Auction: 22075 - Orders, Decorations and Medals

Lot: 121

INTRODUCTION

Upon the foundation of the Special Operations Executive (S.O.E.) on 22 July 1940, their brief was simple - to recruit, supply and train an underground army capable of carrying out sabotage attacks on the enemy in Occupied Europe (and latterly South-East Asia). Its activities - and its operators - were just as fabled and gallant as the plethora of subsequent publications and screen dramatisations which have told their personal stories to a wider audience.

The fact that the Personnel Files (PF Series) of the S.O.E. were not released to the National Archives until as recently as 2003 tells you all you need to know. Furthermore, its own description states:

'The contents in any individual's file can vary considerably however…some papers on many of the files are damaged or mutilated to some extent: many have been partly burnt; some names have been removed by being cut out from papers at some time in the past. The files also include papers in many different languages, according to the work performed by the individual concerned. Some extracts continue to be retained by the Department under section 3(4) of the Public Records Act.'

Plenty of the interference in said files was probably undertaken by those who remained in Government employ but had served in the 'Baker Street Irregulars'. They sought to protect those who had given so much for the cause. Upon accessing the files of Francis Suttill (aka Francois Desprez) (TNA HS 9/1430/6, refers), his is quite clearly one file in which the 'editors' have been to work. Perhaps this is one reason why so many conspiracy theories and speculation has surrounded the fall of the PROSPER circuit over the years.

The facts of his actual operational service have never been called into question - period. Suttill, despite childhood polio which left him with one leg an inch shorter than the other, excelled and was a natural leader. He was personally chosen to command 'F' Section's most important circuit, by Colonel Maurice Buckmaster who noted that his sharp mind '…cut like a knife into the problems we put before him.'

Details of the extensive acts of sabotage, nerve-jangling radio transmissions and derring-do in which Suttill was involved are expertly detailed in his son's updated 2018 publication: Prosper - Major Suttill's French Resistance. Besides the former acts, the important work of securing, storing and distributing the canisters - one of which, with exact details of its contents, is to be offered with the Archive accompanying the Medals - which were dropped with essential supplies and arms by the 'Special Duties' Squadrons of the Royal Air Force, were a standout of the circuit.

Upon meeting with Francis's son, at his home in Herefordshire, it is fair to say I was greeted with such a warmth and passion in sharing my vision for bringing his late father's story to a wider audience. It is my hope that the following catalogue entry will inspire you to dig a little deeper into the remarkable stories of that gallant band of individuals. Of the women too, for the Second World War was not so restricted to men as the Great War had been. Suttill constantly and effectively worked shoulder-to-shoulder with the fairer sex and could count Noor Inayat Khan G.C. as part of the network. The pair had shared a joyful lunch at Grignon and Suttill had personally been present to receive the 'drop' which contained Khan's first transmitter and personal effects. Little more need be said about her exploits.

In Suttill's case, he quite literally gave his life and endured years of terror and torture at the hands of the enemy, latterly in solitary confinement in Cell 10 of the Zellenbau at Sachsenhausen Concentration Camp. His story certainly did not end with his execution and he never gave an inch before that sombre moment.

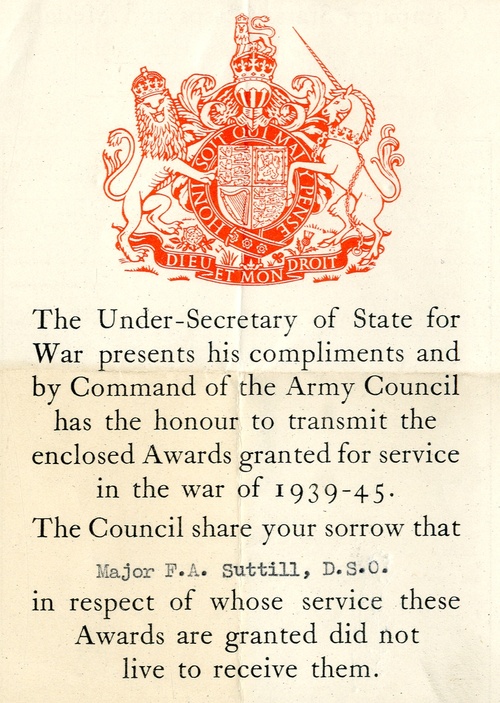

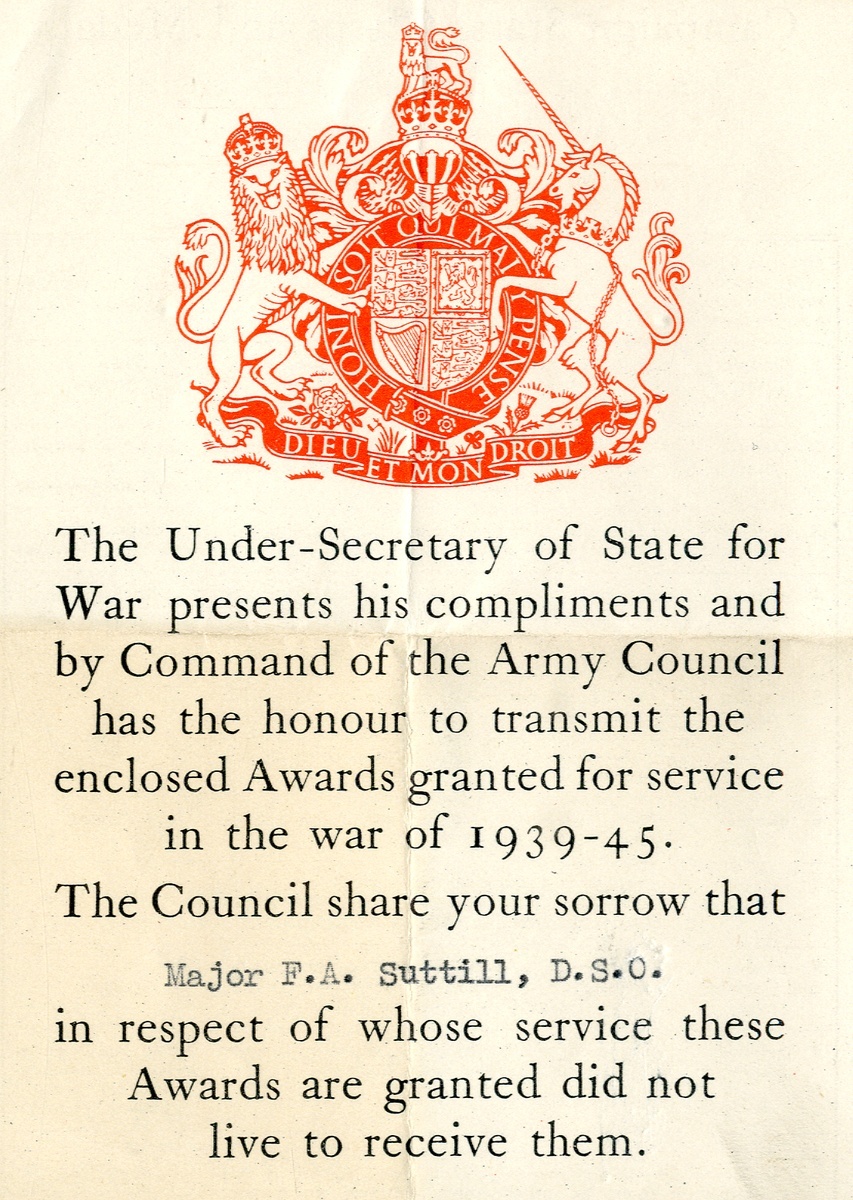

Despite the fact that authorities back home knew of his capture and the grave consequences that applied, Colonel Gubbins still put him in for his richly-deserved D.S.O. in the summer of 1945. Had his execution been confirmed to London then it could simply not have been awarded. It stands as a testament to his service, and perhaps he would have earned yet higher laurels if the full horrors of his final months were fully known.

Whilst this catalogue entry simply cannot do justice to a short life lived to the full in the space to which it is afforded, I have attempted to draw upon as many first-hand sources as possible. Given the nature of the work of the S.O.E., it is easy to stray into speculation. The intention of this entry is not to further fuel the debate around PROSPER (which has raged for decades) but to present a brief snapshot into the life and times of this true hero. Any such errors are mine and mine alone.

Despite drawing upon the plethora of Reference Sources cited below, nine simple words from the man himself summed it all up for me:

'My one wish is to be used in France.' He certainly did that.

Marcus Budgen, August 2022

Sold by Order of Francis J. Suttill

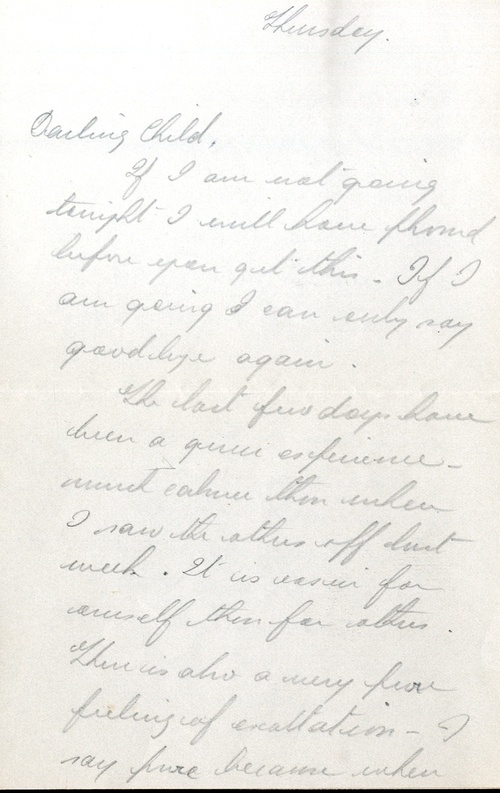

'The last few days have been a queer experience - much easier than when I saw the others off last week. It is easier for oneself than for others. There is also a very pure feeling of exultation - I say pure because when one is at last facing the real thing, which is nothing more or less than a protracted 'going over the top', there is no feeling of what you would rightly call 'showing off'.

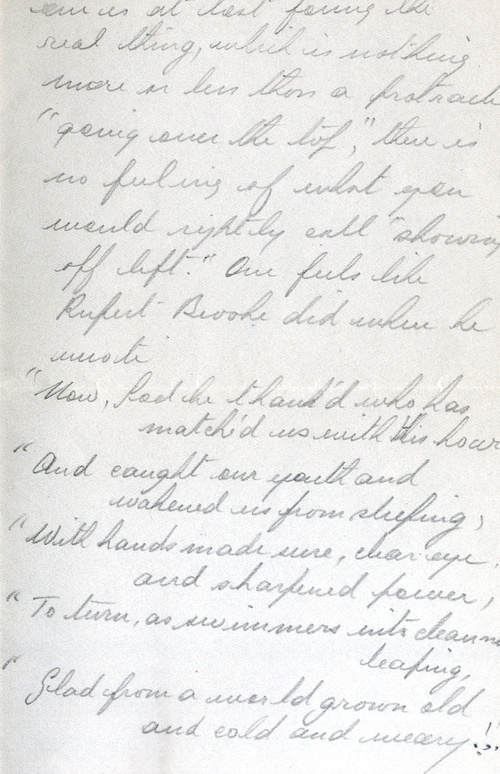

One feels like Rupert Brooke when he wrote -

"Now, God be thanked who has matched us with his hour, And caught our youth, and wakened us from sleeping, With hand made sure, clear eye, and sharpened power. To turn, as swimmer into cleanness leaping, Glad from a world grown old and cold and weary."

But that world does not include the portion you inhabit because that is in my heart and is with me.

Goodbye my love, Francis.'

The final letter written to his wife on 1 October 1942, before 'dropping' into France to establish PROSPER

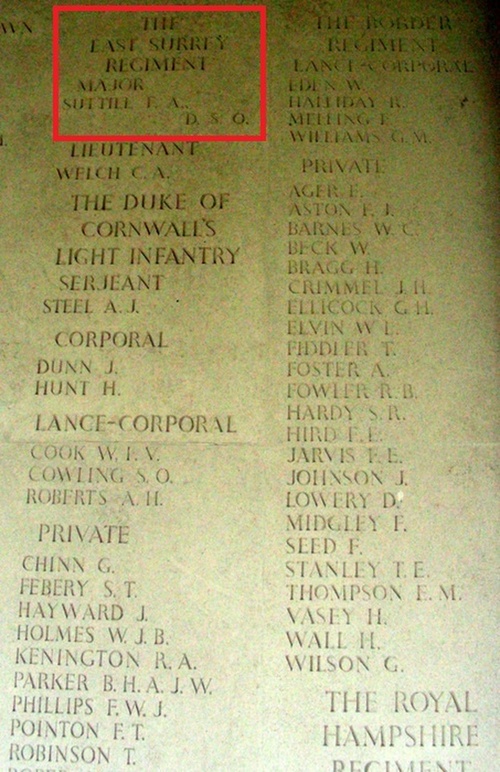

The Historically Important 1945 D.S.O. group of four awarded to Major F. A. Suttill, East Surrey Regiment and 'F' Section, Special Operations Executive (S.O.E.), Agent 'PROSPER', whose codename was shared by the network he established and ran in Paris and Northern France, it was to grow to be the largest - and the most important - network to operate in France during the Second World War; PROSPER quite literally answered Prime Minister Winston Churchill's directive to the S.O.E. to '...set Europe ablaze!'

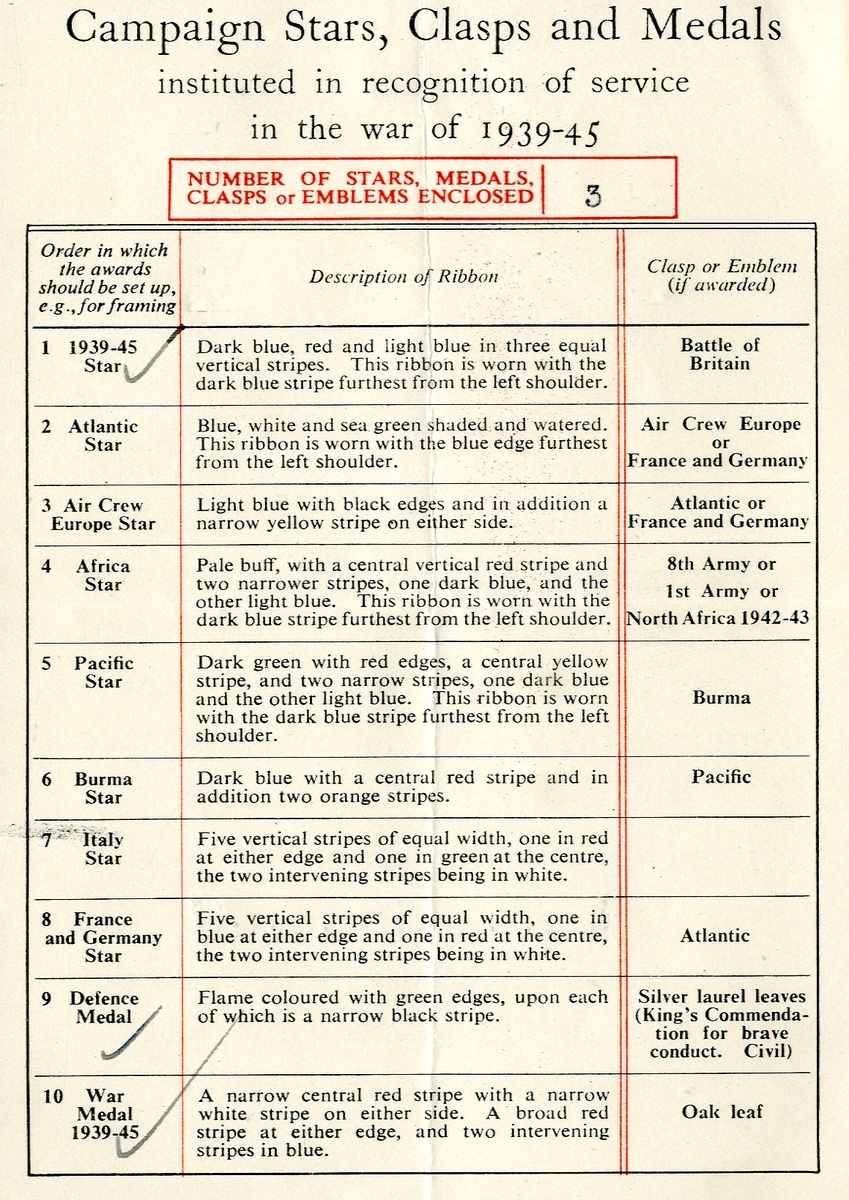

Distinguished Service Order, G.VI.R., the reverse officially dated '1945', in its Garrard & Co., case of issue; 1939-45 Star; Defence and War Medals 1939-45, nearly extremely fine (4)

D.S.O. London Gazette 15 November 1945. The original Recommendation, by the Head of the S.O.E. Major-General Gubbins, was submitted on 14 June 1945 and states:

'This Officer was parachuted into France on 1st October 1942 to organise resistance in the Paris area. In six months he built up one of the most powerful circuits in France in an area little suited to clandestine work. By his remarkable personality and diplomacy he established excellent relations with the various groups in and around Paris, and organised them on a secure and efficient basis. The ramifications of his organisation extended as far as Le Mans, Orleans and Beauvais, and sub-organisers were appointed to take charge of the outlying groups.

Major Suttill organised the reception of arms and explosives on a large scale, and achieved excellent results with the stores received. His most notable achievements were the sabotage of the Chaingy power station in March 1943 by which the power lines from Eguzon, Chevilly, Epines Fortes were immobilised; the destruction of 1,000 Litres of petrol and successful attacks on enemy goods trains on the Orleans-Paris line. During April 1943 his groups carried out 63 sabotage operations against the enemy, derailing three troops trains, killing 43 Germans and wounding 110. Whenever possible, Suttill personally led these operations against the enemy and inspired his men by his remarkable personal courage. The activities of his groups became so widespread that for several months the Gestapo concentrated all their efforts on breaking up the circuit. They finally arrested Suttill at the end of June 1943.

During his 9 months of clandestine work, this Officer made a very great contribution to the organisation of resistance in northern France. The achievements he attained were quite unparalleled at that period. A magnificent leader, he was an inspiration and an example to all who worked with him, both British and French. He showed outstanding bravery and self-sacrifice, and never failed to carry out personally the most dangerous tasks. It is strongly recommended that he be appointed a Companion in the Distinguished Service Order.'

Sold together with the comprehensive original archive of material to include:

(i)

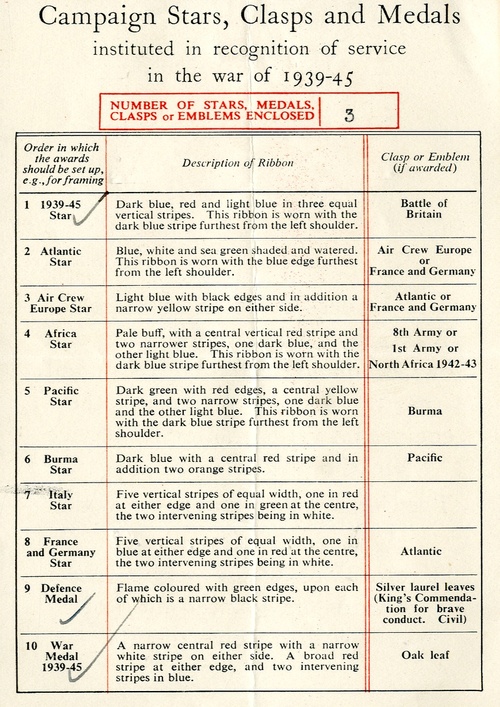

O.H.M.S. box of issue for the Campaign Medals, the lid ripped upon opening, named in ink to 'Mrs.....173 O...' and with the Condolence Slip denoting '3' awards in the name of 'Major F. A. Suttill, D.S.O.'

(ii)

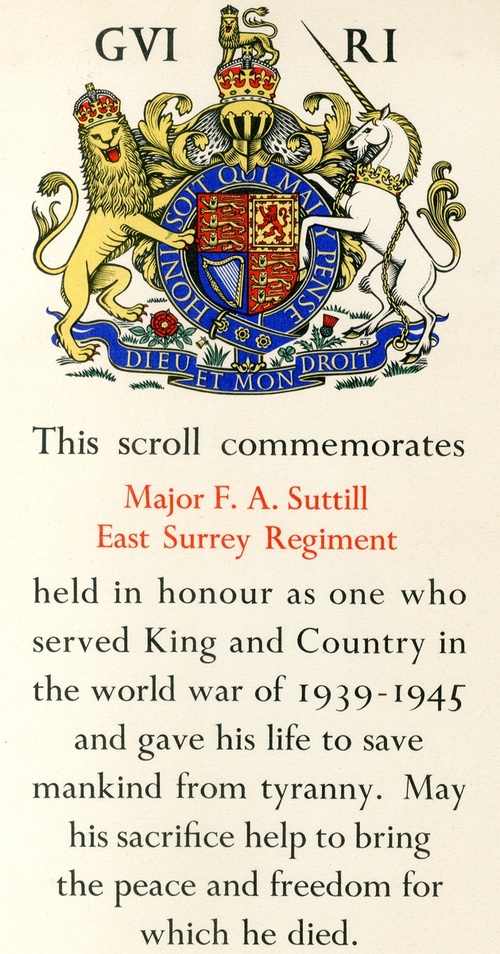

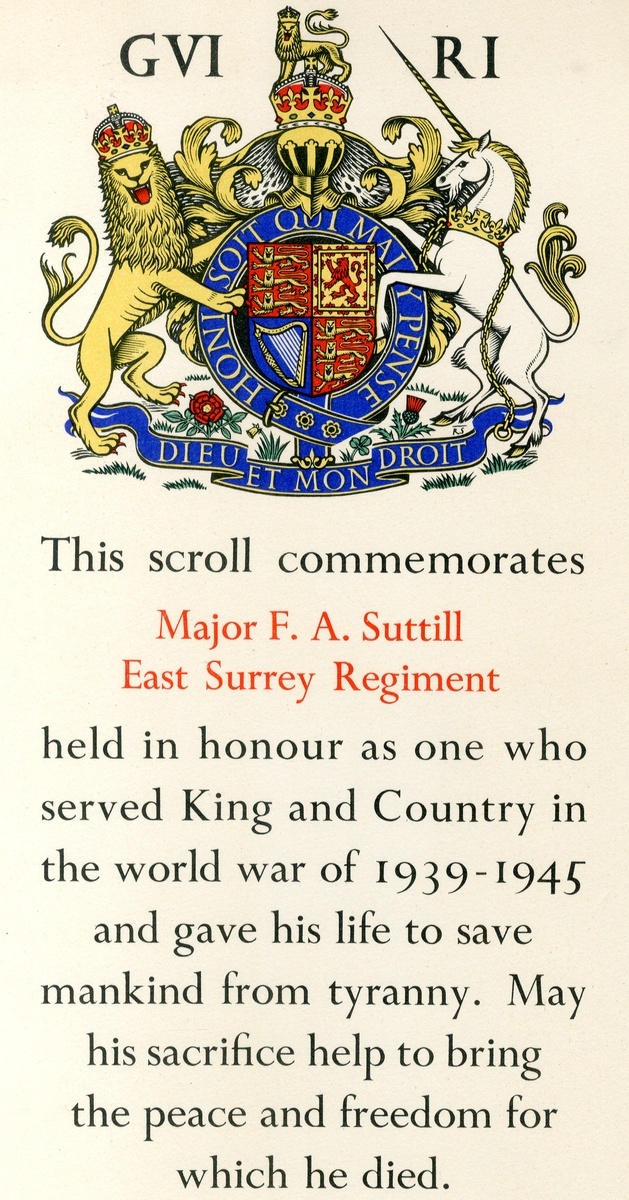

Buckingham Palace Memorial Scroll in the name of 'Major F. A. Suttill, East Surrey Regiment', in its O.H.M.S. envelope sent to 'Mrs M. J. Suttill, 50A Fulham Road, London, S.W.3.' on 9 November 1948, together with the Buckingham Palace enclosures.

(iii)

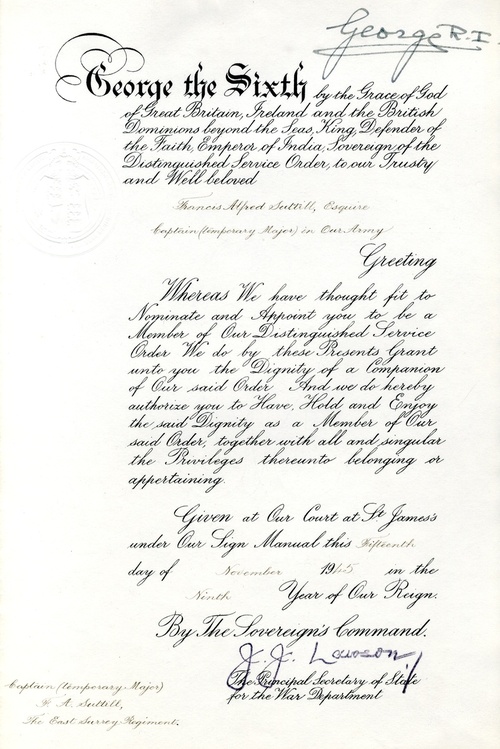

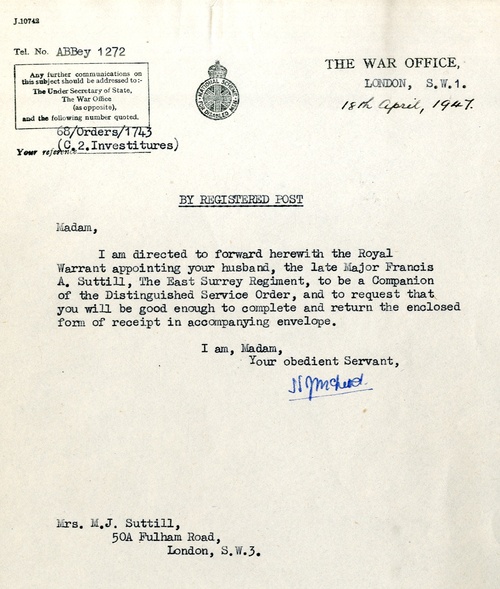

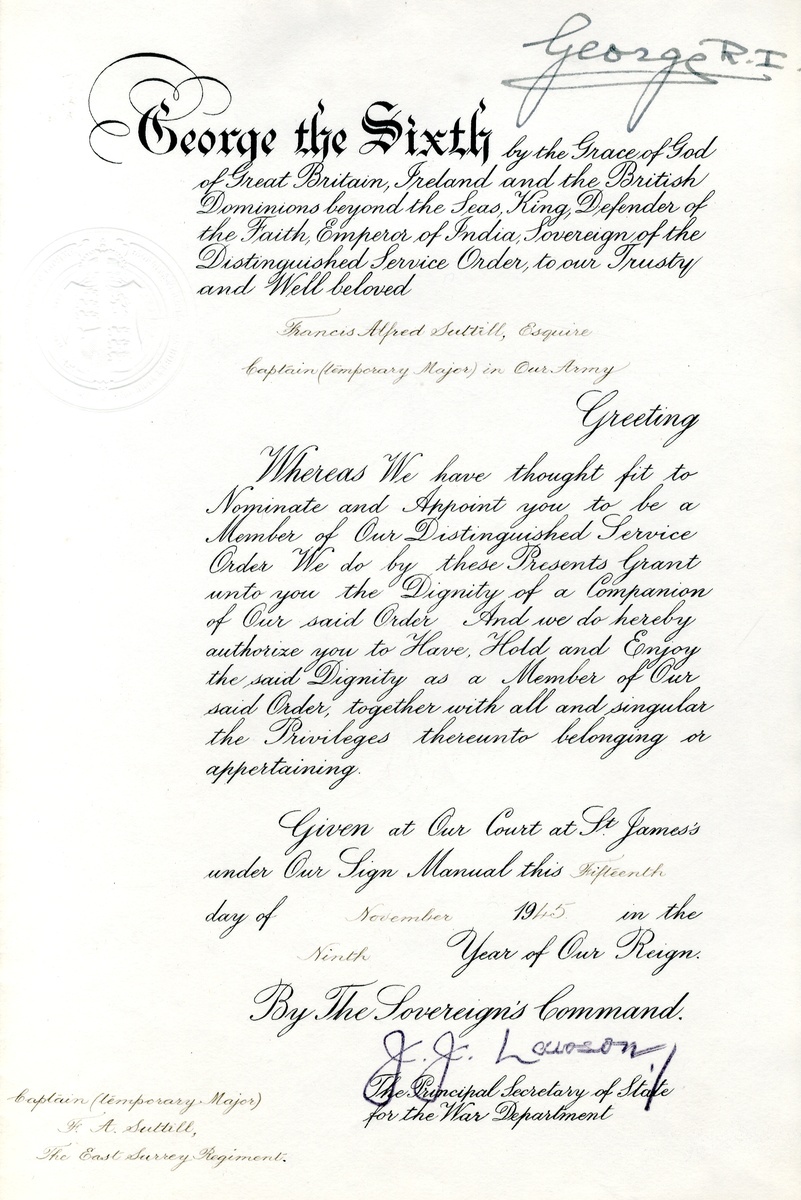

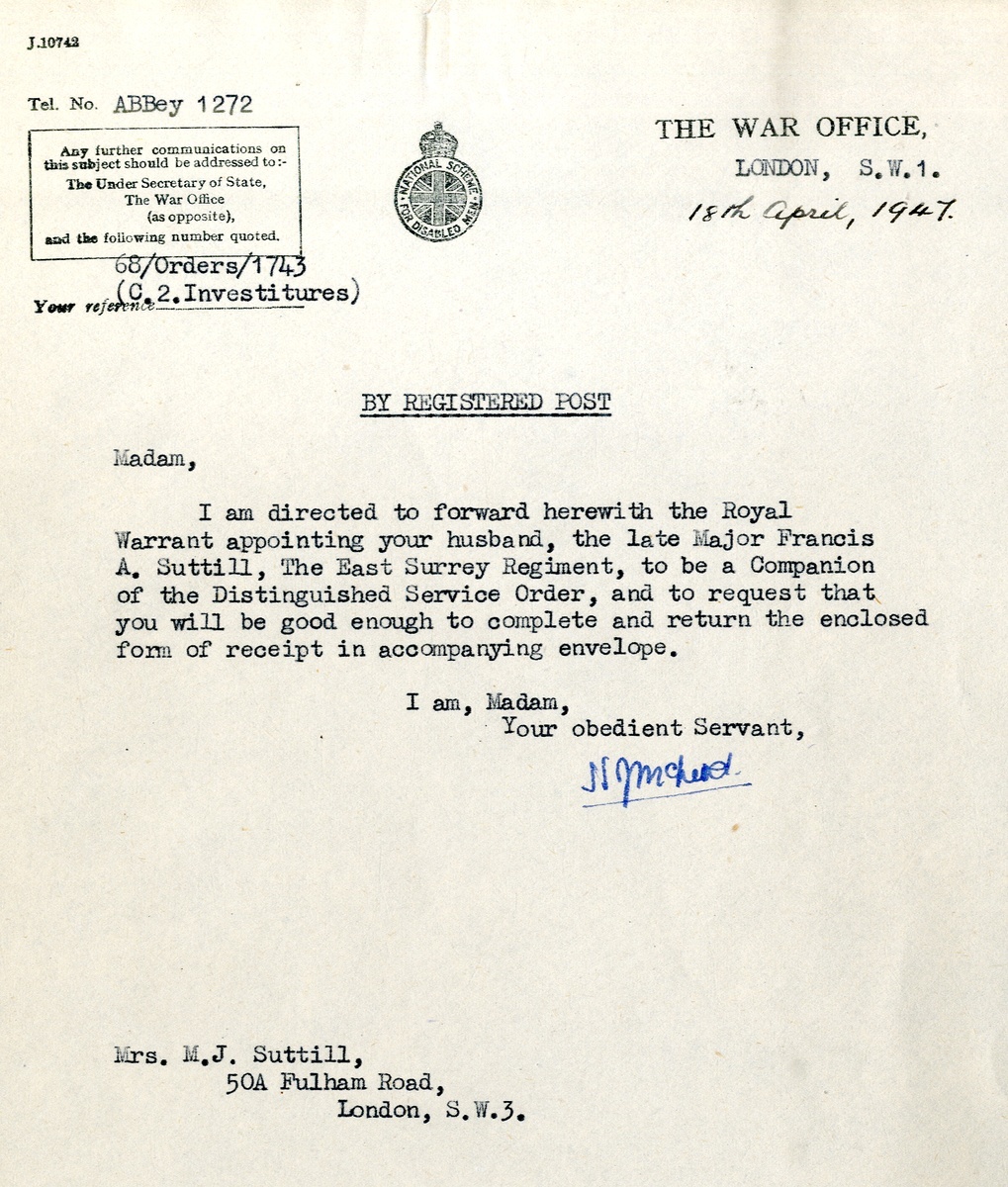

Bestowal Document for the Distinguished Service Order, dated 15 November 1945, in the name of 'Captain (Temporary Major) F. A. Suttill, The East Surrey Regiment', in its O.H.M.S. envelope sent to 'Mrs M. J. Suttill, 50A Fulham Road, London, S.W.3.' and with War Office forwarding letter dated 18 April 1947 (68/Orders/1743 (C.2.Investitures)).

(iv)

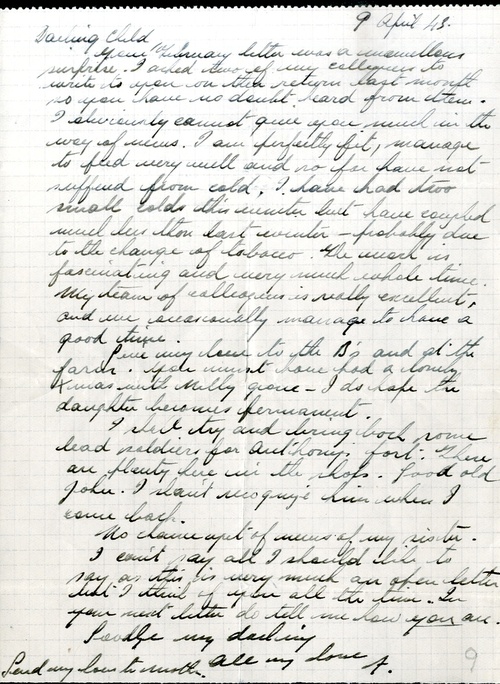

A file containing some sixteen original letters, written by Suttill to his beloved wife, the majority with their envelopes and a number also with their relevant 'War Office, Room 238' forwarding notes. Each letter with a transcription and from which extracts are quoted in the biographical note. To include the moving and most poignant letters prior to his first entering the theatre of war and also his final letter home, written shortly before his capture. Also to include the aforementioned quoted letters from Buckmaster, dated 5 May 1945 and that from Vera Atkins, dated 22 December 1945.

(v)

East Surrey Regiment Collar Badge, silver and gilt, with brooch fittings to reverse. Sold together with a note from the vendor stating:

'An East Surrey Regiment 'collar dog' converted to a sweetheart brooch for his sister Emmeline who wore it all of her life. She was my godmother.'

(vi)

A section of green parachute fabric. Sold together with a note from the vendor stating:

'This piece of a parachute from a drop at Mind in Belgium on 21/22 June 1943 was given to me by Annette Bragot whose father was in the resistance there.'

(vii)

A small stone pebble, sold together with a note from the vendor stating:

'I collected this pebble from the remains of Cell 10 of the Zellenhau in Sachsenhausen Concentration Camp where my father was held.'

(viii)

His original green cloth S.O.E.-issued parachute qualification badge.

(ix)

Selection of East Surrey Regiment Badges and Insignia, besides a Surrey Yeomanry silver spoon.

(x)

Gold Lille medallion, dated '17 Octobre 1918'.

(xi)

Stonyhurst College 1926, Syntax I silver Medal, in its case of issue, the lid inner with gilt details of award and named 'FRANCIS SUTTILL.'

(xii)

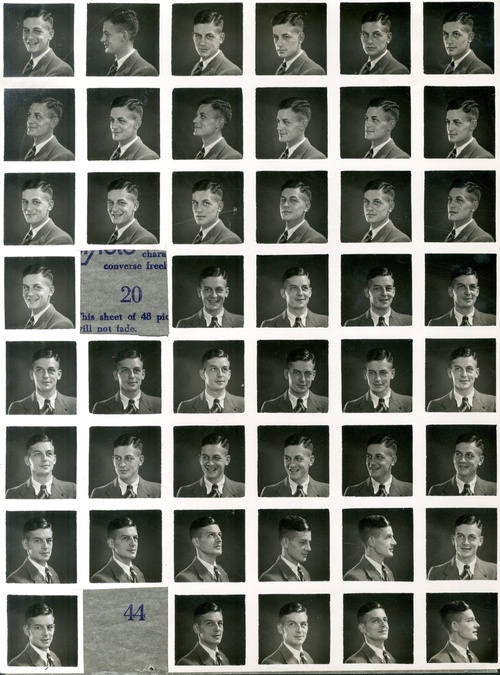

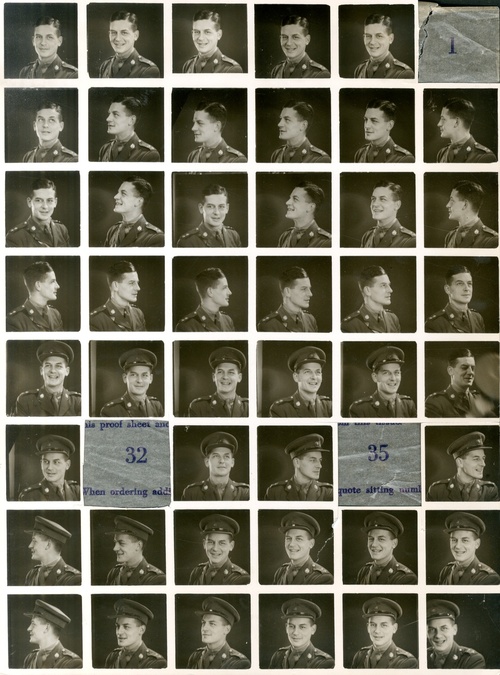

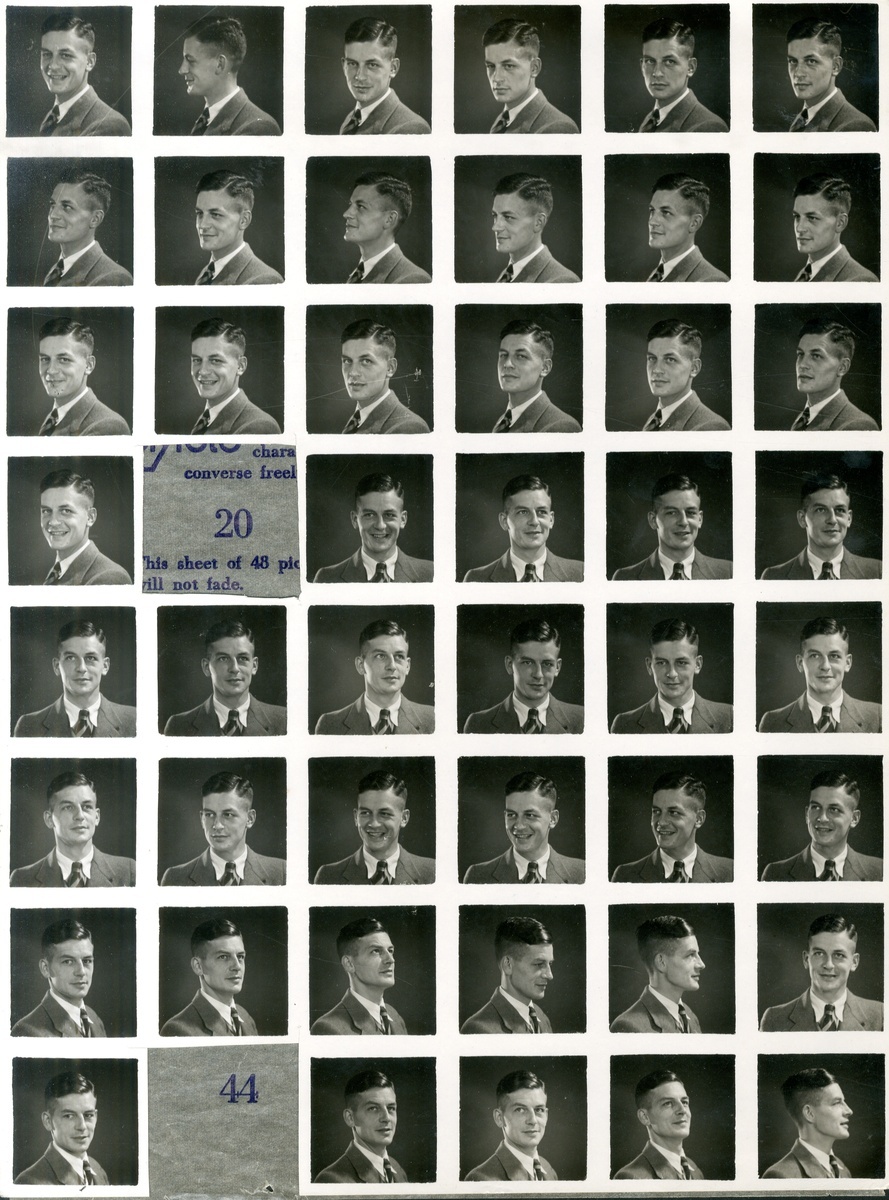

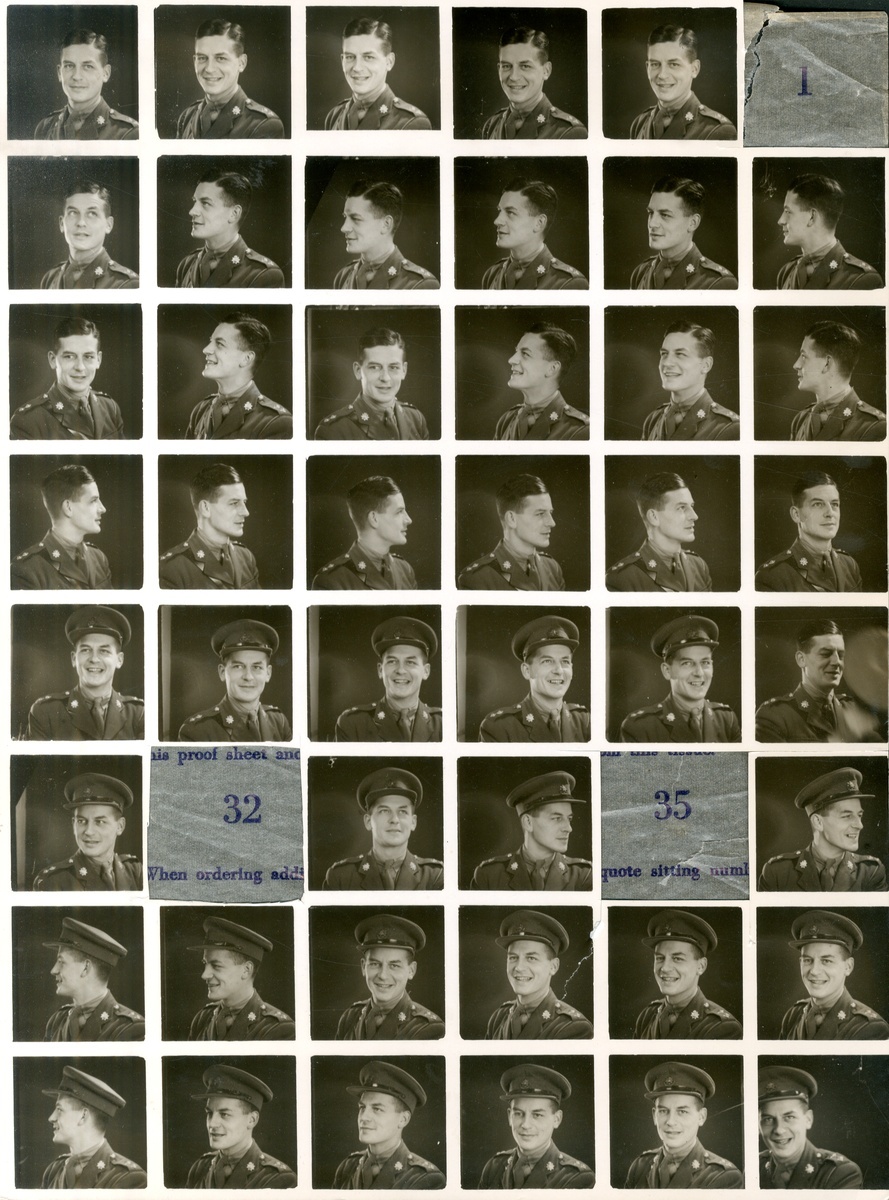

Portrait photograph of the recipient in uniform, the image 155mm x 115mm, by Polyfoto, in large and attractive gilt frame, as retained and used in memorial of him by the family. Together with two original sheets of images from his visit to Polyfoto, with some 45 images in military uniform and 46 in civil dress, these offering a section of previously unpublished images of the recipient.

(xiii)

Small sketch portrait, signed 'CN', in round gilt frame, 165mm.

(xiv)

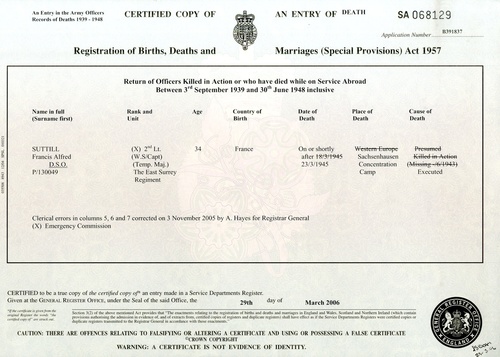

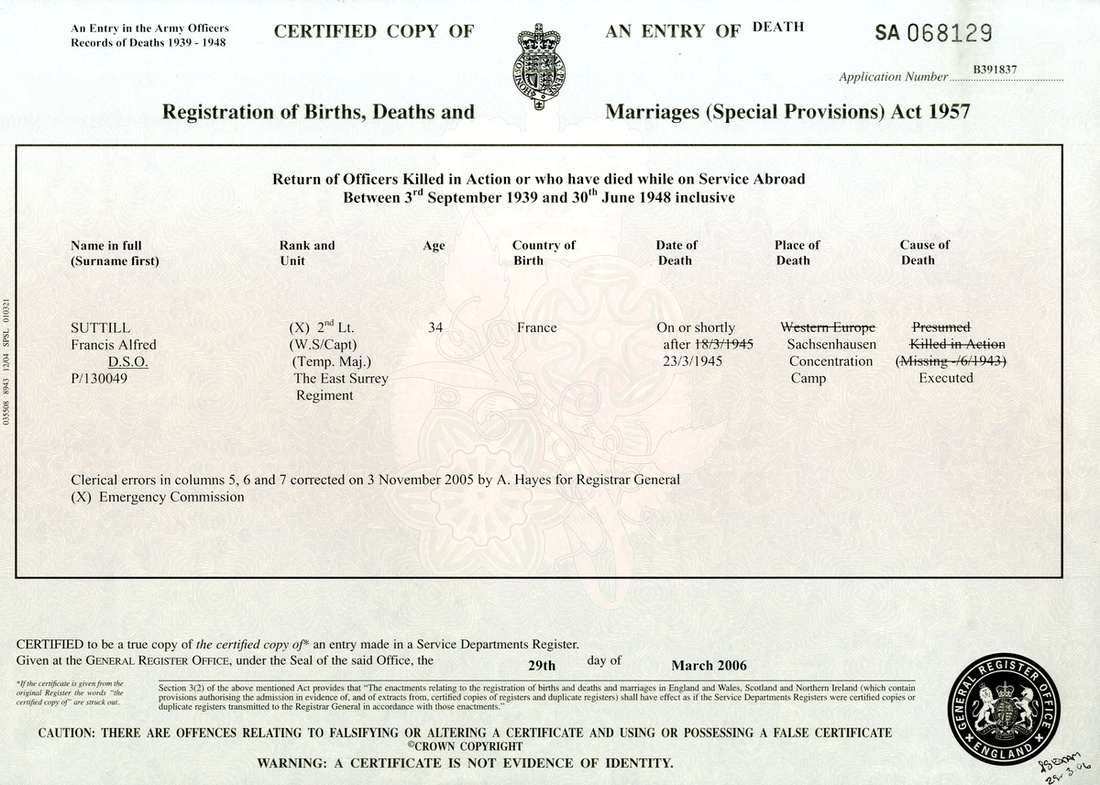

Certified Copy of Death Certificate, displaying the correct details including:

Date of Death - On or shortly after 23/3/1945 (previously shown as 18/3/1945).

Place of Death - Sachenhausen Concentration Camp (previously shown as Western Europe).

Cause of Death - Executed (previously shown as Presumed Killed in Action (Missing -/June/1943).

(xv)

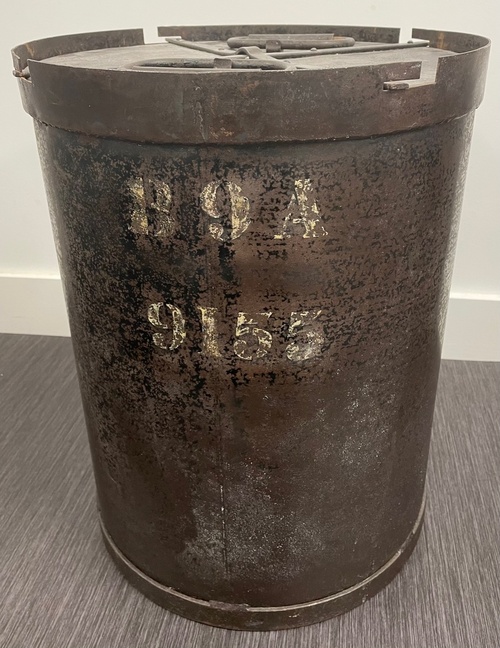

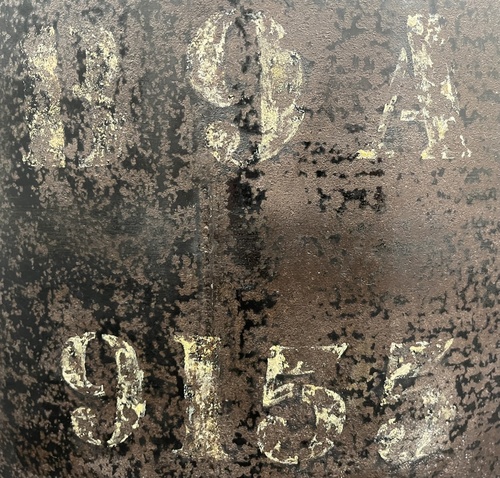

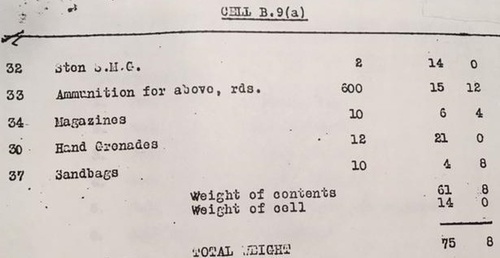

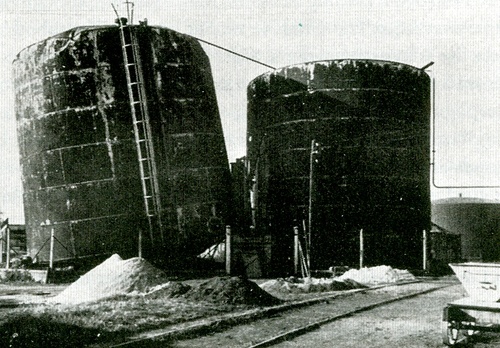

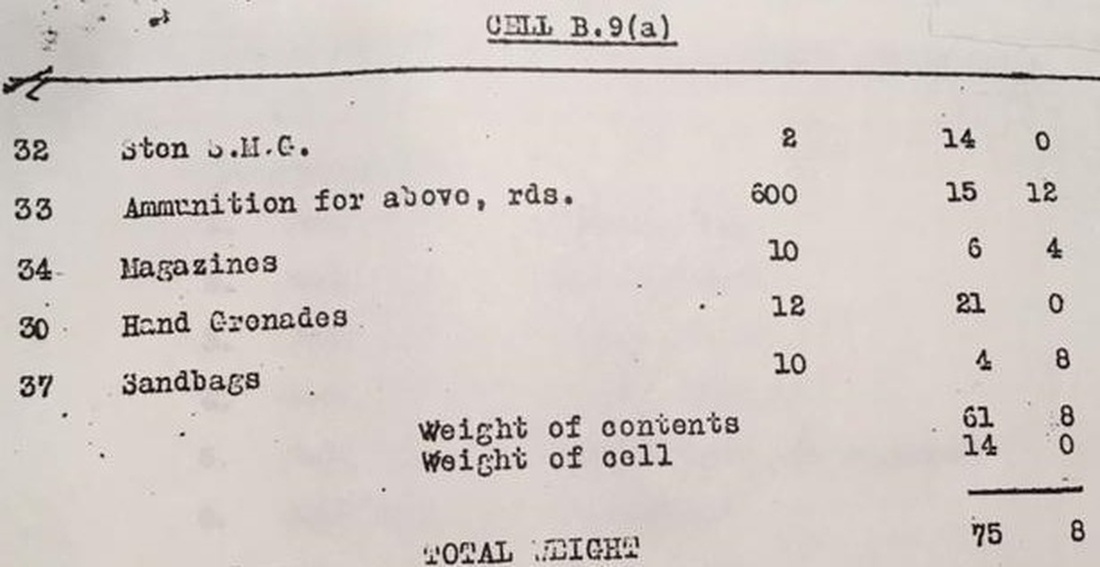

The cylindrical cell, 450mm (high) and 350mm diameter, from a container which was received by the Bordier family at Langlochere on the night of 14-15 June. The metal cell painted black, with painted stencil markings 'B9A 9155' was discovered as recalled by Francis Suttill:

'I tried to find this DZ in 2007 and was just about to give up because the geography of the area had been altered by industrial development and a motorway, when I saw an old man picking fruit. When I told him what I was looking for, he asked me who I was and when I told him, he almost embraced me with delight - he was Jacques Bordier and had helped his father with all three of this groups' receptions...Jacques later presented me with this container as a souvenir.'

The cell was in a poor state and it became the feature on an episode (13 July 2020) of the BBC television production: 'The Repair Shop'. Of its importance, Suttill continues:

'He was Jacques Bordier and, aged 19, he had helped his father with the drops on their farm. He very proudly showed me three cells from one of the containers which he had managed to keep concealed - despite strict orders to the contrary! It was obviously dangerous to keep such items but as a farmer he could not resist a good bucket. Six years later, at a reunion, Jacques presented me with one of the cells, which my family call 'the rusty bucket'. Unfortunately, my father was caught and killed. This cell is the only tangible link that I have to his time in France.

Ever since I was given the bucket, I had thought about how to conserve it and, when I mentioned this to a friend whose grandmother had been one of my father's couriers in France, she told me all about 'The Repair Shop', so I sent them a video and they contacted me almost by return.'

Further research into this specific cell revealed that its contents on that drop were:

'2 Sten Guns, 600 rounds ammunition, 10 magazines, 12 grenades and 10 sand bags.'

(xvi)

His leather gas mask holder and Sam Browne belt.

MAJOR F. A. SUTTILL, by COLONEL M. BUCKMASTER

'Prosper, one of the most trustworthy, brave and resilient Officers that served in the SOE...Francis Suttill was a barrister before the War and the qualities of his mind were those of keenness, coolness and confidence which go to make the successful lawyer; he knew his limitation, and if they were few, he knew them well enough to never go beyond them...Francis and his helpers organised a number of excellent Reseaux and soon they were planning a large-scale sabotage. Their exploits included the destruction of a large stock of German aero fuel which was being used to power bombers attacking London and southern England. Paris was, of course, far and away the most dangerous place in which to work; it was swarming with Germans and with security Police of every description. Nevertheless, Francis fashioned, in the face of every hazard, a model organisation. It attempted nothing beyond its abilities nor failed at anything within them...

Francis was very capable, and could not be - nor want to be - withdrawn because the work was tough. Our men knew what they were in for when they volunteered and my job was to see that they had the tools with which their task might be accomplished; at the same time, however, this was a military operation and while I have emphasised the personal side, I should not have been carrying out my own assignment if I had allowed personal considerations to override tactical ones.

Francis was the best man to do what he was doing and he had to stay there. Of all the men who went to France I think I admired and respected him the most and his death came as a cruel blow to me...yet one cannot pull out a Commanding Officer when the situation gets hot.'

Buckmaster, Head of ‘F’ Section, S.O.E., in They Fought Alone.

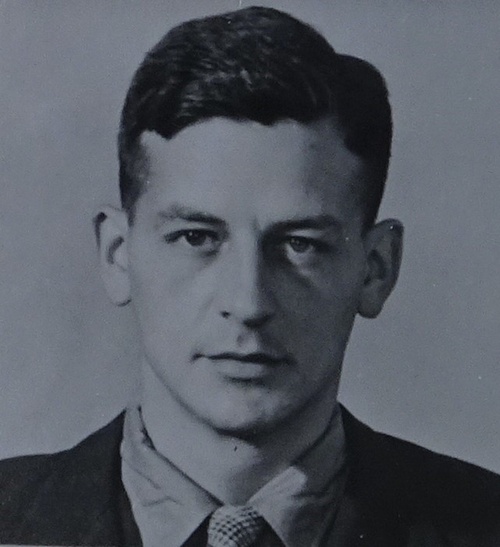

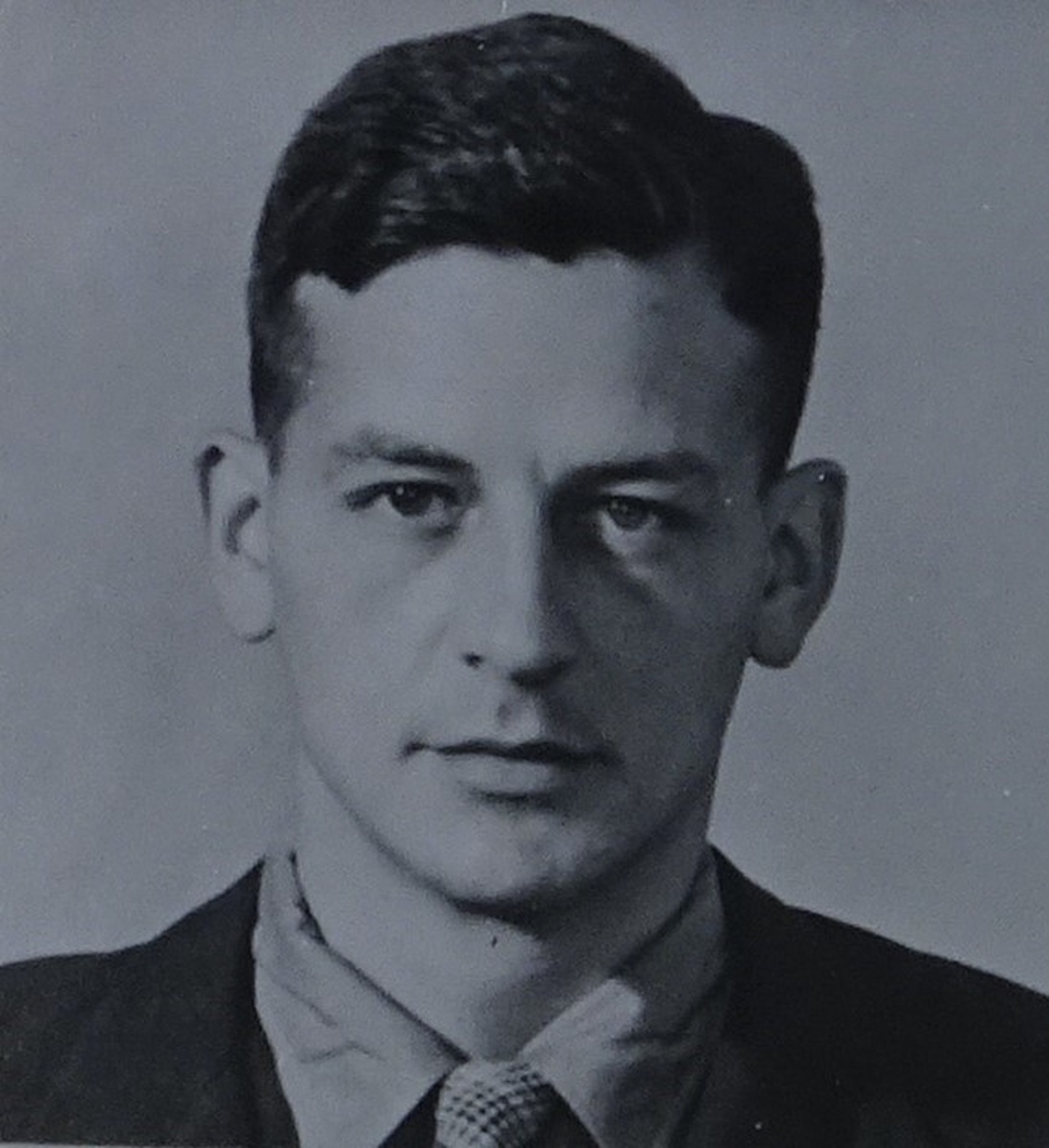

'PROSPER had the clear intellectual vision and logical perspicacity which are often found allied to Gallic features. Dark hair and clear grey eyes, combined with a classic profile, made him striking to the close observer, but it was not until he spoke that one realised the full extent of his charm and balance.

It was a joy to work with a man whose brain cut like a knife into the problems we put before him. He never made the mistake of minimising the difficulties of his mission and he took much care over the study of his brief as if he had found it difficult to understand.'

Buckmaster in Chambers Journal, 1947.

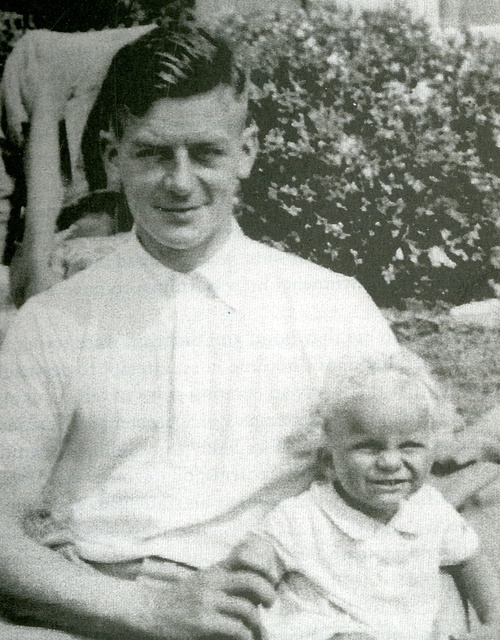

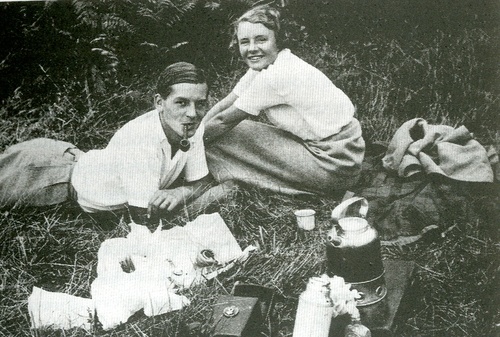

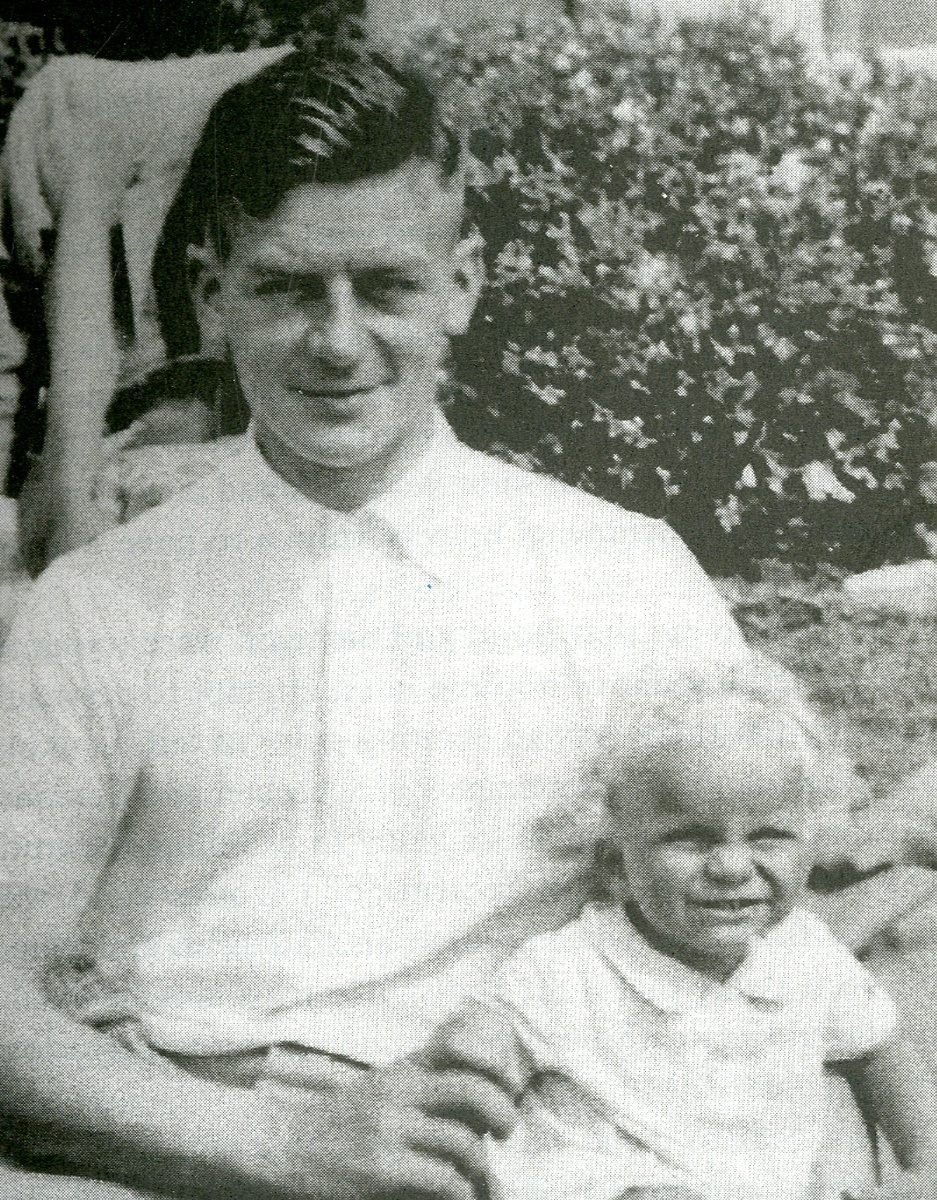

Francis Alfred Suttill was born near Lille, France on 17 March 1910. He was sent to Stonyhurst College, England but in 1926 was struck down with polio. This left him with a stunted leg which remained around an inch shorter than the other - but despite being told he would never walk again his mother was determined that he would not be hindered. He was soon sent out onto the golf course which aided his rehabilitation and he was able to recover without any perceptible limp. From 1927-28 he attended the College de Marcq in Mons-en-Barœul, gaining his Baccalauréat. Reading Law at Lille University, he was an external student at University College, London and was called to the Bar in 1935, the same year in which he married Margaret Montrose, herself a medical student. The pair set up home at Newdigate, Surrey. Suttill had issue of two sons, Anthony (who was born in 1937) and Francis John who followed in 1940.

A Call to Arms

With the outbreak of the Second World War he joined the ranks of his local county unit, the East Surrey Regiment, but given his profession and language skills, was soon singled out for a commission, which he gained in May 1940. Not particularly taking to life in an Infantry Regiment, Suttill found himself posted on an Intelligence course in the Spring of 1941 and was thence appointed the Intelligence Officer to 211 Brigade, Plymouth. This posting took his family away from Surrey and saw them establish a new home base in Devon.

Like so many others, his exact recruitment to the Special Operations Executive (S.O.E.) remains something of a mystery. Suttill was assessed for suitability as a paratrooper at Chesterfield in November 1941 and he was then approached by a Captain Hope Thompson in early 1942. His reply on 24 January 1942 gave his desire to '…volunteer for paratroops and hope that you will remember me if a vacancy occurs in your Battalion. Please recommend me for special duties if you can.'

Stating his native French, the authorities clearly felt this was a match for he was posted Temporary Captain with the Parachute Regiment on 9 March 1942. It was just a week later that appointment was cancelled and Suttill was summoned to Room 055A at the War Office. Little did he know his interview to join the S.O.E. awaited him; he signed the Official Secrets Act on 19 May 1942, becoming 'Fernand Sutton' in the process.

First sent to Special Training School (S.T.S.) 5 at Warnborough Manor, Guildford, Surrey, Suttill came under the charge of Lieutenant Robert Searle who led a group of eleven recruits. Two were swiftly failed and left the S.O.E.; Suttill remained and went up to S.T.S. 23 at Meoble Lodge, Arisaig and onto a short parachute course at S.T.S. 51, Ringway Airfield, at which point he probably earned the Parachute Badge offered with the Lot. He trained alongside Clement Bastable, who would organise SCIENTIST around Bordeaux; Robert Lang, who later assisted Bastable; Louis Legranges, a radio operator who was later captured; Marcus Bloom, a member of PRUNUS; Frederick Chalk, who worked with the Political Warfare Executive; and Noel Hines, who was sent on a solo mission.

Wireless training continued at S.T.S. 52, Thame Park and near the S.O.E. 'finishing school' at Beaulieu, with Suttill being based at S.T.S. 31, The Rings.

Into the Field

With the situation for infiltration to the occupied section of Northern France, recruitment of suitable agents was underway. Suttill himself was to take the field name of Francois Alfred Desprez and was initially given the code name PHYSICIAN. He was allotted number '001.F.'

A restless soul, he wrote regularly at the time and clearly wanted to get himself into the field:

'…I gather the intentions of the authorities with regard to me change several times a day just now. It is a result of the Russian news I think...I rather think my job will not be what I thought I don't think I shall be away for longer at a time than a few days.'

The behaviour of those from different - competing - agencies within British Intelligence are also evidenced. Another letter continues:

'A funny thing. I passed Dansey in the street the other day. He was in civvies & recognised me. We did not [underlined] exchange greetings.'

Dansey was no less than Lieutenant-Colonel Sir Claude Dansey, Codename 'Z', who was Assistant Chief of the Secret Intelligence Service.

The seeding of follow-up circuits after the infiltration of AUTOGIRO were afoot, as was the need for guerrilla warfare, via further operations of the S.O.E. in France. Plans were made by August 1942 to deliver stores and get communications established before sabotage operations could evolve. Given the state of the game, it seemed impossible that any invasion of Europe could be possible until the Spring of 1943 at the earliest.

Suttill was chosen to be the man to break the ground, together with Andrée Borrel, with whom he got on well. Despite his language skills, it had been feared that collaborating Frenchmen might question his accent and thus it was decided he should establish himself with Borrel leading any conversations in the theatre of operations. A suitable cover story regarding his studying in Canada was thrown into his repertoire for good measure in case questions were raised.

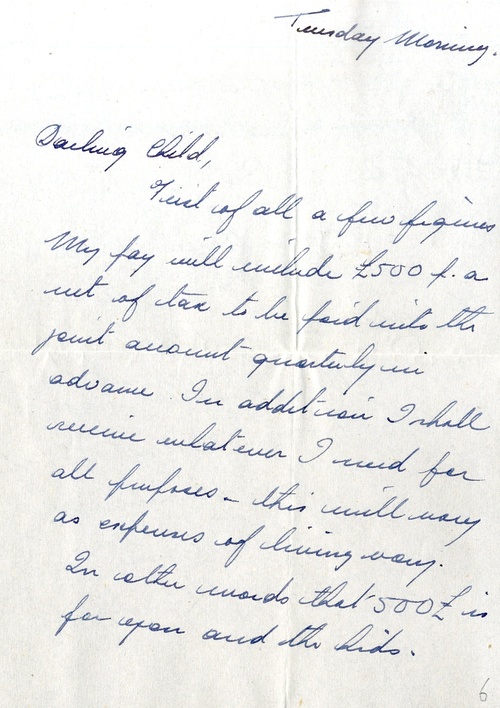

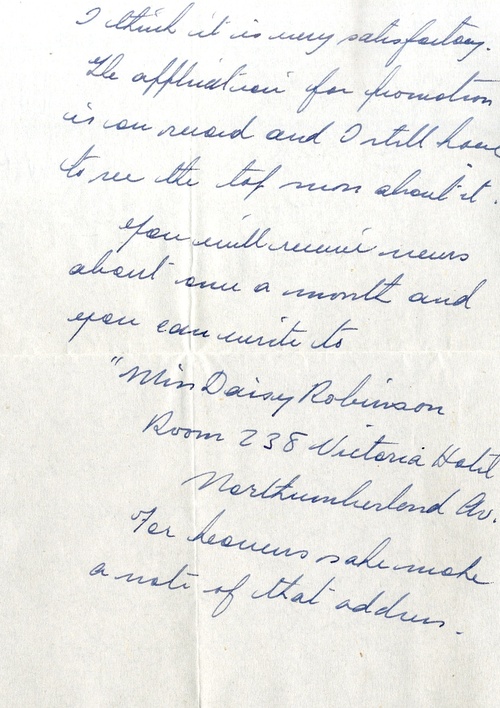

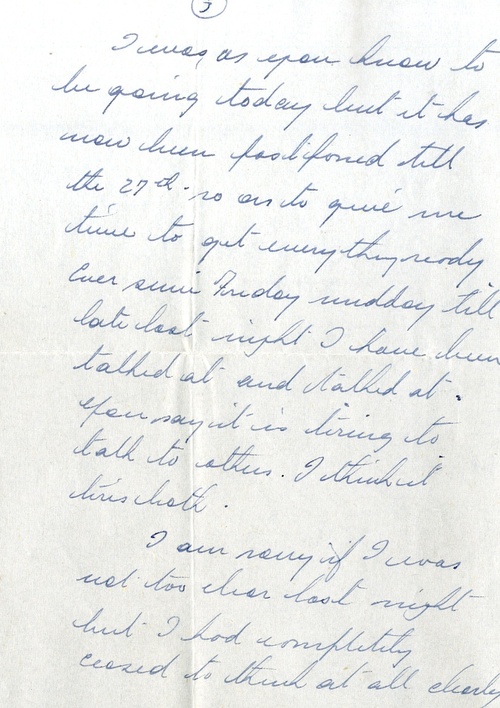

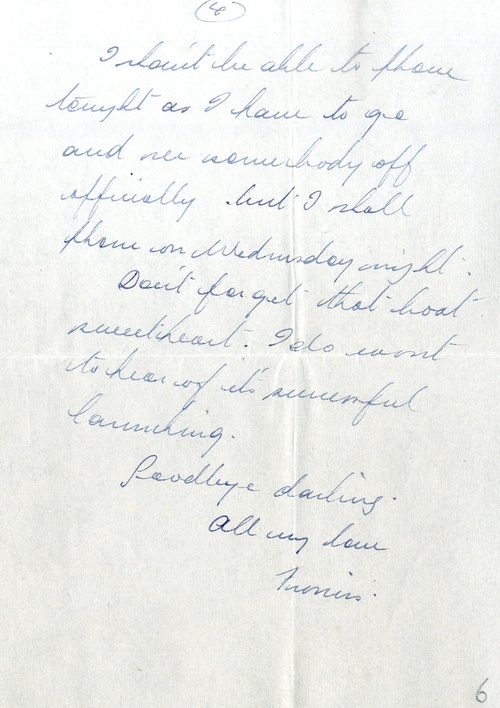

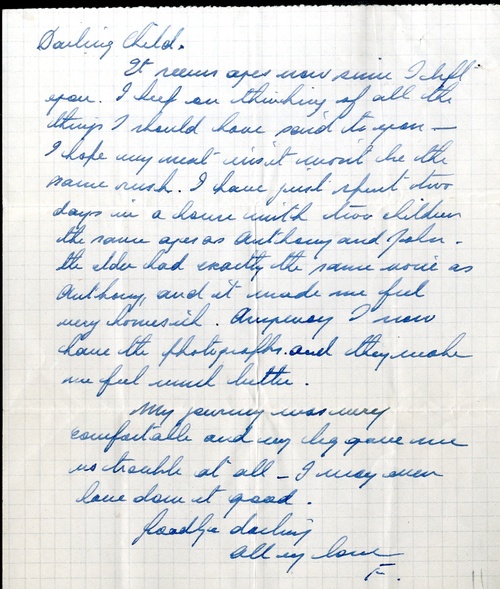

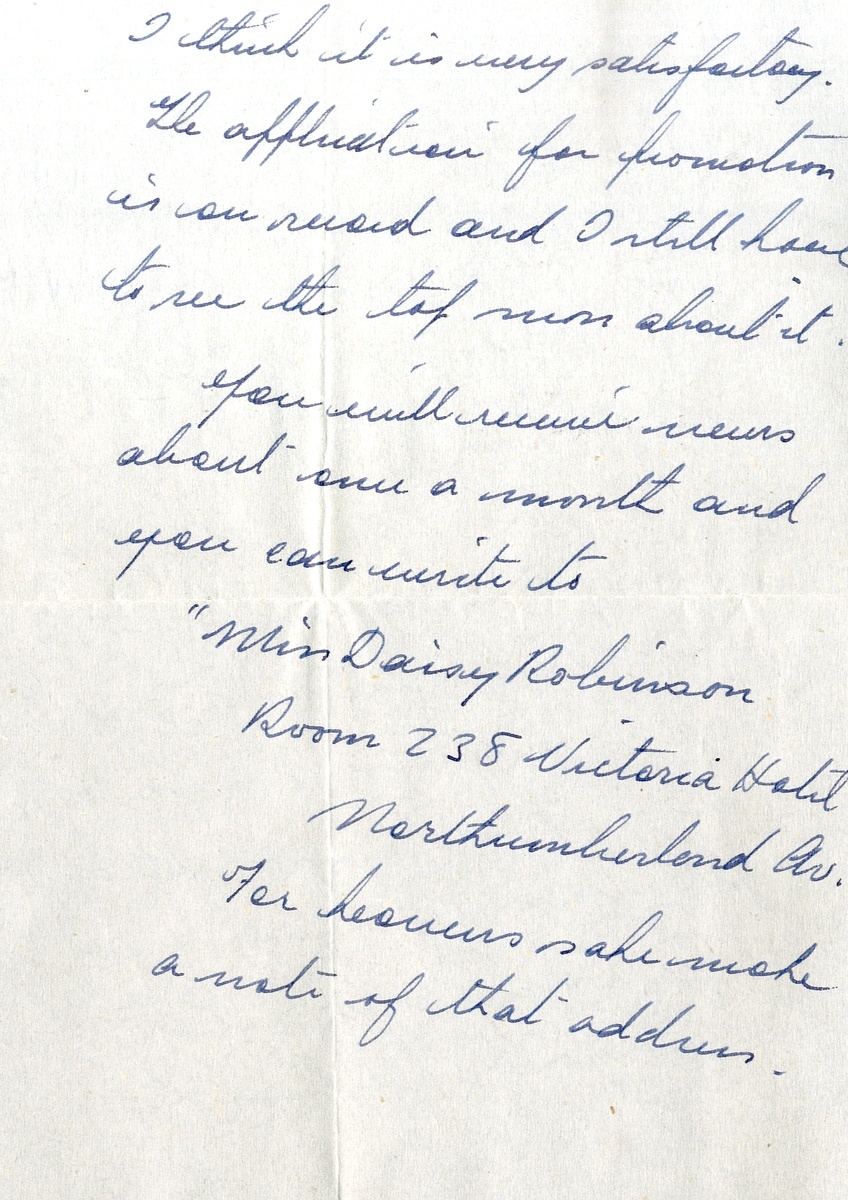

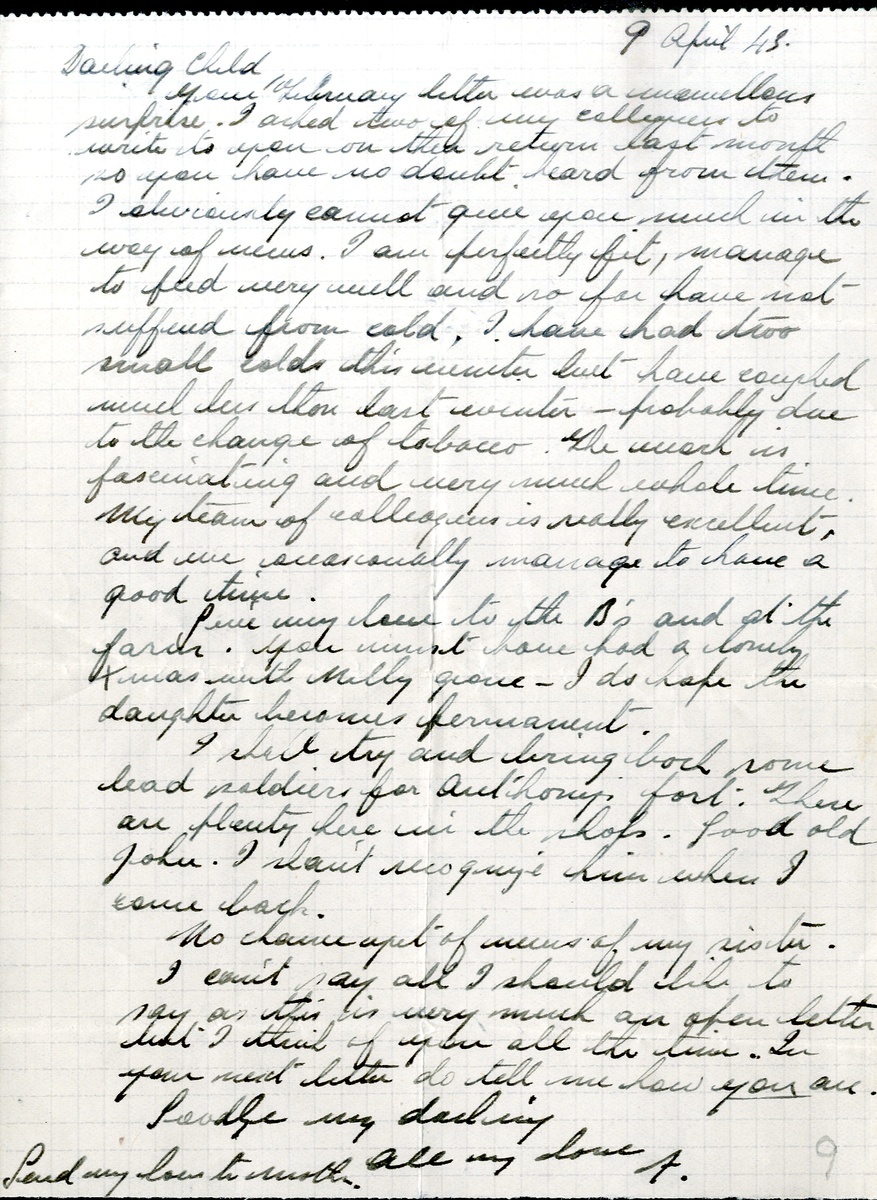

The delays and mental strain must have been remarkable but the letters in the period - all of which his wife is addressed as 'Darling Child' - shed further light. A letter of 22 September 1942 gives practical details of the financial provisions for his family, besides his contact details via Room 238 at the Victoria Hotel, Northumberland Avenue:

'For heaven's sake make a note of that address.

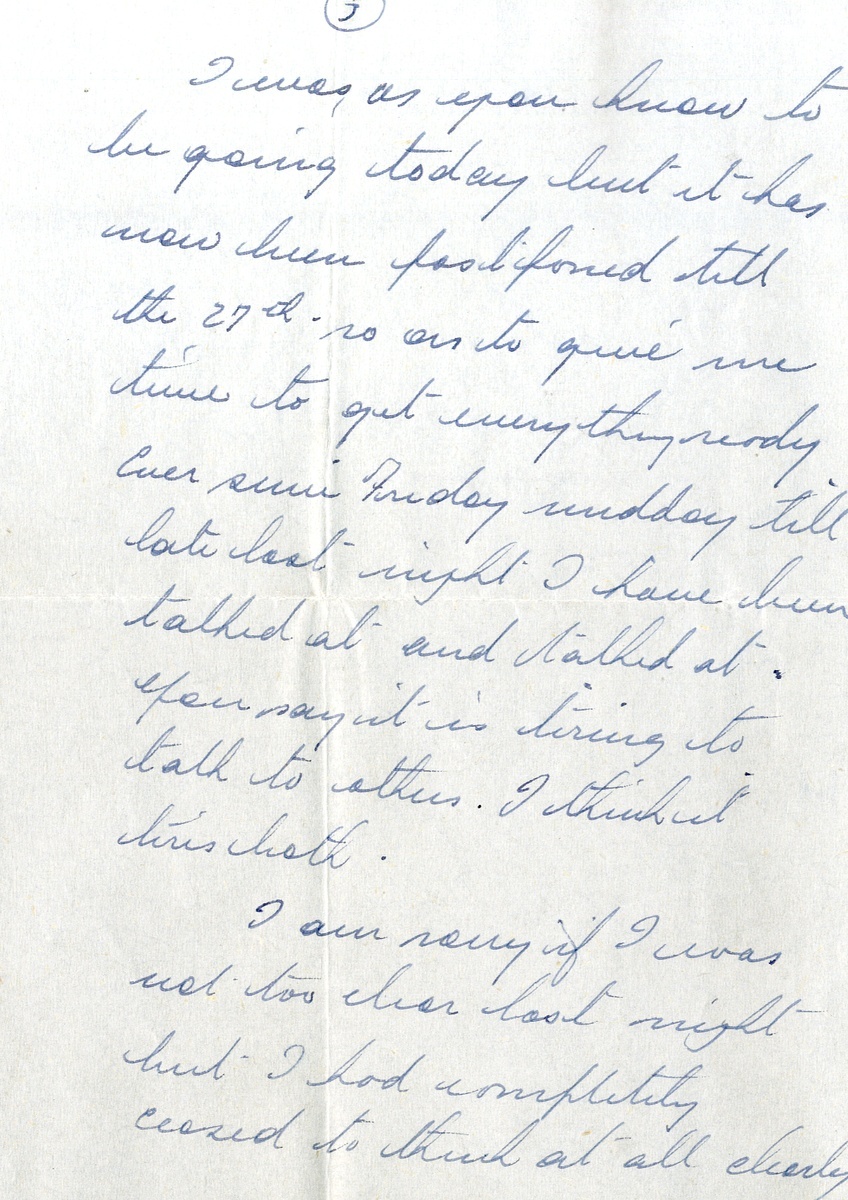

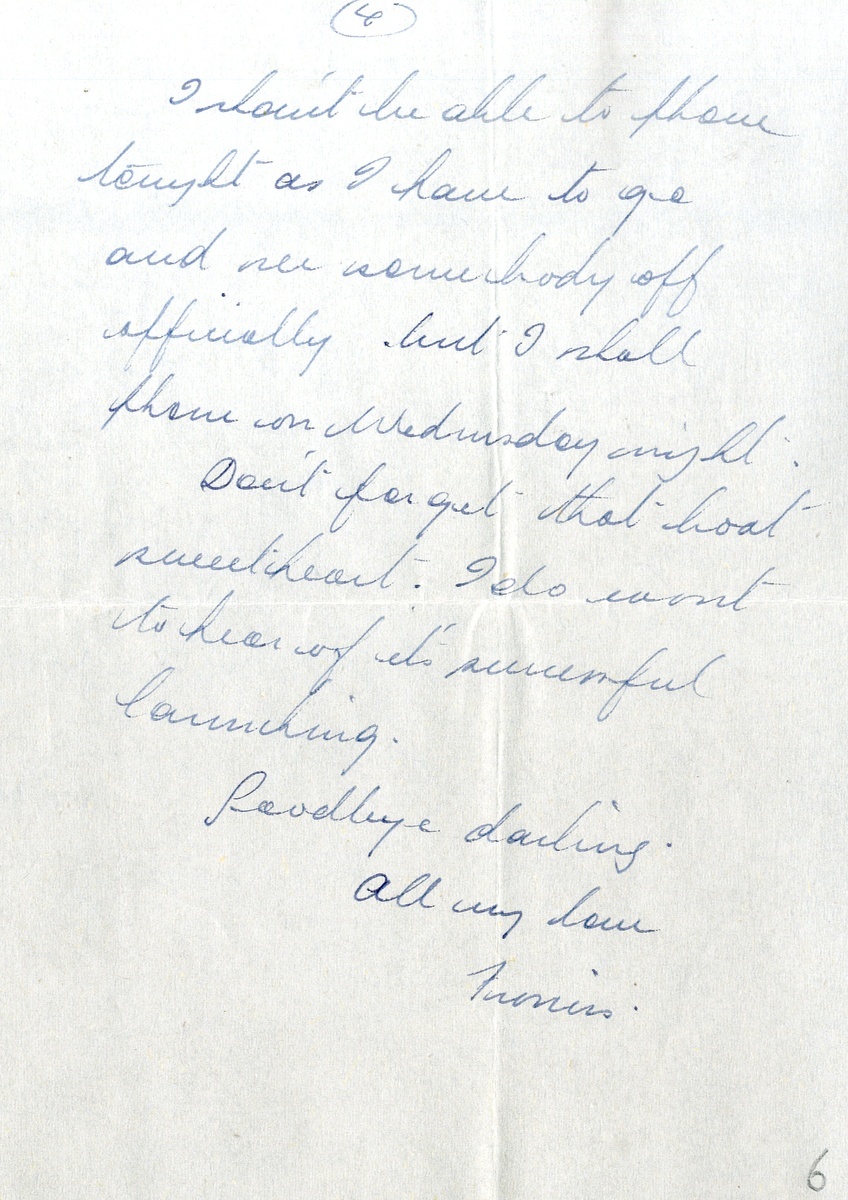

I was as you know to be going today but it has now been postponed till the 27th so as to give me time to get everything ready. Ever since Friday midday till late last night I have been talked and talked at. You say it is tiring to talk to others. I think it tires both. I am sorry if I was not too clear last night but I had completely ceased to think at all clearly. I shan't be able to phone tonight as I have to go and see somebody off officially [Borrel].

Goodbye Darling, All my Love, Francis.'

His departure didn't happen as hoped a few days later. He continues in another letter of 27 September:

'Darling Child,

Before going any further I must confirm two things. First that the amount at Barclays will be credited with £500pa paid quarterly in advance. Secondly my application for Majority at once was not approved but in the event of my demise on this mission my application will be confirmed and antedated so as to carry a Major's Pension.

I am sorry I could not do better but there it is.

I got your letter. Don't worry - I shall have sandwiches and tea on the trip. I may incidentally pass over not very far from you as we do a circular trip to avoid opposition. I shall also have barley sugar.

I do feel a bit foul not for my sake but for yours. Anyway I know that your thoughts and good wishes will always be with me as will mine with yours.

I have a marvellous job and an excellent team under my orders and I will do all that I can to make the thing a great success. Goodbye my Darling and thank you a thousand times for all the happiness you have always given and will always give me. I am the luckiest of men.

Goodbye darling one. Francis.'

His final letter would be sent on 1 October 1942, for he was 'dropped' that night by Flying Officer Anderle of No. 138 (Special Duties) Squadron, Royal Air Force:

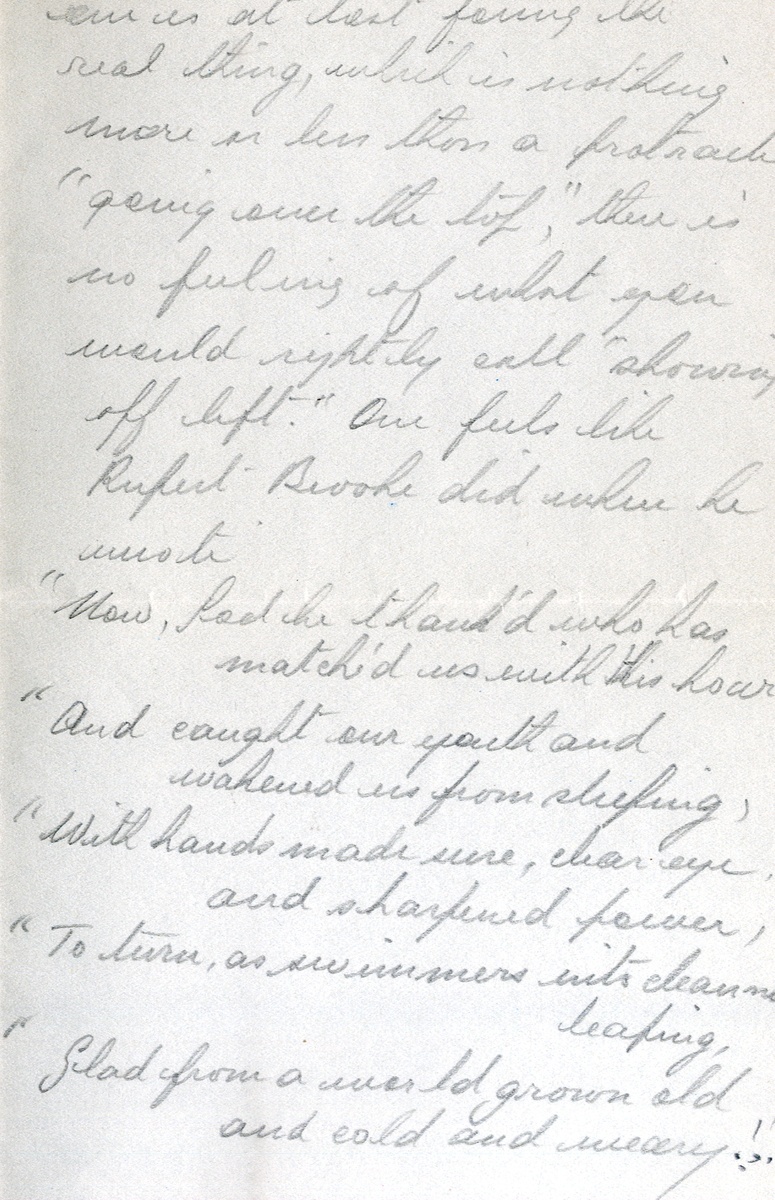

'The last few days have been a queer experience - much easier than when I saw the others off last week. It is easier for oneself than for others. There is also a very pure feeling of exultation - I say pure because when one is at last facing the real thing, which is nothing more or less than a protracted 'going over the top', there is no feeling of what you would rightly call 'showing off'. One feels like Rupert Brooke when he wrote -

'Now, God be thanked who has matched us with his hour, And caught our youth, and wakened us from sleeping, With hand made sure, clear eye, and sharpened power. To turn, as swimmer into cleanness leaping, Glad from a world grown old and cold and weary.'

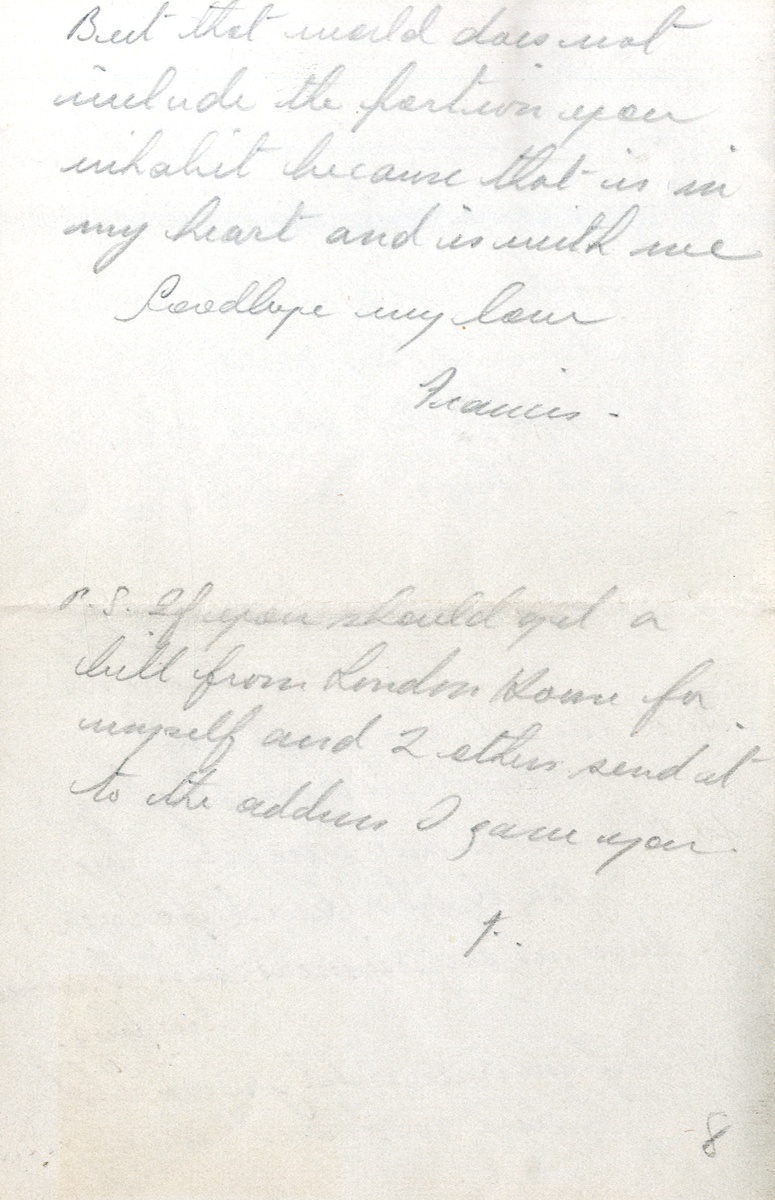

But that world does not include the portion you inhabit because that is in my heart and is with me. Goodbye my love, Francis.'

Low fog greeted him on his blind drop site to the east of Paris and upon landing he was found to be some 12km from the pinpoint and more than 500m from Jean Amps, a jockey from Chantilly, known as CHEMIST. Suttill dislocated his knee upon impact and broke the cartilage where the muscles were atrophied due to his childhood polio.

PROSPER

His codename and that which the circuit he ran was altered at his own request to PROSPER, the moniker of the fifth century Christian writer Prosper of Aquitaine and disciple of Augustine of Hippo. Linking up with Borrel at the café she had described to him on Rue Caumartin, near the Gare Saint-Lazare, they set off to tour northern France and get to work. His mission was summarised by Buckmaster in 1947:

'He had been extremely carefully briefed, for he was destined to become our leading man in France, with HQ in Paris. We wanted to find out the extent to which the French could be relied upon to use arms against the invader, if these were dropped to them by parachute, and if they could be restrained from premature action by the presence of British Officers in contact with Allied HQ in London. We did not expect an immediate answer: we considered that it would take PROSPER six months to form a reliable estimate. We realised that it was be necessary to make trial deliveries of weapons and to perform some specimen acts of sabotage, if only to keep up the morale of the patriots.'

Suttill soon set to work and a number of those under his command were similarly briefed to follow his orders to the letter, expand the circuit and continually communicate with HQ in London.

First Drops

Operation Physician 1 took place at Étrépagny on the night of 17-18 November 1942 and opened the account for the circuit. In the four containers which were landed, its booty totalled some 88lbs of plastic explosives, 24 sten guns, 34 revolvers, 46 grenades, 15 Clam mines and 50 incendiaries. They were soon scooped up by the S.O.E. and, with the help of locals, safely secreted in a barn via the use of a lorry. The cargo later found its way onto a Seine barge and into the city.

A second consignment to the same DZ was planned for the December moon cycle but poor weather on Christmas Eve stopped Jack Agazarian and his wireless set being deposited. They made it on 29-30 December instead.

Alongside the first drops, contact was being made in the region to set up other details for the circuit. Wireless operations and enrolling local resisters went at a pace. With the New Year dawning, further infiltrations of agents and operators continued. Jean Worms and Henri Dericourt - whose names will feature further in the story - were landed on 22-23 January when blind-dropped near Pithiviers, Loiret.

Each drop would be confirmed through the BBC World Service in coded messages and on 15-16 February four containers were dropped after the signal 'La baleina aime les eaux froides' (The whale likes the cold waters) was sounded. In this period their experience and the size of the operational area of scope continued to grow - but not without setbacks. Numerous drops were either aborted or missed for one reason or another.

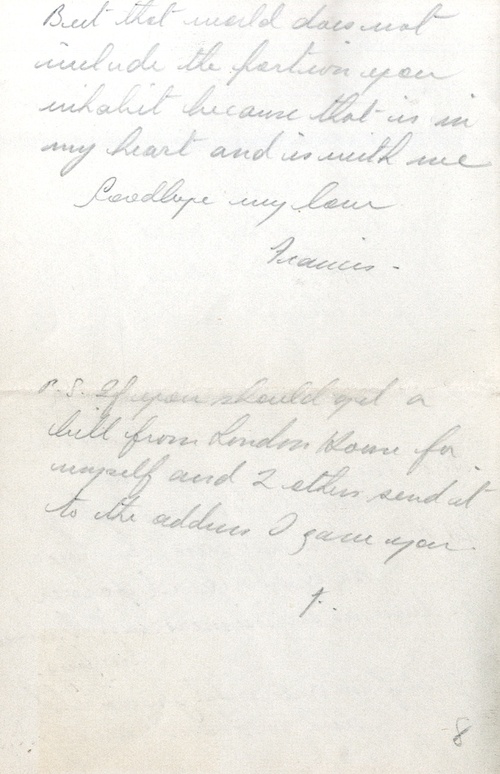

Suttill also got his first letter from his wife which landed in his hands in February. His return, dated 9 April gives a little flavour to his positive outlook:

'Your letter was a marvellous surprise…I obviously cannot give you much in the way of news. I am perfectly fit, manage to eat very well and so far have not suffered from the cold.

The work is fascinating and very much whole time. My team of colleagues is really excellent and we occasionally manage to have a good time. Give my love to the B's [Boy's]…I shall try and bring back some lead soldiers for Anthony's fort; there are plenty in the shops. Good old John, I shan't recognise him when I come back.'

Other figures also entered the stage, such as William Grover-Williams 'Sebastien', a pre-War Grand Prix driver whose path would eventually be tied to that of Suttill. He had, by this point, begun to hold stockpiles of the necessary 'equipment' to start to take the fight to the enemy.

Getting on the Front Foot

Whilst numerous missions were taking place in this period, it is simply not possible to give details about them all and those who wish to explore them further should refer to the cited Reference Sources.

As recalled in the D.S.O. Recommendation, Suttill was responsible for the sabotage on the Chaingy Power Station, reported in the S.O.E. Progress Report of 15 March 1943. Suttill and Norman blew up the transformers with some 20 charges and blew the power for some 11 hours. The same report lists further work by the circuit:

'A train taking foodstuffs to Germany was set on fire and destroyed on leaving Paris.

Three troop trains were derailed near Blois. These appear to have been entirely German and 43 Germans were killed and 110 wounded. As a result, sentinels were placed on the line but these were shot up over a period of ten days.

Bombs were released in the Ministere de la Marine, Place Vendome. Although this was not probably done by our own people, it was certainly done with our materials since no one else has any. This had the curious result that, next day, German sentries were replaced by French.

A bomb was also released in a hotel in the Rue d'Alger.

Incendiaries have also been given to a Police Official to be introduced into the HQ Archives in the Rue Francois 1er.

Germans are killed daily in the streets of Paris and, although once again, this is not done by our people, 90% of these attacks are made with arms provided by us, e.g. to the Communists.'

PROSPER was living up to its name and the appetite to resist and sabotage was clear. However, numerous messages mentioned the need for more arms and materiel to supply the operations: a distinct failure of 'F' Section in February-March. Suttill himself messaged to London with the 'urgent' need for more drops. Another note, from de Baissac's PF File continues:

'This is in some ways a very sad document. The record of achievement and of possibilities is so great but the record of assistance from this side - particularly in the matter of supply - is so small. It is obvious that the stake is big and it is to be hoped that the effort in the next few months will be sufficient to make up the leeway before it is too late.'

Back to Base

The beginning of May saw Suttill return a Progress Report with better news. It arrived on 10 May for the circuit and read:

'Confirms that all of his targets have been reconnoitred and that stores are available.'

However, the size and scope of the circuit had extended at such a rate - no little due to the inspirational Suttill at its head - that nobody at home or in the field might have expected. The length of their lines had put a serious strain on the security around those who were part of the circuit and risked them all.

It was thus Buckmaster who recalled Suttill to London on 15 May, in order to quell surging rumours that an Allied invasion of Europe was simply a rumour. As he recalled:

'The fires of enthusiasm would have to be dampened. Only a first class man like PROSPER could convey that message successfully.'

His diary records the following meetings:

'15th Saturday. PROSPER arrived. Lunch in the canteen.

16th Sunday. Lunched at Carletta's with Prosper.

17th Monday. PROSPER and Colquhoun to dinner at Pelham Court.

18th Tuesday. Lunch with PROSPER at Park Lane Hotel.

19th Wednesday. 1000hrs meeting with PROSPER. Lunch with PROSPER in canteen.

20th Thursday. PROSPER and Renaud (Antelme) left.'

Pelham Court was Buckmaster's own private flat and the frequency of their meetings in this short period surely displays the pressure both men were under to decide the future of PROSPER, not just the man but the circuit too. The identity of Coloquhoun remains a mystery and is probably another S.O.E. agent who was invited to dinner in order to gain a first-hand account from a seasoned field agent. A search of the PF Files suggests Ivo Hugh Colquhoun Hutchinson as a possibility.

Second Innings - Final Throws

Suttill was dropped back into France by parachute with Antelme at the Mirallon DZ near Chaumont-sur-Thronne. Operations continued apace, with the drops of containers becoming more efficient and regular. Besides this an attack took place on the Sucriere Sayat, an alcohol factory in Etrepagny, in which some 6 million litres of alcohol were claimed destroyed. This sabotage was undertaken by the Alavoine brothers for PROSPER. The Progress Report of 24 May stated:

'The organisation has made excellent progress particularly during the last two months. Physician's short visit to this country has been of immense value.'

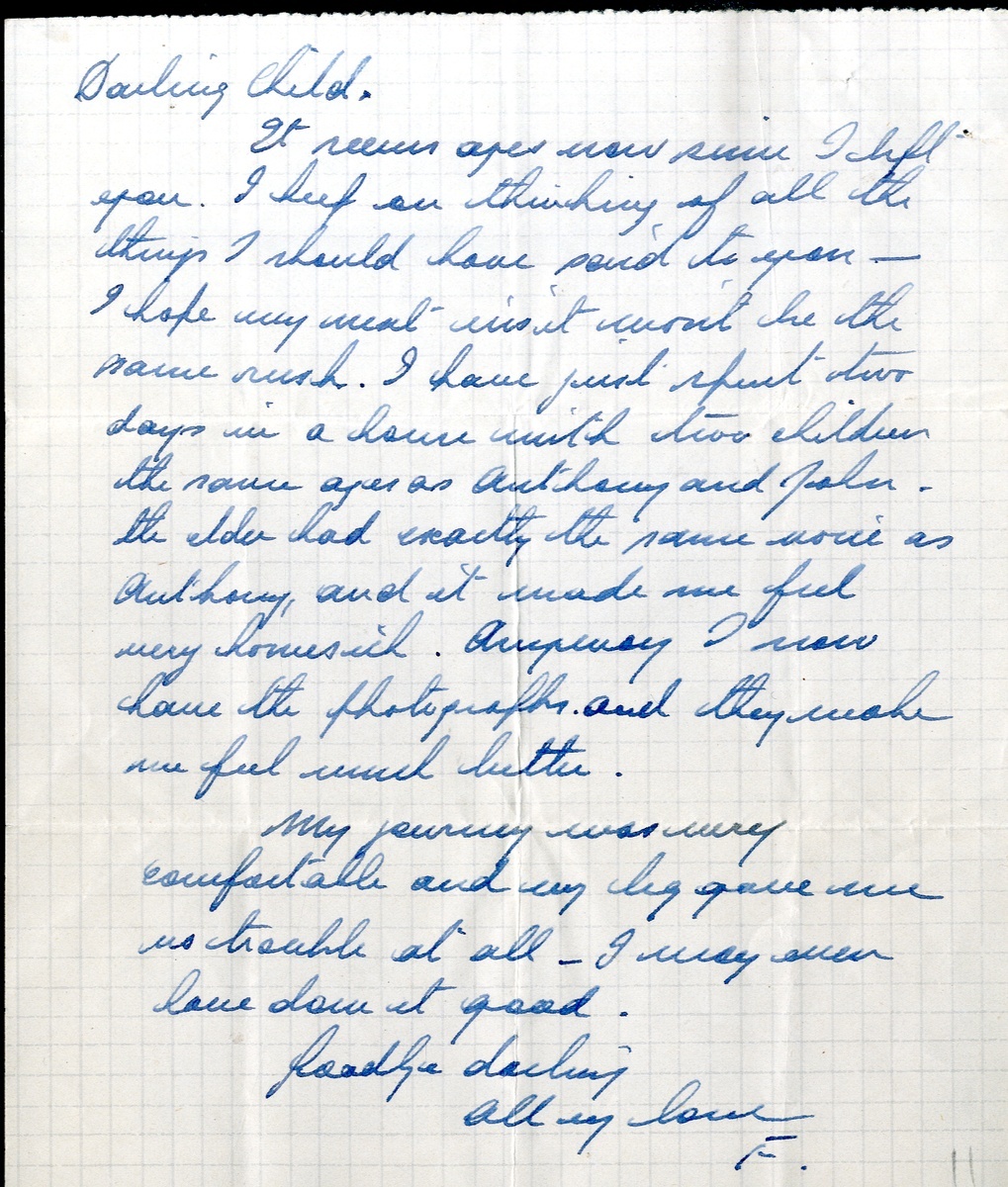

He also wrote home, clearly missing his wife:

'It seems ages now since I left you. I keep thinking of all the things I should have said to you - I hope my next visit won't be the same rush. I have just spent two days in a house with two children the same ages as Anthony and John - the elder had exactly the same voice as Anthony and it made me feel very homesick. Anyway I now have the photographs and they make me feel much better.

My journey was very comfortable and my leg gave me no trouble at all - I may even have done it good.'

The record of that period is remarkable, when one considers that by June PROSPER extended to 12 Departments of France, had 33 active DZ's and had landed at least 250 containers, 190 of which arrived that month alone.

When detailing the story of Suttill, mention should be made of the famous S.O.E. female agents of the Second World War. Three of their number were awarded the George Cross - these being Violette Szabó, Odette Sansom and Noor Inayat Khan. Khan was a member of PROPSER and descended from a noble Indian line and could count Tipu Sultan, the 'Tiger of Mysore', as a direct relative.

She had arrived in France in the summer of 1943 and soon got to work as the first female Wireless Operator within S.O.E.; Shrabani Basu recalls their meeting in Spy Princess:

'The same day she went to Grignon, Noor finally met Suttill in person. He had been touring arms dumps in Normandy between 15 and 18 June and been working on preparing the new identity cards for arriving agents. He'd only spoken briefly to Noor before that. Suttill arrived at Grignon at lunchtime [20 June]. It was a merry Sunday lunch since nearly all the members of the circuit and sub-circuit were present; the Balachowsky's, Norman, Borrel, the Vanderwynckts and their son-in-law Robert Douillet, and the son-in-law of the Belgian Minister. None of the people gathered there, including a happy and relaxed Noor, sensed that danger was just around the corner.'

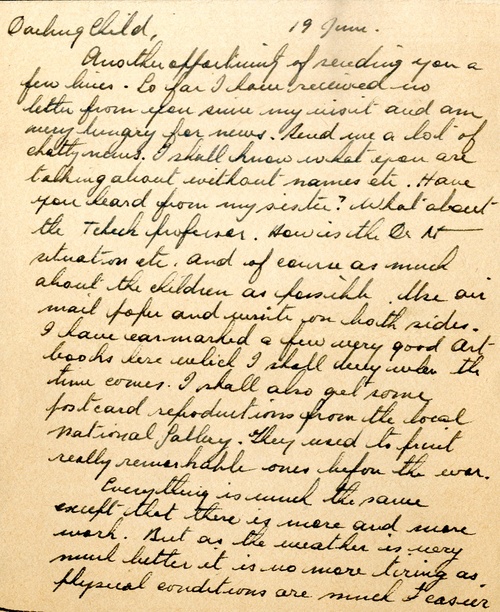

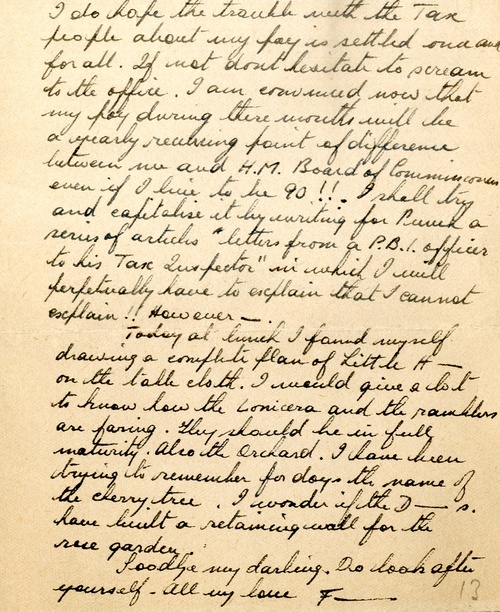

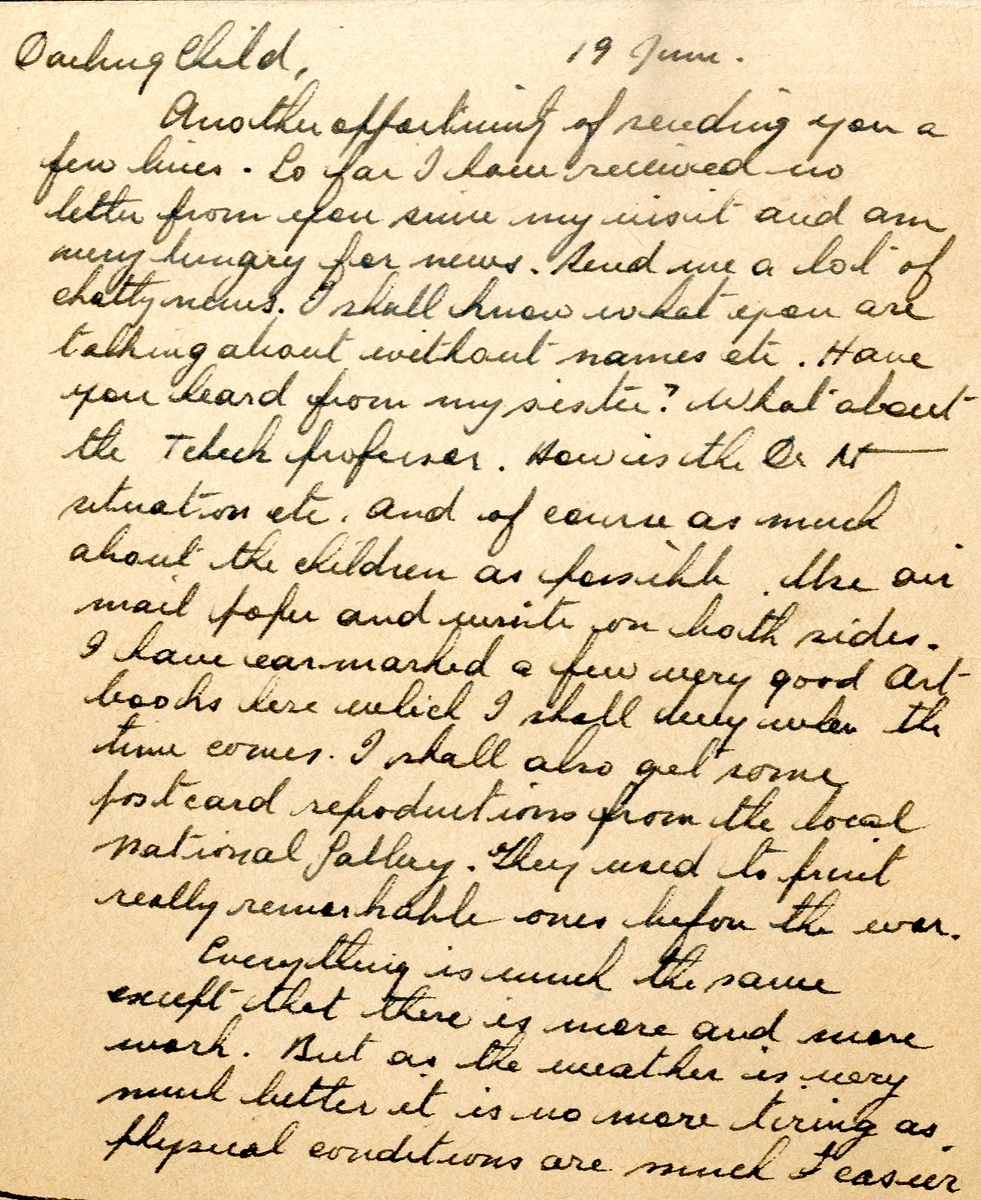

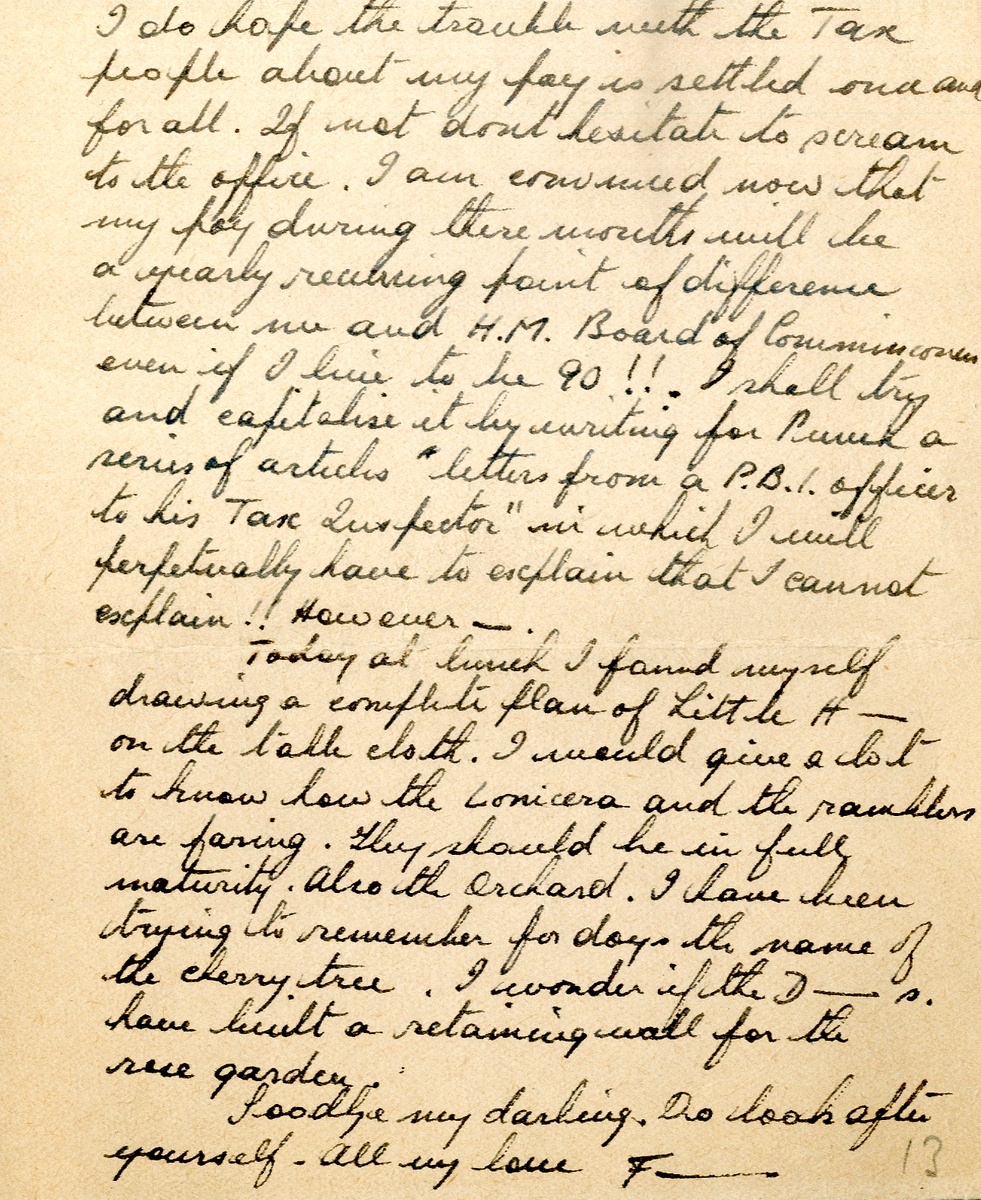

Suttill had written to his wife on 19 June, in what was to be his last letter home:

'Another opportunity of sending you a few lines…Everything is much the same except that there is more and more work. But as the weather is very much better it is no more tiring as physical conditions are much better.

I do hope that trouble with the Tax people about my pay is settled once and for all. If not don't hesitate to scream to the office. I am convinced now that my day during these months will be a yearly point of difference between me and HM Board of Commissions even if I live to be 90!!...Goodbye darling. Do look after yourself. All my love. F.'

The same day he had written to his wife, Suttill also sent a sharp message to Buckmaster, for Khan had nearly been arrested at what proved to be a compromised letter-box. All boxes and their passwords were cancelled. Basu continues:

'Noor had still not received her own Wireless set so she continued to use the transmitter at Grignon…on the morning of 21 June, Suttill met Dericourt and Clement at Gare d'Austerlitz to plan the handover of SOE agent Heslop of the MARKSMAN circuit and an airman…that same night (21-22 June), Suttill, Professor Balachowsky and members of the reception committee had to go to a farmhouse at Roncey-aux-Alluets near Grignon to receive some parachute drops.

One of these contained Noor's transmitter and a suitcase with her personal effects. Unfortunately the parachute came down on a tree and the suitcase burst open spilling all her clothes on the branches. It was crucial to remove all the evidence, so the men had to work into the early hours carefully retrieving each item and repacking it in her suitcase.'

At this point the net was beginning to close in on PROSPER, with drops failing and arrests starting to occur. Two Canadians - Macalister and Pickersgill - had been dropped on 15-16 June into Culioli's DZ laden with suitcases. Whilst in transit they were unlucky to be picked off at a roadblock and found with letters, instructions and radio crystals which were for the attention of Archambaud (Norman Gilbert). Worst of all, it transpired that the delivery address was also enclosed.

Thus on the night of 23 June, members of the Gestapo disguised as the Canadians arrived at the flat of Nicolas and Maude Laurent which had Norman and Borrel inside it. The pair were working on their latest batch of false Identity Cards. The doorbell rang just after midnight and revolvers were drawn. Ten to twelve members of the Gestapo stormed in and swept them up.

The collapse of PROSPER was in full flow and Suttill was picked off from 18 rue Mazagran the next day (with Mme. Fevre being held by the arrest team), they were able to strike and arrest him. By all accounts he put up a heroic fight in the process but stood no chance. Fevre recalled:

'…some two hours later he appeared to me all disfigured, having the appearance of have been beaten and being terribly miserable. When I got my room back the following Sunday, I realised that the Germans had destroyed everything. The marble slab of the fireplace had been torn off and broken.'

At the time of his arrival at 84 Avenue Foch, home of the S.D., Suttill also had a broken arm. The same day Davesne and Lhomme in the Oise had been captured and Culioli was taken almost by chance in Paris too. Scores of the network continued to be picked up but it was upon Suttill and Norman that the fiercest interrogations fell. They were singled-out and questioned without sleep for two days. One of the Secretaries at Avenue Foch commented:

'They did not take to PROSPER much, who had been very English and haughty under interrogation, and that he had just sat in a chair and smoked cigarettes.'

At this point the exact nature of the conversations remain unknown. Certain post-War accounts by Kieffer (the most senior Officer) suggest that Norman gave a full statement on the Operations and network whilst Suttill retained his integrity. The game was clearly up and one can imagine the S.D. requested that unless they assisted with the investigations the consequences would be grave. They would have been made fully aware of the party who were already held, not to mention those who were clearly compromised and remained in the field. Nobody need be reminded of the famous Kommandobefehl (Commando Order) issued by the OKW in October 1942. This effectively gave the S.D. the authority to execute anybody associated with PROSPER. Michael Foot, in a letter to Maurice Buckmaster on the publication of the 2nd Edition of his work on the S.O.E., which was to be passed to the Suttill family in July 1969 concluded:

'It is, that I now have no shred of doubt left that his personal integrity, his loyalty to his friends and his patriotism all remained absolutely intact, to the end. I am quite sure that he was no party to making or sanctioning or implementing any sort of bargain with the Germans, and everyone I met, whether among the senior survivors of the circuit, or elsewhere in F Section who had known him well, spoke most warmly in praise of his character and his courage.'

Dr. Goetz had the crystals in his possession and would be able to lead London as he wished, continuing the deception long after the circuit was blown.

Further arrests followed, with Khan being taken into custody in October 1943. Despite numerous gallant attempts to escape, she would be transported to Dachau and executed along with Yolande Beekman, Madeleine Damerment and Eliane Plewman on 13 September 1944. She was duly awarded the George Cross.

The role of Dr. Goetz is also worthy of note for he was the wireless expert at Avenue Foch and used the radio crystals to perform 'Funkspiel' to London for a long period afterwards. The deception was that the network was still active, and he was able to direct drops of both arms and agents directly into enemy hands. Buckmaster continued in the hope that the gallant band of operators was still secure and the wireless transmissions from London even reminded those in France to complete their security checks, even though it was the Germans operating the sets. As such, unfortunately at least 15 agents were captured on landing.

Against the wishes of the S.D., the German Government forced them to send the following message directly to Buckmaster on 6 June 1944, following the D-Day Landings:

'We thank you for the large deliveries of arms and ammunition which you have been kind enough to send us. We also appreciate the many tips you have given us regarding our plans and intentions which we have carefully noted. In case you are concerned about the health of some of the visitors you have sent us you may rest assured they will be treated with the consideration they deserve.'

It would not be fitting to continue the story without addressing the role of Henri Dericourt, offering some personal views which are based on the evidence available. Some have suggested he was a double agent for the S.D. - though some even went as far to suggest that he was a triple agent, in a vain attempt to continue to keep the network at large. Whatever the truth, it is clear some collusion occurred. He certainly allowed copies of paperwork under his control fall into enemy hands and numerous, seemingly glaring coincidences, happened under his watch. Most obvious perhaps was the arrest of Khan, who had been promised that she would be lifted from the scene.

Of those who worked with Suttill, Norman was executed at Mauthausen concentration camp on 6 September 1944 and Borrel was injected with phenol at Natzweiler, together with Vera Leigh, Diana Rowden and Sonya Olschanezky on 6 July 1944. Their bodies were burned later that day. Borrel had been made the Second-in-Command of PROSPER in March 1943.

Journey's End - Sachsenhausen

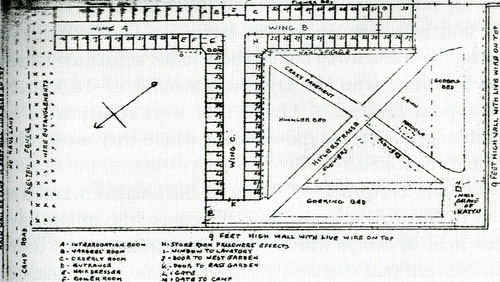

Suttill was taken from Paris to Sachsenhausen Concentration Camp and arrived there on 3 September 1943. Based some 17 miles north of Berlin, the camp had begun being constructed in July 1936, a month before the famed 1936 Berlin Olympics began. During the Second World War it housed around 200,000 inmates and its operators were responsible for the deaths of 100,000 people.

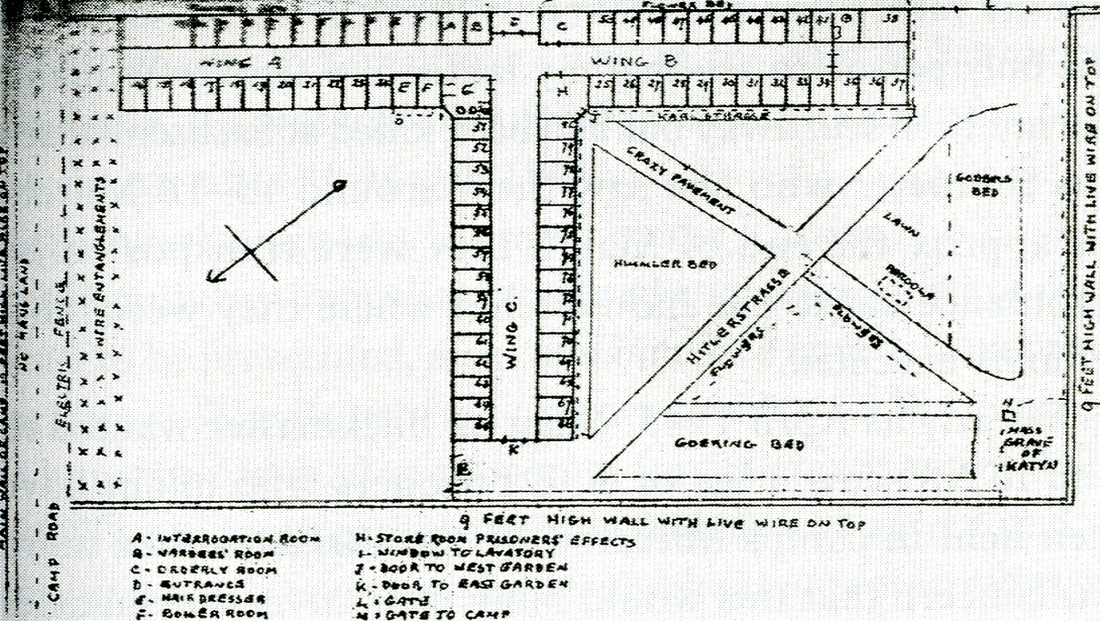

Within the Camp stood the Zellenbau, a self-contained compound of 80 death cells, surrounded by a 9ft wall topped with electric cables. Its building was a T-shape with three corridors meeting in the middle by the entrance. The central area housed an interrogation room which was more than regularly in use. Despite the inmates being imprisoned in solitary confinement, a successful air raid in March 1944 forced them briefly into a bomb shelter. There Suttill would have crossed paths for the first time with the likes of Captain Sigismund Payne-Best and Wing Commander Harry 'Wings' Day, who had led the 'Great Escape', together with three other Stalag Luft III veterans in Flight Lieutenants Sydney Dowse and 'Jimmy' James, besides Major Johnny 'The Dodger' Dodge and the legendary Lieutenant-Colonel 'Mad Jack' Churchill. Other inmates included Molotov's nephew, several members of deposed Eastern European Royal Families and German dissidents.

Their cells were 7ft x 5ft, with a bucket as their latrine and frosted glass with wire on the inside, with just 15 minutes of outdoor exercise permitted each day. They were fed on just 'wurzels cooked in water' so were simply wasting away. Suttill was given Cell 10 and was next to William Grover-Williams, a pre-War Grand Prix driver who had taken the chequered flag on no less than seven occasions. He was a fellow 'F' Section man and was captured on 2 August 1943.

Some prisoners were lucky to be transferred out from the Zellenbau, including Max Mikkelsen, who briefly caught a word with with Suttill before his release on 28 February 1945. He managed to pass him the only piece of contraband he was able to procure, that being a pencil.

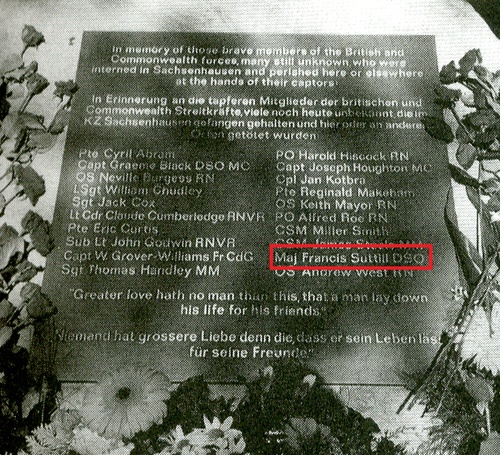

It is now evident that Suttill, together with Grover-Williams, besides an Italian, Bacigalupi and a Norweigan, Nilson were all executed on 23 March 1945.

Two possibilities exist as to their grisly demise, either that the men were hung or shot. The former does not bear thinking about, for the preferred method for hanging at that time was to link the victim via a wire collar to a meat hook. In his book his son has suggested the evidence suggests that his father would have been escorted to the Industriehof. Their captives were under the pretence of a medical examination at which point they would be told to strip and requested by a 'Doctor' to stand against a wall to have their height measured. When the measuring bar touched the top of their head an SS man would fire though a slit in the wall in the execution chamber, with loud music used to deaden the noise.

Another suggestion was the party were stripped and led to an 'execution trench' to be shot. Either way, the gallant life of Francis Alfred Suttill ended on 23 March 1945, when his body was noted as '…released to the crematorium'.

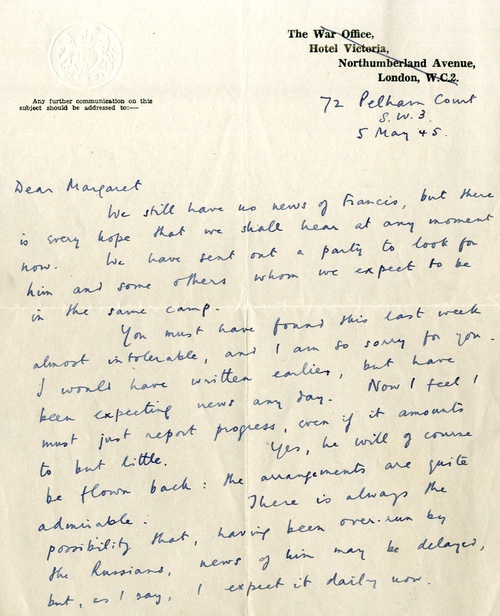

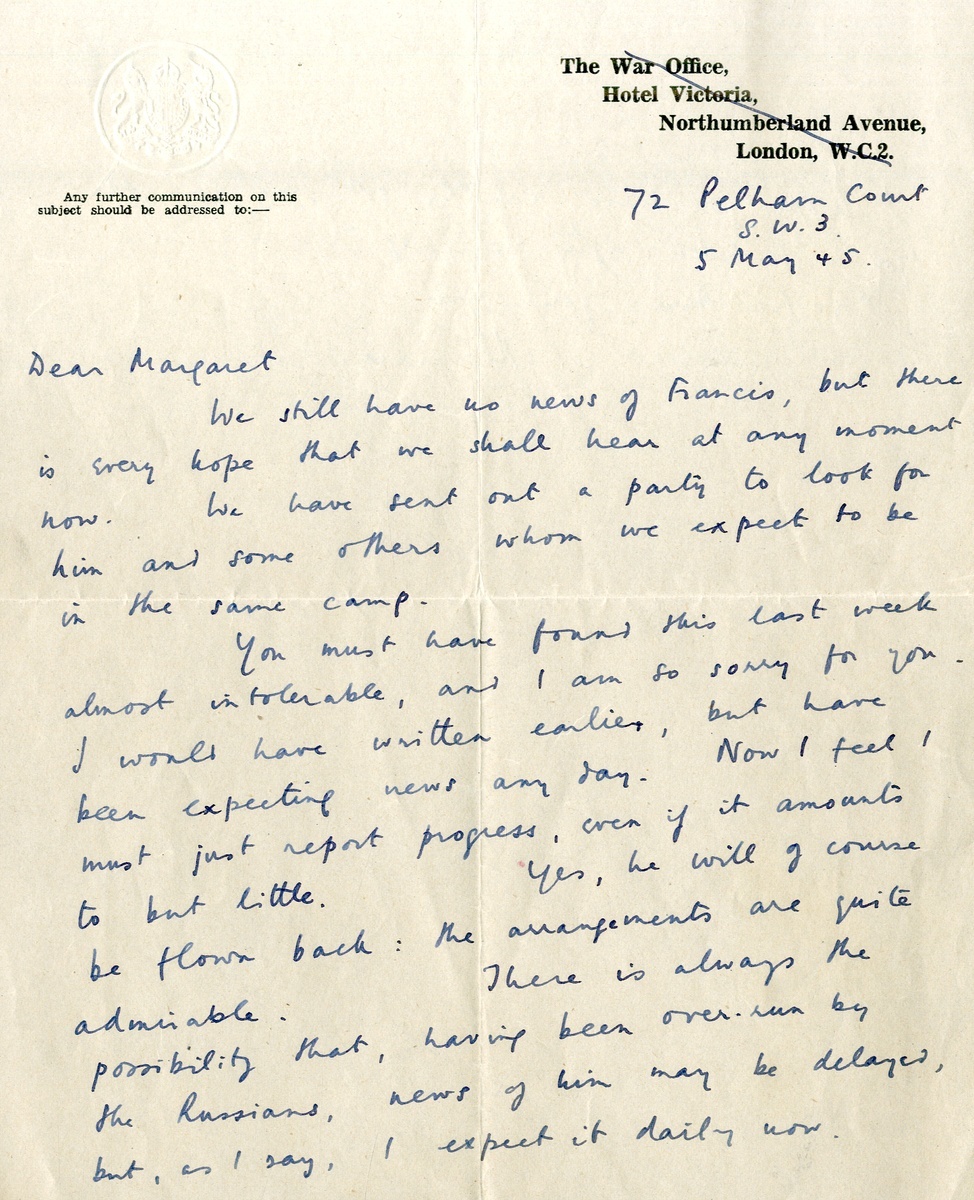

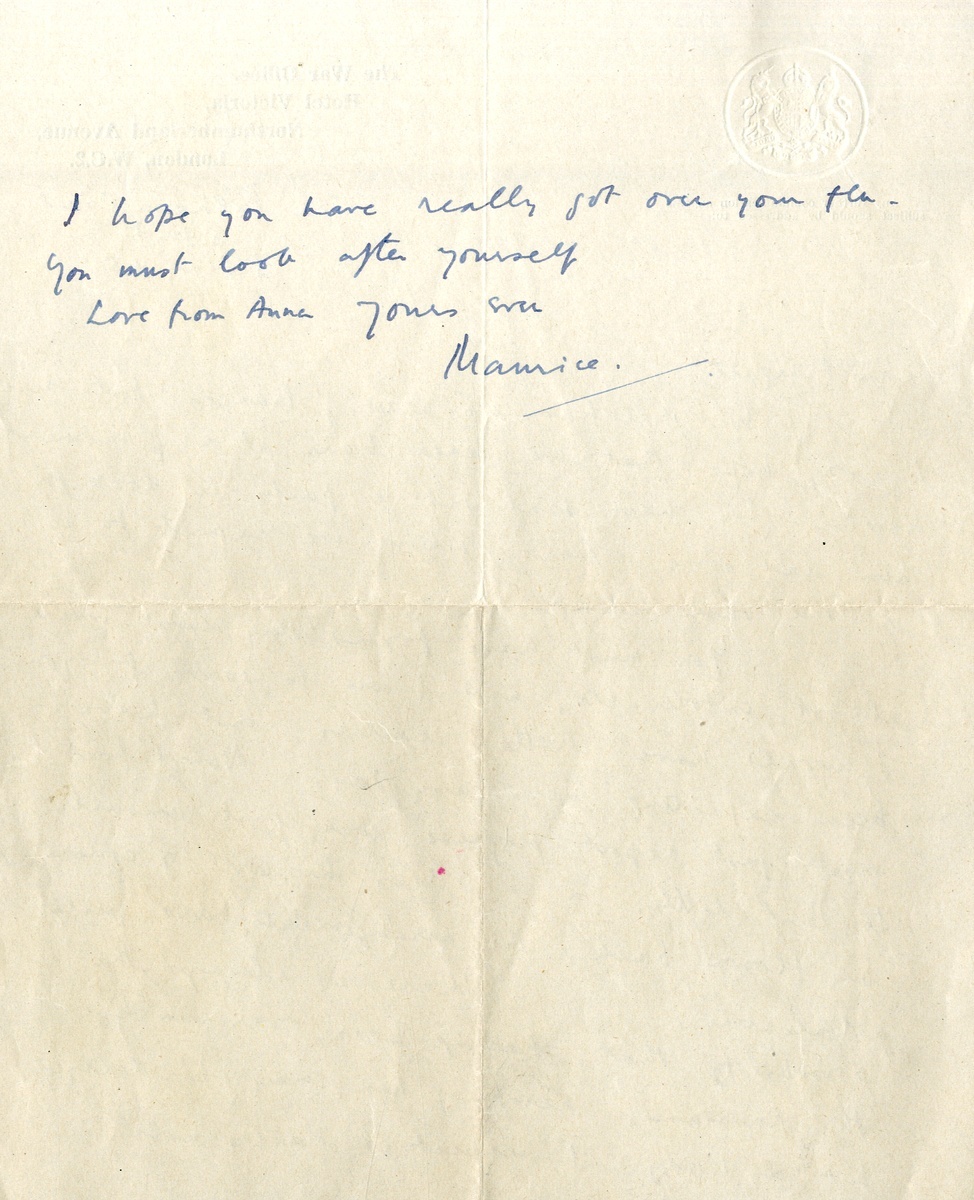

Margaret Suttill still hoped that her husband would be alive and well - indeed a letter of 5 May 1945 from Buckmaster gave false hope, although he was also unaware of Suttill's tragic fate:

'We still have no news of Francis, but there is every hope that we shall hear at any moment now. We have sent out a party to look for him and some others whom we expect to be in the same Camp.

You must have found this last week almost intolerable and I am so sorry for you. I would have written earlier, but have been expecting news any day. Now I feel I must just report progress, even if it amounts to but little.

Yes, he will of course be flown back; arrangements are quite admirable. There is always the possibility that, having been over-run by the Russians, news of him may be delayed, but, as I say, I expect it daily now.

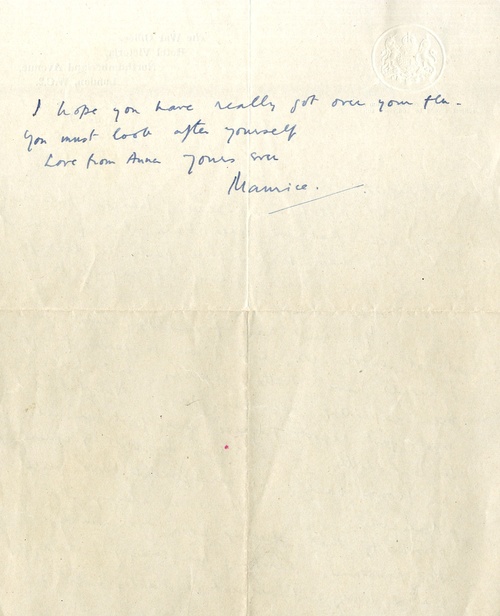

I hope you have really got over your flu. You must look after yourself. Love from Anna, Yours ever, Maurice.'

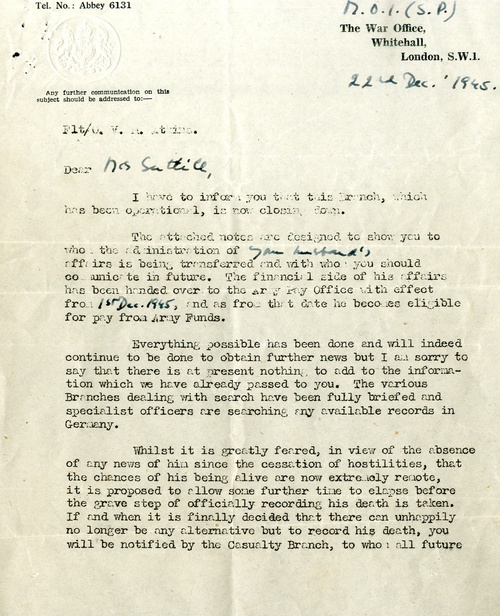

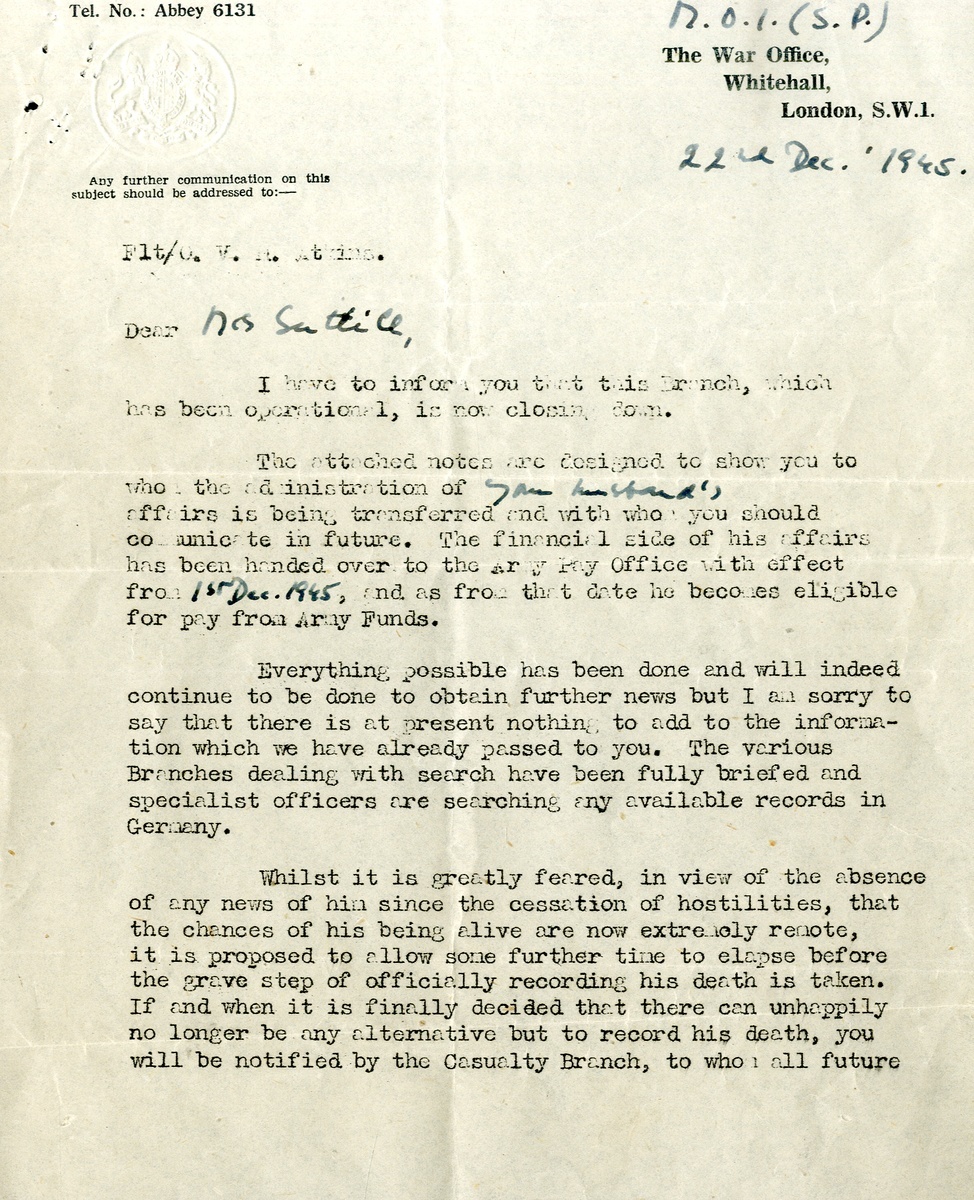

It was false hope, with a letter signed by Vera Atkins, dated 22 December 1945, that states:

'Whilst it is greatly feared, in view of the absence of any news of him since the cessation of hostilities, that the chances of his being alive now are extremely remote.'

PLACES OF COMMEMORATION

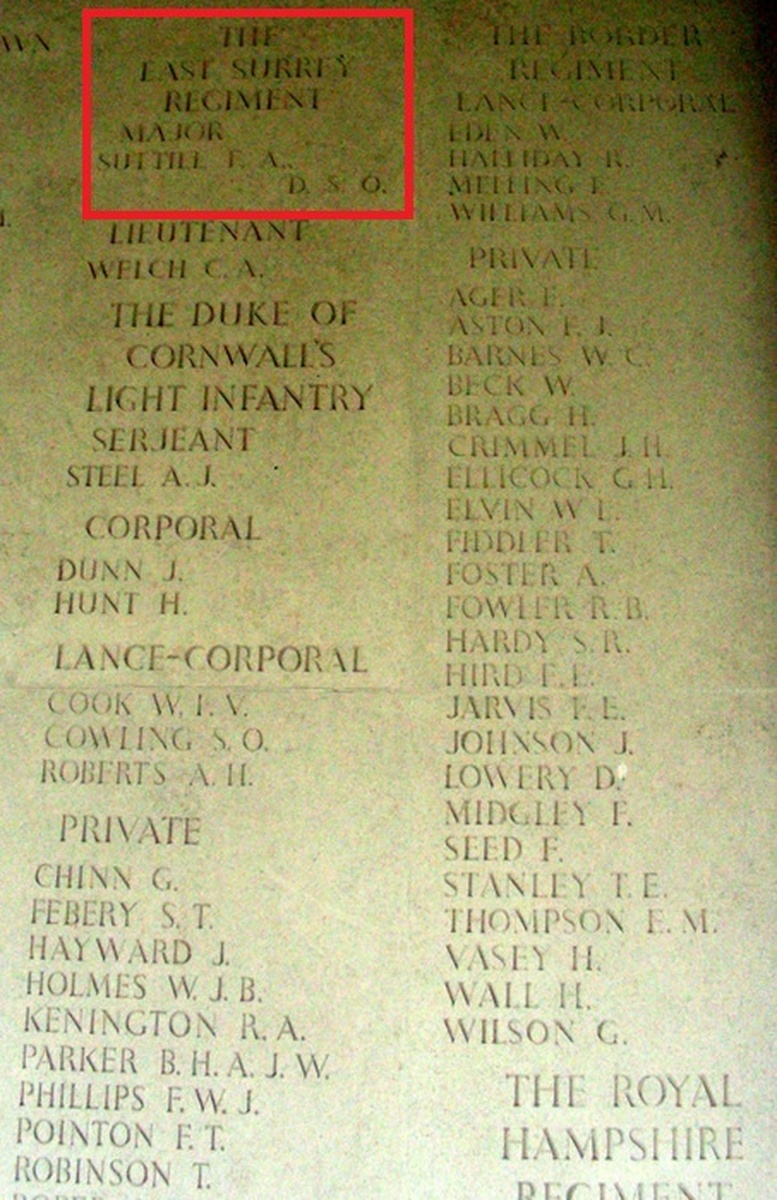

Officially recorded on the Commonwealth War Graves Commission Memorial, Groesbeek, Netherlands.

The S.O.E. Memorial on the Albert Embankment, opposite Lambeth Palace, London, which is surmounted by a bronze bust of Violette Szabo; sculpted by Karen Newman, it was unveiled in 2008.

Roll of Honour on the Valençay S.O.E. Memorial, Valençay.

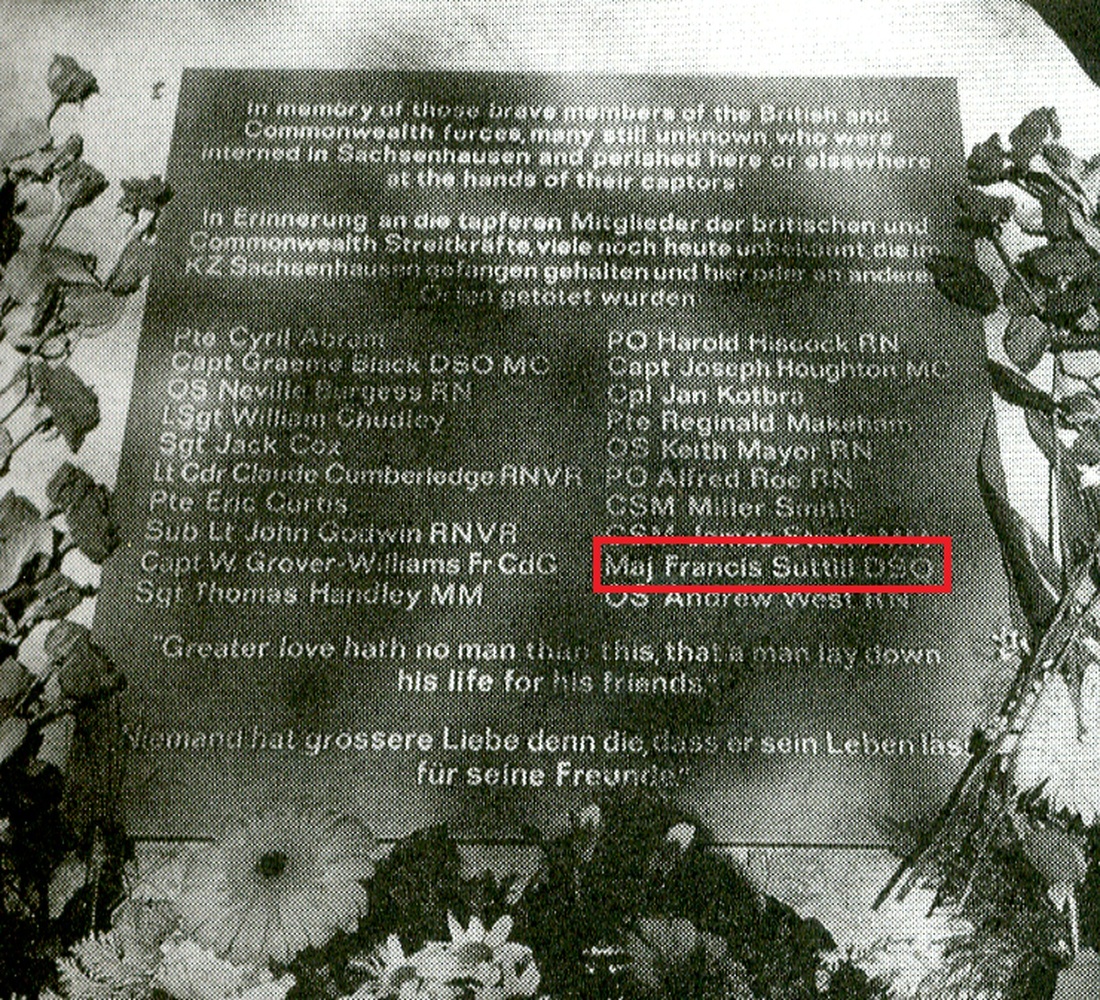

Sachsenhausen Memorial, Germany, at which a wreath is laid each year by Members of the Royal British Legion, Berlin.

Lincoln's Inn 1939-45 Memorial, London.

Stonyhurst College Roll of Honour.

Reference Sources:

Prosper - Major Suttill's French Resistance Network, Francis J. Suttill (2018)

They Fought Alone, Maurice Buckmaster (1958)

Specially Employed, Maurice Buckmaster (1952)

Prosper, Chamber's Journal, Maurice Buckmaster (1947)

Spy Princess, Shrabani Basu (2006)

Agents by Moonlight, Freddie Clark (1999)

A Life in Secrets, The Story of Vera Atkins, Sarah Helm (2005)

S.O.E. in France, Michael Foot (1968)

SS-Major Horst Kopkow, Stephen Tyas (2017)

The Grand Prix Saboteurs, Joe Saward (2006)

No Cloak, No Dagger, Benjamin Cowburn (1960)

The Heroines of S.O.E., Beryl Escott (2010)

Mission France, Kate Vigurs (2021)

Lonely Courage, Rick Stroud (2017)

We Landed by Moonlight, Hugh Verity (1995)

All the King's Men, Robert Marshall (1988)

Moonless Night, Bertram 'Jimmy' James (1983)

Subject to 20% VAT on Buyer’s Premium. For more information please view Terms and Conditions for Buyers.

Sold for

£45,000