Auction: 23002 - Orders, Decorations and Medals

Lot: 62

(x) 'We all went down after them in one glorious rush and I saw Michael [Appleby] about a hundred yards ahead, open fire on the last Messerschmitt in the enemy line. A few seconds later this machine more or less fell to pieces mid-air - some very nice shooting on Michael's part. I distinctly remember him saying on the R.T., "That's got you, you bastard."'

David Crook praises the marksmanship of fellow 609 Squadron pilot Michael Appleby, leader of Blue Section in B Flight in a combat with Me. 109s in late September 1940.

The outstanding Second Word War fighter Pilot's group of five awarded to Flight Lieutenant M. J. Appleby, Royal Air Force

A pre-war member of No. 609 (West Riding) Squadron, Auxiliary Air Force, he fought throughout the Battle of Britain in the unit's Spitfires, gaining three confirmed 'kills' in addition to sharing in further claims and damaging several other enemy aircraft

In a combat over the Isle of Wight in August 1940 - the scene of fellow 609 pilot John Dundas's heroic encounter with the Luftwaffe ace Helmut Wick - Appleby's Spitfire was damaged by a Me. 110 but he managed to get his 'peppered' kite back to Middle Wallop

Such was his part in the momentous events of the summer of 1940 - including acting as an escort to Winston Churchill's famous but futile visit to France on 11 June - that he was among those selected to sit for a portrait by Cuthbert Orde

His story - and that of 609 Squadron - is described in compelling detail in the Squadron's history, Under the White Rose, and indeed in countless published works describing the epic combats and losses of 'The Few', among them fellow squadron pilot David Crook's Spitfire Pilot

1939-45 Star, clasp, Battle of Britain; Air Crew Europe Star; Defence and War Medals 1939-45; Air Efficiency Award, G.VI.R., 1st issue (Flt. Lt. M. J. Appleby, A.A.F.), good very fine (5)

Michael John Appleby was born in Edmonton, Middlesex on 16 February 1913 and was educated at The Leys School, Cambridge.

Interested in aviation from an early age, he joined No. 609 (West Riding) Squadron, Auxiliary Air Force, in December 1938 and was called up in the following year. Commissioned as an Acting Pilot Officer and placed on the strength of the Royal Air Force, he attended training courses at Little Rissington and Warmwell, prior to re-joining No. 609 in early May 1940.

Fast cars and first foray

An amusing glimpse of Appleby's time at Little Rissington is to be found in the Squadron's history, Under the White Rose, by F. H. Zeigler. As the first 'Auxiliaries' to attend a war course, he and his comrades came under regular R.A.F. discipline. One rule forbade the use of private cars, a rule swiftly abandoned when Peter Dunning-White and John McGrath of 601 "Millionaires" Squadron turned up in a Rolls Royce - complete with valet - and an Alvis Speed-Twenty. 'Even Michael Appleby of 609,' notes Zeigler, turned up 'in a drop-head Hillman'.

Meanwhile, with the advent of the Blitzkrieg, 609's pilots were keen to get to grips with the enemy, although the squadron was only ordered to action as Operation "Dynamo" reached its closing stages. Fresh from his war courses, with an 'above average' pilot rating, Appleby was destined to take part in 609's first - and only - foray to Dunkirk, on 2 June. The beleaguered French town was 'an awful mess', he recorded in his Flying Log Book.

Churchill's escort

A few days later, on the 11th, he flew a very different mission, 609 having been chosen to escort Winston Churchill and his War Cabinet on a secret trip to France to meet the likes of premier Paul Reynaud, Marshal Petain and General Weygand.

They rendezvoused with Winston's Flamingo aircraft at Warmwell, the commencement of a challenging cross-Channel flight owing to the limited speed of the Flamingo. In fact, the Spitfires had to break away to clear engines, prior to landing on 'a lake of long grass' at small airfield near Briare.

As the great and the good departed to their meeting, all Appleby and his fellow pilots could find was 'a wooden hut festooned with nude pin-ups and lots of champagne bottles, all empty.' Luck was at hand, however, for a wayside Bistro was located, at which much wine was consumed before they turned in for the night aboard a train.

The following morning, their return trip nearly ended in disaster, owing to a shortage of fuel and starter batteries. But for the timely assistance of an R.A.F. unit based in France, Churchill and the War Cabinet would have been compelled to take-off without their escort. As it transpired, honour was satisfied, so much so that 609 were once again selected to escort the Prime Minister to another urgent meeting at Tours a few days later.

It seems, however, that Churchill's aircraft recognition was not much good. In his famous history of the Second World War, he referred to his escort as 'Hurricanes' rather than Spitfires, and error finally put right in future editions by Appleby, who contacted the publishers.

First Blood

On 9 July 1940 - the very eve of the Battle of Britain - Appleby and 609 fought their first major combat, a clash with Me. 110s and Ju. 87s out to sea, off Weymouth. He claimed one of the Ju. 87s as destroyed but was then jumped by three Me. 110s on his tail, only just managing to fight his way clear at the cost of two spins.

It proved to be an eye-opening start for all concerned, David Crook describing how he joined up with Appleby before they 'bolted for the English coast like a couple of startled rabbits.' Crook 'made a perfectly bloody landing' and found his 'hand was quite shaky', and even his voice 'unsteady' as he afterwards spoke to Appleby about the combat. The latter noted in his Flying Log Book, 'Section leader failed to return'.

A nocturnal experience of the hair-raising kind

Over the coming weeks, operating out of Middle Wallop and Warmwell, 609 did indeed suffer mounting casualties, but with hard-won battle experience the squadron's gallant pilots began to turn a corner, although the employment of their Spitfires on night trials was a step too far.

On one such outing, Appleby, flying alongside John Dundas and David Crook, nearly met his end. Under the White Rose takes up the story in using his own words:

'John landed first, hitting a Bofors gun and damaging that and his Spit; David landed second and wrote off all the paraffin flares, and I was left stooging about in the dark, my petrol getting lower and lower, till they were re-lit.'

Then the flare-path indicator misled him by showing the wrong colours:

'Suddenly I noticed my altimeter was reading 100 feet - and that had been the height at which I had made my long approach over the fields, woods and houses, with a hill just 200 feet to my left! I throttled back completely, whereupon great flames licked out from the exhaust stubs, making it impossible to see anything below me, and I landed more by feel than judgement.'

Victories off the Isle of Wight and on the 'Glorious Thirteenth'

On 8 August 1940, 609 were vectored to a convoy under attack off the Isle of Wight, Appleby flying as No. 2 to his Squadron Leader. He closed a Me. 110 to 20 yards range and 'gave him all there was and both engine cowlings and the upper part of the cockpit cover came off and he dived into the sea'.

Appleby's Flying Log Book entry further noted the accuracy of the enemy rear gunner's return fire, namely three hits, 'one through the prop near the root, another in the wing just below the cockpit, and one in the wing tip'. Nonetheless, pilot and 'peppered' Spitfire returned to base.

Five days later, on what became known as 'the Glorious Thirteenth', 609 Squadron fought one of its most successful engagements of the battle so far, one pilot describing it as 'a memorable tea-time party over Lyme Bay'. No less than 13 enemy aircraft were shot down in just four minutes, Appleby claiming a Me. 109 and a Ju. 87 as damaged.

Winston Churchill and a significant gathering of "Top Brass" - out inspecting coastal defences - broke off their survey to marvel at 609's remarkable tally, at one stage five enemy aircraft being seen to go down in flames.

Such scenes undoubtedly inspired the Prime Minister into making his famous 'The Few' address to the House of Commons just a week later: 'Never in the field of human conflict was so much owed by so many to so few.' To which a rebellious Appleby was heard to add in the Mess, thinking of his pay as a Pilot Officer, ' … and for so little'.

Battle of Britain Day and beyond

On 15 September 1940, Appleby flew three operational sorties, on the third of which, with John Dundas and another pilot, he shared in the near destruction of a Do. 217 over the Channel. The enemy aircraft turned back for the English coast and made a crash-landing.

Other sources credit him with damaging further enemy aircraft on the same date, and this may well have been in 609's earlier clash over central London, in which, memorably, a downed Dornier crashed into the forecourt of Victoria station and, its tail-unit, 'just outside a Pimlico public house, to the great comfort and joy of the patrons', or so 609's War Diary states. Two of the Dornier's crew managed to take to their parachutes and landed on the Oval. Fortunately, without disturbing any cricket.

Finally, as leader of Blue Section of B Flight, Appleby destroyed a Me. 109 on the last day of September, when six of them 'inadvertently flew across their bows'. David Crook takes up the story:

'We all went down after them in one glorious rush and I saw Michael [Appleby] about a hundred yards ahead, open fire on the last Messerschmitt in the enemy line. A few seconds later this machine more or less fell to pieces mid-air - some very nice shooting on Michael's part. I distinctly remember him saying on the R.T., "That's got you, you bastard."'

As stated above, Appleby was among those selected to sit for a portrait by Cuthbert Orde, a sitting duly enacted in the Officer's Mess at Middle Wallop in November 1940 - 'it took about an hour'.

Subsequent career

At the end of the same month, Appleby attended an Instructor's Course at the Central Flying School at Upavon.

He subsequently served in that capacity at 11, 17 and 21 Elementary Flying Training Schools from January 1941 up until his release from the R.A.F. in the rank of Flight Lieutenant in September 1945.

As supported by an accompanying 'Recommendation for Honours and Awards' form, signed and dated 8 June 1945, Appleby was put forward for the award of the Air Force Cross (A.F.C.):

'Flight Lieutenant Appleby joined this unit [21 E.F.T.S.] on 21 April 1942, after a tour of duty with Fighter Command.

He is a Flying Instructor of great ability and exceptional judgment and his work has been of great value to the Station.

As a Flight Commander, his powers of leadership and his exceptional organising ability have been apparent throughout the time he has served here and have been instrumental in maintaining the outstanding efficiency of his Flight. He has recently been appointed Assistant Chief Flying Instructor.

He is strongly recommended for the award of the Air Force Cross.'

The recommendation was unsuccessful.

Having relinquished his commission in February 1958, Appleby died at Beverley, Yorkshire in January 2002. Sold with an archive of original documentation and photographs, comprising:

(i)

The recipient's R.A.F. Pilot's Flying Log Book, covering the period December 1938 to July 1942.

(ii)

The above cited recommendation form for the award of the A.F.C., signed by the C.O. of No. 21 E.F.T.S. at R.A.F. Booker, and dated 8 June 1945.

(iii)

A hand-painted 609 Squadron crest, mounted on card; central white rose with crossed hunting horns and motto 'Tally Ho'.

(iv)

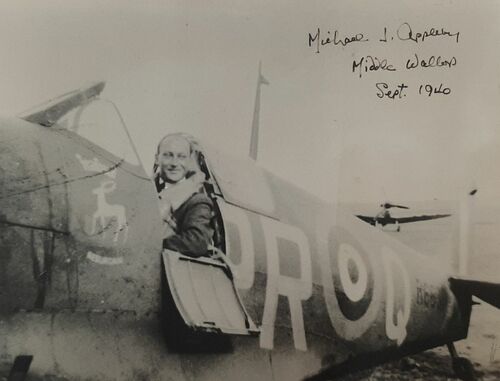

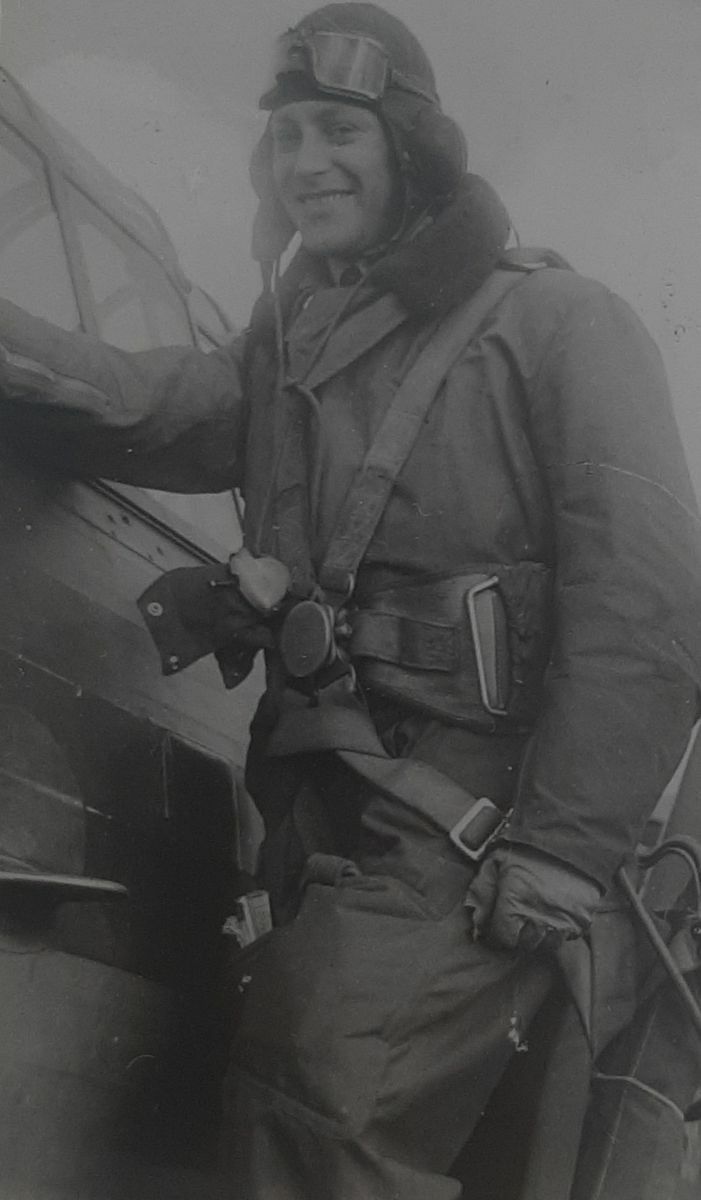

A selection of wartime photographs, including Appleby and his Harvard at Little Rissington in early 1940; an air-to-air photograph of him in his Spitfire on patrol over the south coast, and another of him seated in his Spitfire's cockpit at Middle Wallop in September 1940; group images of 609 pilots at Middle Wallop and Warmwell at the height of the Battle, including Appleby, all personnel identified; and two scenes from Middle Wallop taken at the time of an enemy raid on the airfield, including Appleby in a slit trench, wearing a tin helmet.

(v)

Named invitations to the Guildhall for the 25th and 40th Anniversaries of the Battle of Britain, together with later letters from the recipient with explanatory notes in respect of his career and the accompanying photographs.

Subject to 5% tax on Hammer Price in addition to 20% VAT on Buyer’s Premium.

Sold for

£24,000

Starting price

£4800