Auction: 22003 - Orders, Decorations and Medals

Lot: 440

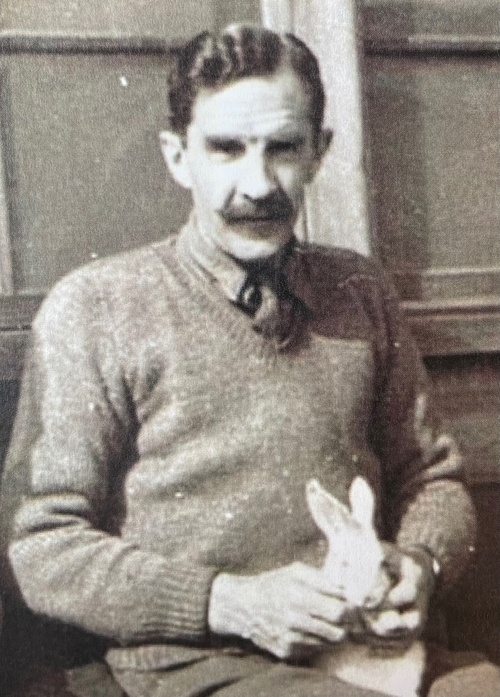

A superb 'Fall of Malaya' D.S.O., Second World War Prisoner of War Camp Leader's O.B.E., 'Battle of Cambrai 1918' M.C. group of nine awarded to Brigadier M. Elrington, Loyal North Lancashire Regiment

Distinguished Service Order, G.VI.R., the reverse of the suspension bar officially dated '1945'; The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire, Military Division, 2nd Type, Officer's (O.B.E.) breast Badge, silver-gilt; Military Cross, G.V.R., unnamed as issued; British War and Victory Medals (Capt. M. Elrington.); 1939-45 Star; Pacific Star; Defence and War Medals 1939-45, mounted court-style as worn, good very fine (9)

Ex-Spink Numismatic Circular.

D.S.O. London Gazette 13 December 1945. The original Recommendation by Lieutenant-General Percival states:

'Throughout the operations in Johore and Singapore in January and February of 1942 this Officer commanded his Battalion with outstanding calmness, courage and judgement.

He remained imperturbable in many difficult and awkward situations from which he extricated his unit with skill and resources. In the latter stages of the fighting in Singapore, he inspired those under him by his gallant conduct under fire and contributed largely to the successful defence which prevented hostile penetration into the area.'

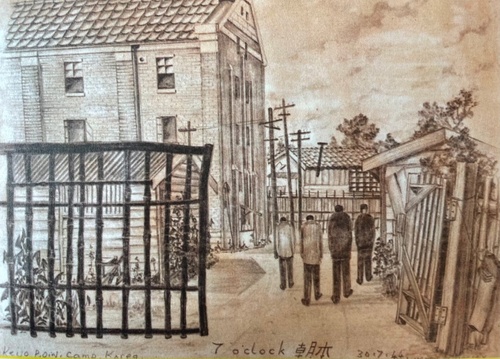

O.B.E. London Gazette 12 September 1946. An award for Services as a Prisoner of War, the Recommendation - for his work as Camp Leader at Keijo Camp, Korea, from 25 September 1942-9 September 1945 - states:

'The firmness, dignity and tact of this officer in dealing with the Japanese authorities in Korea, where he was Senior British Officer in a Prisoner of War Camp, contributed greatly to the well-being and morale of all his fellow prisoners. His ability to sum up the psychology of his captors made it possible for him to extort many concessions which made life tolerable.'

M.C. London Gazette 10 December 1919. An award for the actions at the Battle of Cambrai on 13 October 1918, when he assumed Command of the Battalion after the Commanding Officer and all the Company Commanders had been killed:

'When the advance was checked and there was some doubt as to the exact line held, he made a most daring reconnaissance along the whole length of the Battalion front and established connections with units at a time when any movement drew considerable machine-gun fire at close range.'

Mordaunt Elrington was born on 28 December 1897 and it seems forever written in the stars that he should succeed to the Command of the Battalion of the Loyal North Lancashire, for his ancestor, General Sir John Mordaunt - after whom he was named - raised the 47th Foot in 1741. Furthermore, his grandfather and uncles had also served in the Loyal North Lancashire Regiment.

Great War - first 'gong'

Upon the outbreak of the Great War, Elrington had been at Oxford reading Medicine but soon went up to Sandhurst and thence was commissioned into the Loyal North Lancashire Regiment. He served in France with the 1st and 3rd Battalions from January 1917 and also served as Adjutant to the 4th Battalion, York & Lancaster Regiment. It was indeed with that unit that he won his first laurels during the Battle of Cambrai in October 1918.

Inter-War; Turkey & China

Remaining with the York & Lancaster Regiment until 1920, he transferred back to the 1st Battalion, Loyal North Lancashire Regiment, who were at that time stationed on Malta. They were called up to form part of the Allied Army of Occupation in Turkey and landed at Scutari on 15 December 1921. One engagement was recalled by Elrington:

'Our chief job was keeping order in Anatolia, where the Sultan's Army had been disbanded, never been paid, and had turned bandit. Kemal, the Attaturk, routed the Greeks at Smyrna and his forces were moving to take Constantinople. I was told to stop them. We had 30 to 35 Infantry men mounted on mules and ponies and I knew we couldn't stop them with this small force. I really didn't know what to do.

But, I had a beautiful mare, a polo pony, and I took my standard-bearer with me and simply sat on my horse on the bridge over the first river the Kemalists would have to cross. I saw the Army approaching in a cloud of dust. When an Officer arrived we saluted and I told him he couldn't advance because if he did he would meet our cavalry - my men were out of sight and he hadn't a clue how many we really were. The bluff worked and I stayed on the bridge until nightfall when Allied reinforcements finally arrived.'

Remaining with the 1st Battalion, they were posted to China in 1923 and were variously stationed at Wei-hai-Wei, Tiensin and in Shantung, Northern China. Again, he recalls:

'All the major powers had concessions in China and we provided security for the nationals, kept communications open to the sea, and guarded embassies in the chaos when the warlords were fighting for control of Peking.'

After a stint in India, Elrington was transferred to the 2nd Battalion and thence went home in order to take up the post of Staff Captain to Brigadier-General Wavell. He saw some four years in the War Office, being promoted Major and thence returning to the 2nd Battalion in 1938.

Second World War - destiny fulfilled

During 1939, as the situation in Europe continued to descend towards impending World War, his Battalion were sent off to Singapore under the Command of Lieutenant-Colonel G. G. R. Williams. Elrington was his trusty Second-in-Command.

With the help of 250 coolies, they crossed Keppel Harbour to Blaking Mati in order to dig trenches and put down wire to protect the other side of Singapore Island. By December they were posted to Kuala Lumpur and also onto Telop Paku for further specialist training. With the Fall of France and the understanding that a War in the East would soon follow, planning continued apace. The Forces in the region were split into two Malaya Infantry Brigades, the 2nd Battalion formed part of the 1st Brigade in September 1939, along with the 1st Battalion, Manchester Regiment and 2nd Battalion, Gordon Highlanders. Just two weeks later Williams was made Brigadier and handed the Command of the Singapore Infantry Brigade. Thus, just shy of two centuries after Sir John Mordaunt had raised the unit, Elrington assumed Command and was made Lieutenant-Colonel in December 1940. The 1st Battalion, Malaya Regiment and 17th Battalion, Dogra Regiment joined the Brigade that same month.

As 1941 dawned, intensive training of all units in order to prepare for the impending Battle they faced was the single focus. By July 1941, the Japanese occupied Southern Indo-China and were less than 300 miles from the city.

Together with the Manchesters, his unit were stationed to defend the Keppel Sector and when the full force of the enemy came to bear, they overran the northern section of Malaya within a month. Lieutenant-General Percival - whose name shall come forth later - called upon the 2nd Battalion to move up to Segamat in order to attempt to reinforce the 9th Indian Division. They reached Segamat on 13 January and were straight into the action. Elrington commented later:

'We went up country and then fought down the Malay Peninsula until we ran out of land. In Singapore came the order to fight to the last man and the last bullet. I shook hands with the officers and got on with it.'

That final Battle for the fate of Singapore began on 30 January 1942, being ordered to defend the Johore causeway. Having permitted as many retreating men cross throughout the night, they blew the causeway. Singapore was now an isolated fortress. His unit traversed Keppel Harbour to Blaking Matif and he took on the command of Coastal Artillery and machine-gunners from the Federated Malay States Volunteer Force.

Battle of Pasir Panjang

The final days of action within Singapore will forever remain engrained in the history of the Second World War. Elrington was in Command of the 2nd Battalion throughout. During the night of 12 February the north and east coasts of Singapore Island were evacuated and the main body of the Allied force withdrew to the centre. The next morning did not begin well for the unit, as whilst ordering 'B' Company to withdraw through the Gap crossroads, a party of Indian Sappers mistook them for the enemy and began firing upon them - which assisted the enemy who were also directing fire on them.

The unit regrouped and they marched along the Ayer Road, passing in single file through the burning remains of the Notmanton Oil Depot at Gillman Barracks. By Valentine's Day, they were under attack from dive bombers and accurate artillery fire which caused huge casualties amongst the gallant band which remained of the 2nd Loyals. Whilst this went on 'B' Company repulsed the enemy in front of the bungalow on the Ayer Road but the Alexandra Military Hospital fell to the enemy. Nurses and patients alike were bayoneted and shot - including the infirm.

15 February was the final day of resistance which was possible against the hordes who were now surrounding the survivors. It seems possible that men of his unit fired the final shots of the Defence of Singapore when at approximately 1930hrs 'A' Company opened up on some Japanese who showed themselves on the high ground above the Barracks. Just an hour later the Surrender was actioned. Elrington and his men withdrew to Marlborough Camp and sent the following message:

'I congratulate you on fighting so well. Through no fault of your own you have been ordered to surrender. Remember the lads who have fought and died, and show the same spirit of duty and discipline in defeat.

Do nothing to bring discredit on the Loyals as Prisoners of War.

God bless you.'

In the bag

Having inspired his men throughout the campaign in Malaya and Singapore, Elrington was duly awarded the D.S.O., an award which was promulgated after the end of the War. He arrived at Changi Camp on 17 February and remained there until 15 August 1942. That Camp was lead by Lieutenant-General Percival and Elrington's detachment was led by Major-General K. Simmons. He was thence transported to Korea and Keijo Camp, near Seoul, Korea, of which he was Camp Leader throughout his time there, 25 September 1942-9 September 1945.

The scenes and treatment at the Camp were dreadful. Although it was used by the enemy as a 'show' Camp, it was far from an easy assignment. As recalled by Lieutenant Lever:

'Men were now changed so much that they were unrecognisable as the same people they had been before the surrender. Body and soul were often kept together by the rare Red Cross parcel which was deemed infinitely better than the eternal, infernal, rice and stew.'

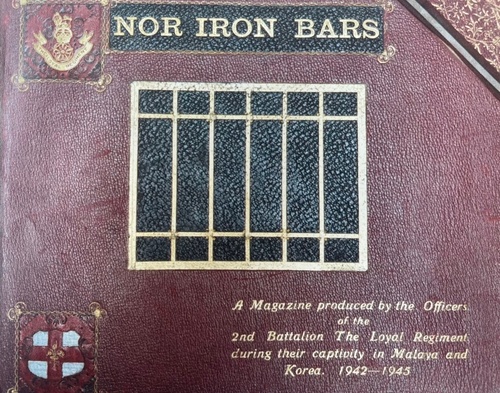

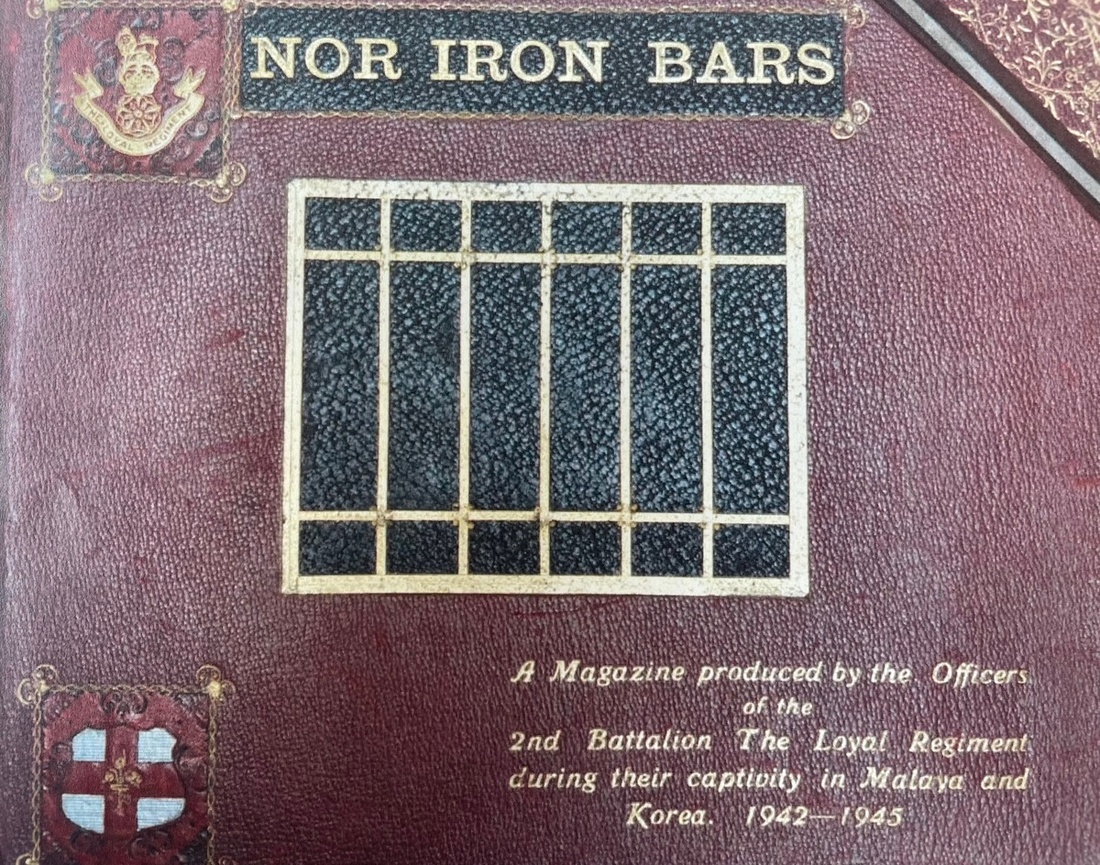

Elrington himself suffered throughout due to a recurring respiratory illness, no doubt the result of the dampened coal dust balls which were burned to heat themselves. The typical spirit of the British Prisoner was evident in their Camp, doing all they could to disrupt the Japanese machinery. The forced labour they were assigned to often included work upon freight trains. The Loyals made it their work to constantly alter the labels and thieve whenever possible. They also set about publishing their own magazine - Nor Iron Bars - copies of which have survived and are maintained with pride in the Regimental Museum to this day. Elrington continues:

' ‘If they were caught with the magazine their punishment would have been terrible. Production of it was punishable by torture and death. These pages were surreptitiously produced, passed from hand to hand and eventually smuggled out of captivity, in spite of the grave risks involved; indeed this constant fear of secrecy added spice to our enjoyment and each successive edition of Nor Iron Bars gave a fresh fillip to our morale.’

As their captivity wore on, the War had begun to turn:

'It will be remembered that after VE Day there was no prospect of an immediate end to the war in the Far East. After the reaction of VE Day our morale ran so high that we chafed as each day went by. But, our captors not only chafed, they trembled. Their paramount fear was not of defeat, or death, but of war with Russia. They had no illusions about the Russians, and no power to stay their advance.’

When freedom finally arrived:

'After the unbelievable news of VJ Day [August 15] had turned to weeks of impatient waiting for deliverance, the great moment for us arrived on the 9th September. Amid tremendous excitement and noise of tanks, trucks, bewildered Japs and frantic soldiery, a very large and confident American Company Commander sort [sic] out our CO, saluted smartly and shouted, “Say, Colonel, who d’ya want shot?”'

Returned home, Elrington completed the obligatory MI9 debrief and made no mention of his own work, instead singling out the efforts of his Adjutant, Captain E. W. Paque who acted as Liaison Officer. The fine efforts of Elrington whilst Camp Leader was formally recognised, with the O.B.E. added to his laurels in the process. It has also been noted that Elrington saw the Japanese making a particular effort to pay particular attention in doling out harsh treatment to the Australians who were in his Camp. This effort was clearly in some vain hope of turning the gallant Diggers against The Crown.

Journey's end

Re-appointed as CO of the 2nd Battalion in May 1946, he was advanced Colonel and went with the Battalion to Europe as part of the Occupation Force in January 1947. Promoted Brigadier, he retired on account of the respiratory issues (suffered whilst in the hands of the Japanese) in August 1950 and worked for Mobil Oil. His health required a drier climate and he moved to Santa Fe, New Mexico and became Assistant-Headmaster at the Santa Fe Prep School in 1966. He died in 1981; sold together with a tape recording with Elrington recalling his service, beside a bound book with various detailed reference sources and extracts, a quantity of copied research, also including images of the recipient.

He also penned With 2nd Loyals in Captivity, published in Lancashire Lad, with his account of the actions available at The National Archives (CAB 106/174). Further details and archives are held by The Queen's Lancashire Regiment Museum, Fulwood Barracks, Preston.

Subject to 20% VAT on Buyer’s Premium. For more information please view Terms and Conditions for Buyers.

Sold for

£11,000

Starting price

£9500