Auction: 22003 - Orders, Decorations and Medals

Lot: 395

THE FAR EAST 1941-42

'After an exhaustive but - as it turned out - ineffective medical examination, the prisoners were loaded on the 27th September into lighters from the pier at the corner of Shamshuipo camp, and taken out to a freighter of some 7000 tons, the Lisbon Maru, under the command of Captain Kyoda Shigaru, where they were accommodated in three holds.

In No. 1 hold, nearest the bows, were the Royal Navy under the command of Lieutenant J. T. Pollock. In No. 2 hold, just in front of the bridge, were the 2nd Battalion of the Royal Scots, 1st Battalion Middlesex Regiment, and some smaller units, all under Lieutenant-Colonel Stewart. And in No. 3 hold, just behind the bridge, were the Royal Artillery under Major Pitt. Conditions were very crowded indeed, all men lying shoulder to shoulder on the floor of the hold, or on platforms erected at various heights. The officers on a small tween-deck half-way up the hold were similarly crowded.

There was not sufficient room for the men to be able to lie down all at the same time so sleeping was to be achieved by rota … The latrines consisted of wooden hutches hanging over the side, too few for the numbers on board. Within a very short time after boarding, the stench of sweating men and excreta became an intolerable burden, so the Japanese allowed sections of prisoners on deck in rota for prescribed periods of time.

Also on board were 778 Japanese soldiers, who occupied most of the deck space forward, with a guard of 25 under Lieutenant Hideo Wada. For the first few days, the voyage had so far been uneventful apart from the natural grumbling of the men, who so far had not been able to have much sleep, due to the heat, the oppressive atmosphere, the stench and the rolling movements of the ship. About half the men were issued with kapok life belts. At the subsequent War Crimes trial interpreter Niimori claimed that every man had a life belt, which he checked at each roll call.

There were four lifeboats and six life rafts and, according to the Captain, it was decided that the four lifeboats and four of the rafts should be set aside for the Japanese if required, leaving the remaining two life rafts for the 1800 plus P.O.W.s …'

See: http://www.hongkongescape.org/Lisbon-Maru.htm

An emotive Great War campaign group of four awarded to Able Seaman V. V. Stainer, Royal Navy

Earlier a survivor of the loss of H.M.S. Triumph in June 1915, he was recalled to active service on the renewal of hostilities in September 1939 and embarked for Hong Kong, where he joined Tamar's Controlled Mining Party

Taken P.O.W. at the fall of the colony in December 1941, he was among those embarked for Japan in the 'hell ship' Lisbon Maru in September 1942, in which he endured shocking conditions for four days until she was torpedoed by the U.S. submarine Grouper: if conditions up until that point had been shocking, what followed became the subject of a war crimes trial …

https://www.bbc.co.uk/history/ww2peopleswar/stories/23/a4105423.shtml

1914-15 Star (J. 2583 V. V. Stainer, A.B., R.N.); British War and Victory Medals (J. 2583 V. V. Stainer, A.B., R.N.); Royal Navy L.S. & G.C., G.V.R., 2nd issue (J. 2583 V. V. Stainer, A.B., H.M.S. Victory), mounted as worn, polished, generally fine (4)

Victor Vulcan Stainer was born in Portsmouth, Hampshire on 31 May 1892 and entered the Royal Navy as a Boy 2nd Class in September 1908.

The Great War

At the time of the outbreak of hostilities in August 1914, he was serving as an Able Seaman in H.M.S. Triumph, and he remained likewise employed up until her loss in June 1915, when she was torpedoed off Gaba Tepe by the U-21 on 25 May 1915. The impact of the torpedo caused a massive explosion and she capsized in ten minutes, with a loss of three officers and 75 ratings.

Stainer, who was among the survivors, would earlier have seen action in Triumph off Tsingtao in September 1914, and at several bombardments carried out in the Dardanelles in early 1915.

He subsequently served in the cruiser Proserpine from July to November 1915 and in the destroyer Plucky from July 1916 to October 1918. Awarded his L.S. & G.C. Medal in August 1925, he also served on the China Station in the river gunboat Peterel from May 1927 to October 1929, and was pensioned ashore in May 1932.

Hong Kong - FEPOW

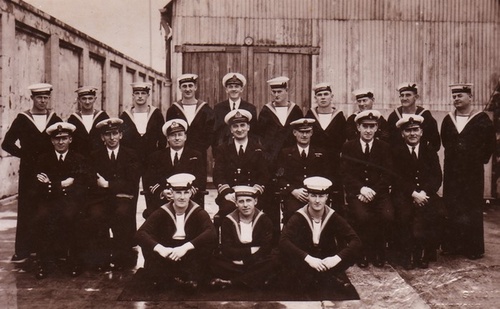

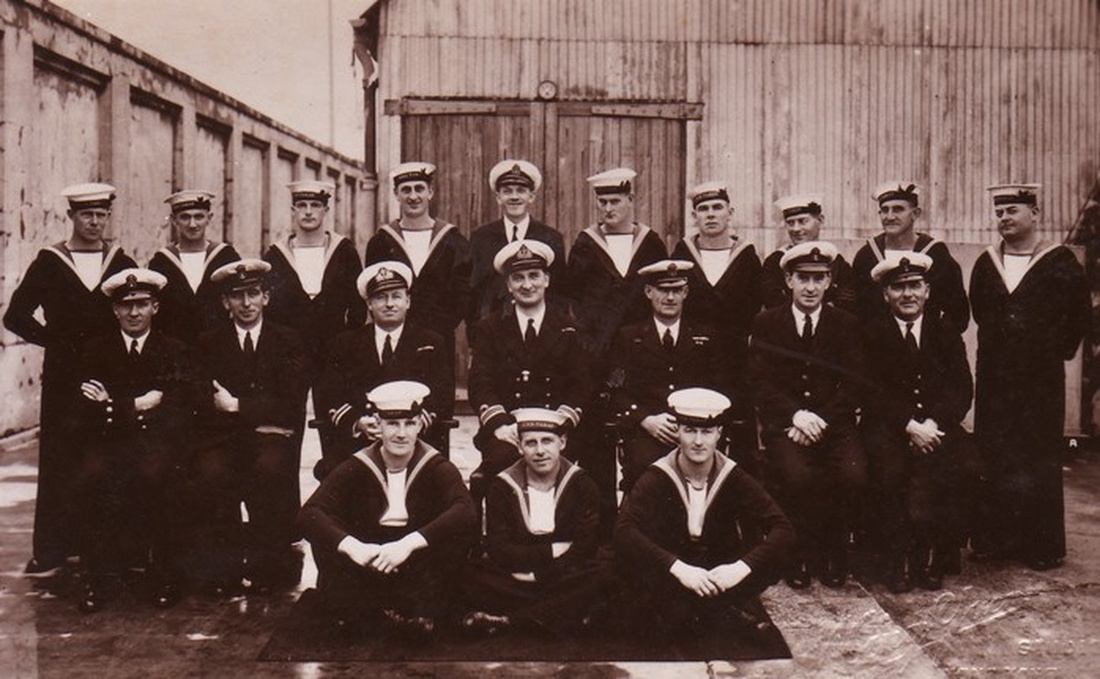

Recalled in the lead-up to the renewal of hostilities, he was embarked for Hong Kong in August 1939, where he joined Tamar's Controlled Mining Party (C.M.P.) as an Able Seaman, charged with installing defensive minefields in the colony's waters.

Sadly, to no avail, for those duties came to an end on 25 December 1941, close to his fiftieth birthday, when he was taken P.O.W. by the Japanese. As verified by official records, he was subsequently among those embarked for Japan in the Lisbon Maru in September 1942.

Loss of the "Lisbon Maru"

The Lisbon Maru sailed from Hong Kong on 27 September 1942, bound for Shanghai and labour camps on the Japanese coast. She was armed, and carried 1,816 British prisoners of war, 778 Japanese troops and a further guard of 25 men for the prisoners. There was nothing that identified her cargo as prisoners of war.

379 Royal Navy personnel were accommodated in No. 1 Hold at the front of the ship. A further 1,077 troops were crammed into No. 2 Hold, forward of the bridge, including the Senior British Officer on board, Lieutenant-Colonel H. W. M. Stewart, Commanding Officer of the 1st Battalion, Middlesex Regiment, whilst 380 men of the Royal Artillery were placed in the stern. Conditions were appalling, made worse by a lack of sanitation and the sea conditions. At the base of No. 2 Hold, Dennis Morley, a 22-year-old Private in the Royal Scots Regiment, later recalled being 'showered by the diarrhoea of sick soldiers above him … swimming in excreta, virtually.'

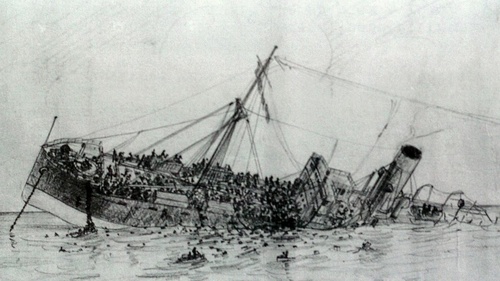

On 1 October 1942, the American submarine Grouper fired six torpedoes at the Lisbon Maru off Dongfushan in the Zhoushan Archipelago, to the south of Shanghai. Five of the unreliable Mark 14 'fish' either passed under the target or failed to detonate, but one exploded against the stern bringing the ship to a standstill. Grouper immediately came under retaliatory attack from enemy patrol boats and aircraft and departed the scene, enabling the Japanese troops aboard the Lisbon Maru to be taken off the stricken vessel. As they departed, they battened down the hatches, leaving their prisoners standing in the dark and running short of air to breathe.

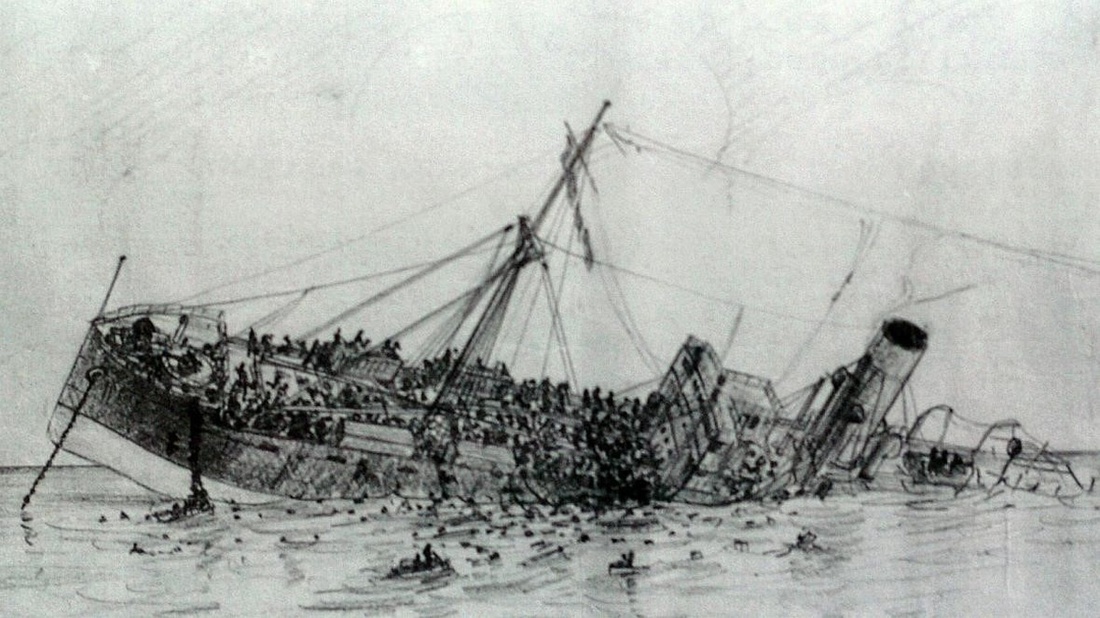

Throughout the following night the prisoners remained trapped in the holds. Messages in morse code were rapped on the bulkheads between them, and gradually the stern began to fill with water. Something urgently needed to be done to prevent the men drowning or dying of asphyxiation. As the sun began to rise on the morning of 2 October 1942, the men felt the hull give 'a sudden drunken lurch', and a frantic escape effort began. Morley describes the scenes that he witnessed:

'Well, one chap, he was in the Middlesex Regiment, he was a butcher and the Japanese allowed him this knife, which he was able to put through the planks. He got through to the canvas, eventually - the whole lot. The canvas could be lifted out of the way and the planks moved which is how we got out.

A bit of panic started because everyone was trying to rush up to this ladder and everybody was fighting to get onto this ladder. Consequently, you're getting so far up and falling down into the bottom of this hold - until this officer, Captain Cuthbertson of the Royal Scots, stopped the panic and got them to quieten down.'

This account is challenged by another which states that Lieutenant Howell managed to cut his way out of the hold using a bread knife smuggled aboard ship, but whatever the case, the first P.O.W.s to reach the deck were fired at by a few remaining Japanese guards who were quickly dispatched. Then the British began to slide off the side of the ship into the water in an attempt to get away from the vessel, but they were targeted by machine-guns from the Japanese who were watching on.

It was only when Chinese fishermen started coming to the aid of the soldiers and sailors in the water that the firing ceased and the Japanese began to gather them up as well. At the stern of the ship, men of the Royal Artillery continued to hoist themselves up a ladder which eventually broke; in one of the most harrowing scenes of the tragedy, the survivors in the water listened with horror as dozens of trapped men of the Royal Artillery went down with the ship singing 'It's a long way to Tipperary'.

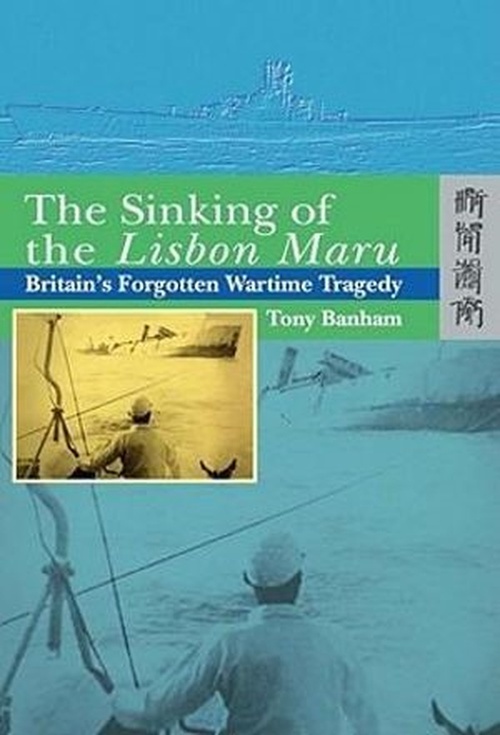

In total, 828 Prisoners of War died either aboard ship or in the waters around the vessel (The Sinking of the Lisbon Maru, Britain's Forgotten Wartime Tragedy, refers). Especially tragic was the fact that the ship had been sunk by an American submarine, whose crew were completely unaware that there were Allies aboard until they picked up a radio signal several days later. Of the survivors, only 748 returned to the U.K. alive following the cessation of hostilities.

Recommended reading:

Having survived the loss of the Lisbon Maru, Stainer and his fellow captives endured further trials:

'35 of the prisoners who were seriously ill were left in Shanghai and the remainder were then loaded in the holds of a Japanese transport, the Shensei Maru, in conditions similar to those on the Lisbon Maru. Dysentery and diphtheria were now rife and the men in poor shape, five of them dying on the journey to Japan. The ship docked at Moji on 10 October, where 36 of the worst cases of dysentery were removed to hospital. The remaining prisoners were directed into two groups, the larger, consisting of about 500 men, destined for Kobe, and the remainder for Osaka.

Press representatives spoke to some of the prisoners, who had been warned not to speak freely about their experiences because of inevitable reprisals, for it was obvious that the Japanese would not tolerate an accurate account of the matter. This reticence enabled the Japanese to claim that: 'with one voice and in the highest possible terms these surviving British prisoners referred to the strength and warm heartedness of the Imperial Forces, and lauded the gallantry of the Japanese.

To their great surprise, the prisoners were loaded on a comfortable passenger train at Moji and were provided with regular meals of excellent quantity and quality. After several hours travelling, the train stopped at a station and an announcement was made that the prisoners who were most ill would be taken off the train and sent to hospital. About 50 of the worst cases were dropped off at Kokura, where 21 of them died, and others were off-loaded at a place which was later to become well known: Hiroshima. The remaining 326 were carried on to Osaka, where they were accommodated in barracks in the middle of the town.'

https://www.ient.org.uk/index.php?page=the-sinking-of-the-lisbon-maru, refers.

Those 326 men - including Stainer - were subsequently incarcerated at Camp No. 1, Osaka, where they were used as slave labour in the loading and unloading of ships.

Given their enforced and exhausting labour, the daily rations were of little compensation:

Breakfast - Rice and soup

Lunch - Rice and seaweed, and sometimes bread

Dinner - Rice and soup, with fish every 10 days, and meat once or twice a month

Life in No. 1 Camp, Osaka is perhaps best summarised by the words of Jack Rix, a young rating of the Royal New Zealand Navy:

'While in captivity, I have had scabies, tropical ulcers, Hong Kong Dog (similar to malaria), yellow jaundice, chronic diarrhoea, dysentery 3 times, boils, ulcer in ear, broken foot, dobie rash, bronchitis, beri beri and pneumonia... I had to take the bombs, torpedoes, dive-bombers, and starvation along with the enemy, instead of being with our allies on the dealing-out side … Many times I had one foot in the grave and the other on a bar of soap and the sky was black and threatening to rain … Sometimes I nearly lost hope but always thought of … that wonderful native land, New Zealand' (his letter home after liberation, dated 23 December 1945, refers).

No doubt Victor Stainer was sustained by his hope of returning to his wife, then resident at Rose Cottage, Rake, Hampshire.

A subsequent report collated for a war crimes trial stated that all three locations of the camp were situated along the Osaka waterfront and in the midst of vital military objectives. As a result, all three were bombed, two being completely burned out and the third severely damaged.

On 2 June 1945 the P.O.W.s were transferred to Tsumori Camp and, on 10 July 1945, they were again transferred to Minato Ku in Osaka. Here they were quartered in three rooms on the second floor of a large warehouse.

Stainer was finally liberated on 2 September 1945 and, on returning to the U.K., he was released as Class 'A' in May 1946.

Postscript

A relatively recent article published on the http://www.hongkongescape.org/Lisbon-Maru.htm website, states:

'The Japanese are now sending their students and teachers from schools, colleges, and universities over here to the U.K. to be lectured and educated by former British Prisoners of War, about the atrocities committed by the Japanese Imperial Army. Here is an account by Jack Hughieson [ex-telegraphist H.M.S. Cicala and M.T.B. 08], who survived the Lisbon Maru:

"We were invited to London during July to meet up with a party of Japanese school children, university students, and teachers who were over here to obtain as much information as possible, about the atrocities meted out to Prisoners of War in the Far East during the last War. The initial program was for three days with ex-P.O.Ws giving lectures of their experiences, followed by questions from the Japanese. It was so successful it was extended several days.

Their interest in what happened during our captivity was quite overwhelming. Their determination to get the truth in every detail, taking notes for their return to their respective Schools/Universities made it all worthwhile. One of the days was spent in the Japanese Embassy, London where we discussed our treatment in the presence of the Japanese Ambassador. He introduced two former Japanese servicemen who were involved in such treatment. One, an ex-Imperial Army Officer who had served with the Japanese Imperial Army during the building of the infamous Burma Railway. The other was a Japanese ex-Naval officer, who had served in the battles around Singapore.

The atmosphere was for some time quite tense, particularly when, through an interpreter, they told their side of the story, most of which tallied up with ours. The ex-Army Officer was on his knees crying and pleading guilty and asking for forgiveness. The ex-Naval Officer spoke of the number of times he had to witness the terrible atrocities carried out by the Army as his ship handed back prisoners picked up at sea. The beatings and torture he saw as the prisoners landed on the quay side from his ship still lived with him".'

So, too, surely, with the likes of Victor Stainer.

Subject to 20% VAT on Buyer’s Premium. For more information please view Terms and Conditions for Buyers.

Sold for

£320

Starting price

£300