Auction: 22001 - Orders, Decorations and Medals

Lot: 429

(x) The superb Naval General Service Medal awarded to Midshipman James Pendergrass, who cut short a promising career as an officer in the Royal Navy to instead serve with the Honourable East India Company and who, as Captain of the H.E.I.C. ship 'Hope', commanded her during the Battle of Pulo Aura - an action later brought to life in one of the famous naval novelist Patrick O'Brian's 'Aubrey-Maturin' books, 'H.M.S. Surprise' - and for which service Pendergrass was awarded a rare £50 Lloyd's Patriotic Fund sword which is still known to be extant

Naval General Service 1793-1840, 1 clasp, 23rd June 1795 (James Pendergrass, Midshipman), good very fine

James Pendergrass, born in 1767, appears from an early age to have been destined for a life at sea full of adventure and action. Though clearly set on a career in the service of the Honourable East India Company (as accounts of his later life will show) he earned his Medal and Clasp for the Battle of Groix as a Midshipman aboard the 100-gun H.M.S. Queen Charlotte, the flagship of the British fleet commanded by Admiral Lord Bridport - otherwise known as Alexander Hood, scion of that famous naval family.

The circumstances of his being on board were in themselves unusual: as a junior officer in the employment of 'John Company', he was on board the Princess Royal when she was captured by French privateers in the Straits of Sunda in September 1793. Parolled and returned home soon after, whilst waiting for a new ship (his future command, the Hope), he successfully applied to join the Royal Navy and found himself in the thick of the action on 23 June 1795. The Queen Charlotte led the British attack and took on a number of enemy vessels one after the other including the Alexandre, Regeneree, Formidable, and Sans Pareil. Unsurprisingly this resulted in the Queen Charlotte receiving the heaviest casualties of any British ship engaged in that action - 34 killed and wounded, though still a fraction of those inflicted upon the French.

Pendergrass came to the notice of the Queen Charlotte's captain - Sir Andrew Snape Douglas - for both his actions that day and for attempting to save the life of a shipmate at Spithead:

'To Mr James Pendergrass, Portsmouth, 13th of Aug. 1795.

Sir - the moment I received your letter from Plymouth, requesting your discharge, I answered it by saying that I most cheerfully gave it to you, as it appeared to afford an opportunity for advancing your interest; at the same time I regretted the loss of your services on board the Queen Charlotte. I now desire to repeat to you my warmest approbation of your conduct during the time you served under my command, particularly for the humanity you showed in your endeavours to save the poor man who fell overboard, and for your steadiness and bravery in the late action with the enemy's fleet, on the 23d of June last. My best wishes will always attend you. I am sorry you have not received my letter, directed to Plymouth, as it may have led you to imagine that I had overlooked the merit to which you are so justly entitled in testimony of from me. I am, Sir, &c., A.S. Douglas' (Hereford Times, 30 November 1844, refers).

Whilst Pendergrass may therefore have progressed well in the Royal Navy (especially with the patronage of such a well-regarded officer) he decided to return to the employment of the East India Company.

"Linois had thrown away a prize worth at least £8 million through mere timidity"

Pendergrass took command of the Hope in 1802 and remained as such for the next 15 years. Launched in 1797, with a crew of around 140 men and armed with 36 small- to medium-calibre guns, the Hope was a typical East Indiaman of the period. Pendergrass's inaugural voyage in command coincided with a most famous - and indeed unique - incident of the Napoleonic Wars, when the home-bound China Fleet happened upon a powerful French squadron commanded by Rear-Admiral Charles-Alexandre, Comte de Linois, on 14 February 1804. The captains of the British vessels, under the command of Commodore Nathanial Dance, decided to stand and fight rather than turn and flee, knowing that from a distance their ships looked much like Royal Navy warships.

The subsequent engagement has been immortalised in print by the renowned historical novelist Patrick O'Brian, who puts his famous characters Captain Jack Aubrey and Doctor Stephen Maturin in the heart of the action, helping to defend - and emerge victorious - against Linois's ships. O'Brian takes up the story from the moment H.M.S. Surprise encounters the fleet:

'The leeward division...was made up of country ships bound for Calcutta, Madras or Bombay...But those to windward, all sixteen of them the larger kind of Indiamen that made the uninterrupted voyage from Canton to London, were already in a formation that would not have done much discredit to the Navy.

'And are you indeed fully persuaded that they are not men-of-war?' asked Mr. White. 'They look wonderfully like, with their rows of guns; wonderfully like, to a landsman's eye.'

After requesting a council-of-war with the respective East India captains (which, even in this fictional setting, would have included Pendergrass) Jack Aubrey lays out his plan:

'The larger Indiamen will form in line of battle, taking all available men out of the rest of the convoy to work the guns and sending the smaller ships away to leeward. I shall send an officer aboard each ship supposed to be a man-of-war, and all the quarter-gunners I can spare. With a close, well-formed line, our numbers are such that we can double upon his van or rear and overwhelm him with numbers: with one or two of your fine ships on one side of him and Surprise on the other, I will answer for it if we can beat the seventy-four, let alone the frigates.

'Hear him, hear him,' cried Mr. Muffit, taking Jack by the hand. 'That's the spirit, God's my life!'

The tension continues to build as the two opposing sides draw ever nearer:

'The East India captains could handle their ships, of that there was no doubt. They had performed this manoeuvre three times already and never had there been a blunder nor even a hesitation. Slow, of course, compared with the Navy; but uncommon sure. They could handle their ships: could they fight them too? That was the question.

'I admire the regularity if your line, sir,' said Jack. 'The Channel fleet could not keep station better.'

'I am happy to hear you say so,' said Muffit. 'We may not have your heavy crews, but we do try to do things seaman-like. Though between you and me and the binnacle,' he added as a personal aside, 'I dare say the presence of your people may have something to do with it. There is not one of us would not sooner lose an eye-tooth than miss stays with a King's officer looking on.'

O'Brian creates a wonderful pen-portrait of the fleet which cannot be far from reality - though Pendergrass does not feature in glowing terms!

'This movement brought the Indiamen to the point where the Surprise had turned, while the Surprise, on the opposite tack, passed each in succession, the whole line describing a sharp follow-my-leader curve; and as they passed he stared at each with the most concentrated attention. The Alfred, the Coutts, each with one of his quartermasters aboard...the Wexford, a handsome ship in capital order...a fine eager captain who had fought his way out of a cloud of Borneo pirates last year. Now the Lushington...Ganges, Exeter and Abergavenny...Addington, a flash, nasty ship: Bombay Castle, somewhat to leeward - her bosun and Old Reliable were still at work on the breechings of her guns. Camden...Cumberland, a heavy, unweatherly lump, crowding sail to keep station. Hope, with another dismal old brute in command - lukewarm, punctilious. Royal George, and she was a beauty; you would have sworn she was a post ship.

As the action commences the drama unfolds, with Pendergrass being singled-out by the French:

'Linois's next move took him by surprise, however: the Admiral, judging that the head of the long British line was sufficiently advanced for his purposes, and knowing that the Indiamen could neither tack nor sail at any great speed, suddenly crowded sail. 'By God', he said, 'he means to break the line. Lee: tack in succession: make all practicable sail.'

As the signal broke out, it became even more certain that this was so. Linois was setting his heavy ship stright at the gap between the Hope and the Cumberland, two of the weakest ships. He meant to pass through the line, cut off the rear, leave a ship or two to deal with what his fire had left, luff up and range along the lee of the line, firing his full broadside.'

Returning to reality, after a brief exchange of fire Linois bore away and did not attempt a serious action: Dance and the East India convoy actually pursued them for two hours, with Pendergrass and the Hope coming close to catching the 16-gun Aventurier, though he was ultimately unable to overtake her. This undoubtedly made good an early error in the action when, eager to close with the French, the Hope carried too much sail and briefly collided with the Warley.

Homeward Bound, Reward, and Later Life

The whole fleet made it safely back to Britain where, understandably, there was much celebration. Commodore Dance was made a Knight Bachelor by King George III; a £50,000 prize fund was ordered to be distributed between the captains and crews of the ships; and Lloyd's Patriotic Fund presented ceremonial swords, silver plate, and money to individual officers involved. The Captain of each vessel was awarded a sword worth £50; Pendergrass received one such sword, which tantalisingly appears to have been recently offered for sale by the high-end U.S. antiques shop 'M.S. Rau' of New Orleans.

Further mention is made of Pendergrass's rewards: 'Capt. Pendergrass received, in addition to what Nicholas Carlisle mentions in his work, from the East India Company 500 guineas, and 50 guineas for a piece of plate; and from the owners of his ship, the Hope, 400 guineas. (Hereford Times, 30 November 1844, refers).

Pendergrass and the Hope made five further voyages to the East Indies between 1805 - 1816; one of these resulted in yet another encounter with Rear-Admiral Linois in his 74-gun Marengo, but this time the merchantmen were escorted by a powerful British man-of-war and after a brief exchange of fire Linois again bore away. Interestingly it was on the return trip from this voyage that Pendergrass brought back seedlings of the Camellia japonica 'Incarnata', known to this day as 'Lady's Hume's Blush': her husband, Sir Abraham Hume, was Hope's managing owner and must therefore have known Pendergrass extremely well.

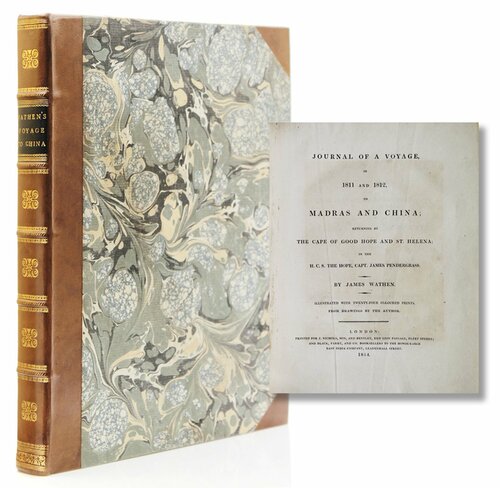

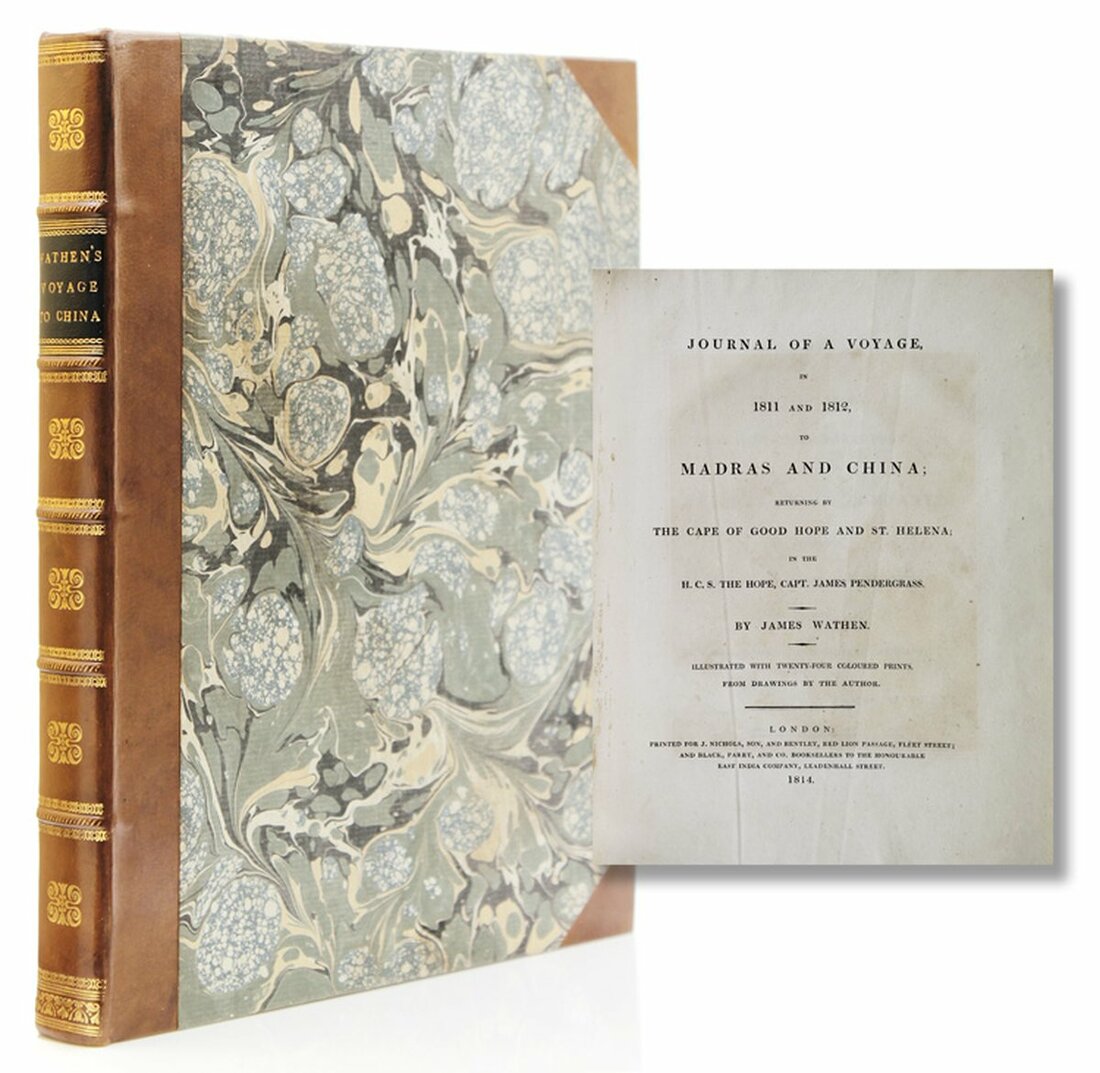

On a later journey it appears he took an old school-friend with him, a sailing which was later published into the book: 'Journal of a Voyage in 1811 and 1812 to Madras and China; Returning by The Cape of Good Hope and St. Helena; in the H.C.S. The Hope, Capt. James Pendergrass. By James Wathen. Illustrated with Twenty-Four Coloured Prints, From Drawings by the Author' (London 1814). Wathen, a native of Hereford, was known as 'Jemmy Sketch' and became well-known in his lifetime for making topographical drawings and other sketches for publications including the 'Gentleman's Magazine.

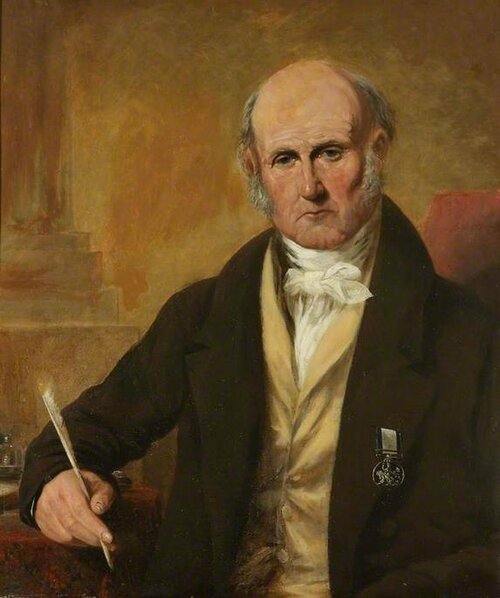

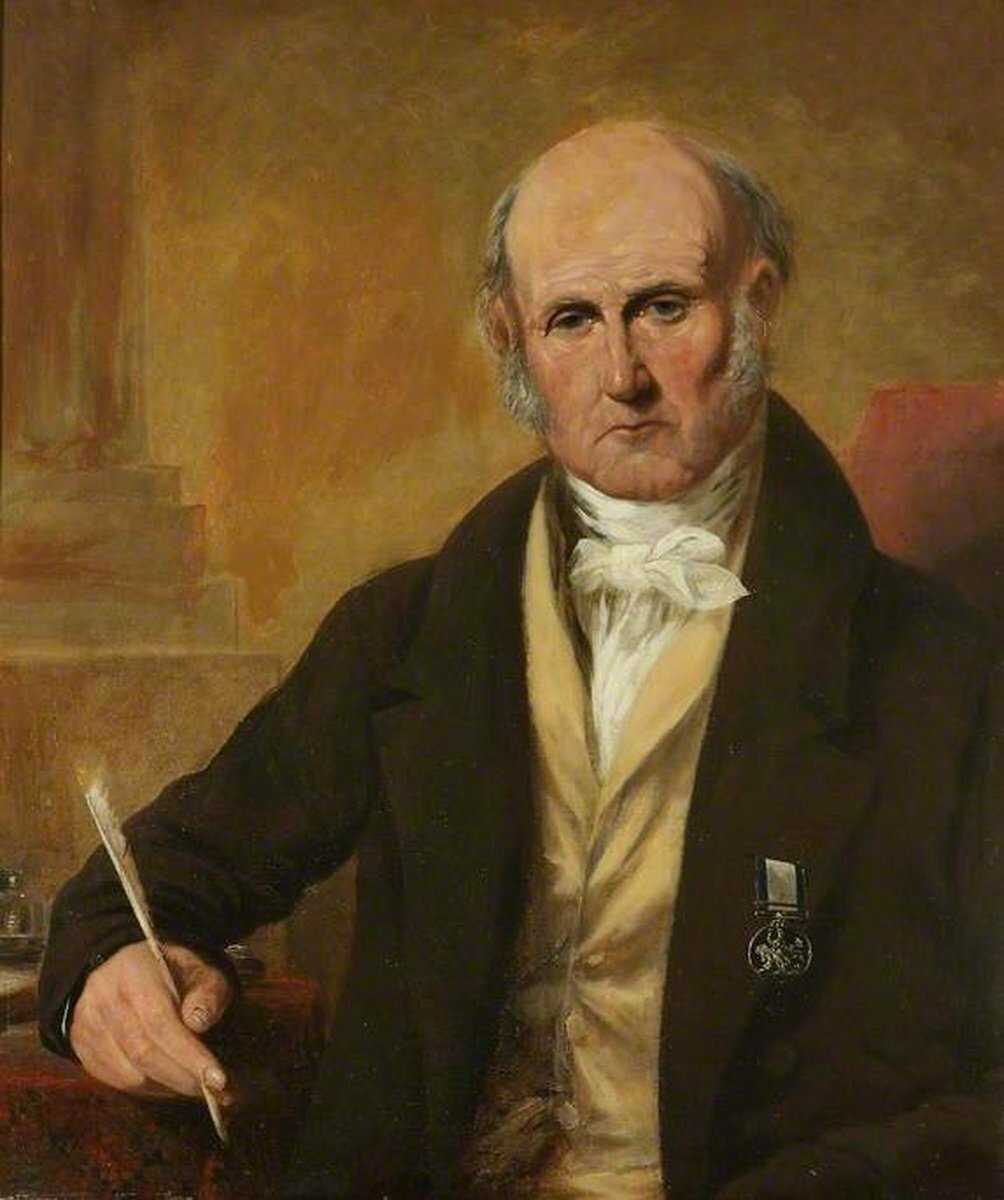

After retiring from a life at sea, likely in 1816, Pendergrass appears to have settled in Hereford; the cathedral city's hospital holds a portrait of him in old age, looking very much the patrician and proudly wearing his single-clasp Naval General Service Medal. He died in 1851, aged 85.

Subject to 5% tax on Hammer Price in addition to 20% VAT on Buyer’s Premium.

Sold for

£7,500

Starting price

£3500