Auction: 21002 - Orders, Decorations and Medals

Lot: 165

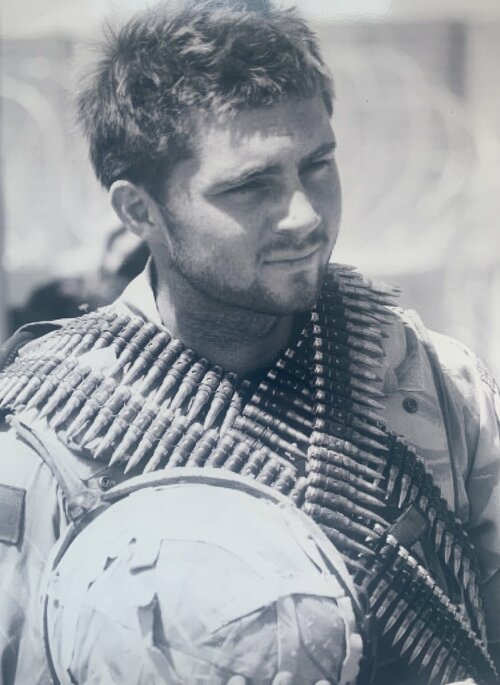

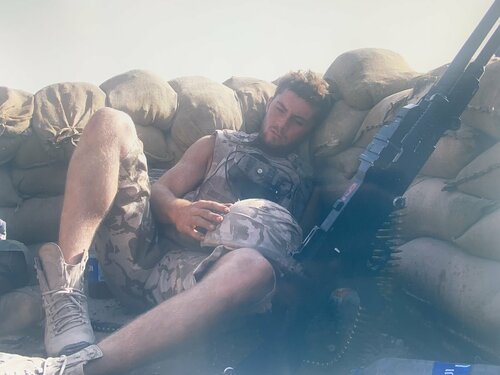

(x) A poignant Afghanistan 2008 M.I.D. group of four awarded to Lance-Corporal J. J. Mizon, Queen's Company, Grenadier Guards, who was featured in both BBC television documentaries Taking on the Taliban and latterly in the moving Jack: a soldier's story with Ben Anderson which featured his stuggles in re-adjusting to life off the battlefield

N.A.T.O. Medal 1994, 1 clasp, Non-Article 5; European Security and Defence Policy Service Medal 2004, 1 clasp, Althea; Iraq 2003-11, no clasp (25152886 Gdsm J J Mizon Gren Gds); Operational Service Medal 2000, for Afghanistan, 1 clasp, Afghanistan, with M.I.D. oak leaf (25152886 LCpl J J Mizon Gren Gds), mounted court-style as worn, pin removed, good very fine (4)

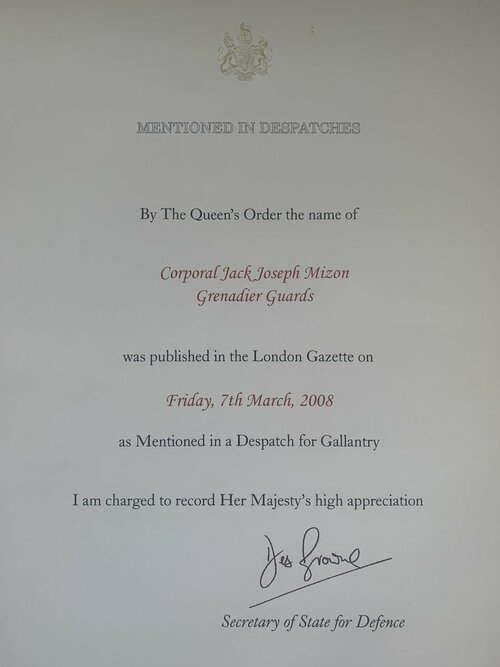

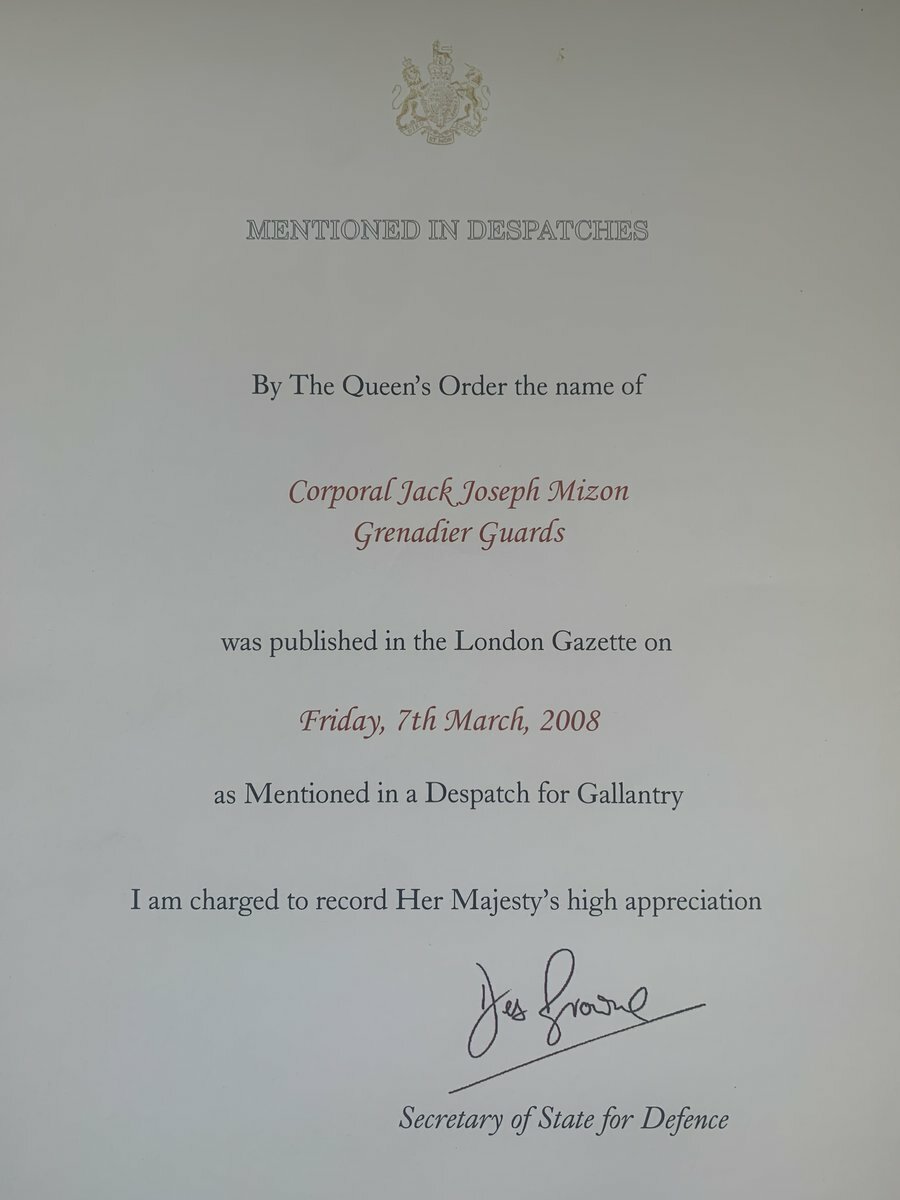

M.I.D. London Gazette 7 March 2008. The Grenadier Guards website at the time gave the following:

'Mizon repeatedly demonstrated exemplary, level headed courage. His coolness under fire and disregard for his own safety in the face of extreme adversity undoubtedly saved both Afghan and British lives.'

Jack Joseph Mizon, a native of Tottenham, joined the Grenadier Guards in September 2002. It was on his fateful tour of Afghanistan with the Queen's Company, that Mizon first crossed paths with Ben Anderson, the British journalist, television reporter, and writer. At that time he was featured in the BBC production Taking on the Taliban, which followed his unit through the heat of their tour. Having returned home, Mizon soon found himself struggling to adapt to life, like so many of his comrades, finding himself unable to control his emotions at times. This led to his assault of a Police Officer which forced him to flee the United Kingdom for a time, but he returned to face the music and re-kindled his relationship with Anderson, who thence set out to produce Jack: a soldier's story. Anderson wrote for the BBC:

'Jack Mizon, a 23-year-old from Tottenham, was a Lance Corporal with the Queen's Company, the Grenadier Guards, and last year served for six months in Helmand, Afghanistan's violent province.

I spent two months in Helmand during that tour, and by the end, two of the unit's 36 men were dead, and 15 seriously injured. Jack, while physically unharmed, was a changed man. After the first battle, which had gone very well, he seemed to love life as a soldier. "It was fun," he said, still out of breath. "Everyone's alive. Sweating, but alive. Next time will be good."

But within a month, the talk had changed drastically.

Jack was out on a patrol when an IED (improvised explosive device) was detonated just metres from him, badly wounding one of his friends.

A week later he was in a convoy hit by a suicide bomber. The driver was killed and all of Jack's other comrades were seriously injured - he was the only one that walked away unscathed.

This was just before an eight-hour battle, which led to several days of constant fighting to clear the town of Adin Zai. Visibly exhausted and shaken, he said: "I expected it to be bad, but this last two weeks has been really bad. I want to go home."

Readjusting to the often mundane life back on barracks was always going to be difficult after that. One of his best friends, Guardsman Ryan Lloyd, could see that Jack found it difficult.

"The first few weeks it was a struggle for him, definitely. You've gone from having all the responsibility in the world over there - people's lives depend on it - and then you come back and you're just a name and number again. It's hard to get your head round it."

Jack was sent to one trauma management session. He says he told the psychiatrist that he was having anger problems, seething with rage in an empty room for no reason. "I felt like I was going to explode all the time, I couldn't even speak to people."

He says he was told he was fine, and everything he was experiencing was normal, but after some pushing Jack was granted another session. But due to the army psychiatrist being on holiday and other complications, he would have to wait six weeks.

It was during this time that Jack got into trouble. Not long after getting a special commendation for bravery, he got into two fights, one involving a police officer, and immediately went awol, fleeing Britain for Canada. He gave himself up a few weeks later.

At his court case, the judge said that Jack's actions - assaulting a police officer and beating up an Aldershot man who challenged him - were unforgivable. His family, friends and commanding officers were convinced he was going to prison for at least three years. But he was spared jail thanks to the testimonies of his bravery, and given one last chance.

Jack's captain, Major Martin David, who is about to receive a military cross for his actions in Afghanistan, puts Jack's problems down to "ill discipline and alcohol". When he took charge of Jack's regiment, he was told the lance corporal was the worst "drama merchant who would bring him nothing but trouble". Before Afghanistan, Jack had two previous convictions for violence.

Jack's friend, Guardsman Lloyd, says he is not surprised when soldiers like Jack resort to violence.

"For the last eight months, all you've been told to do and taught to is fight and kill. Let's make no bones about it, our job over there, we go out and people die, whether it be us or the enemy. And you get back to the UK and there's going to be things that spill over, blatantly, especially when the beer is flowing. You can't just forget about what we've been through."

A senior soldier who knew Jack well says, off the record, "we train these men to never back down from any confrontation, no matter what the odds".

But even if Jack hadn't got into those two fights, it could still seem clear that, he, like many others, would have been traumatised by his battlefield experiences.

Many experts who deal with troubled soldiers argue that it's imperative they be given counselling even if they don't seek it. They say it takes a soldier with psychological problems an average of 10 years to admit they need help, by which time they have often gone through a serious problem like drug addiction, alcoholism, depression or divorce.

The Ministry of Defence says it has robust systems in place to treat and prevent stress disorders. "Counselling is available to service personnel and troops receive pre- and post-deployment briefings to help recognise the signs of stress disorder," said a spokesman, adding that decompression periods follow a tour of duty so that "personnel can unwind mentally and physically and talk to colleagues about their experiences in theatre".

But soldiers complain that these "decompression periods" are woefully inadequate. One soldier described his Cyprus decompression as "24 hours for us to get drunk and beat each other up".

The MoD also insists that medical discharge from the armed forces because of psychological illness is low.

"Out of around 180,000 regular service personnel only about 150 - or less than 0.1% - are discharged annually for mental health reasons, whatever the cause. Of the less than 0.1%, around 20-25 each year meet the criteria to be diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder."

This doesn't tally at all with what I saw in Afghanistan.

If my experience is at all typical, then I would put the number suffering PTSD much higher. Jack's case perhaps illustrates that if a soldier shows any signs of PTSD, or has had experiences that might contribute towards it, he should be forced to get help, or at the very last be properly evaluated.

The dangers are clear. More soldiers from the Falklands war committed suicide than were killed by the enemy. Over 1,000 of the UK's homeless are ex-forces.'

Mizon's story aired and has since passed into the public knowledge of how important the treatment for PTSD is for the wellbeing of our servicemen and women. He left the British Army in November 2008.

Sold together with original M.I.D. certificate, copied Certificate of Service, VHS and DVD copies of the documentaries, Grenadier Gazette (2007 & 2008), Guards Magazine 2009, besides a quantity of photographs and related material.

Further references worthy of viewing:

https://www.dailymotion.com/video/x7oysc

https://vimeo.com/17274101

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4lIi0dZVdyE

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rtC1hVA7pXE

Subject to 5% tax on Hammer Price in addition to 20% VAT on Buyer’s Premium.

Sold for

£3,200

Starting price

£1100