Auction: 22001 - Orders, Decorations and Medals

Lot: 326

'I must here draw attention to the manner in which the heavy 24-pounder guns were impelled and managed by Captain Peel and his gallant sailors. Through the extraordinary energy and good will with which the latter have worked, their guns have been constantly in advance throughout our late operations from the Relief of Lucknow until now, as if they were light field pieces, and the service rendered by them in clearing our front has been incalculable.'

- Sir Colin Campbell

When Britain's starts to produce toy soldiers of a particular action or battle, you know that the battle in question has become a legend. Such is the case with Peel and his Naval Brigade, who can be 'purchased' from the shop on Birdcage Walk.

William Peel, son of the Prime Minister Sir Robert Peel, had already earned the Victoria Cross for his bravery before Sebastopol in October 1854, when he picked up a fizzing shell from amongst powder cases and threw it over the parapet. The following month he rode into the Sandbag Battery at Inkerman to help the Grenadier Guards save their Colours, and on 18 June 1855 he led a storming party against the Redan. The Naval Brigade he formed from the crew of H.M.S. Shannon in 1857 was superlative in its stamina, dexterity, and grit. Without Peel's heavy guns, and the heroes who manned them, it is doubtful if the Sikanderabagh could have been breached, the bridge at Cawnpore defended, or the enemy driven from Khudaganj. Yet Peel's was one of three Naval Brigades involved in the Indian Mutiny, and the other two have often been neglected.

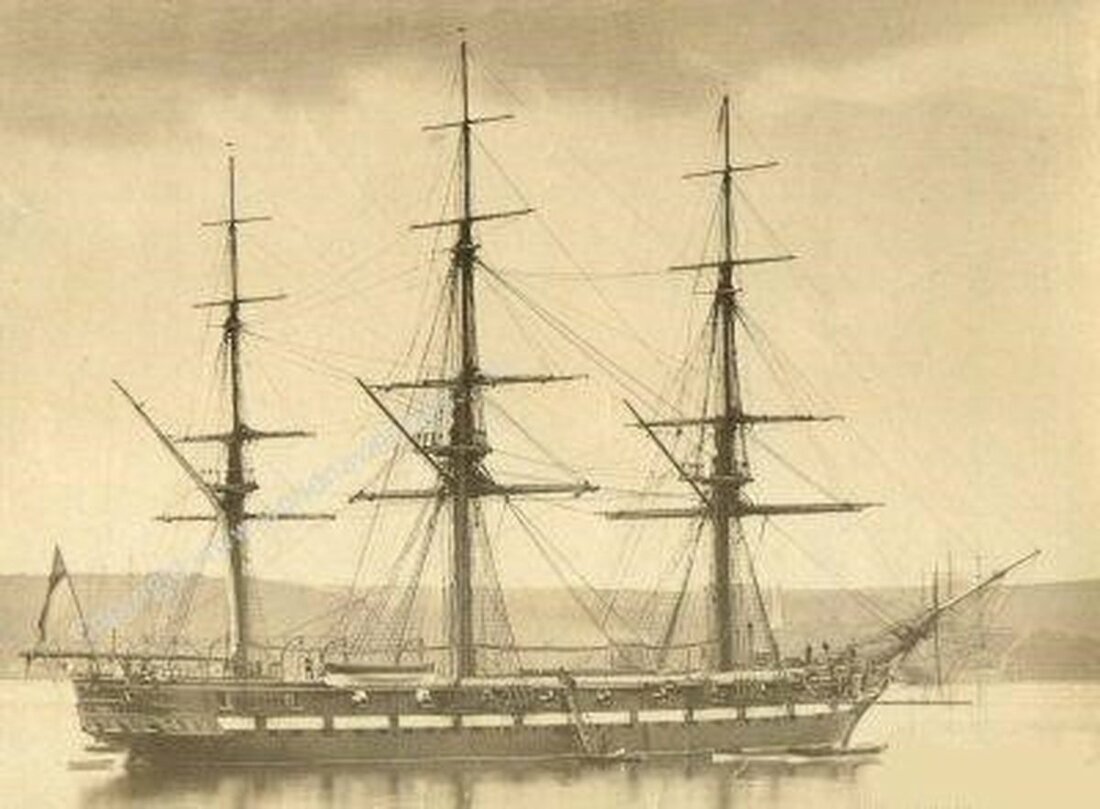

H.M.S. Pearl, under Captain E. S. Sotheby, arrived at Calcutta earlier than the Shannon and was soon ordered up the Ganges. She formed her own Naval Brigade which achieved remarkable feats of arms in the Trans-Gogra Campaign, preventing rebel forces in the northernmost regions from reaching Lucknow. The Honourable East India Company formed its own 'Indian Naval Brigade', which performed a variety of duties across the subcontinent, and whose contribution has hardly been recognised.

To have an Indian Mutiny Medal from each of these three Naval Brigades in a single Auction is, to say the least, a rare event. The medal roll lists just 533 awards for the Shannon, and 254 for the Pearl. We hope these medals continue to stand testament to the courage of the Royal Navy.

Recommended reading:

Verney, Lieutenant E. H., The Shannon's Brigade in India (London, 1862).

Verney, Major-General G. L., The Devil's Wind: The Story of the Naval Brigade at Lucknow (London, 1956).

Watson, E. S., A Naval Cadet with HMS Shannon's Brigade in India (Kettering, 1858).

Williams, Rev. E. A., The Cruise of the Pearl (London, 1859).

The superb 'Naval Brigade' Indian Mutiny Medal to Leading Stoker J. Harvey, R.N., one of Peel's 'Shannons', who did his duty against overwhelming odds at Lucknow and Cawnpore

Indian Mutiny 1857-59, 2 clasps, Lucknow, Relief of Lucknow (Jas. Harvey, Leadg. Stoker. Shannon.), very fine

James Harvey was born in Portsmouth on 11 May 1824. On 1 July 1853 he volunteered for the Royal Navy, serving initially as a Stoker aboard the paddle frigate Odin. On 1 August 1856, he transferred to H.M.S. Shannon.

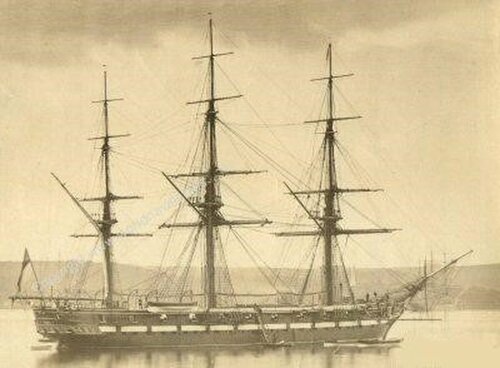

The Shannon was an imposing Liffey-class steam frigate armed with 51 guns. Originally intended for service in China, she left Hong Kong in company with the Pearl (see next Lot) when news broke of the Indian Mutiny. When she docked at Calcutta in August 1857 she was, at that time, the largest vessel to have navigated so far up the River Hooghly. Her Captain, William Peel, V.C., C.B., took a considerable risk in moving her into such shallow water, but subsequent events were to prove him a man undaunted by any danger.

Sir Patrick Grant, who was then acting Commander-in-Chief at Calcutta, knew that British forces in Oudh were woefully short of heavy guns. He ordered Peel to form a Naval Brigade comprising 'Bluejackets' from both the Shannon and the Pearl. The contingent from Pearl numbered 175 men, bringing the Naval Brigade's total strength to 408 officers and men, including Marines from both ships.

This force was armed with: ten 8-inch 68-pounders with 400 rounds of shot and shell per gun, four 24-pounders, four 12-pounders, a 24-pounder howitzer, and eight rocket tubes. 800 bullocks were required. For the voyage up the Ganges, the men and guns were to be transported in a steamer called the Chunar, as well as a flat-bottomed transport. The force left Calcutta on 29 September, heading straight towards 'The Devil's Wind'.

On 10 October, the contingent from Pearl stopped at Buxar on the Ganges, and thenceforward operated separately under the command of Captain E. S. Sotheby. The remainder of Peel's Naval Brigade, already nicknamed 'The Shannons', continued up the Ganges to Cawnpore, where British forces were gathering for the Second Relief of Lucknow. Peel kept the men occupied with constant drilling and manoeuvres. He knew that in battle, the guns would have to be moved using drag ropes, eighteen men to each gun.

Sir Colin Campbell was greeted with a great cheer when he arrived at Cawnpore on 31 October, assuming command of the army. His force only amounted to 3,400 men, made up of detachments from HM 8th, 23rd, 53rd, 82nd, 90th and 93rd Foot (including Private J. Kinnear, please see Lot 169), the 2nd and 4th Punjab Infantry, and the 9th Lancers. Peel's Naval Brigade thus proved invaluable when the force arrived before Lucknow on 15 November.

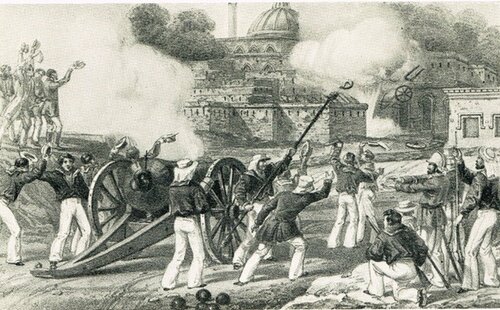

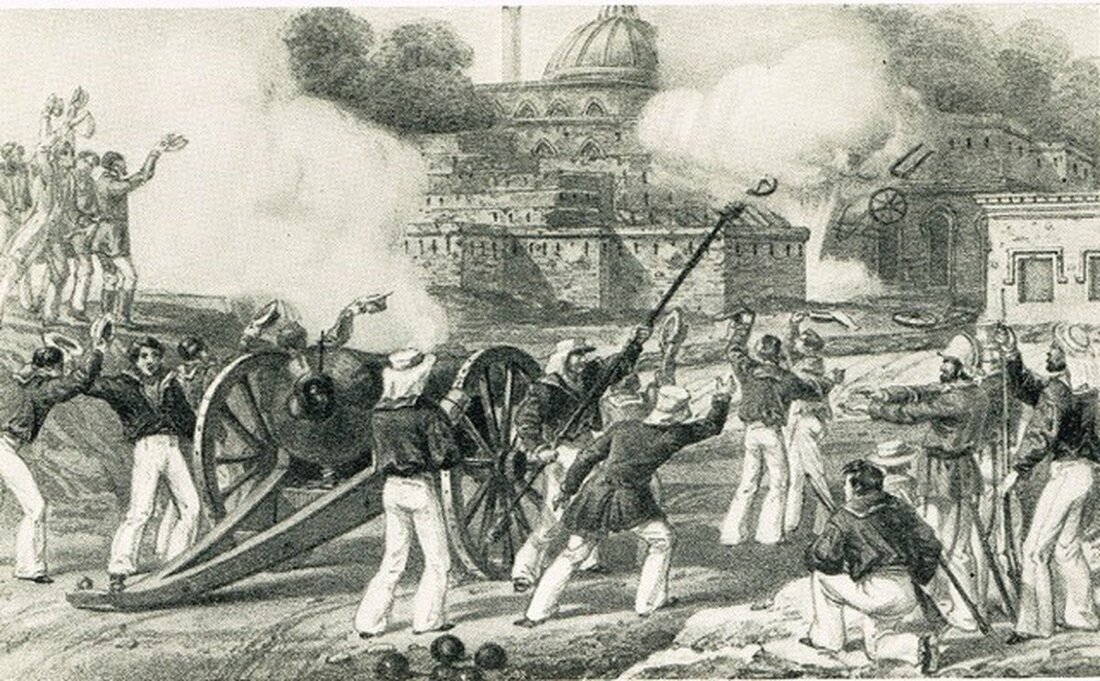

The next day, Peel's guns and two heavy guns of the Royal Artillery began a fierce bombardment of the Sikanderabagh, a huge rebel-held building, 130 yards square, with a thick, brick, loopholed wall 20 feet high, flanked by bastions at the corners. After firing for 90 minutes, the guns had created a small hole, three feet high and three and a half feet wide. As their pipers struck up the Highland Charge 'Haughs of Cromdale', men of the 93rd Highlanders surged forward in the hope of being the first to enter this 'breach', and won six Victoria Crosses.

Although losses at the Sikanderabagh were severe, the stormers were able to trap about 2,000 mutineers in a corner of the building. Remembering earlier atrocities, particularly the massacre of women and children at Bibighar, Cawnpore on 15 July (the gore at Bibighar lay undisturbed, creating a nightmarish scene for troops passing through), the stormers killed every man they found. Lord Roberts later recalled:

'There they lay, in a heap as high as my head, a heaving, surging mass of dead and dying inextricably tangled.'

The capture of the Sikanderabagh enabled Campbell's army to reach the beleaguered Residency compound, but having lost 45 officers and 496 men, Campbell realised he could not possibly hold Lucknow against the vast rebel armies in the region.

On 19 November, the evacuation of the Residency began. Women and children who for six months had suffered unimaginable terrors emerged from its shattered ramparts and filed towards Dilkushah, under the protection of the 9th Lancers. Campbell organised the evacuation so that the enemy never suspected a British withdrawal. The Naval Brigade was pivotal to this conceit: while Peel's guns and rockets pounded the Kaiserbagh as if in preparation for an assault, women and children were silently extricated from the Residency compound, under the noses of a distracted foe. Part of the rearguard, Peel's Bluejackets were among the last to quit Lucknow on the night of 22 November; it was many hours before the mutineers realised that the Residency was empty.

Return to Cawnpore

Just before leaving Cawnpore for Lucknow, Sir Colin Campbell had left 500 men to defend the city under the command of General Windham. Included in this garrison were fifty Bluejackets of the Shannon, with two 24-pounders, led by Lieutenant Hay and Naval Cadets Watson and Lascelles. Cawnpore lay on the Grand Trunk Road, its bridge of boats over the Ganges a vital artery for British supply and communication. Most of Campbell's reinforcements arrived via Cawnpore (hence why the massacre there had such impact).

On 19 November, Windham's tiny garrison was invested by 25,000 mutinous sepoys of the Gwalior Contingent, led by Tantia Tope. Windham's men, including the Bluejackets, dug entrenchments at each end of the bridge of boats and managed to hold it for ten days. Since Stoker Harvey was awarded the 'Relief of Lucknow' clasp, he was almost certainly at Lucknow at this time, and not part of this 50-strong detachment at Cawnpore.

Hearing of Windham's plight, Campbell left Sir James Outram with a small force to hold the Alum Bagh, near Lucknow. With the remainder of his army, including the Naval Brigade, Campbell dashed southwards. When heavy gun-fire could be heard from Cawnpore on 27 September, Campbell pressed ahead with his cavalry and horse artillery. He linked up with Windham's entrenchments the following day, and to his great relief, the bridge of boats remained intact.

The Naval Brigade arrived on the northern bank of the Ganges two days later. The mutineers had massed their artillery on the southern bank, aiming to destroy the bridge of boats, but Peel's guns quickly silenced them. Over subsequent days, Campbell arranged for the sick, wounded and non-combatants from Lucknow (over 2,000 souls) to be escorted to Allahabad, thence to Calcutta. This left him free to conduct offensive operations. He received reinforcements, including a wing of the 42nd Foot, bringing his total force to 600 cavalry, 5,000 infantry and 35 guns. On 6 December, he launched a full-scale assault across the river. In The Devil's Wind: The Story of the Naval Brigade at Lucknow (1956), G. L. Verney tells how the Naval Brigade lifted morale when the assault began to falter:

'Every attempt at forward movement was met by a storm of shot, shell and bullets, the slow rate of fire of the [rebel] muskets being compensated by the large number of men handling them. Each rush cost a few lives and it looked bad. In the clouds of dust and smoke which billowed across the plain, it was hard for commanders to see what was happening or why the advance in that area was making so little progress. To those in front, it seemed that increased artillery support was their only hope.

Suddenly, however, the men of the 53rd Foot and the 4th Punjab Infantry, lying down near the bridge and extended short of the bank of the Canal, heard a rumble of wheels behind them, and there they saw Captain Peel, followed by a 24-pounder gun, hand-drawn and double-crewed, some forty Seamen, running hard, followed by a limber. "Action Front" shouted Peel, and the long lines of sailors swung round on the very bridge itself. Firing, sponging, loading, firing, they overwhelmed the enemy musketeers and gunners. Behind them tore Captain Gray and his Marines and, inspired by this dramatic intervention, the Infantry rose with a cheer, charged over the bridge or through the Canal and drove with their bayonets right into the rebels' position; their guns were taken and their men fled.'

'Our guns took the lead'

Once this crossing had been achieved, the mutineers fled by the Calpee road, abandoning Cawnpore to the British. The Naval Brigade did not stop there, however. Moving their heavy guns with the lightness of a pistol, they joined in the pursuit of the Gwalior Contingent, even forming the vanguard of Campbell's force. E. S. Watson, a Naval Cadet no older than 15, described in a letter to 'My Dear Mama' how the Naval Brigade earned the admiration of the whole army:

'Our guns took the lead of all, consisting of three 24-pounders, one 8-inch howitzer, and two rocket tubes. We advanced along the road a little way which led us right out into the open. Across the plain, the enemy were in force among some jungle, and had several guns. The rest of the force were drawn up two deep in a long line, a few hundred yards in our rear. After firing at each other for some time, we began advancing the guns one by one, keeping with the front line of skirmishers all the while. As we began advancing, there was a kind of rush forward among the enemy; and Captain Peel said afterwards that he had made up his mind they would charge the guns, but they fell back again, and there seemed to be a great deal of confusion among them, as if they were quite surprised at heavy guns coming along taking the lead like ours did.'

The Naval Brigade next saw action on 2 January 1858, at the village of Khudaganj near Futteghur. This area needed to be captured so that Campbell's force could be reinforced from the Punjab. Peel's guns again took a dreadful toll on the enemy, holding a large body of enemy cavalry at bay. This enabled Brigadier's Greathed's Division to cross a treacherous nullah and seize the village.

On 12 February, the Naval Brigade left Futteghur and took part in the final capture of Lucknow in March 1858. By then, some 100,000 mutineers had concentrated in the city, against whom Sir Colin Campbell could muster only 18,277 of all ranks. The assault began in earnest on 9 March, and it was while siting his guns before La Martinière that Peel received a musket ball in the thigh. Never learning of his well-deserved Knighthood, he died at Cawnpore on 27 April.

In recognition of his services, Harvey was promoted to Leading Stoker on 22 February 1858. His Medal, with clasps 'Relief of Lucknow' and 'Lucknow', was sent to him on 9 November 1862.

Subject to 20% VAT on Buyer’s Premium. For more information please view Terms and Conditions for Buyers.

Sold for

£2,000

Starting price

£1200