Auction: 22003 - Orders, Decorations and Medals

Lot: 421

‘He was all that you could have desired and all that our race needs to keep its honour fair and bright.’

Winston Churchill, in a letter of condolence to Lord and Lady Desborough, the parents of Captain Hon. Julian Grenfell, D.S.O.

The important and poignant British Expeditionary Force 1914 operations D.S.O. group of five awarded to Captain The Hon. J. H. F. Grenfell, 1st Royal Dragoons, the noted war poet whose “Into Battle” received critical acclaim on being published by The Times on his death from wounds in May 1915 and became one of the most anthologized poems of the century

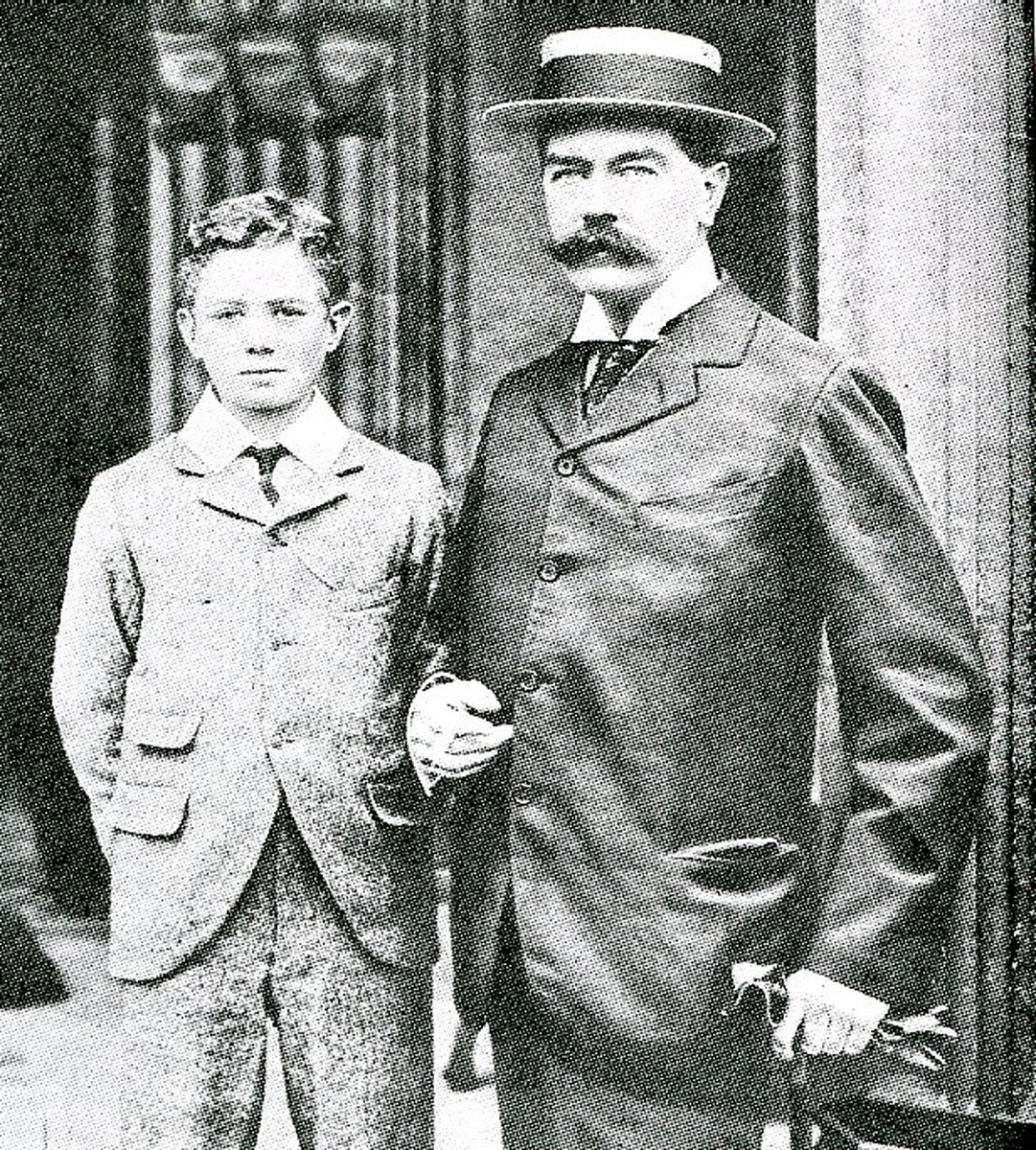

‘Brother, brother, if this be the last song you shall sing, sing well, for you may not sing another; Brother, sing’: more controversial was his declaration that he adored war - ‘It’s like a big picnic without the objectlessness of a picnic’ - but his fearless example in battle and marksmanship as a sniper won him the admiration of all, including Lord Kitchener who is said to have lost his composure on hearing of the poet’s demise

Distinguished Service Order, G.V.R., silver-gilt and enamel, in its Garrard & Co. case of issue; 1914 Star, clasp (Lt. Hon. J. H. F. Grenfell, 1/Dns.); British War and Victory Medals, with M.I.D. oak leaves (Capt. Hon. J. H. F. Grenfell); Coronation 1902, silver, in its Elkington & Co. case of issue, together with two Royal Dragoons badges, the campaign medals with original silk ribands, virtually as issued, extremely fine (5)

D.S.O. London Gazette 1 January 1915:

‘On 15 November 1914 he succeeded in reaching a point behind the enemy’s trenches and making an excellent reconnaissance, furnishing early information of an impending attack by the enemy.’

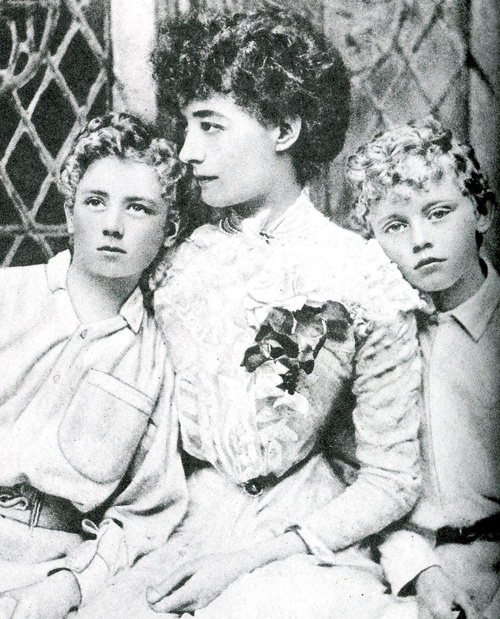

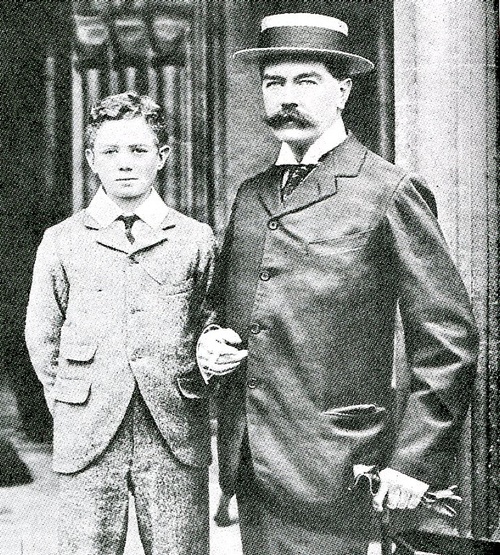

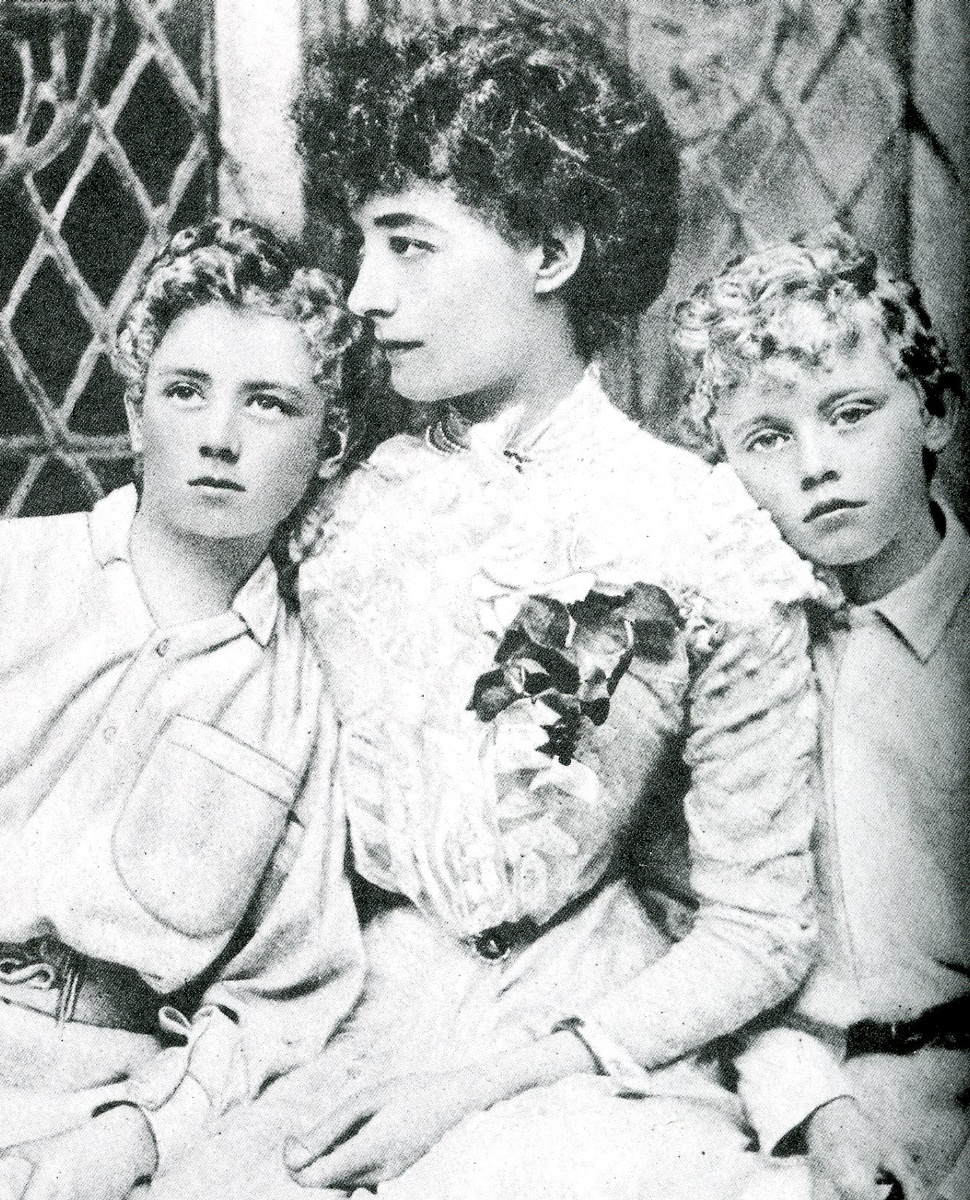

Julian Henry Francis Grenfell was born at 4, St. James’s Square, London, in March 1888, the elder son of William Henry, 1st Baron Desborough, K.C.V.O., and Ethel Priscilla, daughter of the Hon. Julian Henry Charles Fane, and grand-daughter of John, 11th Earl of Westmorland. Family connections put him in close contact with those at the high table of the Army, no less than Lord Kitchener, whom young Grenfell was to meet before the Boer War. He clearly had some effect on Kitchener, who wrote to him from the War:

'I got 80 (Boers) today, rather a good day.'

All round sportsman and emerging poet

Educated at Summerfields, Eton - where he edited the Eton College Chronicle and started The Outsider - and Balliol College, Oxford, young Julian was a multi-talented sportsman, his prowess as an athlete, boxer, horseman and oar being equalled by his reputation as a good shot, for as one biographer saw it, ‘he linked his belief to all the physical activities that he so much loved’.

Julian also rode in his new horse, Buccaneer, in the Oxford Open Heavyweight Race. He clearly fancied his chances and heavily backed himself at 4-1, the result was never in doubt and he '...won much gold.'

But from an early age he had also shown a talent for poetry, often including verse in his letters home and, in support of his love for the outdoor life, and loathing of the social gatherings favoured by his mother, once jested in a letter he sent from Eton - ‘I won’t go woman-hunting yet, I won’t be made a social pet!’

To his contemporaries at Oxford, he was a super-hero:

‘Julian did everything and shone in them all. He rowed, and he hunted, and he read and he roared with laughter, and he cracked his whip in the quad all night; he bought greyhounds from the miller of Hambledon, boxed all the local champions; capped poetry with the most precious of the dons and charmed everybody ... The only things he couldn’t stand were pose and affectation.’

Commissioned as a 2nd Lieutenant in the 1st Royal Dragoons in September 1909, he had embarked on a passionate affair with Pamela Lytton, wife of the 3rd Earl of Lytton of Knebworth. Such a liaison was not uncommon for a single gentleman of his prowess but she was left '...cut in half' when he was embarked for India with his unit. Stationed at Muttra, Grenfell wrote how he loved:

'...the sun and the cold and the Royal Dragoons, and my clothes, especially my boots, and rice and curry, and the Taj [Mahal], which takes my breath away.'

On being advanced to Lieutenant in October 1911, the unit moved on for South Africa, where, among other achievements, he took the High Jump Record of South Africa at six feet, five inches - and fought a spectacular boxing bout at Johannesburg:

‘A member who was in training for the Amateur Championship said he would come and fight me. He was a fireman called Tye; he used to be a sailor, and he looked as hard as a hammer. I quaked in my shoes when I saw him, and quaked more when I heard be was 2 to 1 on Hon. J. H. F. Grenfell, favourite for the Championship, and quaked most when my trainer went to see him, and returned with word that he had knocked out his men in a quarter of an hour. He went into the ring on the night, and he came straight at me like a tiger, and hit right; I stopped the left, but it knocked my guard aside, and he crashed his right clean on the point of my jaw. I was clean knocked out, but by the fluke of Heaven I recovered and came to and got on my feet again by the time they had counted six. I could hardly stand, and I could only see a white blur in front of me; but I just had the sense to keep my guard up, and hit hard at the blur whenever it came within range. He knocked me down twice more, but my head was clearing every moment, and I felt a strange sort of confidence that I was master of him.' I put him down in the second round, with a right counter which shook him; he took a count of eight. In the third round I went in to him and beat his guard down, then crossed again with the right, and felt it go right home, with all my arm and body behind it. I knew it was the end, when I hit; and he never moved for twenty seconds. They said it was the best fight they had seen in Johannesburg, and my boxing men went clean off their heads and carried me twice round the hall. I was 11 stone 4 lbs., and he was 11 stone 3 lbs., and I think it was the best fight I shall ever have.’

Meanwhile, his poetry continued to flourish, a Hymn to the Fighting Boar being penned in India, and a poem dedicated To a Black Greyhound in South Africa.

Granted home leave in September 1912, he attended parties in London with his brother Billy in pursuit of girls, and was caught in a cupboard with Violet Keppel, daughter of the late King’s mistress - it was not his first rodeo. It was possibly such liaisons that inspired a pantomime he wrote for the regiment on returning to South Africa, namely: ‘The Wicked Count ... To Say Nothing of the Countess’ - ‘It is terribly improper and I shall probably lose my commission over it, but the men laugh so much while they are doing it that I think it will have a great success.’

Into Battle - France and Flanders 1914 - War Poet - D.S.O.

The 1st Royal Dragoons having returned to England from South Africa in September 1914, the regiment was embarked for France early in the following month, as part of the 3rd Cavalry Division, IV Corps, B.E.F., and was quickly in action in the first battle of Ypres - fighting in an infantry role near the Menin Road. Of his first experience of combat, Grenfell stated in a letter home:

‘I was pleased with my troop under bad fire. They used the most awful language, talking quite quietly and laughing all the time, even after the men were knocked over within a yard of them. I longed to be able to say that I liked it, after all one has heard about being under fire for the first time. But it is beastly. I pretended to myself for a bit that I liked it, but it was no good. But when one acknowledged that it was beastly, one became all right again and cool ... I adore war. It is like a big picnic without the objectlessness of a picnic. I’ve never been so well or so happy. Nobody grumbles at one for being dirty. I’ve only had my boots off once in the last 10 days, and only washed twice. We are up standing to our rifles at 5 a.m. when doing this infantry work, and saddled up at 4.30 a.m. when with our horses ... ’

In November, as cited above, he won the D.S.O. for a daring reconnaissance behind enemy lines, an incident which was actually prompted by enemy sniping. A fellow officer takes up the story:

‘We were in the trenches on a 48 hours’ turn of duty, and where we were, in a wood less than a hundred yards from the German trenches, we were very much bothered by snipers, who were doing a lot of damage. The day before yesterday Julian crept through the undergrowth right up to one of the German trenches and shot one of them dead through his own loophole. Yesterday he crawled out in the same direction and found the trench evacuated, so he crept on some little way beyond. He put two more Germans in the bag, and then came back with the most useful information that the Germans were advancing. Within half an hour they attacked the line very heavily, and were repulsed with great loss. Both acts were not only extremely plucky, but showed great resource and presence of mind, not to say cunning. I have reported the matter to the Colonel, who will send it on. He is very well and fit and cheery, in spite of many unpleasant conditions. I won’t let him do anything too rash, but so far he has shown that he is quite capable of looking after himself, and more than a match for a whole lot of damned Germans.’

Grenfell’s own account follows:

‘They told me to take a section with me, and I said I would sooner cut my throat and have done with it. So they let me go alone. Off I crawled through sodden clay and trenches, going about a yard a minute, and listening and looking as I thought it was not possible to look and listen. I went out to the right of our lines, where the 10th were, and where the Germans were nearest. I took about thirty minutes to do thirty yards; then I saw the Hun trench, and I waited there a long time, but could see or hear nothing. It was about ten yards from me. Then I heard some Germans talking, and saw one put his head up over some bushes, about ten yards behind the trench. I could not get a shot at him; I was too low down, and of course I could not get up. So I crawled on again very slowly to the parapet of their trench. It was very exciting. I was not sure that there might not have been someone there, or a little further along the trench. I peeped through their loophole and saw nobody in the trench. Then the German behind put his head up again. He was laughing and talking; I saw his teeth glistening against my fore-sight, and I pulled the trigger very slowly. He just grunted and crumpled up. The others got up and whispered to each other. I do not know which were most frightened, them or me. I think there were four or five of them. They could not trace the shot; I was flat behind their parapet and hidden. I just had the nerve not to move a muscle and stay there. My heart was fairly hammering. They did not come forward and I could not see them, as they were behind some bushes and trees, so I crept back inch by inch. I went out again in the afternoon, in front of our bit of the line. About sixty yards off I found their trench again, empty again. I waited there for an hour, but saw nobody. Then I went back, because I did not want to get inside some of their patrols who might have been placed forward. I reported the trench empty.

The next day, just before dawn, I crawled out there again and found it empty again. Then a single German came through the woods towards the trench. I saw him fifty yards off. He was coming along, upright and careless, making a great noise. I heard him before I saw him. I let him get within twenty-five yards, and shot him in the heart. He never made a sound. Nothing for ten minutes, and then there was a noise and talking, and a lot of them came along through the wood behind the trench about forty yards from me. I counted about twenty, and there were more coming. They halted in front, and I picked out the one I thought was the officer, or sergeant. He stood facing the other way, and I had a steady shot at him behind the shoulders. He went down, and that was all I saw. I went back at a sort of galloping crawl to our lines and sent a message to the 10th that the Germans were moving up their way in some numbers. Half an hour afterwards they attacked the 10th and our right in massed formation, advancing slowly to within ten yards of the trenches. We simply mowed them down. It was rather horrible. I was too far to the left. They did not attack our part of the line, but the 10th told me in the evening that they counted 200 dead in a little bit of the line, and the 10th and us only lost ten. They have made quite a ridiculous fuss about me stalking, and getting the message through. I believe they are going to send me up to our General, and all sorts. It was only up to someone to do it, instead of leaving it all to the Germans, and losing two officers a day through snipers. All our men have started it now. It is the popular amusement.’

It was about this time that Grenfell penned a satirical poem taking a gentle swipe at his military seniors, A Prayer for Those on the Staff - an indication of where his poetry may have led but for his early demise, and accordingly ground upon which to defend his reputation versus the harder-hitting poets that followed him.

Returning home on leave in January 1915, the same month in which the award of his D.S.O. was announced (in addition to a mention in despatches) Grenfell had his photograph taken in London wearing the new riband alongside that of his Coronation Medal 1902, the latter awarded for his services as a Page.

Mortally wounded

Rejoining his regiment after leave, but having visited his sister Monica at work as a Red Cross nurse at Wimereux en-route, Grenfell moved up towards the front line, near Poperinghe, in late April. In his diary entry on the 29th, he wrote:

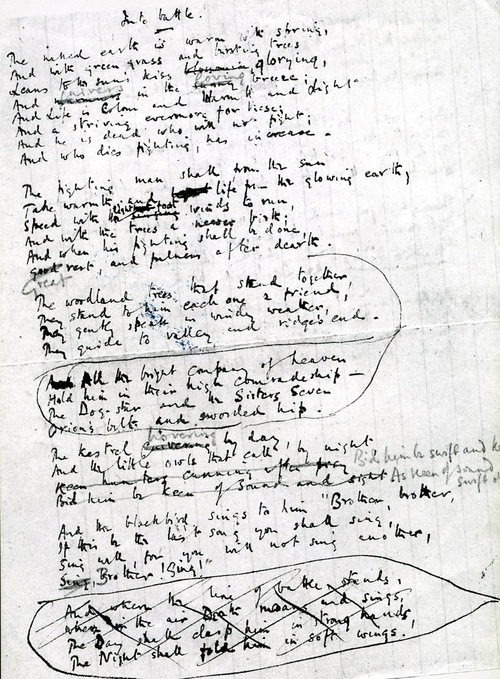

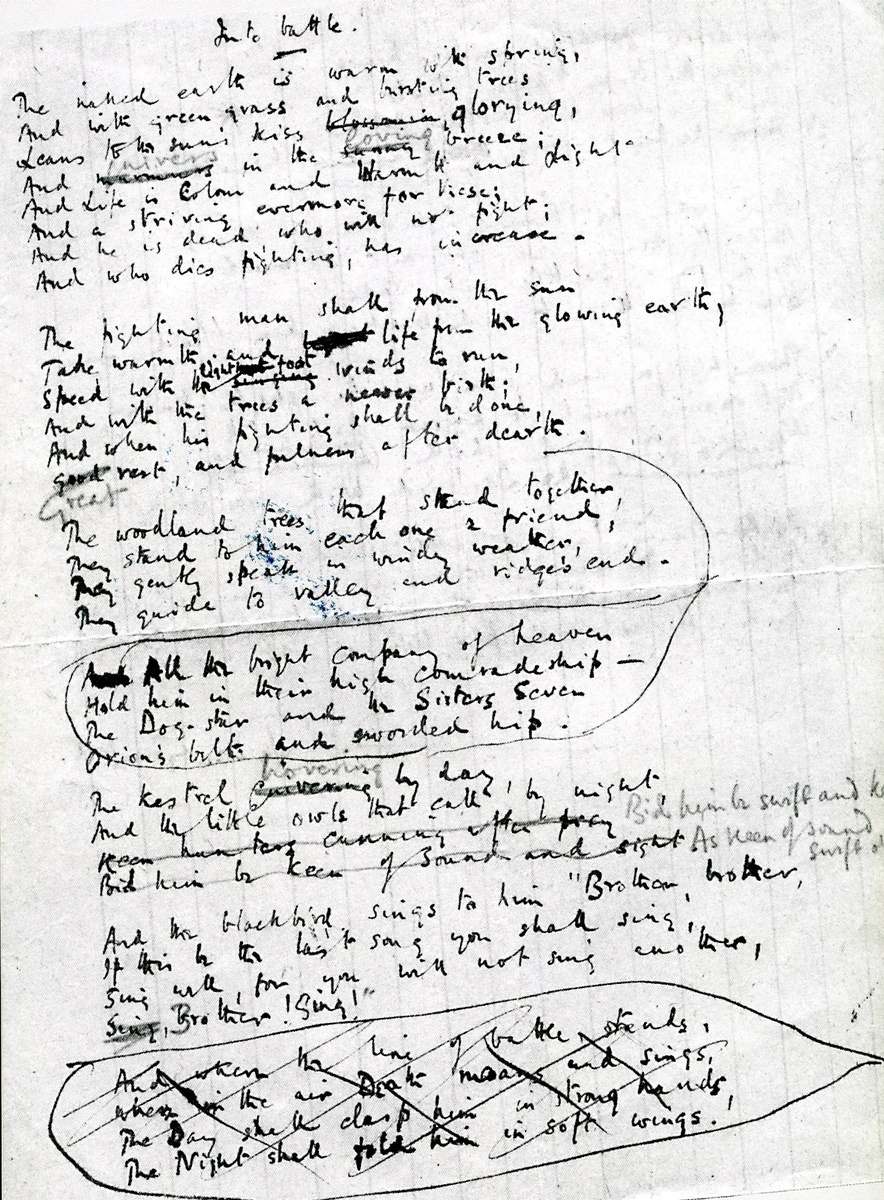

‘Moved off 8 a.m. towards Pop. Brigade rested in field. Rested all day and got back to our farm at 7.30 p.m. Pork chops for dinner. Wonderful sunny lazy days - but longing to be up and doing something. Slept out. Wrote poem - Into Battle.’

And he sent the poem to his mother, telling her to forward it to The Times if she wished - little knowing that it would eventually appear in print the day his death was announced in the following month:

'The naked earth is warm with spring,

And with green grass and bursting trees

Leans to the sun's gaze glorying,

And quivers in the sunny breeze;

And Life is Colour and Warmth and Light,

And a striving evermore for these;

And he is dead who will not fight;

And who dies fighting has increase.

The fighting man shall from the sun

Take warmth, and life from the glowing earth;

Speed with the light-foot winds to run,

And with the trees to newer birth;

And find, when fighting shall be done,

Great rest and fullness after death.

All the bright company of Heaven

Hold him in their high comradeship,

The Dog Star, and the Sisters Seven,

Orion's Belt and sworded hip.

The woodland trees that stand together,

They stand to him each one a friend,

They gently speak in the windy weather,

They guide to valley and ridges' end.

The kestrel hovering by day

And the little owls that call by night,

Bid him be swift and keen as they,

As keen of ear, as swift of sight.

The blackbird sings to him,

“Brother, brother,

If this be the last song you shall sing,

Sing well, for you may not sing another;

Brother, sing.”

In dreary, doubtful, wailing hours,

Before the brazen frenzy starts,

The horses show him nobler powers;

O patient eyes, courageous hearts!

And when the burning moment breaks,

And all things else are out of mind,

And only Joy of Battle takes

Him by the throat, and makes him blind

Through joy and blindness he shall know,

Not caring much to know, that still

Nor lead nor steel shall reach him, so

That it be not the Destined Will.

The thundering line of battle stands,

And in the air Death moans and sings;

But Day shall clasp him with strong hands,

And Night shall fold him in soft wings.'

A fortnight later, on 13 May 1915, Grenfell was wounded in the head by shrapnel. The V.C. & D.S.O. takes up the story:

‘On the previous evening he was with his regiment about 500 yards behind the front line, near the Ypres-Menin Road, in support of an attack on the German trenches running south from Hooge Lake. The Royals were behind a small hill which Julian afterwards called the little hill of death. Early in the morning the Germans heavily bombarded this hill, and Julian Grenfell went to the look-out post and was knocked over by a shell which merely bruised him. He went down again and reported his observations, and then volunteered to get through with a message to the Somerset Yeomanry in the front line, which he successfully accomplished under very heavy fire. When he returned he went up the hill with his General and a shell burst four yards away, knocking them both down and wounding Julian Grenfell in the head. He said: “Go down, sir. Don't bother about me. I'm done.” The General helped to carry him down, and was wounded while doing so. Julian said afterwards to a brother officer: “Do you know, I think I shall die,” and when he was contradicted, remarked: “Well, you see if I don't.” He was carried to the clearing station, and asked there whether he was going to die, adding: “I only want to know; I am not in the least afraid.” He was then taken to the hospital at Boulogne, and his sister came from Wimereux to nurse him, and his parents were both with him. When the surgeon asked him how long he had been unconscious after he was hit, Julian said: “I was up before the count.” ’

In point of fact a shell splinter had penetrated Grenfell’s skull by an inch and half, causing brain damage and, following two operations, he said goodbye to gathered family and friends - ‘seeing a shaft of sunlight falling across his feet, he murmured “Phoebus Apollo,” the name of the sun god of classical mythology and, apart from his father’s name, these were his last words. He died on the afternoon of the 26 May and was buried in the military cemetery at Boulogne.

Lieutenant-Colonel Maclachlan, his C.O., afterwards wrote:

‘Julian set an example of light-hearted courage which is famous all through the Army in France, and has stood out even above the lost lion-hearted.’

It is said that when Kitchener, a family friend, heard of Grenfell’s death, he lost his composure and had to leave his desk; among the mass of letters sympathy received by Lord and Lady Desborough was a message from Winston Churchill, who said ‘He was all that you could have desired and all that our race needs to keep its honour fair and bright.’

His poem Into Battle appeared in The Times on 28 May and quickly attracted critical acclaim, his old Professor of English Literature at Oxford writing, ‘I don't know if you really know that Julian's poem is one of the swell things in English literature. It is safe for ever; I know it by heart, and I never learned it. It has that queer property which only the best poems have, that a good many of the lines have more meaning than there is any need for, so that new things keep turning up in it.’

In fact it became a source of inspiration to many young men in those early stages of the war and his place in the ranks of the Great War poets was assured.

Subject to 20% VAT on Buyer’s Premium. For more information please view Terms and Conditions for Buyers.

Sold for

£9,500

Starting price

£9500