Auction: 23001 - Orders, Decorations and Medals

Lot: 145

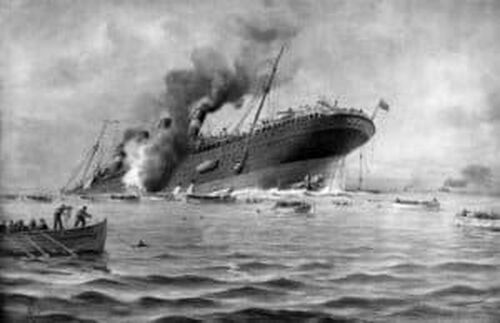

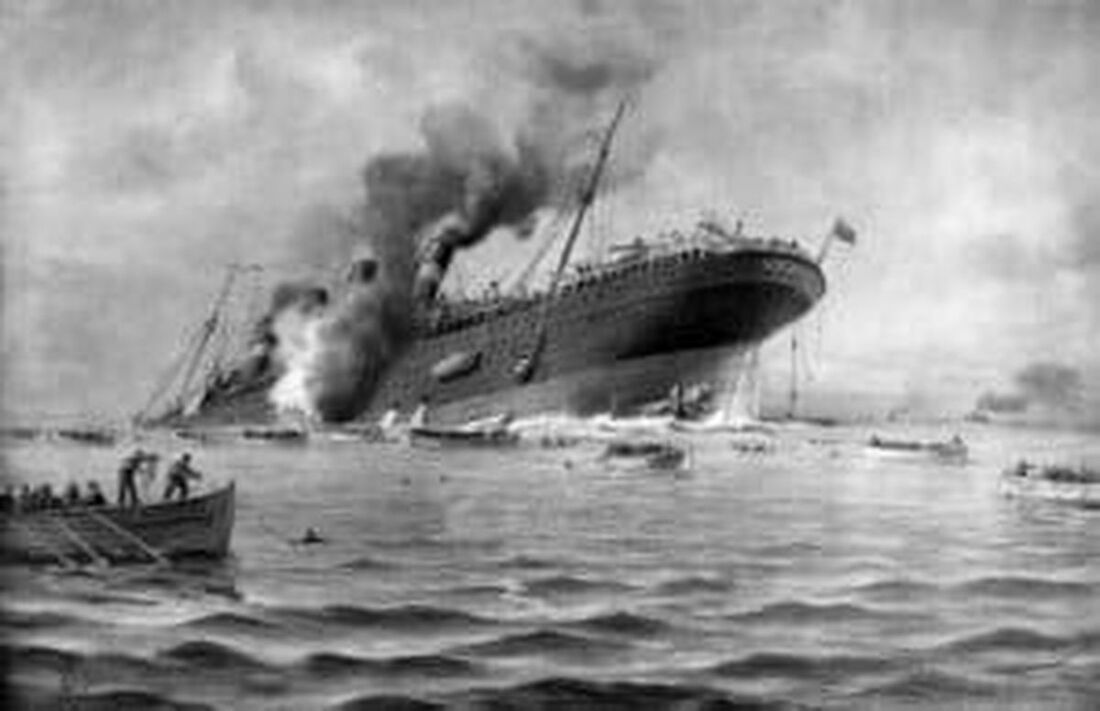

'On 7th May 1915, the steamship Lusitania, of Liverpool, was torpedoed off the Old Head of Kinsale and foundered. Morton was the first to observe the approach of the torpedoes and he reported them to the bridge. When the torpedoes struck the ship he was knocked off his feet but he recovered himself quickly, and at once assisted in filling and lowering several boats. Having done all he could on board, he jumped overboard.

While in the water he managed to get hold of a floating collapsible lifeboat and with the assistance of Parry, he ripped the canvas cover off it and succeeded in drawing into it 50 or 60 passengers. Morton and Parry then rowed the boat some miles to a fishing smack. Having put the rescued passengers on board the smack they returned to the scene of the wreck and succeeded in rescuing 20 to 30 more people.'

(So states the citation for the Sea Gallantry Medals awarded to both men.)

A notable Great War pair awarded to Leslie 'Gertie' Morton, Mercantile Marine, afterwards Royal Naval Reserve, a key eyewitness to the Lusitania disaster

At the subsequent court of inquiry, where his evidence was deemed crucial, Lord Mersey commended the 18-year-old seaman for his great courage and he was duly awarded the Sea Gallantry Medal in silver

It's a remarkable story, recounted by Morton in his autobiography, The Long Wake

British War Medal 1914-20 (Leslie Morton); Mercantile Marine War Medal 1914-18 (Leslie Morton), good very fine (2)

The only man with the surname 'Morton' and a Christian name 'Leslie' on the entire Mercantile Marine War Medal roll is 'Leslie Noel Morton'; TNA / Board of Trade records, refer.

He also appears on the TNA's roll of Great War naval awards as having received the British War and Victory Medals as a Sub. Lieutenant in the Royal Naval Reserve; these awards were sent to him by the Admiralty in September 1925.

His silver Sea Gallantry Medal is on display at the Merseyside Maritime Museum, Liverpool.

Leslie Noel Morton was born in Birkenhead, Cheshire in 1896. In common with his elder brother Cliff, he developed a great love for ships and the sea and, in 1910, aged 13 years, he signed up as an Ordinary Seaman on the sailing ship Beeswing at Liverpool, owned by J. B. Walmsley Ltd. It was aboard this vessel that he acquired his nickname 'Gertie', on account of his then high, unbroken voice.

Over the next four years he circumnavigated the world three times and rounded Cape Horn on six occasions. Having then returned to England in December 1914, his elder brother Cliff asked him to join him in another Walmsley-owned square-rigger, the Naiad, due to depart for New York, and thence Australia, in March 1915. With the promise of advancement to acting Second Mate, and with his own apprenticeship having expired, he agreed, but in the event both brothers regretted signing-up for Naiad. So much so, that on reaching New York they appealed to their father to send them funds for return passage to England. He duly obliged, sending them £37-10s-0d, thereby setting them on course the most momentous events of their young lives, for they purchased tickets for a cabin aboard the Lusitania.

As recounted in Morton's autobiography, The Long Wake, one of the Lusitania's officers persuaded them to sign on as deckhands, instead of travelling as passengers. Duly signed up as Able Seaman in the liner's deck department - for the princely sum of £5-10s-0d a month - they spent some of their father's funds on a final fling in Manhattan, Leslie passing out on Broadway after too many cocktails. He nonetheless reported promptly to Chief Officer Piper aboard the Lusitania the following morning, the eve of the great liner's departure.

The rest, as they say, is history, and in the case of Leslie Morton and his brother a remarkable chapter in maritime history.

One of Leslie's roles was to act as lookout. He takes up the story in his autobiography as Lusitania's fate unfurled on the 7 May 1915, as she neared her destination at Liverpool:'I was keeping a keen eye on my job as extra lookout, watching the water (and seeing a dozen things every few minutes) until, exactly at ten past two, I was looking out about four points on the starboard bow when I saw a turmoil, and what looked like a bubble on a large scale in the water, breaking surface some 800 to 1000 yards away. A few seconds later I saw two white streaks running along the top of the water like an invisible hand with a piece of chalk on a blackboard. They were heading straight across to intercept the course of Lusitania. I grabbed the megaphone which was provided for the lookout's use and, having drawn Jo Elliott's attention to them, reported to the bridge: "Torpedoes coming on the starboard side, Sir."

This was acknowledged from the bridge and, before I had time to think of anything else, there was a tremendous explosion followed instantly by a second one and a huge column of water and debris and steam went shooting into the air on the starboard side between No. 2 and 3 funnels of the ship. I immediately dived down the scuttle to the fo'c'sle to see if my brother, who was in the other watch, was moving and met him coming up the scuttle in his shirt and nothing more, very annoyed at the interference with his watch below. He asked me: "What the hell are you doing with the ship, Gertie?"

If I had had time to think I should have been very flattered indeed at this sudden promotion. I said, "We have been torpedoed we must get to our boat stations," and with that went back up the scuttle and along to my boat station on the starboard side of the boat deck at No. 11 Lifeboat.

At this juncture, having arrived at my boat station, I feel it necessary to say that in so far as my memory serves me I shall be describing the actual happening and events which I, personally, both saw and had a part in. This will, of course, provide a localised view-point of the ensuing thirteen minutes, by which time Lusitania was 300 feet down on the bottom of the sea.

Temptation very naturally exists for me to draw on the many able and competent books and articles which have been written on this disaster and also to call upon my memory of the subsequent very comprehensive official enquiry held at Caxton Hall later in the year, but this is a true picture, as I, a young man of eighteen years of age, actually saw and experienced it.

By the time I reached the boat Lusitania was already heeling fifteen to twenty degrees over to starboard, being drawn down on that side by the tremendous inrush of water into the great holes which had been torn in her hull by the explosion of the torpedoes, and she was going steadily over to starboard at that time without much indication that she was ever going to steady. At the same time she was going down by the bows so that we had the ship with a heavy and increasing list to starboard and a marked tilt down for'ard. The immediate effect of this list, which finally steadied at something approximating thirty degrees from the vertical, was to render the whole of the lifeboats on the port side of the boat deck completely useless, in so far as getting any people away from the vessel was concerned. They were, of course, all swinging into the ship's side and it was quite impossible to lower them on the type of derricks which at that time were in use.

This reduced the available boats to the starboard side, both lifeboats and the collapsible boats which were stored on deck under the lifeboats. Here again the problem of holding the boats into the ship's side to enable the passengers to embark in them required a considerable amount of skill, knowledge and seamanship, and it must be borne in mind when reading this description of the disaster, that we had lost over half the seamen in the explosion; they had been killed in the luggage and mail room which I had vacated some thirteen or fourteen minutes before the torpedoing. Whilst other members of the crew and, indeed, the passengers could be and in many cases were practical and useful, it is my opinion a job for seamen to get lifeboats out into the water and away with a maximum of security, efficiency and speed.

There was great excitement on the heavily listing boat deck with passengers, and crews of all departments rushing here and there, although the general excited comments, to my memory, seem to have been "surely she cannot sink. Not the Lusitania?" To me, a sailor, there was a strange feeling underfoot which one gets when a vessel is losing the buoyancy which will keep her afloat and which seems to be transmitted to the sailor's mind by the very feel of the deck under his feet. I have experienced a similar feeling in later years on a ship which was not truly stable and had a tendency to fall all over the place due to lack of stability. On this occasion even before we left port I remember feeling somehow under my feet that all was not right with this ship. I learnt later, from a few of the seamen that survived, that they also knew after the first few minutes that Lusitania had the feel of a ship which was doomed and could not recover her buoyancy.

I was at my boat's station by the after-lifeboat fall, that is the tackle with which one hoists and lowers boats, and we had her strapped in to the ship's side, at least partially, to prevent her swinging too far away with the heavy list and were getting passengers into the boat. Some of the more able-bodied were jumping the seven or eight feet into the boat which was, of course lower than the boat deck level. Others, in one way or another we helped across the gap. I remember at the subsequent enquiry when I was giving evidence, the incident of this gap between the lifeboat and the deck was the subject of a question put to me, as to how the "brave" seamen got the passengers into the boat with a gap between the deck and lifeboat. My reply was that if you had to jump six or seven feet, or certainly drown, it is surprising what "a hell of a long way" even older people can jump!

The lifeboat was quickly filled with her complement and in the word of one of the petty officers, I do not remember who he was, the man on the for'ard falls and myself on the after falls received the order "lower away." Here again this is a specialist job, lowering a lifeboat with sixty people in it, into the water, from a heavily listing ship. We lowered her down almost to the water's level but, with Lusitania still moving ahead through the water in the great circle which she was by this time describing and still travelling at four to five knots through the water, this presented a problem. Finally, we lowered her into the water by letting the falls run for the last couple of feet. Immediately the boat dropped back on its painter (which was fast for'ard); that is the common practice in these circumstances. She fell back one boat's length, came up alongside the heavily listing Lusitania and was directly under No. 13 lifeboat which was still in the davits. This lifeboat had been filled and I was about to go down the ropes, as was my duty, to try and get No. 11 lifeboat away from the sinking ship. The falls or tackles on No. 13 lifeboat, for which instructions had been given to lower away, were both handled by inexperienced men from one section or another of the catering or stewards' department and, instead of being lowered away the ropes went with a rush and No. 13 lifeboat, full of people, dropped twenty-five or thirty feet fairly and squarely into No. 11 lifeboat which was also full of people.

Terrible as this incident was, the tragedy of the overall picture did not give one time to waste in either horror or sympathy and I was looking out (having no boat now to attend to) to see if I could get a glimpse of my brother. The turmoil of passengers and life belts, many people losing their hold on the deck and slipping down and over the side, and a gradual crescendo of noise building up as the hundreds and hundreds of people began to realise that, not only was she going down very fast but in all probability too fast for them all to get away, did create a horrible and bizarre orchestra of death in the background.

I suddenly saw my brother at the for'ard end of the boat deck at No. 1 lifeboat which they had lowered halfway down to the water, full of people, so I went along at the 'double' and joined him and, finding that he had no one at the stern end of the boat to assist him, I took over the after fall and together we managed to lower away and get No. 1 boat into the water, Lusitania by this time had slowed down to about one or two knots. We immediately went down the falls into the boat which was full of passengers with no crew members in it and time was running extremely short.

Having got into the boat my brother at the for'ard end tried to push off with the boat hook and get her away from the ship. I was trying to do the same thing at the after end of the boat, but many of the passengers were hanging on to bits of rope from the side of the ship and the rails, which were now level with the water, in some mistaken belief that they would be safer hanging on to the big ship rather than entrusting their lives in the small lifeboat. Despite all our efforts we could not get her away from the ship's side and, as Lusitania started to heel over a little more, just before starting to settle by the head for her final dive, a projection on the side of the boat deck, which was nearly level with the water, hooked on to the gunnel of the boat we were in and inexorably started to tip it inboard. The time for heroics was obviously past and my brother yelled at the top of his voice, "I'm going over the side, Gertie." I replied, "So am I," and we waved and both dived over the outboard side of the lifeboat …

As I hit the water, and it is strange what one thinks about in times of stress, I suddenly remembered that my brother had never been able to swim, whereas I was a very strong and useful swimmer, one of the few sporting exercises at which I excelled. Having hit the water in a shallow dive and come up, I looked around to see if I could see my brother, but seeing the turmoil of bodies, women and children, deckchairs, lifebelts, lifeboats, and every describable thing around me, coupled with no less than 35,000 tons of Lusitania breathing very heavily down my neck and altogether too close for my liking, I went into what I used to believe was a useful double trungeon stroke with a quick glance over my shoulder as one of Lusitania's outsize funnels appeared to have its eyes exclusively on me.

The last clear impression in my mind at that time was seeing a collapsible boat slip off the deck of Lusitania into the water all lashed up. Why I should have noticed that, I do not know, but I had cause to he thankful in the course of the next few hours that I had seen it. I also remember Captain Turner on the bridge as she dived. I was swimming as hard as I could away from what we always thought would be a tremendous vortex created when the ship went down, and whilst swimming I suddenly heard, with the water splashing around me and my head, and all the other things and people around, an increasing and growing "wail" and looking again over my shoulder, thinking I was far enough away from Lusitania, I turned on my back and watched her as she started to settle rapidly by the head. The stern rose in the air, the propellers became visible and the rudder, and she went into a slow, almost stately, dive by the head, at an angle of some forty-five or fifty degrees. As she went down bodies, wreckage, people alive and dead were wiped off the decks until the water reached the stern, where hundreds had scuttered along as hard as they could go, climbing up the deck like a mountain to get to the back end. When Lusitania was better than half submerged for her total length, she hit the bottom, jarred, turned slowly over on her starboard side and disappeared from view for ever.

In the meantime, whilst there were all sorts of pieces and bits of wreckage, I suddenly thought of the collapsible boat which I had seen slip off the deck and, turning vaguely in the direction of where Lusitania had slowly come before diving, with the greatest good fortune in the world, at about 800 yards, I found the collapsible boat; it was like an oasis in the desert of bodies and people and momentarily was quite alone and unattended. I managed to scramble aboard and, although not being very strong physically, I had the knack, which is a good substitute for strength, learnt probably in my long years of hauling ropes and walking round windlasses in windjammers, and managed to get the canvas cover off and the sides, which were also canvas, up into position by hauling at the thwarts, one at a time. Just as I was completing this, a hand came over the rail or gunnel which I grabbed. It turned out to be Fred Perry [sic: Joseph Parry], one of the seamen. He did not seem to be injured although he was very, very sick, probably from some blow. However, he joined me in the boat, and we proceeded to collect as many people from the water as was possible; many of them we had to go out and collect as they were in danger of sinking. Others managed to get to the boat side and we hauled them aboard …

… By the time our collapsible boat had got about eighty people in it which was really the limit it could carry, probably a little over, the problem crossed my mind what to do and looking around I saw in the distance the smoke of some craft approaching. There were also a couple of South Irish fishing boats which had come up by this time, and so, getting the oars out with the help of those able-bodied passengers, we pulled over. Before steering for the trawler which turned out to be the Indian Empire, I had been steering towards one of the Irish fishing drifters which were picking up people, but deciding that the steam trawler would certainly make the port of Queenstown before the drifters, I altered course and went off to intercept Indian Empire …

By half past three we got all the people out of our collapsible boat on to Indian Empire. Quite nearby was an upturned lifeboat with eighteen or twenty people sitting on the upturned bottom, so we took our collapsible boat over, with the help of two of the crew of Indian Empire and picked up these people, together with others who were still floating. We did not know if they were alive or not; it turned out in this case that they were. We took them to Indian Empire and then boarded her ourselves. In the meantime, she had been picking up survivors from the water, the lifeboats, improvised rafts, one or two collapsible boats, on both sides, and in no time had three or four hundred people aboard.

The Captain, supported by this time by the arrival of other rescue craft, turned the bows of Indian Empire for Queenstown. In the meantime, I was wondering what had happened to my brother, Jo Elliott, and all my shipmates from sailing days as, apart from joining my brother in No.1 boat, before Lusitania went down, I had not caught a glimpse of hair or hide of any of them. Two of them had been with me down in the luggage room and I was in no doubt what had happened to them …'

Happily, the brothers were re-united at Queenstown, and took a train to Dublin before embarking on a ferry for Holyhead, thence journeying on to Liverpool and the family home in Leeds.

It was at the subsequent Court of Inquiry held at Caxton Hall that details of Leslie's bravery emerged, leading to his award of the Sea Gallantry Medal in silver.

Subsequent career

He subsequently enrolled at nautical college to study for his Board of Trade Second Mate's Certificate and, duly qualified, served in the cargo steamer Tyrian in the Mediterranean and in the liners Corinthian and City of Florence.

He was still serving in the latter ship when she was torpedoed and sunk by the UC-17 200 miles off Ushant on 20 July 1917: after being in an open boat for four days, the captain and his crew were rescued by the destroyer H.M.S. Midge.

Later that year, Leslie was commissioned as a Sub. Lieutenant in the Royal Naval Reserve and he went on to witness active service in the armed merchant cruiser Ophir, including in the Far East.

Post-war, he returned to the merchant service and was mainly employed by the Blue Funnel Line out of Liverpool. He published his autobiography The Long Wake in 1968, by which time he was a well-known broadcaster on a radio and television, particularly in respect of the Lusitania. He died on 22 September 1968, aged 71.

Subject to 20% VAT on Buyer’s Premium. For more information please view Terms and Conditions for Buyers.

Sold for

£650

Starting price

£480