Auction: 22003 - Orders, Decorations and Medals

Lot: 355

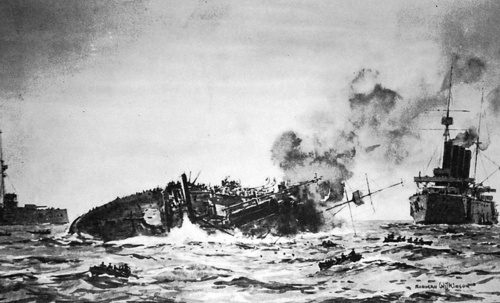

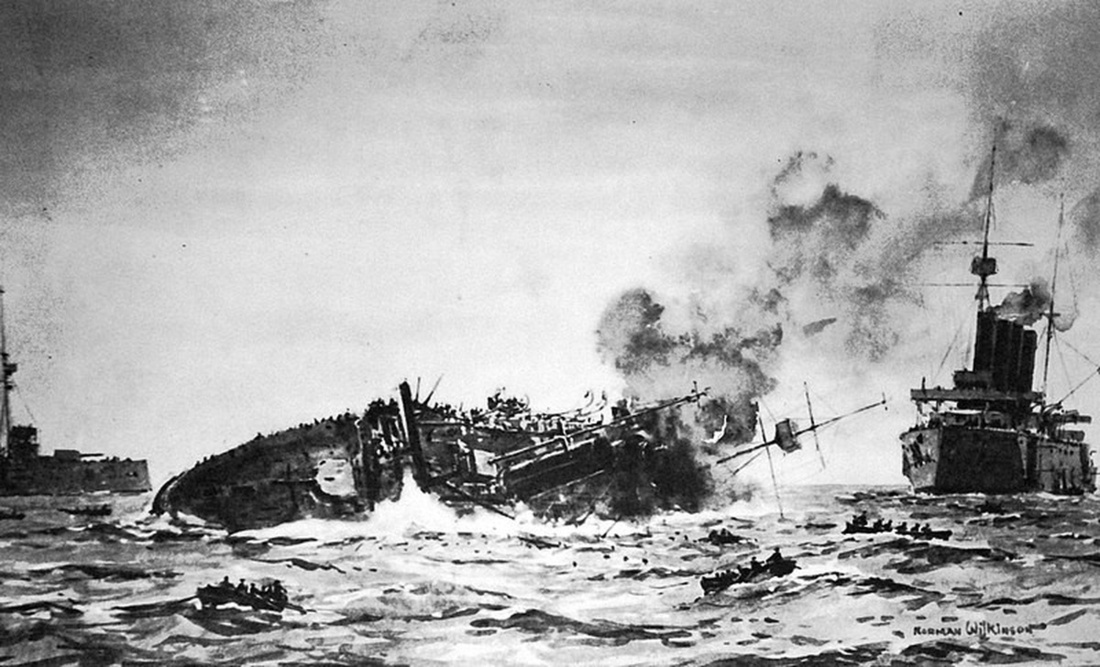

22 SEPTEMBER 1914: DISASTER OFF THE 'BROAD FOURTEENS'

'The British Admiralty explained the Broad Fourteens disaster in 1914 to the general public in just 450 words. Winston Churchill was more generous. In 'The World Crisis' he expended 1,800 - about a word for each casualty.'

Three Before Breakfast, by Alan Coles, refers

The Great War campaign group awarded to Engineer Rear-Admiral P. J. B. Huxham, Royal Navy, who survived the sinking of H.M.S. Aboukir in the North Sea by the German submarine U-9 on 22 September 1914 - along with her consorts Cressy and Hogue on the same date

Owing to their being obsolete - poorly armed and armoured - the ships of the 7th Cruiser Squadron were nicknamed "The Live Bait Squadron": it was a prescient accolade, for 62 officers and 1,397 men were killed on that fateful day in September 1914, one of the greatest disasters to befall the Royal Navy in the Great War

Huxham displayed notable gallantry in returning to the stricken Aboukir's engine room and was duly commended for his actions at the subsequent Admiralty Board of Inquiry

He also survived the loss of the Cressy, aboard which he had been plucked some 30 minutes after Aboukir's demise: tossed into the air by the impact of his second torpedo strike of the day, he was compelled to abandon ship stark naked

1914-15 Star (Eng. Lt. Cdr. P. J. B. Huxham, R.N.); British War and Victory Medals (Eng. Lt. Cdr. P. J. B. Huxham, R.N.), good very fine (3)

Percy John Burdick Huxham was born at Stoke Damerel, Devon on 29 December 1880 and entered the Royal Navy as a Probationary Assistant Engineer in June 1902.

By the outbreak of hostilities in August 1914, he was serving as an Engineer Lieutenant-Commander in the cruiser H.M.S. Aboukir, a ship of the 7th Cruiser Squadron - a.k.a. "The Live Bait Squadron".

Disaster in the North Sea

All three cruisers were torpedoed and sunk in the North Sea by the German submarine U-9 on 22 September 1914. The Aboukir was the first to be hit at 06:20; her captain thought that she had struck a mine and ordered the other two ships to close in order to transfer his wounded men. The Aboukir quickly began listing and capsized, sinking at 06:50.

A glimpse of Huxman aboard the Aboukir immediately after she has been torpedoed is found in Three Before Breakfast, by Alan Coles:

'Like his captain, Percy Huxham, the Engineer Lieutenant-Commander, also had the idea of flooding the wings. He raced to the engineer's office amidships only to find no-one there. He rang the engine-room: no reply.

Although by now everyone had come up from below, Huxham descended into the port engine room where the oil lamps still burned and the engines turned slowly ahead. He moved over to the starboard side where the engines were stopped. But in neither compartment was there a sign of water. Huxham was surprised by the absence of life, but he found it when he returned to the upper deck where more than 600 men were gathered.

He was anxious to locate Everitt, his immediate superior, but was unable to spot him. On the quarter-deck he was approached by Chief Engine Room Artificer Bill Smith, who knew more about the lay out of the Aboukir than most of the officers as he had been in charge of the ship's working party when they were in dockyard.

"What about flinging the wings, sir," Smith suggested. "The ship is going to port. Can I flood the starboard wings to right her?"

"That's what I thought of doing," answered Huxham.

He looked across the deck, over which water was lapping, and watched an argument between Lieutenant-Commander Jim Parker and George Dobinson, the Carpenter.

"The captain wants the starboard wing compartments flooded," shouted Parker.

The old Carpenter refused to leave the quarter-deck. "That's engineers' work," he protested.

Huxham ended the conversation by assuring them, "we're trying to do all we can, Jim, but first we've got to get the compartment keys from the sentry."

Smith followed Huxham to the companionway and down to the ward-room flat. Usually a marine sentry was on duty alongside the keyboard and rifle rack. He had gone - and so had the keys. With him had vanished Drummond's last chance of righting the ship. Minute by minute the angle of the list increased. Soon Drummond would have to give the order to abandon ship … '

Huxham survived Aboukir's sinking, swimming to a cutter sent over from the Cressy. But he was in for a shock. For having been sent below to get dry clothing from his opposite number's cabin, Cressy too was torpedoed:

'From a drawer Huxham selected a vest and a pair of pants but before he could change into them he was tossed in the air by the impact. Snatching a blanket from the bunk, he wrapped it round himself and went into a passage. Water was already pouring into the gun-room flat, so he scrambled to the quarter-deck and sat on the port side.

"This is roughly the same position I was in when the Aboukir sank," he mused ruefully.' (ibid)

About 30 minutes later, the Cressy toppled over, keel uppermost, 'like some incongruous tombstone'. Stark naked, Huxham took to the drink for a second time, and clambered aboard a whaler which was up to its gunwales in water. Thankfully, the trawler Coriander hove into view before the whaler capsized, and the survivors were embarked for Lowestoft, Coriander's home port, latterly with a destroyer escort.

At the ensuing Admiralty Board of Inquiry, Huxham was able to reveal that his efforts to save the Aboukir had been further hampered by faulty doors on the armoured deck between the wing and lower bunkers. Three of them were permanently jammed.

Subsequent career

Huxham transferred to the Naval Ordnance Department after Aboukir's loss and appears to have been given charge of gun mountings at Vickers.

He was advanced to Engineer Commander in July 1919 and to Engineer Captain in December 1928, prior to being placed on the Retired List as an Engineer Rear-Admiral in December 1934.

Recalled on the renewal of hostilities in September 1939, he served on the staff of the Flag Officer, Clyde until finally released as 'Class A' in September 1946. He died at Okehampton, Devon in November 1953.

Postscript

On 22 September 2014 - the centenary of the loss of the Aboukir, Cressy and Hogue - a special Drum-Head ceremony was conducted by the Bishop of Rochester. Three lifebelts recovered from the ships formed part of the backdrop.

In the same year, Dutch Maritime Productions released a related commemorative film:

https://www.dutchmaritimeproductions.com/portfolio-item/live-bait-squadron/

Subject to 20% VAT on Buyer’s Premium. For more information please view Terms and Conditions for Buyers.

Sold for

£700

Starting price

£220