had been comfortable.

The Americans had placed their hospital ship at our disposal. It was called REPOSE, and at about 0830 a landing craft came alongside to collect our wounded. We loaded about twenty seven aboard on stretchers, and the tank landing craft had an awning stretched right over it.

It was a dirty drizzly day but not in any way cold. I spent my time just talking to the wounded. Young Warwick told me that he was going to die. We all knew this but I promised him my tot of neat rum when he came back aboard and gave me a lovely smile. How that landing craft vibrated! Then we were soon going alongside REPOSE. What a massive ship! Just like going alongside the QUEEN MARY. The baggage hatch opened and out came the cranes to lift our stretchers but they would not fit, so we just tied them on but we got all the men aboard alive and this was great. Then we cast off and proceeded back up river. Where we were going I did not know. I just hoped that it was back to HMS LONDON and I thank goodness it was. I went up the gangway and reported to the Officer of the Watch, "All wounded aboard REPOSE and alive".

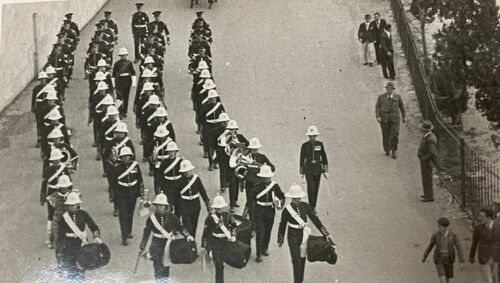

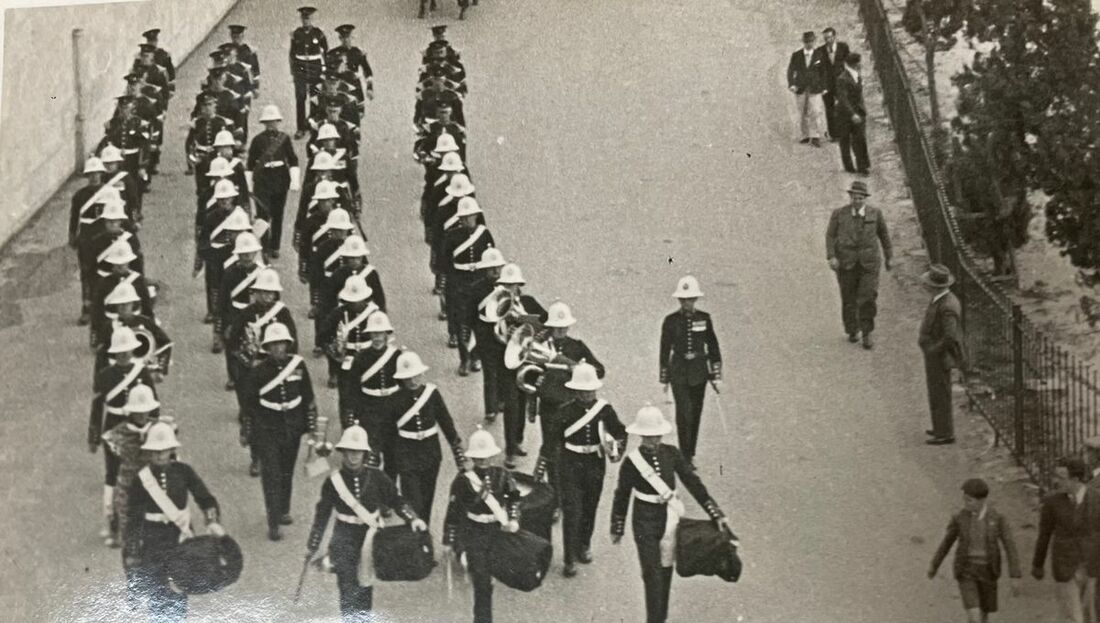

After the action, when we were turning towards Shanghai, one of my band Corporals came down to the sick-bay and asked what they should do. I told him to take the band on deck and play some rousing marches, and when the ship passed Garden bridge (this was the international part of Shanghai) to tell Tubby Langsale to play the "Post Horn Gallop" with band accompaniment, to let all the people know that although we were battered we were still winning. My Band went ashore for the funerals of the dead from HMS LONDON, HMS CONSORT and HMS BLACK SWAN. They were buried from the Cathedral in Shanghai. The Reds had already entered the city. Jack Bulley, another of my Corporals, told me afterwards that he was more afraid then than he was during the action.

Bullets were flying from one side of the cemetery to the other, yet no one hurried; it is of interest here to name another Band Corporal who was the Drum-Major, his name was Umpleby. The Cathedral has been pulled down and blocks of flats built on the ground right across the cemetery.

We left Shanghai and sailed down Woosung Flats and anchored in Alacrity Anchorage to await the arrival of HMS BELFAST. As soon as she arrived the Admiral transferred his flag over to her and we were under orders to sail. One major snag then came to put a spanner in the works; the capstan would not work, so after all our setbacks it was just one more - up anchor by hand. This meant rigging sixteen capstan bars on the capstan, ten men to a bar, and the Band on B deck started slow pace, and gradually quickened. We could draw the ship to anchor but could not get it out of the mud, so after 4 1/2 hours of trying we took a link out of the cable and left it there.

On board HMS LONDON we had 160 boys, just over a quarter of our ship's Company, yet those lads never showed any fear in battle and they were a credit to the Navy.

We proceeded to Hong Kong, went alongside, and had our bridge repaired. They fitted new range-finders and tripod masts and hanger doors were put down and patched; I don't think we ever had new ones.

The REPOSE was already in harbour, and as a thank you the Wardroom gave an 'At Home' to all their officers. It was a very moving occasion. I was introduced to the Senior Doctor of the ship, and it was one of the longest At Homes' that I ever played for; 6 hours we kept going.

In the end the Skipper said, "Thanks Bandy. Take the Band away".

We sailed for Singapore and took on board the Commissioner General for Far East Asia, Malcolm Macdonald, the son of Ramsey Macdonald, and flew his flag. This I believe was the first time it had ever been done. At each place we visited it was Beat the Retreat and At Homes so the Band did have their work cut out. It was on this trip that we steamed over the spot where the battleship HMS PRINCE OF WALES had been sunk.

Back to Singapore and onboard came Rear Admiral Calson. Then the trip North Malaya and more work; others could get ashore but not the Band, except to Beat the Retreat. But after doing Tenqqanu, the usual Beating the Retreat, the weather turned bad.

The locals had been invited aboard for drinks and a cinema show. They were all aboard when we arrived at the jetty to find it empty, absolutely deserted. The wind started blowing, the rain poured, and we were wet through in no time at all. Then some one said, "Lets Beat the Retreat" so we did, all over again, in that terrible weather with no one to watch. While we were slow marching to "By Land and Sea" the pinnace arrived a flat bottomed boat, but only the Band were allowed to go back aboard so we left the Royals there in the rain.

They had plenty to drink, even if it was only rain water.

How the bottom never fell out of the boat I'll never know. We eventually got on board and the first thing said was "Get the Band up and give us some music, Bandy. Change your clothes. Empty the water out of the instruments and start playing".

It was a great occasion for all these people and they were going to have a late do. After drinks it was going to be cinema and in any case they had to stay all night for it was too rough for anyone to go to sea. We had head-hunters on board (our friends, thank goodness) only small men, but very strong. It was very late when we finished playing; hot drinks and sandwiches were passed around to the visitors and a very discontented band went down to the Band mess with duck-suits ruined, all the starch gone out of them and not a thing to eat from seven bells (1130), not even a cup of tea. I went to the Commander and asked if arrangements could be made to get something, even a tea-urn of tea.

You should have seen the smiling faces when the Commander arrived with crates of beer and pea-hen sandwiches. He stayed with us for about an hour, mainly I think because there was nowhere for the officers to sleep. After cinema women and children went in the cabins to sleep. In the morning it was a glorious day and after breakfast we mustered on the deck and played them all ashore. Our time on the Far Eastern Station was now drawing to a close and we returned to Singapore, visiting Malcolm Macdonald in his official residence.

It then came our turn to say goodbye. All the Chinese mess boys assembled, one or two in nearly every mess; the one in the band mess was No 1 boy on board. He had the biggest pay per month. How he worked! He laid food out, scrubbed the mess, dished up, pressed No 6 suits for a small charge, cleaned instruments (brass) all for extra money. All of them were going back to Hong Kong.

They too had been up and down the river with us. All went with our recommends and letters with the Ship's stamps on. There is only a very small fleet on the China Station now, but hopefully they would find a job somewhere.

We sailed for home, a slow journey, but a happy one. In the Suez Canal from the Bitter Lakes the south bank was lined with troops, a lovely sight. When it came to going up channel, I do not think anyone turned in. It was lovely seeing all the lights around the coast, and we arrived at Sheerness in the morning to a great welcome; quite a few of the Band had their wives come up and we all stayed in the NAAFI Club.

The Band transferred to HMS KENYA. The RM and Ship's Company stayed on board LONDON. Two days later I had a draft to Deal and parted from all the lads who had worked so hard to make the commission such a huge success.

On board HMS LONDON we had one amusing story of two Band Corporals during the action in 'B' turret shell - handling room. As the shell came up in the hoist it looked as though the tip of it was red hot, and I was told that no one had ever passed a shell up to the guns with such speed. What happened was that an amber light was glowing and reflecting on the tip of the shell!

On 1st November 1949 I was awarded the DSM and went to Buckingham Place to receive it on the 17th. It was given to me by King George VI in the Ballroom. He spoke to everyone. To me he said, "Thank you for looking after my men". The Queen said, "Where do you hail from?" I said "Wilcove, Ma'am."; "That's where Sir John lives" was the answer. My reply was "It's not on the map yet".

She laughingly responded with, "It will be after today".

They told the two Princesses to stop following them around and go and sit down.

My DSM, I believe, was the only peace-time DSM in the history of the Royal Marines and the only one presented to any member of the Band Service at Buckingham Palace.'

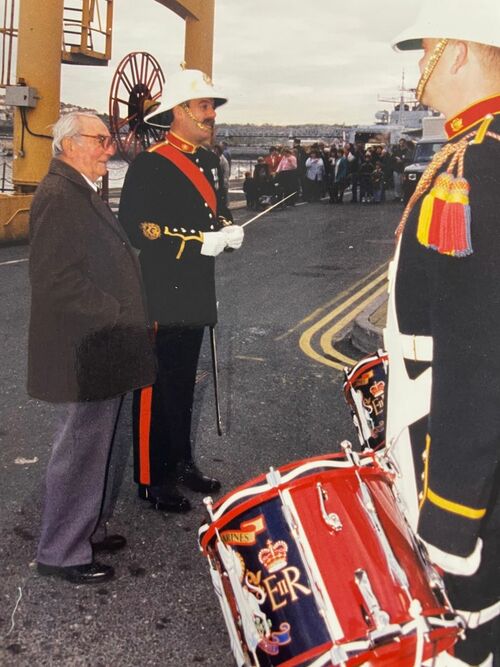

Further rewarded with a payment of £5-5-0 from the Naval Prize Fund on 20 October 1949, Harwood saw out his career and was Pensioned (No. 28062) on 19 October 1954. He was granted the honour of conducting the Royal Marines Band at Devonport Dockyard on his 80th birthday upon the arrival of Battle Axe.

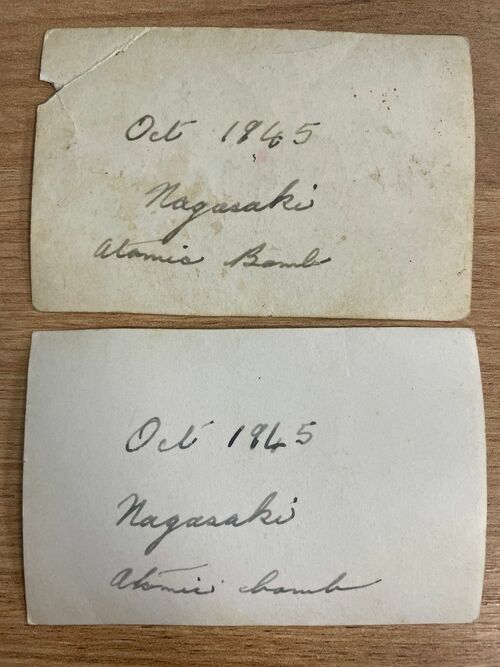

Sold together with an impressive original archive comprising:

(i)

His Certificate of Service, with its outer sleeve, besides Cadet Corps Discharge Certificate and his 1925 Standing Orders.

(ii)

Named box of issue for the Arctic Star, together with forwarding letter and Certificate, together with letter related to issue of the Malta Commemorative.

(iii)

A quantity of letters, telegrams and documents related to his career.

(iv)

His detailed accounts of his career and Yangtze incident, these never having been published in full.

(v)

Inter Room 1931-32 Royal Marines Medal, in its case of issue.

(vi)

His five photograph albums, including a plethora of unpublished images (including those of the devastation of the Atomic Bomb at Nagasaki, besides a fine selection of images of damage to London and burials), documents and other related material.

(vii)

Illustrated London News, No. 5771, Volume 213, 26 November 1949, worn overall.

Subject to 20% VAT on Buyer’s Premium. For more information please view Terms and Conditions for Buyers.

Estimate

£15,000 to £20,000

Starting price

£12000