Auction: 22003 - Orders, Decorations and Medals

Lot: 401

'For an instant of time, nothing happened. Then Siemon, watching from U-334, saw a pillar of smoke about 200 feet high billow up, preceded by a blinding blue flash. The heavy naval steam launch which had been strapped in a cradle on top of No. 2 hatch was picked up bodily by the explosion and hurled a quarter of a mile across the sea.

The ship broke in two, and the bows sank almost at once. The air was filled with the terrible sound of the heavy cargo - the Churchill tanks, anti-aircraft guns, and trucks - tearing loose in the holds, and the groaning of the ship's members under the unintended strain. Then the stern section slid under the sea with a roar, leaving only the barrage balloon, which had been stowed on the after deck, floating on the sea for a few seconds as the cable paid out from the ship foundering beneath it. Then that too was plucked beneath the waves, as though by an invisible hand. Ninety seconds had passed since Hilmar Siemon had fired his third torpedo.'

The fate of the cargo steamer Earlston, as described by David Irving in The Destruction of PQ 17.

The important Second World War 'PQ-17' M.B.E. and Lloyd's Medal for Bravery at Sea group of eight awarded to Second Officer D. M. L. Evans, Merchant Navy, who somehow survived the loss of the S.S. Earlston in the freezing waters of the Barents Sea on 5 July 1942

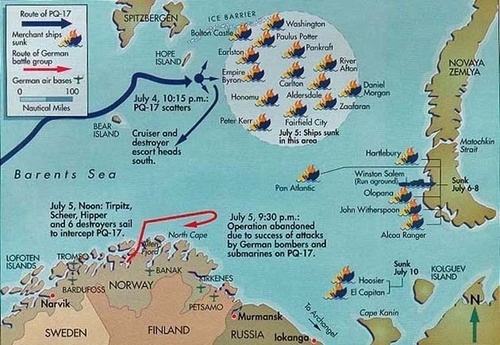

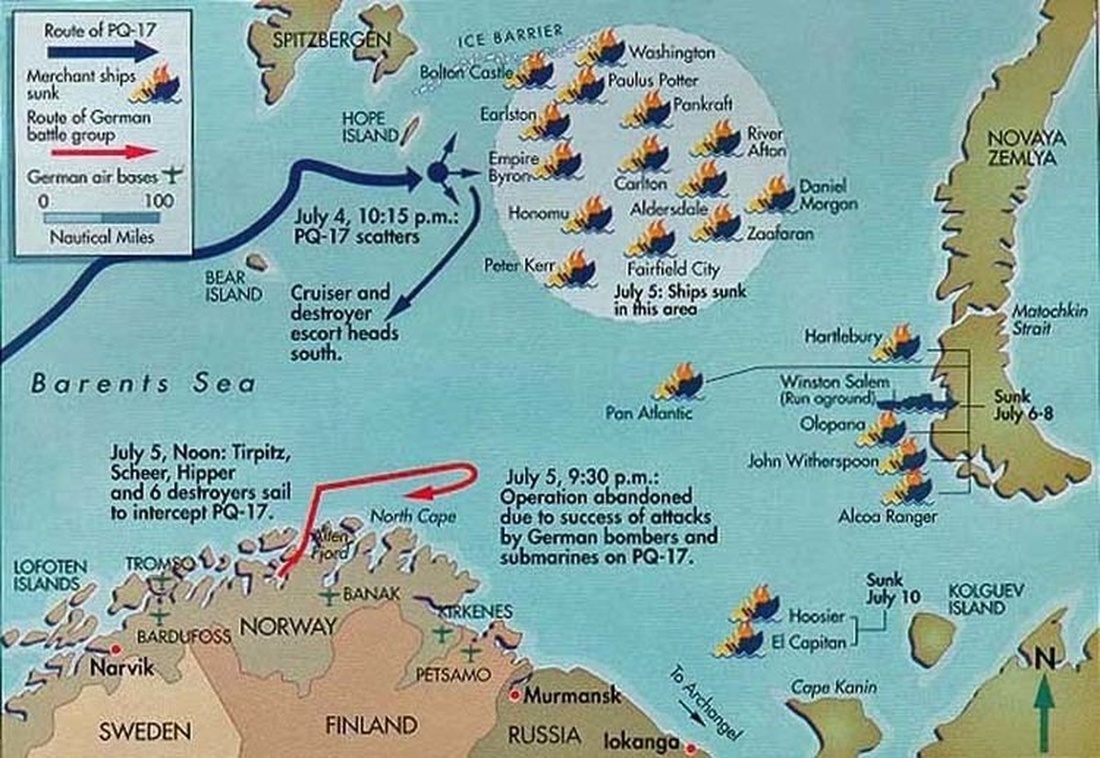

Following the infamous order for the convoy to scatter, Donitz's wolf packs moved in for the kill and sank no less than 24 merchantmen. In fact, such was the resultant loss of life that Winston Churchill was moved to describe the massacre 'as one of the most melancholy naval episodes in the whole of the war'

Those losses included 26 men embarked in the Earlston - a victim of the Luftwaffe and the U-334 - but a good number survived her loss, largely owing to the gallant example set by Evans, who took charge of one of the ship's boats and navigated it to land: that nightmare journey - in a crowded, open boat - took seven days, towards the end of which he collapsed 'prostrate with illness'

The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire (M.B.E.), Civil Division, Member's 2nd type badge, with its Royal Mint case of issue; 1939-45 Star; Atlantic Star; Africa Star; Italy Star; War Medal 1939-45; Lloyd's Medal for Bravery at Sea, silver (Second Officer D. M. L. Evans, S.S. "Earlston", 5th July 1942), with its fitted case of issue; U.S.S.R., 40th Anniversary Medal 1941-45, the campaign medals with their original O.H.M.S. card forwarding box addressed to 'Mr. D. M. L. Evans, M.B.E.' at a Cardiff address, generally extremely fine (8)

M.B.E. London Gazette 6 October 1942:

'When his ship was sunk, the Second Officer [Evans] took charge of the navigation of a crowded boat and brought her people to land after seven days. When he himself was prostrate with illness, the handling of the craft was carried on by Able Seamen Folwell, Holman, and Hooper. It was largely due to their untiring efforts and example that the lives of the 33 survivors were saved.'

Lloyd's Medal for Bravery at Sea Lloyd's List and Shipping Gazette 31 August 1943.

David Meredith Lyon Evans was born at St. Dogmaels in Pembrokeshire on 6 February 1917, the scion of a seafaring family. His father commenced his career as a boy seaman in the Edwardian era and was still serving as a Chief Officer in the Second World War.

Young David entered the Merchant Navy in early 1932 and was serving as an Able Seaman in the S.S. Trevoriant on the outbreak of hostilities in September 1939. In January 1940, having qualified as a 3rd Mate, he joined the cargo steamer Amicus, but he had moved to a new appointment by the end of the year, for the Amicus was torpedoed and sunk by the Italian submarine Apino Attilio Bagolini on 19 December 1940, with the loss of her entire crew.

By the summer of 1942, Evans had been advanced to Second Officer and was serving aboard the S.S. Earlston, and it was in this capacity that he joined PQ-17 on the Arctic run.

PQ-17

The fate of PQ-17 has been graphically described by such historians as David Irving (in The Destruction of Convoy PQ. 17), and by Richard Woodman (in Arctic Convoys), but in terms of more immediate statistics it is worth recording that the convoy originally assembled at Reykjavik on 27 June 1942, a formidable gathering that in addition to the naval escort comprised 22 American, eight British, two Russian, two Panamanian and one Dutch merchantmen.

In their holds they carried sufficient supplies to re-arm a good portion of the Stalin's forces - 297 aircraft, 594 tanks, 4246 military vehicles and over 150,000 tons of other vital military stores and cargo: but most of this equipment never reached Russia, for just a few days later, following Sir Dudley Pound's fateful order for the convoy to scatter, no less that 24 of these merchantmen were lost to enemy action.

Facing off the U-boats

For her own part, the cargo steamer Earlston, commanded by Master Hilmar Stenwick, D.S.C., had embarked over 2,000 tons of military stores, in addition to 195 vehicles, 33 aircraft and a steam launch as deck cargo.

The convoy was quickly picked-up by German reconnaissance and a spate of aircraft and U-boat attacks commenced on 1 July 1942. Earlston met her end on the 5th, after being attacked and badly damaged by Ju. 88s of III/KG 30 operating out of Banak in Norway.

David Irving takes up the story in his definitive history, The Destruction of PQ 17:

'Towards three o'clock a British merchant ship confronted with a similar kind of situation reacted very differently … her First Officer, Mr. Hawtry Benson, sighted what he took to be a 'growler' - a small grey iceberg almost completely submerged. What was remarkable was that the 'iceberg' seemed to be steadily and almost imperceptibly overhauling them. The U-boat's conning tower had been painted white on top, and as it drew nearer Earlston's Master, Captain Hilmar Stenwick, could confirm Benson's suspicions. Visibility was very good, without a trace of fog in which they might hide their naked merchantmen. He gave his helmsman a new course to steer, and a signal was transmitted, 'SS Earlston in action with U-boat', giving their position.

'In action' because the naval gun crew manning the low-angle 4-inch gun on Earlston's poop deck had already opened fire on the submarine. The submarine was by now some 8,000 yards away, but closing on them at superior speed now that its commander recognized that he had been sighted. On the surface, the U-boat had greater speed than the merchant ship. Captain Stenwick ordered more speed, nevertheless, and all the off duty firemen were ordered down into the stokehold to double-bank the firemen already on watch.

The ship began to vibrate strongly under the straining engines as they gradually picked up speed. A new signal was transmitted: 'SOS, SOS, SOS. SS Earlston taking action against submarine, steering 207º, submarine following. 3.09 p.m.' Their gun had fired several rounds at the U-boat, and the rounds were bursting successively closer to the conning-tower; the submarine began to submerge, and then vanished completely, still out of torpedo range. As long as it remained submerged, it had no hope of overhauling the speeding vessel. Of all the merchantmen in the convoy, this British vessel was the only one to keep its nerve in the face of a submarine attack and use the gun for the purpose for which it had been provided.'

Arrival of the Luftwaffe

Yet Earlston's fate was to be sealed in the late afternoon. Irving continues:

'Three German submarines were still trailing the British Earlston, some way to the west of Zaafaran's grave. They were keeping a wary distance between themselves and the Briton, who had already discomfited one U-boat with her anti-submarine gun.

From the merchantman's bridge, the First Officer had seen the bombing of Peter Kerr to the south, and they had shaped a more northerly course since then. In her holds were several hundred tons of explosives, and crates of ammunition as well.

She survived until late afternoon, when a flight of returning Junkers 88s spotted her, and attacked from astern. Three bombs hit the sea off the ship's bows, throwing up a wall of water into which the Earlston plunged. She shook herself free, and Chief Officer Benson struggled waist-deep through the water to inspect the damage; he shouted to the Captain that the plates would hold, and had begun making his way back to the bridge when a lone Junkers 88 roared in at bridge height from the starboard bow, dropping a single bomb into the sea just by the vessel's port side. The engines stopped, and the ship slowed to a standstill. The three submarines stopped too, and waited.

Captain Stenwick's wireless operator broadcast an 'air attack' distress signal, and he ordered his crew to abandon ship. As the crew pulled away in the two lifeboats, they could see steam pouring out of the engine-room ventilators and the ship settling lower in the water. Scarcely had they put a quarter of a mile between themselves and the ship, fearing that the explosives in No. 2 hold would blow up, than two submarines surfaced on Earlston's starboard bow within a few moments of each other - U-334 and, most probably, U-456 who three hours before had torpedoed the American Honomu.

A short while later, yet a third submarine surfaced, not far from the other two. Commander Siemon's U-334 began to close in fast on the helpless vessel. When she was still 1,300 yards away, he fired tube II at her, aiming at the freighter's empty bridge. The torpedo struck abreast the after mast; the ship listed slightly, but stayed well afloat. Siemon fired tube III, but the torpedo missed; he fired tube IV, his submarine now barely seven hundred yards away.

The torpedo sped towards the British ship, and the seamen in their lifeboats saw with trepidation that it was heading straight for No. 2 hold. The white trail of bubbles extended to the Earlston's flanks abreast the foremast, and stopped.

For an instant of time, nothing happened. Then Siemon, watching from U-334, saw a pillar of smoke about 200 feet high billow up, preceded by a blinding blue flash. The heavy naval steam launch which had been strapped in a cradle on top of No. 2 hatch was picked up bodily by the explosion and hurled a quarter of a mile across the sea.

The ship broke in two, and the bows sank almost at once. The air was filled with the terrible sound of the heavy cargo - the Churchill tanks, anti-aircraft guns, and trucks - tearing loose in the holds, and the groaning of the ship's members under the unintended strain. Then the stern section slid under the sea with a roar, leaving only the barrage balloon, which had been stowed on the after deck, floating on the sea for a few seconds as the cable paid out from the ship foundering beneath it. Then that too was plucked beneath the waves, as though by an invisible hand. Ninety seconds had passed since Hilmar Siemon had fired his third torpedo.

The British ship's Master, Captain Hilmar Stenwick, was ordered on to U-334's foredeck. He asked what would become of his ship's lifeboats, but received no satisfactory reply. He disappeared into the bowels of the submarine. The three U-boats moved off on the surface, their officers shouting congratulations to each other on their good hunting so far. The latest victory was signalled to Admiral Hubert Schmundt in Narvik.'

As it transpired, U-334's moment of victory was short-lived. Irving continues:

'Within moments, a German sailor in the conning-tower of U-334 shouted that an aircraft was coming in to attack them. It passed low overhead and released two bombs which detonated not far from the starboard side of the U-boat; but the attack had not come so fast that the submarine officers were not able to identify the attacking aircraft - it was a Junkers 88, a German plane. The U-boat trembled in the blast, and everything loose flew out of its supports; the floor-plates were torn up, the diesel engines were unseated and one ballast tank fractured. A fine spray of water entered the boat, and the lights went out. A voice in the conning-tower yelled, 'Abandon ship, the boat is sinking!' The aircraft returned, and machine-gunned the submarine from very low altitude - 'fortunately,' one of the submarine crew later said, 'she had no more bombs left'. Then the plane left them, leaving the submarine to right herself as best she could. U-334's steering gear had been jammed, and she was unable to submerge. Not far away, Commander Brandenburg's U-457 also reported that all manner of aircraft were executing bombing-runs on his submarine.

Lieutenant-Commander Siemon wirelessed details to Schmundt, and recommended that U-456, who was with him and had currently lost contact with the enemy, should be detached from the operation to escort U-334 back to Kirkenes naval base. Schmundt agreed, and ordered the two U-boats to observe wireless silence all the way …'

Meanwhile, as cited in the London Gazette of 6 October 1942, David Evans took charge of one of Earlston's boats, and undertook a brutally cold week-long voyage to safety. But by the time land had been reached, he was 'prostrate with illness.' He was awarded the M.B.E. and the Lloyd's Medal for Bravery at Sea.

As related by David Irving, the fate of Earlston's second boat was less happy:

'The other [boat] had rowed for ten days and nights towards Russia, on rations badly diminished by the fact that Clydeside dock-workers had broken open the lifeboat's lockers and stolen most of their contents. After ten days' rowing, sustained only by half a cupful of water in the morning, and half a cupful mixed with condensed milk at midday, the British seamen had come ashore, delirious from hunger and thirst, only to find themselves in German-occupied Norway, ten miles to the east of North Cape. Too weak to weep, the twenty-six angry seamen had been hauled off to spend the rest of the war in a German prison camp.'

An interview with Andrew Watt, who survived the Earlston's loss and was in Evans's open boat, forms part of the Imperial War Museum's sound archive (Catalogue No. 11759).

In January 2014, the hour-long BBC Two documentary PQ17: An Arctic Convoy Disaster, written and narrated by Jeremy Clarkson, retold the story of the convoy with first-hand testimony from the men who served. It is recommended:

https://www.amazon.co.uk/PQ-17-Arctic-Convoy-Disaster/dp/B00JAI29AM

Postscript

Evans remained actively employed in the Merchant Navy after the war and he died at sea - aboard the oil tanker Border Chieftain - on 17 June 1965.

Sold with an interesting quantity of nursing badges awarded to his wife, Mary, who served as a Theatre Sister at Carmarthen County Infirmary during the war. She had earlier served at Cardiff Royal Infirmary.

Subject to 20% VAT on Buyer’s Premium. For more information please view Terms and Conditions for Buyers.

Sold for

£2,700

Starting price

£1400