Auction: 22003 - Orders, Decorations and Medals

Lot: 387

'Dear Sir,

There was a bloody great bang.

I have the honour to be, Sir, your obedient Servant'.

So stated a Midshipman of H.M.S. Grenade, on being invited to recall events at Dunkirk on 29 May 1940.

A well-documented pre-war Palestine operations and Second World War campaign group of six awarded to Chief Petty Officer S. Bennion, Royal Navy, who was mentioned in despatches for his gallantry during Operation "Dynamo"

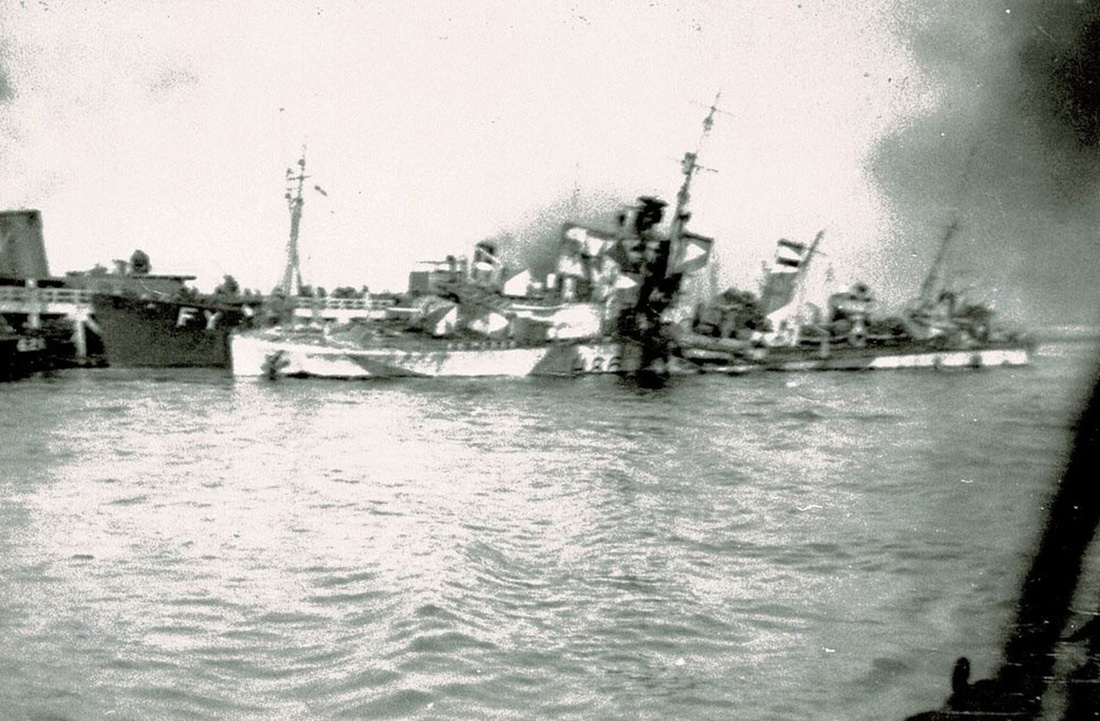

Among those fortunate to survive the loss of the destroyer H.M.S. Grenade - which ship received a direct hit at Dunkirk on 29 May 1940 - he subsequently displayed 'marked initiative and coolness' in rescuing ratings in distress in the oil covered water, before helping to bring some of them ashore and thence home in 'an old motor-boat'

Naval General Service 1915-62, 1 clasp, Palestine 1936-1939 (J. 102723 S. Bennion, P.O., R.N.); 1939-45 Star; Atlantic Star; Defence and War Medals 1939-45, with M.I.D. oak leaf; Royal Navy L.S. & G.C., G.VI.R., 1st issue (J. 102723 S. Bennion, P.O., H.M.S. Gallant), minor edge bruise to last, otherwise extremely fine (6)

Samuel Bennion was born in Boston, Lincolnshire on 14 March 1906 and entered the Royal Navy as a Boy 2nd Class in June 1921.

Subsequently awarded the Naval General Service Medal for services off Palestine as a Petty Officer in the destroyer H.M.S. Gallant, he was awarded his L.S. & G.C. Medal aboard the same ship in January 1939. One year later, he removed to the destroyer Grenade.

Dunkirk and destruction

Bombed and set on fire on 29 May 1940, the Grenade drifted across Dunkirk's harbour, grounded, and blew up. Fortuitously for posterity's sake, one of her officers, Lieutenant-Commander E. C. Peake, later left a compelling account of events:

'The morning of 29 May was beautiful, warm, with brilliant sunshine, and a flat, calm sea. On the way over, there was heavy enemy air activity. And ample evidence of their success. Wreckage, corpses. I shall never forget a red-headed woman who floated face-down. Her handbag was beside her, right on station. We arrived at Dunkirk during the forenoon and berthed at the landward end of the pier, so that other small ships such as trawlers could berth astern of us. We expected to load and get back to England as soon as possible. But for some unknown reason whilst other ships filled up with troops we were kept empty. There was a rumour that the evacuation was to be called off, and that we were being kept to take off the General Staff. We remained alongside all the afternoon whilst other ships came and went.

There was intense air activity the whole time, particularly from dive bombers ... The general level of noise was incredible - not only from gunfire and explosions but from hundreds of stray dogs which had been driven to the water-front. They were a pathetic sight. All of them were terrified. We suffered a few casualties on board during the afternoon, but no damage to the ship.

There was intense air activity the whole time, particularly from dive bombers ... The general level of noise was incredible - not only from gunfire and explosions but from hundreds of stray dogs which had been driven to the water-front. They were a pathetic sight. All of them were terrified. We suffered a few casualties on board during the afternoon, but no damage to the ship. At about 4 p.m. Stukas made a most determined attack on us and we were hit by a stick of bombs simultaneously. Two hit aft and one went straight down the foremost funnel, not touching the funnel casing and burst in Number One Boiler. I cannot remember where the fourth hit. Number One Boiler was directly below the bridge, and its bursting caused havoc on the bridge.

Onlookers ashore told me afterwards that all went up about twelve to fifteen feet. I can assure anyone that being blown up is comparatively painless. It's the coming down that hurts! As a result of the bombs, the ship was badly on fire and the engines out of action. I went round the ship to estimate the extent of the damage and reported to the captain that in my opinion, we should abandon and then cut her adrift. There was a strong tide running under the pier, and she would drift away from the pier. he agreed ... We abandoned ship and cut her adrift and, as I knew she would, she drifted to the other side of the harbour, grounded and eventually blew up ... Altogether, aboard Grenade, we had nineteen men killed and an unknown number wounded ...'

The original recommendation for Bennion's mention in despatches, which was announced in the London Gazette on 16 August 1940, states that he 'ably backed Mr. Crew, displaying marked initiative and coolness', the latter being the ship's Schoolmaster, who in turn was recommended for 'rescuing ratings in distress in the oil covered water, landing with a party of survivors in Dunkirk', where he 'took charge and eventually navigated an old motor boat back to England.' Bennion, no doubt, was with him all the way.

Subsequent career

He afterwards served at Nimrod, the Asdic training establishment at Campbeltown, Argyll, from June 1940 to April 1942, in which period he was advanced to Chief Petty Officer.

In March 1944, he was appointed a Temporary Acting Boatswain, and he appears to have ended the war with an appointment as an Asdic instructor at the Greenock shore establishment Orlando.

Sold with a quantity of original documentation and photographs, including the recipient's mention in despatches certificate, this cut down in size and mounted in a frame, with related O.H.M.S. transmission envelope; his 'On Active Service' Bible and Admiralty enclosures for his campaign medals and M.I.D. oak leaf; a photograph album containing approximately 45 black and white photographs, many with annotation, together with a group photograph including the recipient as part of the winning team in the 1-mile Whalers' Race at the Portland Regatta in 1948; and various postcard photographs.

Subject to 20% VAT on Buyer’s Premium. For more information please view Terms and Conditions for Buyers.

Sold for

£480

Starting price

£350