Auction: 23001 - Orders, Decorations and Medals

Lot: 329

'At 1615hrs the bomb struck the ship. The starboard wing of the glider-bomb hit the foremast; this turned inboard and downwards, then it hit No. 3 derrick and exploded on the port side of the hatch. The explosion was extremely violent, and debris was thrown to a tremendous height.

I was knocked over by the blast and was dazed for a few minutes. The Master on the bridge, the lookout on the monkey island and the Assistant Steward in the saloon were all killed instantly...The explosion shattered the bridge, chartroom, wireless room leaving them a complete shambles...fortunately the engine room was undamaged.'

Master Marshall, in his own words on the bomb which struck the M.V. Delius.

The outstanding O.B.E. group of five awarded to Master G. Marshall, Merchant Navy, decorated after Delius took a direct hit during convoy duties on 21 November 1943; after all their senior officers had been killed, having began the journey as Second Mate, Marshall assumed command and it was down to his cool actions that she was somehow saved, made it back into formation and their precious cargo made port

The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire, (O.B.E.) Officer's Civil Division, 2nd Type breast Badge, silver-gilt, in its Royal Mint case of issue; 1939-45 Star; Atlantic Star; Italy Star; War Medal 1939-45, in their box of issue, this named to 'Gordon Marshall, O.B.E., 229...Road, Caffrington Road, Hull' and with their Minister of Transport forwarding slip, confirming these '4' awards, ink a little faded on the box of issue, good very fine (5)

O.B.E. London Gazette 18 April 1944. In a joint citation with another O.B.E. for Gilbert Filshie, the Chief Engineer Officer and two B.E.M.'s:

'The ship, sailing in convoy, was attacked and hit by enemy aircraft. The Master and three of the crew were killed and fire immediately broke out on board. The steering gear had been put out of action but alternative gear was immediately connected up and the ship manoeuvred to regain her place in the convoy. Meanwhile a fire-fighting party was organised to deal with the fire, and their determined efforts kept it under control, although it could not be extinguished until the vessel reached harbour five days after the attack.

The Chief Officer displayed great courage and exceptional judgment throughout. When the Master was killed he immediately assumed command and set about the task of getting the ship back into position in the convoy. He organised the fire squad and saw that the injured were tended. It was undoubtedly greatly due to his determination, skill and leadership that the ship and her cargo were saved.

The Chief Engineer Officer showed courage and coolness of a high order. Mr Filshie's skill and co-operation, undertaken in difficult and dangerous circumstances, prevented the fire from assuming dangerous proportions and helped greatly in the saving of the ship. Carpenter Philpott and Boatswain Page showed courage and devotion to duty. They worked almost unceasingly at the pumps and were conspicuous in their fire-fighting efforts which were carried out without regard to their personal safety.'

Gordon Marshall was born at Hull on 18 December 1914 and was a Merchant Seaman by trade. He was the Chief Officer aboard the Delius when she was struck by a glider-bomb launched from a He117 of KG40. The Marsa had already been rounded upon and was eventually abandoned, whilst it was the turn of the Delius to be targeted, for she was only able to steam at a little over seven knots. The following account was offered by her Carpenter, Reginald Philpott, who earned a B.E.M. in the events which followed:

'Just before dawn on a Friday morning, we left a West of England port, bound for India, in convoy, and on our first Sunday at sea a man was lost overboard. Nobody saw him fall, and it was not until the ship astern put up the signal "man overboard" that it was noticed that he was missing. Each ship in line threw life-belts to him as they passed, but by the time the escort reached the spot, he had disappeared.

From that time onwards it seemed as though we had a hoodoo on board; nothing seemed to go right, even the food went bad as the refrigeration went wrong; however nothing else happened until we got into the Indian Ocean. It was at the end of the monsoon season and the weather was very hot when the chief steward was taken ill; after three days of lingering with this illness, which we took to be simply the effects of the heat, he appeared on deck at about 5 o'clock in the morning, lay down in a hammock that was stretched on the boat deck, and died. We were all shocked at this, and began to think that it really was an unlucky trip. We buried him at sea, and those readers who have seen a burial at sea, will agree with me when I say, that it was a very solemn occasion. We carried on from there to our port of discharge in India, and there our bad luck showed itself again.

All hands on board, with very few exceptions, fell ill with malaria or dysentery, or both. We managed to get over it however, and started for home again, wondering what else was in store for us. We were not left waiting long, because we had hardly arrived at the Suez Canal when the chief officer fell ill, and took to his bunk. On arrival at Port Said he was so bad it was decided to put him ashore to hospital. Little did we know that we would not see him again, for four hours after being admitted to hospital he died.

So we left Egypt minus three of our original crew, and fully convinced that fate was not on our side. We safely passed through the Mediterranean and out into the Atlantic Ocean. We had barely got clear of Gibraltar however, when a single enemy plane came out, and commenced to circle the convoy, keeping well out of range of our guns. Each night he would go away; but the following morning he was back. The fact that he did not attack us convinced us that he was only acting as a spotter for other planes or submarines. After some days like this, it was noted on one day that the plane was not to be seen, so we decided that this was the day for our final piece of bad luck.

Sure enough at about 3.15 p.m. the aircraft warnings sounded and we all took up our action stations. Being the ship's Carpenter, I was in the repair party, and so I took up my station with the Bosun on the boat deck. About nine planes came out and most of these got through to the convoy. They first attacked a ship that had dropped astern of the convoy a short distance, owing to some engine trouble; they dropped about ten bombs, of which only one scored a hit, but unfortunately that one was enough to sink her.

After this, the Delius, became the target, and as a bomber came towards us from the direction of the stern quarter, a strange thing happened. A small plane appeared to drop from the rear of the bomber, and gathering speed all the time, flew over the top of the bombers, circled and came at us. We were taken completely by surprise, and thought it was an R.A.F. fighter that had come to protect us. However, as it appeared to be making straight for us, we decided to take no chances, and our gunners fired at it, and scoring a direct hit, it exploded near the ship.

Then it dawned on us that this was Jerry's secret weapon, that we had heard rumours about, and was called a "shelic bomb". The advantage of this new bomb for the enemy, is that the parent plane can keep out of range of our guns, and direct his shelic bomb by radio control to whichever target he wishes. This he did to us, after we exploded the first bomb. He flew past and went towards another ship, launched his bomb, which turned around and came back at us.

As I said earlier, I was on the boat deck with the bosun, and with us was an ordinary seaman, and behind us was a gunner. As I saw the bomb coming I shouted to the others to take cover, and dived for a door leading into the funnel, which was the nearest cover available. I had hardly got there with these two seamen when the bomb landed on the foredeck. I could not move forward or back, but just stood swaying from side to side; the blast hit us from one side then the other, and we saw all kinds of sparks, lumps of wood, metal, and a thick cloud of smoke go past us on the deck. I could not quite realise that we had been hit until I saw that the bosun was badly wounded, and the gunner was staggering around holding his stomach.

The Bosun died while I was with him, and after seeing the gunner was being cared for by the first aid party, I went to the fore deck where the lamp trimmer was trying to put out the fire caused by the bomb when it struck No.3 hold. He was throwing burning bags and pieces of tarpaulin over the side, and after a few minutes we thought that everything was out. Then we saw smoke coming from another hole and we went to investigate, having been joined by other men by this time.

We discovered that it was just smoke coming along the top of the cargo in the shelter deck, so we commenced to cover up again. As we were doing so Jerry came back again and we all tried to find some hole to crawl into for protection, but he was only taking photographs of his handiwork, so we were all right.

We got back amidships to find that besides the bosun, our captain, a steward and an A. B. had been killed while quite a number of others were injured. We sent out a call for a doctor, and shortly afterwards one was transferred aboard. I would like to say here how very good and sympathetic the naval escorts were to us. Every so often a corvette would come as close as possible and ask us if there was anything we needed, and they supplied us with hoses, medical stores, and even cigarettes.

That night we discovered that a piece of hot shrapnel had gone down a ventilator to the lower hold and the cotton which was stowed there was on fire. So a few of us stood by all night, pumping water down the ventilator in a vain effort to extinguish the fire. Next morning came the job of burying our dead. I mentioned before how solemn it is to witness a burial at sea. Imagine it as we watched four of our shipmates, one after the other, go into the sea; men who just a few hours earlier had been very much alive.

Later we took on board three officers from the ship that had been sunk previously; they had volunteered to come on board to help us when they heard that we had only one officer left. And were they a help to us? Right here, I thank God for men like them, who although, they themselves had lost everything when their own ship was sunk, volunteered to go to the help of other comrades who needed help. They cheered us up with their wise-cracks and jokes, and at that time we needed their support, because besides the fire we discovered that the water we were pumping into the hold was lodging on the starboard side of the ship and was giving the ship a very bad list.

To make matters worse, a heavy sea came up which held the ship further over. It was so bad that none of us on board thought that she would right herself each time she rolled over. We were expecting her to turn right over, and had that happened not one of us would have been saved. The water in the hold had now penetrated into the steward's stores, entry into which was possible from the main deck.

So we started the portable pumps going to try and pump the water away and to right the ship. The trouble was, that the cargo of peanuts in the hold were floating round in the stores kept getting into the sucker of the pump, stopping the water from going out. As a result, at least one of us had to stay down there all the time to keep the suction clear. Some of us were down there at least eight hours at a time. So we carried on for the rest of the voyage, 1,000 miles to go, and the ship on fire with a very serious list to starboard, and with injured men on board.

At times the ship fell back from the convoy, but eventually managed to catch up and keep her station. The engineers in an effort to save her, drilled holes in the bulkhead between the engine room and No.3 hold, through which they pumped steam to help control the fire.

In spite of all this we managed to get the ship into a British port. We had no compasses, no degaussing gear, the steering gear was faulty, and two of the six cylinders of the engine were out of action. The ship was steered by the stars at night while making port.

I would like to point out that the bringing home of this ship from the point where we were bombed was entirely due to the 28-year-old Second Mate [Marshall], who was the only officer we had left. On the death of the Chief Petty Officer, he took over the job; and when the Captain died, he took over the Captain's position in command. It was owing to his endurance and good spirits that we were able to carry on.

To give an example, owing to the fact that the dining saloon was wrecked the officers and engineers had to take their meals in the P.O.'s mess, and the table was only meant for six men. Imagine the sight of 18 men eating in there. It was a common sight to see the officer in command of the ship, sitting on the deck with his plate on his knees, while apprentices and junior engineers were sitting at the table.'

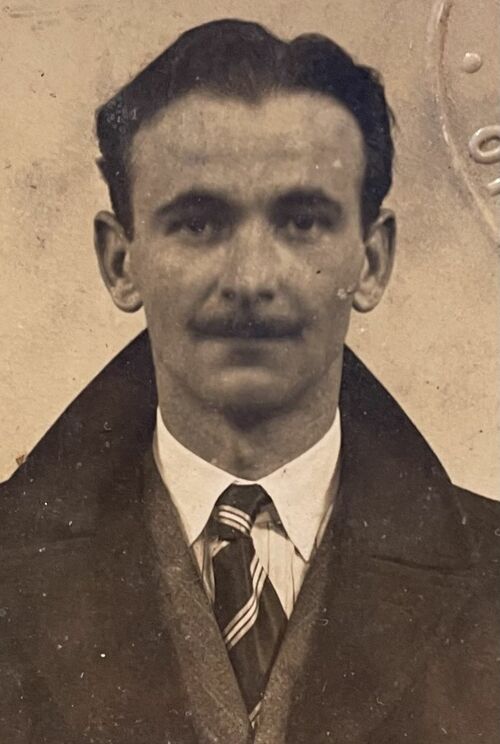

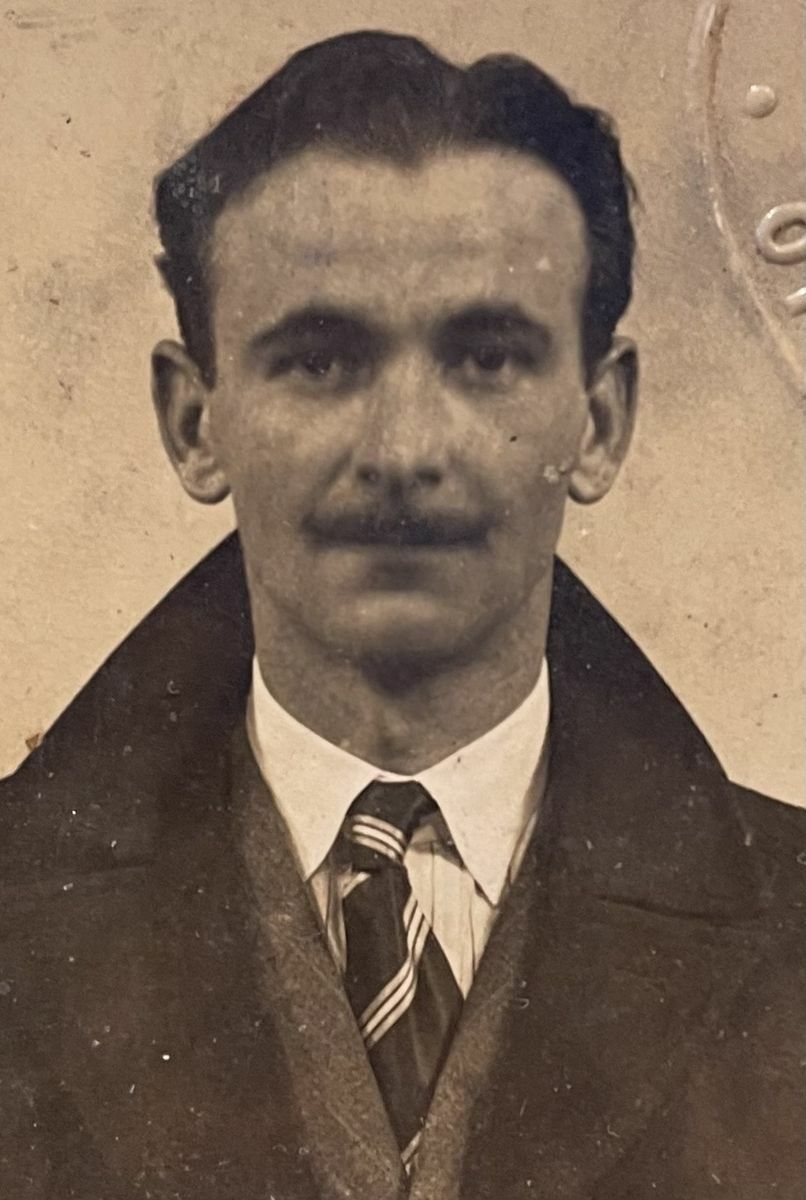

Marshall remained in the Merchant Navy until at least May 1971, by which point he had made Master, and died in March 2001; sold together with his British Seaman's Identity Card, including an image of the recipient and copied research.

Subject to 20% VAT on Buyer’s Premium. For more information please view Terms and Conditions for Buyers.

Sold for

£380

Starting price

£210