Auction: 22003 - Orders, Decorations and Medals

Lot: 487

(x) An outstanding Second War Evader's D.F.M. group of five to awarded to Flight Sergeant (Wireless Operator) P. Jezzard, 622 Squadron, Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve, who served in Stirlings and Lancasters, who was decorated after having returned to action less than six months following a most gallant successful 'Home Run' along the Comet Line after being shot down on his 5th Operational Sortie to Stuttgart; having also earned membership of the Caterpillar Club on that occasion, Jezzard went on to complete a full second tour of Ops before War's end; he was to be tragically killed in a flying accident over the North Sea in April 1948

Distinguished Flying Medal, G.VI.R. (1501713 F/Sgt. P. Jezzard R.A.F.); 1939-1945 Star; Air Crew Europe Star, clasp, France and Germany; Defence and War Medals 1939-45, generally very fine (5)

D.F.M. London Gazette 2 January 1945. The original Recommendation, dated 12 November 1944, states

'This N.C.O. is now nearing completion of his first tour of operations throughout which his skill, courage and devotion to duty have been outstanding. On the night of 15-16 March 1944, the aircraft in which he was despatched on an operational mission to Stuttgart was so severely damaged by enemy action that the crew was ordered to bail out. Before abandoning the aircraft, however, he successfully transmitted a distress message to Base. From this ordeal, Flight Sergeant Jezzard made a successful escape from enemy occupied territory and on return to this country he immediately applied to be returned to his squadron for operational duty. Since his return in August, 1944, he has operated against many heavily defended German targets and has successfully completed several important mining missions. His resourcefulness in emergency and his determination and disregard of personal safety in face of danger is an inspiration to all and is worthy of recognition I strongly recommend an award of the Distinguished Flying Medal.'

Peter Jezzard - or Pete to his friends and comrades - was a native of Prestwich, Manchester and served as a Cadet, No. 183 (1st Prestwich) Squadron A.T.C., prior to Second War service with the Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve. Posted for training to No. 2 Radio School, Yatesbury, April 1943 and thence to 26 O.T.U., he undertook a conversion course on Stirlings at 1665 Conversion Unit before being posted for operational flying as Wireless Operator to No. 622 Squadron (Stirlings and Lancasters) at Mildenhall in November 1943.

He initially carried out eight 'Ops' with the Squadron, including trips to the Frisian Isles, Bayonne and his fourth Op being a first visit to 'The Big City' - Berlin - at the height of the Battle of Berlin on 20 January 1944. That night some 495 Lancasters, 264 Halifaxes and 10 Mosquitos, with 769 aircraft in total, rounded on the city. Thence a trip to Schweinfurt was cut short on 24 February, due to a coolant leak and onto Augsburg on 29 February 1944. The Log Book refers 'Combat with Ju 88. Searchlights and Flak'. He would fly twice on Stuttgart in March, including that fateful flight of 15 March, when in Lancaster I LL828 JI-J piloted by Flight Sergeant P.A. Thompson:

'Take off 1720 Mildenhall. Last heard on W/T at 0141 transmitting "Baling Out". Reports from the crew tell of attacks from night-fighters and from a fix taken of the wireless message it is likely the engagement took place SE of Rouen in France' (Royal Air Force Bomber Command Losses of the Second World War refers).

Of the crew of seven, four (including Jezzard) managed to evade capture whilst the remaining members were taken Prisoner of War; Sergeant T.J. Maxwell, one of those to evade capture, gives the following account:

'The thing about bailing out, in total darkness at night, from a crippled aircraft or splashing your 25 ton Lancaster into a raging sea swell was that you didn't get any practice lessons beforehand, so it was a bit of a new thing. The nearest one got was about a year before was jumping off the top diving board in the warm water and brightly lit baths in Brighton in a flying suit and Mae West.

Then the water had loads of noisy laughter and PT life-saving instructors to help if one got into difficulty.

It was 1.30 in the morning and pitch black, the top board was about 8,000 feet vibrating and descending rapidly, and spewing fuel and oil from ruptured tanks. No friendly life-savers etc, but the reality that our fuel was being exhausted even faster than calculated had now replaced the 'ditching' idea and bailing-out (and pretty soon at that) was the only option left. We, or certainly I was already well into a personal life saving preservation situation.

I was personally totally disenchanted when the channel rowing exercise in total darkness was muted [sic] as a possibility.

I never found the idea of hitting the English Channel at 100mph in total darkness, with sea and swell conditions unknown, and with an indeterminate amount of fuel, to be in the least appealing... Six of the crew all landed in an area 40 miles North East of Rouen and all reasonably close, within a kilometre or so of each other, but when they left the aircraft I was already on the way down some 20 kilometres further back, representing several minutes. The reason for their delay will never be known, but after 57 years almost to the day it has been established that the aeroplane crashed within a couple of miles from where some of the crew were taken POW.

Of the four who returned to England on May 22nd on a DC3 from Gibraltar to Bristol (Whitchurch) I only met up later with Peter Jezzard. Both of us returned to operational flying with our original Squadron 622, Peter finishing his 'tour' in November 1944 on 35 'trips' and myself on 32, finishing on New Year's Day 1945.' (Interview carried out in 2002, refers).

Another member of the crew, Sergeant F. Harmsworth, gives the following account from the time after the crew had landed:

'Later I met a schoolteacher who got me a change of clothes and temporary, false ID papers. He took me to a small rail station and there I bumped into my Wireless Operator Peter Jezzard. With barely a wink of recognition, we were on the train; the Frenchman [Maquis] up front, Pete in the middle, and me at the back of the coach. The train was strafed en-route by the R.A.F. guns so we hopped off the train and headed for a ditch. Later, we hopped back on the train and carried on to Paris. We got to the train station and it was very crowded with local Parisians, plus hundreds of German troops. We left the station and kept the same order of 20 ft. apart. After an hour we arrived at an apartment block and met the teacher's cousin, a vivacious, 20 year old girl, Madeline Vuillemont, who lived with her parents... I was moved across Paris on the metro to the East End... A couple of days after I arrived, trusty John took me to a large store in town, where I stood in line with locals and stood next to German soldiers to get my picture taken in a booth...After 2 days, with good police connections, I received back my French I.D. card with other documents all duly signed and rubber-stamped...They found out it was my 20th birthday, so one night, a sign was put on the door that said, "closed for a family party." I got lots of little presents like toothbrushes, a box of Belgian tobacco and some Galoise cigarettes. Then Peter, the Wireless Operator, was brought in so we got a bit boozed up. Lots of the Cafe patrons were "in the know" - no names were used except nicknames. It was one hell of a night!

Soon I had to say goodbye to these wonderful people. Helen, the Red Cross nurse took me to the main train station and put me on a train heading south. I pretended to be a wounded deaf/dumb ex French P.O.W. On the train, I met Peter again. We met a couple of young Frenchmen who worked at the Post Office...They had a backpack full of stamps that they had stolen from the Post Office to trade for money - so they were most helpful on our journey through France. Our I.D. cards passed muster several times on the way with Gestapo inspectors. We left the main line trains and road in a succession of goods and ammo trains jumping on and off while going uphill! Knees were scarred somewhat!

We came to the Bayonne area and walked through the outskirts. There was a curfew of 10pm so we got a second story room in a flea bag hotel. The Gestapo checked the registers every night, so a special knock was agreed upon for the friendlies - otherwise get out quick.

Early one morning, it was still dark, when we got the wrong knock. We leaped out of the upstairs window in a flash and went running and scrambling through fences, backyards, and garden allotments. Dogs were barking and people were shouting. It was utter pandemonium. I was scared. We ended up in the Railway Yards...After hiding quietly for a couple of hours, we saw a train getting steam up, so the young Frenchmen spoke to the Engineer, who took us to a box car, then moved the train off quickly. During the night we were wakened by the slamming of doors - lots of shouting and "Achtung" and loud guttural German troops. It was an ammunition train being loaded! We fortunately did not get discovered and were very glad to leave.

Next day, we jumped off the train onto a gravel shoulder as it slowed for a hill in the Pyrenees Foothills - scarring our hands, knees and shins in the process. Walking through a village, we entered a forest and stayed in the bush for a couple of days. We were cold and in the open...One of the Frenchmen negotiated with a local Gasogena Taxi to take us to the edge of the Pyrenees Mountains. The taxi had a large wood boiler on the back which burned wood to make it go. We were approaching a checkpoint with a swing down wooden barricade right on top of a steep hill. The taxi started balking. As we stuffed wood in to stoke the fire, we were pushed up the hill. Fortunately, the taxi picked up speed, where it levelled off. Crashing through the barrier, we were chased by cavalry guards on horses - just like a Yankee movie. We descended quickly down hill for about 10 miles, so left them behind. Several more villages beyond, we switched to bicycles and walking on the steep, mountain roads - 5 people on 2 bikes.

A couple of days later, we arranged with a Basque guide to take us above the Snow Line up through the high Pyrenees (away from the roads and the Germans). We slept in shepherd caves by day, and walked by night and managed to avoid German Patrols...We were tracked by dogs and shot at in a long ravine. Eventually we hit the Spanish border.'

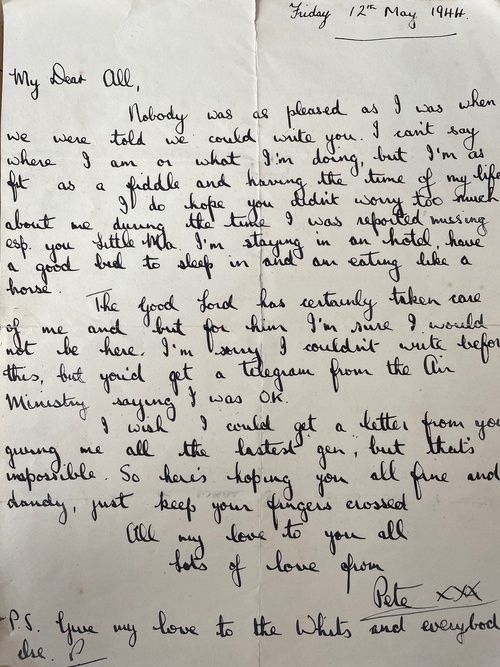

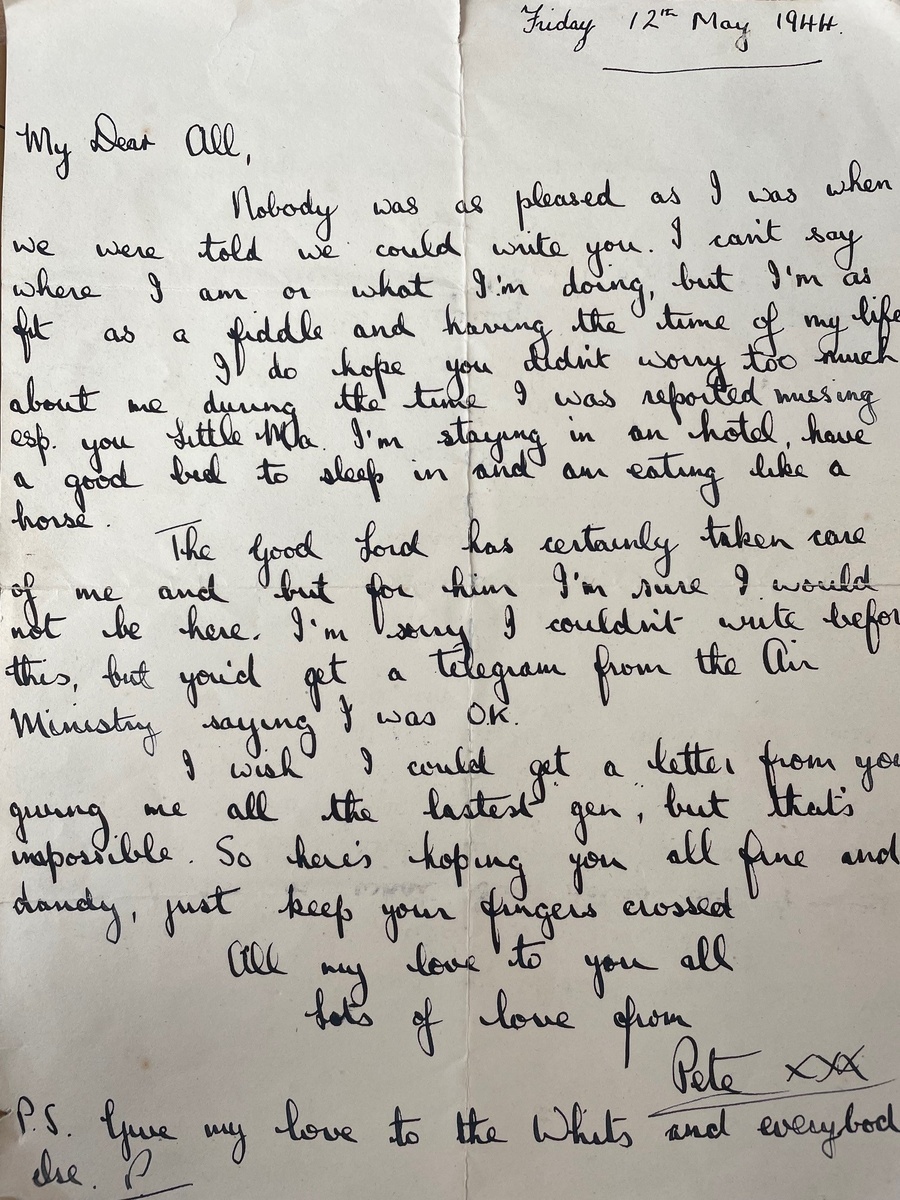

Once in Spain Jezzard and Harmsworth were arrested by the Police, questioned and then transferred to the British Embassy in Madrid. Jezzard was able to write to his family on 12 May:

'Nobody was as pleased as I was when we were told we could write you. I can't say where I am or what I'm doing but I'm as fit as a fiddle and having the time of my life. I do hope you didn't worry too much about me during the time I was reported missing esp. you little Ma.'

Having travelled to Gibraltar, he made it home on 22 May 1944 and asked to be returned to his old Squadron for operational flying.

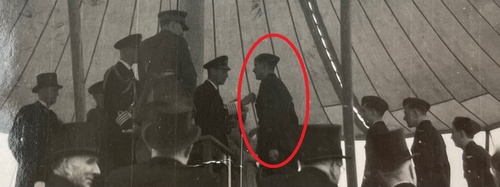

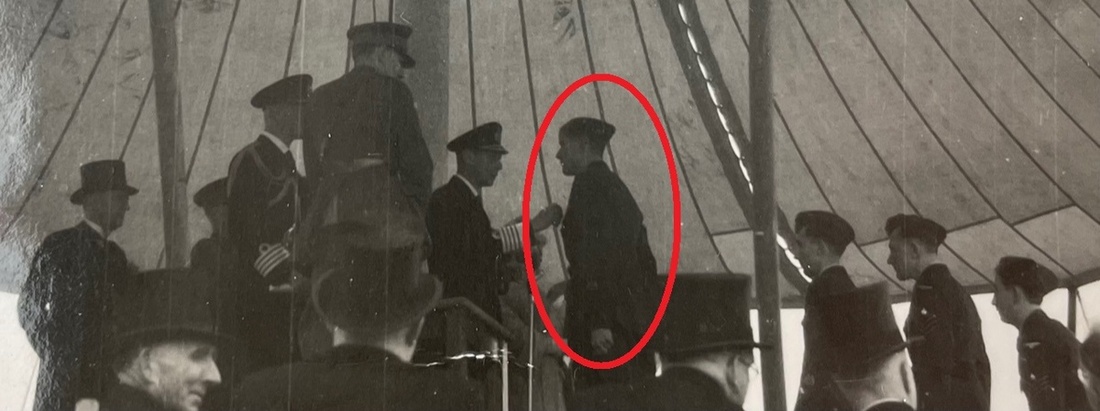

That request was duly confirmed and having arrived at Mildenhall on 1 August 1944, he was on an Op to Bordeaux just four days later. Flying with 'B' Flight he undertook a further 29 operational sorties with No. 622 Squadron, including to Foret de Lucheux, Fort D'Englos, Lens, Brunswick, Hamel, Stettin (2), Eindhoven, Le Havre (2), Rostock Bay, Kiel, Calais (2), Rhur, Cap Gris Nez, Saarbrucken, Dortmund, Kleve, Bonn, Essen (3), Cologne (2), Solingen (2), Koblenz and Oslo Fjord. Having completed his second tour Jezzard was posted as an Instructor to R.A.F. Jurby, Isle of Man, January 1945, where he was invested by The King with his Medal.

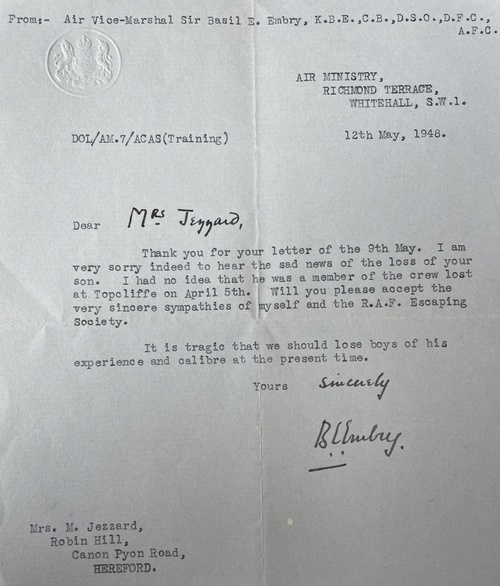

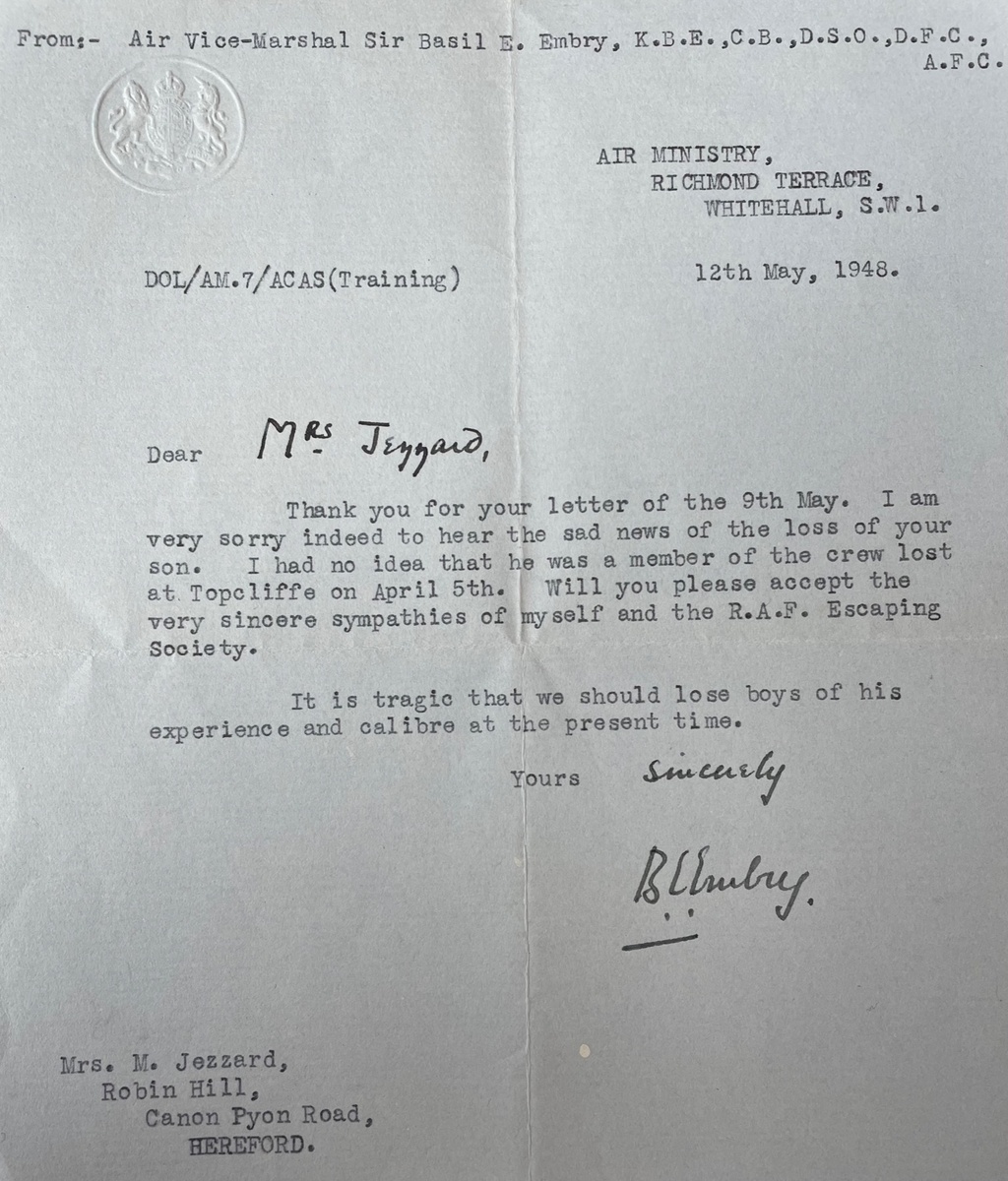

Posted to 1 A.N.S. R.A.F. Topcliffe, North Yorkshire in March 1947, Jezzard was killed when his Wellington crashed into the North Sea whilst on a Navigation Exercise on 5 April 1948. He is commemorated on the Armed Forces Memorial, Staffordshire and Air Vice-Marshal Sir Basil Embry, President of the RAF Escaping Society wrote to mother:

'I am very sorry indeed to hear the sad news of the loss of your son...It is tragic that we should lose boys of his experience and calibre at the present time.'

Sold together with the following archive of original material:

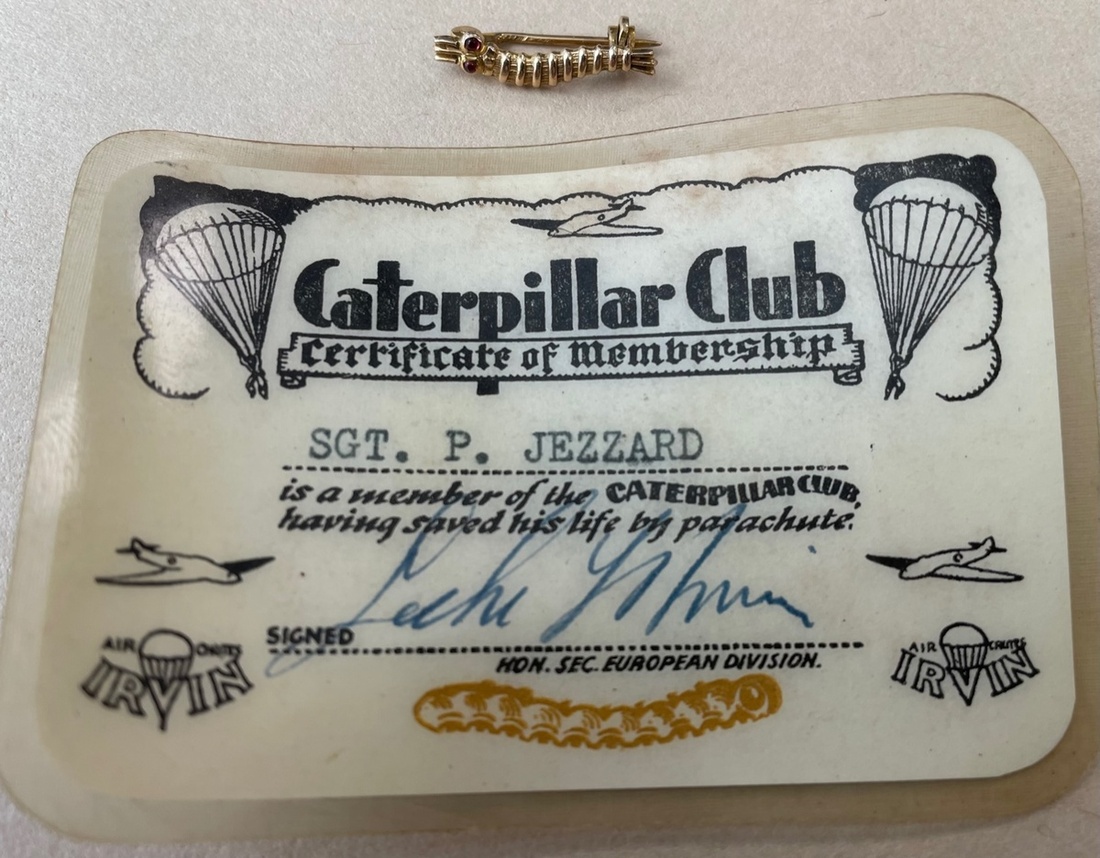

(i)

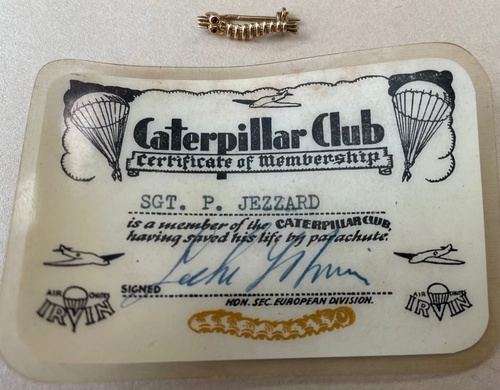

Caterpillar Club gold brooch Badge, with 'ruby' eyes, reverse engraved, 'Sgt. P. Jezzard', in Irving box, with named Membership Card, and enclosure letter, dated 21 July 1944

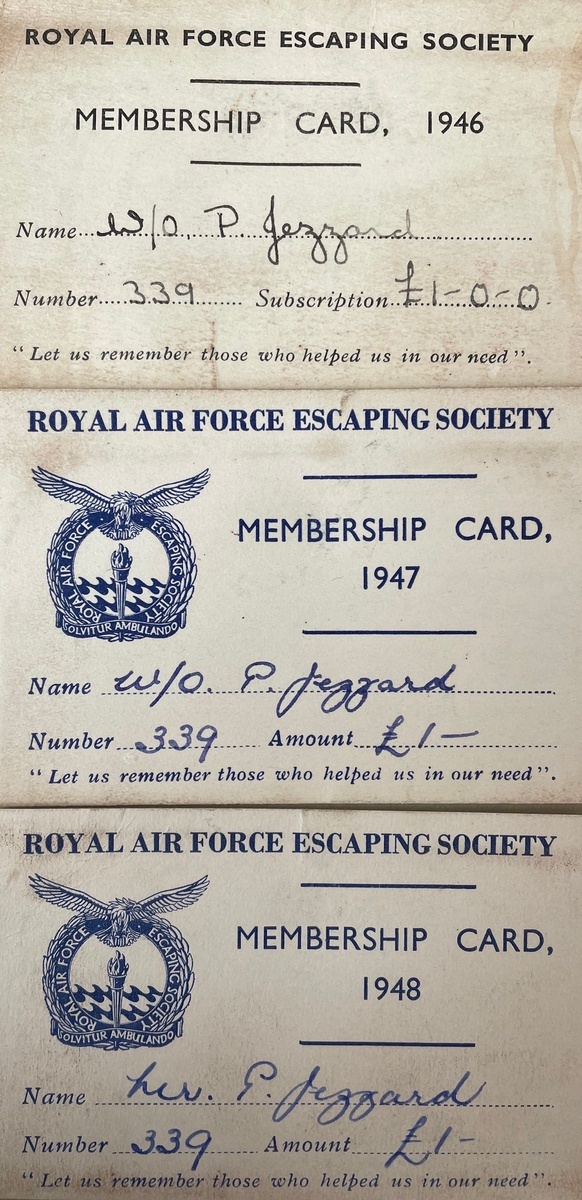

(ii)

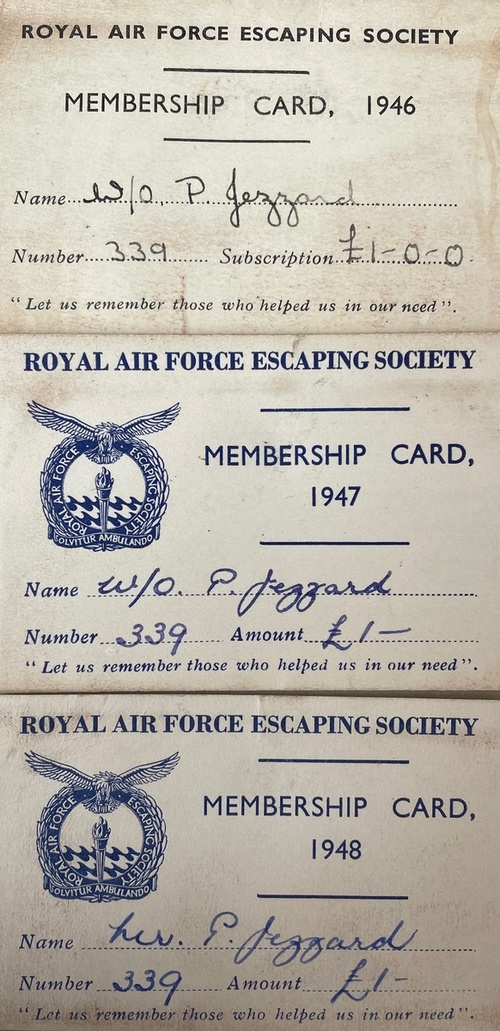

His 'Escapers' Compass, two Silk Maps of France, Royal Air Force Escaping Society Badge, together with three Membership Cards for the years 1946-48

(iii)

Cloth insignia, including WAG Brevet.

(iv)

R.A.F. Navigator's, Air Bomber's and Air Gunner's Flying Log Book (15 April 1943-5 April 1948), stamped 'Death Presumed, Central Depository, Royal Air Force'.

(v)

Letter from recipient to his family, written after he had escaped to Spain from Occupied France, dated 12 May 1944.

(vi)

Congratulatory Telegram from Air Chief Marshal A.T. "Bomber" Harris, on the occasion of the award of Jezzard's D.F.M., dated 23 November 1944 and Telegram to the same effect from the Officer Commanding No. 622 Squadron.

(vii)

Telegram to recipient's father informing him that his son is 'missing' whilst on a training exercise, dated 6 April 1948 and Air Ministry letter to recipient's father stating that Death is Presumed, dated 17 June 1948.

(viii)

Letter of Condolence to recipient's mother from Air Vice-Marshal Sir Basil Embry, dated 12 May 1948.

(ix)

Several photographs of recipient, including a portrait photograph in uniform; newspaper cuttings and other ephemera.

Subject to 5% tax on Hammer Price in addition to 20% VAT on Buyer’s Premium.

Sold for

£5,000

Starting price

£2700