Auction: 23003 - Orders, Decorations and Medals

Lot: 134

The Arab Headdress worn by T. E. Lawrence - 'Lawrence of Arabia'

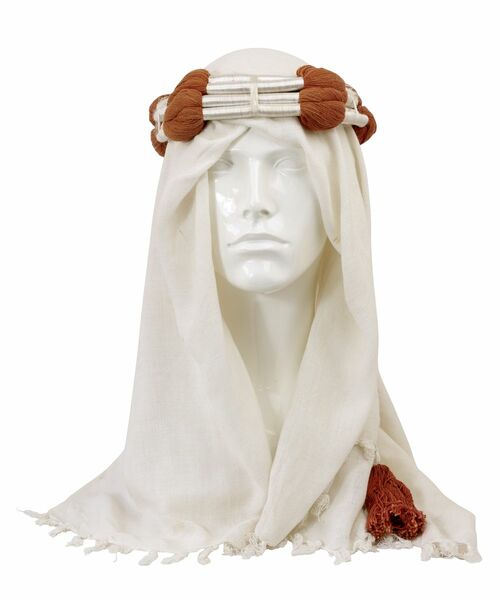

White cloth Keffiyeh, with tassels to the edges, with its Agal, this of the typical 'Lawrence' style, this being two pairs of bound white cotton thread bands, each conjoined and affixed with five larger sections of red/crimson thread, the ends with red/crimson chord and large tassel, overall in good condition as worn

Provenance:

By repute given by Lawrence to Flight Lieutenant Donald Stephenson circa 1933-35.

Given by Donald Stephenson (1909-93) to Lynda Pedleham - his house keeper - circa 1970.

Acquired by the present owner 2016.

'…a clever, agreeable and hard-working officer given to eccentricities.' - Lawrence James, The Golden Warrior: The Life and Legend of Lawrence of Arabia, (London, 1990), p. 130.

Had T. E. Lawrence's career continued as thus described in mid-1916, sourced by the historian Lawrence James from contemporary references, there would have been no legend of 'Lawrence of Arabia'. It was that legend that prevented him from slipping into a post-war obscurity about which, anyway, he consistently remained ambivalent. It is that legend which still lends a frisson to objects associated with him - such as this headdress.

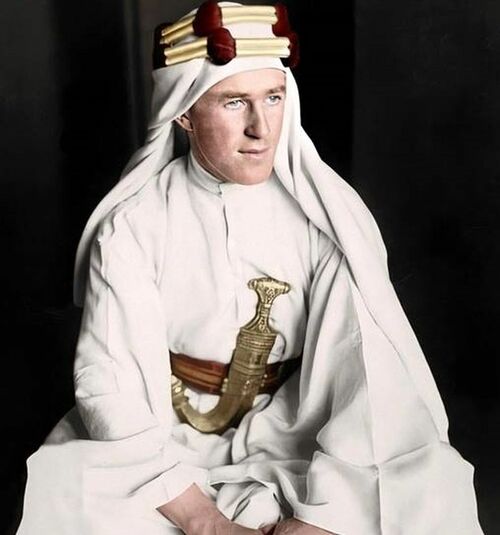

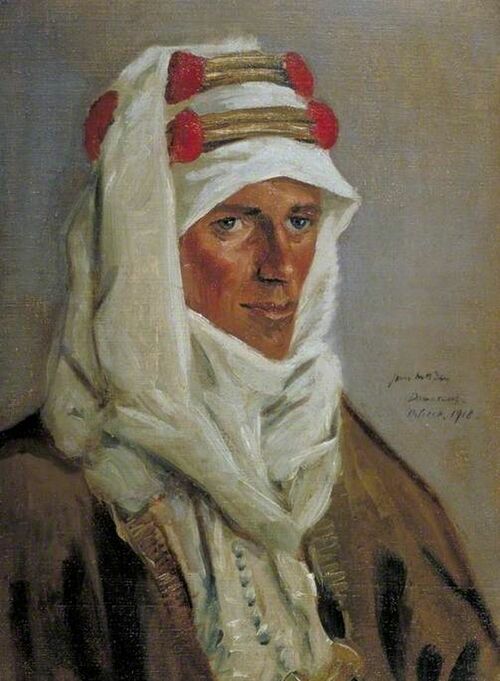

The Arab headdress, the keffiyeh head-cloth and agal circlet, is such a part of the Lawrence legend that it is tempting to apply to it that much-overused adjective 'iconic'. Different versions of the headdress appear in many portraits of Lawrence: it is evident that he owned and wore several styles of both components. A 1919 pencil sketch by Augustus John (National Portrait Gallery 3187) captured in a few lines Lawrence's ascetic profile and the Arab headdress: that Lawrence chose the sketch for inclusion in the subscribers' edition of Seven Pillars of Wisdom in 1926 contributed to both his legend and his iconography.

The Arab Revolt, which even Lawrence himself described as a 'sideshow to a sideshow', has been as well covered by historians as Lawrence's life has been analysed by his biographers. Erupting at a time when the scars of Gallipoli were fresh and the European battlefronts mired in bloody stalemate, the Revolt's effect upon the Middle East campaign rapidly attracted popular attention, first through newspaper coverage and then through the embryonic medium of newsreel. Although of limited strategic importance, the Arab (and especially the Bedouin) way of warfare gave Turkey's enemies the tactical advantage of guerrilla operations: tying down, distracting and harassing regular forces and disrupting communications, while being untroubled by the Hague Conventions and galvanised by the prospect of loot. That the British government felt the Revolt to be worthwhile is evidenced both by the enormous amount of gold paid to sustain it and by the gradual increase in regular forces and matériel supplied to supplement the Arab irregulars.

That Lawrence was intrinsic to the Revolt is beyond doubt. His relationship with the Emir Feisal was of critical importance to such cohesion as existed within the Arab guerrilla forces and Lawrence's evident ability to inspire trust in Feisal and other Arab leaders verged upon the unique. His facility with the Arabic language, obvious Arabist sympathies and willingness to adopt Arab customs - including the wearing of Arab dress - increasingly defined him and made him indispensable to the Revolt. He had first worn Arab headdress as early as 1912 when working as an archaeologist in Syria and so had no qualms about adopting it, and all other elements of Arab dress, at Feisal's invitation. Not only was such attire far more practical than British military uniform in the desert, it also unmistakeably identified him as both a confidant of Feisal and 'one of us' among the Bedouin - whose distrust of outsiders and particular dislike of Western headdress was recorded by Lawrence. At the same time, the nonconformity of the Arab headdress (as compared to the peaked caps, solar topis or 'Wolseley Helmets' worn by more conventional British soldiers) particularly appealed to the showman in Lawrence, which may be why he continued to wear Arab headdress even when otherwise dressed as a British officer and in such climatically unsympathetic locations as Paris and Glasgow. Lawrence recognised that the quality of his Arab dress was important to his status: the robes and headdress he adopted, at Feisal's request, were those of a sharif and in 1917, as one of his guidance notes for beginners in dealing with the Bedouin, he wrote, 'If you wear Arab things, wear the best.'

That Lawrence was as assiduous in acquisition as he was generous in donation is clear from the mass of material associated with him that survives in public and private collections. The Imperial War Museum, National Army Museum and RAF Museum all contain Lawrence-related items, as do All Souls College, the Ashmolean Museum and the Museum of the History of Science in Oxford, the Museum of Costume in Bath and, of course, Clouds Hill in Dorset. Most such items were given by Lawrence to friends and acquaintances and subsequently donated by them to the museums; others have remained in private hands. As Lawrence sought in the 1920s to shed the skin of celebrity for one of calculated anonymity in the ranks of the RAF and the Tank Corps, so the trappings of that celebrity were relinquished: a robe here, a headdress there, a dagger sold to finance the restoration of Clouds Hill. The headdress offered here is reputed to have been given by Lawrence to an RAF officer; it then passed to that officer's housekeeper before being acquired by its present owner. It may perhaps be of significance that a very similar agal (of purple silk and silver wire) was given by Lawrence to the wife of his RAF commanding officer at RAF Cattewater (later Mount Batten), Plymouth, between 1929 and 1931 (National Portrait Gallery exhibition 'T.E. Lawrence', 1988, catalogue number114) - that realised a Sale Price of £27,500 when sold at Chrisite's in September 2016. Recently colourised images of Lawrence wearing such headdress also reveal their colours being strikingly similar. Also worth noting is the fact Stephenson was an Arab language specialist, perhaps a shared love that meant their paths crossed.

Sold together with Stephenson's scarce 1935 pattern (MEC No. 1935) Royal Air Force Waist Belt with cross straps and two magazine pouches for the 1911 Colt pistol, this inscribed in ink on the inner portion 'D. Stephenson R.A.F.'

Subject to 20% VAT on Buyer’s Premium. For more information please view Terms and Conditions for Buyers.

Estimate

£14,000 to £18,000

Starting price

£12000