Auction: 22003 - Orders, Decorations and Medals

Lot: 424

'I hope the General is not too disappointed in me?'

So muttered Lieutenant-Colonel Best-Dunkley to the Padre in the Casualty Clearing Station after his gallant stand.

'The padre has given me your message, and I am very much touched by it.

Disappointed? - I should think not, indeed. I am more proud of having you and your Battalion under my Command than anything that has ever happened to me.

It was a magnificent fight, and your Officers and men behaved splendidly, fighting with their heads as with the most superb pluck and determination.

The 31st July should for all time be remembered by your Battalion and Regiment and observed with more reverence even than Minden Day. It was no garden of roses that you fought in. I have heard some of the stories of your Battalion's doings and they are glorious. And I have heard of your doings too, and the close shave that you had.

Nothing would give me greater pleasure than that you should come back and command your Battalion, and I greatly hope you will. I am afraid you have painful wounds, but I trust they will not keep you long laid by.'

The reply from Major-General Jeudwine, who was forced to deliver the following poignant words just a few days later at the funeral of Best-Dunkley:

'We are burying one of Britain's bravest soldiers.'

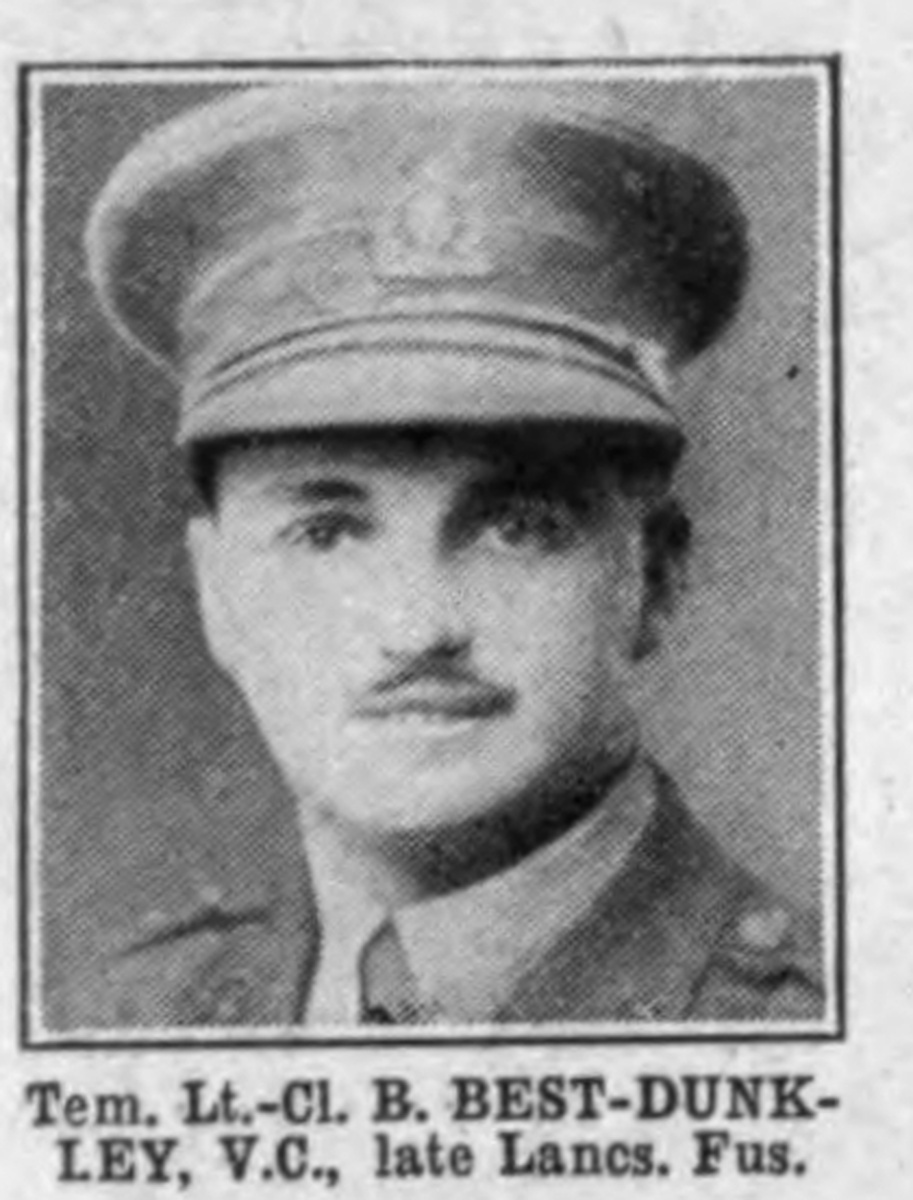

The important posthumous 31 July 1917 'Battle of Passchendaele' Victoria Cross group of four awarded to Lieutenant-Colonel B. Best-Dunkley, 2/5th Battalion, Lancashire Fusiliers

A pre-War militiaman who was out in China working as a Schoolmaster, Best-Dunkley had an adventure across Russia before he was even able to enlist and reclaim his commission

Serving in France during the 1916 Battles, he was left with a '...customary squint and twitch of the nose...this habit as the result of shell-shock on the Somme'; nonetheless he assumed Command of his unit in October 1916 and was duly 'mentioned' for his services in the following months, also surviving the first use of mustard gas

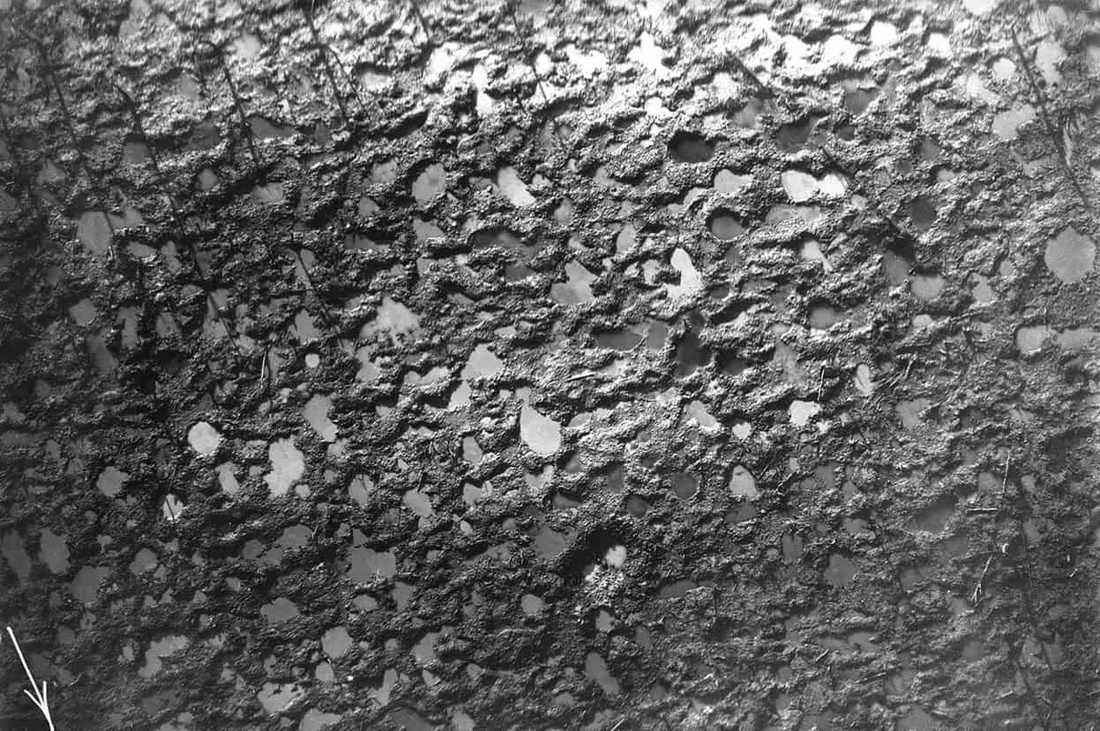

Whilst his character and attitude were sometimes questioned by his comrades, there could be no finer example of his true colours than on the battle-scarred fields of Pilckem Ridge, with trees cut down to stumps, shell-holes filled with water, mud turned to slime and the whole field strewn with the '...mangled remains of men and horses lying all over in a most ghastly fashion'

Early in the attack, Best-Dunkley was seen cooly advancing '...walking stick in his hand, as calmly as if he were walking across a parade ground' but when all the Officers of 'C' Company were cut down, he sprang to action and led the advance himself

As the day drew on and having set up his Battalion HQ in Spree Farm, the unit soon found themselves falling back with the enemy putting in a continued, ferocious counter-attack; he took command of the survivors of his unit and the gallant stragglers who remained from the 1/8th (Liverpool Irish) King's Regiment and stuck it to the enemy - they were to advance no further

Despite having been wounded earlier in the day, Best-Dunkley manned the front trench and gave them hell, simply inspiring all around; up to his waist in water, he would be mortally wounded by a salvo of shells from his own gunners which fell agonisingly short

Days before the Battle he had learned his son had been born and it was to be that they would never meet, Best-Dunkley expired just two days after his twenty-seventh birthday - his V.C. would be pinned onto the shawl of his infant a few months later

Victoria Cross, the reverse of the suspension bar engraved 'Capt. (T/Lt. Col.) B. Best-Dunkley. late Lanc. Fus. attd. 2/5th Lanc. Fus. T.F.', the reverse of the Cross engraved '31. July. 1917.' 1914-15 Star (Lieut. B. Best-Dunkley. Lan. Fus.); British War and Victory Medals, with M.I.D. oak leaves (Lt. Col. B. Best-Dunkley.), all but extremely fine (4)

Provenance:

Kaplan, November 1982.

Chimperie Agencies, August 1984, when understood to have been purchased by Jack Stenabaugh, the well-known Canadian collector.

Purchased Spink, September 1986.

The Lancashire Fusiliers were the single most decorated Regiment during the Great War, earning no less than eighteen awards of the Victoria Cross. For the centenary of the Great War, seventeen of the eighteen were traced and displayed at The Fusilier Museum, Bury. This award was considered to be the 'lost' Lancashire Fusilier Victoria Cross as it was the only award which was not located for display on that occasion.

The Victoria Cross & the Battle of Passchendaele - 31 July 1917

There were thirteen awards of the Victoria Cross and a Bar to the Victoria Cross for actions on 31 July 1917. This remains as one of just two awards not presently in a Museum Collection. The recipients and the locations of the Medals as follows:

[Bar to Victoria Cross]

Captain N. G. Chavasse, Royal Army Medical Corps (31 July-2 August 1917), Lord Ashcroft Collection.

[Victoria Cross]

Captain H. Ackroyd, Royal Army Medical Corps (31 July-1 August 1917), Lord Ashcroft Collection.

Corporal, later Brigadier L. W. Andrew, New Zealand Expeditionary Force, National Army Museum, Waiouru.

Sergeant R. Bye, Welsh Guards, The Guards Regimental Headquarters.

Lieutenant-Colonel, Temporary Brigadier-General C. Coffin, Commanding 25th Infantry Brigade, Royal Engineers Museum.

Captain T. R. Colyer-Fergusson, Northamptonshire Regiment, National Trust Property, Ightham Mote.

Corporal J. M. Davies, Royal Welch Fusiliers, Royal Welch Fusiliers Museum.

Sergeant A. Edwards, Seaforth Highlanders, The Highlanders Museum.

2nd Lieutenant D. G. W. Hewitt, Hampshire Regiment, location unknown.

Lance-Sergeant T. F. Mayson, The King's Own (Royal Lancaster) Regiment, Kings Own Royal Regimental Museum.

Private G. I. McIntosh, Gordon Highlanders, Gordon Highlanders Museum.

Sergeant I. Rees, South Wales Borderers, Regimental Museum of The Royal Welsh.

Private T. Whitham, Coldstream Guards, Townley Hall Art Gallery, Burnley.

V.C. London Gazette 6 September 1917:

'For most conspicuous bravery and devotion to duty when in Command of his Battalion, the leading waves of which, during an attack, became disorganised by reason of rifle and machine gun fire at close range from positions which were believed to be in our hands.

Lieutenant-Colonel Best-Dunkley dashed forward, rallied his leading waves, and personally led them to the assault of these positions, which, despite heavy losses, were carried. He continued to lead his Battalion until all their objectives had been gained. Had it not been for this Officer's gallant and determined action it is doubtful if the left of the brigade would have reached its objectives. Later in the day, when our position was threatened, he collected his Battalion Headquarters, led them to the attack, and beat off the advancing enemy. This gallant Officer has since died of wounds.'

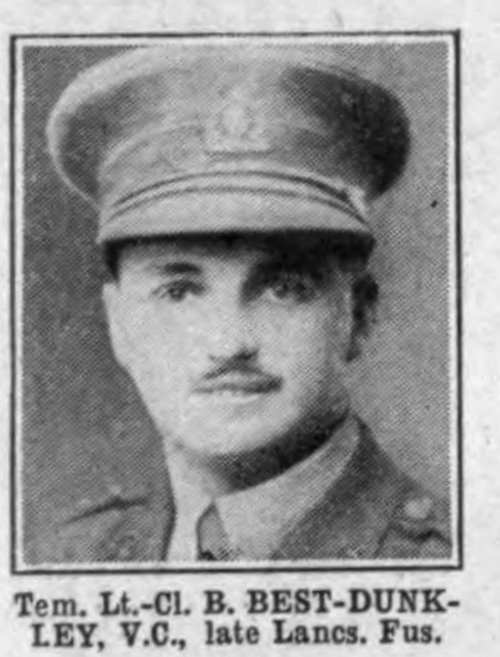

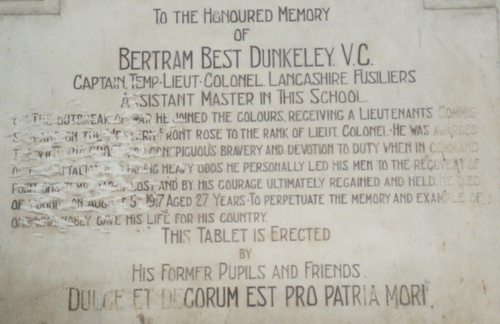

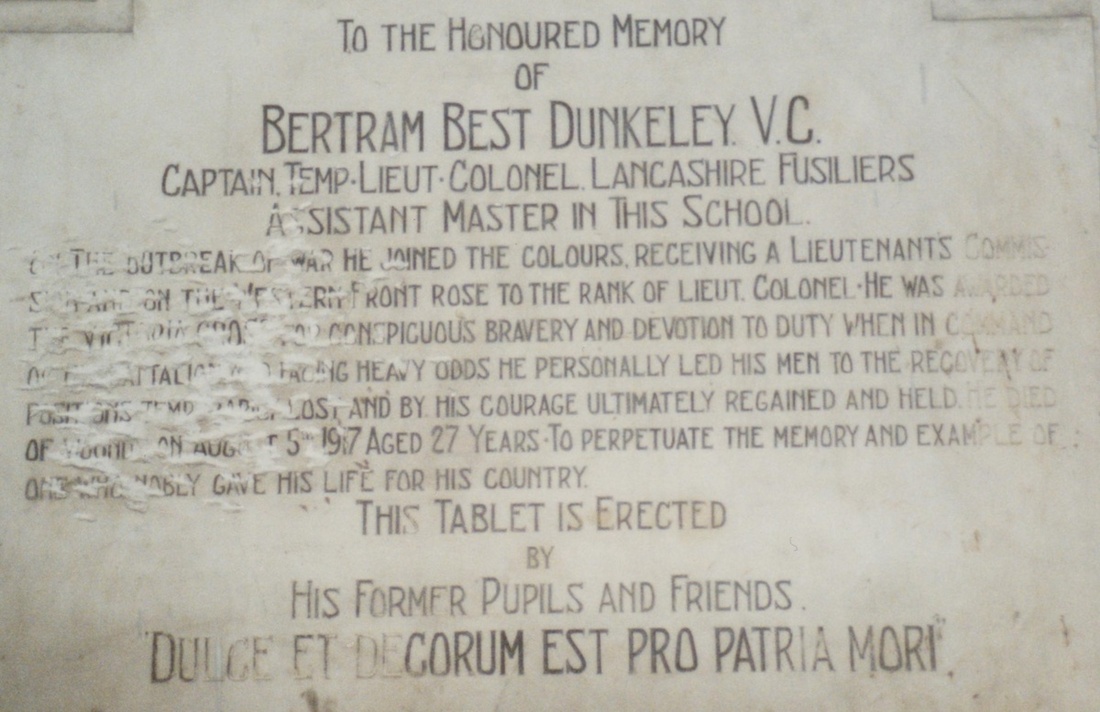

Bertram Best-Dunkley was born at York on 3 August 1890, the son of Alfred Corah Dunkley and his second wife, Augusta. Young Best-Dunkley was educated at a military school in Germany and had worked as a teacher in Ireland. He was first commissioned into 6th Battalion, Lancashire Fusiliers on 1 November 1907 and was promoted Lieutenant on 14 June 1909 and was the Machine Gun Officer. By 1911 he was working as a tutor at Gore Court Prep, Tunstall, Sittingbourne, Kent but his work took him off to China, being offered a contract as Assistant Master at the Tientsin Grammar School.

Great War - early shots

With the outbreak of the Great War, Best-Dunkley was keen to return home in order that he would answer the call to arms. Taking leave from his teaching job in Tientsin, he had an adventurous journey home through Siberia to St Petersburg, onto Stockholm, Christiania and Bergen, finally landing at Newcastle-upon-Tyne.

He was straight back to join the 4th Battalion at Barrow-in-Furness on 13 September 1914, spending the end of that month in hospital for an appendectomy. Transferred to the 2nd Battalion in May 1915, he was later seconded to the King’s Own (Royal Lancaster Regiment) and went over to France in July 1915. He then made home with the 2/5th Battalion, Lancashire Fusiliers, who had been raised at Bury in September 1914.

With them he served as Claims Officer and thence Adjutant. Appointed acting Captain on 6 July 1916, he went through the horrors of the Somme Battles, including the Battles of Guillemont, Guinchy, Flers-Courcelette and Morval. Confirmed Captain, he was to assume command of the Battalion on 20 October and was 'mentioned' for this period (London Gazette 22 May 1917, refers). A fine insight into his character, besides the effects of the actions which he saw, are given in the first-hand account At Ypres with Best-Dunkley, by Thomas Hope Floyd, who served as a Subaltern in his Battalion. He gives some detail into the man, upon seeing him for the first time the following summer:

'I was very interested to see this extraordinary man of whom I had heard so much...He is small, clean-shaven, with a crooked nose and a noticeable blink. He looks harmless enough; but I noticed something about his eyes which did not look exactly pleasant. He looks more than twenty-seven [he was 26 at this time]. When War broke out he was a Lieutenant. It is interesting to note that he was educated at a military school in Germany! (And he had travelled a good deal in the Far East. 'When I was in China' was one of his favourite topics of conversation.) I have not yet spoken to the man, so I am not yet in a position to judge him myself. I will tell you my own opinion of him when I have had a little experience of him. I may just remark that an Officer observed in the mess this morning that he supposed that there were some people who liked the Kaiser, but he was sure that there was not a single soul who liked Best-Dunkley! That is rather strong.'

Best-Dunkley was clearly a hard-working CO who wanted nothing more than success, however the mental strain of the actions which he had previously seen left several to consider him '...a petty tyrant', at the same time as being thought of '...a brilliant young man, endowed with a remarkable personality.'

1917 - gearing up

Now returned to the France after home leave, Floyd gives further first hand account of his time with Best-Dunkley:

'We had a Battalion parade in a large field this morning. There was a long type-written programme of the ceremony to be gone through. We paraded on the company parade ground at 8 a.m. and the Colonel arrived on the Battalion parade ground at 9 a.m. He rode round the Battalion. When he reached my platoon he called me up to him and asked me whether I had a roll of my platoon. I replied that I had. He asked me whether I had it on me; and I replied that I had, and produced it. He seemed perfectly satisfied. He also asked me one or two other questions; to all of which I was able to give a satisfactory answer. And last night as I passed him in the road and saluted he smiled most affably and said 'good evening.' So he is quite agreeable with me so far.

I do not therefore yet join in the general condemnation of him. As far as I can tell at present his chief faults appear to me to be: that he suffers from a badly swelled head; that he fancies himself a budding Napoleon; that he is endowed by the fates with a very bad temper and a most vile tongue; that he is inconsiderate of his inferiors wherever his personal whims and ambitions are concerned; and that he is engrossed with an inordinate desire to be in the good graces of the Brigadier-General, who is really, I believe, a very good sort. Apart from those failings, some of which are, perhaps, excusable, I think he is probably all right. You may be sure that his unpopularity will not prejudice me against him; I shall not join in the general condemnation unless and until he gives me good reason. As yet I have no such reason. Up to now his personality is merely a source of curiosity and amusement.'

It seems from all accounts that by this point he had also developed a minor twitch, no doubt the long-term manifestation of the shell-shock he had suffered as a result of the Somme battles. As the time wore on, his determination to drive and prepare his charges for their next test was the only thing in his mind. He was ordered to take them on a punishing 16 mile march on 16 June 1917. Floyd again:

'Brigadier-General Stockwell rode up from the opposite direction (on horseback) and, with a face wincing with wrath, accosted Colonel Best-Dunkley as follows:

'Dunkley, where's your Battalion?'

'This is my Battalion here, sir,' replied the Colonel, standing submissively to attention and indicating fifteen officers, non-commissioned officers, and men - all told - lying in a state of exhaustion at the side of this shaded country road.

'What! You call that a Battalion? Fifteen men! I call it a rabble. What the bloody hell do you mean by it? Your Battalion is straggling all along the road right away back to (Watten)! You should have halted and collected them; not marched on like this. These men have not had a long enough halt or anything to eat all day. If this is the way you command a Battalion, you're not fit to command a Battalion. You're not even fit to command a platoon!'

The General then said that the Colonel, the Adjutant, and four company commanders could consider themselves 'under arrest'! The General was simply fuming with wrath; I do not think I have ever seen a man in such a temper. And I certainly never heard a colonel strafed in front of his own men before. It was an extraordinary scene. Those who have writhed under the venom of Colonel Best-Dunkley in the past would, doubtless, feel happy at this turning of the tables as it were, a refreshing revenge; but I must admit that my sympathy was with Colonel Best-Dunkley - and so was that of all present - in this instance, for we all felt that the General's censure was undeserved. It was not Colonel Best-Dunkley's fault; if it was anybody's fault it was the General's own fault for ordering the march by day instead of by night, and for not halting the Brigade for a long enough period earlier on in the course of the march. One felt that Colonel Best-Dunkley was being treated unjustly, especially as the North Lancs. had only arrived with ten! And the Irish had not yet arrived at all! (These facts must soon have become apparent to General Stockwell, and, perhaps, caused him, inwardly at any rate, to modify his judgment). And the way Colonel Best-Dunkley took it, the calm and submissive manner in which he bore General Stockwell's curses and the kind and polite way in which he afterwards gave orders to, and conversed with, his inferiors, both officers and men, endeared him to all. I consider that out of this incident Colonel Best-Dunkley has won a moral victory. He played his cards very well, and feeling changed towards him as a result.'

On Waterloo Day, the Officers learned from the Colonel that a great new plan was in the off and that it was one that they were to share in. Best-Dunkley conferred it was to be the greatest Battle of the War and one that could result in peace for one and all if it were a total success.

Mustard Gas - 12 July

The Battalion continued to train themselves for the coming 'push' and were back in the Ypres getting themselves ready for action. It was to be on 12 July that they came under attack from 'Mustard Gas' - which cost them 3 Officers and 114 other ranks. Floyd takes up the story:

'Captain Blamey, Captain Bodington, Captain Briggs and Gratton were in for dinner yesterday evening. Gratton is now Assistant Adjutant at Headquarters. Every day Colonel Best-Dunkley goes to a certain house (Hasler House at St. Jean) which has an upstairs still left, and, through field-glasses, gazes at the front over which we shall have to advance. On these trips Gratton accompanies him, and has to take bearings and answer silly questions. He says that he is becoming most horribly bored with it all. While they were at it yesterday a shell exploded just by them. Gratton says that he jumped down below as soon as he heard it come; he was hit by one or two bricks and covered with dirt; when he looked round again he expected to find the Colonel done in, but found him safe and sound!

Yesterday evening Captain Andrews, Giffin, Dickinson and Allen all went out on working parties. I remained behind as Orderly Officer. Captain Briggs and Gratton remained in my dug-out with me. After a while Gratton had to go to Brigade Headquarters next door to discuss a map with the Brigade-Major. Soon after he had left us—about 10.10 p.m.—a terrific shelling of the city began. Shells were bursting everywhere; the ground frequently vibrated as if mines were going off; dumps were blown up; and very soon parts of the city were in flames. It was a sight such as I have never seen before; at times the whole scene was as light as day; the flames encircled the already ruined and broken houses, bringing them to the ground with a rumbling crash. It was a grand and awful sight—a firework display better than any at Belle Vue, and free of charge! The sky was perforated with brilliant yellow light, and the shells were whizzing and crashing all round. The air was thick with sulphur. So much so that we did not smell something much more serious than sulphur. Amidst all the turmoil little gas-shells were exploding all over. As we could not smell the gas we did not take any notice of it. We little dreamt what the results were going to be. We knew not what a revelation the morrow had in store for us!

At about midnight I went to bed, and at about 6 this morning I heard Giffin returning from his working party. He was muttering something about gas and saying that he would be going sick with it in a few days, but I was too sleepy to take much notice. I rose at 10.30 and made my personal reconnaissance of the road, but only found two very serious shell-holes actually on the road. These I pointed out to Sergeant Baldwin and got his men at them. Then I began to hear things about gas. I saw Corporal Flint (our gas N.C.O.!) being led by Sergeant Donovan and Corporal Livesey in a very bad state; he could hardly walk, his eyes were streaming, and he was moaning that he had lost his eyesight. So I began to inquire as to what was the matter. I was then informed that there had been a whole lot of men gassed. Then Captain Andrews sent for me and questioned me about gas last night. I told him frankly that I had not smelt any. He said that it was very strange, because when he got back early this morning 'the place simply stank of it.' He said that there would be a devil of a row about it; there were about ten casualties already! But, as time went on, the numbers began to grow rapidly. Yet I had not smelt it; the sentry had not smelt it; and the Sergeant-Major had not smelt it! After some time the Colonel appeared on the scene. He informed us that A Company had got seventy-two casualties from last night's gas! (A Company were billeted in the Soap Factory, near the Cathedral.) We felt a little relieved, because we realized that ours was not the only company and by no means the worst; so we could not be held responsible, as we were fearing that we might be—myself in particular, as the only officer on the spot at the time, for not ordering box-respirators on. I, of course, never thought of ordering box-respirators, considering that I smelt no gas myself! The Colonel further told us that three officers in A Company—Walsh, Hickey, and Kerr—were suffering from gas. Hickey is very bad.

During the day our casualties have risen considerably. They are now twenty-eight, including Corporal Flint, Corporal Pendleton, Corporal Heap, Pritchard, Giffin's servant, and Critchley, my servant. There have been heavy casualties all over the city. The Boche has had a regular harvest if he only knew it! Over a thousand gas-casualties have been admitted to hospital from this city to-day. And many who have not yet reported sick are feeling bad. So much so that the Brigade-Major has agreed that all our working parties, but one small one under Allen, shall be cancelled for to-night. I feel all right. I must have a strong anti-gas constitution. This is a new kind of gas; the effects are delayed; but I do not think I am likely to get it now since I have hardly smelt any yet.

The Germans are doing the obvious thing—trying to prevent or hinder our forthcoming offensive. I notice that they have attacked near Nieuport and advanced to a depth of 600 yards on a 1400 yards front. I have been expecting an enemy attack here, because it is the best thing the Germans can do if they have any sense; and I have repeatedly said so, but have been told that I am silly, that the Germans dare not attack us because they are not strong enough. For a day I held the view that peace was coming in a week or two! But Bethmann-Hollweg's straightforward declaration that Germany will not make peace without annexations or indemnities, that she is out to conquer, has altered things. We now know exactly how we stand. Germany is still out for grab. Therefore she is far from beaten. Ipso facto, peace is out of the question. The end is not yet in sight. There is still a long struggle before us. I think the forthcoming battle here will be the semi-final: the final will be fought in the East about Christmas or the New Year. Constantinople still remains the key to victory, if victory is to be won by fighting.'

The total casualties in Ypres as a result of the novel 'Yperiet' mustard gas were over 3,000 - poor timing indeed when in just a few days the great attack was to take place.

Judgement Day - 31 July 1917

The 2/5th Battalion remained in Ypres for another week before going up into the trenches. This was far from a time of rest and activity was high. Final preparations were to be made and they were almost constantly under shelling. Floyd wrote home in a letter of 21 July:

'After tea yesterday I went up to the trenches to reconnoitre our own positions as they will be on 'the day,' and the front over which we shall have to advance. I was accompanied by Allen and others. We got there and back again without any adventures whatever; but we saw crowds of batteries bombarding the German lines. The noise as we passed them was deafening. And through our glasses we saw the German lines going up in smoke. If the artillery fails to achieve exactly what the General orders the infantry is foredoomed to failure; and, conversely, if the artillery is successful the infantry ought to have things all plain sailing. That was the secret of the victory of Messines last month. Churchill, with his customary intelligence, has aptly summed up the matter in the following words:

"In this war two crude facts leap to the eye. The artillery kills. The infantry is killed. From this arises the obvious conclusion - the artillery at its maximum and infantry at its minimum."'

As it will prove, the Artillery indeed kills. He continues:

'We eventually got to our destination, a certain camp. We stayed the night there. We tried to get some sleep on the floor in a large elephant dug-out, but found it utterly impossible: the sound of the guns all round was too terrific. This bombardment is as yet only in its early stages. I was only a few hundred yards away from where I was last night on that night previous to the night of the Battle of Messines when the preliminary bombardment for that battle was at its height; yet I may say that the present one sounded last night just like that one sounded then. So what will it become as the days roll on?

We had breakfast at 4 this morning and marched off from this camp at 6.40. We marched about nine miles to a village which was really only about six miles away! I can tell you I was, and we all were, very tired indeed when we got here. It was about midday when we arrived. We are still well in sound of the guns, but just nicely out of range of them. Nevertheless, air scraps have been going on overhead most of the day. We are under canvas—the whole battalion in a large field enclosed by hedges. The weather is splendid; fine camping weather. We had lunch about 2 p.m. Then I played a game something like tennis (badminton). The Colonel is very keen on it. When he saw that I was going to play he said, 'Oh, I'll back the "General,"' meaning me! Then he showed me how to play. He has been most agreeable with me all day. Major Brighten has started calling me 'The Field-Marshal!' I think I cause these gentlemen considerable amusement!'

The unit made it to Camp at Watou and waited on the bombardment to grow to its crescendo. By 25 July he wrote of a happy arrival for Best-Dunkley:

'It was at this time that news came across that a son and heir had been born to Colonel Best-Dunkley. The event was one of considerable interest, and was widely discussed.

"Poor little -------! To think that there's another Best-Dunkley in the world to look forward to!" exclaimed our humorous friend when he heard the news. "Well, when he grows up he will always have the gratification of knowing that his father was a Colonel in the Great War!" mused Captain Andrews in a tone which suggested that he had a presentiment that Colonel Best-Dunkley would not survive the coming push.

And, somehow - though nobody ever anticipated for a moment that he would win the V.C. - we all discussed the probability of his falling, and always thought that the odds were in favour of his falling. And to be perfectly frank (my object in writing this book is to tell the truth), nobody regretted the probability! If we had really known what kind of a man he was, if we had been able then to fathom beneath the forbidding externals, we might have felt very differently about it. But it is not given to man to know the future or even to discern the heart of his most intimate acquaintance! We only saw in him a man who was as unscrupulous as his prototype Napoleon in all matters which affected his own personal ambition, the petty tyrant of the parade ground, who could occasionally be very agreeable, but of whom all were afraid or suspicious, because none knew when his mood would change. In a few days this man was going to give everybody who knew him the surprise of their lives. Had he any presentiment or intention as to the future himself? I think he had both intention and presentiment. Throughout the whole summer of 1917 his whole heart and soul were absorbed in preparation for the coming push; never did a man give his mind more completely, unstintingly, and whole-heartedly to a project than Best-Dunkley did to the Ypres offensive which was to have carried us to the Gravenstafel Ridge, then on to the Paschendaele Ridge, into Roulers and across the plains of Belgium. He was determined to associate his name indelibly with the field of Ypres; he was determined to win the highest possible decoration on July 31: he knew what the risks were; he had seen enough of war to know what a modern push meant; he had not come through Guillemont and Ginchy for nothing and learnt nothing; he was determined to stake life and limbs and everything on the attainment of his ambition. He was determined to cover himself with glory; he was determined to let people see that he did not know what fear was.

And I think - there was that in his bearing the nearer the day became which suggested it, everybody who had known him of old declaring that they noticed a certain change in him during the last two months of his life - that he felt that his glory would be purchased at the cost of his life.

I well remember one afternoon in the Ramparts when Captain Andrews came in and told us that it had been proposed that Major Brighten should take the Battalion over the top in the push and the Colonel remain behind on "battle reserve." Captain Andrews said that that would be fine, because if the push were a success - as it was sure to be - Major Brighten would probably get the D.S.O. before the Colonel, which would annoy the Colonel intensely; and he said that he would do anything, risk anything to bring success to our beloved Major Brighten - feelings which we all cordially reciprocated. But Colonel Best-Dunkley would not hear of it. He implored the General to allow him to lead his Battalion over the top; he waxed most importunate in his entreaties, almost bursting into tears at the thought of being debarred from going over with the Battalion; and, at last, his request was granted and the General agreed that Best-Dunkley should take the Battalion over.'

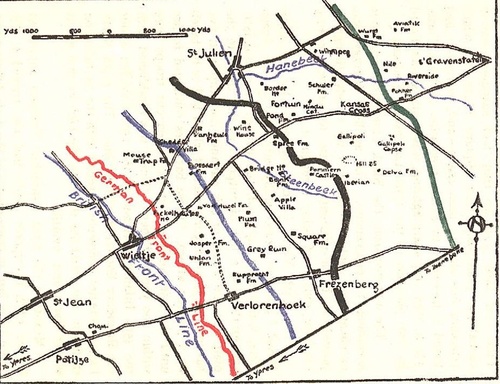

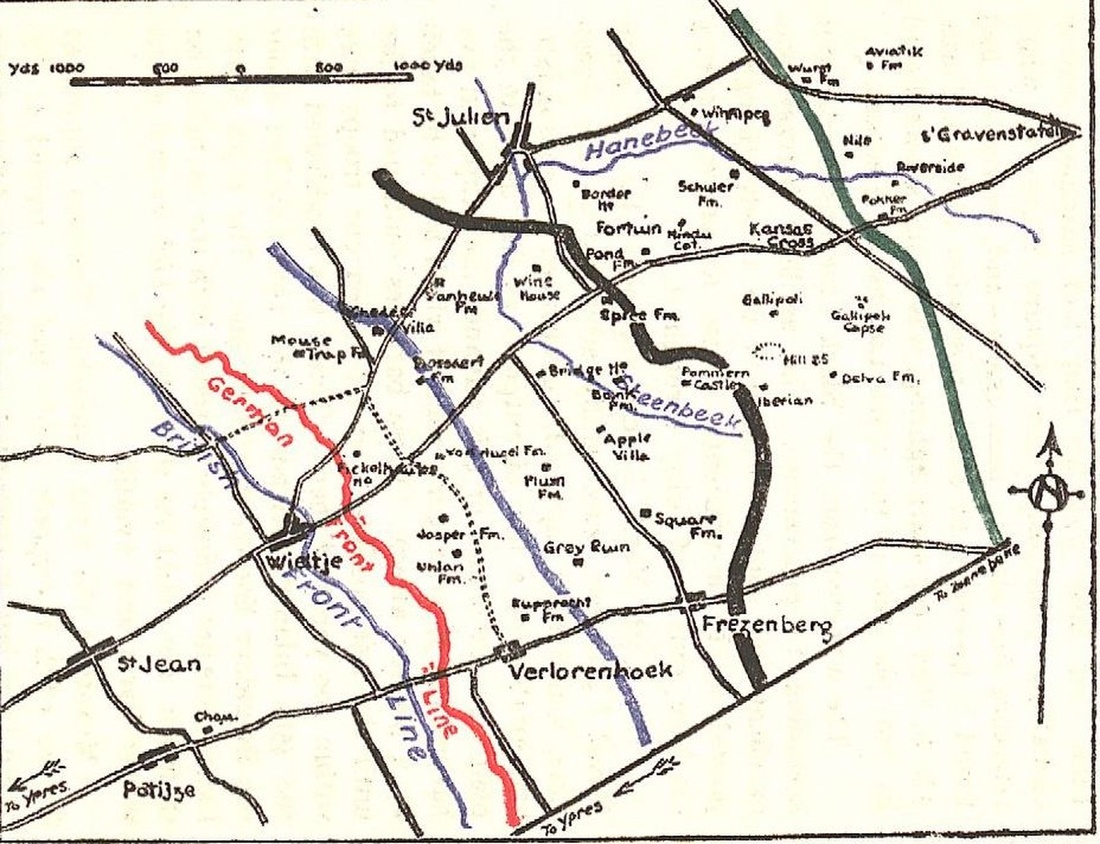

So it was, the unit marched up to Query Camp, near Brandhoek on the night of 25 July. They went up to the concentration trenches near Vlamertinghe on 'XY Night' and prepared for 'Z Day'. Battalion HQ was set up at Café Belge, on the Vlamertinghe-Ypres Road. The following night they went up assembly positions in the trenches known as 'Congreve Walk' and 'Liverpool Trench' close to Wieltje, making it at around 0130hrs on 31 July 1917. Floyd takes us there:

'Zero was fixed for 3.50 in the morning. As the moment drew near how eagerly we awaited it! At 3.50 exactly I heard a mine go up, felt a slight vibration, and, as I rushed out of the little dug-out in which I had been resting, every gun for miles burst forth. What a sight! What a row! The early morning darkness was lit up by the flashes of thousands of guns, the air whistling and echoing with shells, the calm atmosphere shaken by a racket such as nobody who has not heard it could imagine! The weird ruins of Ypres towered fantastically amongst the flashes behind us. In every direction one looked guns were firing. In front of us the 166th and 165th Brigades were dashing across No Man's Land, sweeping into the enemy trenches, the barrage creeping before them. I stood on the parados of Liverpool Trench and watched with amazement. It was a dramatic scene such as no artist could paint.

Before the battle had been raging half an hour German prisoners were streaming down, only too glad to get out of range of their own guns! I saw half a dozen at the corner of Liverpool Trench and Garden Street. They seemed very happy trying to converse with us. One of them - a boy about twenty - asked me the nearest way to the station; he wanted to get to England as soon as possible!

The Tanks went over. As daylight came on the battle raged furiously. Our troops were still advancing. Messages soon came through that St. Julien had been taken.

Our time was drawing near. At 8.30 we were to go over. At 8 we were all 'standing to' behind the parapet waiting to go over. Colonel Best-Dunkley came walking along the line, his face lit up by smiles more pleasant than I have ever seen before. 'Good morning, Floyd; best of luck!' was the greeting he accorded me as he passed; and I, of course, returned the good wishes. At about 8.20 Captain Andrews went past me and wished me good luck; and he then climbed over the parapet to reconnoitre. The minutes passed by. Everybody was wishing everybody else good luck, and many were the hopes of 'Blighty' entertained - not all to be realized. It is a wonderful sensation - counting the minutes on one's wrist watch as the moment to go over draws nigh. The fingers on my watch pointed to 8.30, but the first wave of D Company had not gone over. I do not know what caused the delay. Anyhow, they were climbing over. Eventually, at 8.40, I got a signal from Dickinson to go on.

So forward we went, platoons in column of route. Could you possibly imagine what it was like? Shells were bursting everywhere. It was useless to take any notice where they were falling, because they were falling all round; they could not be dodged; one had to take one's chance: merely go forward and leave one's fate to destiny.

Thus we advanced, amidst shot and shell, over fields, trenches, wire, fortifications, roads, ditches and streams which were simply churned out of all recognition by shell-fire. The field was strewn with wreckage, with the mangled remains of men and horses lying all over in a most ghastly fashion - just like any other battlefield I suppose.

Many brave Scottish soldiers were to be seen dead in kneeling positions, killed just as they were firing on the enemy. Some German trenches were lined with German dead in that position. It was hell and slaughter. On we went.

About a hundred yards on my right, slightly in front, I saw Colonel Best-Dunkley complacently advancing, with a walking stick in his hand, as calmly as if he were walking across a parade ground. I afterwards heard that when all 'C' Company officers were knocked out he took command in person of that Company in the extreme forward line. He was still going strong last I heard of him.'

The scene was clearly one of true horror but the first objectives were taken by the 164th Brigade. By 0900hrs they had were pushing onto the 'Green Line', the German third line system some mile beyond the 'Black Line', with the exception of Spree Farm and Wine House. With the 2/5th Battalion putting in their attack initial success was met until they hit the Hanebeek stream, coming into machine-gun and rifle fire, this intensifying as they pushed on a few hundred yards. The Companies were forced out into extended order, however, the concentration of steel they faced meant men fell all about and it was all but impossible to retain formation.

Floyd gave his account of the scene and his own wounding:

'We left St. Julien close on our left. Suddenly we were rained with bullets from rifles and machine-guns. We extended. Men were being hit everywhere. My servant, Critchley, was the first in my platoon to be hit. We lay down flat for a while, as it was impossible for anyone to survive standing up. Then I determined to go forward. It was no use sticking here for ever, and we would be wanted further on; so we might as well try and dash through it. 'Come along—advance!' I shouted, and leapt forward. I was just stepping over some barbed wire defences—I think it must have been in front of Schuler Farm (though we had studied the map so thoroughly beforehand, it was impossible to recognize anything in this chaos) when the inevitable happened.

I felt a sharp sting through my leg. I was hit by a bullet. So I dashed to the nearest shell-hole which, fortunately, was a very large one, and got my first field dressing on. Some one helped me with it. Then they went on, as they were, to their great regret, not hit! My platoon seemed to have vanished just before I was hit. Whether they were in shell-holes or whether they were all hit, or whether they had found some passage through the wire, I cannot say.'

Spotting that all the Officers of 'C' Company had become casualties, Best-Dunkley rushed forward and personally led the Company through the hail of fire with great coolness and bravery. He was well on the way to earning his laurels and the 'Black Line' was taken.

At this point the 2/5th Battalion had lost around half of their strength, without assistance from the tanks which had been charged with assisting - their attack was halted due to the ground turning into a quagmire from the shellfire and heavy rainfall that occured during the day. Another factor was the requirement to keep up with the creeping barrage which was being laid to sheild the attack. To fall further behind would make life even more difficult.

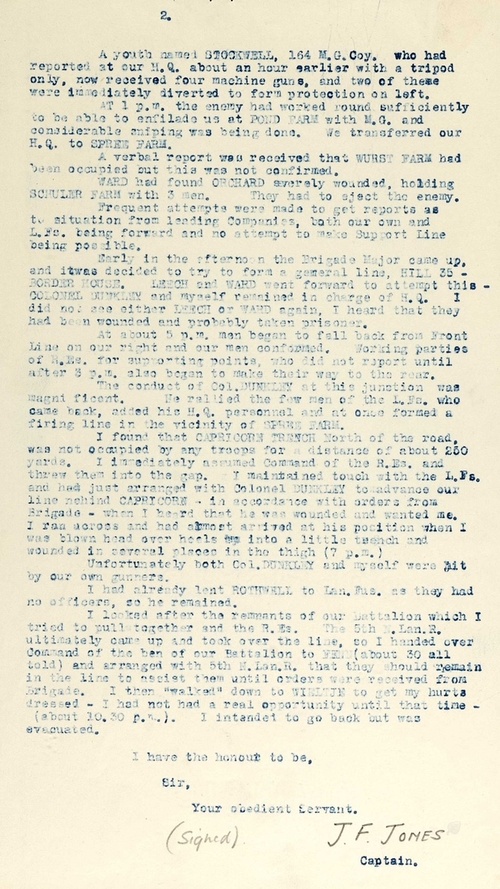

So it was, they continued to push on to take the vital points of Wine House, Spreey Farm and Capricorn Support, with Best-Dunkley setting up his HQ in the Farm. By now, the unit was merged together with the 1/8th (Liverpool Irish) King's Regiment at the HQ, both units being made up of the small and gallant band who had make it past noon. Small parties thence went outwards to continue to take the fight to the enemy, however, it wasn't long before they themselves began to counter. Lieutenant Bodington's 'D' Company reached Wurst Farm with a party of ten men, of whom eight soon became casualties. Having held their objectives for barely an hour, the enemy began to throw men in from the north-east. Those few who held Wurst Farm were forced to withdraw to Winnipeg Farm to stop themselves being cut off. At this time in the mid-afternoon, German artillery began to be called into action. Its intensity and accuracy grew and those who still stood were being enfiladed from both flanks and attacked from the air, not to mention the ordnance which continued to rain down onto them.

So it was the 'Black Line' was to be the final standing point for the unit. The remnants of the 2/5th Battalion and the 1/8th Battalion numbered around 130 men and stood firm at Schuler Farm, whilst the HQ, with Best-Dunkley, was made at Spree Farm. It didn't take long for another attack to come in from the enemy, who took out another eighty of them. There was little option but to fall onto Spree Farm. The account of two members of the 1/8th Battalion (Liverpool Irish) now offer a first-hand account of the final actions of Best-Dunkley; he truly showed his mettle. The Regimental History also sets the scene of this crucible, for '...at that time also rain came down in torrents and continued; shell holes filled with water; mud became slime; the conditions were completely discouraging.'

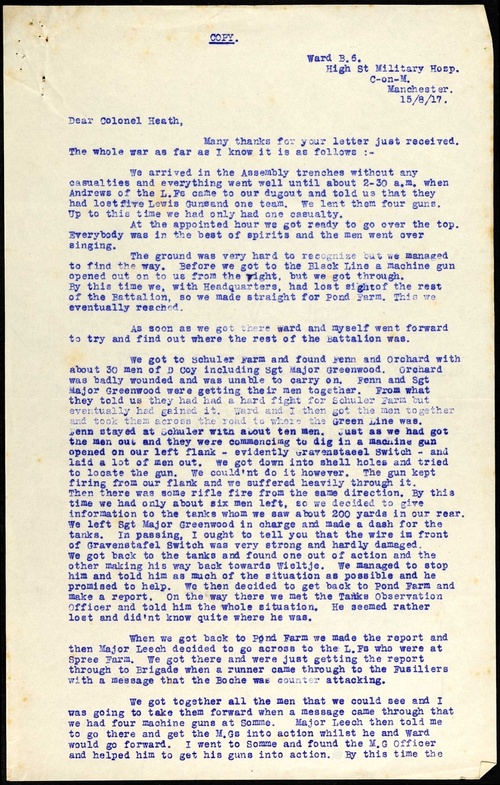

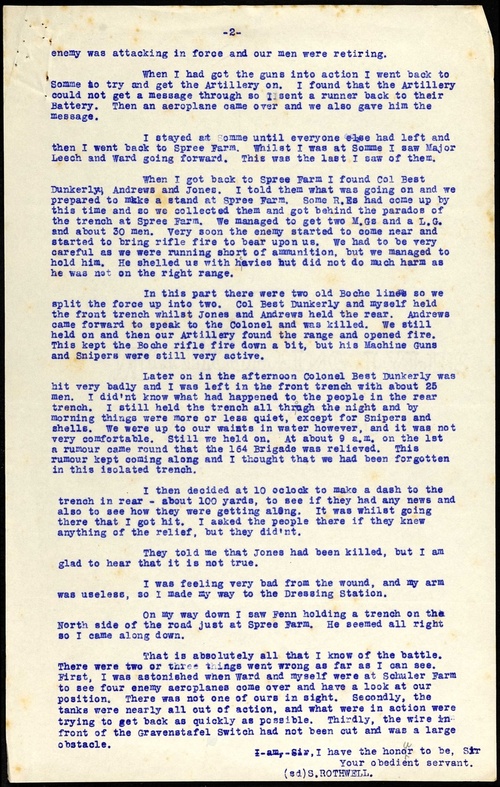

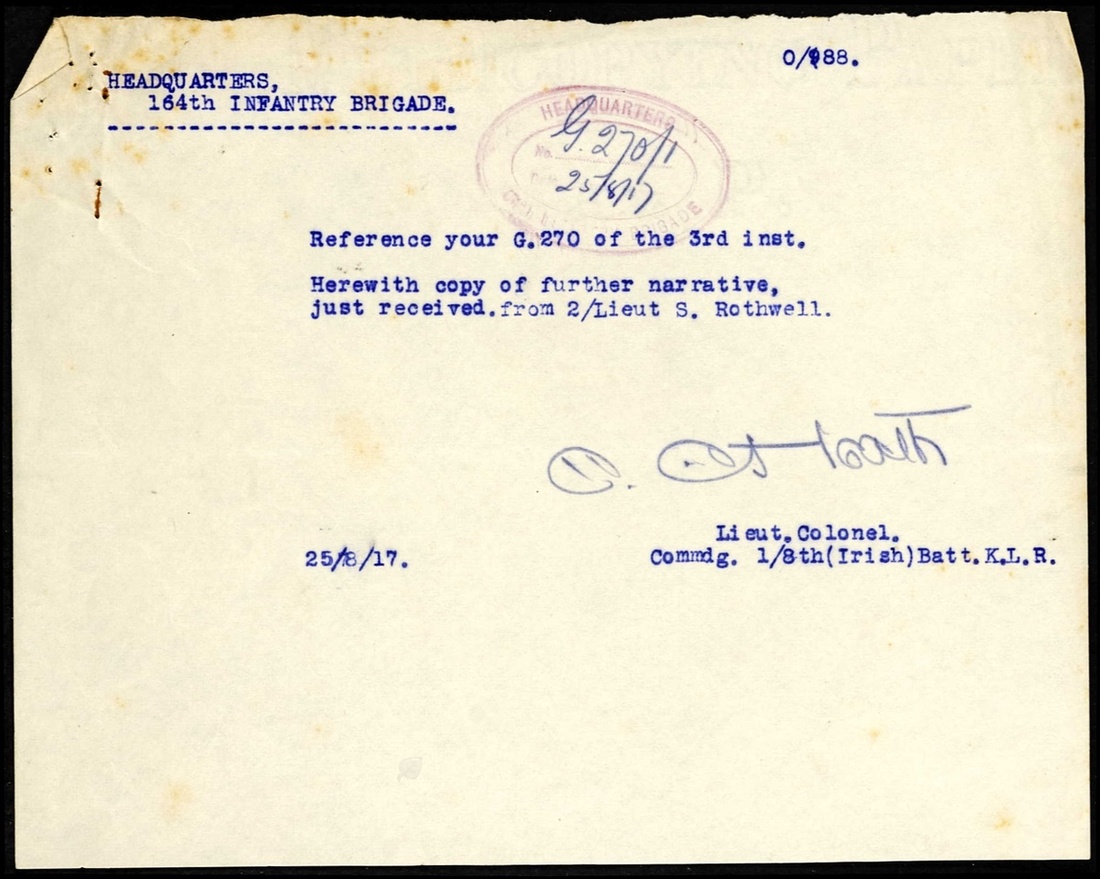

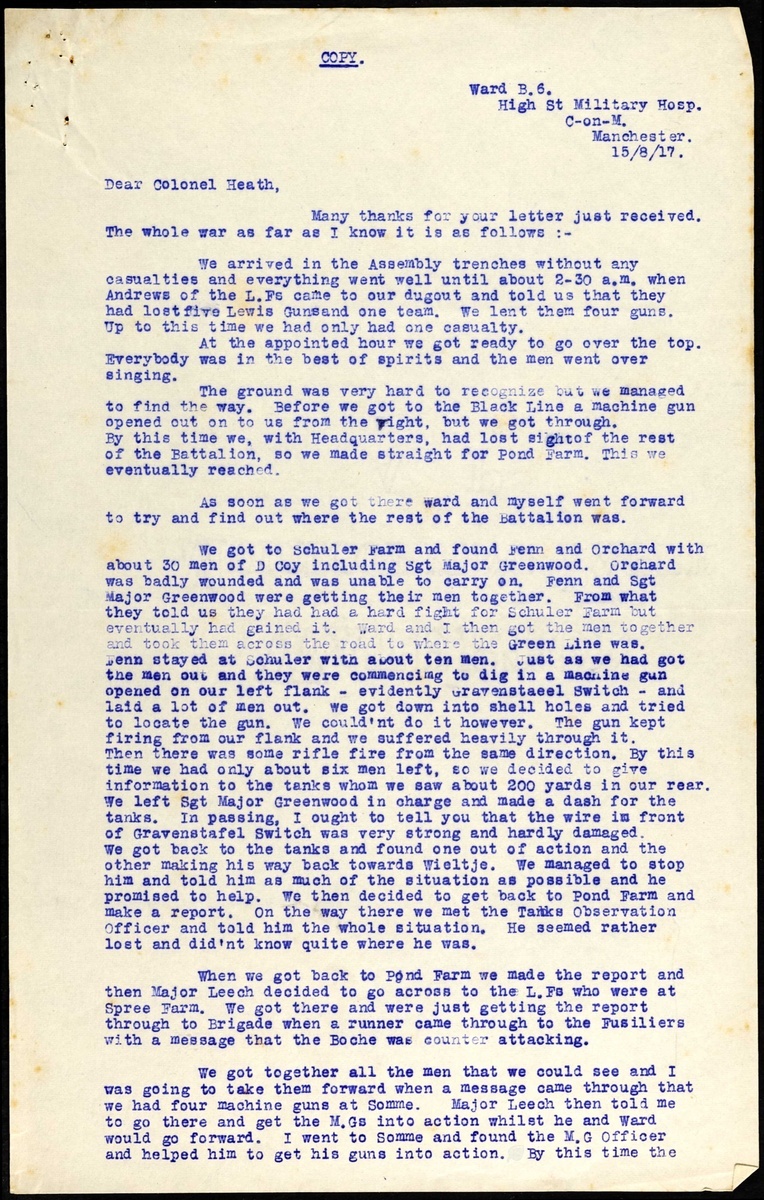

S. F. Rothwell gave his account on 15 August 1917, having been evacuated to the High Street Military Hospital, Manchester:

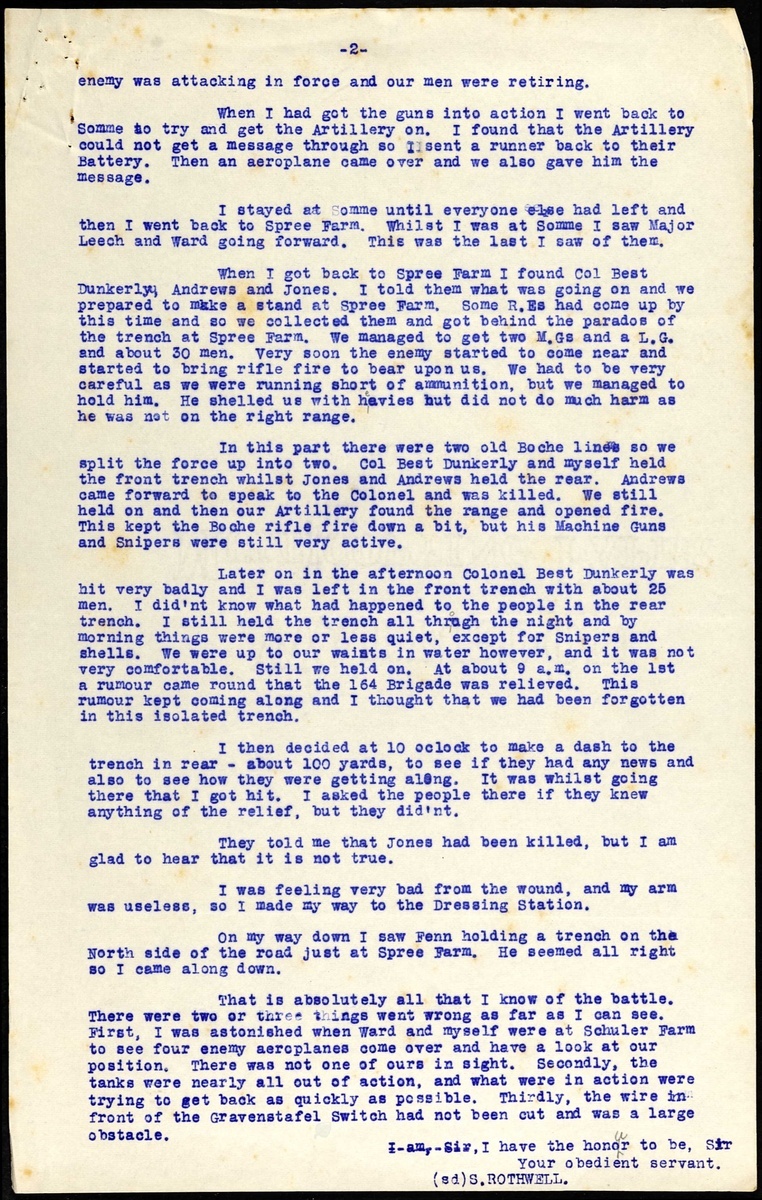

'When we got back to Pond Farm we made the report and then Major Leech decided to go across to the L.F.s [Lancashire Fusiliers] who were at Spree Farm. We got there and were just getting the report through to Brigade when a runner came through to the Fusiliers with a message that the Boche was counter attacking...I found Col Best-Dunkely, Andrews and Jones. I told them what was going on and we prepared to make a stand at Spree Farm. Some R.E.s had come up by this time and so we collected them and got behind the parados of the trench at Spree Farm. We managed to get two MGs and a LG and about 30 men. Very soon the enemy started to bring rifle fire to bear upon us. We had to be very careful as we were running very short of ammunition, but we managed to hold him. He shelled us with heavies but did not do much harm as he was not on the right range.

In this part there were two old Boche lines so we split the force up into two. Col. Best-Dunkley and myself held the front trench whilst Jones and Andrews held the rear. Andrews came on forward to speak to the Colonel and was killed. We still held on and then our Artillery found the range and opened fire. This kept the Boche rifle fire down a bit, but his Machine Guns and Snipers were still very active.

Later on in the afternoon Colonel Best-Dunkley was hit very badly and I was left in the front trench with about 25 men. I didn't know what happened to the people in the rear trench. I still held the trench all through the night and by morning things were more or less quiet, except for Snipers and shells.

We were up to our waists in water however, and it was not very comfortable.'

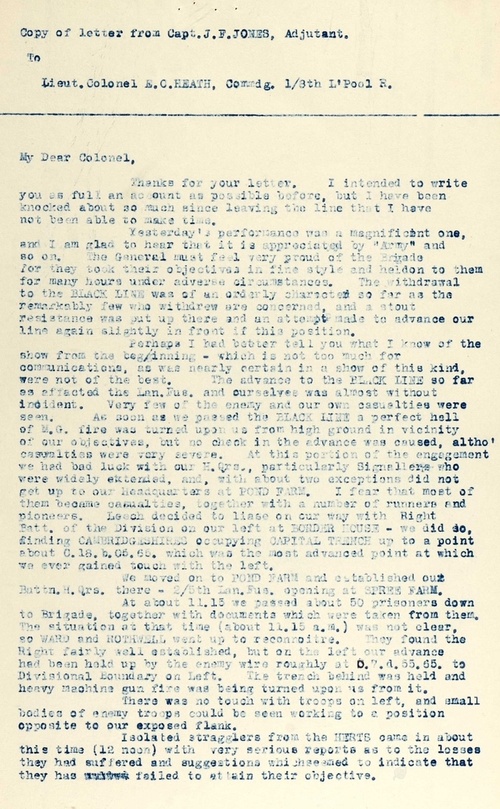

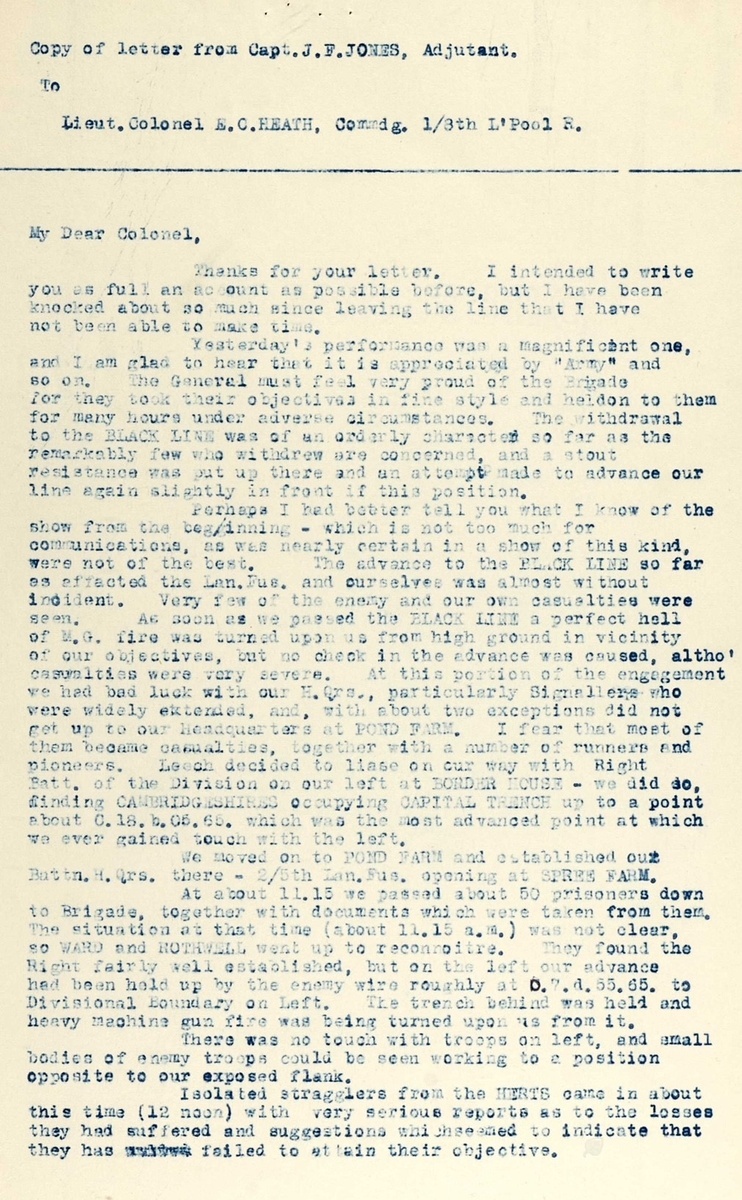

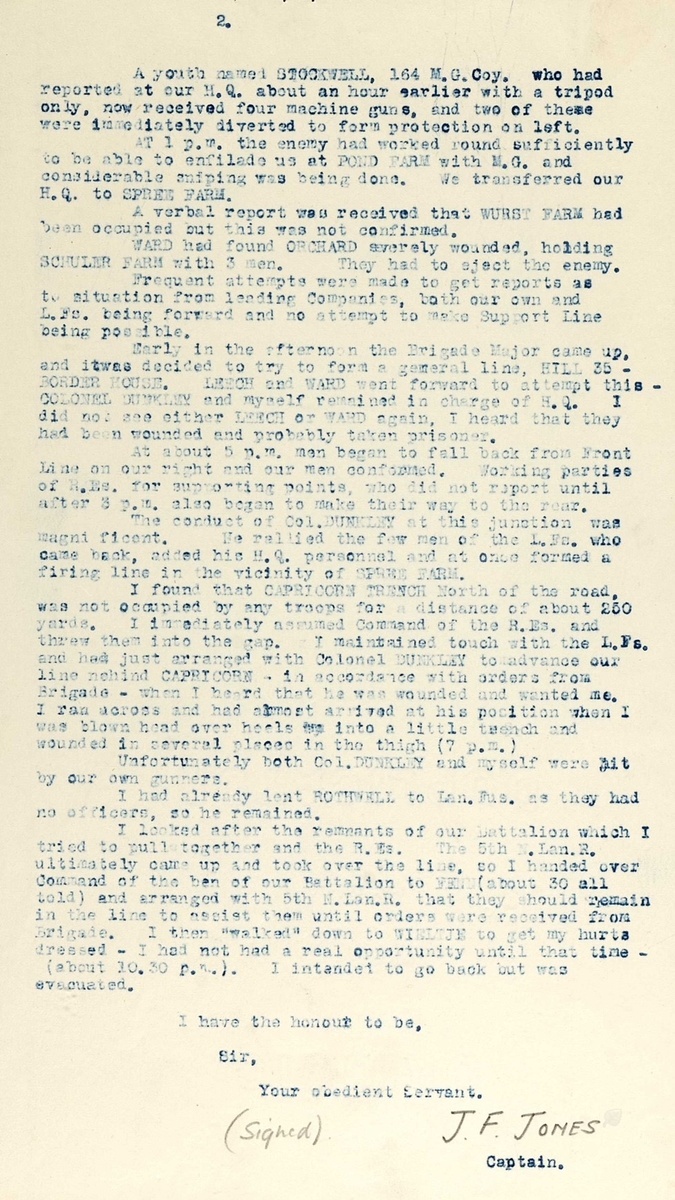

The gallant actions performed that day were also recalled by Captain J. F. Jones, who sheds light on the true cause of the mortal wounds to Best-Dunkley:

'Early in the afternoon the Brigade Major came up and it was decided to try to form a general line, Hill 35 - Border House. Leech and Ward went forward to attempt this- Colonel Dunkley and myself remained in charge of H.Q. I did not see either Leech or Ward again. I heard that they had been wounded and probably taken prisoner [Both were killed].

At about 5 p.m. men began to fall back from Front Line on our right and men conformed. Working parties of Royal Engineers for supporting points, who did not report until after 3 p.m. also began to make their way to the rear.

The conduct of Col. Dunkley at this junction was magnificent. He rallied the few men of the Lancashire Fusiliers who came back, added his H.Q. Personnel and at once formed a firing line in the vicinity of Spree Farm.

I found that Capricorn Trench north of the road was not occupied by any troops for a distance of about 250 yards. I immediately assumed Command of the Royal Engineers and threw them into the gap. I maintained touch with the Lancashire Fusiliers and had just arranged with Colonel Dunkley to advance our line behind Capricorn - in accordance with orders from Brigade- when I heard that he was wounded and wanted me. I ran across and had almost arrived at his position when I was blown head over heels into a little trench and wounded in several places in the thigh (7 p.m.).

Unfortunately both Col. Dunkley and myself were hit by our own gunners. '

So it was, Best-Dunkley earned his Victoria Cross in the act of making that final - successful - stand to retain the 'Black Line'. One can only imagine being up to one's waist in mud, water and the debris of such a hot contact. He stood firm, inspired his men and dared to make that stand.

Of the 19 Officer's who went into action that day, he was the last of 18 to be added to the Casualty List. 3 were killed outright, 2 were mortally wounded, 11 were wounded and 2 were missing. 593 Other Ranks went into action on 31 July 1917, 473 of them became casualties. As a percentage, that accounted for 88% of the 2/5th Battalion, Lancashire Fusiliers on the opening day of the Battle of Passchendaele.

Journey's End

Evacuated to the Casualty Clearing Station, on what was Minden Day, his comrades wore roses on their helmets in Bilge Trench. The message came down from Major-General Jeudwine, their Divisional Commander:

'Well done, 164, I am very proud of you. It was a fine performance and no fault of yours you could not stay.'

Upon the visit of the Divisional Chaplain, The Rev. James Coop, whispered that he had hoped the General was not too disappointed with the efforts of his own Battalion. The swift riposte came down:

'The padre has given me your message, and I am very much touched by it.

Disappointed? - I should think not, indeed. I am more proud of having you and your Battalion under my Command than anything that has ever happened to me.

It was a magnificent fight, and your Officers and men behaved splendidly, fighting with their heads as with the most superb pluck and determination.

The 31st July should for all time be remembered by your Battalion and Regiment and observed with more reverence even than Minden Day. It was no garden of roses that you fought in. I have heard some of the stories of your Battalion's doings and they are glorious. And I have heard of your doings too, and the close shave that you had.

Nothing would give me greater pleasure than that you should come back and command your Battalion, and I greatly hope you will. I am afraid you have painful wounds, but I trust they will not keep you long laid by.'

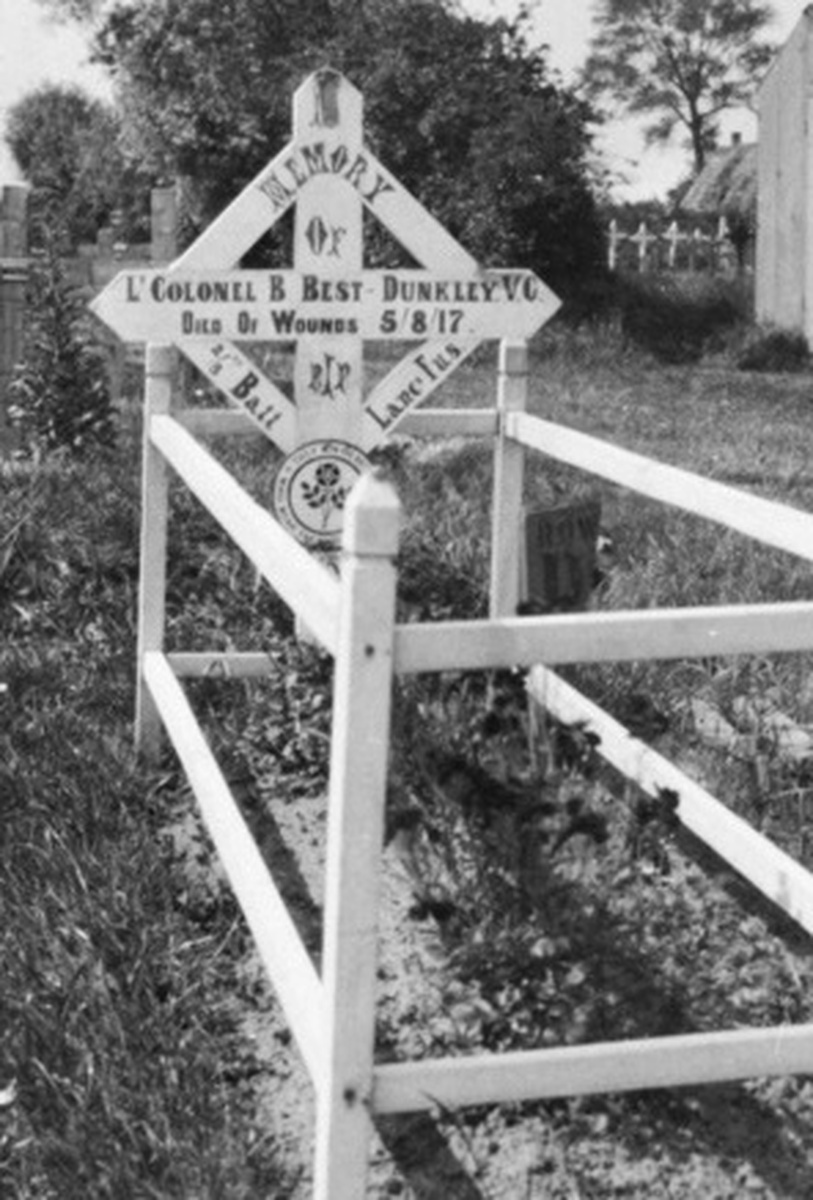

Having turned just twenty-seven years of age on 3 August, he succumbed to his mortal wounds on 5 August and was buried at Proven, at a service which the General rightly remarked:

'We are burying one of Britain's bravest soldiers.'

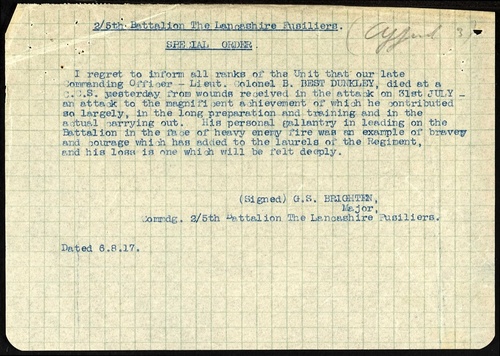

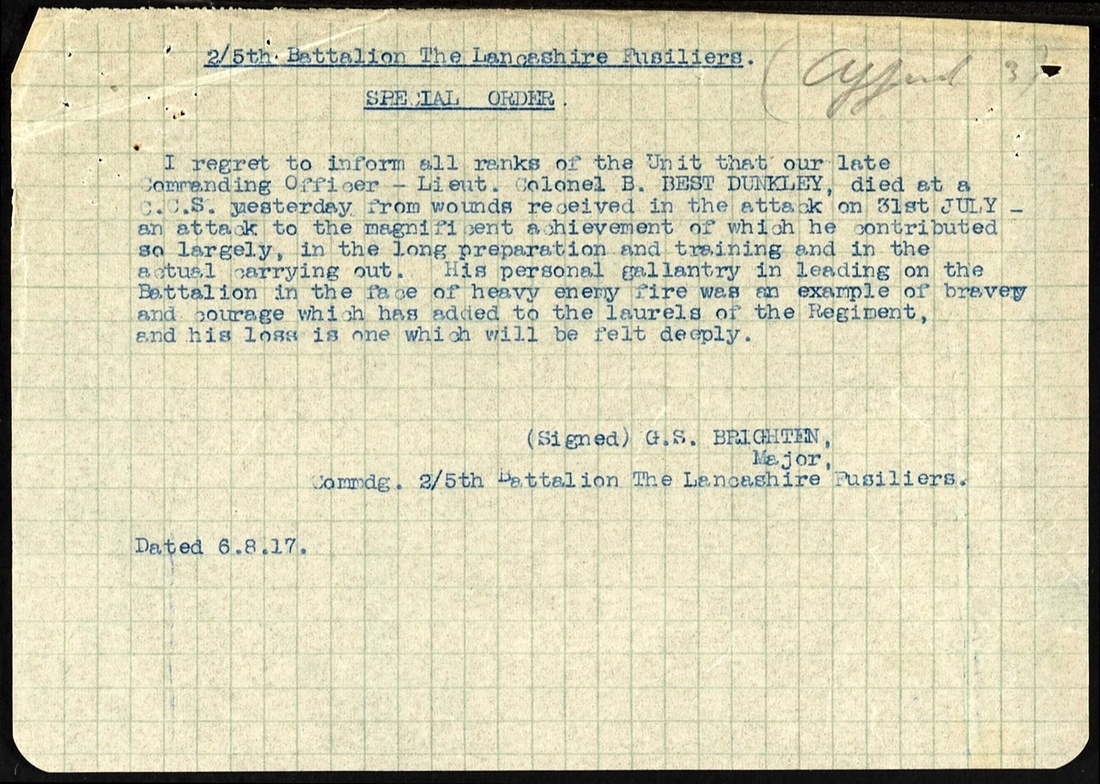

His body was latterly moved to Mendinghem Military Cemetery, Belgium. On 6 August, Major Brighten issued the Special Order to his unit:

'I regret to inform all ranks of the Battalion that our late Commanding Officer, Lieut.-Colonel B. Best-Dunkley, died at a C.C.S. yesterday from wounds received in the attack on 31st July - an attack to the magnificent achievement of which he contributed so largely in the long preparation and training and in the actual carrying out. His personal gallantry in leading on the Battalion in the face of heavy enemy fire was an example of bravery and courage which has added to the laurels of the Regiment, and his loss is one which will be felt deeply.'

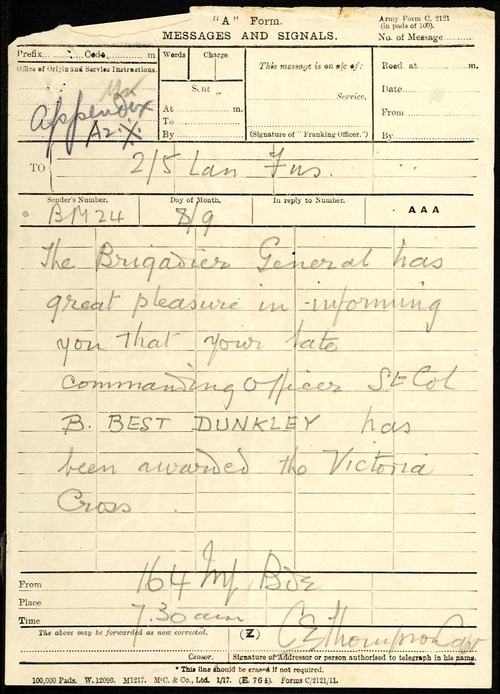

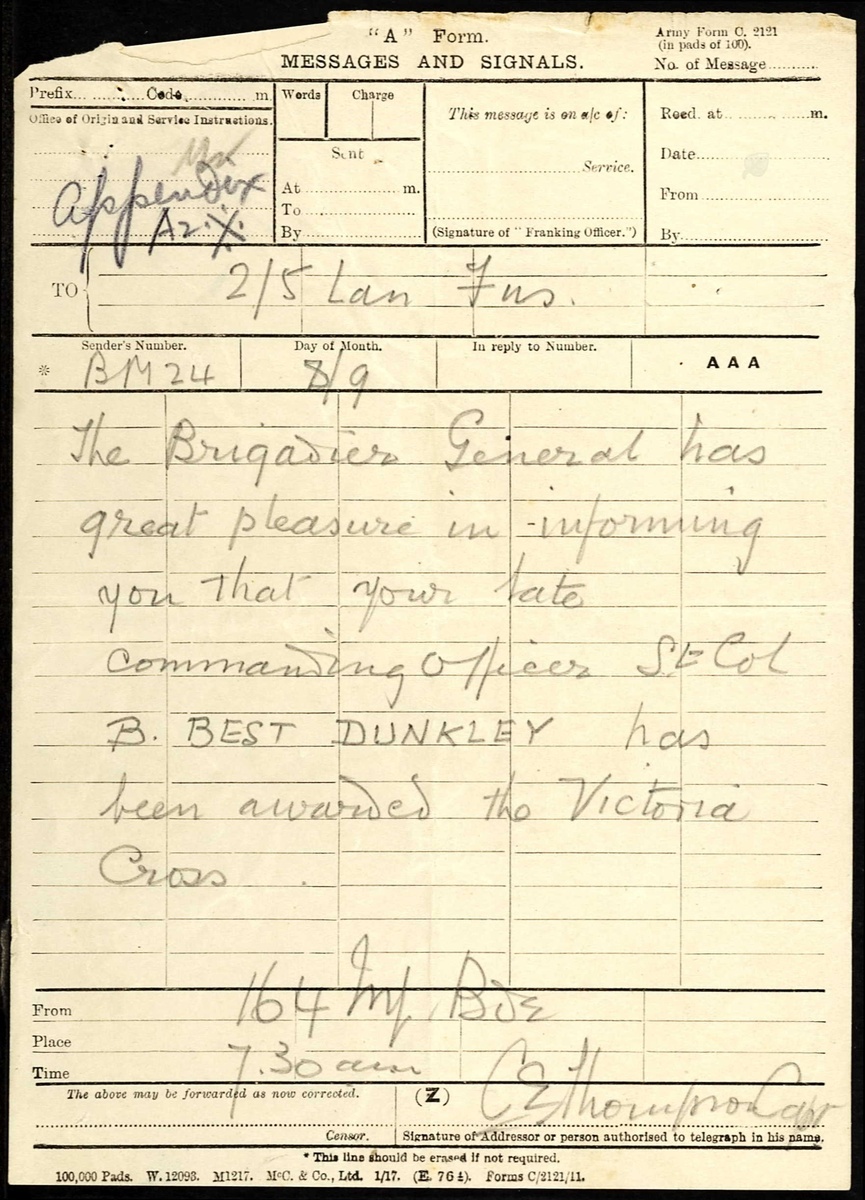

His son, Bertram Eric Lorimer Best-Dunkley, whom he never had the chance to meet, was just a few weeks old. Upon the swift promulgation of the award of his posthumous Victoria Cross, The King wrote to his widow:

'It is a matter of sincere regret to me that the death of Lt.-Col. Best-Dunkley deprives me of the pride of personally conferring on him the Victoria Cross, the greatest of all rewards for valour and devotion to duty.'

With his widow too ill to travel to Buckingham Palace, on 27 October 1917, Colonel Padley, Commander of the Barrow Garrison, pinned the Medal on the shawl of the infant Bertram at Risedale House, Barrow-in-Furness in a private investiture. His campaign Medals were claimed by his widow in January 1922. She lived at Crawley, West Sussex and died in 1980. His son served in the Royal Corps of Signals and died at Darlington in 2004.

A memorial was raised in his honour at the Tientsin Grammar School (now No. 20 Tianjin High School) and remains to this day, despite being slightly defaced during the Cultural Revolution, whilst a Victoria Cross paving stone was laid on the centenary of his action at Mount Vale, York.

Reference Sources:

VCs of the First World War - Passchendaele 1917, by Stephen Snelling.

The Lancashire Fusiliers, 1914-1918, by Major-General J. C. Latter.

At Ypres with Best-Dunkley, by T. H. Floyd.

The V.C. & D.S.O., by O'Moore Creagh.

The Register of the Victoria Cross.

Victoria Cross Heroes of World War One, by Robert Hamilton.

Passchendaele, by Peter Barton.

Passchendaele: 103 Days In Hell, by Alexandra Churchill.

Passchendaele: The Lost Victory of World War I, by Nick Lloyd.

The Story of the Third Battle of Ypres 1917, by Lyn MacDonald.

With thanks to Gavin Bassie - whose grandfather served in the 2/8th (Liverpool Irish) Battalion, King's Regiment during the Great War, which was to be combined with the 1/8th Battalion - for providing the letters of Rothwell and Jones.

Subject to 20% VAT on Buyer’s Premium. For more information please view Terms and Conditions for Buyers.

Sold for

£300,000

Starting price

£180000