Auction: 22003 - Orders, Decorations and Medals

Lot: 379

23 NOVEMBER 1939: LOSS OF THE ARMED MERCHANT CRUISER "RAWALPINDI"

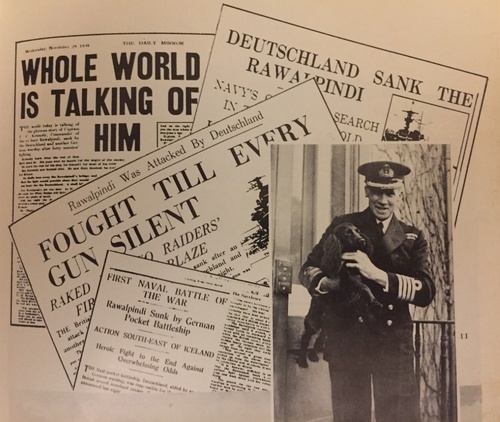

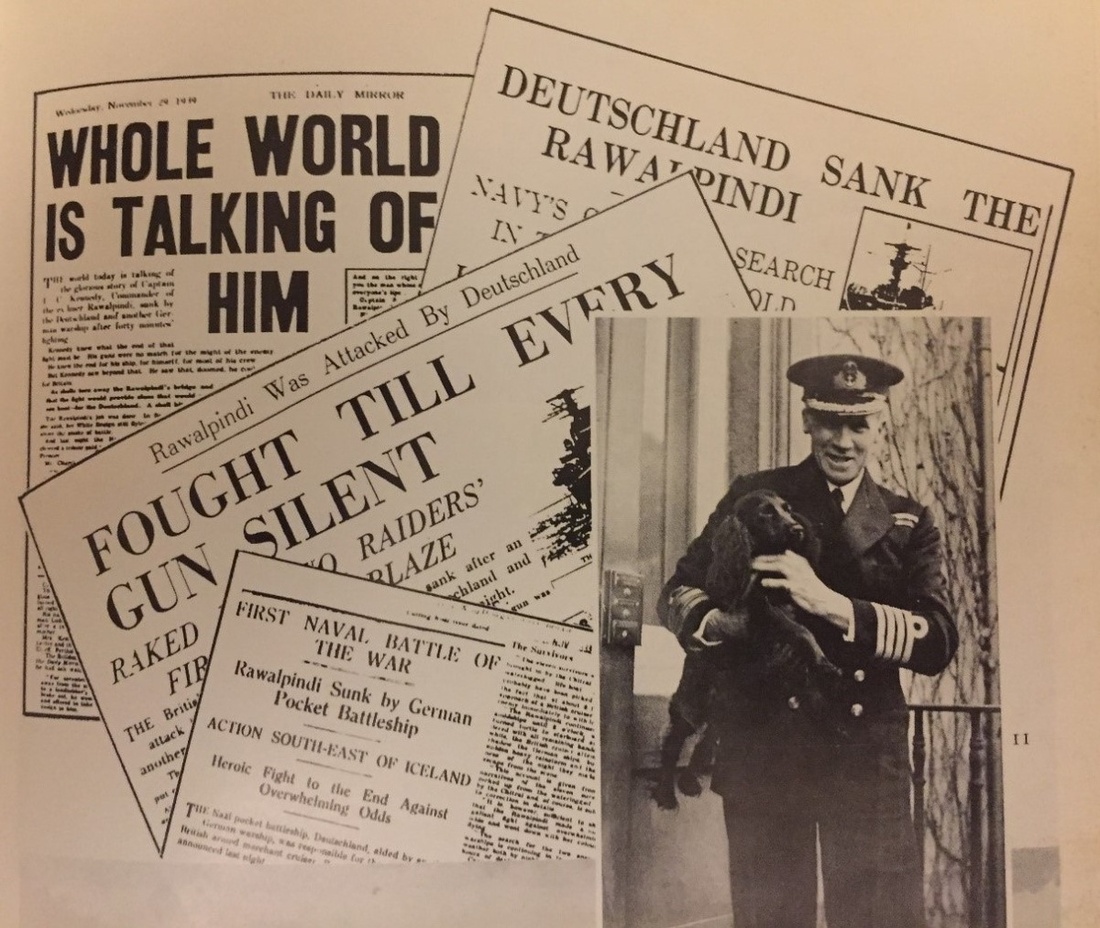

'When I stepped off the train at Waverley Station in Edinburgh in the morning, I found that every newspaper in the country had given it [Rawalpindi's action] front-page banner headlines. Nothing excites the British in wartime more than news of defeat against the odds, and this was a classic of its kind: the first surface action of the war in which an old, semi-armed former passenger liner had defied two powerful battleships; in which the bulk of her crew were pensioners and reservists and the captain [Edward Kennedy]at the age of sixty had been recalled to sea after seventeen years on the beach; but it set the stamp on how the Navy was going to fight the war.

In the House of Commons the Prime Minister, Neville Chamberlain, summed it up: 'They must have known as soon as they sighted the enemy that there was no chance for them, but they had no thought of surrender. They fought their guns till they could be fought no more. They then - many of them - went to their deaths and thereby carried on the great traditions of the Royal Navy. Their example will be an inspiration to those who come after them.'

Ludovic Kennedy describes the immediate response to his gallant father's action in the Rawalpindi in November 1939; On My Way to the Club, refers.

An outstanding Great War and Second World War group of six awarded to Able Seaman F. Skelley, Royal Fleet Reserve, late Royal Navy

Recalled on the renewal of hostilities, he joined the armed merchant cruiser Rawalpindi, thereby sharing in her gallant - impossible - contest with the mighty Scharnhorst and Gneisenau off Iceland on 23 November 1939

Offered an opportunity to surrender by the enemy, Captain Edward Kennedy, R.N., refused point-blank, telling his Chief Petty Officer:

"We'll fight them both, they'll sink us, and that will be that. Good-bye."

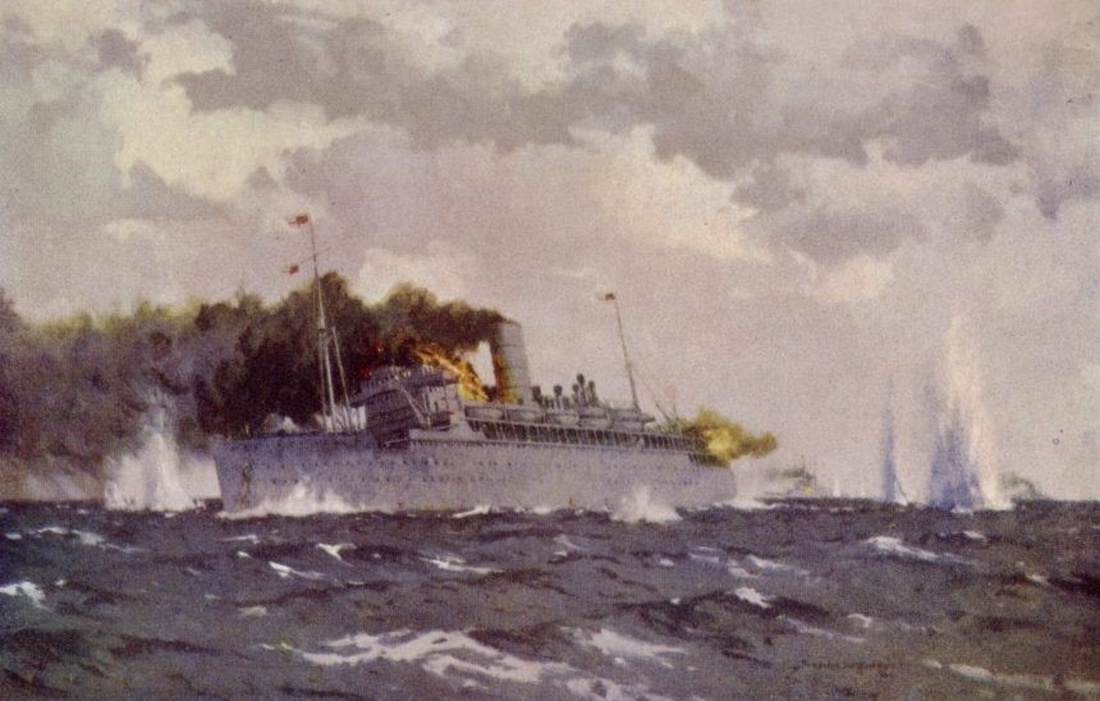

Rawalpindi duly fought an action of just 14 minutes duration, her superstructure being laid waste and set ablaze by the enemy's combined armament of eighteen 11-inch guns

Among the handful of survivors picked up by Rawalpindi's Northern Patrol consort Chitral was Able Seaman Frederick Skelley. He - and nine of his shipmates - were duly afforded much adulation on their return home:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Tzmld9GJYYQ

British War and Victory Medals (J. 59481 F. Shelley, Boy 1, R.N.); 1939-45 Star; Atlantic Star; War Medal 1939-45; Royal Fleet Reserve L.S. & G.C., G.VI.R., 1st issue (J. 59481 (Ch. B 219995) F. Skelley, A.B., R.F.R.), light attempted erasure of rate on the first, generally very fine (6)

Frederick Skelley was born in Shepherd's Bush, London on 17 June 1901, and joined the Royal Navy as a Boy 2nd Class in September 1916.

Having then attended the training ship Powerful, he served in the battleship H.M.S. Iron Duke from July 1917 until March 1921, in which period he saw extensive action in the Allied intervention in the Russian Civil War.

Coming ashore as an Able Seaman 'time expired' in June 1931, Skelley enrolled in the Royal Fleet Reserve, and it was in this capacity that he was recalled on the renewal of hostilities, when he joined the armed merchant cruiser Rawalpindi. He remained likewise employed up until her loss on 23 November 1939 and was fortunate indeed to be among just 37 survivors from her ship's company.

Loss of the "Rawalpindi"

In the annals of the Royal Navy may be found numerous examples of heart-rending self-sacrifice and valour that command deep admiration and respect: quite exceptional - and inspiring - examples of self-sacrifice enacted in the face of hopeless odds.

High on the list of such actions must be the armed merchant cruiser Jervis Bay's clash with the pocket battleship Admiral Scheer, mid-Atlantic, in November 1940. In turning to face the enemy's six 11-inch guns, versus his own ancient armament of 6-inch guns, Captain Edward Fegen, R.N., well knew he was embarking on a journey of no return: he was last seen standing on Jervis Bay's mangled fore bridge with a shattered arm.

On that occasion, at least, there were sufficient survivors to bear testament to a gallant captain's deeds: his award of his posthumous V.C. was announced in The London Gazette on 22 November 1940.

A year earlier - virtually to the day - another armed merchant cruiser captain faced far greater odds: his name was Edward Kennedy, a 60-year-old veteran of the Boxer Rebellion and father of the well-known author and broadcaster, Ludovic Kennedy. In his command Rawalpindi - like Jervis Bay armed with Great War vintage 6-inch guns - he had the great misfortune to run into the mighty Scharnhorst and Gneisenau off Iceland. In common with Edward Fegen, he faced his impending fate in true Nelsonian-style, ignoring two enemy signals to surrender. Instead, he bade farewell to one of his Chief Petty Officers in typically forthright terms:

"We'll fight them both, they'll sink us, and that will be that. Good-bye."

Rawalpindi duly fought an action of just 14 minutes duration, her superstructure being laid waste and set ablaze by the enemy's combined armament of eighteen 11-inch guns. The gallant Kennedy was not among the handful of survivors picked up by the enemy, or her Northern Patrol consort Chitral, which later ventured to the scene of battle: at length eye-witness statements of his actions in his ill-fated command bore testament to rare valour.

By popular account, the Admiralty's Honours & Awards Committee appear to have over-looked the true scale of Kennedy's deeds that day for - after much prevarication - he was awarded a posthumous mention in despatches. Their Lordships did however ordain to send his widow an official 'Letter of Appreciation', inscribed on vellum, expressing their gratitude for her husband's 'undaunted gallantry in gladly accepting battle and fighting his ship against overwhelming odds; and going down with her Colours flying': they added that it was a 'fitting end, such as he might himself have chosen, for the life of a fine and fearless seaman.'

Such strong words may well have concluded the citation for the award of a posthumous V.C., so it remains a matter of contention as to why Kennedy - unlike Fegen - was not considered for the nation's premier award. The answer appears to lie in a failure to exploit eye-witness evidence for, as revealed in one Admiralty memorandum dated 9 January 1940, the statements made by the 11 survivors picked up by the Chitral had by that date attracted but a 'cursory glance': when later Rawalpindi's remaining survivors - in captivity - submitted statements supporting the award of the V.C., it was too late and to no avail.

The Admiralty's decision to grant a posthumous mention in despatches to Kennedy caused some consternation when news of Fegen's bravery became apparent in November 1940. In making his submission for an award in the latter's case, the private secretary to the Secretary of the Admiralty noted that 'the only possible relevant case in this war is that of the late Captain Kennedy of Rawalpindi, who was not awarded the Victoria Cross': he then argued that because Jervis Bay's action lasting nearly an hour - and the fact that her convoy largely escaped - Fegen's case might be deemed different. The Secretary of the Admiralty supported those observations by stating that the Rawalpindi 'had not the speed to escape and her end came soon': in so doing - we must hope - he must have been unaware that Kennedy had declined two enemy signals inviting him to surrender.

In early 1946, the Naval Intelligence Department obtained copies of the relevant battle reports submitted by the captains of Gneisenau and Scharnhorst: they clearly stated that two signals requesting Rawalpindi's surrender were sent and received - and declined with the meaningless signal 'FAM'.

In his submission to the Admiralty's Honours & Awards Committee in respect of the posthumous award of the V.C. to Captain Edward Fegen, the 2nd Sea Lord, Admiral Sir Charles Little stated:

'Comparisons are always odious and at first sight it is not easy to draw a clear distinction between the action of Captain Fegen and that of Captain Kennedy. Neither in reality had any choice but to pursue the path of duty which he did. If Captain Fegen had not placed himself between the enemy and his convoy, thus allowing the latter a better chance of escape, he would have been branded as a coward and hounded out of the Service. He must often have pictured, during the 14 months he was commanding the Jervis Bay, the situation in which he finally found himself and acted in the only way possible. Similarly with Captain Kennedy … To the uneducated public who are interested in naval questions it would not be easy to contrast the two actions. This is unfortunate but I do not think it should stop us from pursuing the correct course in regard to the Jervis Bay and I concur in the proposal of the award of the V.C. to Captain Fegen.

It was only ten days ago I heard from Captain Kennedy's son [Ludovic Kennedy] and I enclose the correspondence.'

Yet in Captain Kennedy's case, compelling enemy evidence established the fact he did have another choice than 'to pursue the path of duty': with no convoy to defend, he had the possible - albeit difficult - option of scuttling his command, at the enemy's behest.

That he didn't was the mark of the man, who, by the Admiralty's own admission was 'a fine and fearless seaman' and, as recounted by Ludovic Kennedy, a man who felt bound to 'make himself good': patently - beyond reasonable doubt - had the occasion arisen, Captain Edward Kennedy would have acted no differently in defending a convoy.

Comparisons are indeed 'odious' but not perhaps always so. Had Their Lordships been aware that Kennedy had been given the option to surrender - scuttle his ship - then retrospective comparison to Fegen's case was surely justified: with no convoy to defend, Kennedy did have that option.

By way of consolation his widow was granted a Grace and Favour Apartment in Hampton Court Palace in 1943, a rare honour indeed. Moreover, as related by Ludovic Kennedy in his autobiography, 'the belief that my father did in fact win a V.C. persisted for many years, indeed still does today. Quite recently (1987) I received a letter which credited him with the award. The writer was on the staff of the National Maritime Museum.'

In terms of the history of V.C., the ultimate decision of Their Lordships in Kennedy's case provides refreshing evidence to counter the contention that such awards are largely politically motivated: if ever there were a case for political influence being brought to bear - amidst the flurry of media coverage that beckoned the award of the first V.C. of the 1939-45 War - this was it.

But Their Lordships were not for turning.

Subsequent career

In April 1940, following his harrowing experiences in Rawalpindi, Skelley joined the Royal Eagle, an Admiralty requisitioned Thames paddle steamer. Alas, no pleasure was to be found in her during her forthcoming role off Dunkirk:

'Built by Cammell Laird at Birkenhead for General Steam Navigation Company, and commissioned in the summer of 1932, the Royal Eagle was advertised as the 'largest and most luxurious pleasure steamer ever seen on the Thames'. One of the new features incorporated into the design of the vessel was a large glass-enclosed lounge on the main deck, where passengers could enjoy the experience of sea travel without being subjected to the wind and spray.

Every day of the week, except Friday, between Whit-Saturday and mid-September the Royal Eagle left Tower Pier at 09:30 bound for Southend, Margate and Ramsgate, returning to London by 20:45. The day return fare in 1934 was 11s (55p) and a hot luncheon could be purchased on board for 3s 6d (17½p).

By 1940 the happy faces of day-trippers had been replaced by the weary faces of soldiers as the Royal Eagle played an important part in the evacuation of Dunkirk. She spent the rest of the war in the Thames Estuary as part of the anti-aircraft defence chain.'

'The Royal Museums Greenwich' website, refers.

Frederick Skelley was surely among those 'weary faces', for Royal Eagle made at least three trips to Dunkirk - bringing home around 3,000 troops - and was dive-bombed on no less than 43 occasions. He was released 'Class A' in November 1945.

Subject to 20% VAT on Buyer’s Premium. For more information please view Terms and Conditions for Buyers.

Sold for

£2,000

Starting price

£350