Auction: 23001 - Orders, Decorations and Medals

Lot: 232

'A little to my right I observed the wall was somewhat shattered by some chance shot of ours which had lobbed over the glacis. I got across from the top of one ladder to another, and with every exertion, I reached the top of the wall alone.

My favourite Havildar, which had thrown away his pike and drawn his sword, was endeavouring to ascend with me when he was shot, his blood flew completely over me. I had scarcely got my footing on the wall when a musket shot grazed my arm just above the wrist, a spear at the same instant wounded me in the shoulder, and a grenade (which they were showering upon us) struck me a severe blow on the breast, and hurled me almost breathless back from the wall.'

Lieutenant John Pester at the assault on Sarssney, 24 November 1802.

The outstanding - and unique - Army of India Medal awarded to Lieutenant-Colonel J. Pester, 2nd Bengal Native Infantry; a natural leader from the outset, Pester was at the forefront of some of the most challenging sieges faced by the British in India

During the Second Mahratta War General Lake was quick to recognise Pester's talents, assigning him important staff duties. At the sieges of Allighur and Deig Pester acted as liaison between the General's headquarters and the scene of heaviest fighting, while at the Battle of Delhi he rode at the head of his regiment and had his horse shot from under him

His diary, later published as War and Sport in India 1802-1806, forms a remarkable history of the campaign and is widely quoted in historical reference works

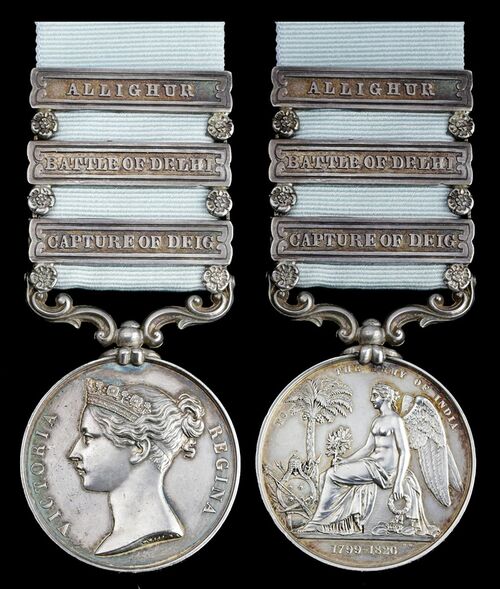

Army of India 1799-1826, 3 clasps, Allighur, Battle of Delhi, Capture of Deig (Lieut. J. Pester. 2nd N.I.), short-hyphen reverse, officially impressed naming, good very fine

Provenance:

London Stamp Exchange, September 1987.

Spink, December 1997.

John Pester was born at Odcombe, Somerset in 1778, the son of Emanuel and Peggy Pester. In 1800 he entered the East India Company's service as an Ensign in the 2nd Bengal Native Infantry. On 17 July 1801 he was advanced to Lieutenant.

In 1802 Pester's regiment was sent to the Doab, a marshy region at the confluence of the Ganges and Yamuna rivers. The Doab formed the extremity of Company territory in Bengal and its zemindars (land owners) were in open rebellion. They refused to pay taxes and defied the British from their ancient mud forts. The term 'mud fort' is really a misnomer, for mud walls were often reinforced with timber, were easy for a garrison to repair, and proved highly resistant to artillery fire.

The British army sent to pacify the Doab was commanded by General Lake, a veteran of the American Revolutionary War. Pester soon became adept at siege warfare, fighting in the British trenches at the mud forts of Sarssney, Bijighur and Kachaura. Lake encouraged his officers to keep diaries of their service, and Pester's description of the assault on Sarssney is especially vivid (see above). Pester led a storming party to Sarssney's walls and fought very bravely, incurring severe wounds. His diary reveals countless 'narrow escapes'.

Following this so-called 'Mud War', the 2nd Native Infantry were put on leave at Bareilly during the early months of 1803. With fellow officers, Pester indulged in tiger shooting and enjoyed all there was to offer. On 12 June the regiment arrived in cantonments at Shikohabad.

The Second Mahratta War, 1803-1805

Throughout the 18th century, a febrile confederacy of rulers from the Mahratta warrior caste held much of central and northern India. The region of Hindustan was presided over by the most powerful, Scindhia of Gwalior. In early 1803, during the Peace of Amiens, Napoleon sent 300 French officers to Scindhia with the aim of creating an 'Army of Hindustan'. These officers landed at Pondicherry in June 1803, and by September they had trained 11 battalions in European methods. General Perron, the most senior, established his headquarters in the ancient city of Koil and became Scindhia's regent. The British Governor-General Richard Wellesley sent General Lake with 10,500 men to counter the Mahratta threat. Deeply concerned by the French presence, he wrote to Lake:

'The effectual demolition of the French state, erected by M. Perron on the banks of the Jumna, [is] the primary object of the campaign'.

Lake's army left Cawnpore on 7 August and headed north-west along the Grand Trunk Road towards Koil. His force was composed almost entirely of Bengal Native Regiments, the only King's Regiments being the 76th Foot and the 8th, 27th and 29th Light Dragoons. Lake's 10,500 fighting men were encumbered by a vast baggage train; Thomas Seaton, one of Lake's aides during the campaign, estimated the camp followers to have numbered 100,000 (From Cadet to Colonel refers). Seaton complained that on a day's march, the advance guard would be in the next day's camp before the end of the train had left the previous camp. Owing to the severe heat, Lake's army would commence a march at 3 a.m. and then bivouac during the hottest time of day.

The 2nd Native Infantry marched from Shikohabad, joining Lake at Etah on 23 August. When war was declared on 26 August, Lake had already crossed into Mahratta territory.

'One of the most extraordinary feats that I have heard of in this country.'

- Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington, on the capture of Allighur

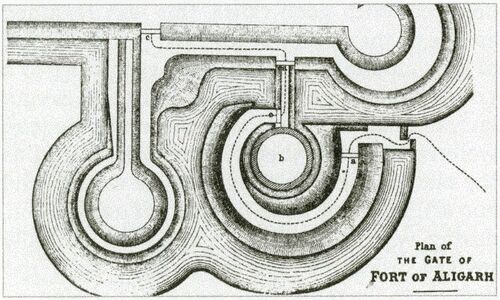

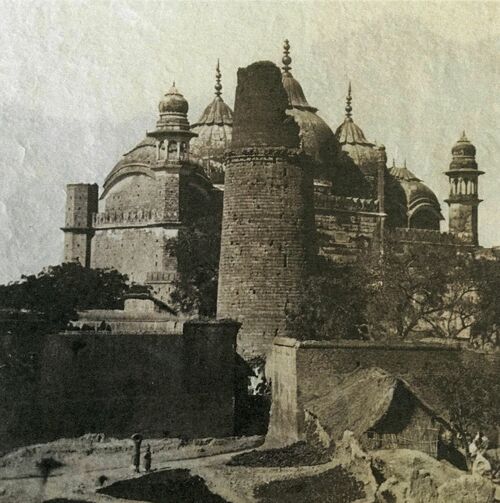

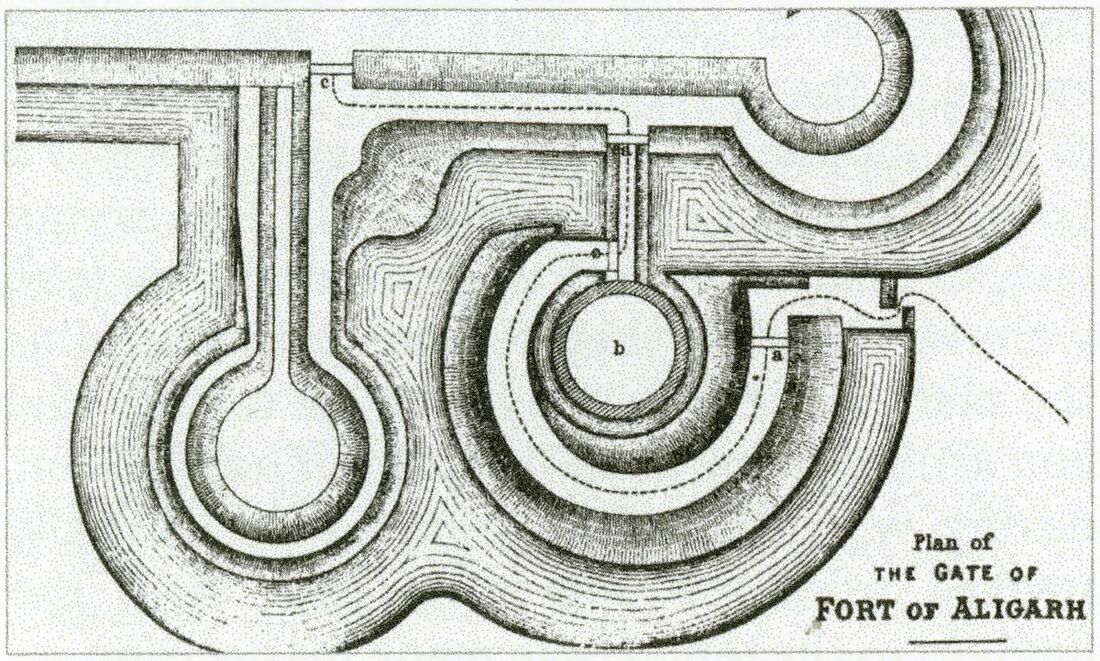

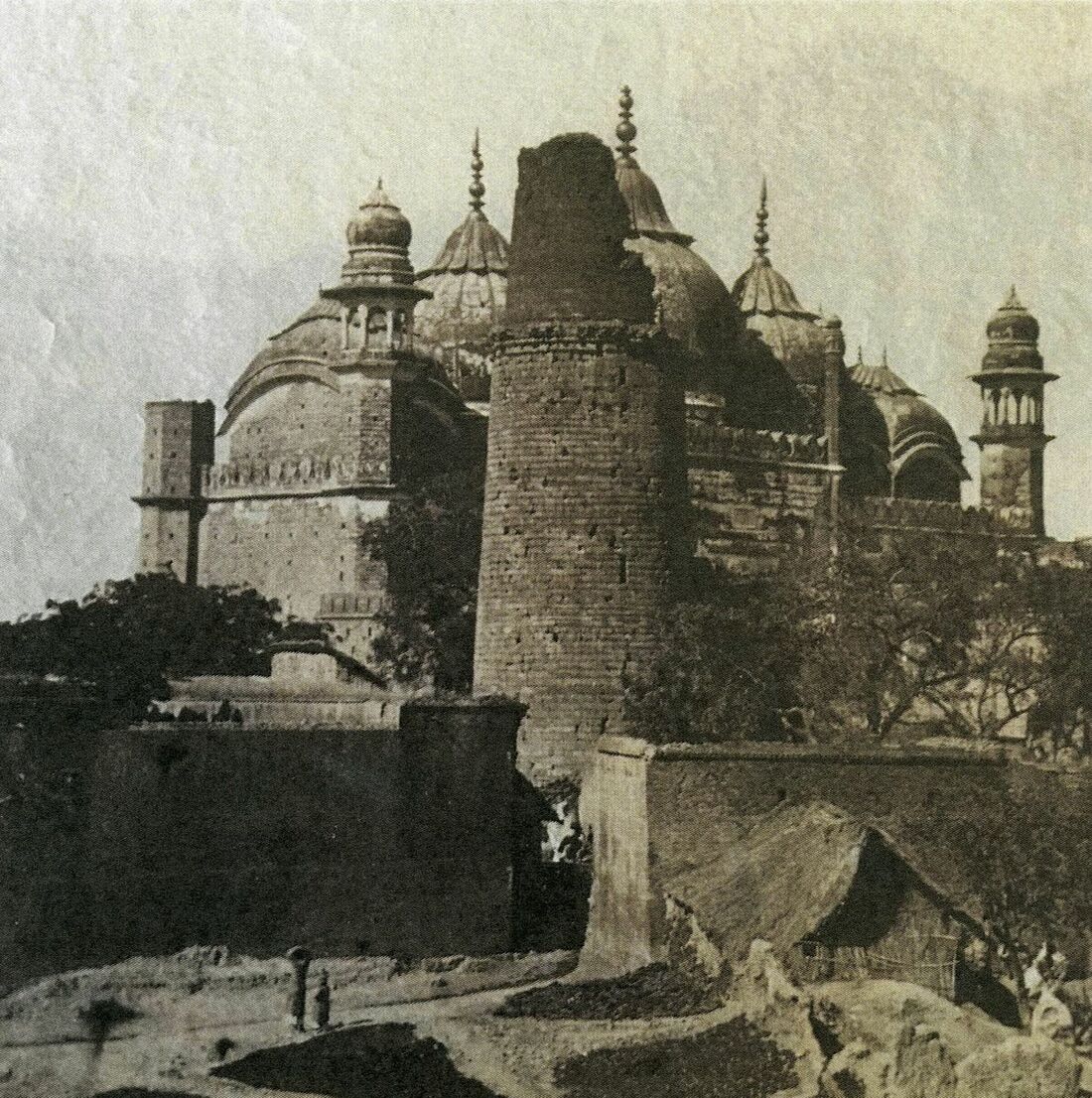

Protecting Koil was the imposing hill-fortress of Allighur. Allighur comprised circular towers with superb fields of fire, a good glacis, and a moat 32 feet deep and 200 feet wide. Any attacking force had to cross a narrow causeway over the moat, the garrison's 'killing zone'. Allighur had a large garrison with excellent Mahratta cannon, and sufficient provisions for a long siege.

Lake's advance guard neared Koil on 27 August, and saw General Perron's Mahratta army of 20,000 breaking camp just east of the city. Perron formed his army into a defensive line with a deep swamp protecting his front. Lake avoided a frontal assault and instead moved eastwards towards a Mahratta-held village guarding Perron's left flank. Pester takes up the story:

'The General did me the honour to send me repeatedly with orders during the affair, as his staff were all employed. I had my grey horse, Collector, shot through the neck in attacking the village with the advanced guard; he bled a good deal, but my other horses were with the line, in the rear, and I could not dismount him for nearly an hour after he was wounded.'

The village was taken after a sharp skirmish involving the 27th and 29th Light Dragoons, to whom Pester was seconded. Perron's Mahrattas withdrew to avoid being outflanked. As they streamed into Allighur they formed perfect targets for 6-pounder 'galloper guns' accompanying the British cavalry, and fell in their hundreds. The guns of Allighur attempted to respond, but could not find the range. Lake's army seized Koil and captured Perron's headquarters - by now an opulent estate with landscaped gardens known as the Sahib Bagh - before setting up camp south of Allighur. After five days of futile negotiations, Lake resolved to assault the fortress on 4 September. Pester states:

'Four companies of the 76th, with a proportion of men from the native corps, formed the storming party, and a quarter of an hour before day broke the whole advanced in silence and in a most steady becoming manner. I was ordered by the General to accompany the storming party, and to bring immediate information if any support should be required.'

Even with the cover of darkness, the stormers came under a murderous cross-fire as they ran over the causeway and reached the main gate. Attempts to place scaling ladders failed, as the Mahrattas had stationed pikemen atop the ramparts. The 6-pounder gun brought to blast in the main gate was found to have no effect, even when placed flush against the gates with a double powder charge. With great difficulty, a 12-pounder was wrestled into position. Pester continues:

'Never did I witness such a scene before the second gun could be hauled up; the sortie was become a perfect slaughter-house, and it was with the greatest difficulty that we dragged the gun over our killed and wounded. Nothing could exceed the determined gallantry with which our troops struggled under this most destructive fire. The enemy, too, fought desperately, and many of them actually stepped out upon our own ladders which were placed against the wall to meet our men ascending, but British valour prevailed.'

After the 12-pounder had fired five discharges, the gate finally gave way. The 76th poured through, followed by both battalions of the 4th Native Infantry. To their horror, the 'main gate' turned out to be merely an outerwork. Three more gates had to be forced, and each time the stormers had to manoeuvre the 12-pounder into place while subjected to withering cross-fire. Between the third and fourth gates lay a quarter of a mile of exposed glacis, over which the 76th led the British assault. Having lugged the 12-pounder all this distance at a terrible cost in lives, it was found insufficient to blast the final gate. Major MacLeod of the 76th then succeeded in forcing the postern gate, whereupon Company forces swept into the fort and inflicted immense slaughter on the Mahrattas. At least 2,000 Mahrattas were said to have died. Company losses were 59 killed, 212 wounded. Pester records that Lake permitted his army 'three hours of plunder'.

Advance on Delhi

On 5 September, reports reached Lake's army that some 5,000 Mahratta cavalry under a French officer had attacked the British baggage train at Shikohabad, setting fire to bungalows and taking hundreds of prisoners, including the wife of Lake's Aide de Camp. Lake now felt justified in waging a 'hard war'. The following day he received Perron's surrender. Perron was now out of favour with Scindhia, and wanted to leave India with as much of his fortune as possible. By interrogating him Lake obtained much valuable information about the Mahratta forces and Hindustan's topology.

That same day Lake received information that a large Mahratta force commanded by one of Perron's subordinates, a certain Louis Bourquin, was 'preparing to dispute the passage of the Jumna with us.' Pester had grave concerns:

'The river at this season is nowhere fordable, and it is reasonable to conclude that much blood will be spilt on the banks of the Jumna before we cross it.'

Lake left the 1st Battalion, 4th Native Infantry in Allighur and began the 80-mile march northwest towards Delhi and Bourquin's army on the River Jumna. After 50 miles he encountered the fort at Khurja, taking it without a shot being fired, for the garrison fled in terror before 'the army that took Allighur'. Lake's force marched west on 10 September through marshy land with high, obscuring 'elephant' grass. This grass was to play a major role in the forthcoming battle.

Bourquin crossed the Jumna at Patparganj on 9 September, setting up an entrenched position south of the river. His army comprised 14 battalions of Mahratta regular infantry, led by French officers, with over 100 cannon in support. 5,000 Hindustani horse protected his right flank, while an equal number of Sikh mercenary cavalry guarded his left. Lake approached at 9 a.m. on 11 September. He now had just 4,500 fighting men: 3 cavalry regiments, 7 sepoy battalions, the 76th Foot, and 8 guns. His army had marched 18 miles since 3 a.m., and was suffering from chronic heatstroke and dehydration. Lake had actually ordered his men to bivouac and rest after their march; due to the long grass he had no idea of the Mahratta army's presence just two miles away. The 76th Foot had cooked their breakfast and were bathing in a nearby stream when Bourquin pounced.

'In history there is not a single instance recorded of so formidable a force, aided by even a more formidable train of artillery, being so completely annihilated by a handful of men.'

- Lieutenant John Pester's diary entry on the day of the Battle of Delhi

Just after 10 a.m., Lake's picquets came under fire from Mahratta horsemen. Hoping to deter the Mahrattas with a show of force, Lake advanced at the head of his cavalry (the 27th Dragoons, 2nd & 3rd Native Cavalry). He was in fact being led into a trap. The Mahratta horsemen withdrew as Lake pursued them, when suddenly 100 Mahratta cannon, hidden in long grass, erupted in a hideous salvo. Lake's men fell around him, but spurning retreat he led them forward in a heroic charge, which though costly may have saved the British army.

Lake's charge gave the British infantry time to reorganise and form up. With the remnants of his cavalry, he broke away from the Mahrattas and slowly withdrew. Bourquin took the bait: a great cheer went up from the Mahratta infantry as they set off in pursuit, leaving their strong defensive positions. Their cheers were cut short when they saw the cavalry peel off to reveal the British infantry advancing in perfect order, bayonets fixed.

Pester advanced at the head of the 2nd Native Infantry, on the left wing. He writes that despite a furious Mahratta cannonade, the troops… 'advanced most gallantly, without taking their muskets from their shoulders'. His horse fell victim to the first Mahratta volley. Seeing the sepoys beginning to waver, he mounted a stray and rode in front of the line shouting encouragement. General St. John, commanding the infantry, did not see him when he gave the order "Fire". Pester writes that he 'miraculously' escaped unhurt.

After this volley the British infantry drove back the Mahrattas and captured their guns. Bourquin's Sikh and Hindustani cavalry played no part in the battle and withdrew in panic. The infantry chased the Mahrattas to the Jumna crossing, inflicting terrible slaughter, while the cavalry kept up the pursuit until reaching Delhi. Mahratta losses exceeded 4,000.

Bourquin and the French officers surrendered on 15 September. The following day Lake crossed the Jumna and entered Delhi. There the Emperor, Shah Alam II, placed himself under British protection. Within a fortnight of crossing the Mahratta border, Lake had eliminated French power in northern India.

Capture of Deig

Lake went on to capture Agra on 17 October. For his bravery and example at the battle of Delhi, Pester was promoted to Brigade Major of 4th Brigade nine days later.

Another Mahratta ruler, Holkar of Indoor, made incursions into British-held territory in the summer of 1804. Holkar had rejoiced at seeing his old rival Scindhia so humiliated by the British, and lent him no assistance. Now he feared losing his estates. Holkar unsuccessfully besieged Delhi on 7-15 September, and the following month Lake went on the offensive. Despite reinforcements from the Raja of Bhurtpoor, Holkar's army of 15,000 was routed by Colonel Monson and Major-General J. H. Fraser at the battle of Deig on 13 November. Lake, leading the cavalry, joined forces with Monson and Fraser on 28 November. Colonel Don, marching from Agra with supplies and a large siege train, joined Lake on 1 December. Ten days later the siege of Deig began.

Deig was a formidable fortress, surrounded by five miles of thick mud walls and encircled by marshes. The only part of the fortress which could be attacked over solid ground was its strongest part, the Shah Burj, an intricate bastion mounted with a 70-pounder gun. Lake ordered a column of five regiments to attack the Shah Burj, spearheaded by the 76th Foot and the 1st European Regiment. Pester and the 2nd Native Infantry were also in this column, advancing silently during the night of 21 December. He recounts:

'Between our batteries and the breach the ground was very much broken. The troops were silent as death on our approach, but we were no sooner discovered from the works than the whole face was completely illuminated by the enemy's cannon and musketry. The shot flew like hail, and many a gallant fellow dropped; it was, however, no check to us, and instead of returning a single shot we rushed on, with the bayonet, and gained the summit of the breach.'

Pester records that the Shah Burj was taken after 20 minutes of bitter fighting. The enemy withdrew to the inner fortress and continued to defy the British until Christmas Day, whereupon Lake's army stormed into Holkar's palace. Pester had been assigned by Lake to the Prize Committee, and was responsible for finding Holkar's most valuable possessions. He located three lacs of rupees in a vault under the palace, and sent all treasure to the Artillery Park with an armed guard.

At the end of hostilities, Pester returned to Bareilly and resumed his tiger shooting. In April 1806 he returned to England on board H.M.S. Cumberland, stopping at St. Helena. He married Eliza Phelips in 1811, but had no children. He later returned to India, and was put in charge of the Intelligence Department during the Third Mahratta War. He retired in 1826 with the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel, his service record stating that he was never missing for a day except when on sick leave. He died at Millbrook, near Southampton, in 1856.

Pester's diary was published by his great-nephew in London in 1913, under the title War and Sport in India 1802-1806. It is the accepted history of the Second Mahratta War.

Reference sources:

Carter, T., Medals of the British Army in India (London, 1861).

Cooper, R. G. S., The Anglo-Maratha Campaigns and the Contest for India (Cambridge, 2003).

Pearse, H., Lake's Campaigns in India: The Second Anglo-Maratha War, 1803-1807 (London, 2007).

Pester, J., To Fight the Mahrattas: The Journal of an Officer of the 2nd Bengal Native Infantry 1802-1806 (London, 2009).

Puddester, R. P., Medals of British India, with Rarity and Valuations, Vol. 2, Part III. (Port Coquitlam, 2014).

Reid, S., Armies of the East India Company (Oxford, 2009).

Young, J., Galloping Guns (London, 2008).

Subject to 20% VAT on Buyer’s Premium. For more information please view Terms and Conditions for Buyers.

Sold for

£20,000

Starting price

£12000