Auction: 23002 - Orders, Decorations and Medals

Lot: 34

'Just then I got a musket-ball through my right knee, and another in the shin, and my horse had three bullet wounds in the neck. Man and horse were bleeding so fast that Marsh begged me to fall out; but I would not, pointing out that in a few minutes we would be into them, and so I sent my spurs well home and faced it out with my comrades.

It was about this time that Sergeant Talbot had his head clean carried off by a round shot, yet for about thirty yards further the head-less body kept the saddle.

My narrative may seem barren of incidents, but amid the crash of shells and the whistle of bullets, the cheers and the dying cries of comrades, the sense of personal danger, the pain of wounds and the consuming passion to reach an enemy, he must be an exceptional man who is cool enough and curious enough to be looking serenely about him for what painters call “local colour.” I had a good deal of “local colour” myself, but it was running down the leg of my overalls from my wounded knee.'

Wightman on the Charge up the 'Valley of Death' at Balaklava: he would have the opportunity to add plenty more 'colour' before the day was out.

The important Charge of the Light Brigade pair awarded to Private J. W. Wightman, 17th Lancers, later Ensign, Military Train

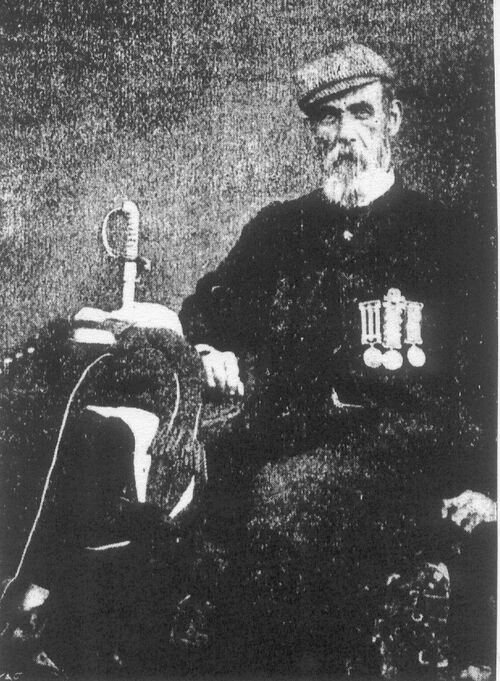

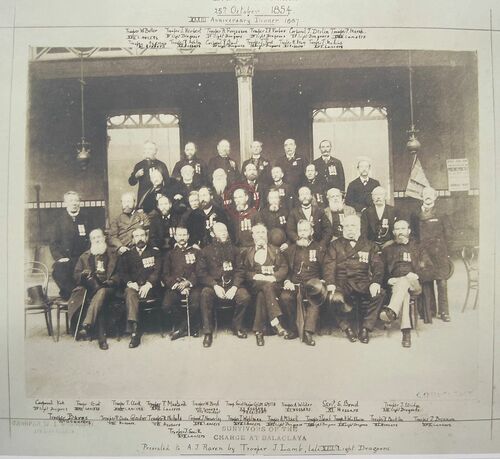

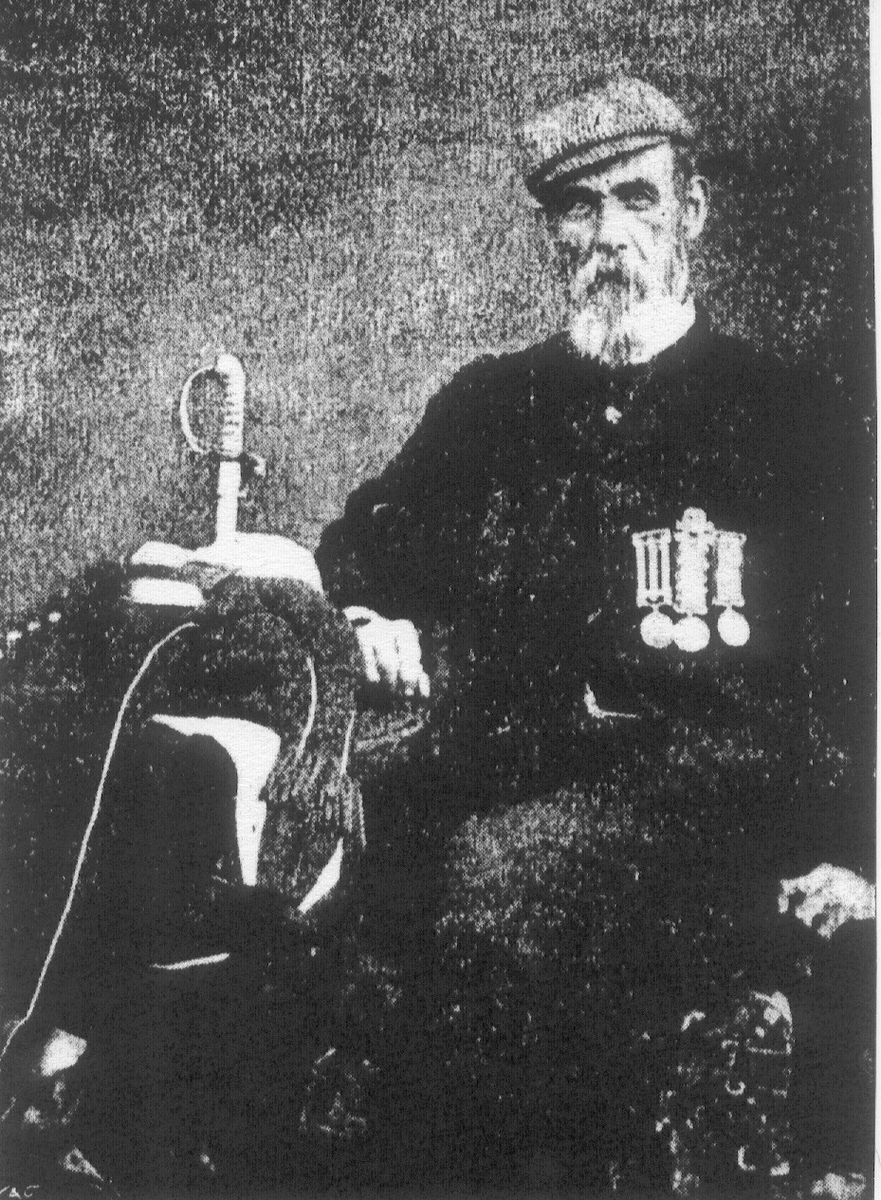

Wightman left one of the finest first-hand accounts of the events of that famous day, being severely wounded in no less than 13 places, taken a Prisoner of War and being given the most prominent central position in Caton Woodville's celebrated painting

Crimea 1854-56, 3 clasps, Alma, Balaklava, Sebastopol (J. Wightman. 17th Lancers.), officially re-impressed naming; Turkish Crimea 1855, British die (J. W. Wightman. 17th Lancers), contemporarily engraved naming, this second plugged and fitted with Crimea suspension, wear overall, fine but an important Pair nonetheless (2)

Provenance:

Glendinning's, December 1988.

Another group, with an Indian Mutiny in addition, was sold at Glendinning's in February 1917 February 1917 (listed as with 'four bars' and a 'Central India' clasp to Indian Mutiny, to which he was not entitled) & Sotheby's in November 1986 (now with one less clasp to the Crimea - this described as having 'engraved' naming - and the Mutiny without clasp).

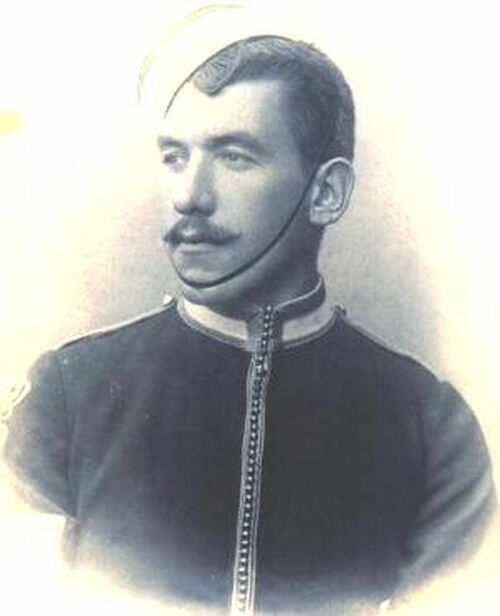

James William Wightman was born at York on 23 November 1834, son of Corporal Wightman, 7th Lancers and grandson of Lieutenant Wightman, Royal Horse Artillery, who was a Military Knight of Windsor. Young Wightman enlisted in the 17th Lancers at Hounslow on 19 October 1852. It was to be an action-packed few years for him, sharing in the famous Charge of the Light Brigade, in the process writing himself into history. He is confirmed by all the published rolls and his memoirs give a unique account of the action and his part of that famous day:

'And I remember as if it were yesterday Cardigan's figure and attitude, as he faced the Brigade and in his strong hoarse voice gave the momentous word of command, 'The Brigade will advance! First Squadron of 17th Lancers direct!'...his long military seat was perfection on the thoroughbred chestnut 'Ronald' with the white stockings on the near hind and fore, which my father, his old Riding-Master, had broken for him...the trumpeter sounded the 'Walk' after a few horse lengths came 'Trot', I did not hear the 'Gallop' but it was sounded. Neither voice nor trumpet, so far as I know, ordered the 'Charge'...we had not broke into the charge pace when poor old Jim Lee, my right-hand man on the flank of the Regiment, was all but smashed by a shell; he gave my arm a twitch, as with a strange smile on his worn old face he quietly said 'Domino! chum' and fell out of the sadly. His old grey mare kept alongside of me for some distance, treading on and tearing out her entrails as she galloped, till at length she dropped with a strange shriek.

Next beyond Peter Marsh was Private Dudley. The explosion of a shell had swept down four or five men on Dudley's left, and I heard him as Marsh if he had noticed 'what a hole that bastard shell made' on his left front. 'Hold your foul-mouthed tongue swearing like a blackguard, when you may be knocked into eternity next minute!'

Just then I got a musket-ball through my right knee, and another in the shin, and my horse had three bullet wounds in the neck. Man and horse were bleeding so fast that Marsh begged me to fall out; but I would not, pointing out that in a few minutes we would be into them, and so I sent my spurs well home and faced it out with my comrades. It was about this time that Sergeant Talbot had his head clean carried off by a round shot, yet for about thirty yards further the head-less body kept the saddle. My narrative may seem barren of incidents, but amid the crash of shells and the whistle of bullets, the cheers and the dying cries of comrades, the sense of personal danger, the pain of wounds and the consuming passion to reach an enemy, he must be an exceptional man who is cool enough and curious enough to be looking serenely about him for what painters call “local colour.” I had a good deal of “local colour” myself, but it was running down the leg of my overalls from my wounded knee.'

Wightman had also been witness to the death of Captain Nolan:

'I saw the shell explode of which a fragment struck him. From his raised sword-hand dropped the sword. The arm remained upraised and rigid, but all the other limbs so curled in on the contorted trunk as by a spasm, that we wondered how for the moment the huddled form kept the saddle. The weird shriek and the awful face haunt me now to this day, the first horror of that ride of horrors.'

They were now up to the Russian guns, Wightman could see Cardigan in front of him before the great clouds of smoke and the barrels of the enemy. Wightman went through the smoke and with a leap from him mount, was out the other side. He found himself alone and Cardigan '...in the midst of a knot of Cossacks' but came across Lieutenant Maxse. Lieutenant Maxse, badly wounded and clinging to his horse's mane, cross his front, and that he had called out, 'For God's sake, Lancer, don't ride over me.' Maxse himself said later that he had cut at two Russians around the guns as he passed through and one of them had pointed a pistol at him, but he was much too preoccupied to notice whether he had fired. Wightman continued on to follow Cardigan and suffered a lance wound in the left thigh from a Cossack, who he then slayed. The enemy were closing in and he rode towards Private Samuel Parkes who won his Victoria Cross with the 4th Hussars that day, who was supporting Trumpet-Major Crawford. Wightman continues:

'A body of Russian Hussars blocked out way. Morley, roaring Nottingham oaths by way of encouragement, led us straight at them, and we went through and out the other side as if they had been made of tinsel paper. As we rode up the valley, pursued by some Hussars and Cossacks, my horse was wounded by a bullet in the shoulder and I had hard work to put the beast along. Presently we were abreast of the Infantry who blazed into our right as we went down; and we had to take their fire again, this time on our left...not many got back...my horse was shot dead, riddled with bullets. One bullet struck me on the forehead, another passed through the top of my shoulder; while struggling out from under my dead horse a Cossack standing over me stabbed me with his lance once in the neck near the jugular, again, above the collar-bone, several times in the back, and once under the short-rib; and when, having regained my feet, I was trying to draw my sword, he sent his lance through the palm of my hand. I believe he would have succeeded in killing me, clumsy as he was, if I had not wounded him for the moment with a handful of sand. Fletcher at the same time lost his horse, and it seems, was wounded. We were very roughly used. The Cossacks at first hauled us along by the tails of our coatees and our haversacks. When we got on foot they drove us using their lance-butts into our backs to stir us on. With my shattered knee and the other bullet wound on the shin of the same leg, I could barely limp, and good old Fletcher said "Get on my back, chum!". I did so and then found that he had been shot through the back of the head.'

So it was that Wightman was wounded in that legendary action in no less than 13 places. He was taken Prisoner of War and wrote to his parents on 9 November:

'My Dear Father and Mother,

I am sorry to relate to you that I am no longer with the British Army. We had a very severe engagement on the 25th of October and I got severely wounded in seven places, and was taken prisoner; but, thank God, they are all Christians, and the could not behave kinder. I am not the only one in the corps; there are twelve of us and Adjutant. Including the Light Brigade, there are about thirty-six. The inhabitants behave very kindly indeed, they bring us cakes, tobacco and everything you can mention; our own countrymen could not treat us better, and whenever I meet a Russian I shall always treat them well and with respect. You will see all particulars in the newspapers shortly, and very likely the names of the prisoners. I can say no more at present but wish you may have a merry Christmas and a happy New Year, and believe me to be your most affectionate son, James Wightman.'

He was eventually repatriated, having had the musket ball removed from his right thigh by a Russian surgeon, aboard the Odessa in Autumn 1855. Wightman would serve in India (Medal without clasp), having been promoted Corporal on 1 September 1856 and Sergeant on 7 September 1857. Transferred to the 21st Hussars on 21 February 1864, he was commissioned Ensign in the Military Train in November 1866 and resigned his commission in October 1868.

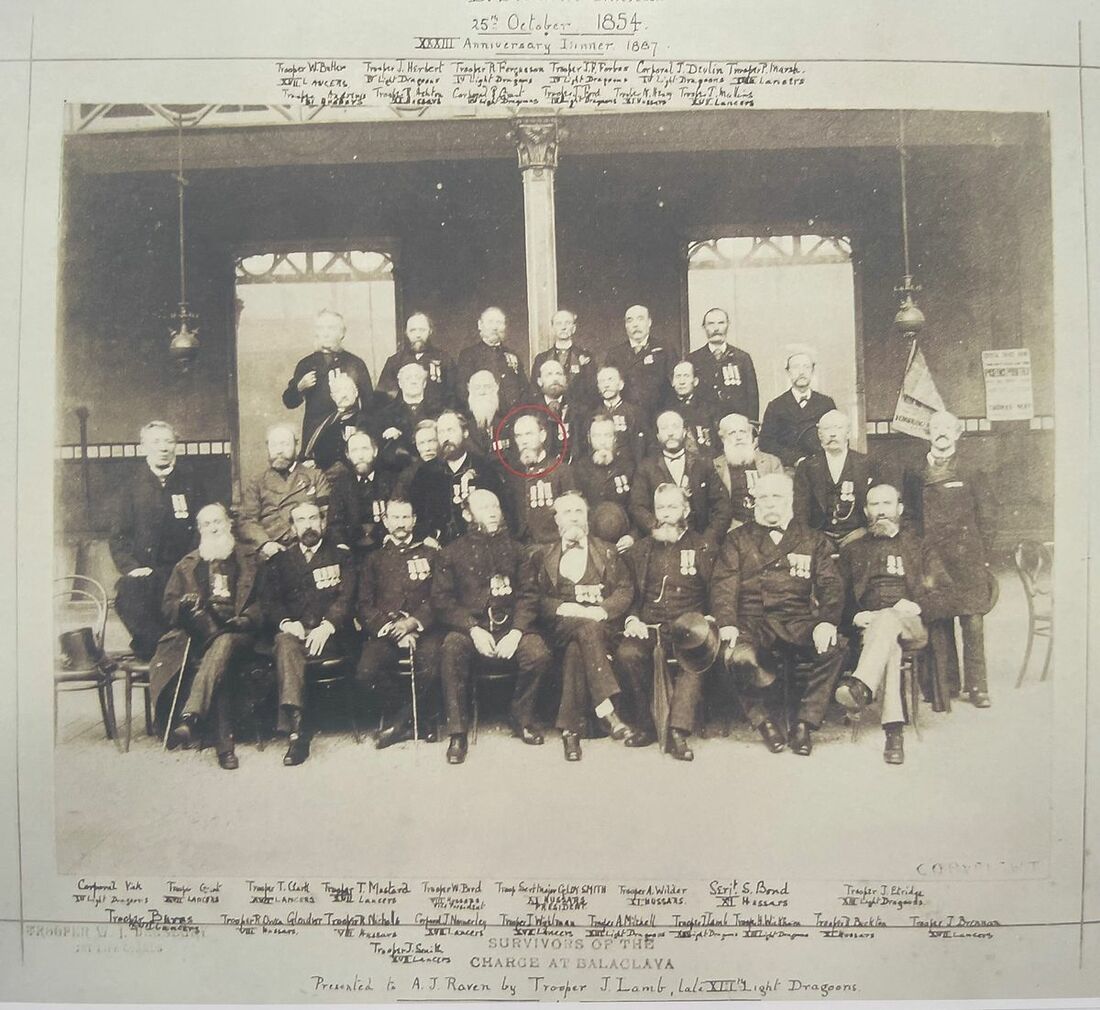

He was undoubtedly one of the most celebrated veterans of the Charge, attending the dinners of 1887, 1890, 1892, 1894, 1895, 1897 & 1899. He was in receipt of two pensions for his service and was given the most prominent central position for the famous painting of the Charge of the Light Brigade by Richard Caton Woodville. Wightman lived at 8 Durham Place, Kensington and latterly at 47 Seagrave Road, Fulham, where he died on 17 February 1907. He is buried in the Brompton Road Cemetery (grave No. 133750).

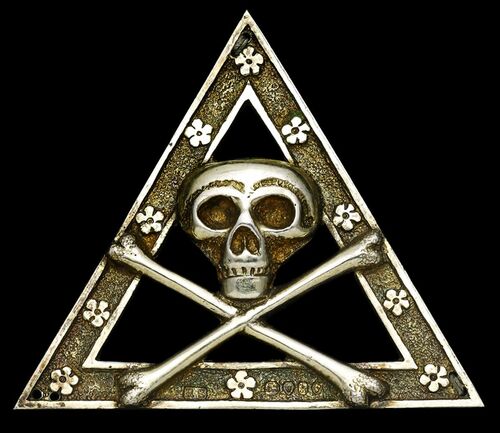

Sold together with the finely tooled silver-gilt (Hallmarks for London 1865, maker's initials 'RS') 'skull and cross bones' Badge, which has always accompanied the Medals and a good file of copied research.

Subject to 20% VAT on Buyer’s Premium. For more information please view Terms and Conditions for Buyers.

Sold for

£13,000

Starting price

£4500