Auction: 23001 - Orders, Decorations and Medals

Lot: 76

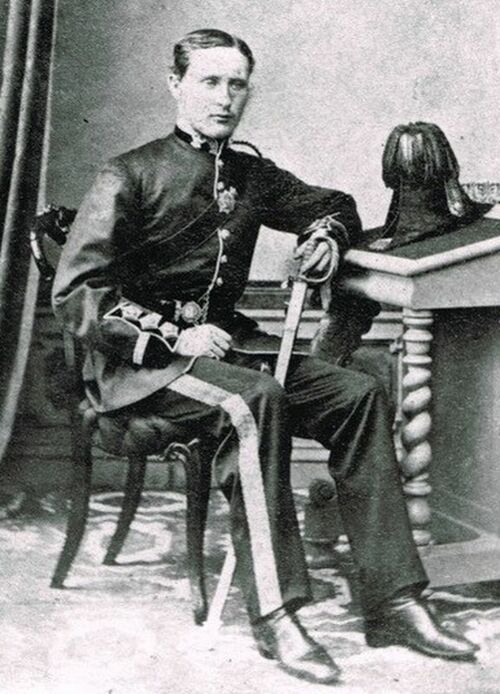

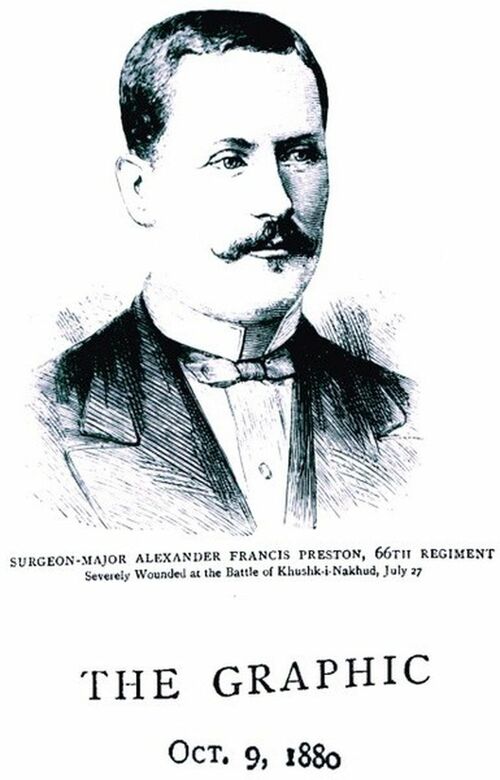

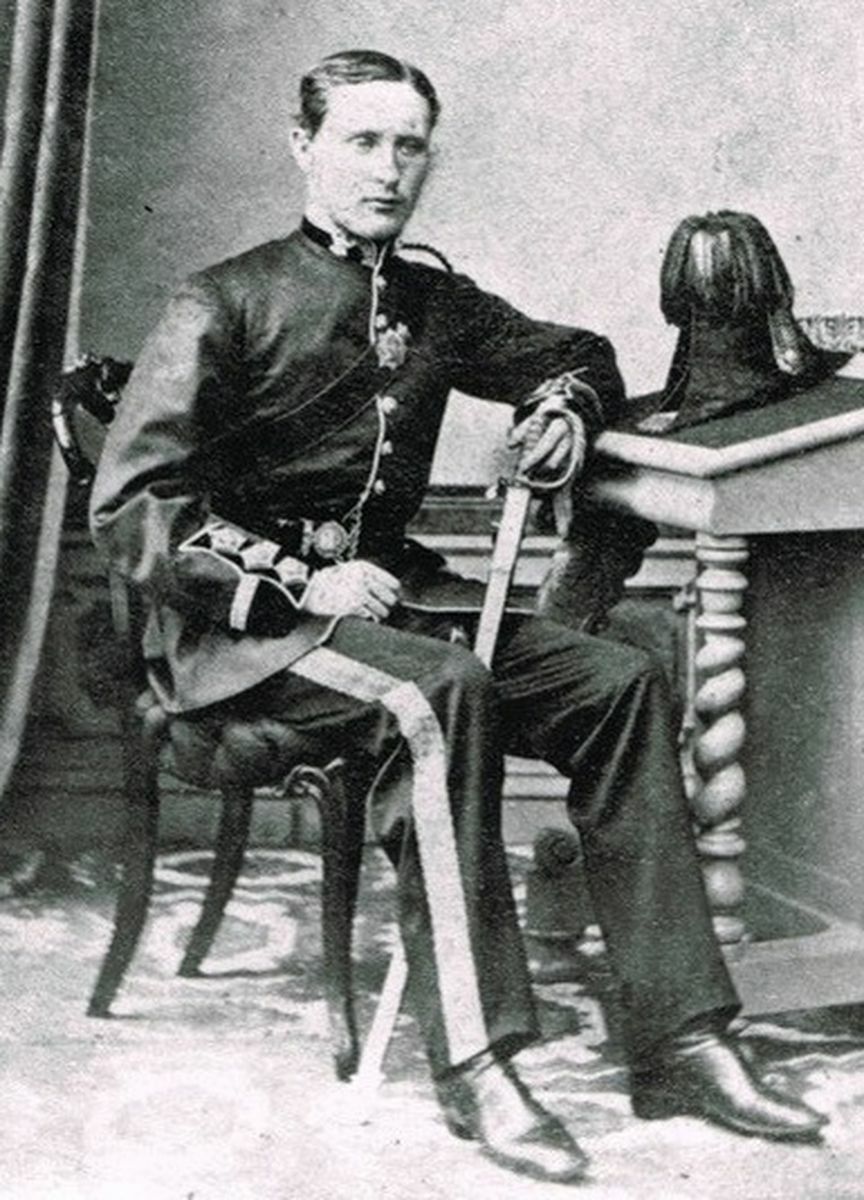

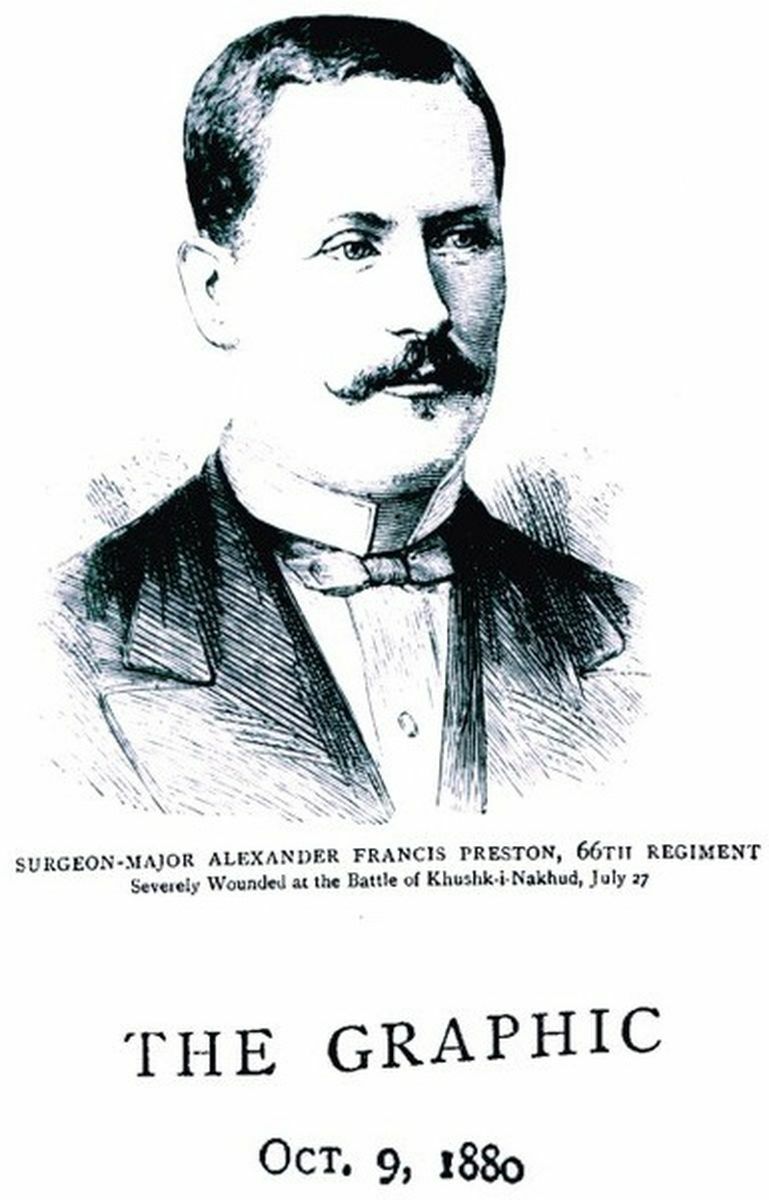

The astonishing 'Battle of Maiwand' group of three awarded to Surgeon-General A. F. Preston, Army Medical Department, twice severely wounded whilst serving with the 66th Foot in that famous action, and widely credited as the inspiration for Sherlock Holmes's companion Doctor Watson, whose fictional service in Afghanistan closely mirrors the real-life experiences of Preston

Convalescing in Portsmouth following his ordeal, Preston entered the circle of Arthur Conan Doyle, who worked for several years as a doctor at Netley during the period of Preston's recovery, and showed great interest in the Second Afghan War

Preston's later career is no less fascinating: he was Principal Medical Officer at Hong Kong during the Plague of 1894, and went on to become Honorary Physician to Queen Victoria and King Edward VII

Afghanistan 1878-80, no clasp (Surgn. Maj: A. F. Preston. A. M. Dept.); Jubilee 1897, silver issue, first with minor correction to second part of rank, good very fine (2)

M.I.D. London Gazette 19 November 1880.

Alexander Francis Preston was born at Killinkere in County Cavan, Ireland on 23 May 1842. His father, Decimus, was Rector of Killinkere, while his mother was the daughter of General Armstrong of the Royal Artillery. His grandfather was William Preston, Judge of Appeal, playwright, and early advocate of Catholic Emancipation.

Preston studied medicine at Trinity College, Dublin from 1861, and trained at the city's prestigious St. Steevens Hospital. At twenty one he became a Licentiate of the Royal College of Surgeons, Ireland. He embarked for Bengal on 20 May 1863, becoming an Assistant Surgeon in the Army Medical Department on 30 September. Preston also passed a course in Military Law. He was assigned to the 27th (Inniskilling) Regiment of Foot on 13 February 1866, and then to the Royal Artillery on 20 July 1867.

On 14 September 1867 Preston married Elizabeth, of the prominent Armenian Agabeg family, at St. Stephen's Church, Dum Dum, Calcutta. Their daughter Emily was born at Sialkote, Bengal on 14 January 1871, and Preston fathered two sons, Eyre Evans and William John Phaelin, in the subsequent two years. He advanced to the rank of Surgeon on 1 March 1873, but returned home on furlough on 22 April 1874. His youngest child, Frances, was born at Curragh in Ireland in 1875.

Promoted to Surgeon-Major on 28 April 1876, Preston embarked for Bombay on 12 January 1878, and thence to Afghanistan, attached to the 66th (Berkshire) Regiment of Foot.

Maiwand

The casus belli of the Second Afghan War was the refusal of Sher Ali Khan, Emir of Afghanistan, to accept a British diplomatic mission in Kabul. Lord Lytton, Viceroy of India, was concerned by the presence of Russian diplomats in the Afghan capital, and saw a direct threat to British influence. Some 50,000 British and Indian troops invaded Afghanistan in November 1878, quickly capturing the main cities. Sher Ali Khan appealed to Tsar Alexander II for assistance, but died in February 1879, and was succeeded by his son Yaqub, who quickly signed a peace treaty. Large parts of the country were ceded to Britain, the British diplomat Sir Louis Cavagnari was admitted to Kabul, and for a time all seemed quiet. On 3 September 1879, however, Afghan resentment boiled to the surface: Cavagnari and his staff were massacred.

Major-General Sir Frederick Roberts recaptured Kabul that winter, but the uprisings only grew. Kandahar, 300 miles south of the capital and widely regarded as safe, was held by a 4,000-strong garrison under Lieutenant-General Primrose, of which the 66th Foot was the main British element. Further west, at Herat, Afghan resistance was being led by Ayub Khan, the charismatic 'other' son of Sher Ali. When Ayub marched a large host towards Kandahar in June 1880, Primrose sent Brigadier-General Burrows with 2,500 men, including six companies of the 66th Foot, to intercept this Afghan army before it crossed the River Helmand.

At Ghirisk, a strategic crossing, Burrows was expected to rendezvous with Afghan levies led by the recently installed Wali of Kandahar. In the event, the levies deserted Burrows and flocked to Ayub Khan's banner, swelling the Afghan army to more than ten times the size of Burrows's force. On 15 July General Stewart, Commander-in-Chief in India, telegraphed to Primrose: 'Wali's troops having deserted, the situation has completely changed. General Burrows must act according to his own judgment, reporting fully. He must act with caution on account of distance of support.'

After a tense skirmish on 14 July at which Preston was present, Burrows reluctantly abandoned Ghirisk and moved east across the Helmand desert towards Kandahar, the only place from which support might come. Ayub Khan had amassed a rare coalition of Helmandi tribes, including Alizai, Noorzai and Barakzai warriors armed with vicious charay knives. Though fanatical ghazis were its spearhead, Ayub Khan's army included regular battalions drilled in European tactics, and he could field five batteries of artillery, some of them with breech-loading Armstrong guns. Burrows could only guess at the numbers encircling him, but Elphinstone's ghost stood at his elbow, and memories of 1842 plagued every British heart.

The song British Grenadiers celebrates men 'who know no doubts or fears'. This accurately describes the 66th Foot, whose defiant stands against overwhelming odds did much to slow the Afghan pursuit. Four smoothbore guns were actually captured during the retreat, and the 66th detached an officer and 42 men to serve as their crews. These guns supplemented those of E Battery, Royal Horse Artillery, whose exploits in the coming battle are well documented. On 21 July, Burrows halted the retreat at Khushki-i-Nakhud, 45 miles from Kandahar. Five days later a political officer warned of an Afghan presence in the Maiwand valley, eight miles away, which Burrows took to be an advance guard. At dawn on 27 July, Burrows duly ordered his men into that arid, open plain, only realising when it was too late that Ayub Khan's entire army was arrayed against him.

Battle was joined at 11.45 a.m. with an artillery duel between E Battery and the Afghan Armstrongs. Men of the 66th Foot operated the four captured smoothbores in the centre of the British line, firing case-shot at any ghazis who approached. In his despatch, printed in the London Gazette on 19 November, Burrows stated that his position held firm 'for nearly three hours', until two native regiments guarding his left flank, Jacob's Rifles and the 1st Grenadiers, 'rolled up like a wave to the right'. This left the 66th facing 'complete annihilation'. Colonel Galbraith was killed while grasping the Queen's Colour, which fell into enemy hands, and the London Gazette confirms that Surgeon-Major Preston was wounded while tending to casualties. HIs obituary, published in 1907, adds further detail:

'Preston sustained two severe wounds during the battle, including a bullet wound to his back.'

Reduced to 150 effectives, the 66th had to cross a 25-foot ravine before reaching a walled garden in the village of Khig. They continued firing until the last round was spent. Afghan sources noted in awe how the last eleven men, comprising two officers and nine privates, charged into the mass of ghazis, determined - to paraphrase Kipling - to go to their God like soldiers. Maiwand was not a victory, and no 'Maiwand' clasp was awarded, but Primrose considered that: 'History does not afford any grander or finer instance of gallantry and devotion to Queen and Country.' This heroic stand allowed Burrows to extract the rest of his force. Captain Slade, commanding E Battery, put Preston on a gun carriage with the other wounded. After 33 hours of relentless pursuit by hostile tribesmen, the exhausted survivors reached Kandahar.

In all, ten officers of the 66th Foot were killed at Maiwand, and only two were wounded, of which Preston was the sole Surgeon. After the battle, Ayub Khan subjected Kandahar to a month-long siege, during which Preston was again wounded. As Medical Officer in Charge, Preston tended to the soldiers' wounds throughout this ordeal. General Roberts led a relief column from Kabul, covering the 300 miles in 30 days, and on 1 September defeated Ayub Khan's army at the Battle of Kandahar. Having installed the sympathetic Adbur Rahman Khan as Emir at Kabul, British forces left Afghanistan.

Preston's service record states that Major-General W. H. Seymour brought Preston's service in the Second Afghan War to the attention of the Duke of Cambridge, then Commander-in-Chief of the Forces. Invalided to England on 10 November 1880, Preston received a year's pension for wounds, and was permitted to visit the south of France with his family.

Hong Kong to Osborne House

His strength recovered, Preston returned to India in September 1884 and was promoted to Brigade Surgeon, with the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel (London Gazette, 4 January 1887). Preston left India for good on 27 January 1890, and the 1891 census shows him living with his wife Lizzie at 4 Brunswick Terrace, Portsea, Portsmouth.

Advanced to Surgeon Colonel on 28 May 1892, Preston sailed to Hong Kong with his daughter Frances on 6 January 1893. They lived at 1 Queen's Gardens, which today is a skyscraper filled with luxury apartments. Preston was Principal Medical Officer on the island during the outbreak of bubonic plague that killed thousands in 1894. Preston supervised the whitewashing of houses by the King's Shropshire Light Infantry, and oversaw the use of disinfectants. He applied the most up-to-date science and saved many lives, not just in Hong Kong but throughout south-east Asia, where the virus could easily have spread. Local resistance to Western medicine was gradually overcome. Preston is mentioned in a list of officers who rendered special service in Hong Kong, in recognition of which, he was promoted to Surgeon Major-General (London Gazette, 30 March 1896). He performed his duties despite personal tragedy: his daughter Frances fell victim to the disease, aged 19, on 27 November 1893 and is buried in the Happy Valley Cemetery, Hong Kong.

Preston left Hong Kong on 26 March 1896, arriving home in Portsmouth exactly one month later. Queen Victoria and King Edward VII both employed Preston as Honorary Physician. Preston was rewarded for his devotion to the Queen in her last days at Osborne, rising to the highest possible rank, Surgeon General, on 11 March 1901 (six weeks after the Queen's death). He received the 1897 Jubilee Medal. The 1907 Medical Directory lists Preston as: 'Hon. Phys. to H.M. the King'.

Briefly Director General of Army Medical Services, Preston's last military appointment was as Principal Medical Officer of the 3rd Army Corps, based in Ireland. Leaving the Army with a good service pension on 23 May 1902, he devoted his leisure to golf, travel, and sport, and was a stalwart of the Royal Irish Yacht Club. He was an active Freemason, joining the Khyber, Bombay, and Hong Kong Lodges at different stages of his Army career. Preston's obituary in the British Medical Journal said of him:

'His great abilities were hidden by his geniality.'

Preston died at 53 Redcliffe Gardens, West Brompton on 24 July 1907, aged 65. Buried at Kensal Green Cemetery, he left an estate of £6,158.0.5. His wife Lizzie survived him by 12 years, and died at the Hotel Bristol in Menton, near Nice. His son William John Phaelin commanded the 97th Deccan Infantry in Mesopotamia during the Great War; severely wounded, William was mentioned in despatches and awarded the DSO.

A Legacy in Literature

Arthur Conan Doyle had a medical background, graduating as a Doctor of Medicine from the University of Edinburgh in 1885. The 1891 Medical Register shows him living at 1 Bush House, Elm Grove, Portsmouth, a few hundred yards from the residence of Surgeon-Major Preston in Brunswick Terrace. At the time of Maiwand, Conan Doyle was working as a ship's surgeon aboard the whaler Hope of Peterhead, but from 1882 he ran a private practice in Portsmouth. In his memoir Memories and Adventures (1924), Conan Doyle described how, in 1882:

'A new wave of medical experience came to me about this time for I suddenly found myself a unit in the British Army. The operations in the East had drained the Medical Service and it had therefore been determined that local civilian doctors should be enrolled for temporary duty of some hours a day.'

Conan Doyle worked at The Royal Victoria Hospital, Netley in support of the Army doctors, and may even have treated Preston during his recovery. Already a prolific author of short stories, Conan Doyle became Joint Secretary of the Portsmouth Literary and Scientific Society. On 20 November 1883, one of Netley's most senior doctors, Surgeon-Major George Evatt, gave a talk to the Society entitled: 'The Army Doctor and his Work in War'. According to the Sherlock Holmes Society of London, this talk may have touched on Surgeon-Major Preston's exploits at Maiwand. Several ex-Indian Army officers retired to Portsmouth in the 1880s, and it is likely that Preston's tale was much discussed. Evatt knew Preston well, later succeeding him as Principal Medical Officer of Hong Kong. It is very probable that Preston's story inspired the young author. This conclusion is supported by a close reading of A Study in Scarlet, the first novel of the Sherlock Holmes series. Conan Doyle wrote it during 1886, three years after Evatt's talk, and its plot begins with Dr John Watson narrating his experiences of Afghanistan:

'The campaign brought honours and promotion to many, but for me it had nothing but misfortune and disaster. I was removed from my brigade and attached to the Berkshires, with whom I served at the fatal battle of Maiwand. There I was struck on the shoulder by a Jezail bullet, which shattered the bone and grazed the subclavian artery. I should have fallen into the hands of the murderous Ghazis had it not been for the devotion and courage shown by Murray, my orderly, who threw me across a packhorse, and succeeded in bringing me safely to the British lines. Worn with pain, and weak from the prolonged hardships which I had undergone, I was removed, with a great train of wounded sufferers, to the base hospital at Peshawur…I was despatched, accordingly, in the troop-ship Orontes, and landed a month later on Portsmouth jetty, with my health irretrievably ruined, but with permission from a paternal government to spend the next nine months in attempting to improve it.'

The similarities with Preston's real-life tale are hard to ignore. Patrick Mercer, whose 2011 book Red Runs The Helmand expands on Dr Watson's service, believes there can be no doubt that Conan Doyle based the character of Dr Watson on Preston. This being the case, Preston can be credited with inadvertently creating the most famous duo in crime fiction. In the next scene of A Study in Scarlet, Watson is astonished when, on being introduced to Holmes, the detective says to him:

'You have been in Afghanistan, I perceive.'

When asked how he knows this, Holmes replies:

'The train of reasoning ran: "Here is a gentleman of a medical type, but with the air of a military man. Clearly an army doctor then. He has just come from the tropics, for his face is dark, and that is not the natural tint of his skin, for his wrists are fair. He has undergone hardships and sickness, as his haggard face says clearly. His left arm has been injured. He holds it in a stiff and unnatural manner. Where in the tropics could an English army doctor have seen much hardship and got his arm wounded? Clearly in Afghanistan." The whole train of thought did not occupy a second. I then remarked that you came from Afghanistan, and you were astonished.'

This memorable encounter between doctor and detective is the reader's first taste of Holmes's extraordinary deductive powers. It lays the foundation for all subsequent cases, and underpins the relationship between the two characters. It is a partnership built on mutual respect: Holmes admires Watson's physical endurance, while Watson is enthralled by Holmes's mental skill. Small wonder that in The Abominable Bride (2016), a special episode of the BBC series starring Benedict Cumberbatch and Martin Freeman set in Victorian London, Freeman (Watson) describes his ordeal, and the audience is transported to the Battle of Maiwand.

The new custodian of Preston's Medals will own a piece of literary as well as military history, for it is through Dr Watson that Preston's real-life story will inspire future generations.

Sold together with an impressive folder of research that includes London Gazette entries, service records, genealogical searches, and a copy of the recipient's Will.

Subject to 20% VAT on Buyer’s Premium. For more information please view Terms and Conditions for Buyers.

Sold for

£5,500

Starting price

£1800