Auction: 23002 - Orders, Decorations and Medals

Lot: 12

The rare and important Waterloo Medal awarded to Lieutenant-Colonel G. Colquitt, 1st Foot Guards, a veteran of the Peninsular War who commanded a Company of his Battalion throughout the Hundred Days campaign and was in the thick of the fighting at the battles of Quatre Bras and Waterloo, at which latter occasion his name has gone down in history for picking up a live French artillery shell and throwing it outside his Square before it exploded, thereby saving many lives; a tremendously brave act amongst many upon that famous day

Waterloo 1815 (Lt.-Col. Goodwin Colquett, 2nd Batt. Grenad. Guards.), suspension partly replaced with contemporary silver post, original steel ring, first and last letters of naming partially obscured by suspension, obverse with minor contact marks, good very fine

[C.B.] London Gazette 16 September 1815

It should be noted that, though his surname appears in most published sources as Colquitt, the Waterloo Medal Roll notes him as Colquett and his Medal - entirely as issued - is named thusly.

Early Life and Adventures in the Peninsula

Goodwin Colquitt was born in 1786 and commissioned Ensign in the 1st Foot Guards on 28 December 1803: his first taste of active service came when the 1st Battalion of the regiment were deployed to Sicily from 1806-07, returning to England in that latter year. Colquitt was promoted Lieutenant and Captain (a double-rank specific to the Foot Guards) on 15 September 1808; in this capacity he saw active service during the Peninsular War, with his brother John Scrope Colquitt also an officer in the same regiment.

In early 1810 Colquitt embarked for Cadiz and on 5 March 1811 participated in the Battle of Barossa, an Anglo-Iberian attempt to break the siege of the city. The allied force, commanded by General Sir Thomas Graham (one of Wellington's most trusted subordinates), was landed at Tarifa and attempted to attack and destroy the French siege works from the rear: however, Graham's opposite number Marshal Victor redeployed his forces and was ready for the intended attack. Advancing inland, Graham's force was attacked in strength and the vital Barrosa Ridge captured with little effort due to a precipitate withdrawal of five battalions of Spanish infantry: the 530 men of Lieutenant-Colonel Browne's 'Flank Battalion' were ordered to retake the crest - they were opposed by a French Division under General Francois Ruffin numbering some 4,000 together with a battery of artillery. The outcome was predictable; with increasing casualties Browne's men could advance no further and sought cover amongst the casualty-strewn forward slope. The French, however, declined to advance as Ruffin could see a British force coming to Browne's aid - the Guards Brigade under Brigadier-General William Dilke; Lieutenant and Captain Goodwin Colquitt being one of that number. Forming up at the base of the ridge, Dilke's Brigade advanced rapidly and gained the crest without suffering severe casualties: the Guards had, however, become disorganised and now Ruffin launched four battalion columns of infantry at the un-formed British line in an attempt to overwhelm them. Despite this, in a scene to be oft-repeated during the Peninsular War the British infantry stood firm and subjected the French columns to a tremendous volume of well-directed musket fire; even the addition of two further French battalions into the attack did little to alter the outcome of the engagement, which ended in the British forcing the French off the hill in a headlong rout and the mortal wounding of General Ruffin. Another man wounded that day was Goodwin Colquitt, almost certainly on the spot of that dreadful exchange of musketry which decided the battle in the allies' favour.

Returning home recuperate, Colquitt re-joined the regiment in the Peninsula in March 1813 - perhaps a stroke of good fortune as the previous few months had seen the 1st Battalion ravaged by sickness and disease. At the end of June that year, the unit was finally in a fit state to march up to join Wellington's main army in northern Spain; though they remained in reserve for the last battles of the Peninsular War, Colquitt appears to have been something of a correspondent and left a few interesting glimpses of his experiences of campaigning:

'August 18th

We this day joined the First Division in Camp near Oyarzun; after a march of between five and six hundred miles our brigade occupied the right of the position; next to us was the 2nd Brigade of Guards, then a Brigade of German Infantry of the Line, and on the left some troops of that Legion. I dined with Watson of the Third Regiment and in the evening walked to the top of an eminence from which we could plainly perceive the whole of the French position in our front, said to consist of about eight thousand men, occupying huts erected on the heights. On the other side of the Bidassoa which here forms the boundary between Spain and France, the atmosphere was not very clear, but we saw the towns of Hendaye, Urrugne and the situation of St. Jean de Luz. It was a most interesting moment to join the Army when the first advancing movements would bring us on the sacred territory of France (a favourite expression of the Moniteur). At that period it might be called so since foreign troops had only approached its frontiers (during the Revolutionary War) to be driven back to their very capitals.' (The Diary of Captain Colquitt, 1813, Journal for the Society for Army Historical Research, Autumn 1938, Vol. 17, No 67, pp. 157-162, refers).

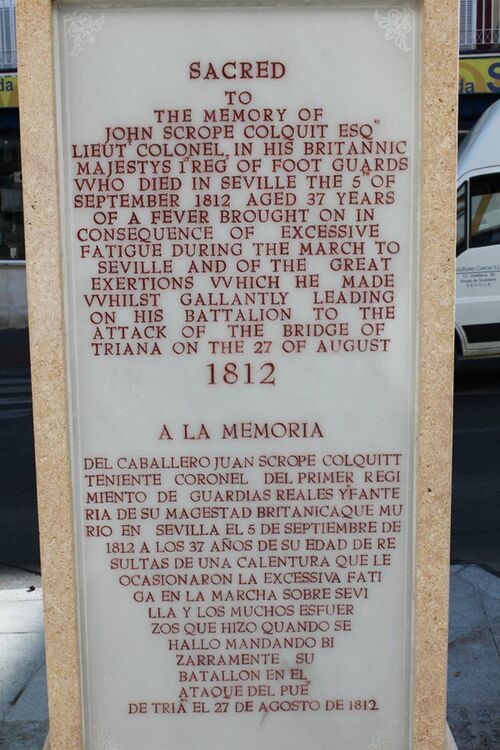

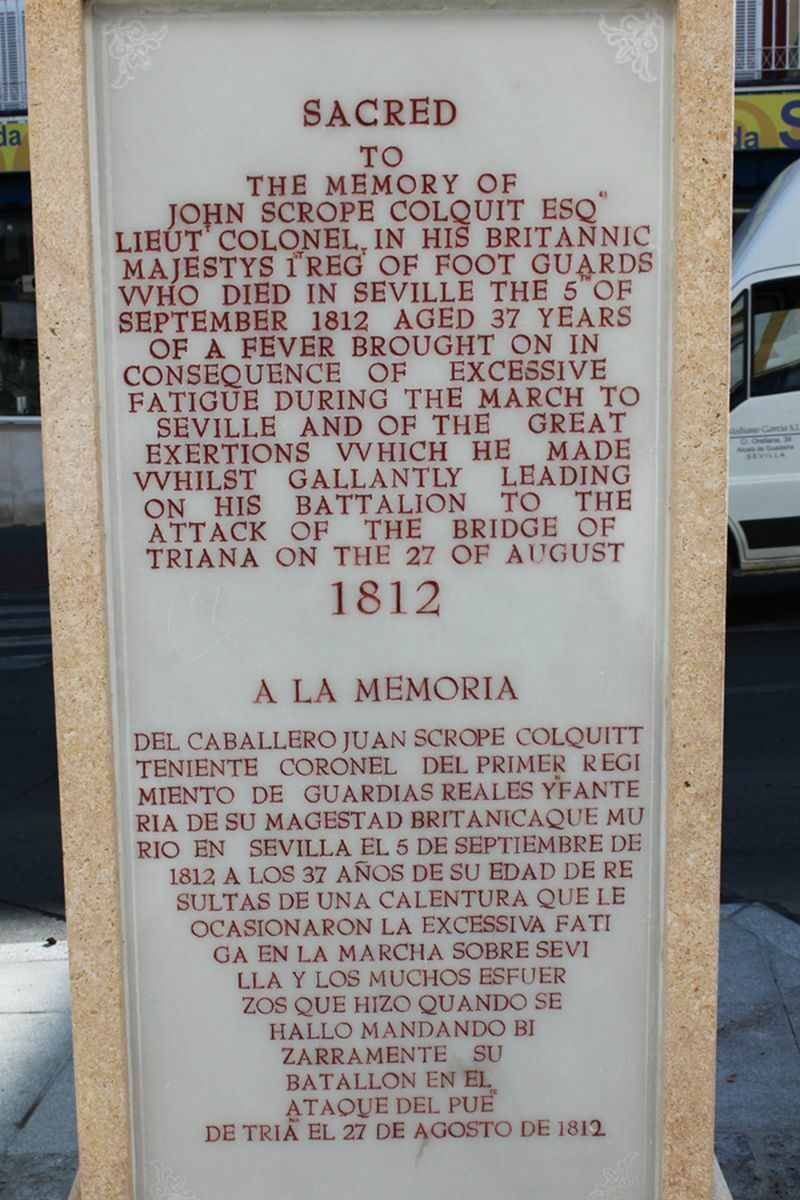

Though these movements saw Colquitt through to the conclusion of the War, before moving on mention must be made of his brother, John. Fighting side-by-side with Goodwin, after Barrosa John Colquitt returned to Cadiz and on 27 August 1812 participated in the liberation of Seville, leading his men under fire at the crossing of the Triana Bridge - shortly after however, he fell ill and died on 4 September. In May 2012, a grand and impressive memorial to John Scrope Colquitt was unveiled in Seville which was attended by descendants of the Colquitt family, senior members of the Association of the English Cross, and current representatives of the Grenadier Guards.

Waterloo and a Brave Act

Returning home at the conclusion of the Peninsular War, on 25 July 1814 Goodwin Colquitt was promoted Captain and Lieutenant-Colonel and assumed command of a Company within the 2nd Battalion 1st Foot Guards. Upon Napoleon Bonaparte's escape from Elba and return in triumph to France, the allied nations decided upon his defeat once and for all and the Allied force then being formed in the Low Countries under the Duke of Wellington included both 2nd and 3rd battalions of the 1st Foot Guards, comprising the 1st British Brigade in Major-General George Cooke's 1st British Infantry (Guards) Division. On the eve of Napoleon's advance into Belgium, this formation was stationed south-west of Brussels some distance from the French direct route to the city; upon receiving news to concentrate at Quatre Bras, Wellington's forces immediately rushed to do battle with the enemy. Similarly to his writing of campaigning in Spain, Colquitt penned a fascinating personal account of the opening of the campaign and the Battle of Quatre Bras:

'16 June 1815 - Night March to Quatre Bras

We were suddenly moved from Enghien, where we had remained so many weeks in tranquility, on the night of the 15th instant, or rather the morning of the 16th at three o'clock. We continued our march through Braine-le-Comte, (which had been the Prince of Orange's headquarters) and from thence to Nivelles, where we halted and the men began making fires and cooking. During the whole of this time, and as we approached the town, we distinctly heard a constant roar of cannon; and we had scarcely rested ourselves, and commenced dressing the rations, which had been served out at Enghien, when an aid-de-camp from the Duke of Wellington arrived, and ordered us instantly under arms, and to advance with all speed to Les Quatres Bras, where the action was going on with the greatest fury, and where the French were making rapid strides towards the object they had in view, which was to gain a wood, called 'Bois de Bossu', a circumstance calculated to possess them of the road to Nivelles, and to enable them to turn the flank of the British and Brunswickers, and to cut off the communication between them and the other forces which were coming up. The order was, of course, instantly obeyed; the meat which was cooking, was thrown away; the kettles &c packed up, and we proceeded, as fast as our tired legs would carry us, towards a scene of slaughter, which was a prelude well calculated to usher in the bloody tragedy of the 18th.'

'16 June 1815 - Quatre Bras

We marched up towards the enemy, at each step hearing more clearly the fire of musquetry; and as we approached the field of action, we met constantly wagons full of men, of all the various nations under the duke's command, wounded in the most dreadful manner. The sides of the road had a heap of dying and dead, very many of whom were British; such a scene did, indeed, demand every better feeling of the mind to cope with its horrors; and too much cannot be said in praise of the division of Guards, the very largest part of whom were young soldiers, and volunteers from the militia, who had never been exposed to the fire of an enemy, or witnessed its effects. During the period of our advance from Nivelles, I suppose nothing could exceed the anxiety of the moment, with those on the field. The French, who had a large cavalry and artillery, (in both of which arms we were quite destitute, excepting some Belgian and German guns) had made dreadful havock in our lines, and had succeeded in pushing an immensely strong column of tirailleurs into the wood I have before mentioned, of which they had possessed themselves and had just began to cross the road, having marched through the wood, and placed affairs in a critical situation, when the Guards luckily came into sight. The moment we caught a glimpse of them, we halted, formed, and having loaded, and fixed bayonets, advanced; the French immediately retiring; and the very last man who attempted to re-enter the wood, was killed by our grenadiers. At this instant, our men gave three glorious cheers, and, though we had marched fifteen hours without anything to eat or drink, save the water we had procured on the march, we rushed to attack the enemy. This was done by the 1st Brigade, consisting of the 2nd and 3rd battalions of the first regiment; and the 2nd Brigade, consisting of the 2nd battalion of the Coldstream and third regiment, were formed in a reserve along the chaussee. As we entered the wood, a few noble fellows, who sunk down overpowered with fatigue, lent their voices to cheer their comrades. The trees were so thick, that it was beyond anything difficult to effect a passage. As we approached, we saw the enemy behind them. Taking aim at us; they contested every bush, and at a small rivulet running through the wood, they attempted a stand, but could not resist us, and we at last succeeded in forcing them out of their possessions. The moment we endeavoured to go out of this wood (which had naturally broken us), the French cavalry charged us; but we at last found the third battalion, who had rather skirted the wood, and formed in front of it, where they afterwards were in hollow square, and repulsed all the attempts of the French cavalry to break them. Our loss was most tremendous, and nothing could exceed the desperate work of the evening; the French infantry and cavalry fought most desperately; and after a conflict of nearly three hours (the obstinacy of which could find no parallel, save in the slaughter it occasioned), we had the happiness to find ourselves complete masters of the road and wood, and that we had at length defeated all the efforts of the French to out-flank us, and to turn our right, than which nothing could be of greater moment to both parties.

General Picton's superb division had been engaged since two o'clock pm was still fighting with the greatest fury; no terms can be found sufficient to explain their exertions. The fine brigade of highlanders suffered most dreadfully, and so did all the regiments engaged. The gallant and noble conduct of the Brunswickers was the admiration of everyone. I myself saw scarcely any of the Dutch troops; but a regiment of Belgian light cavalry held a long struggle with the famous cuirassiers, in a way that can never be forgotten; they, poor fellows, were nearly all cut to pieces. The French cuirassiers charged two German guns, with the intent of taking them to turn them down the road on our flank. This charge was made along the chaussee running from Charleroi to Brussels; the guns were placed near the farm-house of Les Quatre Bras, and were loaded, and kept till their close arrival. Two companies (I think of highlanders) posted behind a house and dung hill, who flanked the enemy on their approach, and the artillery, received them with such a discharge, and so near, as to lay (with an effect like magic) the whole head of the column low; causing it to fly, and be nearly all destroyed. We had fought till dark; the French became less impetuous, and after a little cannonade they retired from the field. Alas! When we met after the action, how many were wanting among us; how many who were in the full pride of youth and manhood, had gone to that bourn, from whence they could return no more.' (The Waterloo Archive, Vol. IX, British Sources, Ed. Gareth Glover, 2020, p. 118-120, refers).

The Battle of Quatre Bras had been fought to a stalemate, with neither the allies nor French remaining masters of the field. Wellington, however, aware of his tactical disadvantage decided to withdraw to the much stronger position at Mont St. Jean - otherwise known as Waterloo. The retreat was carried out under cover of a ferocious rainstorm, which helped the allies and hindered the French; in the general dispositions of the 18 June 1815, Cooke's division was positioned at the right-centre of Wellington's line - the place of honour as befitted the Guards, and an area of the battlefield which was to see a significant amount of action, with Colquitt personally seeing more than his fair share.

"Now Maitland: Now's Your Time!"

Whilst the 2nd Battalion 1st Foot Guards were not engaged as other battalions of the Foot Guards in the heroic defence of the chateau of Hougoumont, nevertheless they held the line with solid determination - for much of the time just below the reverse slope in 'square' formation to resist the all-round assault of French cavalry: indeed they were initially charged at approximately 4pm by the 'Red Lancers' of the Imperial Guard, a foe with a reputation for their veteran status. Ensign Rees Howell Gronow, a fellow Foot Guards officer (and famous Regency 'Dandy') later wrote:

'Not a man present who survived could have forgotten in after life the awful grandeur of that charge. You perceived at a distance what appears to be an overwhelming, long moving line, which, ever advancing, glittered like a stormy wave of the sea when it catches the sunlight. On came the mounted host until they got near enough, whilst the very earth seemed to vibrate beneath their thundering tramp. One might suppose that nothing could have resisted the shock of this terrible moving mass. They were the famous cuirassiers, almost all old soldiers, who had distinguished themselves on most of the battlefields of Europe...'

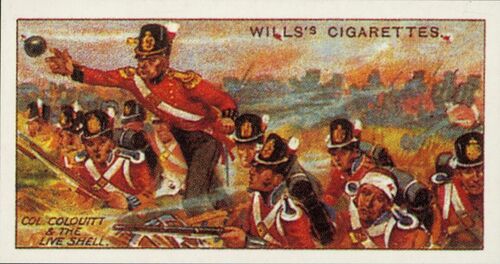

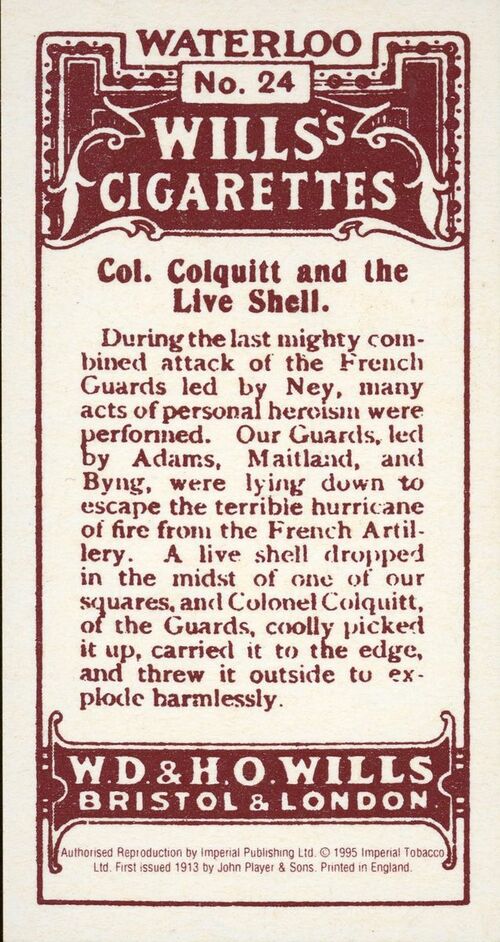

It was during this period formed in square that Colquitt performed an act of great bravery which, it is fair to say, had the Victoria Cross existed at the time he would likely have received. Whilst standing with a fellow officer a live French artillery shell sailed over the ridge and landed in the mud, its fuse still fizzing and spluttering. Without a second's thought, Colquitt picked it up and launched it over the heads of his men - where it subsequently exploded without causing injury or harm. Ensign Gronow later wrote of this incident in his memoirs, recalling:

'During the terrible fire of artillery which preceded the repeated charges of the cuirassiers against our squares, many shells fell amongst us. We were lying down, when a shell fell between Captain (afterwards Colonel) Colquitt and another officer. In an instant Colquitt jumped up, caught the shell as if it had been a cricket ball, and flung it over the heads of both officers and men, thus saving the lives of many brave fellows.' (Recollections and Anecdotes: Being a Second Series of Reminiscences of the Camp, the Court, and the Clubs, Captain R.H. Gronow, 1863).

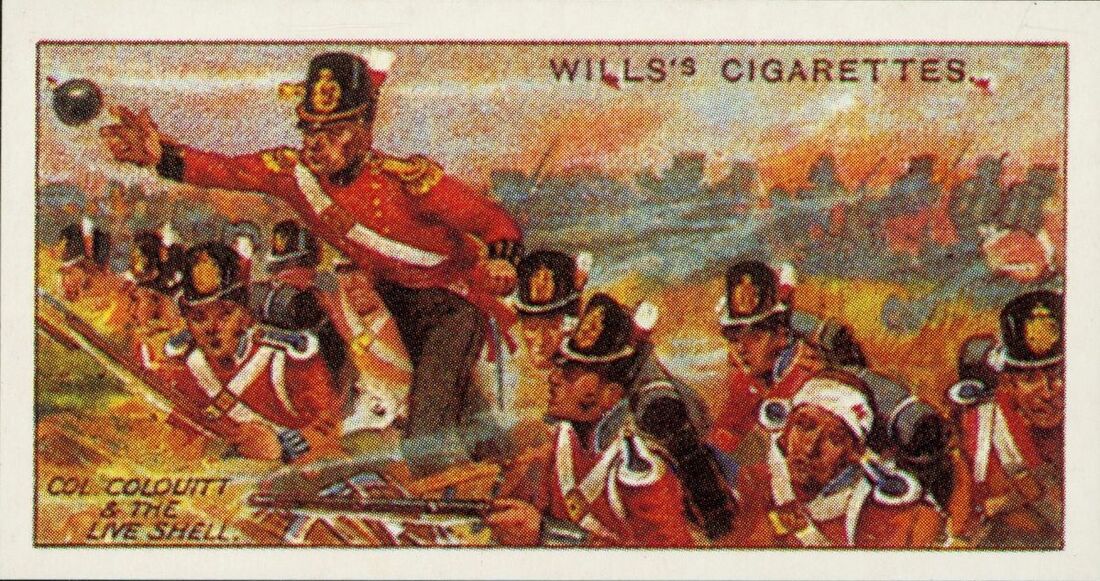

This feat of daring was subsequently immortalised as part of a set of Waterloo commemorative cigarette cards, published by Wills's, intended for release at the time of the centenary of the battle in 1915 - however due to the Great War (and possibly aided by the fact Britain and France were now allies) this set never entered production, though facsimile examples exist to this day.

Colquitt was further to share in the most famous episode in the history of the regiment, and the one credited with their re-titling (by Royal Proclamation) as the Grenadier Regiment of Foot Guards. Towards the end of the battle, when every other French assault on the Allied line had failed and with the ever-increasing numbers of Prussian troops appearing on Napoleon's right flank, the Emperor ordered the elite troops of his famous Imperial Guard forward; never before defeated in battle, by coincidence the three left-hand battalions of the Chasseurs of the Guard came into contact with their British equivalent. Advancing up the forward slope, their ranks thinned by Allied artillery fire, the French nevertheless crowned the ridge - this was one of the most crucial moments of the entire battle and as usual the Duke of Wellington himself was on-hand to ensure the outcome. Shouting out to the Brigade Commander, Major-General Maitland: "Now Maitland, now's your time!" the Foot Guards (who had been lying down to avoid the worst of the French artillery fire) rose up and delivered a thundering volley at a mere 25 metres range; over 20 per cent of the French assault went down in this one discharge alone.

The Foot Guards followed this up with a steady advance with the bayonet - their opponents began to waver, before disintegrating as the thin red line approached them. Undoubtedly, Colquitt would have heard first-hand Wellington's famous exhortation and been with his men throughout those historic moments - it is worthy of note that, as he ended the battle as the senior unwounded officer of the battalion, he may have been in command at this point and would certainly have been so in the immediate aftermath of the battle. Perhaps he too picked up a bearskin cap from the body of an expired opponent and took it back to London: it was one of these caps, together with the defeat of Napoleon's vaunted Imperial Guard, that so attracted the attention of the Prince Regent and inspired him to rename the regiment and change their headdress to the famous bearskin cap known throughout the world to this day. Possibly as testament to his gallantry on 18 June, Colquitt was made a Companion of the Order of the Bath later that year; in 1820 he sold his commission and retired from the service, sadly dying only a few years later in 1823.

Sold with a file of copied research, including the full Society for Army Historical Research journal article relating to Colquitt's Peninsular War diary and a modern reproduction of the Wills's card depicting his daring feat of bravery. For the Grant-of-Arms of his son, Goodwin Colquitt Craven, see Lot 159.

Subject to 20% VAT on Buyer’s Premium. For more information please view Terms and Conditions for Buyers.

Sold for

£20,500

Starting price

£9500