Auction: 22001 - Orders, Decorations and Medals

Lot: 287

'Here I could hear men shouting out for help but because of the darkness I could not see them. Swimming aimlessly around in the icy cold water, I became aware that the ebb tide was carrying us all towards the sea. Soon I lost any idea of time and it seemed that I had been in the water for ages. Rapidly I was getting to the point that I did not care anymore. Shouting for help appeared to be useless, nobody could hear us. Ships had passed some distance away but they did not see me … '

Leading Seaman Fred Henley, one of the lucky few to be plucked - at length - from the icy waters of Thames estuary following the loss of H.M. Submarine Truculent in January 1950.

An emotive Second World War campaign group of four awarded to Ordnance Artificer E. C. 'Ed' Buckingham, Royal Navy

An experienced 32-year-old submariner by the post-war era, he was among the fortunate few to survive the loss of H.M.S. Truculent when she instantly capsized in the Thames estuary after a collision with the Swedish tanker Divina on the night 12 January 1950: he had been marking the occasion of his 32nd birthday with fellow shipmates when the Divina struck

As the stricken submarine hit the seabed at nine fathoms, just two compartments were brought under some semblance of control, from which - after a nerve-racking 45-minute delay to flood them in preparation for a Davis-apparatus escape - emerged some 57 men

According to a report in the The Times, the men formed an orderly queue as the water rose in their compartments, prior to exiting Truculent, so much so that one survivor likened the gathered throng to a typical London bus queue

Tragically, the calm and courageous actions of Truculent's ship's company were ill-rewarded, the majority succumbing to exposure in the icy waters of the Thames estuary

For film footage and interviews with the survivors, see:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X8qRRJjlYv4

1939-45 Star; Atlantic Star; War Medal 1939-45; Royal Navy L.S. & G.C., E.II.R., 2nd issue (MX. 88348 E. C. Buckingham, O.A. 1, H.M.S. Adamant), mounted as worn, together with a Submariners' International (British Section) metal and enamelled badge, very fine or better (5)

Edward Charles Buckingham was born at Toxteth Park, Liverpool on 12 January 1918 and was working there as a shipyard electrician on the eve of the outbreak of hostilities in September 1939. Of his subsequent wartime career in the Royal Navy, further research is required, but it is likely he witnessed active service in submarines.

Be that as it may, he was certainly serving in the submarine branch in the post-war era, for he was an Electrical Artificer 2nd Class in H.M.S. Truculent at the time of her loss on 12 January 1950.

Various accounts of the disaster are available online, and Buckingham is quoted in many of them. But for the purposes of this catalogue entry, a report published in The Times is quoted:

'Some details of what happened inside the Truculent after the collision yesterday were given by survivors after they were landed at Chatham this afternoon.

Tired, unshaven, tousle-haired, dressed in an odd assortment of warm service clothing, they sat around a table in the barracks and in a subdued, dazed, fashion told their story.

Apparently immediately after the collision the men were all went aft, and one man estimated that there were about 40 of them in the aft-chamber when the bulkhead doors were shut. "We got as many through as possible; it took about two and a half minutes, and then we had to shut the doors." Petty Officer Fry said that as far as he knew the rest of the ship was flooded. "We decided to try to escape." Only two compartments, he thought, the engine room and the stokers' mess deck, were not flooded; and "all the fellows who were in these two rooms got out."

The accident occurred at 7.05 p.m., and at about 7.40 p.m. the Davis escape tunnel was brought into use, and the controlled flooding of the engine-room began to even up the water inside and out.

At 8.10 p.m. everything was ready and Petty Officer Fry was the first man out. A number of men did not have Davis escape apparatus. Telegraphist Robert Almond said he was the third or fourth out and he had no apparatus as the ship was flooded so quickly that he did not have time to pick up a set. He took a deep breath, dived under the water and up the tunnel, hoping for the best. It took the men 30 to 40 seconds to get to the surface, but they said it seemed like hours.

Engine Room Artificer Frank Mossman said he was on watch in the engine room when the collision occurred. He seized a Davis apparatus. "We just waited for the lads to assemble, then we shut the bulkhead doors. Everything went very smoothly. We waited for the flooding up of the engine room and then just popped out one after the other without any trouble at all. We stood in a queue as though we were waiting for a bus. On the way up I had a clear mess-up with the jumping wire just clear of the hatch, and was caught in it for about a minute. It seemed an eternity." He was picked up in the darkness about an hour and a half after the collision.

Electrical Assistant Edward Buckingham said that the last man out was Chief Engine Room Artificer Hine: "I was last but one, but he told me to go on ahead. He got out, but as far as I know he has not been picked up."

Mrs. Hine, wife of Chief Engine Room Artificer Hine, was among those waiting for news at the dockyard. With her was her elder daughter, Doreen, aged 13. She said she had "been through all this before" as in 1942 the submarine in which her husband served had been sunk and she had waited for four months before hearing that he was a prisoner of war … '

Tragically, as it transpired, Hine was among those who lost their lives on the night of the 12 January 1950.

However, as cited, 'Ed' Buckingham was among the survivors, and he was subsequently called upon to give evidence in the Admiralty's Board of Enquiry; a copy of his evidence is included.

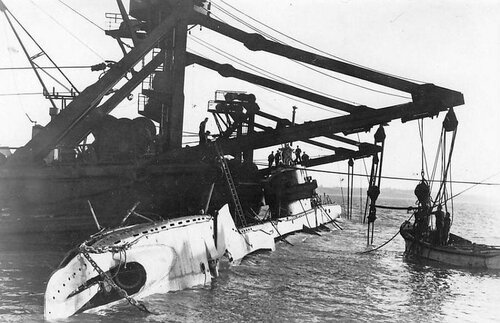

Truculent was salvaged on 14 March 1950 and beached at Cheney Spit. The wreck was then moved inshore, where 10 bodies were recovered. Subsequently re-floated and towed into Sheerness Dockyard, she was scrapped later in the same year.

Regional navigation rules thereafter mandated a 'Truculent Light' - a panoramic white light on the bow of submarines moving under their own power - thereby ensuring that they remained visible to other vessels.

Starkey remained in the submarine branch and was serving as an Ordnance Artificer in the depot ship Adamant at the time of his subsequent award of the L.S. & G.C. Medal.

He died in Hampshire in October 2005, aged 87 years.

Postscript

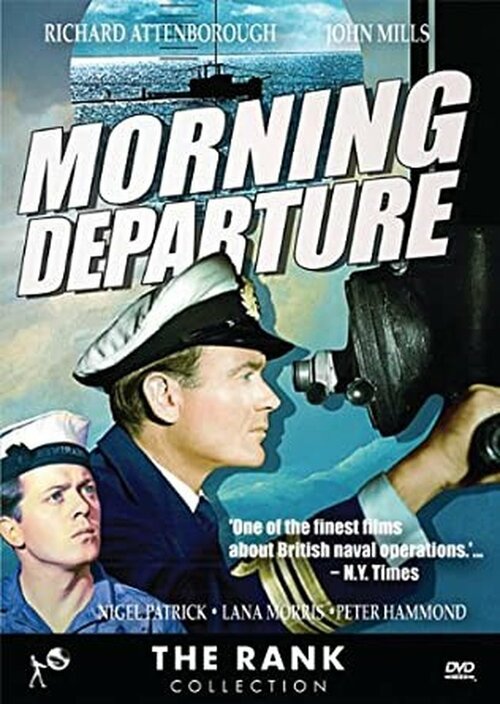

On 21 February 1950, the BAFTA-nominated film "Morning Departure" was released. Richard Attenborough and John Mills aside, a young Michael Caine appeared in the film, his first - uncredited - part, as a teaboy.

The story, of a British submarine on a training exercise that sinks to the seabed after encountering a mine, is told from the perspective of her trapped survivors. Filming finished shortly before the loss of the Truculent. However, after considerable debate, the decision was made to go ahead with the film's release, and to add the following statement in the opening credits:

'This film was completed before the tragic loss of H.M.S. Truculent, and earnest consideration has been given as to the desirability of presenting it so soon after this grievous disaster. The Producers have decided to offer the film in the spirit in which it was made, as a tribute to the officers and men of H.M. Submarines, and to the Royal Navy of which they form a part.'

Whether 'Ed' Buckingham chose to view it is not known.

Subject to 20% VAT on Buyer’s Premium. For more information please view Terms and Conditions for Buyers.

Sold for

£400

Starting price

£300