Auction: 23002 - Orders, Decorations and Medals

Lot: 79

'When the flood in the engine room was 16 feet deep Captain Dawson ordered his volunteers to stop and save their lives.

They launched a raft and were waiting for their captain when the rope parted and a wave carried the raft clear. Another wave made the ship heel over, and Captain Dawson, racing down her side, dived as she took her final plunge.

"It was touch and go on my getting away," Captain Dawson said yesterday. "I managed to pick up a lifeboat light and clung to it. Then I found a float and got on it. I was picked up two hours later … '

The miraculous survival of Captain W. T. "Bill" Dawson, following the loss of his command, the S.S. Sourabaya.

A notable and well-documented Second World War Atlantic convoy O.B.E. group of six Captain W. T. "Bill" Dawson, Merchant Navy

Having somehow survived four days in an open boat, after the tanker Peder Bogen was torpedoed and sunk by the Italian submarine Morosini in the South Atlantic in March 1942, he took command of the S.S. Sourabaya

But she too fell victim to a torpedo attack - delivered by the U-436 in the Atlantic - just six months later, his leadership and gallantry on that occasion leading to the award of his O.B.E.

A long-served and much respected mariner, Dawson was Master of Trinity House, Leith, from 1964 to 1977

The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire (O.B.E.), Civil Division, Officer's 2nd type breast badge; 1939-45 Star; Atlantic Star; Italy Star; Pacific Star; War Medal 1939-45, mounted as worn, good very fine (6)

O.B.E. London Gazette 23 May 1943. The joint recommendation states:

'The ship was torpedoed. The fires were at once shut off, the engines were stopped, and the machinery spaces vacated. After inspecting the damage, the Master [Dawson] decided that there was a chance of saving the ship. He ordered the passengers and the majority of the crew into the boats and called for volunteers to operate the necessary pumps.

Officers Tyson, MacKenzie and MacDonald with Firemen Murdock and Sandilands volunteered for this dangerous task. Returning below, they re-lit the furnaces and proceeded to pump out two of the cargo holds. They also worked the engines as required by the Master in his attempt to place the ship in a favourable weather position. Conditions made this impossible and it was decided to try and pump out another tank, but the leakage into the engine-room was more than could be dealt with and eventually the fires were put out by the rising water. It was only then, with 16 feet of water in the engine-room, that those below relinquished their efforts and the ship had to be finally abandoned.

The Master showed splendid courage, resource and leadership throughout. After getting away as many as possible of those on board, he made determined efforts to save his ship in circumstances of great difficulty and danger.'

William Thomson Dawson was born on 24 January 1910 and was educated at Trinity Academy, Leith prior to joining the Merchant Navy as a Cadet in 1925, when he joined the steamer S.S. Albuera. She was a vessel of the Leith whaling company Christian Salvesen & Co., and Dawson undertook at least one voyage in her to the Falkland Islands. Subsequently qualifying as 3rd Mate in 1929 and 2nd Mate in the following year, Dawson was serving as 1st Mate of the Seringa by the outbreak of hostilities in September 1939. His next appointment was aboard the Southern Princess, commencing in May 1941.

Loss of the tanker Peder Bogen

Sometime thereafter, he took command of the tanker Peder Bogen but it proved to be a short-lived appointment: she was torpedoed by the Italian submarine Morosini south-east of Bermuda on 23 March 1942 and finished off by gunfire. Eric Wiburg's nautical website takes up the story:

'A veteran of numerous convoys since the outbreak of the war, the valuable tanker Peder Bogen is described as having a gross tonnage of 9,741 tons and was loaded at the time of attack with 11,020 tons of Admiralty fuel and 2,000 tons of bunker oil (for her own use). She was steaming from Port of Spain, Trinidad, which she had left on the 19th of March, carrying the radio officer of the British tanker Melpomene, to Halifax, then destined to sail for the U.K. Her departure from Trinidad was remarkable in that she had an escort of a patrol boat and airplanes and for the first six hours or fifty miles sailed north with three other ships in two columns. This is evidence not only of the importance of the laden tanker to the war effort, but also the onslaught of German and Italian submarines off Trinidad even at this early stage of America's entry into the war (Kelshall).

Peder Bogen's speed at 1615 (4:15 PM local time) on the 23rd of March was 9.5 knots and her position 24.43 North by 57.44 West, roughly 700 miles northeast of Puerto Rico - this is just outside of the strict area covered, however the fact that she was struck by the Italian submarine Morosini, whose position is difficult to pin down, coupled with her carriage of a survivor of the Melpomene sunk 5 March by the Finzi, merits this ship's inclusion. Also, because the survivors were landed in both the U.S. and Europe (New York and Lisbon), the demise of the Peder Bogen is covered thoroughly by both U.S. and U.K. Naval Intelligence. Captain Dawson was interviewed by the British a mere 9 days after arrival in Lisbon.

At the time of sinking conditions were calm, it was daylight, and visibility good - the wind was described as South-east, force two (about 20 miles per hour). The Peder Bogen was sailing independently on a straight course, not zigzagging, course roughly due north and just skirting the line between Bermuda and Anegada. One seaman was on watch on the bridge and her 4-inch gun was manned by a Naval Gunner on the after gun. Altogether the ship was armed with the 4-inch gun, twin Marlin machine guns, 2 Hotchkiss guns, 2 strip Lewis guns and 4 rockets and kites. There were 51 men under the command of Captain W. T. Dawson, plus the one passenger, for a total of 53. These included five gunners - two army and three naval.

Two torpedoes from the Morosini struck the ship on the port side - the first forward of the bridge in the number six tanks and the second just forward of the engine room in the number one tank, giving off the smell of cordite. As Captain Dawson wrote, "the fore end of the midship house [was] blown right away and the bridge partly wrecked. The bridge protection was cement and stood the concussion very well. The big hatchway across the fore part of the bridge was blown open. A hole was blown in the ship's side 5 or 6 feet above the water line, and I could look down from the bridge and see the interior of the ship" (ADM 199/2150 p.83). Fortunately no one was injured, and ten minutes hour later Captain Dawson boarded one of the two lifeboats (out of six) which had launched from the starboard side and abandoned ship. There were 21 men in the Master's boat including five engineers, two mates, two soldiers, and two naval gunners. The lifeboats stood off roughly a mile away, riding on their sea anchors. At 7.30 p.m., after three hours of waiting (1800 and two hours, according to Captain Dawson), the ship had still not gone down, so the survivors decided to re-board the Peder Bogen. However, as they approached the ship the submarine, which had obviously been waiting for this cue, sprung into action and began shelling her from the distance of one mile away. The Morosini gun crew employed both tracer and explosive shells and chose to fire from dead ahead, which gives a much smaller target than broadside. Not surprisingly, according to the lifeboat crew, their accuracy was not very good, with some forty shells fired and only five or so hits.

As Captain Dawson, with characteristic British understatement and aplomb related, the shells were "passing overhead, for over an hour and our situation was becoming more dangerous. We saw the flashing of a morse signal slight some distance astern of the boat and formed the idea that there were two submarines in the vicinity and I considered it advisable to get away from the area as quickly as possible." A fire was set by the shelling which soon engulfed the ship, dooming her. Dawson says that "when I last saw the ship from the boat she was down by the head and burning furiously to the water line" (Id.).

The lifeboats beat a hasty retreat and lay off a mile away for the duration of the miserable night, watching their now "uninhabitable" home burning furiously. In the morning they set off to the south-west and the Caribbean islands in the direction of the Virgin Islands. There were 32 men in the Chief Officer's boat and they were soon separated. Captain Dawson set a course for Puerto Rico but because of light and fluky winds (they were from a different direction every day), they had to row the first four days. Fortunately it rained every night, enabling the crew to remain nourished and meaning that the rations for the 21-day trip which was envisioned would last longer. Each man had a waterproof suit and the boat was provided with 8 blankets, so aside from getting sores on their feet (the boat leaked heavily the first day until cracks were sealed with cement and by the natural swelling of the wooden planks), the men were alright on their ration of a quarter-pint of water daily. Dawson states that their fear of the enemy was so great that "I was afraid of risking keeping a light in the compass during the night-time. This was an entirely new experience for me, having had no previous experience of sailing a boat, except for pleasure" (Id.) Twenty-one in Captain Dawson's boat were rescued on the 4th day adrift (27 March) by the neutral ship Gobeo, which took them to Lisbon, Portugal, arriving on 12 April. Dawson relates how at 0600 (dawn) "one of the look-out men in the bow sighted a ship. We hoisted the yellow flag but I learned later that she had seen the sail of the boat before the yellow flag. …We were treated very well indeed, most of the Spanish crew appeared pro-British. They did not have very much variety of food, but they gave us what they had." In contrast to the little lifeboat which was afraid to light a bowl-sized compass, the neutral Gobeo "burned full navigation lights during the night." Commenting on his guest from the Melpomene, he observed that "the passenger, two ordinary seamen and myself were the only ones not to suffer from seasickness, most of the others suffered very badly and had to receive attention constantly" (Id.)

The balance of 32 men in the second boat were rescued at midnight on the same day, the 27-28 March. They were landed in New York by the Argentinian ship Rio Gallegos on March 31. All of the crew were British. Captain Dawson, having ensured the safe arrival of over 50 men across thousands of miles of oceans after a traumatic sinking closes his account modestly, observing that "The Mate and I were determined to get the boat and its occupants to safety - fortunately the weather and water were fairly warm throughout." (ADM 199/2140).

Given that the rescue ships did not radio in the collection of survivors given the wartime conditions, it took two tense weeks for the survivors to learn the fates of the others. The only sight of the Morosini which the survivors caught was a "vague silhouette" so unlike the Cygnet and Athelqueen survivors, they were not able to give an accurate description of the Italian submarine.'

Loss of the S.S. Sourabaya

Having been repatriated from Portugal and given recuperative leave, Dawson next took command of the S.S. Sourabaya, an ex-whale factory ship converted for use as a tanker and supply ship. Fortuitously for posterity's sake, a fellow crew member, the Scottish artist George Plante (1914-1995), who had qualified as a Radio Officer in the Merchant Navy, captured some evocative scenes of both ship and crew, prior to her loss in October 1942. At about 2300 hours on 27 October 1942, when bound from New York for Liverpool in Convoy HX-212 - and carrying a cargo of 7,800 tons of fuel oil and 200 tons of war stores, in addition to landing craft as deck cargo - the Sourabaya was torpedoed by the U-436 - Kapitanleutnant Seibicke - S.E. of Cape Farewell. Following a gallant attempt to save the ship - Dawson, 36 crew, 24 passengers, 16 D.B.S. [Distressed British Seamen, themselves already survivors of the loss of a ship] and four gunners were picked up by H.M.C.S. Alberni and H.M.C.S. Ville de Quebec and landed at Liverpool on 2 November; tragically, 26 crew, 31 passengers, 16 D.B.S. and four gunners were picked up by the Bic Island, only to be lost when that ship was torpedoed and sunk by the U-224 on 29 October.

Postscript

Dawson, who went on to serve off Italy and in the Far East, was still actively employed at the age of 65, serving as a pilot to vessels on the Forth. A much-respected mariner, he was Deputy Master of Trinity House, Leith from 1959-60, Assistant Master from 1960-64, and as Master from 1964-77, and he died in December 1994.

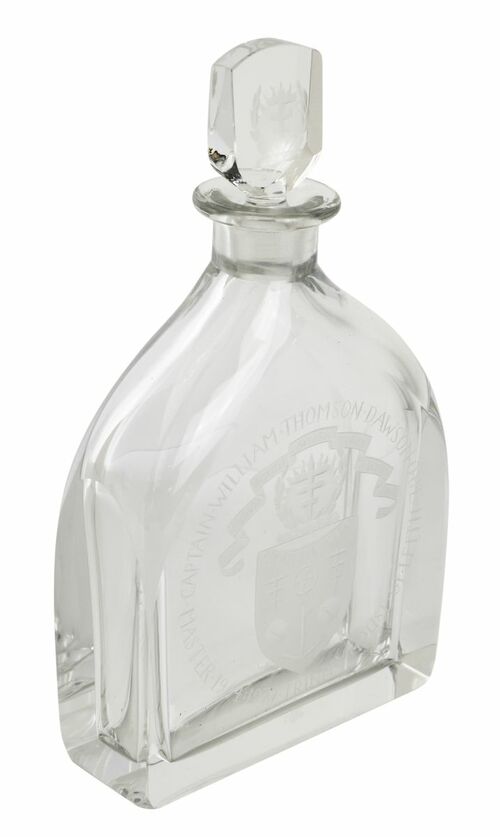

Sold with a good quantity of original documentation and career photographs (approx. 40 images), including the recipient's Board of Trade Continuous Certificate of Service, with ship appointment entries for the period May 1925 to September 1941, his Navigators and Engineer Officers' Union Membership Book, with wartime subscription entries, and his Certificate of Competency as Master of a Foreign-Going Steamship, dated 14 October 1948, together with a quantity of wartime newspaper cuttings, mainly concerning the loss of the Sourabaya and Peder Bogen, and one of his Merchant Navy peaked caps. Also sold with a magnificent presentation glass decanter, with engraved crest and inscription to, 'William Thomson Dawson, O.B.E. Master 1964:1977 Trinity House of Leith'.

Subject to 20% VAT on Buyer’s Premium. For more information please view Terms and Conditions for Buyers.

Sold for

£420

Starting price

£320