Auction: 23002 - Orders, Decorations and Medals

Lot: 145

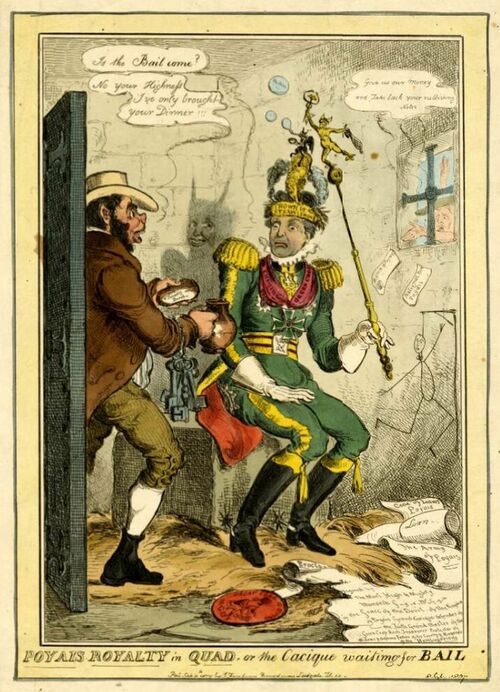

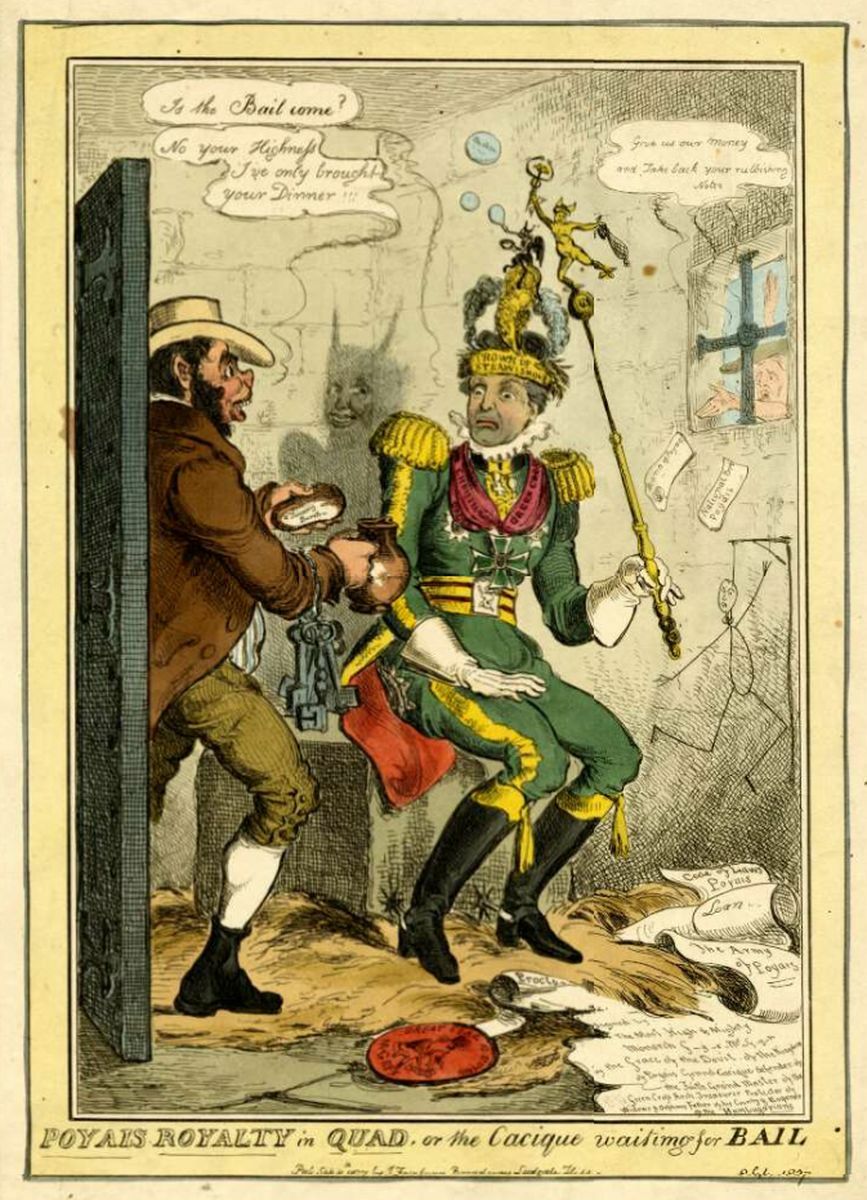

The fascinating and rare Order of the Green Cross of Poyais, a bogus Order of Chivalry for a country which never existed, invented by one of the greatest fraudsters in history, a Scottish-born adventurer, soldier, confidence-trickster and sometime Venezuelan General by the name of Gregor MacGregor

Order of the Green Cross, 70mm including ring suspension, gold and enamel, unmarked, a most striking Badge, good very fine and better

The 'Poyaisian Scheme' (or Fraud) was the idea of the Scottish soldier and arch con-artist Gregor MacGregor. He began his life of adventuring as a soldier-of-fortune in Venezuela and Colombia, and in 1820 he visited what is today Honduras. There - he claimed - he obtained a grant of eight million acres of land from George Frederick Augustus I, King of the Mosquito Shore and Nation. Returning to London, MacGregor began styling himself 'Gregor I, Cazique of the Independent State of Poyais' and set about publicising an ambitious scheme to colonise the land, legitimising this tale by setting up an office in London and selling bonds to investors. The lie began to unravel when, echoing the Darién Scheme of the late seventeenth century, a group of around two hundred settlers sailed to 'Poyais', only to discover that the land they had been promised did not exist.

After a promising start in life (marrying the well-connected and wealthy daughter of a Royal Navy admiral) and purchasing several commissions - rising to Captain - in the famous 57th (West Middlesex) Regiment of Foot, MacGregor began to show disturbing signs of a desire for undue status, prestige, and suffered from delusions of grandeur. After a falling-out with his Commanding Officer, he was seconded to the Portuguese Army and promoted Major; however he left the Peninsula shortly afterwards to return home and sold his commission. From 1810 he began styling himself 'Sir' Gregor and the holder of a Portuguese Order of Chivalry - both entirely false claims. Later that year his wife died, and with her his access to ready money and introductions into Society; hearing about the Struggle for Independence in Latin America, MacGregor was amongst the first 'soldiers of fortune' to travel out there to join the revolutionary movement in Venezuela. In this struggle he fought alongside the famous generals Francisco de Miranda and Simon Bolivar; he married the latter's cousin, Josefa, in 1812. Always looking for the next way of securing fame and glory he next hit upon the idea of capturing Spanish Florida and specifically Amelia Island, on the Atlantic coast of the state in what is now Nassau County: in order to fund this enterprise he issued scripts for $1000, which would entitle the buyer to 2000 acres of Floridian land once it had been secured. In this way, MacGregor was able to collect the astonishing sum of $160,000 for his invasion of Amelia Island - most of which appeared to go straight into his own pocket. After bloodlessly conquering the island, MacGregor dived headfirst into administration, producing a flag, medals, stamps and 'Amelian' currency - with which he paid his soldiers, to their chagrin - issuing official writs and licenses for trading; his hit-upon official symbol was the Green Cross.

A mutiny among his men and the looming threat of a Spanish attack eventually forced Gregor to flee to the Bahamas, and from there he headed back to London where he endeavoured to raise further troops for the liberation of Venezuela from among the recently unemployed and discharged servicemen of the disbanding British Army at the conclusion of the Napoleonic Wars. Returning once more to Latin America, MacGregor launched an independent, immediate and underwhelming attack on the first Spanish outpost the expedition encountered, at Portobello. There they suffered a tragic defeat during which MacGregor jumped out of his bedroom window into the sea to escape enemy troops, an act which he would later transform into a story of courage and daring. After this embarrassment, Bolivar disassociated himself from MacGregor, who proceeded to sail alone to the Mosquito Shore where further tall tales were spun. Arriving back on British soil in 1820, MacGregor made a grand announcement: he had apparently been created the 'Cazique' (King) of the Principality of Poyais, an independent nation on the Bay of Honduras, by King George Frederic Augustus I of the Mosquito Shore and Nation. Not only did the 12,500-mile territory of Poyais (over which he now ruled) boast fertile land, untapped resources, a small number of British settlers, and co-operative natives, but MacGregor had already implemented the beginnings of a civil service, army and democratic government. Now he needed further settlers and investment, and had come back to Britain to give its people this once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.

In 1822, a ‘Sketch of the Mosquito Shore’ was published to promote the project, a book supposedly authored by one Thomas Strangeways, Captain in the 1st Native Poyer Regiment and MacGregor’s Aide-De-Camp - but it may well have been the work of MacGregor himself. The ‘Sketch’ provided a great deal of information on the colony: the capital of St. Joseph had been founded by English settlers in the 1730's; huge deposits of gold and silver lay hidden beneath its fertile soil; local labour promised to be cheap; and the prospect was beautiful, being "full of large rivers, that run some hundred miles up into a fine, healthy and fruitful country". It was also conveniently sheltered from Spanish incursion by an impassable mountain range. Moreover, the country already had the beginnings of a colony: a democratic government, a bank and an opera house already awaited further settlers. All of this was, of course, total fiction. MacGregor also presented a range of other documentation to interested parties, including a manifesto that he had drawn up for the native 'Poyers', promising that the only immigrants permitted would be "the industrious and honest, none others shall be admitted among us", and the official certificate issued by George Frederic Augustus I to place him in charge of this seemingly perfect country.

The inspiring project, the exotic nature of Poyais, the multitude of documentation available to the public, and the general mania that surrounded Latin America at the time, generated thousands of investments and was immensely successful, with the result that MacGregor actually ran out of land to grant, being forced to issue bonds instead. These ensured backers a healthy share of the profits that were guaranteed to come from a Poyais invigorated by European investment and immigrants. So popular was the scheme that the share price of 2s/3d per acre (as originally advertised) was soon advanced to 2s/6d, and then later increased again, eventually reaching no less than 4 shillings. From farmers attracted by the promise of cheap and fruitful land, labourers desperate for a new start in the economic slump in the post-Napoleonic world, to wealthy families who bought commissions in the new Poyaisian Army for their sons, thousands were won over by the machinations of MacGregor. The 'Cazique' arranged the first voyage of 70 emigrants from London aboard the Honduras Packet, whose crew had apparently been present at his creation as the new ruler of Poyais two years earlier. He personally saw off the voyage, which set sail on 10 September 1822 under the flag of the Green Cross. A few months later a second ship, the Kennersley Castle, set off from Scotland with almost 200 further settlers. After personally greeting and exchanging pleasantries with many of the passengers, MacGregor was rowed back to shore amid cheers and applause, while the ship set off on its journey across the Atlantic.

When the new arrivals set foot on the sandy shores of Poyais, they were met not with an official welcome party organised by the local government, but by the desperate settlers who had arrived a few months earlier on the Honduras Packet, and who were still living in tents on the beach. It transpired that the broad avenues, porticoed European-style buildings and friendly locals promised by their ruler simply did not exist. Coupled with the arrival of torrential rains that brought with them insects, disease and landslides, the disappointment was too much for the new inhabitants of Poyais, who sunk into despair, mutiny, violence and suicide. At last, in May 1823, a ship carrying an embassy to the Mosquito King from British Honduras discovered their rudimentary camp. To their horror, the settlers were informed that Poyais did not actually exist and were advised that their only hope of survival lay in travelling onwards with the ship to Belize. With the exception of thirty people too weakened by illness, all the settlers decided to take their chances in Belize rather than remain in their imaginary country. Of the 250 immigrants who set off to Poyais, only 50 lived to see Britain again. Remarkably, upon their return, they denied that they had been duped by MacGregor, blaming instead his associates and agents who had so passionately pitched the wonders of Poyais to them - undoubtedly MacGregor did nothing to change their minds. Even before the return of the victims of his fantasies, MacGregor was suffering financially as a result of reduced investment in the scheme. In 1823, shortly before their return, he had fled to Paris where, astonishingly, he set up another similar fraud selling shares in Poyais, presenting himself with the Gallicised title of ‘Cacique’. He was even imprisoned in Paris for several months but eventually acquitted of all charges thanks to the skill of his lawyers and not attending his own trial in person.

By the time he returned to London in 1826, the initial scandal that had erupted around the Poyaisian fraud had died down. Despite the ignominious failure of the venture, MacGregor was able to maintain his reputation because public disapproval was focused on the speculators in South American loans rather than on his misrepresentation of Poyais - indeed, a pamphlet warning investors about Poyais published in 1827 makes no mention of MacGregor at all.

Following the death of his wife and increasing demands for repayment of the promised Poyaisian interest, he moved to Venezuela in 1838, where he was reinstated as a General and awarded a pension for life. There General Gregor MacGregor lived out his final years before dying in 1845 at the age of 58. He was buried with full military honours and subsequently celebrated as one of the country’s liberators from the Spanish.

Sold together with a silver medallion, 55mm, the obverse bearing a depiction of Victory bestowing a crown of laurels to Freedom, the reverse bearing the text: 'A Simon Bolivar, Libertador De Colombia, Y Del Peru, El Congreso De Colombia, Ano De MDCCCXXV'.

Subject to 20% VAT on Buyer’s Premium. For more information please view Terms and Conditions for Buyers.

Sold for

£2,700

Starting price

£320