Auction: 21003 - Orders, Decorations and Medals

Lot: 2

The fascinating Military General Service Medal to the Spy, Soldier, Businessman, Travel Writer and Academic, Ensign S. Laing, Royal Staff Corps, 'The Scottish Scarlet Pimpernel', who saved three shipwrecked sailors from Napoleon's agents

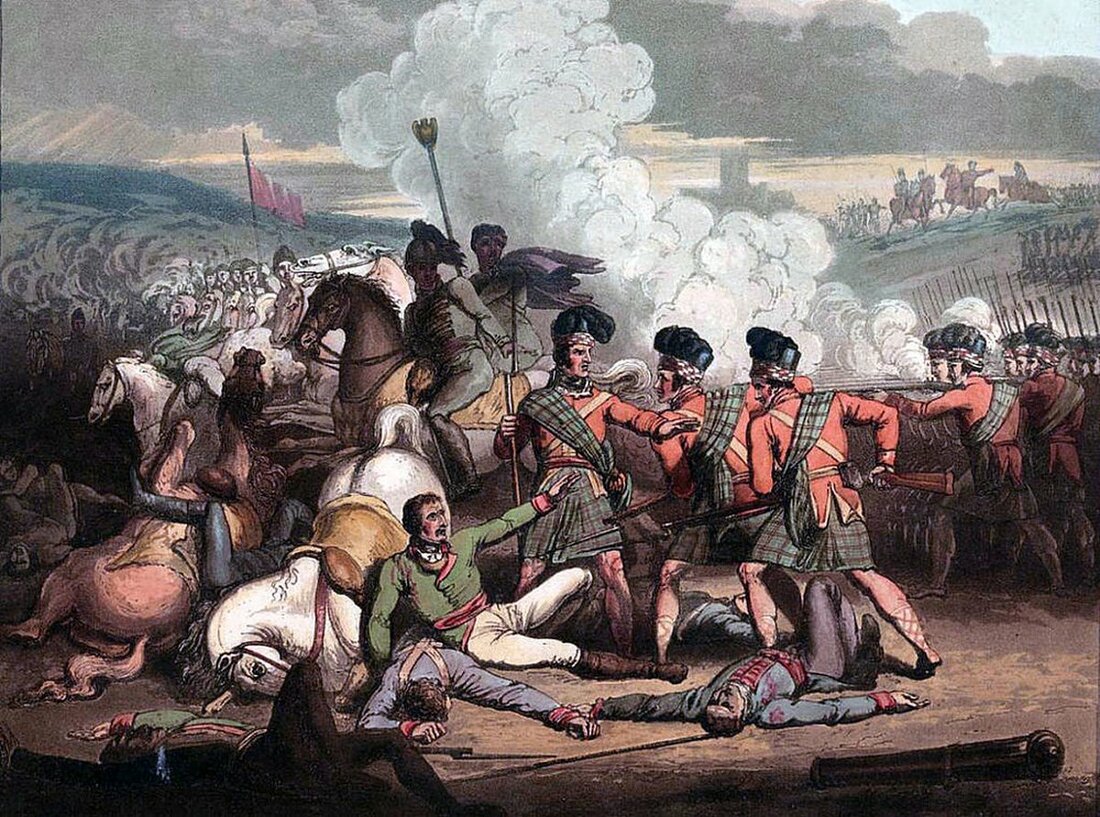

Marched under Wellington, and was present at Roleia and Vimeria, having his horse shot from under him at the latter and replacing it with that of a captured French General, he was later on the Staff of General Leith under Moore at Corunna and led the Grenadier Company of the 59th in a bayonet charge against French positions, other adventures including being almost murdered by Portuguese peasants who took him for a Frenchman

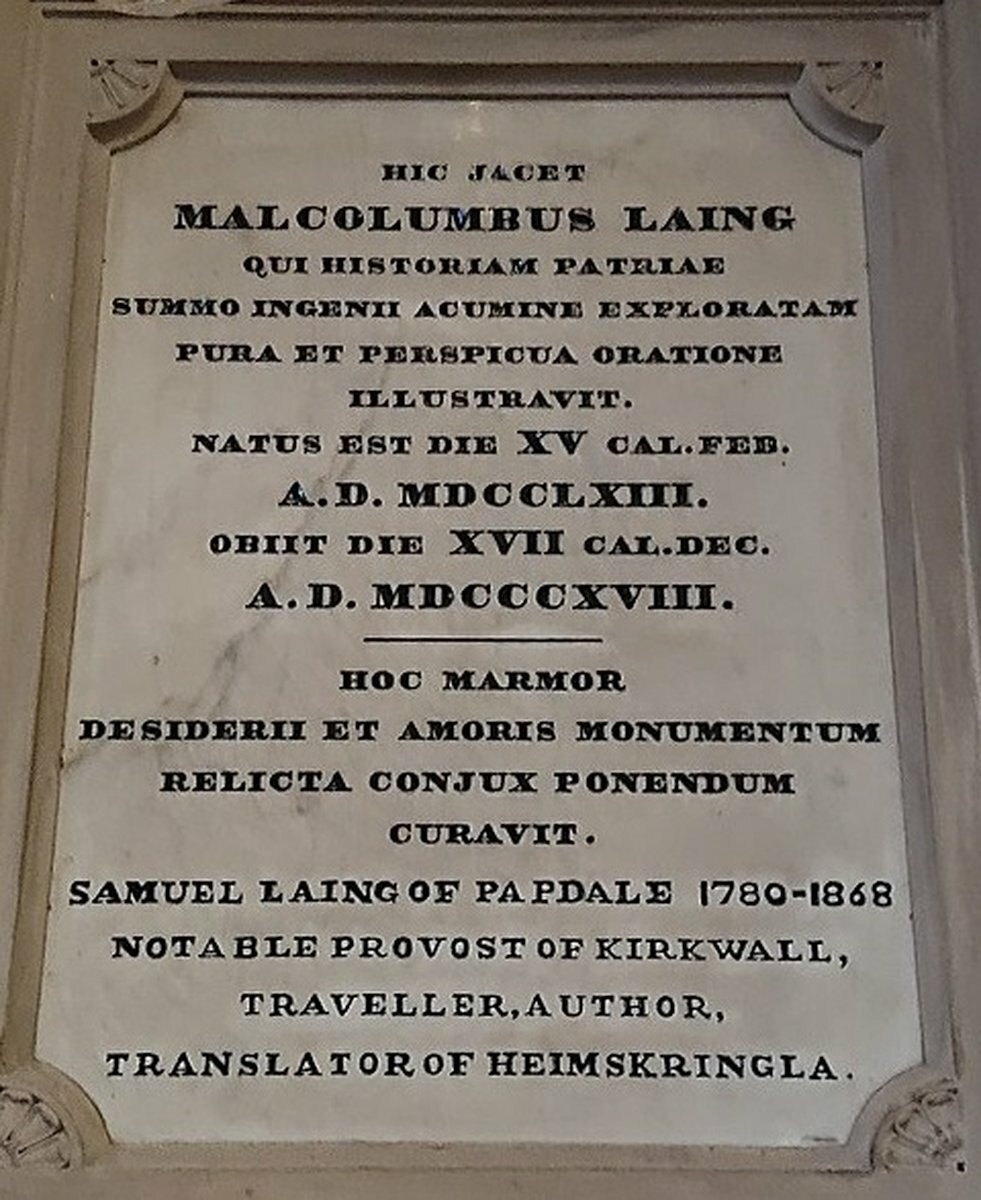

In later life he wrote the first English translation of the Norwegian Heimskringla and almost brought down the Swedish Government with his incendiary description of their corrupt political establishment

Military General Service 1793-1814, 3 clasps, Roleia, Vimiera, Corunna (Saml. Laing, Ensn. Royal Staff Corps), light contact marks, very fine

Provenance:

Sotheby's May 1910.

Glendining's September 1963 & March 1985.

Samuel Laing was born in 1780, the youngest son of Robert Laing, Provost of Kirkwall and Barbara Laing (née Blaw). He was the youngest of seven boys and two girls and as such was without inheritance, a fact to which he attributed his strangely eclectic career. Educated mainly at home he was briefly schooled by a minister in Kirkwall and from an early age showed an aptitude for academic matters. His family's intentions for his future were mercantile in nature with the expected inheritance of his brother Gilbert to provide the necessary financial backing. However, first he needed to learn the necessary skills. After a two year sojourn in Edinburgh with his eldest brother Malcolm, Laing was sent to the counting house of Mr Robert Gladstone (the uncle of future Prime Minister William Ewart Gladstone) to serve as a Clerk and learn the basics of business. Leaving Liverpool after a year he travelled first to Hamburg and later Kiel, continuing to busy himself with mercantile pursuits until he found himself in Holland. Here he stayed, in 1803, with the family of Mr Ferrier, a partner of the British Consul at Rotterdam. This was a difficult time as Holland was in effect controlled by the French and, while not legal, trade with England was allowed to continue as quietly as possible. At this time Laing fell for Mr Ferrier's daughter and narrowly escaped what he later called an 'imprudent marriage'. His infatuation notwithstanding, it is at this time that his wild side became apparent.

The Scottish Scarlet Pimpernel

In response to the fears of French invasion, the Dutch-built Schuit, Experiment left Yarmouth on 17 November 1803. Her mission was to spy out concentrations of French troops and ships on the Dutch coast. The small vessel with her crew (consisting of just a Lieutenant, Acting Lieutenant, Midshipman and eleven sailors) was ideally suited to the task. What she was not suited for, however, was the rough winds which blew up from the north-west catching the ship between deep seas, in which she was sure to founder, and the hostile coast. Taking the lesser of two evils Lieutenant Hanchett ran the vessel aground on a sandbank south west of Goeree. Finding themselves unable to free the vessel when the weather cleared they were forced to burn her. Quickly captured, they were taken to Zierikzee and there after 17 days the three officers managed to escape. Still in uniform with only their greatcoats to hide their allegiance they managed to contact Mr Ferrier. Given that they had escaped from custody they would very likely have been executed if they were retaken so their predicament was indeed a serious one. On hearing of the officer's distress, Laing immediately volunteered his services to help them escape. Knowing that a party of four would be too large to escape he placed the Acting Lieutenant, W.C.C. Dalyell, aged 19 and Midshipman Bourne, aged 16, in a boarding school with instructions that they 'be cautious and act boyish in their conduct'.

With those two secure, Laing and Hanchett dressed in plain clothes, set off by night on a barge headed for Amsterdam; from there they travelled by boat to Memdeblik and from there, to Groningen. The boat journeys were particularly hazardous as their close proximity to the passengers would have soon made their nationality clear. To get around this both immediately went to bed as soon as they were aboard. The drinking and talking of the other passengers made this difficult, doubly so when the conversation turned to the recent escape of the three British officers. Arriving at Groningen at night they were able to bed down in an alehouse outside the town. This was fortunate as if they had arrived during the day they would have needed to explain their presence to the town Commandant. When morning broke Laing and Hanchett were to be found fleeing across country before the town awoke. Passing the Prussian frontier and trudging their way painfully across muddy ploughed fields (avoiding the roads lest they encounter French or Dutch troops who patrolled in search of deserters) they finally reached Embden.

Hanchett took ship from there aboard an American vessel. Three days out of port it too was wrecked. In spite of this he succeeded in returning to the Squadron of Sir Sydney Smith and from there to England. Writing from there he was able to arrange for his two subordinates to travel home by the same route as him under the guise of visiting a certain 'American relation' in Embden. Hanchett is an interesting character in his own right, reaching the rank of Post Captain in 1809. He lost a leg in the attack on Flushing that year and commanded a Squadron to supress smuggling off Kent. He was later dismissed after an accusation of taking bribes from the smugglers. Laing, meanwhile, had decided to leave as soon as possible. The morning after Hanchett boarded his ship he set off back towards Rotterdam. The weather had become freezing cold and so Laing was able to skate on the rivers and canals to speed his progress. This had the added benefit of keeping him away from the Franco-Dutch patrols although on one occasion, in the middle of a snow storm, he was challenged by a sentry on the walls of the fortified town of Nieweschans. Fortunately for Laing, while the keen-eyed sentry had spotted him through the snow and was able to challenge him he was unable to shoot at or pursue him. So Laing simply skated on past the town. He made it back to Rotterdam in time to wish the other two officers well of their journey home and presumably to pass on his good wishes to their 'American relative'.

England and the Army

With Laing back in Rotterdam he was again under the protection of Mr Ferrier. However with plans to invade England ramping up, the French, in response to what they saw as the slow progress of the Dutch preparations in this matter, were seizing control of their ports. It was clear to Laing that if he were suspected of helping the British officers to escape he would be arrested as a spy. Indeed this was increasingly likely as the French-controlled ports were increasingly tightly controlled by police and government agents. In order to escape the port without falling afoul of this network, in January 1804, Laing was forced to pose as a German sailor, escaping aboard a German ship and landing at Gravesend, Kent. It is symptomatic of the invasion fears then running rampant in Britain that even the arrival of a 24-year-old clerk from Rotterdam caused enough of a stir that an agent of the Secretary of State was sent to interrogate him on the state of the Franco-Dutch preparations. Despite his dramatic adventures on the continent Laing was without employment and, still unable to rely on his family, decided that his best option was the Army. Given his background working on the continent, good education and language skills he decided that the Royal Staff Corps would best suit him. This formation was founded circa 1800 with the intention of circumventing the ineffective Board of Ordnance to which the Royal Engineers answered. Their role was essentially that of an engineering staff officer; they were involved in planning and logistics but also responsible for surveying and impromptu or short-term construction projects - Laing's skills made him an excellent candidate. After eight months he was finally offered a commission as Ensign without purchase with the Royal Staff Corps, which he accepted on 26 September 1805. Upon joining the Corps in their quarters at Hythe, Laing began work with them on the excavation of a canal in Romney Marsh, Kent, intended as a military defence of the roads between the Kent coast and the interior. During this time he became acquainted with two officers in particular; a Lieutenant Willermin, an older soldier in his forties and of Swiss extraction, and a Captain Charles Napier, later famous for his conquest of Sindh and replacing Lord Gough as Commander-in-Chief, India.

After a brief spell at Horse Guards, drawing up plans for the Peninsula campaign, Laing's Company, under Captain Colleton, was ordered to Portsmouth where they embarked for Gibraltar aboard the transport ship Harpooner. The force, made up of 6,000 men under Sir Brent Spencer, had no real target in mind but was intended as a reinforcement should it be needed in the area. At Gibraltar, Laing was able to indulge his academic side again, burying himself in the Library created by William Pitt in 1805. While here he also observed from the walls the engagement fought between the French and Spanish navies which resulted in the surrender of the French, caught at anchor between the Spanish ships and the shore.

Portugal 1808

Laing's Company joined the British Army in Portugal under Sir Arthur Wellesley, landing at Figueria. Making his way to join the army Laing discovered that General Ferguson was commanding a body of troops nearby and made his way to the General's Headquarters. Ferguson was a friend of his brothers Gilbert and John - the latter having joined the army himself and served as a Brigade Major on Ferguson's staff in the conquest of the Cape of Good Hope. Having this personal acquaintance with the General Laing manged to to attach himself to his Staff and as such serve with an unspecified, roaming, commission. That is not to suggest that he was idle, as he states in his Autobiography:

'It is not easy to give an idea of the cheerful, exhilarating life of a soldier in the field. Every hour has its novelty and its occupation. One has the same joyous feeling as at a fox chase.'

It was with such that he arrived at Rolica on 17 August 1808 to take part in the first battle the British Army fought on the Peninsular. During the fighting Colonel Bradford, an officer of Laing's acquaintance, was killed and he was presented with his watch by one of the Colonel's soldiers. Recognising it, Laing in turn presented the watch to General Spencer whom he believed to be a relation of Bradford (indeed he was serving at the time as the General's ADC).

'The old General showed a great deal of feeling, although we were then within pistol shot of the enemy. This General Spencer was not a very clever man, but he was certainly goodhearted and brave. The weather was hot, and the road dusty and close from the smoke of the gunpowder and, having my pocket full of apples, I was munching one now and then to moisten my throat. I observed the old General eye my apple although he was then in the advance of the men pushing up the road and the enemy retiring step by step and keeping up a sure fire at a short distance from us. I presented him with an apple, and his coolness in sitting on his horse eating his apple in front of the men, and within a few paces of the enemy, seemed to inspire the advance with the same steadiness and coolness. There was no sense or feeling of danger there. It was one joyous burst of animated activity' IBID

Sadly this is the only anecdote that he provides of his role in the fighting but his proximity to the frontline and his observations of conduct, such as soldiers often firing high when overcome with excitement, speak to a genuine experience of battle. With the victory at Rolica and receiving reinforcements, the British advanced several days later on 21 August 1808 to Vimeiro where the most important engagement of the campaign took place. Here, again, General Ferguson's Brigade was heavily engaged and Laing almost suffered a premature end to his adventures:

'In this battle I lost my lately purchased Portuguese horse. A musket ball passed between my stirrup leather and my leg to his heart. I felt him shiver underneath me, and had just time to get off when he dropped dead. I borrowed a horse, a little white one, which one of our soldiers had caught as it was galloping about without a rider, as many others were, and I rode it for the rest of the day. It was the horse of General Brunnier [SIC], a French Officer, who had been thrown off and taken prisoner. After the battle I restored it to the soldier who had first caught it.' IBID

He ventured back to the site of the battle the next day in order to satisfy himself of the assertion that had General Hill's Brigade been allowed to advance as ordered by General Wellesley, and not been countermanded by General Burrard, the French may not have been able to escape. He concluded that this was the case but placed the blame on the Government for sending Burrard so hard on the heels of Wellesley that he arrived mid-campaign and unaware of the situation. Billeted at the home of the Marquis de Minas for several days before General Ferguson left for England, Laing was then employed along with the now Captain Willermin and Captain Pierpoint to make a map of the country they had just passed over. Though only conjecture, he believed this was intended to prove whether or not it would indeed have been practical to cut off the French withdrawal from Vimeiro. At this stage the Convention of Sintra had been signed over the protests of General Wellesley and, while Portugal was now secured, the commanders of the Army were riven by internal divisions.

Capture

The three Officers moved out over the area they were to survey, separating in the mornings and meeting back up to join their work together at breakfast each day. At Rolica they stayed for several days at the house of one Don Miguel who entertained them and gave them 'the only tolerable wine we tasted in Portugal.' Separating upon leaving Don Miguel's home they agreed to meet a day or two later at a nearby town, Laing rode to the town of Cadaval and was entertained there by a Portuguese officer before deciding to climb a nearby mountain, Monte Junto. Unfortunately, his cavalier attitude finally got him into significant trouble:

'The guide was probably forced into the service, and did not expect any recompense and, finding that I went on and paid no regard to his signs to turn into any of the wine houses we passed on the road he got very sulky. I was occupied in sketching and taking notes and, after reaching a small village at the foot of the mountain, my guide in spite of me walked into a house and left me.

I cared little about him as the country was open and pushed through the village and began to ascend the hill. I had scarcely got the breadth of a field or two out of the village, before I found the whole population at my heels. They soon came up with me as I was at a loss to know what they wanted. They seized my sword, my spyglass which they mistook for pistols, and marched me back as a prisoner. The fellow who had been my guide drew his knife, a formidable one, two or three times, but whether as a bravado or with any ill intention I know not. [...] We passed a kind of gaol in the village and they discussed about shutting me up till morning. If they had I am certain I should never have got out alive in the temper in which the villagers were. As well I could understand they took me for a French spy, who had got into the clothing of an English officer. They had no idea that the British could be reconnoitring [...] the country so far behind the enemy. They determined very fortunately for me on carrying me at once to Cadaval, and delivering me up to the Commandant, the officer with whom I breakfasted.'IBID

Laing was fortunate that the Commandant, despite not releasing him, did provide him with a proper meal and have him escorted to British lines. Nevertheless he acknowledged 'I am not sure that I ever was in more imminent peril'. Given the catalogue of adventures his life had thus far formed, this is a rather astonishing statement.

The Retreat to Corunna

With the completion of the survey Laing purchased a new horse to replace the one killed at Vimerio, which was from a stud of Sir Hugh Dalrymple, one of the Army commanders and the man behind the Convention of Sintra. After General Ferguson's return to Britain, Laing was again serving with the Royal Staff Corps under the command of Sir John Moore. Laing did not rate the new General highly, considering his arrangements for the campaign into Spain to be poor. Though he acknowledged that this may have been due to Moore's orders to consult with the British Envoy to Madrid, Mr Frere, who frustrated his attempts to organise matters properly. However he lays the chief failure of the campaign at Moore's door, namely the decision to march with the artillery on the left bank of the Tagus River, this made it impossible to link up with Sir David Baird's troops at Corunna for fear of being cut off from the Artillery and its cavalry escort over the river. During the march from Portugal Laing suffered another upset with the locals, trusting again to a guide to lead him and a small train of waggons to Ciudad Rodrigo; the column was abandoned at night in rough country. Floundering through the unfamiliar terrain for some time they finally came to a walled enclosure where they were able to spend the night in some comfort before continuing to Ciudad Rodrigo. Passing through Salamanca, where Laing briefly fell ill with some form of dysentery, they came to Sahagun where he was sent with a Major de Blaquiere, son of Lord de Blaquiere, to reconnoitre the River Esla and as a result was not present at the engagement at Sahagun between the British and French cavalry. He was however present for the skirmish at Lugo on 7 January 1809. In this engagement the Brigade-Major of General Leith had his hand shot away and Laing was appointed in his place, serving on the General's staff until the army returned to England.

From Lugo the army marched towards Betanzos and from thence to Corunna. This was the famous 'Retreat to Corunna'. Laing's Brigade marched from Lugo with 1,200 men of the 59th, 72nd and 64th Regiments. When they reached Corunna they had less than twenty men present from each Regiment - the rest were strung out on the road through the mountains. Laing himself survived the journey in good shape, as he says himself:

'As for myself personally my good horse made me as comfortable as possible. On the second night we were both exhausted and I awoke on his back standing by the ditch on the side of the road. We had both been asleep for some time as our Brigade was some way ahead. I had used the precaution to stuff my saddle portmanteau with as much corn as it would take, instead of carrying my useless baggage, and my horse was comparatively fresh on our arrival at Betanzos.' IBID

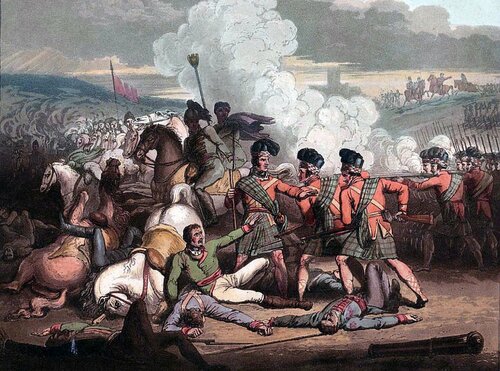

Arrival into Corunna brought relief from the elements and rest after the intense forced march - however the transport ships intended to rescue the army had not yet arrived and it soon became clear that a battle was inevitable. Laing himself saw little of the battle, being stationed in the second line. Under orders from General Leith, the Brigade lay flat upon the ground. They soon came under heavy fire from a hedged bank not far from their position from which the enemy could pick them off at will and without any effective reply. Leith ordered Laing to take the Grenadiers of the 59th and clear this hedge at bayonet point. During this engagement Laing related a strange episode:

'A remarkable circumstance of blind animal impulse struck me in the course of this advance. When we got over the bank into the field we found a Lieutenant Nunn, at a kind of gap which his Regiment had attempted, dying on the ground of his wounds. He belonged to one of the Regiments, the 82nd I believe, which we had replaced. One of the Sergeants of our party of the 59th, either crazy with terror or mad, after we had recognised the dying man who had on his uniform, deliberately took up a musket and was on the point running him through with the bayonet. The fellow was not drunk and saw by the uniform it was a British officer; and it was very unlikely he could have had any personal malice against a dying or rather dead officer of another Regiment. I can only ascribe the man's blind impulse to bayonet the body to the indescribable lust for blood into which the more animal soldiers like the hyena falls when he has acquired a taste for it.'IBID

With the battle over the British left Spain, Laing going aboard the warship Bulwark with Leith and his ADC. However it was to be the end of his military career: during the retreat he had heard that his brother had finally inherited the mining business and a role awaited him there which would provide an income of £800 a year. Since he was by this stage engaged to be married and still only an Ensign in rank, despite being 29 years old, Laing decided that he had joined the Army too late and his only hope of maintaining a family would be in taking on the mining role.

Life after the Army

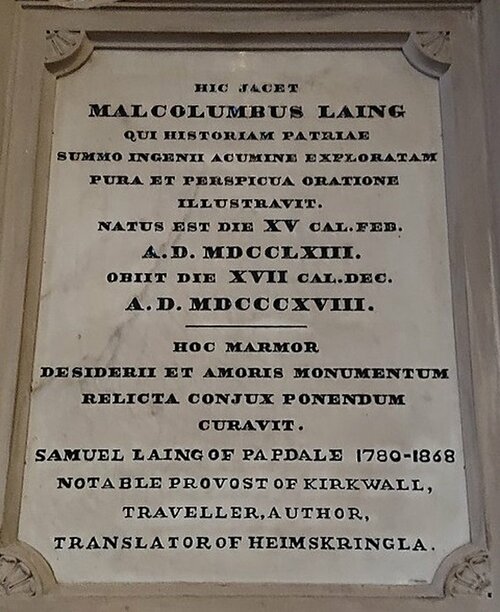

Laing did not take well to business at first. The establishment of a herring fishery in 1816, which developed into the village of Whithall, Stronsay, and eventually proved to be a financially sound move - however for a time he was in dire straits. It was whilst contemplating the prospect of needing to emigrate to America in search of work that he received word of the death of his brother Malcolm, which passed the largest part of the Laing fortune onto him. He became Provost of Kirkwall and moved into the family house at Papdale. This short reprieve was ended with the collapse of the Kelp market on which his business relied and Laing turned to scholarship to make a living, working as a travel writer. Touring Norway he made a Journal of Residence from 1834-36 describing the country, its people and Government. In this he formed a favourable opinion of Norway - one not echoed when he visited Sweden in 1839, which he described as being run through an antiquated class system which favoured only a privileged few from behind a false democracy. Indeed his book on Sweden was so critical of their Government that a commission was created to look into the issues he raised, much to the delight of the people and Government of Norway. His greatest scholarly achievement however was doubtless the translation of the Heimskringla, the Saga of the Norwegian Kings. Laing died at 4 Lynedoch Place, Edinburgh, on 23 April 1868, and was buried at Dean cemetery. His son, also named Samuel Laing (1801-97), went on to become Managing Director of the London, Brighton and South Coast Railway and stood as an M.P. for Wick in 1852 and 1859, later being appointed Finance Minister for India; sold together with a copy of The Autobiography of Samuel Laing of Papdale, copied extracts from the book, auction listings from Glendining & Co 1985, several pages from ONFA News, the Tour Scotland website and a 2001 article from the Nessie's Loch Ness Times.

Subject to 20% VAT on Buyer’s Premium. For more information please view Terms and Conditions for Buyers.

Sold for

£6,000

Starting price

£2800